March 24, 2017

Air Date: March 24, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

U.S. Nixes G20 Climate Finance Declaration

View the page for this story

Leaders of 85% of the world’s economies called for elimination of fossil fuel subsidies in 2009 to help address climate change. But now ina move that could hurt US businesses, the Trump administration and Saudi Arabia have axed climate finance language from the March 2017 G20 session. Harvard economist Joe Aldy discusses with host Steve Curwood the implications and also argues the U.S. should remain in the Paris Climate Agreement. (12:30)

Science Note: Enduring Swifts

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Swedish Scientists have discovered that the common swift can fly for 10 months at a time without landing. Science knows of no other bird that remains aloft for that long. In this week’s note on emerging science, Don Lyman reports that the swifts land for just two months a year to breed in central Europe, but are airborne the other 10 months as they migrate to spend the winter in Africa. (01:50)

El Niño Returns?

View the page for this story

Dramatic winter flooding in California followed by unprecedented rains that buried Peru in feet of mud signal that El Niño may be returning. This just months after a powerful iteration of the weather pattern ended its 2015-2016 rampage through global weather systems, though El Niños are usually spaced years apart. National Center for Atmospheric Research Senior Scientist Kevin Trenberth and host Steve Curwood look at this latest weather surprise on an ever-warming planet. (09:00)

The Place Where You Live: The American River, Sacramento, CA

View the page for this story

Living on Earth gives a voice to Orion magazine’s longtime feature in which readers write about their favorite places. In this week’s edition, Jennifer Berry takes us through a portal into her suburban backyard, which fronts on the American River, and describes the radical changes she saw as the river flooded from California’s record rains this winter. (05:55)

.jpg)

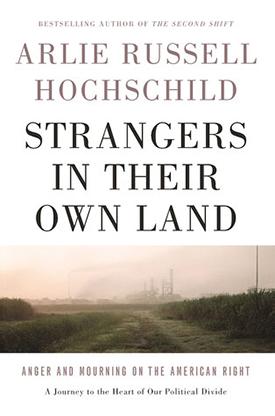

Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right

View the page for this story

A California sociologist ventured out of her liberal bubble to try to grasp why some conservatives reject government regulations in Louisiana, even as industry pollution persists - largely unchecked - for years. Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood interviewed Arlie Russell Hochschild, author of the book Strangers in their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. (16:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Joe Aldy, Kevin Trenberth, Arlie Hochschild, Jennifer Berry

REPORTERS: Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. US and Saudi diplomats have pressured the major economic nations of the G20 to ditch all mention of climate finance from a vital upcoming meeting and that could be bad news for the American economy.

ALDY: It may even have an adverse impact on U.S. firms, on U.S. businesses who might want to promote investment in these developing countries if people look at their government and say, "If your government's not stepping up, why should we go to you for our business?" and instead they'll go to our competitors in Europe or Japan or China.

CURWOOD: Also, El Niño may be behind unprecedented flooding in South America.

TRENBERTH: This time, as far as I can tell, some of the flooding is really devastating. I mean the magnitude of the sea surface temperatures anomalies are as high as they've ever been. We're breaking records around the world in association with the warming of the planet.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

U.S. Nixes G20 Climate Finance Declaration

The G20 is a forum for the heads of state of the world’s major economies to meet to discuss how their countries’ policies impact the global economy. Above, world leaders met in Toronto, Canada for the 2010 summit. (Photo: Number 10, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

With the new Trump administration, it can be hard to discern facts from fiction and promises from performance. So when candidate Trump pledged to pull the U.S. out of the Paris climate agreement it was unclear whether, when, and how he would break America’s promise to the world to take effective climate action. Mr. Trump’s budget proposals to slash climate research and regulatory actions have been important signs, but those have yet to be enacted.

Well, now the U.S. is taking official action to back away from a key element of the Paris deal — money to help the most climate-endangered countries manage those impacts. Acting with Saudi Arabia the U.S. has pulled climate finance off the agenda of an upcoming meeting of the G20. To explain more, we’re joined now by Harvard economist Joe Aldy, who served in the Obama White House.

Joe, welcome back to Living on Earth.

ALDY: Thanks, Steve. It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: Just for the record, who is in the G20 and, in particular, why does it matter for climate discussions?

ALDY: Well, the G20 represents the largest developed and developing countries. It's every country you can think of that plays a major role in economic production and trade. So you have the U.S, and China, many countries from Europe, India, Mexico, Brazil, South Africa, and since the financial crisis and the Great Recession, we've had the heads of state, the leaders of these countries get together at least once a year to discuss the important economic and financial issues and policies around those issues that are really important for the world, and I think what's significant about this is the recognition since 2009 that there's an important role for economic and financial policy when it comes to climate change.

CURWOOD: How has a G20 addressed climate change in the past?

ALDY: Well, I think the most substantial effort taken by the G20 was in 2009. The United States hosted the G20 summit in Pittsburgh that fall, and you had the leaders of the largest developed and developing country say we should eliminate our subsidies on fossil fuels, and I think that has an important impact both in lowering our emissions in the near term, but also creating stronger incentives for firms to invest in renewables or energy efficiency in these markets where they don't have to compete with subsidized fossil fuels. I think that's actually a really big effort and an important effort we've seen in the G20, but I think they've expanded in recent years in addressing more and more the climate change agenda and demonstrating the resolve of heads of state in taking on this issue.

Former President Barack Obama, President Xi Jinping of China and United Nations Secretary General Ban ki-Moon shake hands after the U.S. and China officially joined the Paris Agreement, September 3rd, 2016. (Photo: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

CURWOOD: So, this is a big deal, then, to take climate finance off the table at this moment at the G20.

ALDY: Well, I think it's important, too, because we've seen incredible progress in the international sphere on climate change over the last few years. The fact that we had countries come together so successfully in Paris in 2015 and negotiating the Paris climate agreement; the fact that we, in an incredibly rapid fashion, had countries ratify that agreement so it entered into force last year but perhaps even more importantly than what we’ve seen in terms of agreements, it’s seeing policies and actions in countries around the world, developed and developing, in driving the investment and the deployment of low carbon and climate friendly technologies, and a lot of that is going to be part of using policies to mobilize finance. So the fact that you see a step back in the G20 process, when it comes to climate finance, potentially has a chilling effect when one thinks about how countries will come together later this year in the regular UN climate negotiations.

CURWOOD: Of course, I don't know, the planet might like a chilling effect for global warming. What do you think?

ALDY: [LAUGHS] That would be a nice change of pace.

CURWOOD: I was going to ask, how important is the support of the G20 for climate change action to the success of the Paris Climate Agreement?

ALDY: Well, a big part of the Paris Agreement is recognizing that we're trying to drive emission reductions around the world. We had an unprecedented number of countries say, “Here are pledges for reducing emissions”, but a number those developing countries said, “We can do more in reducing our emissions at home if we have adequate climate finance”. And since t,hat finance will come from those members of the G20, I think it's important that we move forward in identifying our means of finance and the most effective ways of financing those efforts. While I would not expect the Trump administration to put any new monies in the green climate fund, there were monies put in under the Obama ministration, 20 to 25 percent of the initial capitalization of the green climate fund.

I think it is also important to recognize that the world is changing in terms of how we think about the transfers in the support for investment around the world. It used to be a small number of the very wealthiest countries of the OECD, primarily some European countries, the United States and Japan.

We’ve seen in recent years China recognizing that they have the resources, the technical capacity, and the opportunities to help contribute to this effort, and it may be less of an impact in terms of the direct investment out of the green climate fund than the fact it may discourage some developing countries from being more progressive in what they try to do or in their efforts to try to lure more private investment from businesses in climate friendly activities. It may even have an adverse impact on U.S. firms and U.S. businesses who might want to promote investment in these developing countries. If people look at their government say, “If your government's not stepping up, why should we go to you for our business?” and instead they’ll go to our competitors in Europe or Japan or China.

CURWOOD: And we should note that Russia, which is a part of the G20, did not step back from this financing mechanism communiqué.

ALDY: No, and I think what's important is, just a few years ago Russia hosted a G20. When you are the host of a G20 you often have a lot of influence in shaping the leaders’ communiqué, and in that there are a number of important statements about how leaders encourage the effort moving forward on climate change in the UN negotiations and are embracing efforts identifying the best ways forward among G20 countries in financing climate change investment.

CURWOOD: Now, Joe, how confident are you about U.S. participation in the Paris Agreement continuing? Of course, President Trump has called for canceling U.S. participation in the deal but, of course, President Trump has said a number of things.

President Trump has called climate change a hoax “created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive” (Photo: Michael Vadon, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

ALDY: I think it's difficult to predict what this administration will do next. You know, the thing I would note is we are a party to the UN Climate Treaty that the first President Bush negotiated and that the U.S. Senate ratified without one dissenting vote, so this has clearly been a bipartisan agreement for more than 25 years. It is something that, even as the second President Bush walked back from Kyoto, they continue to participate in UN climate negotiations.

I think there’s a lot to be said for the value of engaging in the negotiations and having a say in how the institutions evolve over time, even if the Trump administration decides to walk back on the Obama administration's climate goals. And I think those who engage in the diplomacy recognize that, even if this is not a first-tier issue for the Trump administration, it is for other countries in the world, and some of those countries the Trump administration will want to work on issues that the Trump administration thinks are of primary importance, whether it's on immigration or cyber security or counterterrorism efforts. And so I think building and maintaining those relationships by staying in the Paris Agreement may make it easier for the Trump administration to secure progress on their top priority foreign policy issues.

CURWOOD: Now, China is stepping up to the plate of climate leadership, now that the U.S. is backing off. Joe, you're an economist. What implications does that have for not just global climate politics, but the global and U.S. economy?

ALDY: Well, I think it's important that a predictable policy framework, can create strong incentives for investment and especially investment in the clean energy sector. We've seen incredible investment in China, not just in renewable power and the deployment of it, but in the manufacturing of it. China now is the leading economy when it comes to the manufacturer of solar panels and the components that go into solar panels, and I think their continued progress in climate change policy domestically, the fact that they plan to move forward with an economy-wide cap and trade program here very soon, sends continued signals that there will be a market for those technologies, and as other countries around the world move forward with their domestic climate change programs, they may look to China as the source of a lot of the energy equipment and capital they need to implement their policies. So, as we see a dramatic change in our approach to climate policies here in the U.S, I think that has potentially a dampening effect on investment and manufacturing capacity here in the U.S. for that next generation of climate change technologies.

CURWOOD: So, dust off your crystal bowl. How long can the Trump administration hold out with a negative view of taking action on climate? It seems that there are economic threats with China's leadership. Obviously there are the physical threats of climate disruption. Republicans, I gather, under age 35 pretty much are very concerned about the climate. I mean, how long do you think this administration can last as an opponent of climate action?

ALDY: Well, I think they've demonstrated in the first few months that they will at least state policies consistent with their campaign pledges even if the implementation of those have been rocky, have been challenged successfully in the courts. I suspect that they will say, “We're going to roll back the Clean Power Plan”, but the thing is that that's not done as soon as the president signs an executive order. That is going to be a multi-year process in terms of having to do a new rule-making, and, if they don't go through that process, they go to the courts, and if they don't do the process, they lose quickly in the courts, and I think the EPA understands that. I think Administrator Pruitt understands that.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has spoken in favor of the U.S. remaining in the Paris Agreement, counter to rhetoric from White House chief strategist Steve Bannon and the President himself. (Photo: U.S. Air Force Staff Sgt. Jette Carr / DOD, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

How long will they be able to get away with this? I think it’s a question of when do we think there is going to be real political cost, and maybe not necessarily to Trump directly, but political cost for members of Congress for continuing to deny climate science, for continuing to rail against anything that is consistent with investing in clean energy manufacturing, for continuing to claim that it’s Obama regulations, as opposed to cheap natural gas, that is impacting coal.

CURWOOD: Joe, I think it's...Well, it’s rather ironic that the member of the Trump cabinet who has been clear about supporting Paris is the Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, who at the same time, has been accused of using an alias email account to discuss climate change within Exxon, where he served as CEO for a decade. In fact, Exxon is now being investigated by some Attorneys General over potentially misleading investors about climate change. What does that do for our international standing, to have our leading diplomat be in such a, well, awkward position regarding climate?

ALDY: Well, it may be second order to the awkwardness associated with some of the statements that comes from the president himself. I think it says something that you have the former head of the largest oil company in the world say, “We ought to do something about climate change. We support the framework that came out of the Paris Agreement”, a company that has actually been out there in the past, saying they want or at least support a carbon tax. That, I think, it may say something that even those who you would think have a strong vested interest in challenging climate policy will go out there and say, “We need to be a part of this process, that this is in the long term, we recognize that we're going to have to do something about climate change. That means we're going to have climate change policy.”

And while we may see in the short term efforts by the Trump administration in rolling back some of the Obama era regulations, we're going to be going towards a lower carbon economic development path. We're going to see more meaningful climate change policies. So, I think you'll still see some of the private sector investment recognize the threats of climate change, even if we have this administration denying the reality of the science and what's happening with the global climate.

CURWOOD: Joe Aldy is an economist and a former staffer for the Obama White House, now an Associate Professor at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. Joe, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

ALDY: Thank you, Steve. I’ve enjoyed it.

Related links:

- The G20 draft communiqué from the March 18th meeting in Baden, Germany

- Reuters: “Climate change financing dropped from G20 draft statement”

- UNFCCC Newsroom: investors call for G20 to phase out fossil fuel subsidies by 2020

- NYTimes: “Top Trump Advisors Are Split on Paris Agreement on Climate Change”

- About Joe Aldy

CURWOOD. You can hear our program anytime on our website or get an audio download. The address is LOE dot org. That's LOE.org. There you’ll also find pictures and more information about our stories. And we’d like to hear from you. You can reach us at comments@LOE.org. Once again, comments@LOE.org. Our postal address is Post Office Box 990007, Boston, Massachusetts, 02199.

[MUSIC: The Klezmatics featuring John Medeski, “Moroccan Game” on Possessed, Frank London, Xenophile Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...floods in Peru, and perhaps an early return of El Niño. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Klezmatics, “Beggar’s Dance” on Possessed, Frank London, Xenophile Records]

Science Note: Enduring Swifts

A Common Swift. (Photo: pau.artigas, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Just ahead, another visit to the place where you live, but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: The common swift has an evocative name, but maybe it deserves a different label, such as ‘persistent’ or ‘enduring’, because scientists at Lund University in Sweden have discovered that this medium-sized bird, with its 15 inch wingspan, can fly for 10 months at a time without landing. No other species of bird remains airborne for that long.

The researchers followed 13 swifts, some over a two year period, using a device called a microdata log, that was attached to each bird and recorded whether the birds were in the air, where they had been, and how fast they were flying.

Their findings revealed that these common swifts landed for just two months a year, during the breeding season in central Europe. The remaining 10 months were spent in the air, migrating and spending the winter south of the Sahara Desert.

Some of the birds landed for brief periods during the night, but even these birds spent more than 99 percent of the 10 month period in the air. And data from some swifts showed they did not land at all for 10 months.

The scientists said that this new finding raises new questions, such as how the birds deal with high energy needs while flying non-stop for 10 months, and how they sleep in the air. Researchers speculate that the swifts might sleep while gliding from high altitudes.

As well as setting a bird-flight endurance record, this discovery significantly pushes the boundaries of what we know about animals’ physical capabilities.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related links:

- American Assn. Advance of Science summary of Lund Univ. swift research

- About the Common Swift on Archive

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

El Niño Returns?

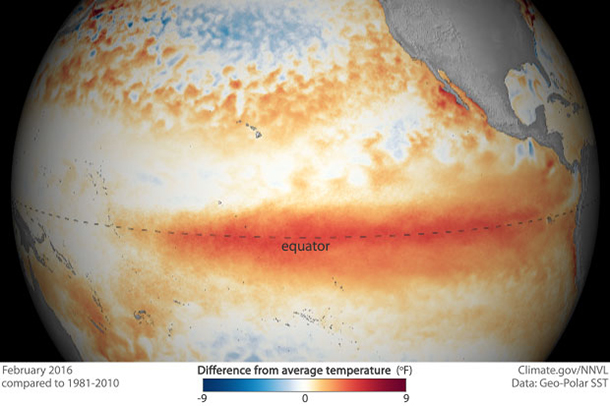

As the 2015-2016 El Niño episode was waning, sea surface temperatures in February 2016 remained warmer than average. A year later, warm sea temperatures suggest the Pacific may be gearing up for a repeat of the weather pattern. (Photo: Climate.gov/NNVL, Data: Geo-Polar SST)

CURWOOD: Unprecedented flooding has swept through Peru in recent days, leaving parts of its capital, Lima, buried under feet of mud. Heavy rain along the west coast of South America is often due to El Niño, the presence of warmer than usual water off the coast there that often has profound effects on weather around the globe. Starting in 2015, a powerful El Niño pattern promoted extreme rains and drought, but climate experts are wondering if we could be facing another one in 2017, even though there’s typically three to seven years between the phenomena.

Well, for some explanation of what might be going on, we turn to climate expert Kevin Trenberth, senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Kevin.

TRENBERTH: Yes, it's good to see you again.

CURWOOD: For those folks who don't regularly listen to the program or who may be new to this topic, where does the term El Niño come from?

TRENBERTH: Well, “El Niño” is a term that grew up off of the coast of South America, and it referred to originally a warm current that came down from the north along the coast, and it came around Christmas time, and that's where the term Niño came from. It referred to El Niño the Christ child, but then every few years or so it turned out this current was much warmer than normal, and the term El Niño then came to take on this name for the anomalous conditions, and so then we refer to this as an “El Niño event.” In more recent times it's been recognized that this coastal event is very much related in general to a basin-wide phenomenon, and that's the one which is important for many other parts of the world as well.

The term “El Niño” originated among communities like Lima, Peru that lie along the Pacific coast of South America. It described a surge of warm water from the north that typically coincided with Christmas, the time of the Christ Child—‘El Niño' in the Spanish language. (Photo: Fernando Stankuns, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Why does the El Niño phenomenon have such an effect on planet conditions everywhere around the planet?

TRENBERTH: It relates to the sea surface temperatures and the fact that it occurs in the tropics, and right now there’s sort of the coastal El Niño van off the coast of Peru. The temperatures there are more than three degrees Celsius, over five degrees Fahrenheit, above normal, and as a result that becomes a center of action. That's where all of the air tends to move towards the heavy rainfalls that occur there. In turn, those heavy rainfalls change the heating patterns in the atmosphere, and that acts a little bit like a rock in a stream, and it sets up ripples downstream, and so it affects the jet stream of North America and other places around the world, and so it changes the weather patterns.

CURWOOD: Now, recently we've seen these horrific floods in Peru that are related to, as you say, a coastal El Niño. How unusual are these floods and coming right on the heels of the California flooding?

TRENBERTH: Yes, it is not uncommon, actually, to have some sort of a mirror image across the equator. So, we have flooding in California and we have flooding in coastal South America. You know, last year, we had flooding in the Missouri at the same time there was major flooding in Bolivia. And this time, as far as I can tell, some of the flooding has been really devastating. I mean, the magnitude of the sea surface temperatures anomalies are as high as they've ever been.

CURWOOD: What does this phenomena, what do these floods tell us about the likelihood of a global El Niño emerging again? It seems like we just one.

Engineers construct flood barriers along the Los Angeles river in anticipation of 2016 El Niño conditions. (Photo: US Army Corps of Engineers, Los Angeles District, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

TRENBERTH: Yes, it's very interesting from that standpoint because we've had this major El Niño event from 2015 through 2016, and it died away about a year ago, and to have another one developing along the coast of South America so soon is quite unusual, and so it's a big question as to whether this will now expand into the central Pacific especially since it's coming so closely on the heels of the previous event.

CURWOOD: It seems that for years there was some regularity to these cycles, El Niño, and then La Niña is the opposite, right? How much of that has changed, do you think?

TRENBERTH: Yes, so, conditions are very seldom average in the tropics. It's really always going from El Niño to La Niña, which is the cool phase in the tropical Pacific, and then back again, and the average period is around four years, but we generally say that it say three to seven years because it's not a complete rhythm. So, having another one almost a year after the previous one is fairly unusual but not unprecedented.

CURWOOD: So, what is the relationship, if any, between climate change, climate disruption and the El Niño phenomenon?

TRENBERTH: This is a really good question. We're not sure exactly how the El Niño phenomenon and will change or whether it will change much in association with climate change aspects. What is clear, though, is that when it rains, it rains harder. There is a greater risk of floods, and at the same time other parts of the world are suffering from droughts, and so both the droughts and the floods become more extreme in association with the global warming aspects.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) installs buoys like this one in bodies of water around the world to collect climate data. The organization’s shrinking budget has prevented necessary repairs to buoys monitoring El Niño conditions in the Pacific Ocean. (Photo: NOAA, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, we've had an unusual year. California is just emerging from a lot of flooding. Chile and Peru are suffering from flooding right now, and with the question of a coastal El Niño...If a full El Niño starts to develop, what might that say to us about global warming, climate disruption?

TRENBERTH: Well, this is a good question as to exactly what will happen. It would be surprising if there was a substantial El Niño that grows out of this because we’ve just had one, and that has actually taken some heat out of the tropical Pacific Ocean, and in that sense, there is less fuel available for the next one. But nevertheless, these El Niño events can be manifested in somewhat different ways so that there's no really good analogs that we can go by, and one of the tasks we have as a research community is to try to build better climate models that we can simulate these and make better predictions into the future.

CURWOOD: So, we called you up because this is one of the years that it's, well, kind of “strap yourself in”, in terms of weather phenomena in all kinds of ways. We've seen a rapidly warming Arctic, these devastating droughts and, of course, the level of CO2 keeps going up. How much climate disruption are we starting to see that we could attribute to our human activity?

TRENBERTH: Well, there's a lot that's been going on and, of course, a lot went on in the last couple of years in association with the El Niño event. Last year, there was major flooding in and around the Houston area around April, and then there were these very unusual, so called “thousand-year flooding events” in Louisiana around August, and then the unprecedented flooding that occurred in association with Hurricane Matthew especially in the Carolinas in October. Other parts of the world have experienced devastating droughts in South Africa and in other parts of Africa, in Indonesia and Borneo, and many wildfires associated with the drought conditions. And so there's no doubt whatsoever that global warming is continuing, and that's largely caused by human activities and it's already having consequences, and those consequences could easily be in the neighborhood of the tens of billions of dollars a year.

Kevin Trenberth is a distinguished senior scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research. (Photo: National Center for Atmospheric Research)

CURWOOD: Now, the National Center for Atmospheric Research there in Boulder has gotten close to two thirds of its budget from the National Science Foundation, and most of the rest comes from other federal agencies, the Federal Aviation Administration, NASA, and NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. How is morale there in the present political climate where there's a lot of talk about cutting, maybe even eliminating funding for you guys?

TRENBERTH: Yes, well climate is certainly under attack. That's true in the so-called skinny budget that's been released by the administration, but we're very dependent upon DOE and NOAA and NASA and other funds, and so there is great concern.

CURWOOD: And what kind of things might we lose in science if this funding is cut?

TRENBERTH: Well, there is a good example here, in fact. NOAA funding has been cut in the realm of climate since about 2012, and this had consequences because the El Niño monitoring system in the tropical Pacific decayed. There’s a number buoys that are deployed throughout the Pacific - something like 79 or something like that - and they have to be serviced about once a year by oceanographic ships, and they decayed in 2014, and then this big El Niño came along, and we weren't able to track exactly what was going on as well as we would like. Many things which are not directly related to climate change even, as long as they are related to climate, are under threat now.

CURWOOD: Kevin Trenberth is a distinguished Senior Scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

TRENBERTH: Oh, you're most welcome.

Related links:

- Reuters: “Abnormal El Niño in Peru unleashes deadly downpours; more flooding seen”

- National Center for Atmospheric Research

The Place Where You Live: The American River, Sacramento, CA

The American River at peak flood stage (Photo: Jennifer Berry)

CURWOOD: We stay with the subject of unusual weather and the flooding that’s inundated parts of the west for another installment in the occasional Living on Earth/Orion Magazine series “The Place Where You Live.” Orion invites readers to submit essays to the magazine’s website to put their homes on the map, and we give them a voice.

[MUSIC: Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes “Home” from Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes (Rough Trade Records 2009)]

This essay takes us to a hidden world in California.

BERRY: I live with my husband and our daughters in Sacramento, California, along the American River. We look like we're situated in the middle of the city, but when you walk into the backyard it’s as though you've traveled through a portal, and you ended up on an episode of "Wild Kingdom". It's this river and wildlife that defines this place that we call home. I'm Jennifer Berry, and this is my essay on the American River.

The first sighting of the resident osprey after the flood (Photo: Jennifer Berry)

Bundled in warm clothes, we breakfast along the American River, enjoying a temporary parting of clouds after weeks of rain. We eat in silent reverence for the landscape we call home, absorbing the transformed land.

[SOUND OF RUSHING RIVER]

The river rose an estimated 15 feet, burying trees to their canopies, swallowing the island between its two forks, and marooning logs and entangling debris atop bushes. This spooky sea climbed up the bank towards our home.

Our resident Osprey flies by the first time this year.

[OSPREY CALLS]

I exhale, relieved. I noted its absence and wondered if this unrecognizable river drove it away. I noted the unusually close proximity of the Red-tailed Hawk resting on our breakfast table,

[RED-TAILED HAWK CALL]

During the flood, a red-tailed hawk perched on Jennifer Berry’s breakfast table (Photo: Jennifer Berry)

then the Cooper’s Hawk waiting on the nearby perch we mounted for song birds.

[CALL OF COOPER’S HAWK]

We talk about the ground-dwelling creatures of the island and riparian corridor that were washed away. What happened to the coyote pack that ruled the riverbanks and met our gaze on frequent encounters? The beaver dam upstream has been swept away too. No wading birds, except a lone Great Egret braves the turbulence, standing upon a snarl of tree branches and roots in the middle of this sea, staring into the white-capped, muddy current.

I want to interpret this as destruction, but nature has other ideas. The Great Blue Herons fly in on schedule and claim their nests in the rookery. Abundant Tree Swallows fly at sharp angles and dips. Winter’s diving ducks have repositioned themselves away from the swift current to feed, bobbing on the choppy surface between dives. And the cottontails and quail moved out of the floodplain and into our hedges. Canada Geese settle onto the first land exposed as the river recedes. My husband spots a California sea lion upstream, chasing this year’s healthy run of fish more than 80 miles up the Delta.

[BARKING OF SEA LION]

The deluge reshaped the banks and riverbed and matted the trees along the river with debris (Photo: Jennifer Berry)

It’s dusk. I’m out at the river again. I admire the silhouettes of the naked trees and the sky’s light that illuminates the river. I note the biorhythms of the natural world, and I am awed and comforted by its ability to adapt and carry on.

[MUSIC: Jimmy LaValle, "Streamside," The Album Leaf, In a Safe Place, compilation, Sub Pop]

Back at our home, the landscape looks like it's been through a natural disaster. The riverbed has been reborn into strange land masses, and the rolling hills on the island between the forks are now eroded cliffs, and giant trees have been knocked down, carried downstream, carried and deposited in the weirdest of places. And the trees and bushes still standing are matted with debris and human litter.

I want to be sad when I see it, but the life all around me doesn't let me. Nature has this way of surviving in the middle of the aftermath of this flood, and I come to realize that nature doesn't think about what was, like we do. It just works with what is. Even after years, we see something amazing every day, whether it's a family of beavers swimming across the river at sunset, an osprey with a giant fish flopping in its talons so close I can look in its eye, or a group of bucks with enormous antlers swimming across in this tight-knit pack and then galloping through the hills onto the other side. We have coyote packs [COYOTE HOWLS]that run along the river and howl late at night, and we'll fling ourselves from our beds and run out onto the patio to see if we can see them.

Jennifer Berry and her dog along the river at sunset, before the flood (Photo: Jennifer Berry)

My husband and I have a tradition. Every night, when the sun is about to go down, one of us calls, "Sunset!", and we stop what we are doing. We grab our binoculars and our dogs,

[SOUNDS OF PANTING DOGS]

and we head out to our Adirondak chairs and watch as the natural world goes about its nightly routines, reconnect with each other, decompress, recompose ourselves. And there's something amazing recommuning with nature in that way. It's alive our here, and that does something to your soul when you're a part of it, and I don't know if we can separate this location with who we are anymore.

[MUSIC: Jimmy LaValle, "Streamside," The Album Leaf, In a Safe Place, compilation, Sub Pop]

CURWOOD: That’s Jennifer Berry and her essay on the floods in her backyard on the American river. You can find details about Orion Magazine and how to submit your essay, if you want to tell us about the place where you live at our website, LOE.org.

Coming up, why people hurt by pollution sometimes vote against environmental protectors. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

Related links:

- Jennifer Berry's essay on the Orion website

- Berry Ink, Jennifer Berry’s website showcasing her freelance writing

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Tom Teasley, “Nights Over Baghdad” on All the World’s a Stage, self-published]

Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right

.jpg)

An aerial view of the sinkhole at Bayou Corne (National Nuclear Security Administration, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The present partisan divide in America has led to a number of ironies, including voters in so-called red states who seem to vote against their own best interests when it comes to regulating air quality and stream pollution. To try to understand and bridge that gap, liberal sociologist Arlie Hochschild spent five years conducting what she calls “an empathic study” of her political opposites in Louisiana for her book, “Strangers In Their Own Land.”

Arlie is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley and she joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

HOCHSCHILD: Well, thank you. I'm delighted to be here.

CURWOOD: So, briefly describe for me the project that this book is the result of.

HOCHSCHILD: Already five years ago I was concerned about a growing split between left and right across the country, and I realized that I lived in an enclave, a geographic enclave, a media enclave, an electronic enclave, and that we all do. So, I decided to get out of my enclave in Berkeley, California, and go as far right as Berkeley, California, is left. Take my moral and political alarm system off and try to really cross over an empathy wall.

CURWOOD: And you chose Louisiana for this project. What makes Louisiana such an ideal choice for the types of perspectives you were hoping to document?

HOCHSCHILD: I wanted to go where the right was the strongest and had grown the fastest and that was the south. Actually, when you look at the proportion of whites who voted for Barack Obama in 2012, in California it was half. In the south as a whole region, it was a third. But in Louisiana it was 14 percent, so I thought, “It's the Super South, that's perfect, that's just where I want to go”.

CURWOOD: It would seem, these people who lost their neighborhood, much of a way of life should be interested in the federal government trying to clean things up, but it's exactly the opposite. Why?

Arlie Hochschild’s newest book is a sociological investigation of the American right. (Photo: The New Press)

HOCHSCHILD: Well, let me just say to begin with that the people I came to meet love the birds, and they love the water and they love the grand Cypress trees, these queens of the wetlands. They love nature, and it wasn't that they didn't know about the pollution. Yes, of course, they did. Louisiana has the second highest death rate from cancer for men.

So, I think there were three things. They felt that the federal government, that was the north, and it was always wagging its moral finger at the south, and they felt that environmentalists were, you know, the last in a series of northerners coming down to tell them the right thing to do.

I think the next most important reason they distrusted the federal government is their experience with protective agencies in the state of Louisiana, and they thought, “Gosh, these are a lot of people we pay taxes to but they don't really protect us”. And they are right, because Louisiana is an oil state - that was a big discovery for me - and it outsources, in a way, the moral dirty work to the state. So, the state actually pretends to protect the citizenry from hazardous waste and pollution of air and water and ground, but it doesn't actually protect it very much. It gives out permits, as one Tea Party person said "like candy". So, they felt the federal government is just a bigger, badder version of the state government which isn't protecting us. So, they'd had bad experience. They’d been burned, and I think that's the second kind of source of resistance to the government. But the third is that they saw the government as an instrument of what I'll call 'the line cutters.'

Arlie Hochschild and Bayou Corne resident Mike Schaff. (Photo: Arlie Hochschild)

CURWOOD: This “line cutters” concept is really a fascinating one in your book. Stop for a moment and tell me exactly what do you mean by “line cutters,” and why people in the south...although I imagine anybody listening to us probably doesn't really like the notion of somebody coming in front of them if they're waiting for something.

HOCHSCHILD: The right deep story is this. You're waiting in line for the American dream. It’s as in a pilgrimage, looking at the top of the hill at which stands this much desired American dream, and you're not in the back of the line, but it hasn't moved for many, many years. Some people I interviewed hadn't gotten a raise in two decades. So, your feet are getting tired. You feel like you don't bear grudges to any particular group. You're a good person. You've worked hard. You've played by the rules, and you deserve the prize at the top of the hill.

Then, you see some people that seem to you to be cutting in line. Well, who are they? They are blacks, who now through federally mandated, affirmative action program, have access to jobs that used to be reserved for whites. Even worse, women who through federally mandated affirmative action now have access to jobs that used to be available only to men. And then you have immigrants, and then you have refugees. So, all these intruders.

And then, another moment of the right's deep story. Barack Obama, supervisor of this line seems to be waving to the line cutters. In fact, you know, isn't he sponsoring these line cutters, and isn't he a line cutter? Many people said to me, “How did a single mother, his mother, pay for a very expensive education at Harvard and Columbia. Something fishy”. So, they felt that he too wasn't obeying by the rules.

CURWOOD: Arlie, you don't talk much about race in your book. In the south, no matter how bad things were, you could look back and say well the blacks have it worse, the Negroes have it worse. So, it seems that part of this distrust of government may come from this change, this loss of comfort that, well, no matter how tough it is for poor white folks, that there are poor black folks behind them, and that comfort goes away or is going away.

In 2014, Bayou Corne was -- for the most part – devoid of its residents. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

HOCHSCHILD: Right. They don't think of themselves as racist, are insulted to turn on the television and see that they are seen this way. One man told me, “Oh, it's only the liberals that think we are more racist than they are”. And many people said, “Look, racism isn't gone by a long shot in this country, but we're not the only ones”. And race was, of course, an enormous part of the story and I do talk about it in the book, but it was woven together with the sense of decline and fear and sense of being invisible to the authorities.

CURWOOD: Now, among other instances of industrial pollution that your book discusses, Arlie, you deal with the sinkhole that appeared in Louisiana in 2012. It formed in a Cypress grove just outside of a town called Bayou Corne. The cavern was created by a collapsed underground salt dome cavern operated by Texas Pride, a company that was there extracting sodium chloride, salt, for plastic production. Hundreds had to be evacuated from their homes, and it was only in 2016 that the mandatory evacuation order was lifted. Now, Emmett FitzGerald reported for Living on Earth from Bayou Corne in 2013. Let's listen to an excerpt from one of his pieces where he met with residents who were worried about the danger of explosive gas collection in the cavern.

FITZGERALD: Jennifer Gregoire, living on Sauce Picante decided to live with that risk. She says she doesn't have much of a choice.

GREGOIRE: I understand the dangers and the risk I'm putting my family in, but it's cheaper and it's easier. I can't afford to buy nothing else.

FITZGERALD: The Gregoires are only about 20 families left in Bayou Corn. If a car drives down Sauce Picante today, it's likely either tourists or looters. Jennifer says it's no longer a good place to raise a family.

GREGOIRE: My son just had a birthday. We can’t [SOUND OF GREGOIRE CRYING], we couldn't throw a party for him this year at the house. That was bad. Nobody wants to come here.

CURWOOD: That's Bayou Corne mother Jennifer Gregoire in Emmett Fitzgerald's story. Now, in your research into Bayou Corne and the Bayou Corne sinkhold, you spoke with Bayou Corne resident Mike Schaff. Now, Schaff loses a lot, but why does he continue to oppose federal environmental regulations and in spite of his own self-professed desire to protect the environment?

High levels of hydrogen sulfide were detected at a Texas Brine Company well near the sinkhole back in 2012. (Photo: Arlie Hochschild)

HOCHSCHILD: Yes, You know it's poignant because the first thing Mike told me is, "You know the problem with federal government is, it takes community away. It supplants community. We ought to do for each other the things that government does for us. We're better off if we have local type community."

But it wasn't the presence of government that took a community away from Mike Schaff. It was the absence of government regulation that took community away from Mike Schaff, and when we talked about that later on a fishing trip and, more recently, I brought my son who is a California environmentalist, a member of the Energy Commission in charge of renewables – so, a progressive Democrat just the opposite of Mike - and we went out fishing, the three of us. And I said, "Look I'm going to hold the tape recorder, but I'd like us to get together and tell me, is there common ground on how to prevent another Bayou Corne sinkhold from ever happening in America"?

And they went to it, and they did come up with some common ground. And Mike, very hesitant to call for regulation, he had been so exposed to a bad model of government, and he'd spoken out at one after another after another meeting to deaf ears, and he feared that the federal EPA was as bad as the Louisiana one. And yet when David said, 'Yeah, but what else are we going to do here? And there is a possibility of good government. Look, over in California we have a much more tight regulation and less pollution, and you could have it too.' And when he put it that way, Mike said, 'Well, it's not fair that some states are the polluted states and have the worst health. We should live in the United States where every state has the same degree of health and cleanness of the environment.'

Strong support in Southern conservative strongholds was key for Trump’s presidential victory. (Photo: Tammy Anthony Baker, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, the common theme of your book is, these folks who really have been given the short end of the environmental stick, and you kind of divide them – You’re a sociologist - so you have sort of three categories of folks that you talk to. I think the one category you call “the team players.” Another you call “the believers” or “the worshipers,” and then you have a category that you call “the cowboys.” Who are these people and what influences their Tea Party politics in the face of environmental, well, really, environmental dysfunction and environmental degradation?

HOCHSCHILD: The team player is a person who says, “I am fundamentally conservative Republican, and whatever conservative Republican leadership is telling us is the right thing to do. I'm on board for that, and I'm going to be loyal to this team, my team”.

The second would be the worshiper, and here are people who say, “You know, you can't always get what you want”. And I met people who loved the environment, who knew about it in great detail. It hurt them to see a child go swimming in a lake that they knew was polluted, so it's not that they had inured themselves to a love of nature. No, but they felt like they had to renounce that love and in a way say, “Look, pollution is the sacrifice we make for capitalism.

And the third would be the cowboy. The cowboy very differently from that says, “You can't afford to love nature”. What he does is say, “Look, I'm tough. You're tough. Mother Nature's tough. We're all tough, and she can take it. Mother Nature will recover. I won't be hurt. You won't be hurt”. Each of them takes pride at a different moment, takes honor from a different emotional moment in their heart.

CURWOOD: Arlie, drill down a bit for me on one of these. Particularly, what role does Christianity play in how the far right thinks about environmental regulation? Those people who look to fundamental Christianity.

The Cypress tree is the iconic state tree of Louisiana. (Photo: Arlie Hochschild)

HOCHSCHILD: Yes, many of the traditional leaders of the Evangelical church have put a great distance between their faith and protection of the environment so that environmentalists are seen as almost animists, you know, that worship the Earth instead of God, but there's a growing group of Evangelicals who have embraced the idea of creature care and that this is God's creation, and we must protect it for posterity. And they do it with, again, a different set of meanings. There are people, a group of Christians for saving mountain tops, but it's for the sake of the unborn child, so it's got a different take.

CURWOOD: You know, recent statistics show that the life expectancy of white working-class people is declining in this country. How might this be tied to the appeal of the Tea Party to folks who are nonetheless suffering some substantial environmental outrages?

HOCHSCHILD: Yes, you're right, declining, and there's a higher rate of suicide and drug abuse and alcohol abuse. It's a despair. It's a sign of despair, actually. It's almost like what happened to black men, what hit black men earlier. It's hitting blue-collar, white men now, or the fear of it, that the decline of jobs - automation being a major cause of that - is terrifying.

CURWOOD: You spent many hours in conversation with Donald Trump supporters. You did the end of your research just as the election was approaching last year. How does Donald Trump's rhetoric on environmental issues appeal to these folks on the Tea Party right? Or is there something else about what he says that appeals over the environment and other matters?

Arlie Russell Hochschild is a Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. (Photo: University of California Berkeley)

HOCHSCHILD: You have it right the second way. They don't love him for selecting Pruitt who's now going to cut the EPA by a quarter of its staff and undermine the Clean Air and Clean Water Act. No, but they do like the whole idea of a candidate who seems to recognize them. They almost felt like a minority group. Even though they're a majority, they felt that way. I think of Donald Trump as an antidepressant. You know, you see anger, but in the title of my book there's also mourning. You know, anger and mourning on the American right.

CURWOOD: Arlie Russell Hochschild is a sociology professor at the University of California, Berkeley. Her book is called "Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right". Thanks for taking the time with me today.

HOCHSCHILD: It's been a great pleasure.

Related links:

- Strangers in Their Own Land

- Emmett Fitzgerald’s entire Bayou Corne segment

- Arlie Hochschild’s UC Berkeley Faculty Page

[MUSIC: English Baroque Soloists/John Eliot Gardner, “Water Music, Suite in F, Adagio e staccato” on Handel: Water Music, Suites 1, 2 &3, Philips Records]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, chemicals that disrupt the hormone system can reduce fertility and more.

SWAN: Those men who have poor reproduction function say, “Low sperm count.” Several studies have now shown that the overall mortality is higher. In other words, they will die earlier.

CURWOOD: The dangers endocrine disrupters pose for men’s health. That’s next time on Living on Earth.

EARTH EAR – LANG ELLIOTT – LACASSINE POND, LOUISIANA

[SOUNDS OF DAWN CHORUS]

We leave you this week, deep in a Louisiana bayou.

[SOUNDS OF DAWN CHORUS]

It’s dawn in early spring, at Lacassine Pool, a National Wildlife Refuge.

[CHATTERING BIRDS, CHUCKLING LEAST BITTERNS]

Red-winged blackbirds are calling from the thickets around the pool, along with melodious Northern Cardinals and gravel-voiced Boat-Tailed Grackles….

[SOUNDS OF DAWN CHORUS, INCLUDING FROGS]

Along the water’s edge, a Common Moorhen darts in and out of the rushes, and a Least Bittern calls, above a chorus of Northern Cricket Frogs.

[SOUNDS OF DAWN CHORUS]

Lang Elliott recorded this dawn chorus in February, for his sound project, The Music of Nature.

[MUSIC: Dr. John, “I’m an Old Cow Hand” on Mercernary, Johnny Mercer, Parlophone Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Alex Metzger, Kit Norton, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe/Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth