February 16, 2018

Air Date: February 16, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Solar Market Takes a Dip

View the page for this story

The US solar market year saw a downturn in 2017 for the first time since 2010. But though the fall in jobs coincided with Donald Trump's first year as President, the Council on Foreign Relations’ solar expert Virun Sivaram tells host Steve Curwood that market trends and Capitol Hill policies are more responsible for shaping the future of American solar. (09:36)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood discuss grim news about the number of environmental activists killed in recent months, and why Toyota’s once wildly popular Prius has seen a steep sales slump. Then they remember the lovely Carolina parakeet, driven to extinction a century ago by farmers, loss of habitat and the demand for feathers on womens’ hats. (03:45)

More Pipelines, Fewer Salamanders

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

Large-scale natural gas pipelines often have environmental impacts, but so can smaller ones. In Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia thousands of small pipelines are being built to link fracking wells to the energy infrastructure. As the Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports, their construction is linked to muddier streams and the sharp decline in populations of the Eastern Hellbender salamander. (06:59)

It’s Raining Viruses, But Don’t Panic

View the page for this story

Untold numbers of viruses are swept up along with dust and water vapor, and a new study shows they travel in the atmosphere for thousands of miles. Microbiologist Curtis Suttle of the University of British Columbia tells host Steve Curwood there’s no need to panic as the vast majority of viruses only infect microbes, not humans. Indeed, these tiny packets of nucleic acids with a protein coat are actually vital to life on Earth, and may even be important for any extraterrestrial life as well. (07:10)

Frog Skin Fights the Flu

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

New research shows skin secretions from South Indian frogs can kill some flu strains. As Don Lyman reports in today’s Note on Emerging Science, the findings may point to an important resource for developing new antiviral drugs. (01:32)

The End of Epidemics

View the page for this story

Since a deadly influenza pandemic killed as many as 100 million people a century ago, medicine has come a long way, but we still have no truly effective vaccines against the seasonal flu which is proving serious this year. Host Steve Curwood discusses the shortfalls of our current approach to this disease with Harvard Medical School physician, Jonathan Quick. His new book, The End of Epidemics: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop It, focuses on containing outbreaks, and the need for a universal flu vaccine to control and prevent the next pandemic. (17:38)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Virun Sivaram, Curtis Suttle, Jonathan Quick

REPORTERS: Julie Grant, Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The US solar industry lost jobs last year for the first time in a decade – but the real danger isn’t Chinese competition or uncertain support – it’s lack of American investment in the future.

SIVARAM: There are lots of innovative, systemic fixes that we can make, and we really should be worried about solar collapsing under its own weight because right now solar is growing very healthily but in a decade or so, there could be so much of it that we won't know what to do with that solar.

CURWOOD: Also – how the boom in fracking is threatening a slimy amphibian.

LIPPS: They’re kind of a flattened, wrinkly sided, beady eyed salamander. Everything about them is made to live underneath a big rock in tight spots and darkness. Some people would say they’re so ugly they’re cute.

CURWOOD: Pipelines and the Eastern Hellbender and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Solar Market Takes a Dip

A large solar photovoltaic installation in Hunter Liggett, California. (Photo: U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Solar is under a cloud in America. Until last year sun power had a big run in job creation, but the Solar Foundation reports that 2017 saw about a four per cent decline in solar jobs, with installers taking the biggest hit. And recently the Trump administration moved to impose a tariff on imported photovoltaic solar panels, which will likely raise costs and further dampen consumer demand. Varun Sivaram is a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and author of “Taming the Sun: Innovations to Harness Solar Energy and Power the Planet.”

SIVARAM: Since 2010, the cost of solar power has fallen by over three quarters, and that's largely been fueled by cheap solar panels manufactured and exported from China, and elsewhere in Asia. So, thanks to this boon of really low cost solar panels, we've managed to bring down the cost of solar, both in the United States and worldwide. This is a global trend, and so as a result the market has just taken off. We've seen year-over-year growth almost every year. But then from 2016 to 2017 we saw a dip and a lot of commentators noted that dip happened to coincide with President Trump's first year in office.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Yeah, so, suddenly this market is booming, prices are low, why a drop then in solar jobs?

SIVARAM: It's actually not the case that Trump's policies caused this drop from 2016 to 2017. That's actually an artifact, a blip that if we had left alone would have quickly been smoothed out. See, in 2015, Congress went down to the wire on whether or not to extend a particular policy that was going to help solar installations - the investment tax credit. They decided at the last minute to extend the subsidy for five more years, but everybody thought it was going to expire in 2016. And so, all the solar developers moved up the timeline of their projects so they'd get them done in 2016 and took them out of the pipeline for 2017. So, we saw this momentary glut of solar installations in 2016 and a natural drop back in 2017. But that was a momentary blip, and so this had to do with Obama era policies and a congressional debate in 2015, nothing really to do with President Trump's policies. But that's not to say that President Trump's policies won't matter going forward.

CURWOOD: Yes, and now the Trump administration is in the process of imposing a tariff on solar panel imports, and there were fears that that would happen long before he actually implemented at the beginning of this year. So, what do you think that those fears contributed to the downturn in 2017?

SIVARAM: You know, I don't think those fears contributed much to the downturn in installations or jobs in 2017, but the fears and the actual impacts of the tariffs are definitely going to matter in 2018 going forward. The best estimate we've got is that from 2018 to 2022, the amount of solar installed in the United States will be about 11 percent less because of the tariffs than they would have been without those tariffs. The tariffs by the Trump administration are going to raise the cost of solar power in the US.

Sivaram's book is Taming the Sun: Innovations to Harness Solar Energy and Power the Planet. (Photo: courtesy of Varun Sivaram)

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about where most of the jobs come from in the solar industry.

SIVARAM: Over 80 percent of the jobs in the solar industry are deploying solar panels. This is building solar projects...you know, the fastest growing job category in the whole United States is solar panel installer. The jobs are not, by contrast, solar panel manufacturing. Once upon a time, the United States used to be one of the world's leading manufacturers of solar panels, but that’s no longer true, and that's why when the price of installing a solar panel goes up in the United States, you're going to see a net loss in jobs.

CURWOOD: Now, the Trump administration says that the tariff will help protect American jobs. To what extent is it true?

SIVARAM: That sounds right on paper. The Trump administration says, “Look, the Chinese government supported their domestic industry unfairly putting US businesses out of business”, so the Trump administration is now going to go and protect US businesses and try and bring back manufacturing jobs. Unfortunately, that's not how it's going to play out in reality. The Trump administration tariffs only last four years, and they actually get sliced in half over those four years and that's not very much investment certainty for a US company to go set up a big expensive factory in the United States. So, I don't actually expect these tariffs to help create manufacturing jobs in the US. This is kind of like closing the barn door after the horse has bolted. The Chinese state support came a decade ago, but now Chinese and Asian manufacturers are able to just achieve low cost by themselves without government incentives, and for the US to catch up it's not enough to put these kind of half-hearted tariffs on imported solar panels. It won't encourage investment in the US. It'll probably reduce installations and we gotta help bring it back.

CURWOOD: OK. So, what's the answer?

Nearly 80% of the jobs in the solar industry come from the demand-side sector, through jobs such as installation. (Photo: Melanie Bateman, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

SIVARAM: That answer is what I write about my book, "Taming the Sun". I argue that it's going to take innovation in solar for the United States to once again lead in the industry and capture share of this growing market, and unless we invest in innovation and the research development and demonstration of brand new technologies, we're not going to be able to compete at China's own game. China's own game is manufacturing existing old technology at enormous scale. For us to breakthrough, we're going to need innovative new technologies. I've worked on some of these as a physicist in the lab and they are phenomenal technologies.

CURWOOD: Oh?

SIVARAM: For example, the front-runner technology known as Perovskite solar panels, these could enable low-cost highly efficient flexible coatings. You could one day paint your house with a solar coating. You could wrap skyscrapers with this. You could put it on weak roofs in the developing world. There are remarkable technologies that are there in laboratories that the United States could commercialize.

CURWOOD: Now, your analysis says that the slowdown really began, frankly, linked to Republican opposition to extending the solar tax credits on Capitol Hill during the Obama years and then now compounded with the tariff that Mr. Trump is imposing. At the end of the day, how much does that put us behind our goals, say, to respond to the Paris climate agreement?

SIVARAM: I actually fault both sides here. I think that the tax credits themselves, which were scheduled to expire in a massive way in 2016, created this window of policy uncertainty. Sure, Republicans opposed them, and therefore it went down to the wire on whether we were going to extend them or not, but frankly going forward the tax credits didn't need to be extended for that long. Solar is already economical in the United States and we ought to have seen a quicker ramp down of the tax credits based on what's economical and not. So, I don't want to pin this on Republicans and say that Republicans oppose solar and, therefore, solar's not doing well. This is a bipartisan issue. Republicans and Democrats have useful things to say on it. I do believe that the Trump administration is taking the wrong approach. It should not pull out of Paris at all, it absolutely should not be imposing tariffs, and it should be investing far more in research and development than it plans to. But let's not turn this into a Republicans against Democrats issue on support for solar because I actually think both sides get some things right and some things wrong.

CURWOOD: So, what would you say are the biggest threats to the solar industry right now?

SIVARAM: I think the solar industry's biggest threat is itself. You know, over the next decade, solar energy is going to become very hard for the grid to tolerate. That's why we've got to plan right now, so that solar doesn't become a victim of its own success. See, when solar's one percent or less of total electricity, it's not that hard to worry about, it's not that hard to integrate it onto the grid. But what if solar gets to 10 or 20 or 30 percent? At that point we're going to have so much solar it'll be a nuisance to integrate this highly volatile energy source. And that's why, you know, we keep coming back to the same things. We need far cheaper solar, revolutionary technologies, and we need much better systems, you know, cross continental transmission grids that can take solar from places of excess to places of scarcity or ways, for example, to intelligently turn on and off millions of thermostats and water heaters and space heaters so that they can mop up excess solar electricity on the grid and use it when it's available. There are lots of innovative systemic fixes that we can make and we really should be worried about solar collapsing under its own weight because right now, it's growing very healthily, but in a decade or so there could be so much of it that we don't know what to do with that solar, and unless we prepare for that right now we'll find ourselves in a difficult situation.

CURWOOD: The current budget advanced by the Trump administration would really cut the Department of Energy's funding for this kind of research.

Varun Sivaram is a science and technology fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. (Photo: Courtesy of Council on Foreign Relations)

SIVARAM: Absolutely. I think it is, it would be catastrophic if Congress accepted the president's request, you know, it just came out this week to cut renewable energy research and development by over two-thirds, to cut ARPA-e, this agency that does farsighted technology bets across energy technologies. They want to eliminate it entirely. It would be catastrophic. Fortunately, there is basically zero chance that Congress accepts this budget recommendation. Last year, the Trump administration did the same thing. Congress categorically rejected it, it was Congressional Republicans who rejected it, Senator Lamar Alexander, Republican, who said, absolutely not...we believe in funding the kinds of transformative energy innovations that ARPA-e funds. I'm relieved that Congress so far has acted as a bulwark against President Trump's energy innovation recommendations, which would just be catastrophic.

CURWOOD: Varun Sivaram is a Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations whose new book is called "Taming the Sun: Innovations to Harness Solar Energy and Power of the Planet”. Varun, thanks so much for taking the time.

SIVARAM: Steve, thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- 2017 Solar Job Census

- Varun Sivaram Profile

Beyond The Headlines

The Carolina Parakeet was driven to extinction in 1918 in part because its feathers were in demand for ladies’ hats at the time. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Let’s take a look beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and DailyClimate dot org. He’s on the line from Atlanta Georgia. How are you doing, Peter?

DYKSTRA: I’m doing alright, Steve, how about you?

CURWOOD: Things are pretty good, it’s kinda cold though still. So, what do you have for us? What’s going on?

DYKSTRA: Well, let’s start with some down news but we have to report it. The non-government group, Global Witness, said that in 2017, 197 environmental activists around the world were murdered.

CURWOOD: Oh my. So where, why, who?

DYKSTRA: Bear in mind that’s four a week. These are peasants, landowners, farmers, local activists trying to protect their homes. Working against dam projects, big logging operations, big mining operations. 197. Also just this past week there’s a man named Esmond Bradley Martin. He was a legend in hunting down smuggling paths for rhino horn and elephant tusks. He was stabbed to death in his bed in Nairobi.

Sales of the Toyota Prius have hit a slump in the last few years. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: And, Peter, I thought I saw something in the news about an Iranian environmentalist who was killed.

DYKSTRA: Yes, a Canadian Iranian professor who was named Kavous Seyed Emami. He ran and founded the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation. He was brought in on espionage charges, it’s not really clear what the espionage could have possibly been and then he was found hanged in his solitary confinement cell. The family is not buying at all that he hanged himself.

CURWOOD: No, it doesn’t sound like that to me. Hey, what else is going on?

DYKSTRA: Well, let’s turn stateside and look at the Prius. You know, the Prius was a phenomenon a few years ago. 2012 sold 236,000 cars. 2017 that number fell by more than half - 108,000 cars.

CURWOOD: So, Toyota is having a sales problem with the Prius? What’s going on?

DYKSTRA: Well, there are a lot of things going on. Number one, the whole hybrid notion has spread to larger cars like the Camry, the Rav 4, which is a crossover, is selling. So, that’s taking some of the lightning away from Prius but also you have cheap gas. It stayed cheap and if gas is cheap people have less motive to buy a fuel efficient car. Fuel efficiency standards have gone up in general -- although watch out for that to change in the Trump administration. Competition from other car makers. Not just hybrids but also EVs. And the Prius designs seem to be less enchanting to the public than they were a few years ago.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I got to say it’s not the most lovely car on the road right now. Hey, what do you have for us from the history vault?

Iranian-Canadian environmentalist Kavous Seyed Emami was found hanged in his jail cell in Iran. (Photo released by Emami’s family)

DYKSTRA: Something that happened 100 years ago, kind of a sad event. The Carolina Parakeet used to swarm over the eastern US. It was the only parakeet species that’s native to North America. It met its demise over the years. Number one, farmers hated the Carolina Parakeet because they ate apples, they ate other seeds they ate corn seed. Another reason is that the forests that they thrived in were being taken down for farmland, and cities, and factories. And finally, the third thing is that the Carolina Parakeet, like most parakeets, had beautiful colorful plumage and that plumage was prized for lady’s hats a century ago. And the Carolina Parakeet died out – the last one died in the Cincinnati Zoo in the year 1918.

CURWOOD: And they’re completely extinct. Why didn’t someone breed them or something?

DYKSTRA: Well, they were pretty easy to capture and the conventional wisdom is they would have been pretty easy to captive breed but that kind of thing just didn’t happen in 1918.

CURWOOD: Well, thanks Peter. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News. That’s EHN dot org and Daily Climate dot org. We’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Ok, Steve, thanks a lot. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website. LOE dot org.

Related links:

- The Guardian: 197 environmental activists were killed worldwide in 2017

- The Guardian:: “Top ivory investigator murdered in Kenya”

- Los Angeles Times: “Environmentalists are the latest targets for arrest in Iran. One died in prison, officials say”

- Green Car Reports: “Toyota Prius hybrid sales have tanked: here are 4 reasons why”

- All About Birds: “Carolina Parakeet: Removal Of A ‘Menace’”

[MUSIC: L. Strachey, “Nothing Could Be Finer Than To Be In Carolina” not commercially available, composed by Walter Donaldson and Gus Kahn

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_18IpFYUhHk]

CURWOOD: Coming up, salamanders could be the proverbial canaries in the coal mine for pipeline construction. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: L. Strachey, “Nothing Could Be Finer Than To Be In Carolina” not commercially available, composed by Walter Donaldson and Gus Kahn

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_18IpFYUhHk]

More Pipelines, Fewer Salamanders

The Eastern Hellbender is the largest salamander in North America, reaching lengths of up to 24 inches. It’s also the official amphibian of Pennsylvania. (Photo: Dave Herasimtschuk / Freshwaters Illustrated)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Pipelines that can carry huge amounts of oil and gas over hundreds of miles get a lot of coverage in the news media, but small ones get scant attention, even though their sheer numbers make for a major impact. In Pennsylvania and Ohio, the construction of thousands of minor pipelines to connect fracking well pads to the larger distribution system could be driving a little known amphibian to extinction. The Allegheny Front's Julie Grant has our story.

[SCHOOL CHILDEN CHATTING AND LAUGHING]

GRANT: High school students file into Nicole Costello’s small reptiles class at the Penta Career Center in Toledo, Ohio.

COSTELLO: Alright, welcome welcome to this lovely Tuesday. Did everybody sign in?...

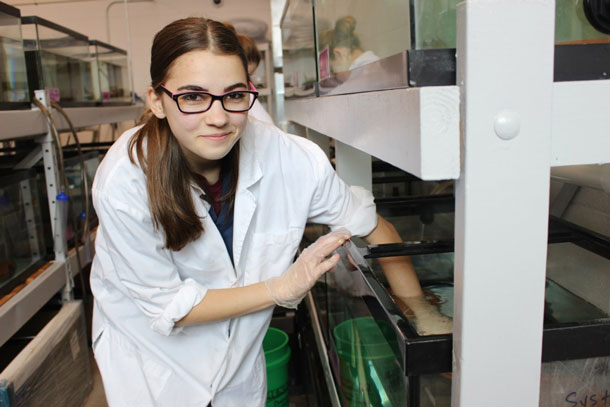

GRANT: They’re learning firsthand how to foster an aquatic species that experts say is in decline - the Eastern Hellbender Salamander. In a bio-secured room on campus, 18 year old Theresa Paff and other students clean the glass tanks, weigh and cut up worms to feed to the young Hellbenders they’re raising. Paff picks up one that’s 3 year old.

18-year-old Theresa Paff cares for Eastern Hellbender salamanders at the Penta Career Center in Toledo, Ohio. (Photo: Julie Grant)

PAFF: It’s really hard to hold. They always like to move, and they’re so slimy and slippery.

GRANT: These are not the cute, colorful little salamanders that might come to mind. They’re brown and mottled.

LIPPS: Some people would say they’re so ugly they’re cute.

GRANT: Greg Lipps is an expert on Hellbenders at Ohio State University, and works with the high school program. He says there’s good reason they’re often called snot otters, Allegheny alligators, or old lasagne sides.

LIPPS: They’re kind of a flattened, wrinkly sided, beady eyed salamander. Everything about them is made to live underneath a big rock in tight spots and darkness.

GRANT: Lipps says the adults can get big - over two feet long, and can live 35 years or more. They’re mainly found in streams along the Appalachian Mountains in Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. And these guys are tough, the species has survived for millions of years - which is why Lipps was so concerned when he and a colleague found an 82-percent drop in their populations in Ohio… they just weren’t finding many young Hellbenders.

LIPPS: It’s kind of like if the whole world became a nursing home overnight. You know that the end is near if you don’t have any youngsters in these populations.

GRANT: Researchers suspect the problem has to do with increased sediment in the water. Young hellbenders are thought to live in little spaces in gravel beds, that are easily filled with sediment. Lipps has watched as waterways, especially in the steep hills of eastern Ohio, near the Pennsylvania and West Virginia borders, have gotten muddier.

The reason seems obvious to him: pipelines.

LIPPS: And you can trace this, it’s not rocket science when you see the muddy water to drive upstream until you see clear water and then figure out well, what’s happening, where’s the in between? And when I’ve done that it’s been pipeline construction.”

(SOUND OF PLANE ENGINE FIRING UP)

GRANT: To get a better picture of the gas pipeline boom here, Ted Auch of Fractracker, a non-profit that tracks the fracking industry, has organized a tour by plane of West Virginia and Ohio.

(SOUND INSIDE PLANE)

GRANT: As we get into the air, he’s floored by how many hillsides are cleared of trees, to make way for pipelines.

AUCH: Look at this one, Julie, look how zig and zagging this puppy is...”

A pipeline crossing Captina Creek. (Photo: Liza Butler)

GRANT: You can see these gathering lines connecting every well pad and compressor station. Ohio and Pennsylvania are among the states with the most gathering lines in the country - each with more than 20-thousand miles of them. Pipeline companies are supposed to replant the pipeline corridors. But Auch says many don’t.

AUCH: See, Julie, that’s all pipelines. And they have not hydro-seeded that, you see what I’m talking about? And they’ve got that apron, that tarping material that’s supposed to prevent the loading of sediment down. But they didn’t hydroseed any of that.

GRANT: On the ground in eastern Ohio, the hills are alive with pipeline construction. To the north, are the bigger transmission lines - the Mariner East and the Rover. Smaller gathering lines have names like the Hot Sauce Hustle, and Dr. Awkward. Ohio State researcher Greg Lipps says when companies strip these steep hillsides of forest for pipelines, it can destroy his team’s efforts to restore stream banks, and protect the habitat for Eastern Hellbenders and other aquatic species.

LIPPS: What you create is effectively what can be a river of mud every time it rains. It’s really a problem. And the amount of silt and sediment that can come from a pipeline cut and from an eroding stream bank is immense.

(WATER SOUNDS, BIRDS BY CREEK)

GRANT: Many of the new pipelines also cross the streams, themselves. Like here in Captina Creek, a high-quality stream and home to Hellbenders. It empties into the Ohio River. The pipeline companies either bore underneath the stream bed or dig right through the water. According to an Allegheny Front review of applications to the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, the state has issued at least 13 permits, including 66 pipeline stream crossings in the Captina Creek watershed alone since 2014.

Harry Kallipolitis manages the Ohio EPA’s permitting process. His agency, like regulators in here Pennsylvania, is required by the Clean Water Act to certify that pipeline crossings are not going to jeopardize stream quality.

KALLIPOLITIS: We evaluate what benefits to society it may have and weight that against the potential impacts to water quality. Our lower bar is not jeopardizing the existing use or how that stream is performing. And we do authorize the potential lowering of water quality with potential mitigation to make up for that loss.

MarkWest cryogenic and fractionation plant that processes natural gas in Wetzel County, WV. (Photo: Renee Rosensteel)

GRANT: Kallipolitis says there’s no regulation looking at the cumulative impacts of the new lines. But he says they have not seen impacts on any streams from multiple pipeline crossings.

KALLIPOLITIS: We evaluate a lot of streams in Ohio, and you know to my knowledge we haven’t had any of those reports come back to us and say that the stream is jeopardized by multiple crossings associated with pipeline projects.

GRANT: Still, Kallipolitis says the Ohio EPA will propose new sediment regulations for pipelines in the coming months. And researchers at West Virginia University are starting to look at ways to reduce the environmental impacts of pipelines. Michael Strager is a professor of resource economics. In a study that just got funded, he plans to use GIS technology and drones to map pipelines in the region, and then his colleague will match the locations with water quality data in nearby streams.

KALLIPOLITIS: So I think how our work is going to be useful is to really aid in the permitting process as part of a planning approach to really direct this industry to places where we can potentially have less of an impact than others.

GRANT: Like the students at Penta Career Center, these West Virginia researchers want the waterways clean enough so species like the Eastern Hellbenders can survive here. The high schoolers will join experts, and release the young salamanders into the streams of eastern Ohio over the summer. I’m Julie Grant.

CURWOOD: Julie Grant reports for the Pennsylvania public radio project, the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Allegheny Front: “Are Pipelines to Blame for Decline in Ancient Salamanders?”

- How to protect and conserve the Eastern Hellbender

- The American Petroleum Institute’s Natural Gas Industry Impact Report

- Ohio EPA’s water quality study of the Captina Creek watershed

[MUSIC: Courtney Granger, “What Are They Doing In Heaven Today” on Beneath Still Waters, public domain/arr.Courtney Granger, Valcour Records]

It’s Raining Viruses, But Don’t Panic

Viruses can travel for thousands of miles around the Earth via dust clouds and marine aerosols, a new study says. (Image: LOE, composed from Earth image by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and bacteriophage model by Adenosine, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: This flu season is one of the worst in recent years, and we’ll have more on the need for a universal flu vaccine later in the broadcast. Influenza is a virus of course, and must have a host to survive. Fortunately it is a rare virus compared to those that constantly rain down from the sky. Yes, new research shows billions of viruses hitch rides for sometimes thousands of miles in dust clouds and water droplets whipped up by wind. Almost all of these sky-borne viruses are harmless to humans, and even the small number of flu viruses in the sky don’t pose the same dangers as sneezing people and infected door knobs. Curtis Suttle co-authored a study based on data collected in Spain and published in the International Society for Microbial Ecology Journal. He teaches at the University of British Columbia. Professor, welcome to Living on Earth!

SUTTLE: Thanks, Steve. It's a pleasure to meet you.

CURWOOD: So, the first thing I want to know, Professor, is how concerned should we be about all those viruses traveling so far and swirling up there in the atmosphere?

SUTTLE: Honestly, I don't think we really need to be concerned at all. These are bacteria and viruses which are not pathogens of humans. These are essentially the microbes that exist everywhere on the planet.

CURWOOD: What about the flu?

Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of virus particles in seawater. These get swept up from the surface of the sea to high in the atmosphere, where they can be swept around the Earth. (Photo: Curtis Suttle)

SUTTLE: So, things like influenza, you know, viruses which infect humans certainly they're of concern. So, if we get the wrong virus that's absolutely something we need to be concerned with. But the viruses that we see circulating high up in the atmosphere, the things that they're infecting almost exclusively are other microbes, primarily bacteria, and so one of the things that's really important to recognize is though there are bad viruses that will make us sick because every time you step outside, you're literally inhaling millions of viruses, right, that go into your body. If you take a swim in the ocean, just the amount of water that you take into your mouth would be the same amount of viruses that would be somewhere between the population of Canada and the United States, probably somewhere between 30 and a couple of hundred million viruses that you would ingest, and those viruses don't make us sick, in fact, they're just part of the natural ecosystem. The vast majority of viruses on this planet, the host organisms that they’re affecting are other microbes.

CURWOOD: Well, that makes me feel better. By the way, what is a virus exactly?

SUTTLE: So, viruses are obligate pathogens. They can only replicate by infecting living organisms. They're pretty simple by many standards, they essentially have a protein coat which surrounds some nucleic acids and when they find a suitable host organism, and they're usually highly specific, so they infect only one type of host, then they will introduce that nucleic acid into the host and they will begin to grow.

A researcher with a microbe collector system at the Astrophysics Observatory of Sierra Nevada (Spain). On the left is a wet collector (covered) and on the right is a dry collector. (Photo: courtesy of Isabel Reche Cañabate)

CURWOOD: So, how many viruses are coming out of the sky every day?

SUTTLE: Yeah, what's really remarkable is if we go up above the planetary boundary layer, we will typically find close to a billion viruses on average, every square yard per day that are settling out of the atmosphere, and so when I say above the planetary boundary layer we're talking about elevations say of 9,000 feet or 3,000 thousand meters or so, so above that layer, so high up in the atmosphere. Even that high up, we're seeing these massive amounts of viruses, and if we come down to the surface, like, if you're in a city or in Boston or something like that, you can be sure that there's a lot more viruses that are settling out of the atmosphere than a billion per square yard per day.

Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of bacteriophage viruses attached to a bacterial cell wall. (Photo: Dr. Graham Beards, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Professor Suttle, how is it that viruses can travel so far when they get up into the atmosphere? I mean, your paper talks about them, maybe they can even circle the planet!

SUTTLE: You have these particles, these aerosols that are swept off the surface of the ocean or the surface of land, in this case in North Africa, many of them make their way up high into the atmosphere, and once they're that high in the atmosphere and they're so small, they essentially can blow around unimpeded for long, long distances. You know, it's even been speculated that because there are so many out there that maybe there's actually organisms that this is their home, right, that they're suspended up there above the planetary boundary layer.

CURWOOD: So, what would they be doing for food?

SUTTLE: Well, there's all this dust, for example, so the microbes, that's what they need. They need sort of organic material that they can grow on, and there's lots and lots of particles. So, if they were swept high potentially they could be growing on organic material. And also off the surface of the ocean, there's all these aerosols that are traveling high up into the atmosphere and so, I mean, nobody has demonstrated this yet, but I mean it's conceivable that they could be living up there.

CURWOOD: What's the role that viruses play to life on Earth and the evolution of life here. If they can travel like this everywhere, what does that mean?

SUTTLE: Yeah, so, what I always like to think about is that for the first three-and-a-half billion years that life has been on Earth, it was entirely microbial, and so there really were only bacteria and another microbe called Archaea and the viruses which infect them.

Spain’s Sierra Nevada Mountains before and after a dust intrusion event covered their snow-capped peaks. (Photo: Joshua Stevens / NASA Earth Observatory)

And so, viruses were the predators in the system, and the only predators in the system, and multicellular life really didn't come on the scene until a few hundred million years ago. So, for almost the entire existence of life on the planet, the whole ecosystem has been microbial. And so, viruses and the organisms that they infect are extremely highly coevolved. And as part of that process, viruses are really really good at moving genetic information around. And so, in fact, the original field of biotechnology was the result that you could use a virus and you could move genetic information from one organism to another. You know, the original genetic engineering, if you like, was using viruses to actually move genes around among organisms. They do this naturally, and so if we look at our own nucleic acids, our own DNA in our own bodies, a large percentage of it is actually viruses which are still stuck in our genome -- for example, the placenta of mammals contains a protein which was donated from viruses. Some of the major components of our nervous system were actually the result of genetic information donated from viruses. So, viruses are masters at moving genetic information around and as a result of that, they've been absolutely crucial to the evolution of all organisms.

CURWOOD: Interesting. Now, these viruses get lofted up into the atmosphere. If they can get up so high, could they, well, could they be getting into space?

Curtis Suttle is a professor at the University of British Columbia (Photo: University of British Columbia)

SUTTLE: Absolutely, and so it's interesting, we’ve done work with NASA and the Canadian space agency before and when I have served on these committees for years and years and years, I’d say, “If we want to look for life on other planets, we should probably be looking for viruses”, because theory tells us that if we have living organisms, we'll always have these kind of parasites and pathogens they replicate on. They are by far the most abundant biological entities on Earth and presumably elsewhere as well, so you typically would find 10 times as many virus as the organisms that they infect, and because they are so small and they aerosolize so high up into the atmosphere and we have technologies where we can really detect a single virus particle, and so I've often argued that if you're looking for life on other planets, what we should be doing is going into the atmosphere and seeing if we can detect anything that looks like a virus because they're likely going to be there in the highest abundance and it would be absolutely indicative of life.

CURWOOD: Curtis Suttle is a virologist and teaches at the University of British Columbia. Thanks so much, professor, for taking the time.

SUTTLE: Thanks. It's been absolutely my pleasure.

Related links:

- EurekaAlert!: “Viruses – lots of them – are falling from the sky”

- Journal article: “Deposition rates of viruses and bacteria above the atmospheric boundary layer”

- University of British Columbia Professor Curtis Suttle

- Co-author Isabel Reche Cañabate of the Universidad de Granada

[MUSIC: Courtney Granger, “What Are They Doing In Heaven Today” on Beneath Still Waters, public domain/arr. Courtney Granger, Valcour Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, how frogs might provide a defense against the flu. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Margot Chamberlain, “Pentatonic Improvisation” on Golden Threads-Harp and Song, composed by Margot Chamberlain, songandharp@gmail.com]

Frog Skin Fights the Flu

The Indian frog Hydrophylax bahuvistara secretes antiviral peptides from its skin. (Photo: YukioSanjo, Wikimedia Commons CC-BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. In a minute – why the annual flu shot sometimes misses the mark – but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[MUSIC: SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: Brilliantly colored poison dart frogs are notorious for the deadly poisons they secrete, but now scientists have discovered South Indian frogs are also deadly -- to flu viruses. Researchers from Emory University’s Vaccine Center and the Rajiv Gandhi Center for Biotechnology in India found that peptides - short chains of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins -- from the skin mucus of these frogs kill the H1 flu strain.

Scientists knew that frogs’ skin secreted "host defense peptides" that protect them against certain bacteria. But this new finding implies that the skin peptides may protect against viruses as well. The scientists named one of the antiviral peptides “urumin”, after an ancient Indian whip-like sword called an “urumi”. Urumin appears to disrupt the integrity of the flu virus by binding to a protein called hemagglutinin. Given intranasally, urumin protected unvaccinated mice against lethal doses of some H1 flu viruses, though it doesn't work for all strains.

The scientists think anti-flu peptides could be useful when vaccines are unavailable, in the case of a new pandemic strain of flu, or when circulating strains become resistant to current drugs. Now the researchers are looking for frog-derived peptides that might be active against other viruses, such as dengue fever and the Zika virus. That’s this week’s note on emerging science, I’m Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Related links:

- Original study in the journal Immunity

- CNN/i>: “Researchers use frog mucus to fight the flu”

The End of Epidemics

An emergency hospital at Camp Funston, Kansas where nurses and doctors tended to those infected with the 1918 Spanish Flu. The pandemic killed between 50-100 million people globally. (Photo: Otis Historical Archives Nat'l Museum of Health & Medicine - NCP 1603, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: South Indian frogs may prove key to making a better flu vaccine, but it won’t help us with this season’s particularly nasty outbreak. Influenza is widespread in 48 states and is proving to be particularly deadly, with 4,000 related deaths in just one week in January. Thankfully this year is not as bad as the so-called Spanish Flu pandemic at the end of World War One that sickened a third of the world’s population and killed perhaps as many as 100 million people. And despite advances in medicine since then, we are still far from safely containing the next major pandemic. That’s according to global health physician, Jonathan Quick, who calls this challenging flu season ‘a teachable moment.’ In his new book, The End of Epidemics: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop It, Dr. Quick offers a road map for local, national and international actions that could prevent killer outbreaks in the future. He teaches at Harvard Medical School and joins us now - welcome to Living on Earth!

QUICK: Thank you. Good to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, tell me, how bad is this year's flu so far and why?

QUICK: Well it certainly is racking up a higher case count. There are two things that are different about this flu. One is that the mix of strains of flu that actually hit the US were different than what were predicted months ago when the vaccine was made. So, we're only getting at best a 30 percent success rate with the vaccine. The second thing is this is a particularly vicious strain of the H3N2, which -- it causes a reaction in the immune system such that you can get a really rapid and catastrophic death. It's the sort of characteristics of the virus that we had in the 1918 and the 2009.

CURWOOD: And when you talk about 1918, the so-called Spanish Flu, killed how many people?

QUICK: Between 50 and 100 million; more recently the estimates have been on the higher side.

CURWOOD: What is it about our typical flu response that isn't working in your view?

QUICK: Well, one of the big things is that the flu vaccine is one of the least consistent of the vaccines we have because it's made each year based on the best scientific guesses of what particular strains of flu will hit us. And if we're right we get 60 percent effectiveness at the best, and if we're wrong, we've gotten as little as 10 percent. We really need a much, much better flu vaccine.

CURWOOD: Now, you say that our collective flu complacency is actually what's killing us. What do you mean by that?

QUICK: Well, that what happens is when we have a bad flu season, there's this sort of panic and a lot of activity - how do we take care of ourselves, what about our children? - but then once that season goes and it's off the headlines - kids are back to school and businesses are going again - we fall into a complacency. We just get focused on other things.

CURWOOD: What's likely to be the economic impact of a rough flu season like we're having this year in America?

A U.S. marine receives the influenza vaccine. This year’s H3N2 flu virus, like the strain of the flu that proved so deadly in 1918, is highly contagious and killing numbers of young healthy people and children. (Photo: U.S. Pacific fleet, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

QUICK: Well, we know on average from work done by the Centers for Disease Control that the average flu hits the US economy at over $80 billion dollars a year of which about $10 billion are the health costs. So, this year we can expect that the total will go beyond that, when you consider lost time and all of the other factors.

CURWOOD: And how many people - I know this is kind of grim - but how many people do you think will perish in the course of this? Or are likely to?

QUICK: Well, the highest that we've seen is 56,000. I wouldn't be prepared at this point to predict, but that would be near the top end of what one might expect.

CURWOOD: 56,000 people! I mean that's more people than who die in car crashes every year!

QUICK: Yes, it is, and that's really unacceptable to be in a situation where we have a vaccine that really won't protect us, and when we see that kind of a death rate. And if we had what we had in 1918, which we could have again, which is a flu that is both highly deadly and highly contagious, we could be talking about multiples of that.

CURWOOD: So, what's the fix to the flu vaccine problem? You say at best it’s 60 percent effective.

QUICK: So, if you think of the flu virus as a mushroom, and the top of the mushroom is the part that is easiest to make the vaccine to, and that's what we've been doing, but that's the part to keep changing all the time. And the stem, which is the least changing and the most stable, that's what we really need to have a vaccine for. So, the universal flu vaccine is meant to either get a wide range of strains of flu or to get that stem so that we don't have to keep getting a flu shot every year, and so what we need to do is to move along, accelerate research on the universal flu vaccine. And Professor Osterholm from the University of Minnesota has said - and he said this five years ago - we need to put a billion dollars a year into getting a universal flu vaccine. Which is a fraction of what the influenza cost this country alone. If we get a good flu vaccine, universal flu vaccine, it would be good for the entire world.

CURWOOD: So, how does complacency figure into this really high death rate? I mean, this is the 21st century. You’d think that we would have had this handled by now.

QUICK: Yes, and here's the thing. We have the scientific know-how and the public health community knows what to do, but we need to... first of all, we need to invest in making sure that we have the best public health information in communities. The fact is that basic good public health, personal prevention is actually highly effective, more effective this year than the vaccine as it turns out.

CURWOOD: Well, and what are those public health things that people are doing that are so effective?

QUICK: Well, simple things. It's proper handwashing, not just sort of wet and dab, but a good 20 seconds, two verses of Happy Birthday, with good soap and all over. It really makes a difference. The second thing is safe sneezing and coughing. Covering your sneeze and cough, but not with your hands where you're going to wipe it on surfaces, but into your sleeve, and the third thing is stay home from work. Stay home whether it's work or school when you do have the flu and don't be macho about it. People at work or school won't appreciate that.

CURWOOD: One thing that's attracted people's attention this time is surprise at seeing young people, you know, 20-year-olds, 30-year-olds, because some people have the attitude the flu just sort of shuffles the nursing home population.

A health worker wore protective gear during the Ebola crisis that took hold in West Africa in 2014. (Photo: USAID, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

QUICK: One of the basic misconceptions is that if you're young and healthy, you don't need to worry about it. The problem is if you are somebody that’s susceptible to some of the complications of influenza, it doesn't matter how young you are, how healthy you are. If that flu virus stimulates this reaction in your body where your immune system starts fighting with itself, it doesn't matter how fit you are. And when that particular kind of a reaction happens, that's when we see young, otherwise healthy people die.

CURWOOD: So, how does someone know if their immune system can be thrown into a tailspin?

QUICK: Well, you don't. Now, we know the dynamic, it's actually got a name. It's called a Cytokine storm. You can call it a C storm. It's got a lot of research on it, but we still don't know how to predict it, we don't know how to guess who's it going to be. So, when you hear these stories of people who have seemingly had the flu and have been seen and diagnosed and go home, and then, you know, are dead, it's a very good likelihood that they're one that was susceptible to that, and that C storm got going and basically put them into a respiratory failure. And that's why it is so important to get the vaccine. It may only cut your chance by 30 percent, but it's important to get the flu vaccine, but also if you are in the category of young and old for which the pneumonia vaccine is appropriate, that actually helps in preventing the bacteria complication of influenza, which is the other thing that will kill people.

CURWOOD: Now, you were talking about the flu because we're looking at this right now, but you wrote your book to sound the alarm that we could have an amazingly deadly epidemic that could really knock us back in horrible ways. Just how horrible a scenario are you projecting?

QUICK: Well, the most likely worst-case scenario would be this version of the flu, a pandemic flu, as in 1918, highly deadly, highly contagious, that spread around the world and there's a scenario that Bill Gates has supported that’s looked at what would happen. And in 100 days, we'd have about three-quarters of a million deaths. That would be like a bad year for the seasonal flu worldwide, in 100 days, three-quarters of a million. In 200 days, 30 million people, and it would hit every major population center. So, you get a cascade. What happens with the flu, you got the disease, sends people into the hospitals, and when you have people going into the hospitals that are at a rate more than they're equipped for, then that can quickly pull the health system into a crisis. You then, in workplaces, have suppliers, staff, customers affected by this and in this just-in-time economy of just-in-time inventory then you break down that system and so on down the line. And so it's that chain reaction that a really devastating epidemic would catalyze.

Jonathan Quick’s new book, The End of Epidemics: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop It, is both a call to action to develop a universal flu and a plea for all countries to develop preparedness plans for containing the next major disease outbreak. (Photo: Courtesy of St. Martin’s Press)

CURWOOD: So, what's to be done? To explore that question Dr. Quick, I want to ask you about another epidemic, Ebola. What did we do wrong after the Ebola epidemic broke out in West Africa?

QUICK: Well, let's put that epidemic in perspective. There have been 22 previous Ebola outbreaks in Africa since Ebola was first discovered several decades before. And every one of those came to an end with only a few hundred cases and even fewer deaths. So, what was different in West Africa was two or three things. First of all, the received wisdom was that there wasn't any Ebola in West Africa. In fact, German researchers had found Ebola there back in the 80s, so they should have been aware that it was a possibility. And so, the first thing is West Africa didn't really have the information it needed to protect itself.

The second thing is those three countries there have all been through decades of civil unrest of one kind or another. So, the basic ability to detect and rapidly respond to an outbreak wasn't there. Once it started to become apparent to the people on the ground and specifically MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières), Doctors Without Borders, they started ringing the alarm. One of my heroes from Ebola is Dr. Joanne Liu, the president of MSF worldwide, and she started in March of 2014 trying to ring the bell and say, “Look you've got a problem here, this is not normal”. And actually it was only when two international workers from the US were expatriated to Emory Hospital in the beginning of August 2014, within four or five days, the World Health Organization called the global emergency. So, there was a lack of information and then there was delay in responding and that's what let it really get embedded.

CURWOOD: So, what do you make of the World Health Organization ignoring the Médecins Sans Frontières, Doctors Without Borders, when they were sounding the alarm when it was still in Africa?

QUICK: Well, I think it was a combination of factors, which WHO has recognized, that they really need a faster system and a system that is de-politicized. So, when you mix the decisions to whether or not to act in a political context, the trade people don't want you to announce that you've got an epidemic, the tourist people don't, and so you've got to put it on a scientific basis. And I think to the credit of WHO leadership, they've said, “You know, this didn't go the way it should have,” and they've instituted a much stronger system, much more scientifically based and much more transparent.

Jonathan Quick is senior fellow at Management Sciences for Health in Boston and an instructor of medicine in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School. (Photo: Courtesy of St. Martin’s Press)

CURWOOD: Now, to deal with these epidemics, you have a preparedness plan that you call the power of seven. Could you just please briefly describe those seven steps for us?

QUICK: Yes, the first is leadership that is courageous, decisive, and moves ahead, that will not dither or deny, but that really rises to the occasion and acts quickly. The second is we need to build the basic public health abilities that we've talked about to be able to prevent and quickly respond to. That's a platform. The third is focus on prevention – on good hygiene, on mosquito control. The fourth is to really understand communication. Social media, for example, is a double-edged sword. It spreads falsehoods and it also helps you understand how people are thinking about it. And number five is innovation. We need new vaccines, new diagnostics. We also need a even better early warning system. We've been able to reduce hurricane deaths 95 percent in the last 50 years with good early warnings. Number six is investments and our calculation is that if we put together the health systems part of it, the innovation part of it and the emergency response, that's about $1 per person per year, and finally everything that we've seen tells us that we will fall back into complacency unless we really have strong advocates and a mobilized and engaged citizenry in keeping the investments and the work happening between outbreaks.

CURWOOD: So, in your book, you raise a positive example of how in China they had trouble with SARS the first time around, but the second time around the outcome was much better. Tell me that story, please.

QUICK: So, just to put this in perspective, SARS, which appeared in China in 2003, was the first really new virus of pandemic potential in this century.

CURWOOD: And just for the record, in case people don't remember, SARS, of course, stands for Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome, if I recall correctly.

QUICK: Yes, indeed, and it can be rapidly fatal. So, it was totally unknown at the time that it hit. And there's this man who took it to Hong Kong on the ninth floor of the Metropole Hotel, and from there it spread to 27 different countries within a matter of weeks. WHO quickly reacted and those countries reacted. It was probably a plane ride away from getting into countries that didn't have the systems and we may still be living with this virus.

China in the first few months of it kept denying, and only when they were called to task by the WHO director general in public did they own up to it. This was a virus that had come from bats to a delicacy food called civets which is one common source of these epidemics, this so-called bush meat. So, China mobilized and really got vigorous in doing the inspections and setting up some rules and put in strict controls, and they have now dealt with outbreak after outbreak of influenza, dangerous influenza, in their poultry and all, by using the same control techniques and all that they developed with SARS.

CURWOOD: Dr. Quick, what's the single most important thing you want your readers to walk away with after reading your book or listening to our discussion?

QUICK: That the threat of major epidemics and pandemics is real. The scientific and public health community know what to do, but we're not moving fast enough with enough leadership and enough resources to protect us.

CURWOOD: Dr. Jonathan Quick, Harvard Medical School. Thank you so much for taking the time today.

QUICK: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- TIME: “Our Complacency About the Flu is Killing Us” by Jonathan Quick

- The Wall Street Journal: “An Action Plan for Averting the Next Flu Pandemic” by Jonathan Quick

- Management Science for Health

[MUSIC: Dan Sullivan Trio, “Corcovado” on Night and Day, composed by A.Jobim, DanSullivanTrio.com]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Hannah Loss, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Aynsley O’Neill, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth