December 20, 2013

Air Date: December 20, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Capitol Hill Bid For Bicycle Safety

View the page for this story

Cyclists and pedestrians account for nearly 16 percent of all highway deaths yet receive just 1 percent of safety related funding. The founder of the Congressional Bike Caucus, Oregon Democrat Earl Blumenauer, tells host Steve Curwood that a new Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Act he introduced to Congress could change the priorities. (10:50)

Power Shift-Winter Bike Share

View the page for this story

In winter's ice and snow, biking might seem like a bad idea but as Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports that Cambridge Massachusetts is joining a number of cold cities across the country that are opting to keep their public bike-share programs rolling year round. (06:40)

Inheriting Fear

View the page for this story

Moshe Szyf of McGill University tells host Steve Curwood about new research demonstrating that fear can be passed on from one generation of laboratory animals to the next. Epigenetic changes are most likely responsible, and this provocative study is bringing new challenges to how scientists think about behavior and evolutionary change. (09:55)

Beyond the Headlines

View the page for this story

Peter Dykstra, publisher of the Daily Climate and Environmental Health News, tells host Steve Curwood about a bizarre (and perhaps satirical) article from China detailing the silver linings to the country's serious smog problem. Also a look back at the life of Chico Mendes, and a look ahead at the arrival of outspoken Keystone XL critic John Podesta as a presidential counselor. (04:50)

Backyard Bees in Atlanta

View the page for this story

Eco-activist Laura Turner Seydel tells host Steve Curwood that she did everything she could to make her yard a haven for her beehive but she couldn’t protect the bees from the deadly chemicals her neighbors used on their lawns. (05:10)

Living Walls

View the page for this story

Energy efficient fuels and insulation are the usual climate-friendly ways to heat and cool our buildings. But as Laurie Howell reports from the IEEE (eye-triple-E) Spectrum series Becoming Bionic, some engineers are mimicking human skin to create better climate control. (09:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Earl Blumenauer, Moshe Szyf, Laura Turner Seydel

Reporter: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra, Laurie Howell

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Americans are falling out of love with the automobile and taking up bicycles - and one result is more bicycle accidents.

BLUMENAUER: Part of it is we have not yet trained drivers to be careful before they get out of a car so they don't door somebody; part of the problem is that we have not invested as much as we should in facilities to make cycling safer.

CURWOOD: But many cyclists ignore the rules of the road. Still, bike friendly cities are increasingly popular.

SEIDERMAN: A city that’s very bikeable and walkable is more livable. There’s fewer vehicles from an environmental perspective and there’s that whole feeling of what a city feels like when there’s people about as opposed to just cars.

CURWOOD: And Chinese satire - perhaps - about why their pollution might be a good thing. We'll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm. Makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

Capitol Hill Bid For Bicycle Safety

Citi Bike in New York City is the largest bike share program in the United States. (Bitstock photo)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. For years in America, the car has been king. As General Motors once put it, “it’s not just your car, it’s your freedom.” But increasingly Americans are finding a new kind of freedom, the freedom from traffic jams and lack of exercise that can be found behind the handlebars of a bicycle. So as driving mileage has dropped by more than eight percent in the past decade, at the same time the proportion of people commuting to work by bike has increased in 85 of 100 of America's largest cities. One of those two-wheel commuters is Oregon Democrat Earl Blumenauer, the founder of the Congressional bike caucus. The Representative recently introduced the Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Act, legislation that he says America badly needs.

BLUMENAUER: We have an imbalance in federal transportation policies, where a disproportionate number of the injuries occur to pedestrians and cyclists, but they receive a very small portion of the overall resources that should make our transportation safer. So what we’re working on here is to have the Department of Transportation track fatalities, injuries by mode. Everybody, almost without exception is a pedestrian at some point in their journey, and you noted that we’ve just seen an explosion in cycling interest around the country, and we need to make sure that we’re doing all we can to make sure that experience is as safe as possible.

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about the safety record for bikes on our roadways. What are they like these days?

BLUMENAUER: Well, what we’ve seen in communities like mine, in Portland, Oregon, where we have had a dramatic increase in bicycle use, well over 400 percent, the accident rate is going down, but the number of accidents are going up. There’s still too many. Part of it is we’ve got cyclists who don’t obey the rules of the road, which drives many motorists crazy and, frankly, just gives me apoplexy. Part of it is we have not yet trained drivers to be careful before they get out of a car so they don’t door somebody; part of the problem is that we have not invested as much as we should in facilities to make cycling safer, separated bike lanes, signals that are geared for cyclists.

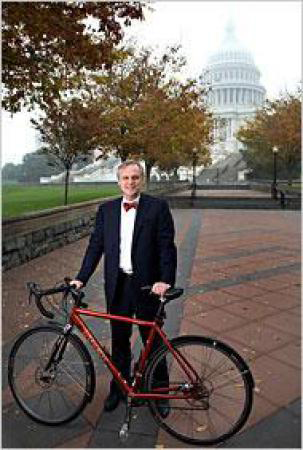

Congressman Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) commutes to work by bike (Earl Blumenauer)

CURWOOD: Now what about the attitude of automobile and truck drivers on the road. I use bikesharing in the Boston area to do the last couple of miles of my commute. I often take the Amtrak to get into the city. And, you know, frankly, some drivers seem outright hostile to bikes coming by.

BLUMENAUER: I think that’s true. As I mentioned a moment ago, it’s important for the cycling community that they be respectful of motorists and they don’t do things - running red lights or being reckless - I think that’s important. Although I’ve had limited experience actually driving in Boston over the years, when I have, I have found there are cranky drivers that I encounter when I am a motorist. So I think that it’s not unique to the car-cycle dynamic. Part of this challenge is to help people understand that the cyclist is the friend of the person driving a car.

CURWOOD: How’s that?

BLUMENAUER: Every person that’s in a bike lane next to you is not in a car in front of you. They’re not competing for a parking space at the ultimate destination. They’re not polluting the air because they’re burning calories instead of fossil fuel. We’ve not done a very good job of helping people understand how the promotion of cycling is the quickest and cheapest way to get more highway capacity.

CURWOOD: Congressman, you are famously the founder of the Congressional bike caucus. Tell me about the goals of your caucus, and tell me about some of the other members.

BLUMENAUER: The goal of the Congressional bike caucus was to help bring people together around issues of cycling in an era of partisan divide, the bike caucus is “bike-partisan.” It’s been Republicans and Democrats together. A Republican Congress member from Florida, Vern Buchanan, was telling me his cycling this year, he’s lost 35 pounds. He knew to the nearest mile how far he’d gone, and it was several thousand miles this year, and that he was just absolutely committed to supporting better bike facilities in his district in Florida and around the country.

There’s Congressman Mike Doyle from the Pittsburgh area, who determined that when he turned 60, he was going to celebrate it by going on a bike ride of over 100 miles, and he trained. He too lost 30 or 40 pounds, he raised thousands of dollars for charity, it was really quite a testimonial. So Republicans, Democrats; for me it’s been an island of agreement, and positive stories in a climate that too often is negative and partisan.

CURWOOD: And how big is the Congressional bike caucus?

BLUMENAUER: At one point we had over 230 members, a majority of Congress.

CURWOOD: Congressman, to what extent is there any kind of anti-biking caucus on Capitol Hill or other members who think that biking is really a silly thing to care about.

BLUMENAUER: Well, several years ago there was a reaction from some people in Republican leadership, cutting some ads about cycling being a stupid response to the energy crisis. Actually one incumbent Republican who cut a re-election ad against a challenger - this is a gentleman in Pennsylvania - saying what was her answer, ride a bike? And she actually had a response at a press conference to which she rode a bike, and she said, absolutely this is one of the simple common sense things we can do to make people feel better and that doesn’t add to congestion and pollution and it stretches our energy resources.

There was another person who literally came to the floor mocking our work on cycling, and I will say it invoked a pretty ferocious response. Cyclists are getting much more involved politically, and there were thousands of dollars spent against this guy who decided to poke fun and ridicule cycling, and he subsequently joined the bike caucus, I will say, and the woman who rode her bike to the press conference responding to the negative ad about cycling ended up winning.

CURWOOD: What’s your commute like in Washington ?

BLUMENAUER: Well, my commute in Washington is only about a mile. For 17 years, I’ve used a bicycle as my primary way of getting around, zipping up to speak at a conference, or to a meeting at the White House. I’ve been able to burn hundreds of thousands of calories, I’ve never been stuck in traffic and I always find a place to park.

CURWOOD: What’s the bike rack like at the White House, by the way?

BLUMENAUER:[LAUGHS] The first time I did it, I actually had to talk my way onto the White House grounds. Ironically, I had been invited by Vice President Gore, to come up and talk about some environmental things, and I biked in and the Secret Service was just kind of like, “Hmmm, we don’t think so.” Ultimately it was just, “well, what if I had driven a car?” “Well, we’d open the gate and you’d come in.” I said, “Well, pretend it’s a car,” “OK, but just lean it up against the front of the White House.” I haven’t had those problems of late. There is just more and more interest in Washington, DC, generally over how much cycling has added to the vitality of the Washington, DC, comeback.

Congressman Blumenauer (left) with members of the Congressional Bike Caucus. (Emanuel Cleaver)

CURWOOD: What do you see as the overall trend of biking in the United States now?

BLUMENAUER: The overall trend is one of dramatic growth. In city after city, the bike commute is increasing 10 and 20 percent a year. Bicycle sharing is an interesting metaphor that has just captured the imagination of not just urban transportation officials, but the city planners around the world. There are over 650 bike sharing systems worldwide.

CURWOOD: You said, a metaphor. What do you mean, a metaphor?

BLUMENAUER: Well, a bicycle is the indicator species of a livable community. This is a community that is human scale, that is, where people are safe. It’s welcoming. From my vantage point, this is a symbol of what we need to be doing with policy generally in your nation’s capital. It’s a very powerful tool and a representation of how far we’ve come.

CURWOOD: So let’s cut to the chase here. How much money is Congress willing to appropriate and authorize for biking?

BLUMENAUER: We don’t know yet. Part of the problem is we’re just having a collapse of the Highway Trust Fund. We are in a very serious way approaching the October 1 deadline where if something doesn’t happen, there will be no transportation construction money for new projects, whether they are freeways, light rail or bike paths. We have not raised the gas tax in 20 years, so we’re in a world of hurt. The key for us in Congress is to be able to face up to the fact that the Highway Trust Fund needs to be replenished, I would argue the gas tax increased for the first time in 20 years. If we don’t deal with the funding crisis, it doesn’t make a difference what your mode is, it’s going to be in trouble.

Oregon Congressman Earl Blumenauer (Earl Blumenauer)

CURWOOD: Earl Blumenauer is a member of the US House from Oregon and founder of the Congressional bike caucus. Congressman, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

BLUMENAUER: It's always a pleasure, I look forward to our next conversation.

Related links:

- bike, Blumenauer, bike caucus, bike share, bike safety, congress

- Rep. Blumenauer’s remarks when he introduced the bill.

- More about US Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-OR)

[MUSIC: Huey Piano Smith “Twas The Night Before Christmas” from Twas The Night Before Christmas (Westside Records 1998)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...startling evidence from the world of science that shows fears can be inherited from one generation to the next. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson: Pass Out” from Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson/Otis Spann: Bosses Of The Blues Vol 11 (RCA Bluebird Records 1990]

Power Shift-Winter Bike Share

Hubway bikes are sturdy and ready to ride all winter in Cambridge. (Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. And now, another in our series Power Shift, about the transition to low carbon energy in the Bay State.

[POWER SHIFT THEME]

CURWOOD: There are few things more energy efficient than generating your own transportation by pedal power. Still, as the snow and ice and dark of winter descend upon us here in the north, bicycling might seem unwise, and frankly, unappealing. But increasingly bike share programs in cold cities including Toronto, Denver, and New York are staying open through all four seasons.

Even when there’s snow or ice, some year-round riders say the roads are often clearer than the sidewalks.The Hubway bike-sharing system in the Boston area shuts down completely for the winter come Thanksgiving, except this year. The Cambridge part of Hubway is getting a winter try-out. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb has the story.

[TRAFFIC ON STREET]

BASCOMB: It’s a cold, overcast day but bike commuters in Cambridge don’t seem to mind. Some are dressed for the weather in heavy winter coats and thick mittens. Others wear sleek spandex and reflective orange jackets. At least a dozen bikers are stopped at a traffic light in Inman Square. A student, Mitali, dressed in a warm hat and long black jacket heads for the rack of Hubway bikes. She uses a key fob the size and shape of a thumb drive to unlock one.

[BEEPING OF HUBWAY LOCK, RELEASE OF BIKE FROM THE RACK]

MITALI: I love it, I think there are so many students especially that use the bikes to get to school.

BASCOMB: She finds biking easier than relying on public transit.

MITALI: I do take the bus in the evening, if it’s too late at night and I don’t feel like biking. But a lot of the buses are only every other hour so you have to wait a long time. Then I feel like I might as well just bike. I’m wearing all these layers anyway.

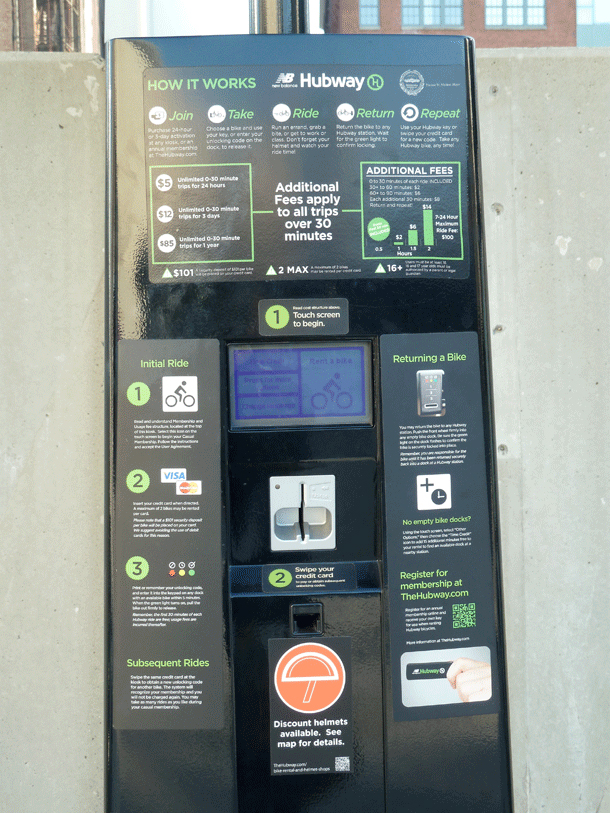

(Hubway)

BASCOMB: It’s that kind of convenience that’s made Boston’s public bike-share program so popular. Roughly 9,500 people paid the $85 annual membership fee that allows them to ride bikes from any of the 129 stations located across greater Boston. But from now until March the 27 locations in Cambridge will be the only ones open.

Roughly 9 percent of people in Cambridge commute to work by bike, that’s the fifth highest in the country. So Cambridge is an ideal location for a pilot program to demonstrate how a winter bike-share program could work out in snowy New England. Charlie Sulk is a big fan.

SULK: I support the extension of the season. I really wish they had brought it out to Boston as well.

BASCOMB: Sulk is a student at MIT, and he plans to use the bikes as much as possible over the winter.

SULK: Right now I’m experimenting with ways I can still use the bikes, but for the most part I’m not going to be using it nearly as much as I was before because it’s just in Cambridge and I tend to travel between Boston and Cambridge a lot.

BASCOMB: (on tape) Do you think you’ll still want to ride the bike when there’s eight inches of snow and slush on the ground?

SULK: Yeah, for sure. The ironic thing is when the bikes go away I tend to use my skateboard more often because that’s my next go-to mode of transportation, so if I can get around on my skateboard I’m sure the bike should be no problem.

BASCOMB: And Cambridge officials want to be sure that neither snow nor rain will keep Hubway bikers from swiftly completing their journeys.

SEIDERMAN: The Hubway is really meant to be a transit system, a transportation system, for people to be able to use and that means that it really should be accessible all the time.

Day users can swipe their credit card and for five dollars have access to a bike for 24 hours. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Cara Seiderman is the transportation program manager for the city of Cambridge. She says Cambridge is particularly well suited for this winter pilot program.

SEIDERMAN: It made sense to pilot it in Cambridge because we have a bit easier time. All of our stations except for one are offstreet so they’re not going to be dealing with snow plows. Those are things that we’ll have to really think about in the future if it did get expanded in the entire system. But it was an easier decision because that obstacle, that challenge, was not in place.

BASCOMB: But when the snow does come Seiderman say they have a plan for dealing with it.

SEIDERMAN: The company that runs Hubway for us, Alta Bike-Share, is under contract and they will be responsible for clearing the stations of the snow and managing the bikes going in and out. There is also a way to electronically shut down the system so that you can’t take a bike out remotely. This has actually been done a couple times, like last year when Hurricane Sandy was approaching, the system was shut down in advance.

BASCOMB: Hubway bikes first started rolling around the Boston area in 2011. Since then it’s grown to serve some 90,000 casual users each year in addition to the annual members. The Boston system was modeled after Montreal’s bike share program, which operates in spring, summer, and fall.

SEIDERMAN: Now systems that are going into place including New York and Chicago, big cities with serious winters, are assuming that they’re going to be a year-round system.

BASCOMB: Cities like Copenhagen, Denmark and Helsinki in Finland already have year-round bike-share programs. And despite the cold they are very popular. Of course, a winter bike-share system comes with additional costs for maintenance and snow removal. At the same time revenue goes down because fewer people choose to ride. But Seiderman says it’s still worth it.

SEIDERMAN: In general, a city that’s more bikeable and walkable is more livable. There’s fewer vehicles from an environmental perspective and there’s that whole feeling of what a city feels like when there’s people about as opposed to just cars and it’s the kind of city that we want to see.

BASCOMB: Officials estimate that in a busy month of riding Hubway bikers offset 100,000 pounds of carbon dioxide and burn more than 6.6 million calories. Last year Hubway surveys asked riders what they would most like to change about the system. Seiderman says overwhelmingly the response was to extend the program year-round.

SEIDERMAN: [LAUGHS] I would say that this is apparently one of the most popular things the city has ever done based on the feedback that I’ve gotten. People legitimately call up the city or send us communication when they have a complaint about something but less often do we get the kudos but I have gotten more feedback about the Hubway being open year-round than since anything than since Hubway itself opened.

BASCOMB: The Cambridge pilot program is just getting started and surrounding cities are watching closely to see how winter biking works out here. If all goes well, next year Hubway riders might be able to peddle year-round through all of greater Boston.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- Institute for Transportation and Development Policy Report on Bike Shares

- Hubway

- City of Cambridge on winter Hubway

[MUSIC: The Waitresses “Christmas Wrapping” from Ze Christmas Album (Ze Records 2004)]

Inheriting Fear

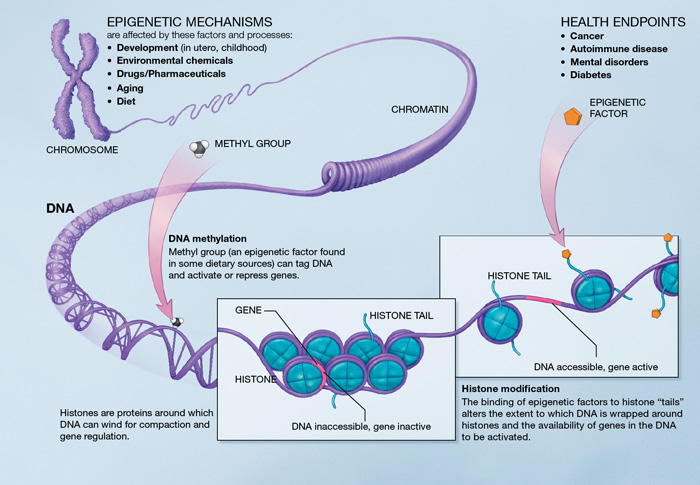

This diagram shows the method by which epigenetics works. (Wikipedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Whenever we welcome a new baby into a family, someone's bound to say, "Look, he has his father's eyes," or "She has her mother's hair." For most of us, that's how we understand inheritance, that we get particular physical characteristics from our parents. But new research recently published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, based on lab animal research, has found that direct experiences and fear could be transmitted down through generations. We turn now to Moshe Szyf, a professor at McGill University in Montreal, to learn how the experiment worked.

SZYF: What the researchers did was to expose a mouse to a smell, and at the same time, shock the mouse with a mild electrode shock. So now the mouse associates the smell with the shock, and whenever the mouse will smell that smell, then the mouse will startle because the smell reminds the mouse of the shock. This is a known property of animals, they recognize smell that protects them from fearful experiences, for example, mice and rats are afraid of fox urine, and that makes sense because a fox is a predator of a mouse, and this way the mouse can recognize when there’s a fox around and survive.

CURWOOD: So how did they transmit this to their offspring?

SZYF: So usually this is selected probably by natural selection. Animals that acquire mutations during their evolutionary lifetime that protect them and allow them to survive against their predators, probably that’s how mice recognize fox urine. But in this case, this was not going through natural selection because the mouse passed it directly to its offspring, through the sperm.

CURWOOD: So the offspring...this worked in the first generation as well as the next...

White mouse (Bigstockphoto.com)

SZYF: The second. I think it went up to two generations.

CURWOOD: So if we were talking in human terms, you’re talking not just a child, but a grandchild.

SZYF: A grandchild who will remember an experience like this. Yes.

CURWOOD: How is this possible? How could the children and grandchildren of the original mouse fear something that they never experience themselves?

SZYF: We don’t know how this could happen. I mean, I still...you know, it sounds like science fiction. This idea that experience can direct the phenotype of the next generations, is very problematic and controversial because we don’t have a clear mechanism, however, what is coming up in the last decade, that it’s possible there is a epigenetic mechanism that allows this to happen, that is, the experience changes the epigenetic state of the sperm, and I’ll explain immediately what’s epigenetic, and that sperm is now marked, and can pass this mark to future generations.

CURWOOD: Yes, I’m ready to hear the explanation of what exactly is epigenetics and how that works.

SZYF: So epigenetics is the additional information on genes. So we inherit from our parents the genes, and they are inherited in a very accurate way from generation to generation, and up until now we thought that only those genes are inherited from generation to generation, and therefore there was no way an experience could be inherited from generation to generation. But now we know that genes are programmed, and that programming involves marking of the genes by chemicals, and also packaging the genes in chemical material. And that will define if a gene works or not. So, for example, if the experience managed to change the way a particular gene is marked in the sperm, that mark could be passed to the next generation, and indeed, what the authors have shown is that a chemical mark on the gene that codes for the receptor of this specific smell was changed in this way, and that was probably passed to the next generation.

CURWOOD: But what evidence do we have that epigenetics works from one generation to the next?

SZYF: The evidence is still sparse, but there is accumulating evidence. There are epidemiological studies from humans that show that experiences could be transmitted across generations, and the most famous one is the Dutch famine of 1944, and these are Dutch who were exposed to very low calories, punished by the Germans, and we see now phenotypes in their grandchildren, metabolic phenotypes, and there is a suspicion that that was an epigenetic transmission of the experience of famine. You know, the famine during the pregnancy of their grandmother kind of adapted them to a lifetime of famine, right? And in a life of lack of food, you better binge on every food you find, and turn it into fat. But what happens when the grandchildren are born into a rich Dutch society? That preparation by the experience becomes maladaptive.

Moshe Szyf is a professor in the department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at McGill University. (McGill University)

In animals there is evidence that certain exposure of chemicals, like Skinner’s work, could be passed four or five generations. And in that case it was pesticides, then there is evidence about depression and aggression. So there is evidence that experiences could be passed from generation to generation, and exposures could be passed from generation to generation. But what’s unique about this paper is that it points to a specific gene, a specific receptor, and a specific smell. This idea of smell-fear is so fundamental in evolution because it is something that is required for animals to protect themselves from their prey, and it was always believed that the way that is generated is through natural selection. This is the first time we have an epigenetic mechanism for that.

CURWOOD: So first time that instead of being hard-wired this a the function of one’s parents or grandparents’ experience.

SZYF: Right.

CURWOOD: What do you suppose is the role of epigenetics in evolution? I mean, it would seem that the fear response that was found in mice is evolutionary adaptation, but is expressed far more quickly than we typically think evolution could do.

SZYF: Absolutely. The classic evolutionary theory is basically what we call natural selection, which is there are random slow-changing genes that are selected by environment, and those few individuals that are selected would eventually form founders of the next generation of animals and all the others will disappear, and that’s how natural selection works. That’s a very slow process, and epigenetics introduces a whole new speed to that process because in difference from natural selection, which is random, this process is directed. If indeed epigenetics works in evolution, it will change all our calculations and the whole way we look at the way species originated and the way species evolve.

CURWOOD: So, what about those things that we just usually call “instinct”, and what I’m thinking of now is the generational migration of Monarch butterflies, right? It’s the fourth generation of Monarchs. They migrate thousands of miles from the north back to Mexico to the exact same tree where their great-grandparents started the migration months before to a place where they’ve never been to themselves.

SZYF: Right.

CURWOOD: No one really seems to know how they do that. I’m just wondering if epigenetics could be an explanation.

SZYF: Epigenetics could be a very interesting way of explaining that, and, in my opinion, probably the only way. I don’t know about anybody that has actually demonstrated that there an epigenetic change in these butterflies, but epigenetics might play a big role in those transgenerational experiences that are so dominant in the animal world.

CURWOOD: This research really raises a lot of questions, of course, about people and acquired behavior. I mean, what about people born and raised in cities with a lot of crime and violence. Does this study indicate that they might be more prone to living a life of involving crime and violence? Is there--are we talking about learned behaviors or would epigenetics be a factor?

SZYF: Being born in an aggressive environment causes changes by itself, and so you can pass from generation to generation aggression just by the behavior. So if the father is aggressive, and the child is born into an aggressive family, the child will become aggressive and so you don’t need sperm to transmit that, you can transmit it through behavior. But epigenetics could be a factor and if part of it is indeed transmitted through the generational line, it makes it harder to solve, right, because if it’s behavioral, if we change the environment, we can change that. But if it was already transmitted in the sperm, how can you change that?

CURWOOD: What could be the dark side to this? I mean, you talked about depression going down generational lines, aggression going down generational lines.

SZYF: I think the dark side is that, to a certain extent, you’re a consequence of the sins of your father, but there is an optimistic side to epigenetics. Genetics is final. Once you change the sequence, it’s impossible to change it back, whereas epigenetics is reversible. So if experience could create epigenetic marks, there should be experience that could remove epigenetic marks, and therefore, there might be a way that, even if you inherited dreadful experiences from your past generations, that a different experience will be able to remove it, and that might guide a lot of our behavioral studies and research in the next decade.

CURWOOD: Moshe Szyf is a Professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at McGill University. Professor Szyf, thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

SZYF: Thank you.

Related link:

Journal Nature Neuroscience

[MUSIC: David Byrne – Brian Eno “Feel My Stuff” from Everything That Happens Will Happen (Telemundo Records 2008)]

Beyond the Headlines

Pollution in China is so bad that pilots need special training on how to land in the smog (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

DYKSTRA: And now for some stories from beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra, who publishes the Daily Climate.org and Environmental Health News.

CURWOOD: Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, what’s beyond the headlines this week?

DYKSTRA: Steve, we’re going to start you out in that nest of naysaying, that den of dysfunction - our nation’s capital, Washington, DC. And Jon Podesta has a new job there. Jon’s a Washington heavyweight, he was President Clinton’s last White House chief of staff. For the past decade, he’s run a think tank called the Center for American Progress. Jon Podesta’s going to be a special advisor to President Obama, and his portfolio will focus on energy and environment, and that’s something he did a lot for President Clinton.

CURWOOD: So I imagine environmental advocates are doing a happy dance, and maybe some folks in industry aren’t so pleased.

DYKSTRA: Well, you know what, I’ve seen very little public reaction on the industry side, but green groups, yes, absolutely they’re pleased. There’s also one big question mark with all this that I see. He’s been very publicly critical for the past few years of the Keystone XL pipeline project. So critical that he’s going to sit out on any discussions in the White House about Keystone. So you’ve got one of the highest profile environmental issues the White House has now; you have a guy coming in with strong opinions, and because he has strong opinions, he’s not going to make his opinions known. To me that’s like Jon Podesta coming in and saying he’ll be a vegetarian except for the bacon and the lamb chops and the cheeseburgers. So we’re going to have to see how that works.

CURWOOD: But would he come back to the White House if he weren’t given assurances that Keystone isn’t going to have to happen on his watch?

DYKSTRA: You bring up a very good point. Presidents obviously worry about their legacy, key assistants to presidents also worry about their legacy, and Jon Podesta’s really staked out, a very, very strong environmental stand. As an opponent of Keystone I doubt he’d want to come back and on this watch as soon as he gets there have something he feels so strongly about go in the opposite direction.

CURWOOD: Now, I understand that you’ve dug up - well, I guess kind of an odd sounding story from China.

DYKSTRA: It’s so odd, in fact, that it sounds a little tongue-in-cheek, and it concerns all of the bad news you’ve heard for years from China about the growing pollution problems there. This week, the city of Shanghai set all-time records for air pollution. There’s another story that said that Chinese pilots that fly into the international airport in Beijing are going to have to receive special smog landing training just to be able to land a plane there on some of the worst days. CCTV, China Central Television, this massive government-run broadcaster, had another story this past week on its website. It made people so angry that it was pulled down from the website almost immediately. It listed five reasons why China’s massive pollution problem might actually be a good thing.

CURWOOD: Ummmm. Five reasons why China’s massive pollution might actually be a good thing? Such as what, Peter?

DYKSTRA: OK. Get pencils and paper ready. Here are your five reasons why pollution is a good thing for China, according to the story.

- It unifies the Chinese people ,

- Smog makes them more equal,

- It raises citizen awareness,

- It inspires plenty of pollution jokes,

- It inspires people to be more knowledgable about the science of what’s polluting them.

...at least that’s what the web piece on CCTV said.

CURWOOD: Well, are you sure this wasn’t supposed to be satire? Maybe some clever writer slid it past a sleeping censor?

DYKSTRA: Well, if you know anything about CCTV, it’s not exactly a hotbed of snark, it’s never going to be confused for The Onion. It might have been a satire, it might have been a serious attempt to put lipstick on a pig and make this awful pollution problem look good. Either way, it’s a statement on how bad things have gotten in China.

CURWOOD: OK. Before you go, Peter. Tell us what you have for us on the calendar.

DYKSTRA: Sometimes, we get to end these on an upbeat note, and sometimes we just have to put that aside and end on an important note. It was 25 years ago this week that Chico Mendes was murdered.

Chico Mendes was a rubber tapper who fought against deforestation in the Amazon before plantation owners murdered him 25 years ago (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Now, some folks may have forgotten about Chico Mendes, the rubber tapper who organized in the Amazon. Why don’t you remind us?

DYKSTRA: Chico was a union leader. He came from a family of rubber tappers. He tried to stop the exploitation of some of the workers in the Amazon. One of the issues down there is that the plantation owners would ban the teaching of math, for the rubber tappers and their families because if the rubber tappers learned how to do math, they would find out how badly they were getting ripped off by the plantation owners.

One of the things that Chico is best remembered for is that he was also working to protect the Amazon, and he became kind of an environmental icon around the world, and then he was found dead in his home. The plantation owner where he worked, the plantation owner’s son, and another worker were convicted of murder. While he was alive, and since he’s been gone, Chico Mendes has inspired the protection of millions of acres in the Amazon, but there are millions more acres every year that get cut down.

CURWOOD: Thank you, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot, Steve, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is publisher of Environmental Health News and DailyClimate.org.

And you can find links to all these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Peter Dykstra is the editor of Environmental Health News

- and the Daily Climate

- Follow him on Twitter

[MUSIC: Various Artists/Berlin Symphony Orch “The Nutcracker Suite (Baz Kuts Beats Remix)” from Christmas Remixed Vol 1 (Christmas Chill Records 2003)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...getting some skin in the game of heating and cooling our buildings. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Either Orchestra: “The (One Of A Kind) Shimmey” from Mood Music For Time Travelors (Accurate records 2013) Happy 28th Anniversary to Russ Gershon and the E/O]

Backyard Bees in Atlanta

Pollinators like bees are crucial to a secure food supply. (Laura Turner Seydel)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Eco-activist Laura Turner Seydel is passionate about living an environmentally conscious life. That includes urban homesteading - growing a garden, keeping chickens and bees. But earlier this year she had a setback in her beekeeping at her Atlanta home, as I learned during a tour of her carefully planned and designed garden.

SEYDEL: Well, it was a process getting there, first of all, we did a locally planted indigenous grouping of native plants that are drought resistant and healthy. We got rid of all of the chemicals - it’s 100 percent organic. We fertilize with our compost and worm poop so we don’t have to use many chemicals to grow our vegetables and fruits and all our beautiful flowers. And then I decided we were going to plant clover for our pollinators, and I tried to do everything in my power, here, that would really be pollinator friendly.

CURWOOD: So you brought in some bees.

SEYDELL: Well, we did. I had a local beekeeper bring a hive, and she established a colony, and we had them for about a year-and-a-half, and one day I went out there to see how they were doing, and I noticed there wasn’t any activity.

CURWOOD: Uh oh.

Laura Turner Seydel’s home in Atlanta Georgia. (Laura Turner Seydel)

SEYDELL: It was not a good sign. And Cassandra Lawson, who is an urban beekeeper, and who keeps about 20 hives around the city said, “Laura, you really have a significant problem. Your bees are dead and gone.” And I said, “Well, what happened?” And she said, “Well, I’ve never seen anything like this before.” And she said, “The bees actually encapsulated the pollen within the hive,” which tells us the pollen was so toxic, and they couldn’t get it out of the hives, so they just tried to encapsulate it.

CURWOOD: Now, bees sometimes die because they sometimes run out of food over the winter. It’s very cold, but it wasn’t too cold, they hadn’t run out of honey.

SEYDELL: That was not it at all. It was actually because I live in an affluent neighborhood, and there’s a tremendous amount of chemicals that are used to keep a yard looking perfect, and lot of the home products, the home garden products, are filled with pesticides that are very harmful to all insects, including our pollinators, and now, even in the big box stores there was a study done recently, a case study, and it was reported by Friends of the Earth a couple of weeks ago, that 50 percent of the plants being sold there, flowering plants, have this certain class of chemicals in them called neonicotinoids, which have been attributed or linked to massive bee die-offs in this country and Canada and around the world and actually the EU banned it, its use temporarily I think a two-year ban until they could prove that it was safe for pollinators.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to see what you’ve done with your yard to help pollinators.

[FOOTSTEPS]

CURWOOD: Oh, there’s lots of clover here.

SEYDELL: In the springtime, we have two different kinds of clover, we have the White clover and we have the Red clover. It’s not blooming now, but in the spring it’s a sea of white, and I can see my neighbors, and I’ve had a comment or two, it’s like, don’t let that disease come over here.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

SEYDELL: But it gives me an opportunity to really inform and educate, which is what I love to do.

CURWOOD: Are we going to have any luck here and find a four-leaf clover?

SEYDELL: I’m really good at finding four-leaf clovers, but I haven’t had much time to look recently. But we might get to see some in the back. So I’ll show you my raised beds. Come on. And I’ll even show you my chickens.

CURWOOD: Chickens here in the city?

SEYDELL: Yes, I have five chickens. Yes.

Laura Turner Seydel. (Laura Turner Seydel)

CURWOOD: Is that legal in downtown Atlanta?

SEYDELL: Oh, yes, chickens are quite legal, as well as bees.

[FOOTSTEPS]

SEYDELL: See, there they are right there. The chickens.

CURWOOD: Oh yeah. Look at that.

SEYDELL: You see? So they’re free-ranging chickens, and then they have their little coop. And there are more raised beds and a patch of strawberries.

CURWOOD: Come on chickee-chickee-chickees!

[CHICKENS CLUCKING]

CURWOOD: So the bees were right back here, huh?

SEYDELL: Yes, they were. And my beekeeper, she had never seen anything like what happened with my beehive before, you know, how the bees encapsulated the toxic pollen, and she manages bees all over the city of Atlanta, and she says her most productive hives have always been in communities of low-income because they don’t have the discretionary income to buy all the chemicals. I think that there’s a lot to be said for that. We need to be more like that, organic and chemical free, so that the pollinators can do what God made them to do.

CURWOOD: Laura Turner Seydel is an eco-activist in Atlanta, Georgia. Thanks so much, Laura.

SEYDELL: Thank you, Steve. We'll have to have you back more often. This was a real treat.

Related link:

Laura Turner Seydel’s website

[MUSIC: Frank Zappa “Blessed Relief” from The Grand Wazoo (Rykodisc 1988)

Happy Birthday Frank Zappa 12/21/1940 – 12/04/1993)]

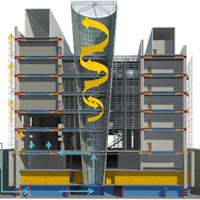

Living Walls

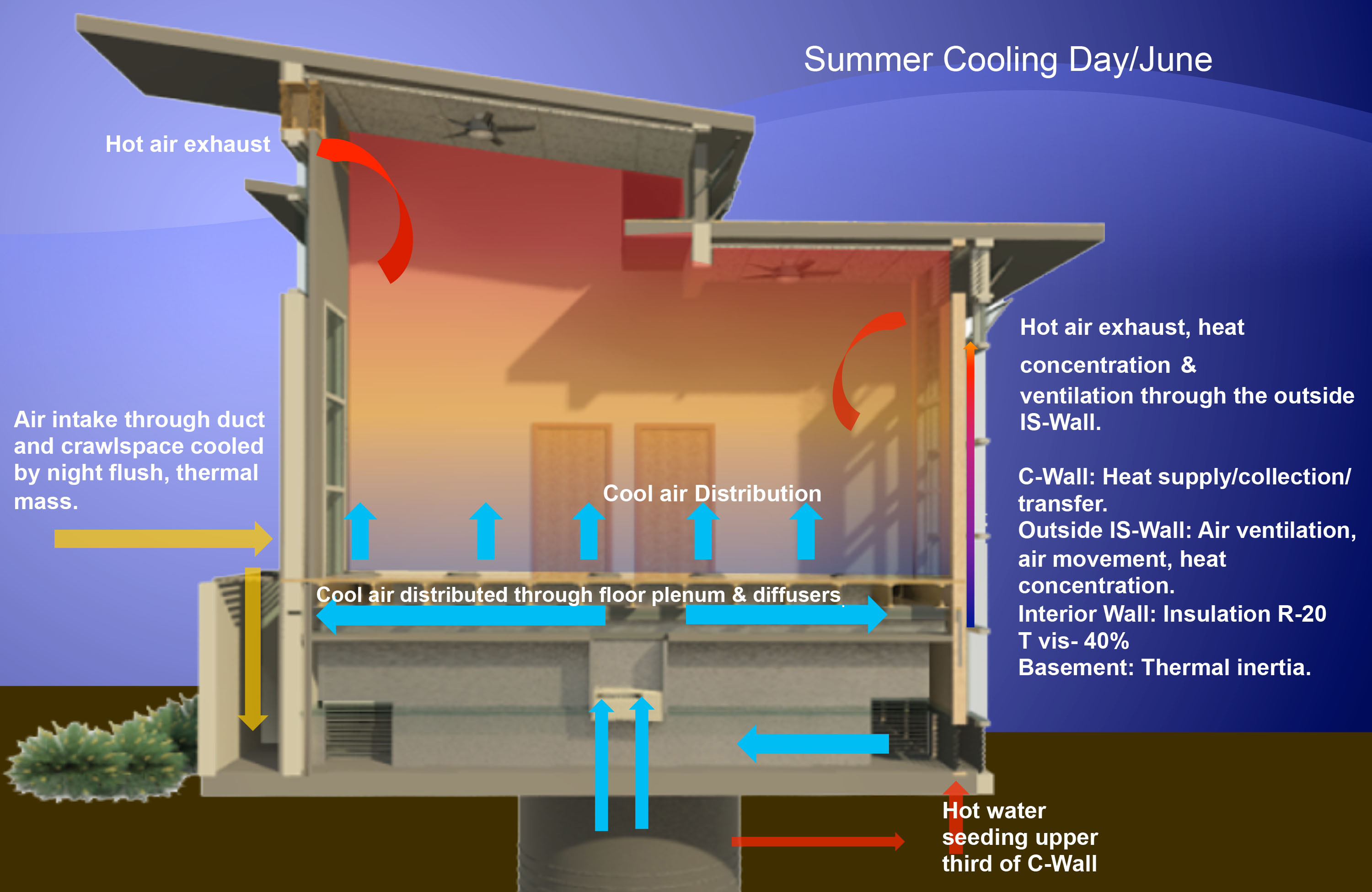

CURWOOD: When we think of ways to heat and cool our buildings more efficiently, we tend to think of better insulation, and better fuels, perhaps. But there are some extraordinary experiments that go much further, including those that mimic the way skin regulates body temperature.

From the IEEE Spectrum Magazine, National Science Foundation documentary, "Becoming Bionic", Laurie Howell reports on the Living Wall.

[DOOR OPENS]

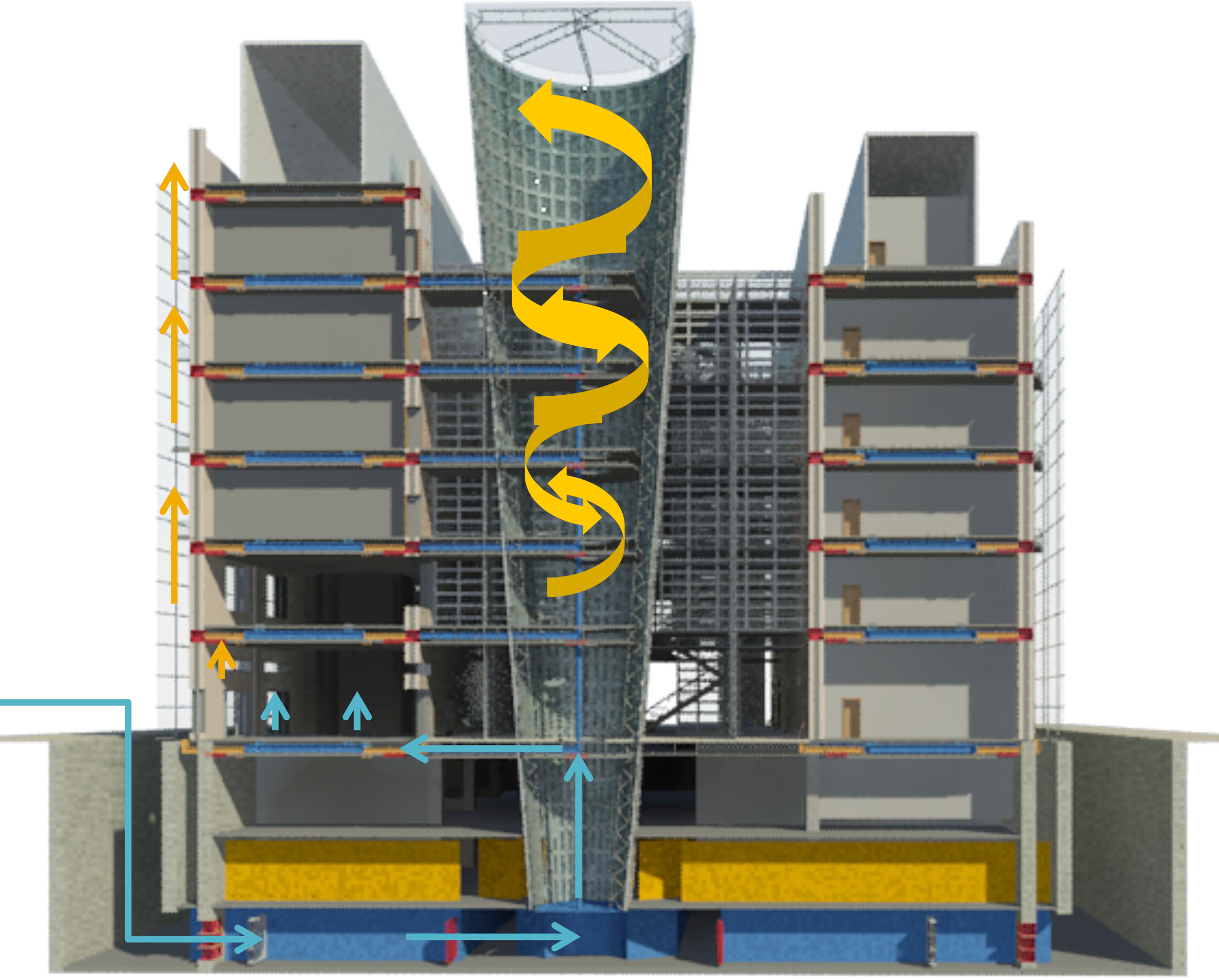

HOWELL: We begin in the Engineering Center at the University of Colorado, it’s a picturesque campus at the base of the Rocky Mountain foothills. This is where John Zhai, an architectural engineering professor, leads a multidisciplinary team of engineers and architects on a creative venture of a lifetime. They’re designing what they call a “Living Wall.”

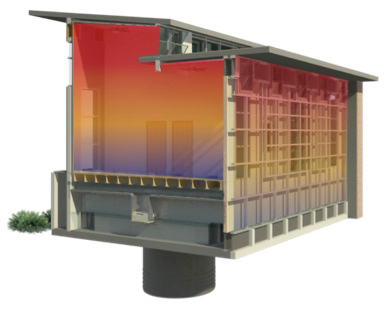

ZHAI: Traditional building designs just want to block the heat. “Hey, don't let the heat in.” We say, “OK. Let the heat in, but we're going to deliver this heat to where we need it.” Okay. So, this is our building system lab. So, come on in. So, this is the full-scale building system lab.

HOWELL: Zhai calls the Living Wall the “skin of the building” because it would auto-regulate the temperature of a building just as skin helps regulate body temperature.

ZHAI: The veins underneath the skin can take the heat from the surface to the body and also can have fat that's kind of insulation. So this automatic system is natural in our body, so if we think of the whole building as a body.

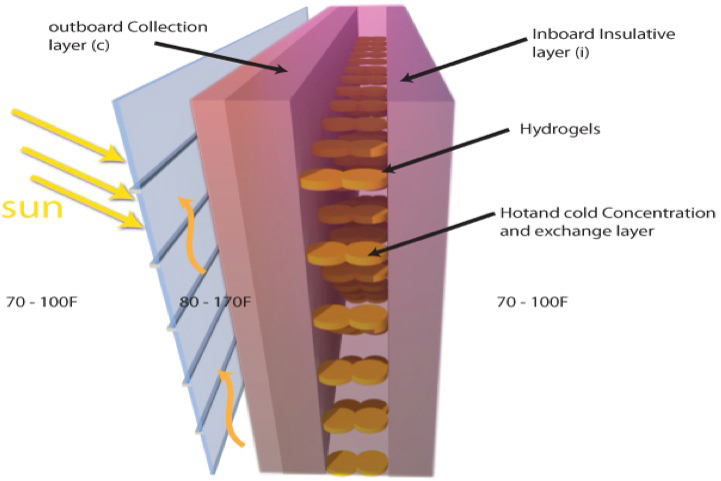

HOWELL: It’s like a human vascular system of capillaries, veins and arteries: water is collected at each floor through small tubes and pipes within the living wall, controlled through a computerized brain or building automation system. The hot water is redistributed throughout the building for heating, domestic hot water or adding heat into the shaded living walls to augment the chimney effect for cooling. The entire system works on a basic law of thermodynamics. The living walls move energy from hot to cold very rapidly and efficiently, whether collecting or distributing heat through water or air.

ZHAI: So the envelope of that's the skin. So, can we do something similar or mimic to this natural body system, which has fat insulation layers, have all these veins, blood flow, the air flow, all the stuff and then very likely we can have a building envelope that can adapt to the environment. So whatever environment is changing, the core body inside temperature is always constant. So if we can achieve that same thing that would be perfect.

HOWELL: Zhai says the living wall system could slash energy use by – get this -- 75 percent. And energy use decreases 75 percent, not by improving heating and cooling systems, but by eliminating them altogether. No more boilers or chillers to create that comfortable room temperature. The living wall system would use passive heating and cooling, working with the outside temperature instead of against it.

Zhai’s fellow CU professor Fred Andreas is the lead architect on the team putting this million-dollar prototype together.

ANDREAS: There's no reason, other than business as usual, that we heat and cool and light our buildings the way we have, as hermetically-sealed units that are disconnected from the environment. So the idea of the living wall is to turn the skin of the building into a living skin copying essentially biological processes and so trying to auto-regulate heat and cooling and ventilation and light through the skin of the building and supplant the huge HVAC systems, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems inside of any building and then using natural daylight as much as possible.

HOWELL: The outside layer will use current smart glass technology which can block or tune the sun’s rays and control how heat and light enter the wall. The next layer of the living wall is just open space for collecting and distributing passive heating and cooling. At the bottom of the wall we’ll have cool water coming in from a source, such as a river, a lake, the ocean or an underground aquifer. And the top of the wall will be hot from baking in the sun. Now think about how a chimney works and that’s what happens here: the cool-hot temperature difference produces an updraft, and that updraft passively forces hot air up, up, up inside the multi-layered walls, drawing cool air through the building and producing natural ventilation. The hotter the air, the faster it rises. So, as crazy as it is to imagine, for this passive cooling design, the hotter the wall, the better.

[DOOR OPENS]

ZHAI: That's a testing room we have here which can test all the building systems, walls, systems. So this is one of the chambers. Watch the steps.

HOWELL: We’re walking along an HVAC system which stretches for roughly 40 feet. There are two rooms which can be made any temperature… this will be where the team installs and tests its first prototype.

ZHAI: So, you see all these air systems. We have water panels here. This can provide radiation. We can simulate solar radiation so we can mimic the outside environment, so we don’t have to go outside to test the performance of the living wall.

HOWELL: The team envisions one day creating Living Wall kits for retrofitting buildings, possibly even homes. But right now, they’re focused on overcoming some puzzling design issues. Their biggest challenge is a layer in the living wall that will be made with something called hydrogels. Hydrogels are chemical compounds, or polymers, that absorb or release liquids depending on temperature… they’re used in products, such as diapers, and for a variety of purposes, such as tissue engineering. And, they are key to making the Living Wall work because when the temperature changes, hydrogels embedded in the wall begin pumping water. Depending on the temperatures outside and inside the Living Wall, the hydrogels pump hot or cold water from one side of the wall to the other, cooling or heating the building. The big challenge for these researchers right now is how to contain the hydrogels within the Living Wall:

ANDREAS: That’s the challenge is how do we get a plastic collection panel that maximizes heat collection at its best and move that heat through these flexible gels into the depth of the panel and how do we get those flexible gels into the panel in manufacturing. That's our challenge right now.

ZHAI: Right. That's why we cannot use traditional concrete or wood. We'll have to use a polymer material that's porous medium so that these kinds of materials can be embedded or attached somewhere in the polymer, those bubbles so that makes a whole piece of a wall.

ANDREAS: And here's the other challenge is it can't be glass because glass, when it's formed, is so hot that it would destroy these hydrogels, so we have to figure a way to get these hydrogels infused into this panel at a relatively low temperature.

HOWELL: This is not just another greener building design, this is a change in the way we’ll design the buildings of the future.

ZHAI: Typical systems and typical approaches with the same kind of HVAC systems although they're very high efficiency and they're very high technology, they're still using the same assumptions that we've used throughout the 20th Century. And this fundamentally changes it. Basically moves away from the idea of interior conditioned buildings to passively controlled buildings.

HOWELL: Yeah, truly, a game changer.

ZHAI: Game changer.

HOWELL: And that’s exactly why it has captured the imagination of the next generation of building designers. Grad students Tamzida Khan and Scott Rank are excited about what’s on the horizon for smart building design.

RANK: Pretty soon there shouldn't be green architecture. It should just be architecture and that should be in all of it, integrated into it. So, I think, yeah, we’ve come a long way, but I think it definitely has a lot further to go as well.

KHAN: If we don't take risk, then we will not move forward and I think it's really important for us to take risks.

ANDREAS: I keep saying to my students I fundamentally believe that they'll be looking at this period of time right now, this change to the 21st Century that they'll be looking back at this in 1,000 years as the renaissance, equivalent to the artistic and cultural renaissance that happened previously. I think that this is an architectural and engineering renaissance that we're experiencing right now at the early part of the third millennium. I think the sky is the limit.

HOWELL: In the early part of the third millennium, reporting on what’s possibly an architectural and engineering renaissance, I’m Laurie Howell.

CURWOOD: Laurie's story on Living Walls comes from the IEEE Spectrum Magazine, National Science Foundation documentary, "Becoming Bionic".

Related links:

- Listen to the rest of the IEEE Spectrum series Becoming Bionic

- Check out the website for Colorado University’s “Living Wall”

[MUSIC: James Booker “Professor Longhair Medley: Tipitina/Bald Head” from Classified (Remixed and Expanded) (Rounder Records 2013) Happy Birthday James Booker 12/17/1939 – 11/08/1983)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. We bid farewell this week to our intern Kathryn Rodway and wish her well. Jeff Turton is our technical director.Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of Red Tomato, supplier of righteous fruits and vegetables from northeast family farms. www.redtomato.org. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth