Innovation to Fund Tropical Forest Protection

Air Date: Week of January 9, 2026

A tropical rainforest in the Danum Valley Conservation Area, Malaysia on the island of Borneo. (Photo: Jeremy Bezanger on Unsplash)

The new Tropical Forest Forever Facility launched by Brazil at the 2025 UN climate talks is different from other efforts to protect nature in that it doesn’t rely on charity. Instead, it’s an investment fund that will pay dividends to both private investors and governments that keep their tropical and subtropical forest intact. Host Paloma Beltran walks Host Aynsley O’Neill through how it would work.

Transcript

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: So Aynsley, you and I have both been digging a little deeper into a topic we covered briefly on the show back in November.

O’NEILL: Yeah, back then Steve Curwood and Jenni Doering spoke with Michael Coe, a senior scientist from the Woodwell Climate Research Center about the United Nations climate talks, with a specific emphasis on the importance of forests and this new Tropical Forest Forever Facility launched by the COP30 host country Brazil.

Instead of relying on charity and government assistance to try and save tropical forests, the TFFF is an investment fund that will make money to pay countries to keep their forests standing, which I think is a pretty interesting concept all around. And I know you’ve been looking into how it might work from a financial standpoint, so what did you find out?

BELTRAN: Yeah, so this is fascinating. It uses a strategy common on Wall Street. Basically, it’s relying on bonds. Investors buy the equivalent of a guaranteed bond that pays them around four percent a year, and the TFFF then buys higher yielding bonds in less developed parts of the world, which these days, pay as much as seven or eight percent. That difference generates a gain which will be used to pay countries who keep their forests healthy.

O’NEILL: OK, but how are those bonds sold by the TFFF going to be guaranteed?

BELTRAN: So, that's where government subsidies come in. You know, just like the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or the FDIC guarantees your bank deposits in case your bank goes under, participating government bond purchases will back the TFFF portfolio. So if there are losses, the private bondholders still get paid. Here’s Chip Barber, he's the Director of Natural Resources, Governance and Policy at the World Resources Institute.

BARBER: All attempts in the past to come up with finance for forests have been based on the idea of grant funding from developed countries to developing countries. And there's been some amount of successes, but it's never really worked at scale. So, the idea here is, it's an investment fund.

BELTRAN: Brazil wants governments and sovereign wealth funds to buy $25 billion in TFFF bond equivalents, and they want the private sector to buy $100 billion, making for a $125 billion dollar investment fund once it’s fully capitalized.

O’NEILL: Which is a fair chunk of change. I mean that’s not nothing, especially if you are then going to put that into an investment portfolio.

BELTRAN: Yep. That's the pot of money they use to make money. They have to pay about $5 billion to the bondholders every year, but if they make double that from the higher yielding bonds they’ll still have half left over to pay countries. The high yield bonds they buy must come from governments or enterprises that are not actively destroying the environment, like big oil, and, of course, there will be expenses.

Still, on the scale of $3 or 4 or 5 billion earnings, that would be split among roughly 70 countries every year.

O’NEILL: Yeah, and, I mean, just for keeping your forests standing when you are currently being paid no money to keep your forests standing? That’s not bad.

BELTRAN: Yeah exactly, and Chip explained that this can be an attractive investment scheme for the private sector as well as the guaranteeing governments, since everyone gets a return if all goes well. And if there should be any losses, the private sector will get paid first. That’s because like the FDIC, the governments agree to take the first hit if anything goes wrong.

BARBER: So you have $25 billion in insurance, you are insulated from the risk, so it's low risk, fixed income, and you know, they're always looking for places to invest.

BELTRAN: Meanwhile governments get to avoid the much greater risk of losing forests.

BARBER: You know, there's a lot of critiques out there, but and they say, well, this is very risky, and it might not work, but not doing anything is very risky as well. I used to live in Indonesia, and Sumatra has just been inundated. You know, the climate change related weather things going on. There are thousands of people dying in flooding. And one of the rarest populations of orangutans was, a lot of it wiped out through floods. You know, if you do nothing about the tropical forest, you see a lot of damage to people and to the ecosystems.

BELTRAN: As Michael Coe, a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, explained when we first covered this back in November, forests are vital for a stable climate. They act not only as massive carbon stores, but also essentially the world’s air conditioners. So, trying to preserve them is worth this perceived risk.

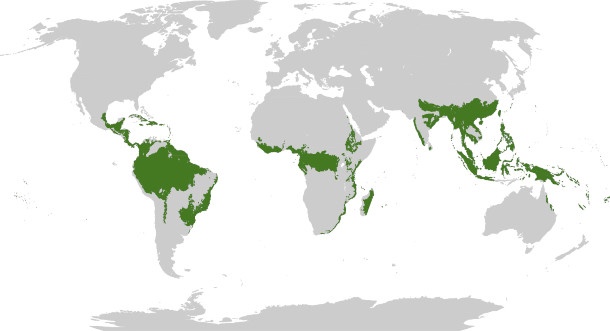

The Tropical Forest Forever Facility is intended to fund the protection of tropical and subtropical forests by incentivizing countries to prevent degradation and deforestation. (Photo: Terpsichores, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

O’NEILL: Okay so ideally this fund is going to make, what, 3 to 5 billion dollars in profits each year and then it’s going to split those among eligible countries. But how would a country actually become eligible?

BELTRAN: So, a country must have a deforestation rate of 0.5% annually or lower. That means some could become eligible in the future if they start decreasing that number now. And then the country will get paid per hectare of standing tropical or subtropical forest every year, all of this measured by satellite data. If the data shows that the number of hectares has decreased, due to deforestation or degradation like a wildfire, they’ll get less money. It’s a pretty straightforward model.

O’NEILL: And, from what I’ve read, this isn’t anything like a carbon credit, right? You know, it’s not based on emissions or emissions reductions ?

BELTRAN: Yeah. Chip Barber of the World Resources Institute said it gives countries with lots of forest cover and low emissions a chance to be rewarded for keeping their forests.

BARBER: If you're Guyana or Suriname or Gabon or Republic of Congo, there's no additionality, as they call it, in the sense that, well, you already have a low deforestation rate. How do we get compensated for actually keeping our forest there? So, this is paying for keeping standing forest. That's why it's got forever in the title. Once you got good management and you're managing your forest, well, how do you, because it costs money to do that, how do you do that over time and do it in a way that provides sufficient incentives so that it's more worth your while to keep the forest standing than to cut it down and plant soybeans or palm oil or something else?

BELTRAN: Now Chip said there are some significant challenges with the pay-by-hectare model, like the world agreeing on a definition of what an “intact” hectare actually means as well as guaranteeing data transparency.

But that’s all in the works as the TFFF gets up and running.

O’NEILL: Now, Paloma, while you were talking with Chip, I was looking into this commitment that the fund has where they’ll give 20% of the money directly to local and indigenous communities.

BELTRAN: Yeah, and you talked to an indigenous leader who spoke at COP30, right? What did he think about this part of the TFFF design?

O’NEILL: Yeah, I spoke with Juan Carlos Jintiach, or Juanca. He’s a leader of the Shuar people, which is an indigenous group of about 170,000 who live in the Ecuadorian Amazon. He’s also the Executive Secretary of the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities, so he plays a big role in communicating on behalf of his people at international climate conferences. And one thing he underlined for me was how Indigenous communities are on the frontlines of preserving some of the world’s most fragile areas.

CARLOS: 80% of biodiversity is still in our hands, beautiful areas, but these areas has to be protected with us. Has to be coordinated with us.

O’NEILL: But historically these groups have been excluded from discussions about conservation and they are still struggling to get a seat at the table. So, from Juanca’s perspective, this proposal to give 20% of the fund’s benefits to indigenous groups, it’s a good start, but it’s not nearly enough.

CARLOS: It’s not fair. It’s not fair, because is in my power, 80%, 60%, or maybe 50% is something that maybe we do a good step, good initiative, and the youth or other generation will push for more. But we need to show something is good, that we need to begin with something.

The Shuar people are an Indigenous group living in the Ecuadorian region of the Amazon. They are among the local Indigenous groups that the TFFF has promised to allot 20% of the fund towards, helping to finance their traditional land stewardship. (Photo: Jlh249, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

O’NEILL: But before any of this can even get off the ground, the money needs to be in place, right? So where are we right now?

BELTRAN: Yeah, so we’re not there yet.

Of the initial $25 billion that the TFFF was hoping to get from global governments, it’s approaching $7 billion contributed so far, thanks to Brazil, Indonesia, France, Germany, Norway and a handful of other countries.

And then of course they need the private sector on board.

You know, there’s still a lot of logistics to sift through, but there’s also a lots of genuine excitement over this fund’s potential.

O’NEILL: Of course, I mean, if it can help save the climate, forests, and biodiversity, that’s pretty huge. Alright, well, thanks for researching this with me, Paloma.

BELTRAN: And thank you, Aynsley! We'll have to keep an eye out for how the Tropical Forest Forever Facility progresses over the coming months and years.

Links

Listen to our original segment on the TFFF with Michael Coe

More on Chip Barber at the World Resources Institute

More on the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities, headed by Shuar leader Juan Carlos Jintiach

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth