June 1, 2018

Air Date: June 1, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Half a Degree Hotter Will Cost $30 Trillion

View the page for this story

The most ambitious target of the Paris Climate Agreement is to limit global warming to one and a half degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, rather than two degrees. Now researchers at Stanford University find that avoiding a half a degree of additional warming could save a whopping $30 trillion of GDP globally. Marshall Burke, an Assistant Professor of Earth System Science who led the study, explained to host Steve Curwood how saving global heat could save trillions. (08:33)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and Steve Curwood take a look beyond the headlines at a tree-sitting Appalachian pipeline protest, and discuss Forest Service workers who are taking construction lessons from beavers. From the history books, Steve and Peter review the convictions of Union Carbide executives for their role in the Bhopal, India chemical plant disaster that killed thousands, and note the CEO and other company officials avoided serving time. (04:02)

A Record Hurricane Disaster in Puerto Rico

View the page for this story

The Puerto Rican government's estimate of 64 deaths from Hurricanes Irma and Maria struck researchers from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health as too low, so they decided to investigate. The team’s door to door survey revealed that the death toll was on the scale of thousands. At least 800, and as many as 8,000 if not more, perished as a result of the hurricanes' destruction and interruption of the power grid, water infrastructure and medical services, making it the worst natural disaster in the US in more than a century. Host Steve Curwood sat down with senior authors emergency medicine physician Satchit Balsari and epidemiologist Caroline Buckee to learn why their survey is such an important tool, and how it can spur preparedness in the future. (18:35)

Final Generation for the Marshall Islands?

View the page for this story

The coral atolls and islets of the Marshall Islands rise no more than six feet above sea level, and face acute problems from sea level rise linked to climate change. A new interactive documentary film titled, The Last Generation, looks at the crisis in the Marshall Islands from the perspective of three children who understand the perils and uncertain future they face living there. Host Steve Curwood talks with reporter Katie Worth who helped put the documentary together for Frontline PBS, and the GroundTruth Project. (10:59)

Nooks for Nesting

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

A single garden can provide havens for a medley of bird species, because they choose different strata of shelter from tall trees to low bushes to raise their nestlings. Mary McCann heads to the backyard in today’s BirdNote®. (02:05)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Marshall Burke, Caroline Buckee, Satchit Balsari, Katie Worth

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Sixty-four – that’s the official death toll for the 2017 hurricanes in Puerto Rico, but a new analysis from Harvard indicates that many more died – from 800 to 8000 – maybe even more.

BUCKEE: I think the key takeaway here is that the morality rate was increased, and it stayed high throughout the rest of the year.

BALSARI: When we think about disasters, disaster response planning, we think of an acute event, a whole bunch of people die, and then life goes on. Well, that is not what we are observing in disasters now and certainly not in Puerto Rico.

CURWOOD: Also, the South Pacific can be paradise, but not for children in the path of rising seas.

WILMER: I think when the Marshall Islands will be gone, it’s like the end of life to me, like the end of the world. Imagining that, it’s very horrifying.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Half a Degree Hotter Will Cost $30 Trillion

An economic analysis finds that the benefits of meeting the most stringent targets set out by the Paris Climate Accord far outweigh the costs. Meeting those targets will require a rapid transition towards more renewable energy sources, such as wind and the development and deployment of ways to extract greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. (Photo: Karsten Würth, Unsplash Creative Commons)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Back in 2015, the Paris Climate Agreement set two goals: Parties agreed that planet warming should in no event be allowed to exceed two degrees centigrade above pre-industrial levels, but it would be better to limit the warming to one and half degrees. At this point the pledges made by individual countries so far will not achieve either goal, but a team based at Stanford University has calculated that the less warming in that half degree of difference could be worth 30 trillion dollars in the world economy. They found that almost all nations would economically benefit from tighter restriction of temperatures and saving the 30 trillion would cost less than a half a trillion. Marshall Burke is an Assistant Professor of Earth System Science at Stanford University who led the study. Welcome to Living on Earth!

BURKE: Thanks a lot for having me.

CURWOOD: So, your research says that it will cost the world some 30 trillion dollars more if we go from one and a half degrees Centigrade to two degrees Centigrade in global warming. Where would that money come from? Who would be charged that 30 trillion dollars?

BURKE: So, the 30 trillion dollar number we have is a global total. So, this is adding up the sort of additional losses we would suffer at two degrees instead of 1.5 degrees around the world. So, think of this as a global number, but importantly we find that these sort of costs, if you will, or benefits – if you – if you want to think about it in terms of staying at 1.5 degrees Celsius – we find that these benefits are unequally distributed. So we find that the largest benefits at least in percentage terms will be in the poorest parts of the world, countries that are already very hot and for whom any additional warming exacts a lot of additional economic damage. So, we find that the benefits will be largest in the tropics.

CURWOOD: So, Marshall, explain that to me. Why will these poor, tropical countries get hit harder? Don't they have less infrastructure?

BURKE: Yeah, so our study is based on a historical understanding of how economies in the past have responded to changes in temperature. So, we have a half-century of data from countries around the world that measure economic output at an annual level. And what we do is we use those data to understand, Okay, historically when the temperature has gone up by a degree Celsius, how much has economic output changed? And what we find when we do that is, if you're a cold country, and you warm up the temperature a little bit, these countries often do a little bit better. You can see this very clearly, for instance, in the Icelandic data. Iceland is a really cold place. If you crank up the temperature a little bit in Iceland, historically Iceland does better in terms of economic output. Now, the opposite is true in hot countries. These countries are already quite hot, and as you crank up the temperature we see large economy-wide impacts of higher than normal temperatures.

Warming from greenhouse gas emissions could make the entire world 10% poorer by the end of the century if it continues at current levels. (Photo: Daniel Lerps, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Your study is mainly GDP-focused, and you don't look at specific sectors. But give us some idea of the sectors that would be really hit hard by this increment in warming.

BURKE: Yeah, our study focuses on total economic output, so GDP, Gross Domestic Product, which is just the value of all the stuff that's produced in a country in a given year. But you're right that we might think that changes in climate would affect different sectors differently. Our study doesn't look at that directly, but a sort of a host of other research looks at this.

So, we know that agricultural productivity suffers when it's hot and so this is one reason why it's probably true that poor countries suffer more when the temperature goes up. They're largely dependent on agriculture, and so any losses in agriculture are sort of magnified for them. But the impacts extend, we think, far beyond agriculture, so there's lots of work now showing that even labor productivity in high tech manufacturing suffers when the temperature is higher. We see lower cognitive performance when the temperature is higher. So, kids taking standardized tests do worse when the temperature is hotter on the day of the test, right? So, we see overall declines in cognitive function, and so, these likely have influence on many factors that you know, again, are far beyond agriculture.

CURWOOD: So, you say places like Iceland maybe Russia, Canada, fairly cold places might actually see a little more economic progress with a bit more warming. Can you explain that for us?

BURKE: Yeah, that's right. I think it's easy to start intuitively. So, just think about how comfortable we are at different temperatures as humans, right? We're very comfortable in sort of mild temperatures. We're quite uncomfortable at really cold temperatures and really hot temperatures, right? And so you can imagine if you're in a really cold place, and you warm up the temperature a bit, we're more comfortable and we’re likely more productive. And it turns out, that shows up really clearly in the GDP data of these countries.

CURWOOD: So, you suggest that if we could keep global warming to just one and a half Centigrade, the world would save some 30 trillion dollars between now and the end of the century. What would it cost to save those 30 trillion dollars?

BURKE: That's right. So, our study focuses on the benefits, the economic benefits, of reducing warming basically, of keeping warming at 1.5 degrees versus two degrees Celsius. But you have to weigh that against the costs of meeting these more stringent mitigation targets. So, other folks have tried to calculate the cost, right? What would be the differential cost in terms of how much money do we have to spend to transition our energy sector away from dirty fuels to cleaner fuels, for instance? So, what would be the total economic cost around the world? And the estimates that other folks have come up with are on the order of half a trillion dollars. And so that is basically an order of magnitude lower than what we calculate the benefits to be of undertaking those actions. So, to us, the cost benefit calculation looks wildly favorable for stronger mitigation.

CURWOOD: So, Marshall, one thing that really concerns me about your study is one could argue that it's going to be very tough to hit one and a half degrees Centigrade warming, to limit it to that, given what is going on right now among all these countries that have agreed to the Paris Climate Agreement, not even thinking about the United States which is trying to get out of it. I mean, what are the odds of us being able to achieve these savings that you say that we would have if we could achieve that?

Marshall Burke is an Assistant Professor of Earth System Science at Stanford University. (Photo: courtesy of Marshall Burke)

BURKE: So, the odds of achieving the 1.5 C. target right now are pretty low, and doing so depends on us inventing carbon capture technologies that do not yet exist and deploying those technologies sort of massively such that by mid-century we're actually pulling more carbon out of the atmosphere than we're putting into the atmosphere. So, we need to go sort of net negative in emissions terms by mid-century. So, the optimist in me wants to believe that we can get there and perhaps numbers like ours would suggest that the economic returns of getting there are higher than we thought, but you're right that we are certainly not on path right now to meet these more stringent goals.

But I think bigger picture, what our estimates suggest that any effort we put in to reduce warming is likely to generate large economic benefits around the world. So, right now are headed for three degrees Celsius. If we can keep it below that that's going to generate benefits, if we can go all the way to two, that generates even more benefits. So, what our results again suggest is that there are large benefits from even relatively modest reductions in future warming.

CURWOOD: Some people listening to us would say, “Okay, this is interesting, but how do you put a price on some of the things that are likely to happen in the years ahead if we don't hit this one and a half degree Celsius target?” In this broadcast there is a segment about kids living in the Marshall Islands looking ahead at their future, and at two or three degrees C they have no homeland. Their Marshall Islands are going to be underwater as are a number of other low-lying places. How do you put a price on losing the places that people can live?

BURKE: That's a great question and that is not something that our current approach grapples with very well. So, all we are able to measure in this approach is things that show up in gross domestic product. So, again they’re just the value of the goods and services that are produced in an economy in a year. So, we will not capture many of these other very important things – loss of homeland, loss of habitat, that we know to be very important, that we imagine will likely be fundamentally affected in the future, but things that do not show up in this measure of GDP. So, to the extent that we think those things are important and that they could be negatively affected by future warming, then they won't be included in our estimates and our estimates will be an underestimate of the impacts of more warming in the future.

CURWOOD: Marshall Burke is an Assistant Professor of Earth System Science at Stanford University. His paper was published recently in "Nature." Thanks so much, Professor, for taking the time.

BURKE: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- The Guardian: “Hitting toughest climate target will save world $30 tn in damages, analysis shows"

- The study in Nature: “Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets”

[MUSIC: Jason Marsalis, “Treasure” on Music In Motion, Basin Street Records]

Beyond The Headlines

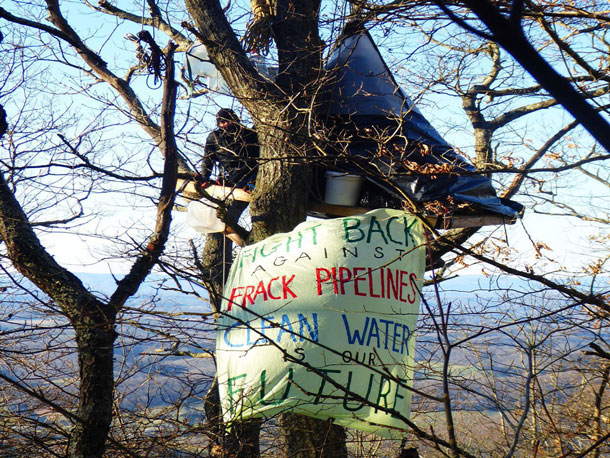

Tree sitters in Appalachia protest the Mountain Valley Pipeline. (Photo: Capital News Service, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: There’s plenty of news beyond the headlines these days and our guide is Peter Dykstra. He’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org, on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, what’s going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve! Let’s go to the Appalachians, the border of Virginia and West Virginia. There are tree-sitters, some of whom have been up for as many as fifty days, trying to stop construction of the Mountain Valley natural gas pipeline.

CURWOOD: Wow! What’s their objection?

DYKSTRA: Their objections are many, one of which is that pipelines tend to break or spill and can threaten ecosystems. This being their home, they’re a little worried about that. They’re also a little resentful, if you will, that the company that owns the Mountain Valley natural gas pipeline actually started clear-cutting and preparing for the site before they had any permits, suggesting that the political process to build a pipeline may be a little bit rigged.

CURWOOD: Hey Peter, I’m old enough to remember and I think you are, the Redwood Summer, and then Julia Butterfly Hill when she sat for – how long in a tree?

Forest Service workers are replicating natural beaver dams like this one in order to restore habitats along the Rio Cebolla. (Photo: J.N. Stuart, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well I’m old enough to forget a lot of things, but I definitely remember that one. There was first the Redwood Summer and then Julia Butterfly Hill, who was an activist, from December 1997 to December 1999 – a full two years – who sat in a redwood tree in Northern California to prevent logging in an old growth redwood forest.

CURWOOD: Yes, I believe her tree was named, “Luna.”

DYKSTRA: Correct.

CURWOOD: Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Next stop is New Mexico. The Rio Cebolla is an ecosystem that’s being degraded partly because cattle grazing and other things. There are workers from the US Forest Service and some volunteers who have been out building the human equivalent of beaver dams to restore the ecosystem. They’re basically imitating beavers.

CURWOOD: Huh, so why?

DYKSTRA: Beaver dams built by humans! Wildlife and fish, they say, are beginning to thrive. They’ve done 24 of the beaver dams this year with plans to do more. They create deeper water pools and more natural wetlands.

CURWOOD: There’s got to be a catch.

DYKSTRA: Well, here’s a little irony. There’s still cattle grazing there, so they have to worry about that for further degradation, but as they plant willow trees and build beaver dams to help restore this ecosystem, one of the other threats to that are real beavers who will move in before the restoration is complete.

Inside the Union Carbide pesticide factory in Bhopal, India shortly after a chemical disaster there killed thousands of people in 1984. (Photo: Bhopal Medical Appeal, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Huh, well maybe they’ll sue for intellectual property rights as well! Hey time to turn to the history vaults, what do we have today?

DYKSTRA: A lot of people will also remember that in 1984, one of the worst chemical accidents in human history in Bhopal, India, killed thousands when a chemical called methyl isocyanate leaked in a fairly large city. And in June 2010, eight years ago, eight executives from the owners of the plant, Union Carbide, were convicted in absentia of negligence in this huge death toll.

CURWOOD: By the way, I think there’s an identical plant to Bhopal in Institute, West Virginia that’s still operating today.

DYKSTRA: That’s right. And Carbide eventually sold out of the plant in Bhopal, but not before eight of its executives were convicted. If they ever showed up for sentencing they would have faced only two years and two thousand dollar fine. A half a million people were affected by the gas leak in Bhopal. The government confirmed 3,800 deaths. Those numbers are almost universally dismissed as being too low. There are other estimates that say 8,000 and maybe as high as 16,000 died as a result of the Bhopal disaster. Warren Anderson, the CEO and chair of Union Carbide at the time, was declared a fugitive from justice. He died here in the US in 2014.

CURWOOD: Without serving a day.

DYKSTRA: No.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter, we’ll talk to you again real soon!

DYKSTRA: Okay Steve, thanks a lot! Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And you can find more on these stories on our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Guardian: “America’s tree sitters risk lives on the front line”

- Santa Fe New Mexican: “Man-made beaver-style dams help restore land in New Mexico”

- The New York Times: “Warren Anderson, 92, Dies; Faced India Plant Disaster”

[MUSIC: Wynton Marsalis, “Embraceable you” Wynton Marsalis septet at Dizzy’s Club

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P1dkHuxWI_w]

CURWOOD: Getting the math right for the Hurricane disaster in Puerto Rico. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Glen Velez, “Pan Eros” on Pan Eros, CMP Records]

A Record Hurricane Disaster in Puerto Rico

On Oct. 6, 2017, more than two weeks after Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico, U.S. Navy rescue personnel transfer a patient to the hospital ship USNS Comfort (via helicopter). (Photo: U.S. Navy Photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Ernest R. Scott/Released, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Hurricanes Irma and Maria devastated Puerto Rico when they hit the island last September, and as hurricane season begins again, power is still not fully restored and infrastructure remains fragile. But official figures claimed that the death toll was modest – that a mere 64 people had died as a result of the disaster. Well, now a team led by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health has made a new calculation of mortality related to the hurricanes, and the new figure shows the official estimates to be a startling undercount. We’re joined now by two of the senior authors – team leader and epidemiologist Caroline Buckee, and emergency room physician Satchit Balsari – welcome to Living on Earth!

BALSARI: Thank you for having us.

BUCKEE: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Caroline, what was the genesis of this? What was the idea that generated this study?

BUCKEE: After Hurricane Maria, it was clear and, in fact, the government acknowledged that there should be some reevaluation of the death count in the wake of the hurricane because the official estimate was 64 deaths due to the hurricane. And in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria it was clear that there was a ton of infrastructure damage and that, in fact, this was probably an underestimate. In the wake of disasters it’s very hard actually to estimate mortality because when infrastructure is so damaged issuing death certificates is difficult and normal health systems are not functioning well.

And so one of the ways that you can provide an independent estimate of mortality in the wake of disasters is to go and do a household survey study like the one that we did. And what that means is that you are providing an estimate that is not dependent on the death registry system or on death certificate issuance. And so you can capture deaths as well as well as other nuances like infrastructure damage, loss of utilities like electricity and water, as well as other types of suffering. So, what the reported causes of death were according to family members.

CURWOOD: Satchit, why did you get involved in this project?

BALSARI: Well here at the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, we have routinely worked with vulnerable populations to leverage science, big data, for human rights advocacy. So, these kinds of situations are situations that our scientists are very familiar with and very comfortable working in. I've been a student of disaster medicine and humanitarian crises for the past 20 years and I work closely with Professor Jennifer Leaning, and we felt when Caroline reached out that this was another excellent opportunity for us to leverage the experience that we had elsewhere to advocate for the people in Puerto Rico.

CURWOOD: Caroline, as I understand it your study came up with some 4,600 excess deaths from the storm – actually the storms I should say, right? Because this covers a longer period of time. Just what was your method there to come up with the numbers?

BUCKEE: So, before I describe the method, I think it's very, very important, and we've seen in the last few days, the importance of emphasizing that this is not a precise estimate. So, there are very large confidence intervals around this estimate. And so the range of the 95 percent confidence intervals is from about 800 to over 8,000, and the estimate as it stands came out as 4,645, but it's misleading to quote that as a number because it’s, by definition, it’s not a precise number. And that's because of the methodology.

So, we used a survey approach where we randomized households across Puerto Rico and then we went door to door and we are asked members of that household to tell us about their families. What the composition of the household was, how old the people were, the genders, if people had died, what they had died of and when they died, as well as asking about displacement, so who had moved into the house, who had left the house during that time period. And then we asked about utilities, so how long had you been without electricity or water or cellular telephone coverage.

So we surveyed 3,299 households which covers a population of approximately nine and a half thousand people, and from that we could calculate a mortality rate. And we compared that mortality rate to the same period of time in Puerto Rico from 2016. So over that period of time from September 20 to December 31, we compared the mortality rates and the rate difference tells you about how many excess deaths occurred. And then from that rate difference we multiplied it up to cover the whole population. And so there's a large amount of uncertainty associated with that calculation because there are many different ways to estimate the population size of Puerto Rico in the aftermath of the hurricane, and we used a fairly low number to account for the fact that we know people left the island leading up to the hurricane, and so we wanted to make sure that we were conservative with our estimate.

Nevertheless, it is very uncertain. And the key point here is that this approach does not rely on infrastructure. It's very quick, it's very cheap, and if the government wanted to employ this type of approach in the future when their death registry system was not working well, it would be straightforward to implement a much larger survey and then they could make the estimate much more precise. So, I think the key takeaway here is that the precise number is less important than the fact that the mortality rate was increased and it stayed high throughout the rest of the year.

CURWOOD: By the way, for people who aren't scientists, they might say "excess deaths? I mean, any death feels very personal.” What's the scientific meaning of "excess death?"

BUCKEE: So, essentially we always expect some level of frequency of deaths in a population. People die. And so we're talking about deaths over and above what we would normally expect in that period of time. So, that's what we're trying to calculate: the difference between what would normally happen and what we observed due to the hurricane.

Hurricane Maria tore across Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017, swamping towns both inland and at the coast with floodwaters and storm surges, and turning the island’s lush green landscape brown from damaged vegetation and mud and debris deposits. (Photos: NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey)

CURWOOD: It’s interesting, though, that your numbers, if it's a range between 800 and, say, 8,000, still the government was talking about 64. So, even the low end of what you're talking about is quite a bit larger than what has been officially acknowledged.

BUCKEE: Absolutely, and interestingly our results are consistent with several reports – a few academic reports and in the press – that came out after the hurricane. And so out of those handful of studies, the only outlier is the government estimate of 64. And in fact, the government does acknowledge that that is an underestimate, and that's why they have issued this reevaluation of the death registry data.

CURWOOD: Satchit, so how has the government of Puerto Rico responded to your research?

BALSARI: The Governor of Puerto Rico in a press conference hours after the paper was published welcomed the research. He said he was looking forward to learning more. We have reached out to his offices and offered to be available to sit down and explain our findings to the officers.

CURWOOD: Now, you're an emergency physician. I know that your research didn't look at death certificates. So, you don't have causes of death per se, but what do you think happened to these people who perished?

BALSARI: Well, while we did not look at death certificates, we did ask people what their family members died from. We also asked people what they had continued to suffer from, the interruption in services. And what we find are a few different things. As Caroline explained, the persistence of the elevated mortality rate is what is of concern. When we think about disasters, disaster response planning, we think of an acute event, a whole bunch of people die, and then life goes on.

Well, that is not what we're observing in disasters now and certainly not in Puerto Rico. There was interruption of basic utilities for a long period of time. Large groups of populations did not have access to water, cellular phone coverage, and electricity for a good amount of time. One third of all those that had died in the households that we had surveyed attributed those deaths to interruption of medical care. There's a variety of reasons that people provided including broken down roads: disruption in the health care facilities themselves, and availability of doctors, difficulty accessing medications. Then not being able to use their respiratory machines, for example; nebulizers or CPAPs that people used at home, or dialysis machines that they went to their clinics for.

This phenomenon of interrupted medical care is important for responders in the United States to pay attention to. We have seen that all the way back in Hurricane Katrina. We continued to see that in Sandy. Nursing homes are affected. The elderly are dependent on life-sustaining equipment that is electricity-dependent. Even the evacuation of hospitals in Sandy was because the generators flooded and failed and patients had to move. It is that same phenomenon that we're seeing play out in Puerto Rico, but not just on the days of the event, but for months thereafter.

CURWOOD: So, take a step back for a moment. We're in a period of time of a disrupted climate and there are likely to be more very serious storms that hit Puerto Rico. I mean just this past year we saw Houston, we saw Florida, we saw Puerto Rico … oh, and out west we saw a whole bunch of fires. What does your research tell us we should be thinking about, acting about, going forward as a society as we deal with the pressures of climate disruption?

BALSARI: We should map our vulnerabilities better. That is not just the role of the government, but community preparedness is really the key to all our societies faring better with these disasters. It is important to know where the uncles and aunts that are on dialysis, who is on breathing machines, what equipment is your neighbor dependent on. Even high resource populations that think they're otherwise insulated from disruptions and climate change are very much vulnerable. Think about the elderly that lived in high rises in downtown Manhattan after Hurricane Sandy. This was a rich population, normally used to all kinds of services, that were trapped without food, water, electricity, and access to medicines on the 30th story and the 40th story of high buildings. Again, the California bushfires and the demographic that was affected. So no one, no one is spared from the impact of these adverse climate events that we are observing.

Most of Puerto Rico’s electric power grid and telecommunications network was knocked offline when Hurricane Maria tore across the island, as shown in this NASA satellite image – and for many, it stayed offline for months. (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data courtesy of Miguel Román, NASA GSFC, and Andrew Molthan, NASA MSFC)

CURWOOD: I gather that this research was conducted over a very short period of time. It just took you a couple of months to do the interviews and then crunch the numbers. How do you feel about that, and how do you feel about the response that the public has had to this?

BUCKEE: So, the quick turnaround of this study and the ability to do it within – we completed the surveys within three or four weeks, and the analysis took another couple of weeks. So, this was a very quick assessment, and we had a small budget and we were constrained in the sample size as a result. So, 3,299 households was a lot, but since deaths are rare events, even after the hurricane, that means that our estimate is imprecise. So, although overwhelmingly the response has been positive and people have welcomed some insights, and I think they’ve welcomed the fact that we've made the data freely available online for anyone who wants to analyze it, there is some pushback about the uncertainty of our estimate. And I think one of the challenges here is communicating scientific uncertainty to the public. This is a really important part of our job, and I think we probably don't do it very well. It's very important that we continue to state that this was a small survey, the uncertainty was large, it doesn't invalidate the fact that we find significantly higher mortality.

BALSARI: Household-based surveys are fairly standard, so the innovation here was not that we did a household-based survey. For decades, the scientific literature has deliberated on how best to do these household surveys and how they complement death registry data and other forms of accounting for deaths after disasters. So, while the response has been overwhelming, we hope that it complements any future endeavors that the government undertakes to establish both accuracy of the death toll, but also to support closure for these families.

Going into the hurricane season, we are hoping – and the Governor said so – that they will relook at how deaths are counted in the aftermath of disasters. And what Puerto Rico comes up with could potentially help the rest of the country as well. In the United States, currently, a death is attributed to a disaster event if it is noted on the death certificate, but the criteria for noting death on a death certificate is not known to most. There are very few people that are trained in understanding that even in the days following a disaster there are several indirect causes of death that can be attributed to the event and that this has to be noted on the death certificate. So, we do need expanded training and awareness of how these deaths have to be recorded appropriately so that they can be counted.

CURWOOD: In other words, you're saying if somebody couldn't get to their, say, cardiac medication for several days and they had a heart attack – if they write “heart attack” on the death certificate, and they don't attribute it to the fact that the streets were flooded, that they're missing something.

BALSARI: Precisely.

CURWOOD: How does your study help with closure from such a disaster?

BALSARI: Well, I think it is important for deaths from disasters to be acknowledged. It is certainly important to families. They want to know that society knows why they lost their beloved. It also has financial ramifications. People have access to aid assistance from FEMA, from other government agencies, if they have lost someone in a disaster. It is important that that be recognized and that the families be given access to the aid that they deserve.

CURWOOD: Why do you suppose that the government got this so wrong, the scale of the loss of life in Puerto Rico?

BALSARI: The numbers that the government declared were numbers that they were working with. It is how deaths were being counted in the early days after the disaster. I think the failure was in recognizing that the official methodology for counting death was highly flawed. And had they looked around and gathered data from multiple sources outside of just the death registry data, they might have been working with very different information.

CURWOOD: I mean, you guys took – what? – less than two months to do this. Why didn't Puerto Rico, why didn't the Federal Emergency Management Agency? Why didn't they trot out this more sophisticated math themselves?

BUCKEE: Well, currently this type of approach has been largely an academic exercise in the wake of disasters, and in fact, this has been occurring in studies since the 1970s to try and estimate the impact on the population. And as it stands now, the way that the government counts deaths is through death registries, and it does not use these additional sources of information. So, what we're advocating is to have a shift where we do start to see these types of studies being done by the government as well. And we hope that it will become more standard. At the moment these are largely scientific exercises undertaken by academics rather than by the government itself.

CURWOOD: Academic exercises – and yet your study’s on the front pages of many newspapers and many national broadcasts.

BUCKEE: That's true. The fact that the government has acknowledged from very early on that they needed to reevaluate the number of deaths attributed to the hurricane – and the fact that they have commissioned George Washington University to go through all of the death registry data again which will take some time – it shows that they are aware that there are limitations. The infrastructure damage in Puerto Rico after the hurricane was enormous, and they were dealing with all kinds of other priorities at the same time as trying to keep track of mortality. And so, you know, that is a huge challenge and it remains a huge challenge. And so moving forward, I think the most important thing is that we can complement activities when infrastructure is destroyed with these quite simple approaches, which are quick and can be done in a simple and transparent way.

CURWOOD: You know famously, Heisenberg the researcher said anything you measure you're going to affect. How did doing this research in Puerto Rico affect you?

BALSARI: Profoundly … I think these kinds of projects or spending time in these environments is a constant reminder of how lucky the rest of us are.

BUCKEE: Yeah, it was very affecting, and of course my heart goes out to all of the people who suffered in the wake of Hurricane Maria. But I was also quite hopeful in some ways because the students that we worked with who conducted the surveys, these were graduate students in psychology from Carlos Albizu University and Ponce Health Sciences University. They were utterly dedicated, very bright, they worked so hard round the clock to get these surveys done, and they have been working on their own time with the communities, supporting communities who have suffered so much from day one after the hurricane, and their energy and dedication, I felt was really a hopeful thing. And so while, you know, the devastation has been enormous to the island, I do think that there is hope because the Puerto Ricans we worked with were just so resilient and hardworking and determined, and so that gave me some small hope.

CURWOOD: Caroline Buckee and Satchit Balsari are with Harvard University's T.H. Chan School of Public Health and authors of the study of Puerto Rican mortality. Thank you both for taking the time with us today.

BALSARI: Thank you for having us.

BUCKEE: Thank you so much.

Related links:

- The New England Journal of Medicine: “Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria”

- FEMA has a June 18th 2018 deadline for disaster relief from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico

- The Puerto Rican government held a Disaster Preparedness and Management Convention at the start of the 2018 hurricane season

- The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

- The Harvard FXB Center for Health and Human Rights

CURWOOD: You can hear our program any time on our website, or get an audio download. The address is LOE dot org. That's LOE dot O-R-G. There you’ll also find pictures and more information about our stories.

And we’d like to hear from you: You can reach us at comments @ loe dot org.

Once again, comments @ l-o-e dot O-R-G. Our postal address is PO Box 990007, Boston, Massachusetts, 02199. And you can call our listener line any time, at 617-287-4121. That's 617-287-41-21.

[MUSIC: Jacqueline Schwab, “Bright Morning Stars Are Rising” on Down Came an Angel, traditional Appalachian, Dorian Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, A boy dreams of becoming president of a land that may not be there when he comes of age. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies – combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Marian McPartland’s Hickory House Trio, “Tickle Toe”]

Final Generation for the Marshall Islands?

Nine year old Izerman. (Photo: The Last Generation)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC FROM FILM SOUNDTRACK AND CRASHING WAVES]

CURWOOD: The vast Pacific Ocean surrounds the coral atolls that make up the former US territory of the Marshall Islands, and the Marshalls typify the vulnerabilities of low-lying lands facing climate disruption. The GroundTruth Project and Frontline PBS have produced an online, interactive documentary titled “The Last Generation” that reveals the realities of rising seas through the eyes of three young residents.

JULIA: I was sitting on the sea wall. I didn’t see the wave coming. It just pushed me off and I thought it was something else than a wave. I thought it was like a monster.

IZERMAN: My grandmother told me to come to the church. So I ran here and sit, watching everybody yelling, watching the babies crying. And it was not good.

WILMER: My mom woke me in the middle of the night. When I woke up I saw a lot of water. It was around my knees. People were evacuating very quickly. I wasn’t scared but I was shocked. In that moment I started talking to myself. Is this king tide happening because we are bad people?

CURWOOD: These are not rare occurrences in the Marshall Islands. Reporter Katie Worth of Frontline PBS worked on the documentary.

WORTH: The Marshall Islands is an archipelago of very, very low lying islands in the middle of the Pacific. Its capital, Majuro, where we were sits at an average of five feet eleven inches above sea level, which makes it one of the most vulnerable places on Earth to sea level rise. And it's already happening there. There's evidence that's showing that floods are already on the rise, there are more droughts. A recently study funded by the Department of Defense showed that with just about 15 inches more of sea level rise, islands like Majuro will be devastated by floods on an annual basis.

CURWOOD: Now your documentary looks at the Marshall Islands and the flooding risks there from the perspective of three different children. Why tell the story through kids?

WORTH: Climate change is one of those stories that people tend to turn the page on, and we wanted to make a story that would be hard to turn the page on, and that you want to lean forward on and learn about, and we wanted it to be compelling. My reporting partner Michelle Meisner had read somewhere that kids from the Marshall Islands can tell you all about climate change, and that intrigued us. So, what would they tell us? How well do they really understand? How do they think about their futures on this island that literally may no longer exist within their lifetime?

CURWOOD: Well, let's hear from one of those kids. This is a boy named Izerman. He's nine years old at the time you recorded this. He's playing at the beach picking up crabs and little sea creatures, talking about why he likes living on the Marshall Islands.

IZERMAN: The Marshall Islands, you can go outside, you can sleep in. There are no much cities anywhere. It's kind of like you're free. In my opinion, it's the only place that I would ever live in if I had to choose.

CURWOOD: But of course his family may have to choose. How untenable is it to live on the Marshall Islands right now. What are residents looking at, say, by the end of the century in terms of sea level rise?

WORTH: What the projections show is that in the worst case scenario in 100 years nearly every inch of these islands will be underwater, but that's the worst case scenario, and best case scenario is the advance of sea level rise will be much slower, and the people who live on islands like Majuro will have much longer time to adapt and to think about their future. As far as when people may have to leave, habitability is a really complicated question. So what is habitable to one person isn't habitable to another. One community might be willing to live with devastating annual floods and another community would not, but what we do know is the Marshallese have found ways to live on these islands for 2,000 years, and in an environment that most people would describe as extremely isolated and unforgiving. So, they are looking for ways to adapt.

CURWOOD: So, how are they getting fresh water on the island? I mean how much of this in terms of saltwater intrusion already, and for that matter, what about growing food? I mean, salt water is not great for agriculture.

WORTH: Saltwater intrusion is a big problem for agriculture. They're working on collecting rainwater more as drinking water, but that doesn't solve the problem of how they grow things. But there are these projects to have raised beds that buy them a meter, you know, buy them three feet. People that live on these islands are resourceful and they're thinking deeply about how to survive there as long as possible.

CURWOOD: Of course, the US has a long history in the Marshall Islands. In the 50s, our military tested, I think, it's a total of 67 nuclear bombs on the Bikini Atoll. Tell me a bit about that history.

WORTH: So, after World War II, the United States was looking for somewhere to test its most powerful nuclear weapons, and they chose the Marshall Islands because they seem to - from the US perspective to be far away from anything and small and powerless. Of course, for the Marshallese, they are not far away from anything – they are home – and it involved displacing many people.

CURWOOD: One of the children in your movie is a descendant of one of the families that had to leave Bikini during the atom bomb testing. She is 14-year-old Julia and in your film, she's wearing her school uniform. There's a picture of a nuclear explosion on it when you were talking to her. Let's hear a bit from her.

JULIA: I feel alone and sad because Bikini people are not there at their own land, and we are borrowing someone's own land to live. It's like homeless, yeah. If we move from here, I will be embarrassed, sad, angry and mad. I think it might happen because people are not listening.

CURWOOD: What does she mean there, "not listening"?

WORTH: They are watching what the world is doing, and the Marshallese have taken a real leadership role in the UN talks around climate change, and they have pushed for very ambitious goals to be set by the world. They have watched the world set less ambitious goals than the Marshall Islands would like them to, and now they're watching the US under the Trump administration back away from its promises and back out of the Paris agreement. So, even the goals that have been set are not looking as likely to be achieved as they did a couple years ago. And even kids are aware of this in the Marshall Islands and that is probably what she meant when she said people are not listening.

CURWOOD: How ironic is that Julia's family had to leave Bikini because of the nuclear weapons testing and now as the world's second largest emitter of greenhouse gases, we are forcing this current generation eventually to abandon their homes as well?

WORTH: That's not lost on the Marshallese. There's a very interesting historical touchstone for the Marshallese of being displaced. They've already experienced displacement and it's a really sensitive issue for them. It's caused multi-generational trauma for them, and so when they think about being displaced again, again by forces that are out of their control, they can grasp what that will look like for them and the pain it will cause generations of their people.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, it's not that difficult, despite the anti-immigration climate right now in this country, for Marshall Islanders, the Marshallese, to come, to live and work in the United States for the longest time it was a U.S. territory, and I guess is part of the compensation package for all the nuclear bombs being tested there. But, Kate, I believe you didn't talk to anyone who wanted to emigrate. In fact, there was 12-year old Wilmer who says he wants to be president of the Marshall Islands when he grows up, and he makes that point in such a poignant way.

WILMER: I think when the Marshall Islands will be gone, it's like the end of life to me,

like the end of the world. Imagining that is very horrifying, because I'm dedicated to this

place. Like I was destined to be in this place. That's why I'm going to stay and I'm not

going to leave. I'm going to stay and watch even if it means to drown.

CURWOOD: Whoa, that's such a sorrowful thought for such a young person.

WORTH: Yeah, we didn't speak to anyone who wanted to leave. I mean, the Marshallese have been living on these islands for 2,000 years. As former president Christopher Loeak are told United Nations, "Everything I know and everyone I love is in the hands of those of us here today." He said that at Paris, the meeting in Paris, that led to the Paris accord. It's their home, it's their culture, it's the best. For them it's the only place they want to be.

CURWOOD: What's next now for these people living in the Marshall Islands?

WORTH: Well, what the science shows is they're going to be experiencing more nuisance floods many times a year, more serious floods. Every few years and then eventually every year, their water table is going to become salted. They're going to experience more droughts. But they're also looking for ways to survive and thrive despite these challenges.

CURWOOD: The interactive documentary, "The Last Generation" is a joint project with the Ground Truth project and Frontline/PBS. Katie Worth is a reporter for it, and Katie, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

WORTH: You're so welcome, and thanks for having me.

Related links:

- The Last Generation

- GroundTruth Project

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth, former EPA administrator Gina McCarthy has a bold vision in her new job as a professor of Public Health at Harvard University.

MCCARTHY: We wanted to put a different spin and face on climate change and its connection to public health. Why not try to not just fix the planet in the future, but let's fix public health today.

CURWOOD: From rule-maker to change-maker – Gina McCarthy next time on Living on Earth.

Nooks for Nesting

Baby American robins await their parents in the nest. (Photo: © Mike Hamilton)

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: We head from the vast Pacific Ocean – to our North American back yards now. If we’re lucky and plan our plantings carefully. Mary McCann says we can observe a wealth of tuneful companions raising their nestlings. Here’s today BirdNote.

Anna’s Hummingbird returns to its nest. (Photo: © Gregg Thompson)

BirdNote®

Nesting Niches

MCCANN: An American Robin belts out its spring song from the top of a tree. [American Robin song] Perched on the roof of a garden shed, a House Finch joins in with its refrain. [House Finch song] Next, a Song Sparrow hops out of a low thicket and adds its music to the medley.

[Song Sparrow song]

You can find these three species nesting within one small garden, making their nests in a tree, a large shrub, or directly on the ground. By selecting different nesting strata, the species avoid competing for the same nesting sites.

[Medley of the three songs]

An American Robin nests with its young. (Photo: © Tom Grey)

Ground-nesting birds include sparrows, juncos, quails, ducks, and some warblers. These birds are particularly vulnerable to predators and human disturbance while on their nests.

The adult birds will stay on or near the nest while incubating eggs. But once the young depart, the parents leave, too. Birds won’t occupy their nests until the next breeding season.

If you plant your garden in multiple layers—trees both short and tall, shrubs, and ground-hugging thickets—you may be rewarded with a multi-layered medley of bird song.

[More medley of the three songs]

I’m Mary McCann.

###

Written by Frances Wood

Bird audio provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Song of the House Finch and Song Sparrow recorded by G.A. Keller. American Robin song recorded by W.L. Hershberger.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2005-2018 Tune In to Nature.org May 2018 Narrator: Mary McCann

http://birdnote.org/show/nesting-niches

CURWOOD: For some photos – hop on over to our website, loe dot org.

Related link:

This story on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Glen Velez, “Blue Herons” on Pan Eros, CMP Records]

EARTH EAR: SPADEFOOT TOADS AT PLUM ISLAND

[SOUNDS from: https://photos.app.goo.gl/EocUsojmyCP6h54C3]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week, deep in a New England wetland…

[CALLS OF MATING SPADEFOOT TOADS]

CURWOOD: In the company of Eastern Spadefoot toads…

[MORE CALLS OF SPADEFOOT TOADS]

CURWOOD: They get their name from the distinctive bony growth on the bottom of their hind feet which helps them dig backwards deep into the earth, where they lurk most of their time.

[NOISY SPADEFOOT TOADS]

CURWOOD: But in spring and summer, they head to a vernal pool, with their mind on only one thing – mating!

[SPADEFOOT TOADS]

CURWOOD: Naturalist Tom Beaulieu recorded these noisy toads in the rain at the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge on Plum Island, Mass.

[MUSIC: Marian McPartland’s Hickory House Trio, “I Thought About You” by Johnny Mercer/Jimmy Van Heusen, Concord Records.]

CURWOOD: Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Hannah Loss, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Aynsley O’Neill, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

Jake Rego engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org – and like us, please, on our Facebook page – PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth