Do Aliens Speak Physics?

Air Date: Week of January 30, 2026

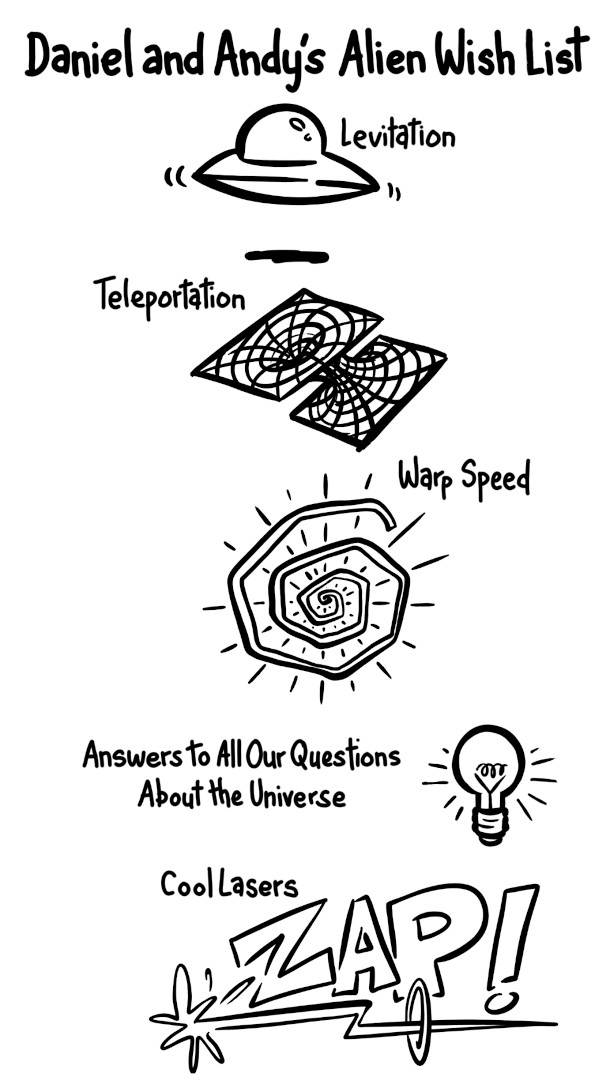

Written by Daniel Whiteson and Andy Warner, “Do Aliens Speak Physics?” questions the universality of physics and science, blending humor and philosophy. (Image: Andy Warner)

Classic science fiction tends to assume that if aliens visit Earth, they will have done so thanks to using math and science that’s like our own. But physicist Daniel Whiteson and cartoonist Andy Warner aren’t so sure. They speak with Host Steve Curwood about their book Do Aliens Speak Physics? And Other Questions About Science and the Nature of Reality.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

In a classic science fiction film, A UFO Lands, soldiers and scientists swarm the craft, and after some confusion, a political crisis or two, and a romantic subplot, there comes the “ah hah!” moment when the beings reveal some key secret of the universe that saves or destroys humanity. But physicist Daniel Whiteson and cartoonist Andy Warner doubt such a scenario. They’re the authors of the book Do Aliens Speak Physics? And Other Questions About Science and the Nature of Reality. In their minds, we can't assume our mathematics and chemistry will make sense to visitors from another planet or star system. To ask these questions, Whiteson and Warner took their scientific and historical knowledge and combined it with their love of dad jokes and donuts to write a book about what ETs might teach us about living on Earth. They join us now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

WHITESON: Thank you. It's a pleasure to be here on Earth.

WARNER: Yeah, at least for now.

CURWOOD: Well, it is one of the better planets, isn't it?

WHITESON: It's the coziest planet we have found so far, for sure.

Daniel Whiteson is a professor of Physics and Astronomy at University of California, Irvine. He is interested in using machine learning to understand particle collisions. (Photo: Courtesy of Andy Warner)

CURWOOD: So let's start with you, Daniel, this book asks such a broad range of deep philosophical questions, covering everything from whether math is real to whether science is necessary to develop technology. So what inspired you to write such an expansive book?

WHITESON: Well, the reason that I got into physics, originally, as a young kid interested in many broad questions in science, was its universality. It seemed to me that physics was about more than just questions about life here on Earth, or, you know, geological formations under our feet, that it asked questions that apply to the whole universe. How big is the universe? What is it made out of? How did it begin? These I thought were questions that would be asked on Earth and also asked in around Alpha Centauri and in other galaxies. And I fantasized about one day meeting those aliens and going to an interstellar or intergalactic physics conference and connecting with them about this. And this is a theme you see in science fiction all the time that you meet an alien species, and you use math or physics to connect with them because it's surely something we will have in common with aliens. But, as a professor here at UC Irvine, I often spend some time in the philosophy department, where they welcome random people to come into their seminars. And I was surprised to learn that philosophers are much more skeptical of this notion, this fantasy that physicists have, that the way we describe the universe is the only way to do it, and that aliens must arrive at similar structures and similar mental concepts to tackle these broad questions.

CURWOOD: Big questions, indeed. And hey, I understand that, Daniel, you reached out to Andy to illustrate this book. What drew you to his work?

Andy Warner is a writer and cartoonist. His work has been published everywhere from Slate and Popular Science to The Center for Constitutional Rights and UNICEF. (Photo: Courtesy of Andy Warner)

WHITESON: Well, this, as you say, is sort of a weighty topic, but it's also a lot of opportunity for humor. And my strategy when digging into these questions is to balance big ideas, deep concepts with jokes because your brain needs a break sometimes, and I like an interplay between text on the page and visual elements, if it makes for more of a conversational back and forth. And so I was a fan of Andy's work. I've read his nonfiction comics for a long time. And so, I reached out to him and said, "Hey, you want to write a book about aliens?" And I was worried he would think I was a random internet crackpot, but I'm sort of a non-random internet crackpot. So I was very glad that he answered my message.

CURWOOD: So Andy, what was your first reaction when you opened Daniel's email?

WARNER: Well, once I figured out that he was not an internet crackpot, it was yes. I mean, imagine getting approached by a physicist to do a book about aliens. It's a dream. My work delves into all sorts of different ideas, different places, and a lot of it is science. I'm the child of scientists. I grew up on marine biology research stations. And so the idea of taking this really weighty topic, like the philosophy of math, the philosophy of science, and then using aliens, and especially using kind of the way that aliens might have evolved in contrast to us? I mean, I was hooked from the first paragraph. A pitch like that is really hard to say no to. And then emailing back and forth with Daniel, it immediately became apparent that not only did he know his stuff, but he's really funny, easy to work with. We just got off to a roaring start, pretty much from the get-go, I would say.

CURWOOD: By the way, there's a theme in your book: donuts. Talk to me about why you bring the donut machine into this discussion.

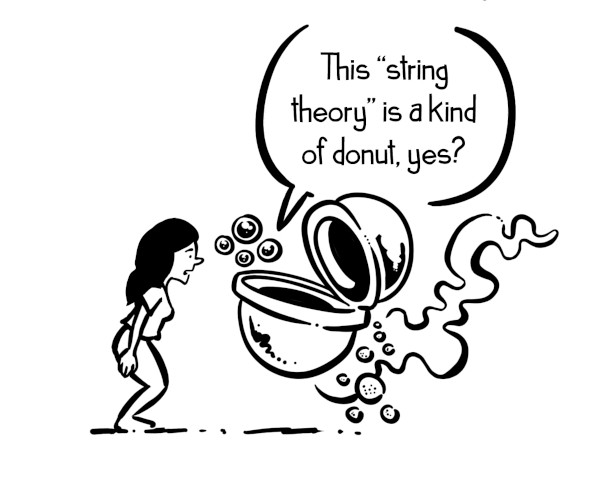

Through humorous cartoons, the writers make difficult physics, science, and philosophy topics accessible. (Image: Andy Warner)

WHITESON: Well, you know, we like to balance deep ideas with silly concepts and jokes. It's actually a lesson I learned in an essay from one of my favorite human writers, Dave Barry, who said that, look, some words are just funny and you should work them into your writing, words like weasel or booger. And so we tried to use the word donut as a theme. And it actually is quite helpful in some cases. For example, we're imagining how one might reverse engineer a donut machine, what's going on inside the machine, as a metaphor for trying to understand the universe. We are experiencing the universe. We are trying to reverse engineer its fundamental workings. And we and aliens might come up with different explanations for what's going on behind the scenes, in the same way that two engineers given a crazy donut machine might come up with two different ways to imagine its internal blueprints.

WARNER: I have a distinct memory of during the editing process going through and replacing various nouns with the word donut.

CURWOOD: Now, you assume that we haven't made contact with aliens yet. What if they're here now, but they don't want to say?

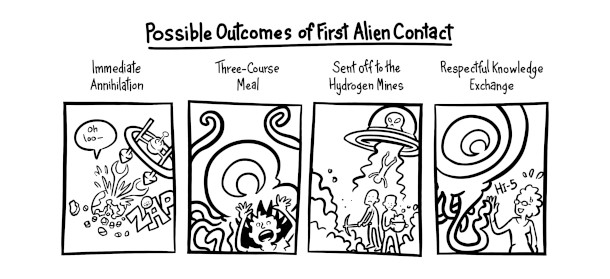

For the writers, thinking about aliens became a way to investigate deeper questions about how humans understand the universe and how science develops. (Image: Andy Warner)

WHITESON: That's certainly possible. And there's lots of creative theories you could have about various aliens that have found us and don't want to communicate with us, or already here or dropped off instructions for building pyramids 1000s of years ago, etc, etc. But, you know, there's no evidence for that, and so it's hard to know how to proceed with a theory like that without any concrete evidence. I imagine instead, the scenario where aliens show up and they want to talk to us. They want to communicate with us. They land in Central Park and they are ready to have a conversation because, otherwise, I don't know how we get started with a conversation with somebody who doesn't want to talk to us.

WARNER: One of the things that initially grabbed me about the book — and I think that kind of answers your question a little bit — is that it's about aliens, but it's also really about these deeper questions, right? The aliens are a way to get at the questions that's like fun and inviting and draws people in because it lets me draw really big boopy monsters in all these different fashions. But the book is really about the way that we are thinking about the universe, thinking about ourselves, the way that science develops, and the aliens is a doorway into those questions. And so, you know, it's sort of a broader question than why would they not talk to us? It's, could they talk to us if they wanted to? It sort of pushes it past that.

CURWOOD: All right, you have many fun questions in this book, and one of your chapters, “Can Aliens Taste Electrons?” explores what senses aliens may or may not have. I mean, how might an alien species sensory experience influence their scientific process, do you think? Assuming they have a scientific process.

Do aliens have the same five senses as humans? Do they share our curiosity traits? Those are some of the questions the book asks about aliens. (Image: Kevin Dooley, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

WHITESON: Yeah, it's a really fun question. On one hand, you might say, "Look, we have a base sense of ways to interact with the universe, our five senses, but we've augmented those. We have gone beyond the limit of our eyeballs. And we have infrared telescopes. And we can detect dark matter and neutrinos and all things that our ancestors never could have interacted with." So that might lead you to assume that any technologically advanced civilization is going to end up experiencing the full sense of the universe, and we can talk to them about all of these things on a level playing field. But I think that misses something really important, which is that, while we extend our senses technologically, we always end up translating those new experiences back into an intuitive language of our minds. Like, when the James Webb Space Telescope takes a picture in the infrared, they don't show it to you in the infrared. They color shift it into the visible spectrum, so that you can see it. And when we measure gravitational waves, ripples in space time, they translate those into sound waves so you can hear it. And that's because we tend to think in a certain intuitive language that I think is strongly influenced by our biological senses. We are visual. We are auditory. We are sensory in the ways that our biology sort of defines. So I think that aliens, if they start out with a different fundamental set of senses, because their evolutionary situation is different, they could have a different sense for what makes sense to them. Even if they have technology to go beyond their senses, their mental language might be fundamentally incompatible with ours. Some explanation that makes sense to us because it's visual in some clever way that clicks in your mind might make them go, "Huh? That doesn't make sense at all."

CURWOOD: So, Andy, you've written a lot about history of science, and of course, a large part of that history and what indeed guides human science is curiosity. A lot of the discussion in your book around the first contact assumes that the aliens are going to be curious, just the way we humans are. But I'm not sure your book really supports that. Talk to me about it.

The book hypothesizes over what contact between aliens and humans could be like. In one of those scenarios, extraterrestrials might answer scientific mysteries related to gravity, black holes, and time, for example. (Image: Andy Warner)

WARNER: Yeah. Curiosity is foundational to how we do science. It's really what drives humans to explore different directions. And the idea that science is this path, this singular path that moves in one direction, is false. It's more like a river with tributaries and waterfalls. And the way that human science moves forward just by human fixation on something, like one person becoming really, really into something, and then, frankly, devoting their life to something that might seem trivial to another human is one of the main drivers as a collective unit of what pushes us forward, or pushes our science forward. And a lot of it comes down to our basic human fascinations. What are humans interested in? Even things like our basic anatomy, the fact that we walk around on two legs and so our neck cranes up, that makes us interested in the stars, right? We were putting together constellation theories long before we even realized anything about what they were about. And so, the way that our basic anatomy, the way that our brains work, our hands work, our eyes work, actually governs the way that our science is put together, patchwork by patchwork in this big quilt. And you don't even know what's in between one patch and another. Maybe it's a formless void and you can't stitch it. We don't know that yet, but those patches will be different with any other intelligent species. I mean, they would be different for dolphins and dogs, and we evolved alongside them. I mean, frankly, we evolved dogs for us, right? But like a lot of where science takes us is based around us. It's based around our very humanness. And humans are curious. We don't know if other aliens will be curious, or if they are curious, in what way they will be curious.

CURWOOD: There's one topic you don't really have in your book. But if I had aliens and they were willing to talk to me about things, I might ask, "How does consciousness fit into our understanding of existence, this universe?" What might they say if they're willing to talk to us about it?

WHITESON: Yeah, well, they might start by saying, "Well, what do you mean by consciousness, exactly?" That's the way all philosophical conversations end up, disagreeing about terms. It's a really hard question, and it's a great example of something we have not been able to tackle. We have no scientific explanation for why you are having an experience right now, why you have a rich internal life. There is no explanation for that. And we don't know how, for example, tiny particles, “to-ing and fro-ing,” at the most basic level, somehow work together to emerge, to make our universe and classical physics and our experience of music and all this kind of stuff. We cannot explain that. And some philosophers I talked to said, "You know, that maybe we're just going about it the wrong way. Maybe it doesn't emerge from the microscopic “to-s and fro-s” in some complicated way we haven't figured out yet. Maybe it follows its own rules, right? Maybe there aren't rules only at the most basic level, and then everything bubbles up from that. Maybe every level of the universe, hurricanes and brains and particles, has its own set of rules." That flies in the face of sort of the traditional approach of Western science, reductionist approach, to go from the bottom up, but philosophers are much more willing to consider what you might think are crazy ideas. You know, that's not ruled out. It's certainly possible. It's consistent with everything we see out there in the universe. And so consciousness is a great example of a problem that we have not been able to solve, and it may be that the whole approach that we're taking is not one that's going to lead to an answer.

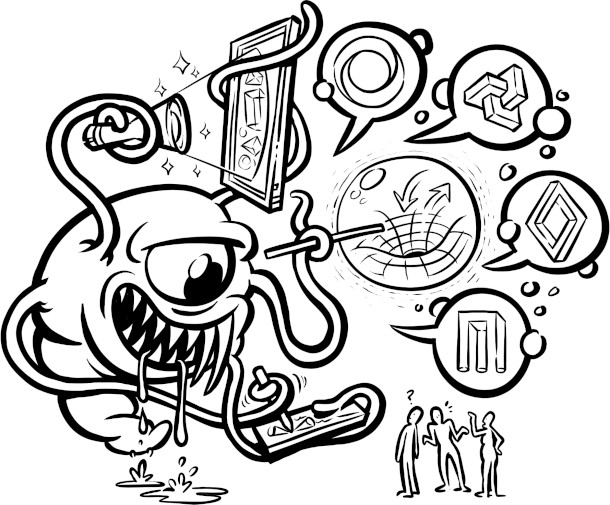

Warner and Whiteson also propose that ETs might help us learn a lot more about what it means to be human and how our curiosity has propelled our discovery of the universe. (Image: Andy Warner)

CURWOOD: So let's say the aliens were here to teach us a bit about things. What might they tell us about things that have us scratching our heads, like time and gravity?

WHITESON: Yeah, great question. One of the possible scenarios for aliens arriving is that they are doing science the way that we are, that there is one path through science. Daniel's original dream comes true, where we get to be like educated by super advanced aliens. And that's so exciting because there are so many big questions that are open in our understanding of the universe. You know, how big is the universe? Is it finite, or is it infinite? What's inside a black hole? Why does time flow forwards? These are questions that, like everybody wants to know the answer to because they're really basic questions about the nature of the universe we live in. It's sort of shocking that we don't understand them. You know, we might, in 1000 years, figure them out, and then look back at this time and think, "Wow, what was it like to be so ignorant, to live in a time when you didn't know the answer to these like, fairly basic things about the nature of your own existence." And so it's exciting that aliens could show up, and they just know these answers that we don't have to struggle for 1000 years, and they could just deliver them to us, and we could leap forward into our scientific future. And I'm not arguing against that. I am all for that, and I want to be on that mission to go talk to the aliens and get up at the chalkboard with them and their tentacles. The book is about tempering our expectations because it could be that what we learn is not just about super advanced science and quantum gravity and all sorts of stuff about the way time works. It could also be something about ourselves, about the human lens through which we've seen the universe, and how that has colored our expectations and our explanations. And that's not supposed to be a downer. That's just another thing we might learn. It might be just as revealing and just as fascinating as learning the secrets of quantum gravity.

CURWOOD: I want to look at this from a slightly different angle. What do you think is the biggest false assumption that people have made when thinking about first contact with aliens?

The book challenges readers to take a more expansive approach to science, considering what might happen if we consider the universe from different vantage points. Shown above is a circular representation of the observable universe, shown on a logarithmic scale, with our solar system at the center and enlarged images of various celestial objects. (Photo: Pablo Carlos Budassi, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

WHITESON: I think a major theme in alien contact stories is that we get a message from space, not that aliens have arrived, but that we receive a message from them, and that we sit down and puzzle over it, and crank it through the computers, and we decode it, and we understand what it means. And, if you talk to linguists and philosophers of language, they all think that's probably impossible because every time you get a message, anytime you communicate, you're taking this step where you have your ideas in your mind and you transform them into symbols, which you can then communicate, and then the person at the receiving end transforms those symbols back into ideas. If it's a language we both understand, that works really well. And if I'm thinking in a way that you might be able to understand, but I write in code, you might be able to figure it out. You might be able to crack that code by thinking through the various possibilities. And when you get it right, you can see my original idea, right? It makes sense to you. But if you are talking to an alien intelligence that's thinking things that might be very, very alien, and using some other way to transcribe those ideas into symbols, the chance that you're going to figure out how to reverse that encoding without their help and recognize when you figured it out, seem very, very slim. And even the much simpler task of understanding human languages from ancient civilizations that are long gone, we don't have a great track record there either. I mean, we decoded Egyptian hieroglyphics, but only because we got this amazing cheat sheet, the Rosetta Stone, and it still took 20 years. And we never decoded Etruscan or other human languages. So the chances of getting an alien message and decoding it, I think, are quite amplified in science fiction, which is why in the book, we focused instead on the scenario that the aliens arrive, and they can help us actually build communication by having a context in common, by pointing at donuts or dolphins or apples and learning the symbols for those together.

WARNER: Yeah, just to jump on that, one of the things that Daniel does best is to always turn this around and look at it from a human perspective. And so we have tried to send those messages out into space, right? We've done the opposite, and we have a pretty poor track record of that. Not to dump on Sagan. I love Sagan, but the Golden Record, one of the interesting things is that Pluto's in it, right? So it's a map to our solar system that involves this definition of a planet that we no longer agree on, even after we sent out the Golden Record out. So it's not only is any attempt at communication from a long distance, a difficult code, but it's also a snapshot in time, right? And that may radically change by the time it gets any attempt at decoding it.

CURWOOD: Andy, by the way, you refer to the Golden Record that was put, I think, on the Voyager spacecraft, yes?

WARNER: Yeah, yeah.

CURWOOD: Actually, on both of them, right? And there were all kinds of interesting recordings from Earth at that time. Remind us of what's in it.

WARNER: Sure. They put music on it. There's pictures of your standard male and female human, which just so happened to look very like European clothing models. There's a map to Earth, useful for any future alien invasion. There's a hydrogen atom. There's, what they say is, the brain waves of, that they recorded when they told a woman to think about love. But we can't actually read minds, so we don't know what she was thinking about.

WHITESON: Maybe it was donuts.

WARNER: Maybe it was donuts. It is a real record, and it is really made out of gold, and we did really send it out into space.

The book features over 300 black and white illustrations. (Image: Andy Warner)

CURWOOD: So let's zoom out. What can we learn about ourselves by thinking about aliens?

WHITESON: I think that by thinking about aliens, we can start to understand the way our culture or our biology, or something about our human nature has affected the way we explain the universe. And even without the aliens coming, I hope that that gives us an opportunity to take a second look at those assumptions and wonder, is there another way to do this? Can we break out of our assumptions and think about other ways to explore the universe that might help us understand things that have remained understandable to us? Science shouldn't just be one thread, and isn't one thread, but it should be broad, and we should consider explanations from all various angles because we don't know which one is going to be successful. So we hope, by writing this book, we help people crack some of those assumptions and think about the universe from lots of different angles, as Andy says, "We should be our own aliens."

CURWOOD: And then Andy, what's the benefit of us thinking differently then? What's the dividend that we reap from going through this process?

WARNER: Well, again, it's curiosity, to come back to that foundational thing that makes human science human, that makes humans human. It inspires greater curiosity. It sparks us to push into new places that two generations ago would not have been dreamed of. There's all these moments in human history where somebody leaves something in a drawer, and it gets exposed to a chemical, or somebody has a conversation, and it sparks a little bit of imagination, and the arc of science as we understand it changes. And it takes a while for that arc to change. There's a lot of arguments and stuff like that, but a lot of this comes from just moments of human curiosity, and that curiosity comes from thinking in different directions than you would expect to, to explore the unexpected. That’s what we hope for.

CURWOOD: Daniel Whiteson and Andy Warner are the authors of Do Aliens Speak Physics? And Other Questions About Science and the Nature of Reality. Thank you both for joining us.

WHITESON: Thank you very much for having us on and for the great questions.

WARNER: Thanks, Steve.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth