Warming Oceans And Toxic Shellfish

Air Date: Week of March 27, 2020

Environmental technician Andie Wall tests blue mussels and butter clams at a traditional harvesting site. (Photo: Courtesy of Andie Wall)

Many coastal native Alaskans rely on harvested shellfish as part of their subsistence lifestyle. But mussels and clams can carry a lethal dose of a toxic chemical called saxitoxin, and as ocean waters warm, the algae that produces that toxin is thriving year-round. Grist reporter Zoya Teirstein joins Host Steve Curwood to explain why the indigenous knowledge that has long protected coastal shellfishing from this threat can’t reckon with climatic changes.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The Alutiiq peoples of coastal Alaska rely heavily on fishing and harvesting for subsistence. And during the colder months of the year clams, mussels, and urchins are often on the menu. In fact, the Alutiiq has a saying – “when the tide is out, the dinner table is set.” But that way of life is being threatened by rising ocean temperatures, which are tied to an increase in saxitoxin, a poison that appears in shellfish, but which is completely colorless, odorless, and tasteless. Commercial shellfish beds are regularly tested for the toxin by state regulators, but recreational and subsistence ones are not.

And since a single clam can carry a lethal dose, while one next to it is completely safe, some now call the traditional subsistence lifestyle of the Alutiiq "Alaskan Roulette”. For more, I’m joined by Zoya Teirstein who reported this story for Grist. Zoya, welcome to Living on Earth!

TEIRSTEIN: Thank you for having me. I'm so happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So, give me a brief synopsis of this story and how it is that you came to investigate it.

TEIRSTEIN: The story is about climate change and how it affects people's lives from the very smallest things all the way up to the biggest. It's about Alaskan clams and shellfish really, and how tribes there, in a little town called Kodiak, are coping with the fallout of climate change, which is making their shellfish hauls toxic with this really kind of insidious toxin that can make you very ill and even kill you. I first found out about the poison itself, saxitoxin, at a conference in Woods Hole for science journalists. We had been hearing from researchers all day. And then finally this guy got up in front of us and he started talking about this algae. The algae are what carry this toxin, saxitoxin.

CURWOOD: So, Zoya, are we're talking about the red tide here?

TEIRSTEIN: No, not necessarily. Sometimes this toxic algae is present when there's a red tide. But it can also be there when there's no red tide.

CURWOOD: So, these toxic algae with the saxitoxin, what color is it?

Butter clams awaiting tests. (Photo: Zoya Teirstein, Grist)

TEIRSTEIN: Well, that's part of the problem. There is no color, there's no visible effect in the water. You can't tell if it's there or not. It's an invisible killer.

CURWOOD: So, let's say someone eats a clam or mussel that has the saxitoxin in it. What happens then? And what are the health consequences of this?

TEIRSTEIN: It really depends. People eat shellfish all the time in Alaska. And there's not necessarily any effect. However, if you bite into even just one clam, and this is what I opened the story that I wrote for Grist about, a woman who got sick when she was young and now no longer eats clams. If you bite into one that's very hot, that's very toxic. You can have some really serious effects. So what happened to her, her name is Phyllis Clough. She started getting numb in her mouth and lips, and sort of like a tingly sensation. It spread to the rest of her face. And luckily for her, she knew what to do, she, which is actually an indigenous technique, she made herself throw up. And that stopped her from feeling the full effects of the clam. People who are not so lucky can have a full-on lockdown. It's called paralytic shellfish poisoning for a reason, it paralyzes your system so your lungs can't breathe in air. And that's how deaths occur.

CURWOOD: Hmm. By the way, Zoya, have you eaten any clams after you've worked on this story?

TEIRSTEIN: No, I have not. What's important for me to note is that if you're eating clams or mussels in a restaurant, you're safe. This applies to recreationally fished shellfish. So for most people, that's not an issue. Most people I know are not going out in the morning and hunting for butter clams. But in Alaska, the average person pulls in 375 pounds of wild food a year. That's almost a pound per person per day, and close to 100% of the rural population in Alaska depends on foraging and hunting. And nearly half of those rural harvesters are Alaskan Native. It's a large number of people who are depending on this food to survive. So, basically, this issue affects them more than it would the average American.

CURWOOD: Now, I imagine this toxin has been in shellfish for as long as anyone could remember. So, in the past, how would people avoid this?

TEIRSTEIN: If you look at data from the past few decades, and it's limited, but it's there, thanks to the efforts of some very dogged researchers. There's a rule, it's the "R rule", people in the region follow it in order to stay safe. In months without an R in the name. It's not safe to hunt for shellfish. So we're talking May, June, July, August. Months with an R in the name are safe. And that's because those months are generally, or they have been generally, colder. And during cold months, that algae that are toxic don't thrive, it hibernates on the ocean floor mostly in hard little cysts.

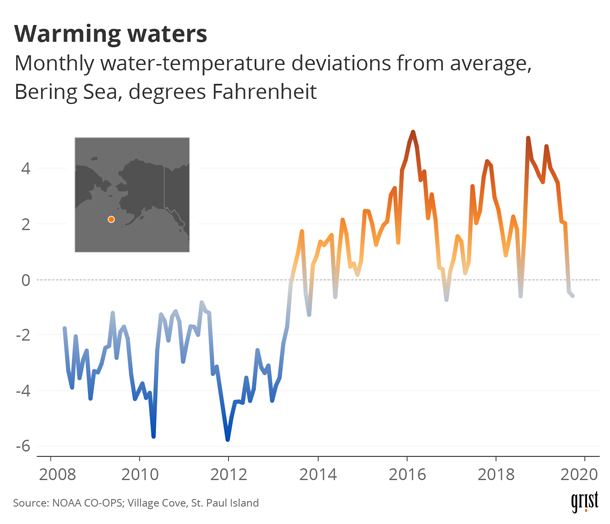

This graph examines the monthly water-temperature deviations from average in the Bering Sea, where Kodiak Island is located. (Photo: Clayton Aldern, Grist)

CURWOOD: And just to be clear, even though it's not ever a perfect measure of safe shellfish, it was more or less considered, well, least relatively safe to eat in those months with the "R", is that correct?

TEIRSTEIN: Yeah, exactly. Many people ate during that time and still do.

CURWOOD: So, the old saying that you can eat shellfish during any month that has an R in it, to what extent has the lengthening summer or the shorter winter, however you want to put it, changed that way of guarding against toxic shellfish?

TEIRSTEIN: So, what's happened with climate change and with warming ocean waters and warming shoulder seasons, we're talking April, and then October, sort of the spring and fall, is that all those rules that people lived by and stayed relatively safe with, although people still have died in Alaska for years and years, those rules no longer work at all. As the ocean warms, that algae are prevalent year-round. Clams are toxic year-round, even in the dead of winter is what one researcher told me in Kodiak. So, the danger there is that people go to the beaches to harvest following that one rule, the "R rule" in April, for example, it's a month with an R in the name, and they haul in a catch that's really, really toxic.

CURWOOD: Some might say, well, people should just avoid eating shellfish. What do you say to someone who suggests that diet for this community, which has this as important subsistence food,

TEIRSTEIN: I've heard that a lot in the course of my reporting, mostly from folks who have never been to Alaska or don't understand the importance of shellfish for the communities there, particularly for Native communities, a quarter of whom live under the poverty line. So, for many folks up there, subsistence fishing and harvesting is a main source of food; without it, people go hungry. I had one person tell me that growing up, all the Native kids in his village knew where to find butter clams and mussels. And if you didn't know where to find them, you'd starve. So, it's really sort of a matter of life and death for a lot of people. And not fishing is just not an option. So, what you'll see is that people are fishing up there and harvesting clams and mussels and other shellfish, even when researchers tell them not to, please don't, don't go to the beaches, it's not safe, you could die. And you see people disregarding that because they simply have no other choice.

CURWOOD: So, if warming temperatures increased the frequency of toxic shellfish, what kind of impact might that have on Native Alaskans?

Phyllis Clough (left), her brother, Sven Haakanson, and her mother, Mary Haakanson are part of Alaska’s Alutiiq tribe. Phyllis once ate a toxic clam and suffered from Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning. (Photo: Courtesy of Sven Haakanson)

TEIRSTEIN: That's the thing, we don't quite know the scope of the damage or the foreseeable damage yet. Part of the problem is that there is no system in place, both for monitoring shellfish on the coastlines and for keeping track of people who have gotten sick. If you get sick with PSP or other algae borne illness, you have to call it into the state's Department of Health. A lot of people don't know what that number is, they don't know they have to report it. The symptoms can be commonly confused for the flu, or even for a heart attack if you eat enough of the toxin. So, really, the numbers the state has on file for how many people have gotten sick are not at all indicative of the scope of the issue. What one state official told me was that it's just the tip of the iceberg. There's definitely a lot more cases that aren't reported to the state. So really, right now, researchers are scrambling to create some sort of safety net for people who might get sick. They're trying to protect the community at all costs. There's not enough of them, there are not enough resources to go around. So, people will probably get sick and they will likely die.

CURWOOD: So, what about this problem is unique to Alaska? I mean, why doesn't the rest of the country have to worry so much about paralytic shellfish poisoning?

TEIRSTEIN: Every other coastal state in the nation has a system in place to protect its subsistence fishers. Here in Washington state, where I am, you can go to the beach and you'll see signs. Either it's closed or under advisory or it's open for shellfishing. They test the water there really frequently and they test the shellfish, so you can go to the beach and feel some level of safety about what you're going to do. In Alaska, there's no system like that. So, that's why it's a large problem there for people who want to subsistence harvest.

CURWOOD: And what do people tell you is a solution here?

TEIRSTEIN: Well, that's the tricky part. The solution, as far as I can tell, is very much homegrown. In Kodiak, where I was reporting the story, a band of researchers and volunteers and Alutiiq folks and the Sun'aq, which is another tribe native to the area, have banded together to create a system, so they test the beaches that are commonly fished at and they try and arm the community with the facts they need to harvest safely. The problem is that it's not a well-funded system. It depends on whether the researchers are available that day. If someone gets sick you lose a day of data. So, it's definitely not the same kind of system that other states have.

CURWOOD: Zoya Teirstein is a reporter at Grist. Zoya, thank you for your time today.

TEIRSTEIN: Thank you.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth