January 9, 2026

Air Date: January 9, 2026

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Environment and Rule of Law Under Trump

View the page for this story

In its first year, the second Trump Administration slashed environmental regulations and programs, overstepping its executive authority in the eyes of some environmental advocates. Pat Parenteau, who served as EPA regional counsel under President Reagan, talks with Host Aynsley O’Neill about the inability or reluctance of the judicial and legislative branches to provide a check on what he sees is abusive executive power that is threatening the health of people and planet. (14:12)

Innovation to Fund Tropical Forest Protection

/ Paloma Beltran & Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

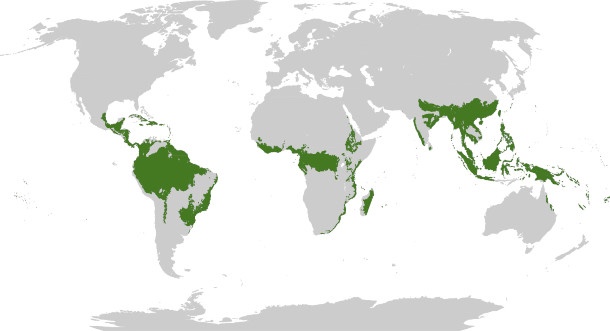

The new Tropical Forest Forever Facility launched by Brazil at the 2025 UN climate talks is different from other efforts to protect nature in that it doesn’t rely on charity. Instead, it’s an investment fund that will pay dividends to both private investors and governments that keep their tropical and subtropical forest intact. Host Paloma Beltran walks Host Aynsley O’Neill through how it would work. (09:00)

Sea of Grass and the Disappearing Prairie

View the page for this story

The American prairie is one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world, with numbers of species rivaling even a tropical rainforest. But today, just one percent of eastern tallgrass prairie remains, and western shortgrass prairie is disappearing at a rate of more than a million acres a year. Author Josephine Marcotty joins Host Paloma Beltran to discuss her book Sea of Grass: The Conquest, Ruin, and Redemption of Nature on the American Prairie. (17:01)

An Indigenous Bison Harvest

View the page for this story

Efforts to bring back bison are helping to revive Indigenous culture on lands across the US West. And as Colorado Public Radio’s Sam Brasch reports, this revival is taking place right in the city of Denver. (05:01)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

260109 Transcript

HOSTS: Aynsley O’Neill and Paloma Beltran

GUESTS: Chip Barber, Juan Carlos Jintiach, Josephine Marcotty, Pat Parenteau

REPORTERS: Sam Brasch

[THEME]

BELTRAN: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

BELTRAN: I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Taking stock of year one of the Trump administration assault on climate, environment and clean energy.

PARENTEAU: You can go across the country. They’re stopping solar development on public land. They’re stopping offshore wind on the Gulf coast, they’re opening up the Alaska wildlife refuge to oil and gas development for the first time in 50 years – etcetera.

BELTRAN: Also, the “sea of grass” that’s threatened by industrial farming.

MARCOTTY: So the paradox of the prairie is partly rooted in the fear that early colonialists had when they first encountered it. At first, they thought nothing would grow there because there were no forests, and they thought, well, there must be just bad soil. But it turned out to be the most productive soil in the world.

BELTRAN: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Environment and Rule of Law Under Trump

During his second term President Trump rescinded past environmental justice orders, stopped Inflation Reduction Act grants and eliminated EPA's environmental justice arm, leading to lawsuits from environmental groups and states. Pictured above is the W.A. Parish coal and gas generating plant in Texas. Frontline communities face disproportionate exposure to toxic smoke and other air pollutants due to systemic environmental injustices. (RM VM, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 4.0)

BELTRAN: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

It's been approximately a year since President Trump took office for a second time, and environmental protection has once again been on the chopping block. During the past year, federal agencies cut or reduced environmental justice programs and funding across the board. The EPA, an agency tasked with protecting human health and the environment, relaxed limits on air and water pollution. It also proposed scrapping a mandatory program in which power plants, refineries, and oil and gas suppliers report their greenhouse gas pollution. And in recent days the Trump Administration said the US would withdraw from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and no longer abide by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change treaty, which was ratified by the Senate in 1993.* But the reality of the climate crisis is here. And 2025 was also a year of record-setting heat and catastrophic storms. Pat Parenteau served as EPA regional counsel under President Ronald Reagan and he’s currently an emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School. He often joins us to analyze active environmental legal challenges across the US. But he’s here now to share his grave concerns about the direction of US environmental policy under President Trump’s second term.

PARENTEAU: The big difference between Trump one and Trump two is that the courts were able to stop Trump in his first term 90% of the time. In this term, the Trump administration has been much more successful in blocking efforts to challenge them in court. That's primarily because of the Supreme Court, with its ultra conservative, six member majority that steps into these cases even before they've reached the merits, even before there's been briefing and argument and facts and evidence, the Supreme Court has shown an inclination to step in and stop environmental rules in their tracks. That's a big difference. The lower courts are struggling to hold the line, hold the government accountable to the rule of law. This administration has no regard whatsoever for the rule of law. In fact, the courts are struggling with whether they can hold the Trump administration in contempt when the Department of Justice has, according to a New York University study, lied to the courts over and over and over again, misrepresented what the administration is doing, falsified declarations that are filed in court. It's amazing the outlaw behavior of an administration. And the courts do have the power to issue contempt citations, but the problem is the Department of Justice has to enforce contempt citations, and we know that under Pam Bondi, the Department of Justice will never enforce contempt citations against the Trump administration. So we're in a terrible pickle, if you want to call it that, but we are really in an unprecedented situation where the institutions of government, the checks and balances of government are not working. And of course, the environment is suffering, but many other parts of our society are suffering as well.

Under President Trump EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin has pushed to reduce or eliminate environmental protections. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 2.0)

O'NEILL: So in this current landscape in the United States, what would it take in order to get back this rule of law?

PARENTEAU: Well, that's a very interesting question, one we've never faced, at least to the scale that we're dealing with. And the United States has dealt with many crises over its period. I mean, you start with the Revolution, the Civil War, Civil Rights Movement, the anti-war movement. We've seen all kinds of political challenges. We've never seen an administration bent on violating the law, determined not to follow the law, determined not to follow the Constitution, daring the courts to stop them. And I don't know when or if the courts are going to be capable of stopping this administration. We've seen victories in the lower courts, in the trial courts, the district, the federal district courts, but what happens is they get appealed. And if they don't get appealed immediately to the Supreme Court, they get appealed to the intermediate Courts of Appeal, where there are hundreds of Trump appointees on the bench. Sometimes you draw a panel in the circuit courts where there are two Trump appointees on the bench, and guess what happens? If a lower court has stopped the administration, it gets to the Court of Appeals and two Trump appointees vote to stay the lower court's orders. That's what happens. So lawyers are scratching their heads about, "what do we do in this situation?" You could turn to Congress, right? You could have Congress impeach members of the administration — and there are several that I could nominate, right? — but Congress isn't going to do that. Congress is in the grip of President Trump's political power right now. We've seen that. It's incapable of correcting and challenging and dealing with what the Trump administration is doing. So I'm not sure where this goes. It's clear that unless and until we get different people elected to national governments and state governments, and that's a long process, I grant you, and it's not a legal question, it's a political question, but unless and until we do that, I'm not sure we can rely on the courts to save us.

Scientists with the EPA’s Office of Research and Development were charged with conducting independent research. One such area of study would have the goal of ensuring that emissions from factories don’t endanger neighboring communities. (Photo: André Robillard, Unsplash, public domain)

O'NEILL: Now, in the past, we've talked about how the Trump administration went after the endangerment finding. This is the finding authorized by the Supreme Court and by former President Obama's EPA that determined that climate heating endangers health. Where does that legal challenge stand?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, we were promised by administrator Zeldin a repeal of the endangerment finding in December, but because of the government shutdown and some other things, they've had to postpone that. But we're expecting any day now, literally, that Zeldin will issue a final decision repealing the endangerment finding, which undergirds all of the climate regulation. It undergirds the power plant rule, the methane rule, the tailpipe rule that regulates emissions from automobiles and trucks and so forth. So we're now expecting to see the repeal of the endangerment finding this month. That will trigger judicial review in the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, which still has a balanced representation of judges appointed by bipartisan administrations, in other words, Democrats and Republicans. So there's a very good chance that the repeal of the endangerment finding will be overturned by the DC Circuit, but it will then go to the United States Supreme Court, where all bets are off. We do have the Massachusetts versus EPA landmark decision of the Supreme Court. This was the prior Supreme Court, the one that still had a balance of judges on it. So this Supreme Court would have to overrule or substantially revise the Massachusetts versus EPA ruling. So we're going to have to watch very carefully what happens this year into next year into 2027 on the endangerment finding. All of the climate rules rest on what happens to the endangerment finding. So that's huge.

President Trump is moving to withdraw the United States from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change or UNFCCC treaty, which was ratified by the US Senate in 1992 and went into effect in 1993. Pictured above are world leaders during the 2024 UNFCCC Climate Action Summit, COP29, in Baku Azerbaijan. (Photo: President, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

O'NEILL: Energy has definitely been brought up as a major theme and concern for the Trump administration. You know, the President even declared an energy emergency. How did we see that reflected in the 2025 legal system?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, I mean, one of the most radical decisions that this administration has made is to go after renewable energy. Five of the major offshore wind farms have just been stopped by this administration. These are electric generation facilities or systems that supply electricity to millions of people up and down the East Coast. These wind farms were critical to stabilizing the grid system in a vast portion, almost half of the United States, because, of course, these data centers are imposing enormous demands on the electricity system as well as the water systems and land use systems. And these wind farms were critical components of being able to deal with those demands and still keep the lights on for average Americans. And the Trump administration, for reasons that defy reason or logic, have stopped them, and they're arguing that there's a national security risk. This is a favorite ploy of this administration because by declaring that, then they can say, well, the information is classified, so we don't have to share it with anybody. We don't have to share it with the courts. We don't have to share it with the public. We don't even have to share it with the Congress. It's amazing, isn't it? So that is now being challenged in court. An earlier decision of the courts ordered the administration to allow completion of one of these major offshore wind farms, the Revolution Farm, off of Rhode Island, and the court said there's no basis for this administration to stop the completion. It was 80% complete, and throw thousands of people out of work, by the way, that are finishing it up and linking it to the onshore facilities. So that's just one, one example of what this administration is doing. You can go across the country. They're stopping solar development on public land. They're stopping offshore wind on the Gulf Coast. They're opening up the Alaska wildlife refuge to oil and gas development for the first time in 50 years, etc. It's an all-out attack on the cleanest, most affordable, most efficient systems of energy generation that we have.

The People’s Climate March of 2017 brought together people concerned about President Trump’s environment policies. (Photo: Dcpeopleandeventsof2017, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: So Pat, 2025 is just year one of Trump 2.0, and we're heading into 2026 right now. There's a lot still to come, like we said, with the endangerment finding. What else are you keeping an eye out for that you think the Trump administration might move forward with in 2026?

PARENTEAU: Well, we know that they want to repeal the Rules implementing the Endangered Species Act. And what they're proposing to do would mean that restrictions on destruction of critical habitat would essentially be removed. And, as we know, the biodiversity crisis by itself, poses what, some scientists would say, is an existential threat to human life on earth. And the institutional damage that's being done to our systems of environmental regulation and protection are being decimated. The only way that that can be arrested, stopped, or at least slowed down, is if control of the Congress changes this year. It looks as if the house is definitely going to flip to the Democratic side. That will slow down any efforts by Trump in the Congress to further cripple these programs.

Pat Parenteau is a professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School. (Photo: Vermont Law and Graduate School)

O'NEILL: Pat you've been involved in environmental law for more than a half century at this point. What keeps you going?

PARENTEAU: Well, first of all, you can't quit. I mean, you know, the stakes are too great. What I like to say sometimes is, if I didn't have kids, I probably wouldn't care so much, because I'm not going to live to see all of these problems that I've been describing. You know, I hope to live a little while longer, but, you know, I'm not going to live forever, and some of the worst consequences are going to happen after I'm gone. But here's the thing, in addition to keeping up the good fight as long as I can and I will, there is reason to believe we can get beyond this situation. And the reason I say that is the technologies that we need we know to deal with 80% of the climate challenges we're facing right now, there's probably 100% of clean energy technologies that could deal with climate change. We know how to design systems and programs and laws and policies to do what we need to have done. We know how to do that. So that's the future that we all, I think, want to see happen, but it isn't going to happen accidentally or by osmosis. It's only going to happen if people, the public and voters in particular, insist that these things happen that need to happen. You know, climate change is a wicked, hard problem, but it can be dealt with. We can deal with these challenges, if we're willing to do it.

O'NEILL: Pat Parenteau is a former EPA Regional Council and emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School. As always, thank you so much for joining us, Pat.

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Aynsley. Good to be with you.

*Correction: The U.S. Senate ratified the UNFCCC treaty in 1992; the treaty went into effect in 1993.

Related links:

- Los Angeles Times | “Trump Withdraws U.S. From 66 International Organizations and Treaties, Including Major Climate Groups”

- The Guardian | “Trump Has Launched More Attacks on the Environment in 100 Days Than His Entire First Term”

- Living on Earth | “EPA Ignores Climate Dangers”

[MUSIC: Guitar Tribute Players, “Blowin’ In the Wind – Instrumental” on Acoustic Tribute to Bob Dylan, Cc Entertainment]

BELTRAN: Coming up, a down payment on investments to protect tropical forests, forever. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Guitar Tribute Players, “Blowin’ In the Wind – Instrumental” on Acoustic Tribute to Bob Dylan, Cc Entertainment]

Innovation to Fund Tropical Forest Protection

A tropical rainforest in the Danum Valley Conservation Area, Malaysia on the island of Borneo. (Photo: Jeremy Bezanger on Unsplash)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: So Aynsley, you and I have both been digging a little deeper into a topic we covered briefly on the show back in November.

O’NEILL: Yeah, back then Steve Curwood and Jenni Doering spoke with Michael Coe, a senior scientist from the Woodwell Climate Research Center about the United Nations climate talks, with a specific emphasis on the importance of forests and this new Tropical Forest Forever Facility launched by the COP30 host country Brazil.

Instead of relying on charity and government assistance to try and save tropical forests, the TFFF is an investment fund that will make money to pay countries to keep their forests standing, which I think is a pretty interesting concept all around. And I know you’ve been looking into how it might work from a financial standpoint, so what did you find out?

BELTRAN: Yeah, so this is fascinating. It uses a strategy common on Wall Street. Basically, it’s relying on bonds. Investors buy the equivalent of a guaranteed bond that pays them around four percent a year, and the TFFF then buys higher yielding bonds in less developed parts of the world, which these days, pay as much as seven or eight percent. That difference generates a gain which will be used to pay countries who keep their forests healthy.

O’NEILL: OK, but how are those bonds sold by the TFFF going to be guaranteed?

BELTRAN: So, that's where government subsidies come in. You know, just like the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or the FDIC guarantees your bank deposits in case your bank goes under, participating government bond purchases will back the TFFF portfolio. So if there are losses, the private bondholders still get paid. Here’s Chip Barber, he's the Director of Natural Resources, Governance and Policy at the World Resources Institute.

BARBER: All attempts in the past to come up with finance for forests have been based on the idea of grant funding from developed countries to developing countries. And there's been some amount of successes, but it's never really worked at scale. So, the idea here is, it's an investment fund.

BELTRAN: Brazil wants governments and sovereign wealth funds to buy $25 billion in TFFF bond equivalents, and they want the private sector to buy $100 billion, making for a $125 billion dollar investment fund once it’s fully capitalized.

O’NEILL: Which is a fair chunk of change. I mean that’s not nothing, especially if you are then going to put that into an investment portfolio.

BELTRAN: Yep. That's the pot of money they use to make money. They have to pay about $5 billion to the bondholders every year, but if they make double that from the higher yielding bonds they’ll still have half left over to pay countries. The high yield bonds they buy must come from governments or enterprises that are not actively destroying the environment, like big oil, and, of course, there will be expenses.

Still, on the scale of $3 or 4 or 5 billion earnings, that would be split among roughly 70 countries every year.

O’NEILL: Yeah, and, I mean, just for keeping your forests standing when you are currently being paid no money to keep your forests standing? That’s not bad.

BELTRAN: Yeah exactly, and Chip explained that this can be an attractive investment scheme for the private sector as well as the guaranteeing governments, since everyone gets a return if all goes well. And if there should be any losses, the private sector will get paid first. That’s because like the FDIC, the governments agree to take the first hit if anything goes wrong.

BARBER: So you have $25 billion in insurance, you are insulated from the risk, so it's low risk, fixed income, and you know, they're always looking for places to invest.

BELTRAN: Meanwhile governments get to avoid the much greater risk of losing forests.

BARBER: You know, there's a lot of critiques out there, but and they say, well, this is very risky, and it might not work, but not doing anything is very risky as well. I used to live in Indonesia, and Sumatra has just been inundated. You know, the climate change related weather things going on. There are thousands of people dying in flooding. And one of the rarest populations of orangutans was, a lot of it wiped out through floods. You know, if you do nothing about the tropical forest, you see a lot of damage to people and to the ecosystems.

BELTRAN: As Michael Coe, a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, explained when we first covered this back in November, forests are vital for a stable climate. They act not only as massive carbon stores, but also essentially the world’s air conditioners. So, trying to preserve them is worth this perceived risk.

The Tropical Forest Forever Facility is intended to fund the protection of tropical and subtropical forests by incentivizing countries to prevent degradation and deforestation. (Photo: Terpsichores, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

O’NEILL: Okay so ideally this fund is going to make, what, 3 to 5 billion dollars in profits each year and then it’s going to split those among eligible countries. But how would a country actually become eligible?

BELTRAN: So, a country must have a deforestation rate of 0.5% annually or lower. That means some could become eligible in the future if they start decreasing that number now. And then the country will get paid per hectare of standing tropical or subtropical forest every year, all of this measured by satellite data. If the data shows that the number of hectares has decreased, due to deforestation or degradation like a wildfire, they’ll get less money. It’s a pretty straightforward model.

O’NEILL: And, from what I’ve read, this isn’t anything like a carbon credit, right? You know, it’s not based on emissions or emissions reductions ?

BELTRAN: Yeah. Chip Barber of the World Resources Institute said it gives countries with lots of forest cover and low emissions a chance to be rewarded for keeping their forests.

BARBER: If you're Guyana or Suriname or Gabon or Republic of Congo, there's no additionality, as they call it, in the sense that, well, you already have a low deforestation rate. How do we get compensated for actually keeping our forest there? So, this is paying for keeping standing forest. That's why it's got forever in the title. Once you got good management and you're managing your forest, well, how do you, because it costs money to do that, how do you do that over time and do it in a way that provides sufficient incentives so that it's more worth your while to keep the forest standing than to cut it down and plant soybeans or palm oil or something else?

BELTRAN: Now Chip said there are some significant challenges with the pay-by-hectare model, like the world agreeing on a definition of what an “intact” hectare actually means as well as guaranteeing data transparency.

But that’s all in the works as the TFFF gets up and running.

O’NEILL: Now, Paloma, while you were talking with Chip, I was looking into this commitment that the fund has where they’ll give 20% of the money directly to local and indigenous communities.

BELTRAN: Yeah, and you talked to an indigenous leader who spoke at COP30, right? What did he think about this part of the TFFF design?

O’NEILL: Yeah, I spoke with Juan Carlos Jintiach, or Juanca. He’s a leader of the Shuar people, which is an indigenous group of about 170,000 who live in the Ecuadorian Amazon. He’s also the Executive Secretary of the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities, so he plays a big role in communicating on behalf of his people at international climate conferences. And one thing he underlined for me was how Indigenous communities are on the frontlines of preserving some of the world’s most fragile areas.

CARLOS: 80% of biodiversity is still in our hands, beautiful areas, but these areas has to be protected with us. Has to be coordinated with us.

O’NEILL: But historically these groups have been excluded from discussions about conservation and they are still struggling to get a seat at the table. So, from Juanca’s perspective, this proposal to give 20% of the fund’s benefits to indigenous groups, it’s a good start, but it’s not nearly enough.

CARLOS: It’s not fair. It’s not fair, because is in my power, 80%, 60%, or maybe 50% is something that maybe we do a good step, good initiative, and the youth or other generation will push for more. But we need to show something is good, that we need to begin with something.

The Shuar people are an Indigenous group living in the Ecuadorian region of the Amazon. They are among the local Indigenous groups that the TFFF has promised to allot 20% of the fund towards, helping to finance their traditional land stewardship. (Photo: Jlh249, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

O’NEILL: But before any of this can even get off the ground, the money needs to be in place, right? So where are we right now?

BELTRAN: Yeah, so we’re not there yet.

Of the initial $25 billion that the TFFF was hoping to get from global governments, it’s approaching $7 billion contributed so far, thanks to Brazil, Indonesia, France, Germany, Norway and a handful of other countries.

And then of course they need the private sector on board.

You know, there’s still a lot of logistics to sift through, but there’s also a lots of genuine excitement over this fund’s potential.

O’NEILL: Of course, I mean, if it can help save the climate, forests, and biodiversity, that’s pretty huge. Alright, well, thanks for researching this with me, Paloma.

BELTRAN: And thank you, Aynsley! We'll have to keep an eye out for how the Tropical Forest Forever Facility progresses over the coming months and years.

Related links:

- Learn more about the TFFF

- Listen to our original segment on the TFFF with Michael Coe

- More on Chip Barber at the World Resources Institute

- More on the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities, headed by Shuar leader Juan Carlos Jintiach

[MUSIC: Puebla Nuevo, “A Mi Lindo Ecuador” on Musica de Ecuador: Cajita de Musica, Promarket, Meta/Disconet]

Sea of Grass and the Disappearing Prairie

The American bison is a well-loved symbol of the prairie, and for good reason. Bison provide important ecosystem services, such as creating wallows for smaller animals and increasing grassland seed diversity. (Photo: Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0).

BELTRAN: Many different creatures call the American prairie home, from the lovable, shaggy buffalo to the endangered rusty patched bumblebee. Often overlooked, this prairie is actually one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world, with numbers of species rivaling even a tropical rainforest. But it’s also one of the most threatened. Today, just one percent of eastern tallgrass prairie remains, and western shortgrass prairie is disappearing at a rate of more than a million acres a year. Authors Josephine Marcotty and Dave Hage have teamed up to document the rapid destruction of these grasslands and the people working to save them. Their new book is Sea of Grass: The Conquest, Ruin, and Redemption of Nature on the American Prairie. Josephine Marcotty joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MARCOTTY: Thank you. Thank you for having me. It's a pleasure.

BELTRAN: So Josephine, how did the idea for Sea of Grass first come about?

MARCOTTY: I mean, like most people in this country, growing up, I really had little or no contact with the prairie because it was gone. I mean, I grew up in Michigan, I grew up in a suburb of Detroit, and the prairie was something I read about in books like Laura Ingalls Wilder, but not something that I had experienced. So it was only when I started exploring the prairie that was left and understanding what we had lost that inspired me to write, not only about agriculture, but about what we were losing by expanding agriculture in the Midwest.

BELTRAN: Can you describe the American prairie for us? You know, what does it feel like to visit such a place and what makes it special?

MARCOTTY: The tallgrass prairie, which is now almost completely gone, used to be an extraordinary place where grasses would be taller than a standing person, and in order to see over the top of them, you had to stand on top of a horse. It was a place where people could get lost, and often did in those tall grasses, or in the massive wetlands that used to occupy a third or 25% of the mid part of the country. It was an extraordinary place full of animals that we no longer have, wolves and bears and other carnivores, extraordinary birds. So I mean, the thing that I like about a prairie is the immense silence. All you hear is the sound of wind, and that enormous sense of space that you get, which is very similar to like, being out on a great lake or out on an ocean. Those are, of course, also lovely. But a grassland is just different.

Josephine Marcotty and Dave Hage’s latest book, Sea of Grass: The Conquest, Ruin, and Redemption of Nature on the American Prairie. (Photo: Courtesy of Josephine Marcotty).

BELTRAN: It sounds beautiful. Let's talk about one of the main characters in your book, the buffalo. Tell us about how you know, these large, lovable mammals fit into the narrative about grasslands and conservation.

MARCOTTY: So they are what biologists call a keystone species on the prairie. They have been around for millions of years. I mean, a long time ago, before Europeans arrived here, they were ginormous animals. They were just, they were huge. And they shared the grasslands with giant sloths and other animals that you know have long gone. But over time, they became a key part of the grassland ecosystem. So they come through and they eat the grass short and that creates an environment that's conducive to birds that like short grass, or insects that need short grass, and then they move on, and then the grass grows taller, and then that becomes an ecosystem for other animals that like taller grass. One of the things that they do is they wallow. If you've ever been to Yellowstone National Park or any other park where you can see bison, you'll see them roll over and just create these huge clouds of dust, and then when they leave, there's a little wallow. Those wallows are really important for collecting water when it rains, and scientists have found that there's unique species of animals and insects that will live in and around those wallows when they collect water. Bison, they carry seed across thousands, hundreds of miles when they eat the grass, and then they move the seed up to other parts of the of the grassland. And that's really important for evolution and mixing genetics amongst plants, so they create environment that's good for other species that use the same ecosystem.

BELTRAN: Yeah. So Sea of Grass centers around what you and Hage call the "paradox of the prairie." Please explain this concept and why it's especially relevant today.

MARCOTTY: So the paradox of the prairie is, I think, partly rooted in the fear that early colonialists had when they first encountered it. It is a vast grassland, and that's not something that most Europeans had experience with. They didn't like that openness. They were fearful of the wetlands. They would easily get lost. The winters were terrifying because they were cold and windy, but it was, at the same time, a remarkably fertile place. At first, they thought nothing would grow there because there were no forests, and they thought, well, there must be just bad soil. But it turned out to be the most productive soil in the world, as we know now, based on our agricultural output from those former grasslands. So that's one of the paradoxes.

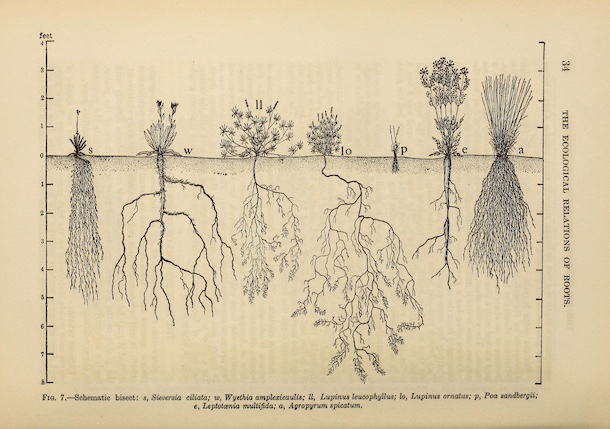

Prairie plants are highly effective at sequestering carbon because of their extensive root systems, which also help them withstand wildfires and prevent erosion. (Photo: John E. Weaver, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain).

BELTRAN: Yeah, I think most of us don't really equate prairies with biodiversity, but they are actually some of the richest ecosystems in the world. A recent study showed that the number of organisms present in grassland soil even rival the Amazon rainforest. What are some of the benefits of healthy prairies for humans and also for our planet?

MARCOTTY: Well, there is a whole world and a whole ecosystem beneath your feet when you're on a prairie, because the soil is so deep, and also because the roots of prairie plants are so long. I mean, Kentucky bluegrass, which is the kind of grass we often grow in our yards, is only about six inches deep, the roots. But other plants, like cup plant, those roots can extend down 15 feet into the soil, and so they create a whole universe of organisms around them, and that's an excellent way of sequestering and processing carbon, of sequestering and processing nitrogen, both of which are very important for world health in terms of air pollution and in terms of climate change. The world's grasslands contain more carbon than humans have released since the Industrial Revolution, more than the planet's forests and atmosphere.

BELTRAN: Wow.

MARCOTTY: So, and at the current rate of plowing up Western grasslands, we're plowing up about a million acres a year, and that's the equivalent of adding 11.2 million cars to the road every year.

BELTRAN: Wow. How are we losing our grasslands in the United States at such an astonishing rate?

MARCOTTY: So for many, many decades, intensive agriculture stopped at around the 98th parallel because it was too dry in the West to really graze crops properly. And instead, that's why we have cattle there. That's because it was good country for cattle and bison. But through genetic technology, we now are creating seeds, like for corn, that is much more capable of withstanding severe weather, that can thrive in dry conditions. So we now have the kinds of seeds that will allow us to grow crops in places where we could never grow them before. And the profits from that are much greater than from growing cattle. So you can sell a piece of land that has been plowed for much higher price than you can sell it if it hasn't been plowed.

Industrial farming is one of the driving forces behind prairie destruction. The practice of growing monoculture crops such as corn and soybeans uproots grasslands, depletes prairie soil, and increases the risk of pests, making farmers dependent on chemical fertilizers. (Photo: TwoScarsUp, Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0).

BELTRAN: So prairies are vanishing largely due to commercial agriculture replacing grasslands with monoculture crops. To what extent is industrial farming to blame for the disappearing of the prairies?

MARCOTTY: Yes, it's mostly agriculture. If you look at a map, or if you fly over the country, what you will see is farmland below you when you, when you fly over the Midwest. What's driven the loss of grasslands really is agriculture, and much of that, and in recent years, much of that is driven by ethanol, which is a fuel derived from corn. And ethanol was created in part to create a new market for corn, and the price of corn increased dramatically after those ethanol mandates were established by the federal government, and that has driven a lot of the expansion of agriculture, is just growing corn for our gas tanks.

BELTRAN: We’re speaking with Josephine Marcotty about her book, Sea of Grass: The Conquest, Ruin, and Redemption of Nature on the American Prairie. We’ll be right back with more. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

[MUSIC: Tallgrass Express String Band, “Last Stand of the Tallgrass Prairie” on Clean Curve of Hill Against Sky – Songs of the Kansas Flint Hills, Anne B. Wilson]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Punch Brothers, “Passepied (Debussy)” on The Phosphorescent Blues, orig. by Claude Debussy, 2015]

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

And we’re back now with Josephine Marcotty, coauthor of the book, Sea of Grass: The Conquest, Ruin, and Redemption of Nature on the American Prairie. And of course, the assault on prairies couldn't have been possible without the forced removal of Indigenous peoples from their native land. Describe for us how Native farming practices differ from industrial farming and how Indigenous peoples know to protect the land they live on.

MARCOTTY: So Native American people grew crops for their own consumption. So they would grow a variety of food depending on where they were. They would have corn, they would have beans, they would have squash. So they had much more diversity within their farming system, and so they could grow their food on a plot of land, and when the soil played out, they could move on to another place and grow food in another spot and let that area recover and become more fertile again. When European colonialists came in, they began to grow food for markets. So they grew far more food than they needed for themselves, and then they would sell the extra. Indians, they never, they didn't function like that. They didn't have like, a capitalist system. They were people who grew their food for themselves and and for their community, and they just grew what they needed for a season or for a year. And you know, bison were the primary source of food for Western Native Americans for many, many, many years, and they still are. In the last several decades, there has been a push to bring the bison from Yellowstone National Park and return them to the Native Americans and the tribal lands that used to rely on them, and this has been a great story of revival, not only for bison, but also for those native tribes to be able to have food sovereignty and their own source of food, and also to develop businesses around that source of food that they can generate income for their communities. And it's such a story of the underdog. You know, if you think of Native Americans as an, as an underdog, and bison as an underdog, and their ability to come back together and find strength together in restoring bisons to the tribal lands.

The Glacial Ridge National Wildlife Refuge was created in part out of a nearby agricultural town’s need for clean drinking water, emphasizing that restoring prairies is beneficial to farmers and conservationists alike. (Photo: Jasper Shide, Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0).

BELTRAN: So your book details the struggle between the farming industry and land conservation in the American West, but it sounds like restoring prairies is actually beneficial to farmers and to people everywhere. Could you describe that contradiction?

MARCOTTY: One of the contradictions is that we have many different viewpoints and opinions on what land is for. So farmers and the agricultural industry and farming communities often believe that land is best used to produce food and to produce crops, and that that is the economic engine of those small, rural communities. That's been true for hundreds of years. That is the basis of what drove much of colonialism across the country. But at the same time, one of the chapters we have in our book is about a prairie restoration in Northwest Minnesota called the Glacial Ridge. It is the largest prairie restoration in the country, it's like 24,000 acres. And The Nature Conservancy and the other organizations that helped restore that prairie, one of the reasons they were able to do that was because the city of tiny, little city of Crookston, which is primarily an agricultural economic city, needed a place to get clean drinking water, and they were able to put the city's drinking wells in this restored prairie, and know that they would never be contaminated with fertilizer or with other farm contaminants. So just clean drinking water alone is one real benefit. The other of course, is pollinators. I mean, the prairie is a place where you find more pollinators than almost anywhere else in the country, and we need those pollinators to pollinate the crops that we eat for food. But there are estimates that pollinators have declined by up to 25% in some parts of the country, and we're losing bumblebees at a high rate. The rusty patched bumblebee is on the endangered species list because it's disappeared in much of the prairie states. So those are just two of the ecosystem services that prairies can provide.

Bison ranchers are especially important to the health of prairies, but the steady income promised by corn makes it difficult for farmers to want to convert their land. (Photo: Lamar Buffalo Ranch, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain).

BELTRAN: And Josephine, you talk to multiple farmers, and you know, people within the agricultural industry for your book. What's their sentiment around the loss of the prairie and the loss of our grasslands?

MARCOTTY: I think many of them grieve it. I think that many people who live on the grasslands today love it the same way we all love the place where we grow up and appreciate its beauty and its wildlife and what it means to them culturally. But it's very difficult to compete with corn. And if you are a rancher that owns land, and you want to retire, and all of your pension, all of your savings, are essentially the land that you own, and the only way that you can sell it is to sell it to someone who wants to raise corn and soybeans on it, you're in kind of a bad spot. You don't have a lot of options in terms of finding another rancher who wants to raise cattle on it. It's going to be much easier in many places to sell it to someone who wants to raise corn. I think that farmers are caught in a system, just like the rest of us, we are all part of a food system that we created and that we rely on. They don't have a lot of room to experiment with different kinds of growing systems or different kinds of crops, and they often feel like they can't really afford to let grasslands be and to maintain grasslands. For them, land has to produce. They need to make money on it.

Marcotty encourages listeners to find a prairie to explore in order to understand the importance of preserving them. (Photo: Qwexcxewq, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0).

BELTRAN: And the farming industry relies heavily on support from the federal government, including from important legislation like the Farm Bill, which provides aid for farmers through programs like crop insurance and funding for research and development. How can the Farm Bill aid in preventing the loss and collapse of the American prairie while continuing to support farmers?

MARCOTTY: One of the things that would help a lot would be parity. So the Farm Bill is designed to help certain kinds of farmers, so the people who grow corn and soybeans and other commodities like cotton. It is not designed to help people who grow cattle. Grasslands need grazers. Ungulates have been a part of the grassland system for millions of years, and humans need ungulates, or animals on the land, because that is the way that we turn sunshine into protein, is those animals who graze on the grasslands. And it's enormously important for our diets and for our food system, but the protections that ranchers get, or anybody who raises animals on the land, is not equal to what you get if you are raising corn or soybeans. So if Congress was able to provide parity, so that all farmers and all producers, like whether you're a rancher or even a fisherman, if you also had the same kind of protections from risk that farmers have, that would give landowners much greater diversity in what they can grow on the land.

/content/2026-01-06/sog_Marcotty_hage_headshot.jpg

Josephine Marcotty and Dave Hage are co-authors of Sea of Grass: The Conquest, Ruin, and Redemption of Nature on the American Prairie. (Photos: Courtesy of Josephine Marcotty)

BELTRAN: What are some of the restoration efforts currently taking place across the country?

MARCOTTY: So there's a bill that's been introduced or is pending, called the Grassland Act, and it would help protect existing prairies by providing support for ranchers and by installing protections elsewhere in the law. So that is one thing we could do, is we could pass some policy that is designed to protect grasslands. Minnesota is one of the only states that has a statewide plan to protect prairies, and they're doing a lot here to buy up marginal cropland, mostly, and converting it back to prairies, and helping landowners who have prairies protect them and understand what they have and how to manage them. So that is really important, is for the nation and for the federal government to recognize that they are something of immense value that needs to be protected. You know, there are many ecosystems that are under threat. The prairie is just, is just one of them that we thought the risks to it were not recognized and needed to be recognized. But all of the outdoors is under threat, either from agriculture or development or from pollution, and the way to really protect all of them is for people to get outside and understand what they have and what they can do to stop whatever destruction is going on.

BELTRAN: Josephine Marcotty is an award-winning environmental writer. She's the co-author along with Dave Hage of Sea of Grass: The Conquest, Ruin, and Redemption of Nature on the American Prairie. Thanks for joining us!

MARCOTTY: My pleasure. Thank you.

[MUSIC: Gregory Alan Isakov, “San Luis” on Evening Machines, Dualtone Music Group 2018]

An Indigenous Bison Harvest

Buffalo herds were managed like Zoo animals in Denver for decades. It’s only been a few years since the city agreed to transfer any excess bison to local tribes so they can exercise their traditions. (Photo: Hart Van Denburg, Colorado Public Radio)

O’NEILL: Efforts to bring back bison, those huge grazers that once roamed the prairies in vast herds, are helping to revive Indigenous culture on lands across the US West. And this revival is taking place right in the city of Denver, which bought a handful of bison more than a century ago to display as a wild west novelty for tourists. Now, the herd has a new role – helping Denver’s Indigenous residents connect with their heritage. Colorado Public Radio’s Sam Brasch reports.

[SOUNDS OF SOMEONE SPEAKING IN A NATIVE LANGUAGE]

BRASCH: It’s a cool, clear morning when Lewis TallBull welcomes a crowd to Daniels Park, an area on a ridge south of Denver, overlooking the city’s skyline.

TALLBULL: I’d like to say good morning to each and every one of you. It’s good to see you.

BRASCH: TallBull is a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. He wears a flowing black shirt and moccasins. A fenced area nearby holds half of the city’s roughly 70 bison — known as buffalo in Native communities. For the last seven years, the city has allowed the TallBull Memorial Council — a group founded by Lewis’s grandfather — to slaughter one of those bison each fall.

TALLBULL: A young warrior's gonna lose his life today. But in that way, he's gonna provide life.

[SOUNDS OF PEOPLE WALKING]

BRASCH: After a ceremony, TallBull leads the crowd to the edge of the fence.

[SOUNDS OF GATE OPENING]

BRASCH: He takes a handful of men through a gate, towards a corral holding a 600-pound bull. We watch one of them steady a rifle. And then…

[GUNSHOT AND WAR CRY CHORUS SOUNDS]

BRASCH: The bison collapses to the ground. These kinds of ritual harvests are common on reservations. Many tribes keep bison to help restore the species — a species white settlers nearly exterminated because it sustained indigenous people.

Modern herds again provide a reliable food source. During the recent government shutdown, for example, some tribal governments slaughtered bison to make up for the loss of federal food benefits.

[SOUNDS OF PEOPLE CHATTING]

Bison are a big part of Native identity in the region. Tribes historically hunted the animals for meat, nutritional supplements, and ceremonial objects. (Photo: Hart Van Denburg, Colorado Public Radio)

TALLBULL: Us Indians who are forced to live in the city, we don't have anything like that.

BRASCH: Even though census data, it shows nearly three quarters of American Indians live in urban areas.

TALLBULL: That's what we're doing is, we're bringing these traditional ways and these bison harvest that only happen on reservations to the inner city, urban communities.

BRASCH: It’s a mission few cities can help with. Ryan Phillian manages the Daniels Park herd as a ranger with Denver Mountain Parks. He watches from a distance as elders pay their respect to the bison and a dance group begins to perform.

[SOUNDS OF DRUM PERFORMANCE]

PHILLIAN: This is uh, by far the biggest event that we’ve had down here and every year it seems to be getting bigger and bigger.

BRASCH: Originally kept as zoo animals, Denver moved its bison to mountain parks in the early 20th century. The grazing space is limited, though, so the city historically held an annual bison sale.

[SOUNDS OF DRUM PERFORMANCE]

PHILLIAN: ….where we would auction off our calves every single year. Uh, and you could have come out and bought a baby bison.

BRASCH: The city began to shift its management strategies by donating a bison per year to the TallBull Memorial Council. Three years later, they ended the auctions all together, opting to instead donate excess animals to tribal nations and continue holding these harvest events.

[SOUNDS OF A FRONT-LOADER]

BRASCH: Native organizers want to make these events as traditional as possible, but right now it still involves some modern equipment. A front-loader arrives to carry the buffalo to a butchering area. Once it’s laid on a tarp, another circle forms to watch participants take it apart.

MAN: Yeah, you guys can move in closer if you want.

BRASCH: The process will take six to eight hours, yielding enough meat for more than 150 people plus a skull for ceremonies and nutritional supplements made from ground organs. It’s an experience nine-year-old Malcolm Sanchez doesn’t want to miss.

[SOUNDS OF DRUM PERFORMANCE]

SANCHEZ: I think I might get in, get in on that. Um, cutting that bison.

BRASCH: You, you think you, you can do it?

SANCHEZ: I’ve cut things before.

BRASCH: And he’s not grossed out by the gory scene in front of us. He’s pumped for the meat.

SANCHEZ: My mom like makes this soup thing, right? She puts in bison, onions, and then she lets that, like, cook inside of a slow cooker and it’s so good.

Every year the TallBull Memorial Council in Denver organizes a ceremonial buffalo hunt, slaughtering an animal donated from Daniels Park. (Photo: Hart Van Denburg, Colorado Public Radio)

BRASCH: Sanchez says those meals make him proud to be Native, even though his family isn’t linked to a single tribe.

SANCHEZ: The only tribe I know I’m like part of is the Puebloan tribe. I don’t know the rest of ‘em because my family’s like a big mix.

BRASCH: That’s common in Denver — a city known as a crossroads for different Native people. TallBull is grateful the city has recognized its bison can help strengthen that community.

[SOUNDS OF PEOPLE CHATTING]

TALLBULL: Reestablishing our identity as Indian people, one percent each day is good enough. So this, this right here is a huge step for us and I think there’s only more to come.

BRASCH: He hopes to someday organize multiple harvests every year. That way, he says, more residents can affirm their Native ties, and Denver’s bison can recall their own heritage. Not as curious emblems of the Old West — but as food and cultural sustenance for Native people.

O’NEILL: That story by Sam Brasch comes to us from Colorado Public Radio.

Related links:

- Find this story on the Colorado Public Radio website

- See more photos of the ceremonial buffalo hunt

- Learn more about the history and importance of bison for Native tribes

- Read more about the InterTribal Buffalo Council

[MUSIC: Michael Maxwell, “Rocky Mountain High” on Rocky Mountain Memories – An Instrumental Tribute to John Denver, orig. by John Denver, Avalon 2013]

BELTRAN: Next time on Living on Earth, MacArthur Fellow Toby Kiers founded an organization that is mapping fungal communities around the world in the hopes of protecting this essential part of our ecosystems.

KIERS: It's not just about this one idea of like, let's make a map, but instead it's really about trying to use fungal data for applications for everything from policy to litigation to land management. And there's really a need right now to focus on what we call the three F's. So we used to just say flora and fauna, but now we're saying flora, fauna, and funga. It's really important for conservation efforts around the world to embrace that third F and start conserving fungi.

BELTRAN: That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Gia Margaret, “Hinoki Wood” on Romantic Piano, Composed by Margaret Comes, 2023]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Sophie Bokor, Jenni Doering, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, Julia Vaz, and El Wilson.

BELTRAN: We bid farewell to intern Jade Poli – thanks for sharing your curiosity and hard work! Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram, Threads and BlueSky @livingonearthradio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth