More Pipelines, Fewer Salamanders

Air Date: Week of February 16, 2018

The Eastern Hellbender is the largest salamander in North America, reaching lengths of up to 24 inches. It’s also the official amphibian of Pennsylvania. (Photo: Dave Herasimtschuk / Freshwaters Illustrated)

Large-scale natural gas pipelines often have environmental impacts, but so can smaller ones. In Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia thousands of small pipelines are being built to link fracking wells to the energy infrastructure. As the Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports, their construction is linked to muddier streams and the sharp decline in populations of the Eastern Hellbender salamander.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Pipelines that can carry huge amounts of oil and gas over hundreds of miles get a lot of coverage in the news media, but small ones get scant attention, even though their sheer numbers make for a major impact. In Pennsylvania and Ohio, the construction of thousands of minor pipelines to connect fracking well pads to the larger distribution system could be driving a little known amphibian to extinction. The Allegheny Front's Julie Grant has our story.

[SCHOOL CHILDEN CHATTING AND LAUGHING]

GRANT: High school students file into Nicole Costello’s small reptiles class at the Penta Career Center in Toledo, Ohio.

COSTELLO: Alright, welcome welcome to this lovely Tuesday. Did everybody sign in?...

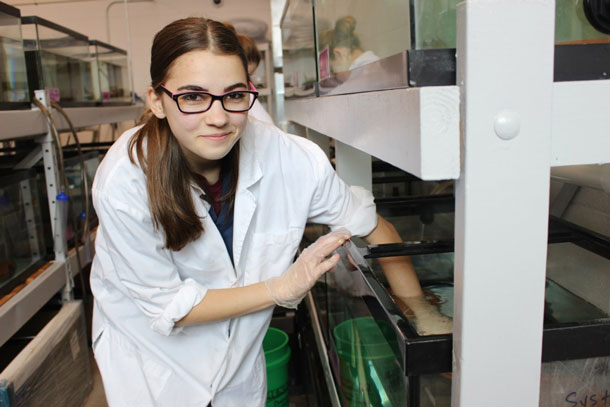

GRANT: They’re learning firsthand how to foster an aquatic species that experts say is in decline - the Eastern Hellbender Salamander. In a bio-secured room on campus, 18 year old Theresa Paff and other students clean the glass tanks, weigh and cut up worms to feed to the young Hellbenders they’re raising. Paff picks up one that’s 3 year old.

18-year-old Theresa Paff cares for Eastern Hellbender salamanders at the Penta Career Center in Toledo, Ohio. (Photo: Julie Grant)

PAFF: It’s really hard to hold. They always like to move, and they’re so slimy and slippery.

GRANT: These are not the cute, colorful little salamanders that might come to mind. They’re brown and mottled.

LIPPS: Some people would say they’re so ugly they’re cute.

GRANT: Greg Lipps is an expert on Hellbenders at Ohio State University, and works with the high school program. He says there’s good reason they’re often called snot otters, Allegheny alligators, or old lasagne sides.

LIPPS: They’re kind of a flattened, wrinkly sided, beady eyed salamander. Everything about them is made to live underneath a big rock in tight spots and darkness.

GRANT: Lipps says the adults can get big - over two feet long, and can live 35 years or more. They’re mainly found in streams along the Appalachian Mountains in Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. And these guys are tough, the species has survived for millions of years - which is why Lipps was so concerned when he and a colleague found an 82-percent drop in their populations in Ohio… they just weren’t finding many young Hellbenders.

LIPPS: It’s kind of like if the whole world became a nursing home overnight. You know that the end is near if you don’t have any youngsters in these populations.

GRANT: Researchers suspect the problem has to do with increased sediment in the water. Young hellbenders are thought to live in little spaces in gravel beds, that are easily filled with sediment. Lipps has watched as waterways, especially in the steep hills of eastern Ohio, near the Pennsylvania and West Virginia borders, have gotten muddier.

The reason seems obvious to him: pipelines.

LIPPS: And you can trace this, it’s not rocket science when you see the muddy water to drive upstream until you see clear water and then figure out well, what’s happening, where’s the in between? And when I’ve done that it’s been pipeline construction.”

(SOUND OF PLANE ENGINE FIRING UP)

GRANT: To get a better picture of the gas pipeline boom here, Ted Auch of Fractracker, a non-profit that tracks the fracking industry, has organized a tour by plane of West Virginia and Ohio.

(SOUND INSIDE PLANE)

GRANT: As we get into the air, he’s floored by how many hillsides are cleared of trees, to make way for pipelines.

AUCH: Look at this one, Julie, look how zig and zagging this puppy is...”

A pipeline crossing Captina Creek. (Photo: Liza Butler)

GRANT: You can see these gathering lines connecting every well pad and compressor station. Ohio and Pennsylvania are among the states with the most gathering lines in the country - each with more than 20-thousand miles of them. Pipeline companies are supposed to replant the pipeline corridors. But Auch says many don’t.

AUCH: See, Julie, that’s all pipelines. And they have not hydro-seeded that, you see what I’m talking about? And they’ve got that apron, that tarping material that’s supposed to prevent the loading of sediment down. But they didn’t hydroseed any of that.

GRANT: On the ground in eastern Ohio, the hills are alive with pipeline construction. To the north, are the bigger transmission lines - the Mariner East and the Rover. Smaller gathering lines have names like the Hot Sauce Hustle, and Dr. Awkward. Ohio State researcher Greg Lipps says when companies strip these steep hillsides of forest for pipelines, it can destroy his team’s efforts to restore stream banks, and protect the habitat for Eastern Hellbenders and other aquatic species.

LIPPS: What you create is effectively what can be a river of mud every time it rains. It’s really a problem. And the amount of silt and sediment that can come from a pipeline cut and from an eroding stream bank is immense.

(WATER SOUNDS, BIRDS BY CREEK)

GRANT: Many of the new pipelines also cross the streams, themselves. Like here in Captina Creek, a high-quality stream and home to Hellbenders. It empties into the Ohio River. The pipeline companies either bore underneath the stream bed or dig right through the water. According to an Allegheny Front review of applications to the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, the state has issued at least 13 permits, including 66 pipeline stream crossings in the Captina Creek watershed alone since 2014.

Harry Kallipolitis manages the Ohio EPA’s permitting process. His agency, like regulators in here Pennsylvania, is required by the Clean Water Act to certify that pipeline crossings are not going to jeopardize stream quality.

KALLIPOLITIS: We evaluate what benefits to society it may have and weight that against the potential impacts to water quality. Our lower bar is not jeopardizing the existing use or how that stream is performing. And we do authorize the potential lowering of water quality with potential mitigation to make up for that loss.

MarkWest cryogenic and fractionation plant that processes natural gas in Wetzel County, WV. (Photo: Renee Rosensteel)

GRANT: Kallipolitis says there’s no regulation looking at the cumulative impacts of the new lines. But he says they have not seen impacts on any streams from multiple pipeline crossings.

KALLIPOLITIS: We evaluate a lot of streams in Ohio, and you know to my knowledge we haven’t had any of those reports come back to us and say that the stream is jeopardized by multiple crossings associated with pipeline projects.

GRANT: Still, Kallipolitis says the Ohio EPA will propose new sediment regulations for pipelines in the coming months. And researchers at West Virginia University are starting to look at ways to reduce the environmental impacts of pipelines. Michael Strager is a professor of resource economics. In a study that just got funded, he plans to use GIS technology and drones to map pipelines in the region, and then his colleague will match the locations with water quality data in nearby streams.

KALLIPOLITIS: So I think how our work is going to be useful is to really aid in the permitting process as part of a planning approach to really direct this industry to places where we can potentially have less of an impact than others.

GRANT: Like the students at Penta Career Center, these West Virginia researchers want the waterways clean enough so species like the Eastern Hellbenders can survive here. The high schoolers will join experts, and release the young salamanders into the streams of eastern Ohio over the summer. I’m Julie Grant.

CURWOOD: Julie Grant reports for the Pennsylvania public radio project, the Allegheny Front.

Links

Allegheny Front: “Are Pipelines to Blame for Decline in Ancient Salamanders?”

How to protect and conserve the Eastern Hellbender

The American Petroleum Institute’s Natural Gas Industry Impact Report

Ohio EPA’s water quality study of the Captina Creek watershed

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth