March 27, 2020

Air Date: March 27, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Warming Oceans And Toxic Shellfish

View the page for this story

Many coastal native Alaskans rely on harvested shellfish as part of their subsistence lifestyle. But mussels and clams can carry a lethal dose of a toxic chemical called saxitoxin, and as ocean waters warm, the algae that produces that toxin is thriving year-round. Grist reporter Zoya Teirstein joins Host Steve Curwood to explain why the indigenous knowledge that has long protected coastal shellfishing from this threat can’t reckon with climatic changes. (10:05)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on Earth Day gatherings for the 50th anniversary of the celebration of our planet. They also talk about ambitious reforestation efforts around the world, and in the history calendar, they look back to Earth Day 1990, when a star-studded cast took part in a primetime 2-hour Earth Day TV special. (04:31)

Major Ocean Currents Drifting Poleward

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Ocean currents play an essential role in redistributing nutrient-rich waters and heat energy around the globe. New research from the Alfred Wegener Institute finds that global warming is pushing these vital parts of the ocean circulatory system poleward. Amy Bower, a Senior Scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to discuss the impact shifting ocean currents could have on fisheries, climate, and more. (07:06)

Misfit Produce at Your Doorstep

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

The new paradigm of social distancing and staying at home is whetting consumers’ appetite for grocery delivery. And several companies that will deliver straight to your doorstep aim not only for convenience but for reducing food waste as well, by sourcing produce that isn’t uniform enough for supermarket shelves, but is still perfectly edible. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb talks with Abhi Ramesh, CEO of Misfits Market, about how it works. (07:26)

BirdNote®: Canada’s Boreal Forests

View the page for this story

Canada’s vast green boreal forests are home to almost half of North America’s migratory waterfowl and songbirds. As the mining, logging, and fossil fuel industries make increasing inroads, several Dené Indigenous Nations have come to an agreement with the Canadian government to create some of the largest protected areas in Canada’s history. BirdNote®’s Michael Stein has the story. (02:00)

The Optimist’s Telescope: Thinking Ahead in a Reckless Age

View the page for this story

Making decisions today based on what may be best for tomorrow or even years ahead is far from easy. The current moment is highlighting the perils of not planning ahead for challenges such as pandemics, or climate disruption. Bina Venkataraman, author of The Optimist's Telescope: Thinking Ahead in a Reckless Age, joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about how we can tackle shortsightedness in our personal lives and in society, to plan better for the future. (16:05)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Amy Bower, Abhi Ramesh, Zoya Teirstein, Bina Venkataraman

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Peter Dykstra, Michael Stein

THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

The coronavirus pandemic is an immediate threat to public health and the economy and better addressed by long term thinking analysts say.

VENKATARAMAN: Acting early flattens the curve. You're going to have less of a burden on health care systems and hospitals. That requires some short-term sacrifice to the economy at times but what you're really doing is preventing damage to the economy in the long run by reducing that health burden.

CURWOOD: Also, in Alaska, climate change is making subsistence seafood harvesting risky.

TEIRSTEIN: Not fishing is just not an option. So, what you'll see is that people are fishing up there and harvesting clams and mussels and other shellfish, even when researchers tell them not to, please don't, don't go to the beaches, it's not safe, you could die. And you see people disregarding that because they simply have no other choice

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Warming Oceans And Toxic Shellfish

Environmental technician Andie Wall tests blue mussels and butter clams at a traditional harvesting site. (Photo: Courtesy of Andie Wall)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The Alutiiq peoples of coastal Alaska rely heavily on fishing and harvesting for subsistence. And during the colder months of the year clams, mussels, and urchins are often on the menu. In fact, the Alutiiq has a saying – “when the tide is out, the dinner table is set.” But that way of life is being threatened by rising ocean temperatures, which are tied to an increase in saxitoxin, a poison that appears in shellfish, but which is completely colorless, odorless, and tasteless. Commercial shellfish beds are regularly tested for the toxin by state regulators, but recreational and subsistence ones are not.

And since a single clam can carry a lethal dose, while one next to it is completely safe, some now call the traditional subsistence lifestyle of the Alutiiq "Alaskan Roulette”. For more, I’m joined by Zoya Teirstein who reported this story for Grist. Zoya, welcome to Living on Earth!

TEIRSTEIN: Thank you for having me. I'm so happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So, give me a brief synopsis of this story and how it is that you came to investigate it.

TEIRSTEIN: The story is about climate change and how it affects people's lives from the very smallest things all the way up to the biggest. It's about Alaskan clams and shellfish really, and how tribes there, in a little town called Kodiak, are coping with the fallout of climate change, which is making their shellfish hauls toxic with this really kind of insidious toxin that can make you very ill and even kill you. I first found out about the poison itself, saxitoxin, at a conference in Woods Hole for science journalists. We had been hearing from researchers all day. And then finally this guy got up in front of us and he started talking about this algae. The algae are what carry this toxin, saxitoxin.

CURWOOD: So, Zoya, are we're talking about the red tide here?

TEIRSTEIN: No, not necessarily. Sometimes this toxic algae is present when there's a red tide. But it can also be there when there's no red tide.

CURWOOD: So, these toxic algae with the saxitoxin, what color is it?

Butter clams awaiting tests. (Photo: Zoya Teirstein, Grist)

TEIRSTEIN: Well, that's part of the problem. There is no color, there's no visible effect in the water. You can't tell if it's there or not. It's an invisible killer.

CURWOOD: So, let's say someone eats a clam or mussel that has the saxitoxin in it. What happens then? And what are the health consequences of this?

TEIRSTEIN: It really depends. People eat shellfish all the time in Alaska. And there's not necessarily any effect. However, if you bite into even just one clam, and this is what I opened the story that I wrote for Grist about, a woman who got sick when she was young and now no longer eats clams. If you bite into one that's very hot, that's very toxic. You can have some really serious effects. So what happened to her, her name is Phyllis Clough. She started getting numb in her mouth and lips, and sort of like a tingly sensation. It spread to the rest of her face. And luckily for her, she knew what to do, she, which is actually an indigenous technique, she made herself throw up. And that stopped her from feeling the full effects of the clam. People who are not so lucky can have a full-on lockdown. It's called paralytic shellfish poisoning for a reason, it paralyzes your system so your lungs can't breathe in air. And that's how deaths occur.

CURWOOD: Hmm. By the way, Zoya, have you eaten any clams after you've worked on this story?

TEIRSTEIN: No, I have not. What's important for me to note is that if you're eating clams or mussels in a restaurant, you're safe. This applies to recreationally fished shellfish. So for most people, that's not an issue. Most people I know are not going out in the morning and hunting for butter clams. But in Alaska, the average person pulls in 375 pounds of wild food a year. That's almost a pound per person per day, and close to 100% of the rural population in Alaska depends on foraging and hunting. And nearly half of those rural harvesters are Alaskan Native. It's a large number of people who are depending on this food to survive. So, basically, this issue affects them more than it would the average American.

CURWOOD: Now, I imagine this toxin has been in shellfish for as long as anyone could remember. So, in the past, how would people avoid this?

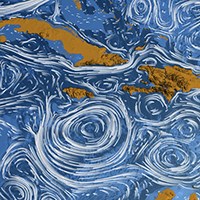

TEIRSTEIN: If you look at data from the past few decades, and it's limited, but it's there, thanks to the efforts of some very dogged researchers. There's a rule, it's the "R rule", people in the region follow it in order to stay safe. In months without an R in the name. It's not safe to hunt for shellfish. So we're talking May, June, July, August. Months with an R in the name are safe. And that's because those months are generally, or they have been generally, colder. And during cold months, that algae that are toxic don't thrive, it hibernates on the ocean floor mostly in hard little cysts.

This graph examines the monthly water-temperature deviations from average in the Bering Sea, where Kodiak Island is located. (Photo: Clayton Aldern, Grist)

CURWOOD: And just to be clear, even though it's not ever a perfect measure of safe shellfish, it was more or less considered, well, least relatively safe to eat in those months with the "R", is that correct?

TEIRSTEIN: Yeah, exactly. Many people ate during that time and still do.

CURWOOD: So, the old saying that you can eat shellfish during any month that has an R in it, to what extent has the lengthening summer or the shorter winter, however you want to put it, changed that way of guarding against toxic shellfish?

TEIRSTEIN: So, what's happened with climate change and with warming ocean waters and warming shoulder seasons, we're talking April, and then October, sort of the spring and fall, is that all those rules that people lived by and stayed relatively safe with, although people still have died in Alaska for years and years, those rules no longer work at all. As the ocean warms, that algae are prevalent year-round. Clams are toxic year-round, even in the dead of winter is what one researcher told me in Kodiak. So, the danger there is that people go to the beaches to harvest following that one rule, the "R rule" in April, for example, it's a month with an R in the name, and they haul in a catch that's really, really toxic.

CURWOOD: Some might say, well, people should just avoid eating shellfish. What do you say to someone who suggests that diet for this community, which has this as important subsistence food,

TEIRSTEIN: I've heard that a lot in the course of my reporting, mostly from folks who have never been to Alaska or don't understand the importance of shellfish for the communities there, particularly for Native communities, a quarter of whom live under the poverty line. So, for many folks up there, subsistence fishing and harvesting is a main source of food; without it, people go hungry. I had one person tell me that growing up, all the Native kids in his village knew where to find butter clams and mussels. And if you didn't know where to find them, you'd starve. So, it's really sort of a matter of life and death for a lot of people. And not fishing is just not an option. So, what you'll see is that people are fishing up there and harvesting clams and mussels and other shellfish, even when researchers tell them not to, please don't, don't go to the beaches, it's not safe, you could die. And you see people disregarding that because they simply have no other choice.

CURWOOD: So, if warming temperatures increased the frequency of toxic shellfish, what kind of impact might that have on Native Alaskans?

Phyllis Clough (left), her brother, Sven Haakanson, and her mother, Mary Haakanson are part of Alaska’s Alutiiq tribe. Phyllis once ate a toxic clam and suffered from Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning. (Photo: Courtesy of Sven Haakanson)

TEIRSTEIN: That's the thing, we don't quite know the scope of the damage or the foreseeable damage yet. Part of the problem is that there is no system in place, both for monitoring shellfish on the coastlines and for keeping track of people who have gotten sick. If you get sick with PSP or other algae borne illness, you have to call it into the state's Department of Health. A lot of people don't know what that number is, they don't know they have to report it. The symptoms can be commonly confused for the flu, or even for a heart attack if you eat enough of the toxin. So, really, the numbers the state has on file for how many people have gotten sick are not at all indicative of the scope of the issue. What one state official told me was that it's just the tip of the iceberg. There's definitely a lot more cases that aren't reported to the state. So really, right now, researchers are scrambling to create some sort of safety net for people who might get sick. They're trying to protect the community at all costs. There's not enough of them, there are not enough resources to go around. So, people will probably get sick and they will likely die.

CURWOOD: So, what about this problem is unique to Alaska? I mean, why doesn't the rest of the country have to worry so much about paralytic shellfish poisoning?

TEIRSTEIN: Every other coastal state in the nation has a system in place to protect its subsistence fishers. Here in Washington state, where I am, you can go to the beach and you'll see signs. Either it's closed or under advisory or it's open for shellfishing. They test the water there really frequently and they test the shellfish, so you can go to the beach and feel some level of safety about what you're going to do. In Alaska, there's no system like that. So, that's why it's a large problem there for people who want to subsistence harvest.

CURWOOD: And what do people tell you is a solution here?

TEIRSTEIN: Well, that's the tricky part. The solution, as far as I can tell, is very much homegrown. In Kodiak, where I was reporting the story, a band of researchers and volunteers and Alutiiq folks and the Sun'aq, which is another tribe native to the area, have banded together to create a system, so they test the beaches that are commonly fished at and they try and arm the community with the facts they need to harvest safely. The problem is that it's not a well-funded system. It depends on whether the researchers are available that day. If someone gets sick you lose a day of data. So, it's definitely not the same kind of system that other states have.

CURWOOD: Zoya Teirstein is a reporter at Grist. Zoya, thank you for your time today.

TEIRSTEIN: Thank you.

Related links:

- Grist | “Alaskan Roulette”

- More from Zoya Teirstein

[MUSIC: Mike Block, “Lay Down Your Weary Tune” on Walls of Time, by Bob Dylan, Bright Shiny Things Records]

Beyond the Headlines

An Earth Day crowd in 1970. (Photo: University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's take a look beyond the headlines now with our usual guide, Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org, and DailyClimate dot org. And we reach him on the line in Atlanta, Georgia, I hope; Peter, you're there, right?

DYKSTRA: I'm here, Steve. Hi.

CURWOOD: What do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, let's take a look at Earth Day this year, we're less than a month off -- less than 25 shopping days till Earth Day, folks! And we don't know if there are going to be any big events at all. Of course, there are no mass gatherings around the world right now because of social distancing. If you go back to 1970 and the first Earth Day, there were millions of people that showed up in celebrations in cities and towns around the globe. That's clearly not going to happen. Back then, the environment was a phenomenon as a political issue, so much so that even Richard Nixon had to sit up and take notice. This year, in terms of big public displays, not much.

CURWOOD: So what are the organizers doing? I mean, there's a whole Earth Day movement, I thought, around the planet, they have offices and everything, what are they going to do?

DYKSTRA: Sure. Well, there are obviously opportunities with social media, and with the entire cyber world, where you don't have to be six feet away from your closest neighbor. But that's not gonna have the same effect as the mass rallies we've seen in places like New York and DC and elsewhere all over the world.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I wish that we'd solved all the problems, then an Earth Day wouldn't be necessary to remind people. Hey, what else do you have for us this week?

Countries around the world are undertaking massive reforestation efforts. (Photo: Shrinivaskulkarni1388, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

DYKSTRA: How about a little good news, on reforestation. Germany's Deutsche Welle compiled a list of 11 countries, kind of a tree travelogue; most of these countries are rarely thought of as environmental pioneers, like China and Niger and Iraq. All of them have aggressive reforestation efforts underway. You remember in Donald Trump's State of the Union speech this year, even he made mention of a trillion trees being planted around the world, that initiative that the US is set to take part in. It was the only environmental mentioned in the State of the Union speech, but around the world, people are already making good on it.

CURWOOD: And as I understand it, trees soak up a third of our emissions from our activities as humans but we cut down so many that the net effect is only about a 10% carbon sink. So hopefully this move to have more afforestation or reforestation will start to change that balance.

DYKSTRA: Right, and I'll give you a few examples; in Peru, they're literally making up for lost ground from deforestation. In Romania, there's a huge illegal logging problem. And in India, the soil there is literally exhausted from intensive farming in some areas. Tree planting will help turn some of those exhausting soils to a different use.

CURWOOD: And the special trees they can grow in India and elsewhere, the mangroves, really sequester a lot of carbon.

DYKSTRA: Right.

CURWOOD: Let's take a look back at the history books now, Peter, and tell me what you see.

DYKSTRA: Let's do some more Earth Day.

CURWOOD: Okay.

DYKSTRA: On April 22, 1990, the 20th anniversary of the original Earth Day, there were six-figure crowds in DC and New York and big crowds in LA and Paris and Sydney and around the world. Earth Day and the environment was such a political phenomenon in that year, that in the US, there was a two hour primetime ABC TV special on Earth Day with an entirely A-List cast.

CURWOOD: Ah, so tell me!

The title card for The Earth Day Special, 1990. (Photo: ABC, Wikimedia Commons)

DYKSTRA: All right, here we go, a little rundown of the cast . . . Bette Midler, Danny DeVito, Dan Aykroyd, Chevy Chase, Bill Cosby -- wonder what happened to him -- Kevin Costner, Rodney Dangerfield, Jane Fonda, Morgan Freeman, Dustin Hoffman, Magic Johnson, Jack Lemmon, Meryl Streep, Betty White, Robin Williams, Barbra Streisand. And Steve, one final one: the game show host who appeared on Earth Day 1990.

CURWOOD: Who is Alex Trebek?

DYKSTRA: That's correct! Celebrities for 100.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Thank you, Peter. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org, and dailyclimate.org. We will talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon. Stay safe and stay healthy.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's LOE dot ORG.

Related links:

- POLITICO | “Climate activists shift gears in an age of ‘social distancing’”

- Deutsche Welle | “The good news about reforestation”

- About the 1990 Earth Day Special

[MUSIC: Gerry Gibbs Thrasher Dream Trio, “Brazilian Rhyme” on We’re Back, by Earth, Wind & Fire/arr. Gerry Gibbs, Whaling City Sound]

CURWOOD: Coming up – a home delivery service for produce that’s not pretty enough for the supermarket. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gerry Gibbs Thrasher Dream Trio, “Runnin’” on We’re Back, by Earth, Wind & Fire/arr. Gerry Gibbs, Whaling City Sound]

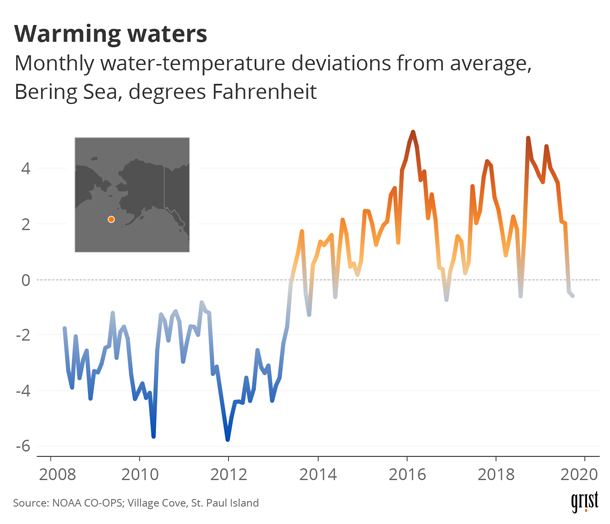

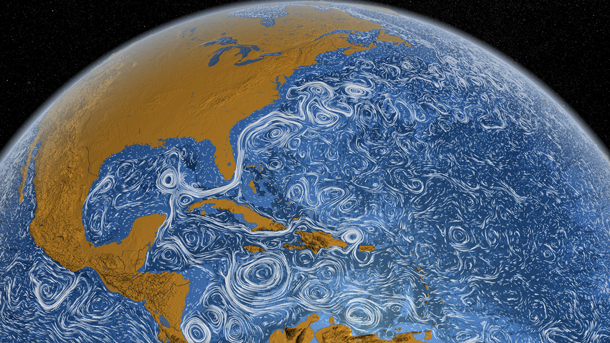

Major Ocean Currents Drifting Poleward

Ocean surface currents around the world during the period from June 2005 through December 2007 near the Gulf Stream. (Photo: NASA Goddard Photo and Video, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Seventy percent of our planet is made up of the oceans, and its major currents move vital nutrients and heat around the world. For instance, the Gulf Stream warms the beaches of the east coast of the US and then loops across the North Atlantic to bring a mild climate to the British Isles. Now research from the Alfred Wegener Institute finds that climate change is pushing some of these ocean currents closer to the poles. Amy Bower is a Senior Scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

DOERING: So first Amy, I wanted to ask you why are these ocean currents so important to life on Earth to the oceans, the health of the oceans, and also to life on land.

BOWER: Ocean currents are really critical to life on Earth, both in the oceans and on land. They redistribute the heat and energy that comes in from the sun, because of the shape of the earth being a sphere. As you go to the north and south poles. The sun rays are a bit of an angle and so the energy from the sun per square mile is less. If the ocean currents and the atmosphere did not take some of this extra heat that comes to the equator and move it to the poles. the equator would get hotter and hotter and hotter and the poles would get colder and colder, colder and life as we know it could not exist. The ocean currents also transport nutrients and dissolved oxygen which are needed for microscopic plants together. grow in the upper layers of the ocean where there's sunlight and the oceans redistribute oxygen and nutrients around to various locations,

DOERING: Can we take a step back and look broadly at how the ocean currents work on Earth?

BOWER: Ocean currents on Earth are driven in two different ways. One way is by the winds blowing over the oceans. This is the one that most people would be familiar with, because the winds are most important in driving the surface currents. And some of the currents they might be familiar with include the Gulf Stream, which flows northward off the east coast of the United States. The second way is by differences in density when some waters in the ocean are denser than others that will force the denser waters to try to move under the lighter waters. And that also generates especially deep ocean currents.

DOERING: So what's happening now based on this new research and research in the past on global ocean currents, and how they're shifting poleward. Why is that happening?

Schematic diagram of the major wind-driven ocean circulation (black arrows) and their movement (white arrows) under global warming. (Photo: © Yang Hu, Alfred-Wegener-Institut)

BOWER: Well, these authors argue and show evidence that because of the increasing heat, the winds in the atmosphere are shifting as well. They are shifting poleward. And because the winds are responsible for where the surface currents are, as those winds shift, the surface currents will also shift. And so they are showing evidence that there has been a poleward shift of some of the biggest currents and the largest covering the most area. There's been a shift. It's a small shift, but they argue that it is an indication of bigger shifts to come in the future.

DOERING: And what currents are we talking about that are shifting poleward?

BOWER: One example of these poleward shifting currents that they argue is what's called the western boundary currents. These are intensive currents on the west. Western boundaries of all the major ocean basins in the North Atlantic. That current is the Gulf Stream. And there are others around in the southern hemisphere. And those western boundary currents and their eastward extensions kind of out into the middle of the ocean are what these authors are saying are pushing poleward. So that means towards the north pole in the Northern Hemisphere and towards the south pole in the southern hemisphere.

DOERING: Fascinating. So I understand these ocean currents, they're huge. They're basically invisible to the human eye, right? What kinds of tools can scientists use to actually study how they work and how they're moving poleward?

BOWER: There are multiple ways the authors of this paper have used one of our most valuable tools for studying the ocean on a global scale. And those are satellites flying overhead that measure the ocean temperature. They also indirectly measure the ocean currents at the surface. They give us the broadest possible picture of what's happening all over the globe at the same time, because every few days, you get a complete snapshot of the surface temperatures and the surface currents.

DOERING: So we've already heard a little bit about atmospheric changes because of climate change. And I'm curious about how that relates to the oceans, and how ocean currents moving poleward how's that going to affect hurricanes and other kinds of storms that we experience?

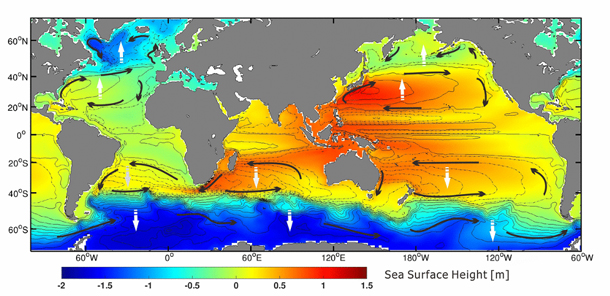

Climate fluctuations lead to shifts in ocean circulation that can cause fish populations to rise and fall. (Photo: Deborah Friedman, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BOWER: The ocean currents, some of them carry a lot of heat. And the heat is the energy for many atmospheric storms. That includes hurricanes, cyclones, they derive a lot of energy from the heat carried by the oceans, because the storms are more likely to develop into severe storms where there's more heat available. In that case, it's not so much the shift in location, but just the physical warming of the currents may lead to stronger hurricanes.

DOERING: So how could changing ocean currents actually affect fisheries as well?

BOWER: Ocean currents transport nutrients, how they transfer those nutrients around determines where the most productive areas in the oceans are. So if the ocean currents shift, that means they're going to carry their nutrients elsewhere. And so a fishery that was, depending on the ocean transport of those nutrients to a particular region may find that those nutrients aren't coming there anymore. And that fishery will decline, the fishery may move to a different area, maybe one near where people live, maybe not. So again, if these currents shift around, the whole ecosystem could shift in order to maintain or find an area where the temperatures they're adapted to are maintained.

DOERING: To what extent do you think that it might already be too late to prevent some of these changes that we're seeing?

BOWER: I think of the oceans as a giant flywheel of the Earth's climate system. And that flywheel is getting quite a bit of momentum now in a certain direction of warming, I don't believe there will ever be too late. This is an ongoing issue. We need to start now and maintain our efforts towards reducing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. As long as we keep doing it, the climate will keep changing and moving. It's not going to reach a steady state. So the sooner we get started, the better off we'll be.

CURWOOD: Amy Bower from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related link:

More about major wind-driven ocean currents shifting poleward

[MUSIC: Desert Dwellers, “Traversing the Endless Road” on Breath, by Desert Dwellers, Black Swan Sounds]

Misfit Produce at Your Doorstep

Much of US food is wasted because of aesthetic imperfections, like with this twisty carrot. (Photo: Brett Forsyth, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: To slow the spread of the coronavirus many people are limiting travel outside the home to essential tasks like getting medical care and going to the grocery store. And there are ways to get fresh food delivered. Several companies including Hungry Harvest, Imperfect Produce, and Misfits Market work with farmers to collect produce that isn’t quite good enough for supermarket shelves but is still perfectly edible. They’ll pack them up and deliver weekly straight to your door. Abi Ramesh is the CEO and Founder of Misfits Market, and he spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: So what does Misfits Market do? Can you please explain your business model to us?

RAMESH: Absolutely. So the simplest way of describing it is, we essentially rescue a lot of different types of products that would otherwise go to waste in our food system. And we ship it directly to households. And the idea is that you can save money, and also help combat the global food waste problem, by buying food from Misfits Market.

BASCOMB: And what kind of farms do you work with to get your produce?

RAMESH: Yeah, so we make it a priority of ours to work with non-commercial farms. And so we work with a pretty large variety of small, medium-sized, and some that are even larger farms, but they do not sort of like big, big agricultural, commercial farms. And we work with them to sort of determining the product that they otherwise wouldn't be able to sell, or a lot of times product that would be going to waste on the fields, going to waste in transit and storage. And we figure out what is consumable for human consumption and we repurpose it and ship it directly to people.

BASCOMB: And why would it otherwise be going to waste?

RAMESH: Yeah, so there's a lot of different reasons why, you know, food can go to waste in our food system. We generally think about it and bucket it into a sort of three big buckets. The first one is an aesthetic reason. So there's a lot of produce, that simply wouldn't look great if it were sitting on grocery store and supermarket shelves. And so a lot of the large supermarket and grocery store chains won't actually go and purchase, you know, certain types of produce from growers, if it just looks off, right, if it's an apple that's not perfectly spherical if it's butternut squash that's shaped a little bit weird. If it's a cucumber that's too curved. So things that just have aesthetic imperfections, scarring falls in this category as well. That's one big bucket. The second big bucket is size constraints. So we'll have products that are either too small or too large to sort of fit into the size restrictions that regular buyers would want. So we see some of that. And the third bucket, which I think a lot of people don't necessarily think about, is simply excess. So you know, nature operates in interesting ways and isn't necessarily always predictable. And buying patterns from large supermarkets and grocery chains are also not super, super in line with what growers are producing. So the food system produces a lot of excesses accidentally, and we're able to purchase that and sell it to our subscribers at a big discount.

BASCOMB: And where would these imperfect and excess fruit and vegetables go if not for services like yours?

RAMESH: So today, there's not really--the short answer is there's not really an outlet for them. So if a grower is not able to sell stuff, they'll either toss it or they'll end up leaving it in the ground. So we, a lot of times we'll see farms that choose not to harvest something that they've grown just because they think there's not a market for it. And so all of the time, energy, and actual sort of resources that have gone into growing that product go to waste because they get tossed. Sometimes we'll see that something is in transit, it goes to the wrong place, there's no place to store it so it gets dumped at a dumping or composting facility. So usually this stuff gets thrown out today.

BASCOMB: I mean, surely it could end up in a food pantry or something like that, though?

RAMESH: It's a good question. And I wish a larger chunk of it already did, the way the system works today. But unfortunately, if you look at the spectrum and the scale of all the farms and growers out there today, there's a very, very, very small number of them that actually have the infrastructure today to go and ship items consistently to food banks and food pantries. There's a very small number of food banks and food pantries that have the infrastructure to even go pick up stuff if they had to do that. So the answer is that a very small percentage of food waste would go to food pantries, and that's food waste that you know, we're not touching today. But the vast majority of it, it doesn't because that infrastructure doesn't exist. So we actually, at Misfits Market, we sort of see ourselves as building that kind of piping and that infrastructure where it didn't exist already. So we're aggregating food from a lot of different growers. We sell what we can to folks that want to save food, want to eat more affordably. And then we actually donate a pretty large chunk of it to food banks and food pantries.

BASCOMB: And I imagine, too, for the farmers, I mean, they have to pay somebody to go out and pick the beans and pick the squash. That's also expensive.

Not all tomatoes are beautiful. But even the ugly ones may be perfectly edible! (Photo: Silke Baron, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

RAMESH: Exactly. Right. So because you know, for example, we work with a farmer that grows eggplant, and a lot of, like, the eggplant that's too small to actually sell to grocery stores, he leaves in the field. And if we said hey, can you just donate that, you know, for free? His answer would be, I guess I could, but someone, you know, someone has to sort of cover the cost of labor, cover the cost of transportation, of storage, for me to actually go do that. And so what we're saying is, hey, we'll do that. And so it's a win for you, and we'll actually pay you a little bit more than that, actually a lot more than that, so you make money on it. This is income that that farmer would not have had before. And so not only are they covering the cost of taking the produce, of storing the produce, of shipping the produce, they're also making money on food that they've grown and they're not harvesting otherwise.

BASCOMB: Now, how do you know that the produce in a Misfits Market box would actually have gone to waste? I mean, an ugly carrot, for example, can still be shredded, or a bruised tomato can be made into sauce or something, right?

RAMESH: Yeah. So you know, in theory, in a perfect world, in a very efficient system, you know, every farm that grows carrots, or every farm that grows tomatoes, also has an avenue for shredding carrots or canning tomatoes, or creating, you know, for apple growers, they have a way to create cider. But again, it's one of those things where the food system is quite inefficient as it is today to the point where, for every one grower that has access to, you know, a carrot shredder, there are twenty other carrot growers that do not today,

BASCOMB: Looking down the road, what do you see for the future of Misfits Market and this idea of avoiding food waste more generally?

RAMESH: Our goal over the next couple of years is to really grow Misfits Market to be a national brand that sort of embodies a lot of things we want to embody around the affordability of food and sustainability and food waste. And my hope is that, as we do so and as we grow, we can involve more people in the food system, and really sort of push the envelope a little bit more when it comes to food waste. And also in the process, educate households and consumers on what they can do on their end to sort of tackle that food waste problem. And so our goal is to provide consumers with little tidbits that they can take and use on a daily basis so that at scale, we're able to kind of make a much larger impact.

BASCOMB: And can you give me one or two of those tidbits? Maybe somebody's not quite ready to sign up for weekly delivery, but what can they do in the interim?

RAMESH: Yeah, yeah. And our blog is a really good place for this. So we're putting out a post about how you can pickle and jar certain things in a very easy manner in your home, and it allows for a lot of things to last longer. We're teaching folks how they can, you know, use every single part of a piece of fruit and vegetable instead of throwing it away. And there's really fun things like you can even, you can use orange peels and grapefruit peels in your cocktails, you can create broth using pieces of fruits and vegetables that you probably wouldn't have used and could have tossed. So I think all of those are little examples. We're hoping we can add those and create a really big blog out of them.

CURWOOD: That’s Misfits Market CEO Abhi Ramesh speaking with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- The New Republic | “Does Your Box of “Ugly” Produce Really Help the Planet? Or Hurt it?”

- Food & Wine | “Why the Business of Ugly Produce Is So Complicated”

- Misfits Market

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Canada’s Boreal Forests

The olive-sided flycatcher resides in Canada during the breeding season. (Photo: © Gregg Thompson)

CURWOOD: BirdNote’s Michael Stein reports NATIVE peoples in Canada have been instrumental in protecting one of the most important bird habitats in the world.

BirdNote®

Conserving Canada's Boreal Forests

[Songs and calls of birds that breed in Canada’s boreal forest]

The vast Canadian boreal forest provides breeding habitat for up to three billion of North America’s migratory ducks, geese, and songbirds. Add the young raised over the summer, and there may be as many as five billion birds.

An olive-sided flycatcher sits atop a tree in the boreal forest. (Photo: © Tom Munson)

[Croaking and “conversation” of ravens]

The boreal forest is “one of the largest intact forest and wetland ecosystems remaining on earth.” But the boreal is under increasing pressure from logging, mining, the development of the petroleum, infestations of pine beetles, and climate change. [Call of Boreal Chickadee]

However, Indigenous Nations are protecting boreal forest lands on a sweeping scale. In 2019, the Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation worked with the Canadian government to create one of the biggest protected areas in the country. The Sahtu Dene is planning to conserve an area 12 times the size of Yellowstone.

The boreal forest can seem endless from ground level, but extractive industries are making inroads. (Photo: Keith Williams, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

And the Sayisi Dene want to preserve over 12 million acres—habitat for millions of nesting land birds and tens of thousands of migrating waterfowl.

The biggest, most ambitious proposals for conserving lands in Canada are coming from Indigenous Nations. And these lands offer hundreds of bird species the best chance to adapt and thrive into the future.

###

Adapted from a script by Todd Peterson

Thanks to Emily Cousins at BorealBirds.org and to Jeff Wells at Audubon for their assistance.

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Sound track of the boreal forest recorded by G.F. Budney. Calls of Ravens and Sandhill Cranes were recorded by G.A. Keller; Boreal Chickadee by G. Vyn.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

Editor: Ashley Ahearn

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2020 BirdNote February 2020

ID# SotB-boreal-01-2011-02-01 SotB-boreal-01b Narrator: Michael Stein

https://www.borealbirds.org/announcements/1500-scientists-worldwide-call...

https://www.birdnote.org/show/conserving-canadas-boreal-forests

CURWOOD: For pictures fly on over to the living on earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Listen to this story at the BirdNote® website

- Click here to read more about Thaidene Nëné, the first of the conservation areas to become finalized in cooperation with the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation

[MUSIC: Eugene Friesen, “Still Life With Moose” on In the Shade Of Angels, by Eugene Friesen, Fiddle Talk Music]

CURWOOD: Coming up, why it can be hard to think ahead, and some ways to make it easier. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt, and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Bill Miller, “Wind Spirit” on Native America, by Bill Miller, on Putumayo World Music]

The Optimist’s Telescope: Thinking Ahead in a Reckless Age

Women of the St. Louis Red Cross Motor Corps carrying stretchers during the 1918 influenza pandemic. The city of St. Louis had a quick and effective response to the pandemic and was able to significantly lower potential death compared to other cities throughout the United States. (Photo: GPA, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Making decisions today based on what may be best for tomorrow or even years ahead is far from easy, especially when there are immediate costs. Addressing climate change is one example, as it can reduce short-term profits and increase expenses for many businesses, even as it boosts long-term prospects. And we are all too aware how budget cuts in US public health services and a lack of planning for pandemics landed us in the throes of the current coronavirus crisis. But in her new book, The Optimist's Telescope, thinking ahead in a Reckless Age, journalist Bina Venkataram writes there are ways to tap higher levels of thinking that can lead to actions for better futures. Bina Venkataraman is a former climate advisor for the Obama Administration and Editorial Page editor for the Boston Globe and she joins me now. Bina Venkataraman, welcome to Living on Earth!

VENKATARAMAN: Thanks so much for having me, Steve. I'm glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So we're in the midst of a novel coronavirus pandemic, what parallels, if any, do you see between people's inability to look over the horizon at the implications of climate change climate disruption, and the implications of a possible pandemic?

VENKATARAMAN: There's a lot to learn here. There's a lot of parallels. So the optimist telescope was really my attempt to write down a collection of insights about how we can think ahead better and some of the insights, you know, the opposite has been sort of what has happened. And if you look at it from the United States point of view, you know, in late January, when we had our first case appear in the US, you had leaders or our president in the White House, saying this was not a big deal that this is all going to go away and be fine, that the risk is low. You even had an attempt to sort of not count the cases. He was hoping to keep the number lower, he somehow thought if he left some cruise ship passengers out at sea, that that would keep the numbers lower in terms of Americans who'd be diagnosed with this. Well, you know, if you don't count them, it still becomes a problem down the road. So quite a bit of short-sighted thinking. If you think about it, from the point of view of society, I think a lot of us have been reluctant to recognize this threat coming over the horizon. And one of the insights from the Optimist's Telescope about why that happens, you know, we fail to prepare for what we can't easily imagine or what we haven't already experienced. So for a lot of people having an epidemic of this kind of scale and proportion, where it's this contagious, and this potentially deadly is not something that they remember in their lifetime. But a lot of the actions that are needed to prevent the spread of a virus like this have to be taken at an early enough stage to be effective. So if you can aid people's imagination and help them really take these things, threats of the future seriously, then you can do a lot better. And I'll tell you one thing that's really interesting in this case for the United States is that we can look to what's been happening in Italy because we're days behind Italy's trajectory in this epidemic.

CURWOOD: So a while back, we spoke to a physician, Jonathan quick. He's been with the World Health Organization, he teaches at Duke now. And he pointed out that back in 1918, at the great flu pandemic, they call it the Spanish flu, even though it really was all over the place. There was a public health officer in St. Louis, Missouri, who organized people. And Dr. Quick says that the death rate in St. Louis was about a quarter of the death rate in other big cities, some of the other big cities, simply because this fellow got out and really got people organized. got everybody aboard, because he was looking over the horizon of what could happen. Dr. Quick also pointed out that we have about 45,000 fewer public health workers than we had some time back before the other economic meltdown, we're most familiar with the one back in 2007, 2008. In other words, those people were let go because there was not seem to have an immediate need for them. We overlook decisions that really will contribute to our well being, like, you know, skipping a workout or procrastinating our responsibilities or like having a full-throated public health service available for when trouble comes. Why do we have so much trouble looking ahead?

A 1919 World War I Victory Parade brought people together even though the Spanish flu was still a pressing danger. (Photo: USMC, George Barnett Collection, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

VENKATARAMAN: Well, if you think about it, the future doesn't really exist. yet. The future is not something we perceive with our senses. We don't smell it, we don't taste it. We don't see it right in front of us. So we conjure it with our minds, it's a figment of our imaginations. And the fact that human beings can do this is actually somewhat miraculous. We may be the only creature that can do this. It's not confirmed yet. But we do have this capacity to sort of dream up what the future could look like we use our past experiences to project ourselves into future scenarios, what's known as episodic memory, but it's an imperfect skill. So we have to really stretch ourselves when we're talking about unprecedented change, unprecedented scenarios, things we don't have in our memory. But it's interesting that people are talking so much about the 1918 influenza epidemic because that does provide us a way to try to imagine the scenario and the people who've studied that history, I think in some ways are those who have been able to give the right kinds of warnings to prepare for what's been happening around this novel coronavirus pandemic. And one of those insights, for example, is that gatherings large gatherings like the World War I victory parades that were happening in cities like Philadelphia and Boston in 1918 turned out to be accelerators. They turn out to be pivotal events that spread the disease to more people. So some of what we can use to conjure the future comes from not just our own experiences, but the experiences of other human beings which get carried forward by stories by keeping the past very much alive in our imaginations. And one of the stories I tell in the Optimist's Telescope to this point is about the engineer who was responsible for designing the nuclear power plant in Okinawa, Japan. Now Okinawa, for those who don't know, was closer to the epicenter of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami than the infamous Fukushima Daiichi which we know the disaster that happened there when the reactors melted down. And that happened because the tsunamis breached the seawall there in Fukushima and flooded the reactors now. In Okinawa, the nuclear power station was a place of refuge for people in the town during the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. And the reason for that is a man named Yanosuke Hirai, this engineer I described to you had insisted that it'd be built farther back from the coast and at a higher elevation with a higher seawall. And you might wonder why well, he knew the history of his hometown shrine, which in the year 869, had flooded due to the Jogann earthquake and tsunamis that followed that. So this is very much an important insight about what it takes to think ahead, what makes it easier or what empowers certain leaders to be better able to imagine a future on behalf of the rest of us and prepare us for what's to come and keeping the past alive is very much one tool we need to keep in our tool belts.

CURWOOD: By the way, you pointed out during the 1918, 1919 flu pandemic. One of the events a couple of the events are really set off the contagion were these rallies that were held around World War I. But the point of those rallies, the government was trying to raise money for bonds to pay for the war. In other words, there was economic interest in bringing people together at the same time, which makes maybe the public health interests would have been to keep them apart. What parallels, if any, do you see today from that kind of thinking?

The Dilruba is an ancient North Indian instrument which grew to become a family heirloom for Bina Venkataraman. In the book The Optimist’s Telescope Bina highlights ways of taking care of our earth and our natural resources by viewing them as family heirlooms. (Photo: Kasleen Kaur, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

VENKATARAMAN: I certainly see some parallels. So there's a hardship to small businesses to large businesses. When you decide to tell people to stay indoors, for example, and socially distance themselves, they're not going to go out and patronize the restaurants and bars and other places they normally would. There's an economic impact on canceling large events like the Boston Marathon, which was canceled this year or other events all around the world that had been canceled as a result of this outbreak. But we know also that acting early flattens the curve as epidemiologists like to say. Which is to say that at the peak of the epidemic, you're going to have less of a burden on healthcare systems and hospitals, you're going to have fewer deaths, you're going to have a faster recovery or return to normal if you spend Some of that burden on the system. Now, that requires some short term sacrifice to the economy at times, but what you're really doing is preventing damage to the economy over the long run. By reducing that health burden, it's hard to make decisions like that, because our politicians, our business leaders are often not rewarded for making the decision that turns out better in the long run.

CURWOOD: So let's talk about culture and thinking ahead. In particular, I'm wondering about Wall Street, which often focuses on the next quarter, compared to people who will erect cathedrals and it might be hundreds of years before the project as originally envisioned, finally, has the last stone put in place.

VENKATARAMAN: Yes, so you can contrast those cultures and really see a difference. And the question I wanted to ask IN writing the Optimist's Telescope was how do you bring some of the thinking of those cathedral builders into the context of very short term oriented cultures like an investment, like walls street it possible to do that? And one investment firm in particular that I write about in the book is Eagle Capital, which is based in New York and this firm, in particular, will look at milestones instead of near term metrics. So what is a company doing that is building its share of the market? What is a company doing that's increasing customer loyalty, and you can measure these things in different ways. They also just kind of try to map out scenarios for their investments. So they'll think a few years into the future 5, 10 years into the future and say, Okay, let's imagine the investment has failed, that this was a terrible investment. Let's ask ourselves why and how that happened, sort of in advance. This is a technique that Deborah Mitchell who was formerly at Wharton, called prospective hindsight, which is to say to project yourself into a future scenario as if it's already happened. And then ask yourself the why questions and how questions and that can help illuminate the decisions. We have Today that can influence those future outcomes.

In the Optimist’s Telescope Bina Venkataraman looks at mitigating losses caused by shortsightedness. (Photo: Courtesy of Bina Venkataraman)

CURWOOD: So how can we get to a better place thinking about the future, the way that we are compromising the habitat of this planet, whether it's with climate change or loss of species and such.

VENKATARAMAN: Well one interesting way of thinking about ourselves when it comes to the future that I really came to believe in, as I was writing this book, is to stop thinking of ourselves as sort of existing in our one chapter in time to rather think of ourselves more like ancestors. And when I was writing this book, I came across fishing communities in the Pacific coast of Mexico who is treating their lobster fishery in a way that I would say is kind of like a shared heirloom where they're trying to protect that lobster fishery overtime to pass to their sons and grandsons to continue fishing there. And, you know, there are other fisheries that are doing things like this that they may not consider to be thinking like ancestors or keeping heirlooms, but in practice kind of look like that. So there's a system being used known as cat shares for fisheries where the fisherman instead of just fishing as much as they can to get as much as they can possibly get out of a fishery, in the short run, become long term investors, and they have a share of that fishery, which grows over time if the fishery rebounds. So they have a motivation to bring back those fish populations so that their share can grow over time. And that's worked well with the commercial red snapper fishery for example, in the Gulf of Mexico that's run out of Galveston, Texas. So I found examples of places around the world communities where people are treating our natural resources, much more like shared heirlooms. And the question is, how do you do that? Well, you need rules you need either informal rules between communities that will establish what's worth taking now what's okay to take now, that will still leave, if you will, a sort of principle for the future, if you want to think of it as a fund, you want to still leave some capital in the fund and take off only what your generation should in terms of the interest from that fund, what should be used today. But when generations use and make meaning out of that heirloom, they in a way, become part of protecting it, and they adapt it and use it over time.

Bina Venkataraman served as Climate Change Innovation Advisor for the Obama White House and is the Editorial Page Editor for the Boston Globe. (Photo: Courtesy of Bina Venkataraman)

CURWOOD: I imagine a number of people listening to us are very concerned about the climate. Listeners, typically to living on earth have strong opinions one way or the other about it. And yet, I'm guessing that among the people who are listening to us that a significant number won't go to the polls and vote. Why do people have trouble thinking about the future when it comes time to get up and vote in ways that would help causes that they think are important?

VENKATARAMAN: Well, I hope this year, we're going to see a lot more people voting based on their concern from climate change. And actually, at the globe, we solicited questions when we interviewed Democratic presidential candidates. And I have to say that our readers seem to be very concerned about climate change, especially I think young voters, young people are really asking the question of what are the plans that our presidential candidates or our gubernatorial candidates have on climate change. Now, I think there's a reason that people can feel sort of powerless when it comes to climate change and part of it is that a lot of the way we talk about climate change a lot of the way the conversation in the media has been about climate change. So I'll take some responsibility for this, has been to paint sort of versions of the future that look pretty dismal. I think it's really important that we be very open-eyed about the threats that we face from a changing climate, but it's also important I think, for people to be able to imagine What does it look like if we can actually solve this problem? Is there a positive alternate version of the future that they can embrace that they can get behind so that they're not just voting against something when they go to vote about climate change, but they're voting for something. But I also think when people go to vote, whether they're young or old, wherever they live in the country, it's easy to let their present concerns dominate how they're going to vote. And I would say some of the tools and the Optimist's Telescope for projecting oneself in the future, whether that's writing a letter to your future grandchild, or child or niece or nephew, and just saying, what is the world that you want them to inhabit? Can you paint a picture of that world? I would love if everyone in the country just were focused on that next generation before they go to vote in November, for example, I think it could really change things. Because we are too often so focused on whatever that immediate need is and the way that politics works, the way that policy works, it's often the case that the impact Anyone election is going to be felt for generations.

CURWOOD Bina Venkataraman's new book is called The Optimist's Telescope: Thinking Ahead in a Reckless Age. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

VENKATARAMAN: Thank you so much, Steve.

Related links:

- Learn more about the author Bina Venkataraman

- Click here to read an excerpt of The Optimist’s Telescope: Thinking Ahead in a Reckless Age

- Learn more about social distancing in the 1918-1919 flu pandemic

[MUSIC: Oxymara, “Nathan” on Thundering Silence, by Michael DeLalla, Falling Mountain Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth