February 6, 2004

Air Date: February 6, 2004

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Alternative Goes Mainstream

View the page for this story

Part 1: For the past five years, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, or NCAM, part of the National Institutes of Health, has been funding research on alternative medicine at major medical schools across the country. Now, for the first time, the Center has decided to fund research based at alternative medical schools. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Dr. Steven Straus, director of NCAM, as well as with Peter Wayne, head of research at the New England School of Acupuncture, about the new program.

Part 2: Host Steve Curwood continues the conversation with Peter Wayne, lead scientist on the new federally funded research program on acupuncture. Joining them is Dr. Julie Buring, a Harvard epidemiologist who’s collaborating on the new study. (29:45)

()

Portrait of a Shrinking Town

/ Jennifer ChuView the page for this story

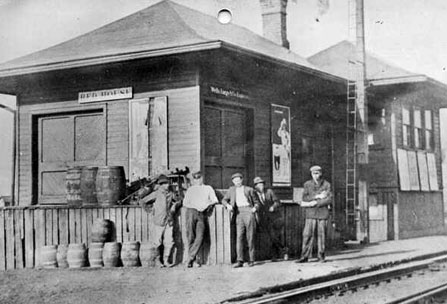

In the mid-1800’s, the business of timber turned a little red house into a bustling river town. More than 1,000 residents lived and worked on the land until the lumber ran out. Now Red House, New York is the smallest town in the state and, according to a deal made more than 30 years ago with the state park there, what remains of the town will eventually go back to the forest. Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu visited with the some of the long-time residents who are keeping Red House history alive. (11:15)

Sounds of Winter

/ Sy MontgomeryView the page for this story

Listen closely. The frigid months of winter have a sound uniquely their own. As commentator Sy Montgomery points out, the cold and gray season’s bareness and rigidity help make its sounds vibrant. (03:30)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Peter Wayne, Julie BuringREPORTERS: Jennifer ChuCOMMENTARY: Sy MontgomeryNOTE: Cynthia Graber

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR - this is Living on Earth.

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. With the popularity of alternative medical therapies such as herbs, movement and acupuncture on the rise, medical schools have been trying to figure out just how they work. Now, the federal government is going one step further by asking alternative practitioners to lead scientific studies that may help open the eyes of physicians and surgeons.

BURING: When I do aspirin, I’ve got a pill. I know exactly what’s in it. I know the dose. I give it to you and you take it. When I’m talking about tai chi, I’m trying to understand-- is it the exercise that’s making a difference? Is it the meditative component? I want to know what’s important. This is the difference between the kinds of things I have traditionally done in terms of intervention and what we are doing now.

CURWOOD: New science and ancient medicine, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Alternative Goes Mainstream

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, welcome to Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The National Institutes of Health oversee the federal government’s medical research projects. The mission is to fund studies on a wide range of topics from cancer to heart disease. With that goal in mind, NIH created a new division six years ago. It’s called the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, or N-CAM. The alternative medicine center has funded hundreds of research projects at major medical schools including Columbia, Johns Hopkins, and Harvard.

But recently the NIH kicked off a new program that’s a radical departure from its existing collaborations. It’s awarded sizable grants to two small schools that teach alternative medicine. The mandate is lead research collaborations that could help bridge the gap between alternative and mainstream medical practices.

Doctor Stephen Straus is director of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Here’s his explanation of why the NIH decided to partner research with alternative medical schools, like those that teach acupuncture, for example.

STRAUS: In this case, we're looking to an environment that has richer experience in acupuncture, that brings its own sense of what the most important opportunities and challenges are, and helps decide what the clinical question should be and how to do the acupuncture. And then enlists partners who are experts in the research, which they're not.

CURWOOD: Dr. Straus says another reason for the unprecedented collaboration is to challenge alternative practitioners to consider the scientific study of their disciplines.

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

CURWOOD: One of the developmental centers is at the Palmer College for Chiropractors in Davenport, Iowa. The other is the New England School of Acupuncture in Watertown, Massachusetts. Peter Wayne is the lead researcher for the acupuncture project, and he joins me now. Peter, I’m curious about how you got your start in this field because, as I understand it, your education and background have nothing to do with acupuncture. Do I have that right? WAYNE: That’s right. My degree is in evolutionary biology. CURWOOD: So, how do you get from evolutionary biology to oriental medicine? WAYNE: Since high school I’ve had two strong interests: one in the natural sciences, especially ecology and evolutionary biology, and one in tai chi, particularly its application to health and some of the philosophy that goes along with tai chi. CURWOOD: So, how’d you’d you get mixed up in acupuncture? WAYNE: Part of the tai chi training is traditional training in Chinese medicine. And while I was in graduate school, and early in my practices, I actually had some training in Japanese medicine and shiatsu. A lot of the practices related to tai chi, chi gung, incorporate training in reading pulses and knowing the meridians of the body and understanding the basic philosophy of yin and yang. So, a big part of my training already included that. CURWOOD: So, the day comes when, I gather, the director of the New England School of Acupuncture asks you to lead the research department. Why did this person pick you? WAYNE: Well, part of it was practical. I’d been teaching tai chi to the students at the acupuncture school for a number of years. And because of my experience in western medicine, in particular, western science, I was asked to help develop the curriculum there. CURWOOD: Why engage in research about acupuncture? It’s been around for thousands of years. Probably more than a billion people use it. So why engage in research about it? WAYNE: It’s a great question and the different parts of me would answer that in different ways. The part of me that has practiced these arts and watched my students and my colleagues benefit greatly from tai chi, from acupuncture, from herbal medicine, believes that this is a wonderful opportunity, a wonderful set of healing modalities to share with the west, and that we can benefit greatly. And we’ve seen it very effective in clinical practice. The scientific part of me has a more objective perspective. It’s curious why it works. It’s curious if it works for all people and under all conditions. We want to know where it works best and, in some cases, where it doesn’t work. CURWOOD: Tell me about some of the research that you’re conducting at the New England School of Acupuncture. WAYNE: We’re doing a number of projects, some of them that began well before the establishment of our developmental center. Some of our earlier work has been looking at acupuncture as a tool for helping with some of the paralysis and quality of life issues for people who’ve suffered a stroke. Some other studies we’re working on include the application of acupuncture for moderate hypertension. And we’ve done a number of trials exploring the use of tai chi on conditions such as chronic heart failures and balance disorders related to inner ear neural damage. CURWOOD: What kind of results have you found from looking at acupuncture and moderate hypertension? WAYNE: Those results aren’t completed yet. This was a pilot study. One of the things that did come out of that study was the bringing together of senior clinicians, in Chinese medicine in particular, and researchers in cardiovascular disease, and to ask how you best design a trial to evaluate acupuncture that both honors the way these practices are done in clinical settings, and at the same time uses rigorous science. And so one of the outcomes of this study, in and of itself, was a very unique design to this trial. CURWOOD: I need to ask you a little bit more about this, because it seems to me that if you try to understand what people in acupuncture do, and you try to put that in western terms, you’ve got a lot of translation difficulties. For example – tell me if I’m wrong about this – hypertension is something that western doctors seem to see as one disease, but in eastern medicine it’s not seen as one disease, right? WAYNE: Yeah, I think translation problem is a really good way to put it. In Chinese medicine there is no disease called hypertension. For example, in our study we were able to pretty much categorize patients into one of five categories using the diagnostic tools of Chinese medicine. And some of these categories sound quite funny. So some patients would be diagnosed as having liver fire. And these patients may look like they have red face, red eyes, headaches. So the energy is rising up into the upper body. Some of the patients may have liver fire with kidney indeficiency. Others may have something called phlegm and dampness – generally an inhibition to the circulation system. So what’s important about that is that each of these groups of patients, depending on their diagnosis, would be treated quite differently. CURWOOD: And when you put this into western research protocol, do you find that, in fact, acupuncture has, say, more of an effect on somebody with liver fire versus somebody who has -- what did you say – phlegm and dampness? WAYNE: Yeah. The results from this particular study are not available to fully evaluate that, but that is one of our primary goals in that study. CURWOOD: Let me ask you about your current studies that you’re doing now in collaboration with Harvard Medical School. What are you looking at and why? WAYNE: As part of the developmental center there are three specific projects that we’re developing. The first one looks at a condition of lowered white blood cell counts resulting from chemotherapy for women who are diagnosed with ovarian cancer. And one of our colleagues at the New England School of Acupuncture, Dr. Weidong Lu, who was trained in China, suggested that the research there would support the idea that acupuncture can boost white blood cell counts. A second study is looking at young women, adolescent girls, who suffer from chronic pelvic pain, primarily related to endometriosis. CURWOOD: So, let me understand what the objective is here. On the one hand, you’re going to treat pain – are you also thinking that the acupuncture might help treat the endometriosis itself? WAYNE: We believe…there is some preliminary evidence that one of the ways that acupuncture influences pain is by changing inflammation and that, in particular, that it can influence a set of chemicals called cytokines. And we’re going to be looking at the levels of these compounds both before and after. CURWOOD: So, what happened when you approached Harvard Medical School with the idea that you do this work together? WAYNE: Actually, we approached each other. We both were aware of this opportunity that the NIH was developing to create these developmental centers. NESA and various aspects of the Harvard Medical School, especially the Osher Institute, have a long history of collaboration. We’ve conducted a number of trials together, we teach at each other’s institutions. And so it was a real natural place to begin this collaborative endeavor. CURWOOD: What were some of the concerns that each side had, do you think? WAYNE: As we discussed before, in many cases when you take a western disease like hypertension, you’re going to have patients with many different diagnoses with respect to Chinese medicine. Each one of them would be treated in a different way, according to Chinese medical theory. And therefore, to have one protocol that meets all the patients needs doesn’t really honor what happens in clinical practice. They need to be tailored to the individual and they may even need to change over time as the individual’s constitution shifts. CURWOOD: So, then how do you adapt the study for this? I can imagine that instead of having a study that looks at hypertension, you have a study that looks at the five different Chinese definitions of hypertension. WAYNE: That’s one of the ways. One of our researchers has developed a very creative approach to this. We call it manualization. The basic gist of it is that there is a set protocol based on principals. In other words, the Chinese medical practitioner said ‘if they have liver fire, then the basic principle is to sedate that fire.’ And to do that we would use these points in these ways. And so the rules are set out in a very clear way, a priori, and scientists, both within our study or in another laboratory that want to repeat our study, can follow these rules in a very clear way. Yet the practitioners have some room to individualize the treatment to the patient. So it’s a marriage between trying to have a repeatable study that someone can do in another place, and at the same time allowing some flexibility. This is a good example of some of the methodological issues we’re tackling. CURWOOD: What do you suppose your background in ecology gives you for this work? WAYNE: I think there’s two things. One, in terms of Chinese medicine, at its heart it’s actually an ecological medicine. We’ve talked about diagnosing people with liver fire and dampness. And, in essence, Chinese medicine looks at the body as an ecosystem with elements to balance and processes of flow. And the role of the physician is to sort of tend the garden, and to tend the ecosystem. So, a lot of the ecological thinking and the tools I learned translate nicely to the model of Chinese medicine. The other places that, in terms of even the scientific investigation, ecology at its heart is multidimensional. Why does a certain plant succeed in an environment? It’s not because of just water or sunlight or temperature. It’s some complex interaction between these multiple variables. And I think the holistic lens of Chinese medicine has that same appreciation -- that we need to look at multiple variables, we need to look at how they interact in complex ways. We need to look at the system and not try to always just isolate for a single active ingredient or the single factor to treat. We treat the whole person. CURWOOD: I’m speaking with Peter Wayne, head of the research department at the New England School of Acupuncture. We’re talking about the new federally funded research program on alternative medicine in which alternative medical schools will be a full participant in the studies. Indeed, his school is leading a set. We’ll be back in a minute – stay tuned. I’m Steve Curwood and you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth. [MUSIC: The Allstonians “Alex Beam” THE ALLSTON BEAT (Moon Ska -1996)] CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood, and my guest is Peter Wayne. He heads up the research department at the New England School of Acupuncture in Watertown, Massachusetts. We're talking about a new federally funded research program that sets up developmental centers of research at alternative medicine schools. Now the goal here is to bring alternative and standard American medical practices closer together. In a moment, we'll be joined by Julie Buring of Harvard Medical School, who is intimately involved in one of these studies. But first, Peter, clue us in here. What is it about Asian medicine that really excites you? WAYNE: I’ve seen a number of my tai chi patients – in some ways, my tai chi teaching is my clinical practice – and I’ve seen thousands of students, or patients, so speak, over the years. And I’ve seen many of them benefit in ways that conventional medicine just couldn’t find the right button to push, or the right sets of buttons. One of the cases comes from our recent study with chronic heart failure and tai chi. And we were working with late stage heart failure patients, some of them waiting for heart transplants. And what we saw in just 12 weeks of very simple tai chi training – and these are very ill people – was very significant improvements in quality of life. And we also had some very objective measurements. We were able to look at exercise capacity, oxygen uptake kinetics. We were also able to look at peptides, heart peptides, that reflect heart stress. And most of these bio-markers improve markedly over just a 12-week period. Some of the other things that we saw in theses patients was, in addition to seeing these heart failure markers improve, we were seeing huge changes in quality of life. People started driving again, they drove themselves to the studies -- some of them said it was the first time they had driven in years. Their sleep patterns were better. And one woman remarked she thought of me when she woke up one morning because she hadn’t seen that side of her room in years, and she realized her neck never turned that way. And so these were some of the other things that we saw in the study. CURWOOD: One of the things about the western research method is that you want to randomize the trial, and when you have a bunch of people in the study, you really don’t want them to know exactly what’s being done. And therefore, in many cases, you need a placebo -- that is, something which they think is the treatment or medicine, but is not. How can you do this with acupuncture? WAYNE: That’s a great question. There has been a number of approaches. One of them is to put needles in acupuncture points that are not considered important. In other words, if you’re treating someone for depression, you may give them a treatment for stomach disorder. And, therefore, you’re really comparing whether the treatment for depression is more effective than a randomly chosen treatment. Another possibility is to put needles in other parts of the body -- away from any points whatsoever -- to insert them shallowly. But even there we know that just puncturing the skin can have some effect on the neural-hormonal system. Most recently a number of research groups have developed the placebo needle. It looks like it’s penetrating the skin, but really, it just folds into itself. So the height of the needle shrinks, and the patient thinks there’s nowhere else for it to have gone but into my skin and they may feel a little prick. CURWOOD: Well now, Peter, I want to bring in another person who might be considered, perhaps, your alter ego on this project. As under the structure of the developmental centers, as I understand it, the alternative medical school leads the research but must also collaborate with a conventional one. In this case, it’s Harvard. Julie Buring is an epidemiologist at the medical school there, and she’s director of research at Harvard’s Osher Institute which studies alternative medicine. And she’s joining us now – Dr. Buring, welcome. BURING: Thank you. CURWOOD: So, what’s the role that you play in this research? BURING: Well, basically, Peter and I are complementary in the doing of this development grant. We’re going to be working together to accomplish the goals and really learn from each other. And at the end that we both have grown and can do more independent research in this area ourselves. CURWOOD: What’s in it for Harvard? BURING: Many, many things. This was really a unique opportunity. When I saw the RFP -- the request for proposal that came out from the National Institutes of Health, N-CAM -- I was so excited. This is an area, alternative and complementary medicine, where there are such opportunities for research to be done in a high quality way. We already had a relationship with NESA, with the New England School of Acupuncture. We respected their work, we knew them as colleagues. This was an opportunity for us to grow in our knowledge of acupuncture and complimentary medicine, for NESA to grow in terms of their ability to be independent researchers, and for actually both of us to do better together than we would have done separately. This opportunity doesn’t come along very often. CURWOOD: One of the things that is said about east Asian medicine is that it’s ecological in its approach. And if you’re an epidemiologist, then you’re obviously interested in human ecology, under what circumstances do people respond. How much of that is an inducement to do this kind of research? BURING: I think there are incredible challenges to doing this kind of research. The principles are the same, whether I’m doing my studies of aspirin in the prevention of heart disease or we’re looking at tai chi for congestive heart failure. They’re all the same but the challenges are different depending on the intervention. When I do aspirin, I’ve got a pill. I know exactly what’s in it, I know the dose, I give it to you, and you take it. When I’m talking about tai chi, I’m trying to understand, is it the exercise component that’s making a difference? Is it the meditative component? Is it the social interaction of being together in a group to be doing this? I want to know what’s important. It could be everything because then that is what we would recommend to someone. But it might be that there’s one component that really makes the difference, and then we can recommend that. This is the difference between the kinds of things that I have traditionally done, in terms of intervention, and what we are doing now. And the challenge is very enticing. There’s no question about it. CURWOOD: So, what’s your take on the cultural divide here? What’s it like for a researcher like yourself to work with somebody who’s trained from this, well, almost entirely different system? BURING: Basically, we both understand our goals. That if there are interventions -- whether it be tai chi, whether it be acupuncture, whatever it is -- that it’s being widely used by the U.S. public. And claims are being made for it’s efficacy. Then, basically, we feel an obligation, an ethical obligation, to evaluate it. So our goals are identical. If acupuncture works in these studies that we are doing now, then we want people to know it so more people can be using it. And if it doesn’t work, we want people to know it so people will be using other alternative interventions that do work. CURWOOD: So, at the end of the day, how much of this is about money -- say coverage by insurance companies? BURING: You know, right now the majority of it is not covered. So most people are actually using these therapies on their own out-of-pocket. If it does work, though, then I believe the evidence ought to be presented just like any other therapy. In other words, we keep on talking about complementary, alternative, integrative. I believe in just coming up with the best therapies, the effective therapies. They’re only alternative until they’re demonstrated to work, and then they become just routine medical therapies that should be covered just like anything else is. So, what we’re talking about is a gradient of knowledge and proof and efficacy information. We need that. That’s what we’re trying to get to. CURWOOD: Peter, is it about money, as well? WAYNE: Well, I think that’s a big part of our medical system right now. People are spending a lot of money out of pocket. Now, actually, some acupuncture is covered under some HMO’s and health plans. And that’s partly because of the efficacy that’s been shown in certain trials. We want to know a little bit more about where it’s most efficacious, where it’s not, and to allow that industry and these organizations to help inform their decisions about coverage. CURWOOD: Julie, look me turn back to you for a moment. You know, in terms of rigorous studies, there’s very little evidence so far – some evidence, I guess, around dental pain and arthritis – that shows that acupuncture is effective. But not that much. What are your hopes for this endeavor? BURING: You know, I just want to answer the question. We keep on talking about little evidence of efficacy – in my mind, a lot of the contributions also come when something is shown to not be efficacious. It really is in both directions. And my goal completely is to answer the question definitively. That if there is something that is being used, and claims are being made, I want to contribute to the either demonstrating the efficacy, or clearly demonstrating that there is no efficacy. Or, if there’s efficacy, I want to show the side effect profile. Because if you’re a healthy person who’s really using this to prevent disease, or a wellness kind of situation, you want to know what price you’re going to pay in terms of possible side effects. All of that is very important to show, and I would consider that a true goal of this collaboration. CURWOOD: You have three studies that you’re working on in collaboration. One involving trying to boost the white blood cells of women getting chemotherapy for ovarian cancer; another looking at reducing pain in endometriosis in young women. And the third study is, Peter? WAYNE: It’s a methodological study that centers around how we do a diagnosis in Chinese medicine, and whether we can develop an instrument for intaking that information in a training system, that makes it more likely for practitioners to come up with the same diagnosis. To be more accurate, to be more reliable, to be more valid. As much as the diagnosis – as central a role as it plays in our medicine, in studies where we have used that, in many cases there are huge differences between practitioners diagnosing the same patient. And so for the credibility of Chinese medicine to grow within the context of clinical trials, we need instruments and tools that are valid, that are reliable, that are repeatable. CURWOOD: Well, you’re talking about really changing, then, the discipline. I mean, it sounds to me today that if I were to go to an east Asian practitioner, that Mr. Lu would say I have this, but Dr. Wong might say I have that, Mr. Li might say something else, and so on and so forth. Whereas in the west, you typically would expect to have a single diagnosis --or a pretty good fight if there was a disagreement about it. WAYNE: Although I would say that there are many conditions, particularly chronic conditions, where a diagnosis is not that obvious to the traditional, conventional medical community either. CURWOOD: But if this works, you’re talking, really, about a substantial change then, in East Asian medicine. WAYNE: Yeah, it’s partly a cultural shift. How can we bring the rigors of science to the tools of East Asian medicine? I mean, they need to stand up to the same standards. CURWOOD: I want to turn for a moment to the studies on women, in particular, the one on ovarian cancer. Now, as I understand it, this is a phase two trial which means that you’ve already had some results. What are those results? BURING: Well, enough to know that it is promising. Enough to know that the acupuncture has evidence that it could be beneficial. But not enough to have demonstrated that definitively, and that’s what we need to do. And see if it makes any difference what exact therapy was given so that it can be reproduced. And if I can add to what Peter just said, I think the biggest issue that we are working through is a need to describe in detail the therapy that is being given so that it is reproducible. Not to make it standard, not so everybody has to do the same therapy, but to put it in a way that we understand what is being done so someone can learn from it and replicate it. And that has been the very hard one in a field where so much is art, so much is individuals. And there is a real art to doing this. But we have to be able to write it down. We need to write the methods section of the paper, we need to tell people what is being done. And that’s been very difficult, too -- a cultural issue that needs to be dealt with. CURWOOD: Although there are a lot of things that we don’t know the methods on. For example, for years the tobacco industry argued that we didn’t have the exact mechanism linking the use of tobacco to cancer, and, therefore, it wasn’t a problem -- even though it was pretty obvious that there was some kind of a link to people pretty early on. So, could we get hung up a little bit trying to find these details and kind of miss the big picture if we’re not careful? BURING: I think you’ve got a good point but there’s two different things we’re talking about here. One is understanding the mechanism by which acupuncture could exert its beneficial effects. And you’re absolutely right, we may be years from understanding that. We may be able to see its efficacy long before we can understand the mechanism. What I’m talking about, though, is when I say that acupuncture works, what’s acupuncture? What are the components of it that make a difference? So that when I go to another person and say I want acupuncture, I want this that works – what is it that we just tested? CURWOOD: So, Dr. Buring, what’s it like when you get a bunch of acupuncturists and traditional MDs in the same room to do this kind of research? BURING: There’s no question that we come in with a feeling of excitement and a feeling of trust. And we have to work through the cultural aspects. We were just coming from different directions. But please never misunderstand, it is no different from putting physicians and surgeons in the same room and trying to work out a trial, as putting an acupuncturist and an epidemiologist in the same room. We come from different places, our culture is different, we have to get to know each other, we have to get to trust each other. And that takes a while no matter who the people are. CURWOOD: Now, when it comes to the faculty development – and part of your work here, I gather, is that you are teaching practitioners – who’s teaching whom? BURING: I think this has been different from any kind of mentoring or teaching I’ve ever done, and I’m very committed to it. It really is bi-directional. It’s more like being big brother, big sister than it is the traditional mentoring. And at the end of it, we both will have grown and we will both be doing independent work. But I hope we’ll be doing collaboration forever. CURWOOD: Peter? WAYNE: I think the Osher Institute and other institutes at Harvard have a commitment to CAM therapies, and to understanding them. But they really need to engage seasoned practitioners with clinical and theoretical knowledge, to fully understand those medicines and figure out how to do research in those areas. So I think they’re learning. We’re learning about the practice of scientific research. And there’s a lot of other practical things that go into having a research program. One of the components of the mentoring that the Harvard institutes are giving to NESA has to do with grants management. There’s a tremendous amount of administrative aspects of developing a research program. There’s the protection of human subjects with institutional review boards. And so for each phase of each component of this research program – not just the scientific component, but administrative, budget issues, etc. – we have mentors. And so there’s a relationship at multiple levels of the center. CURWOOD: I’ve been speaking with Dr. Peter Wayne who’s head of the research department at the New England School of Acupuncture, in Watertown, Massachusetts, and Dr. Julie Buring who’s an epidemiology professor at Harvard Medical School and director of research at Harvard’s Osher Institute. Thanks for joining me today. WAYNE: Thank you. BURING: Thank you very much. [MUSIC: Tracy Scott Silverman “Improvisionation with Overdubs” TRIP TO THE SUN (Windham Hill Records - 1999)] Related links:

CURWOOD: If you like hiking and adventure, if you like breathtaking scenery and the excitement of seeing big and little animals up close in the wild, then I have a last chance invitation for you to join me beginning May 1st on safari in Africa. MUSIC UNDER AND OVER: [Kronos Quartet “Escalay (Waterwheel)” PIECES OF AFRICA (Elektra - 1992)] CURWOOD: We’ll start in Kruger National Park in South Africa, hiking during the day and heading out by four-wheel vehicle at night. We can expect to see anything from baby elephants nursing to leopards on the hunt, and experience the big sky and powerful quiet of the bush. And just when we think there could be nothing more like Eden, we’ll head down to the wild coast of Africa on the Indian Ocean to hike, paddle and ride horses along remote estuaries and beaches. This part of the safari will be led by the AmamPondo people, who are devoting their lands to eco-tourism instead of the mining operations that threaten this pristine habitat. Accommodations will be in simple camps that tread lightly on the land. There are two ways you can join me on this caravan. You can win a trip, or guarantee a spot by buying a ticket now. The details are the living on earth website – that’s livingonearth.org. But don’t dally. The eco-tour is just about full and this is the last call. That’s livingonearth.org for the African Safari with me, Steve Curwood CURWOOD: Coming up: a town faces extinction in the face of a drive to create more wilderness. You’re listing to NPR’s Living on Earth. ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation. Major contributors include the Ford Foundation, for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, and the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund. Support also comes from NPR member stations and the Noyce Foundation, dedicated to improving math and science instruction from kindergarten through grade 12. And Bob Williams and Meg Caldwell, honoring NPR’s coverage of environmental and natural resource issues. And in support of the NPR President’s Council. [MUSIC: Greyboy “Panacea” GET SHORTY SOUNDTRACK (Polygram Records - 1995)]

Portrait of a Shrinking TownCURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood and coming up -- the songs of winter. But first, just northwest of the New York-Pennsylvania border lies a town in the midst of a forest. It’s just three miles from the Southern Tier Expressway, but it might as well be three thousand. Because when you get off exit 20 and drive the gravel road to the town of Red House, you leave the rest of the world behind. Today, only thirty-eight people live in Red House, and the number gets smaller as the years go by. Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu visited this shrinking little town and spoke with some of the residents about a deal made thirty years ago that sealed the town’s fate. [GUITAR STRUMMING] FRANCE: [SINGING] Left the [inaudible] at Red House, on the river oh so fine, climbed the hills of bay state, my that was quite a climb… CHU: Lewellyn France sits in his favorite armchair, with his dog Moose at his feet. He’s singing a song about the history of his town -- a town that grew up around a river, a railroad, and a little red house, more than 150 years ago. FRANCE: [SINGING] It’s the story of a loggin’ railroad, called the Allegany & Kinzua… CHU: Back in the mid-1800s, rafters would guide their boats down the river, carrying lumber from the forest to the timber mills downstream. Where the river met a small brook, they would stop at a little red house on the riverbank for some food and gossip. As the timber industry flourished, so did the population of the land. A railroad replaced the rafters, and the little red house lent its name to a bustling timber town.

FRANCE: Oh yeah, it was a busy place. It was really a booming place. I think my grandfather said there was five hotels at Red House Corners down here. CHU: Lewellyn, or Hook, as his friends and family like to call him, is the highway superintendent and unofficial town historian of Red House, New York. He was born and raised in a farmhouse down the road. Hook is 72 years old, and is the third generation of Frances to live on Red House land.

|