October 22, 2021

Air Date: October 22, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Carbon Offsets and Illusion

View the page for this story

More than 170 major companies have pledged to become carbon neutral by 2050, with many counting on carbon offsets and carbon trading programs to help them reach that goal. But critics say these offsets are often hard to verify and can give these companies a license to continue to pollute. Among those critics is Jennifer Morgan, the Executive Director of Greenpeace International, who joins Host Steve Curwood for more. (10:17)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb dive into how the global supply chain disruptions could create herbicide shortages in 2022 and discuss the benefits of growing crops under solar panels. And from the history books, they look back to 1936 when the first electric turbines at the Hoover Dam went into service. (05:12)

Right Whales Struggle to Grow

View the page for this story

North Atlantic right whales face a number of threats from climate change, vessel strikes, and entanglements in fishing gear, and scientists estimate that fewer than 400 remain. Now researchers have discovered that because of these stresses, the whales are smaller than they should be and that could be leading to fewer successful births. Study co-author Amy Knowlton of the New England Aquarium speaks with Host Bobby Bascomb about what people can do to help this critically endangered species. (07:58)

King Penguins Entering Surf

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

On the coast of South Georgia Island in the Antarctic Ocean, Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender watches as a colony of King Penguins plunge single-file into the surf to feed. (02:28)

C’waam And Koptu: The Fish at the Center of the Klamath Basin’s Water Crisis

/ Erik NeumannView the page for this story

In the drought-stricken Klamath Basin along the California-Oregon border, water is a precious resource. Who gets that water hinges, in large part, on two endemic species of fish that make their home there and nowhere else in the world. Jefferson Public Radio reporter Erik Neumann reports. (04:39)

A New African Voice on Climate

View the page for this story

Countries in the global South are among the least responsible for causing climate change compared to the global North but are among the ones suffering the most from its effects. Vanessa Nakate, a young climate justice activist from Uganda, is an advocate for the underserved communities who are the most affected by climate change. She joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about her book A Bigger Picture: My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis, in which she points to how the climate crisis is impacting Africa and the discrimination she’s faced in speaking up. (16:24)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

211022 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Amy Knowlton, Jennifer Morgan, Vanessa Nakate

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender, Erik Neumann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Greenpeace calls for an end to trading more carbon credits.

MORGAN: It allows those who should be reducing emissions at source, to go and plant trees somewhere? Sorry, especially in times when land grabbing is huge, indigenous rights violations are massive, and biodiversity loss is big? No time for that.

CURWOOD: Also, scientists find that North Atlantic Right Whales are not growing as large as they should.

KNOWLTON: What we found is that the average reduction in length is about 3 feet when they reach their full length. So, 3 feet shorter than they were back in the early decades of our studies in the 80s and 90s. So, that’s a pretty dramatic reduction in size.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Carbon Offsets and Illusion

Critics say that carbon offsets give can companies a license to continue polluting activities with an illusion of making progress fighting climate disruption. (Photo: Alex Hamilton, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

As the nations of the world prepare to meet at the UN climate summit that begins on the last day of October in Scotland, more than 170 companies are pledging to become carbon neutral by 2050. Corporations including Amazon, Shell, and GM are counting on carbon offsets to help meet their climate commitments. The companies say offsets help them protect the climate even as they continue to emit greenhouse gases because they are paying to reduce emissions elsewhere. Carbon trading programs with hard caps established years ago have had some success, such as the regional greenhouse gas initiative in the Northeast US which achieved a 35 percent reduction of emissions from power companies over the last 12 years. But critics say too many proposed offsets today involve claiming emission reductions that are hard to verify, such as paying to protect and replant tropical forests. Those critics include Jennifer Morgan, the Executive Director of Green Peace International who says net-zero pledges and offsets cannot replace needed reductions and fossil fuel phase-outs to address the climate emergency right now. She’s on the line now from Berlin. Welcome back to Living on Earth Jennifer!

MORGAN: Great to be with you. Thanks.

CURWOOD: You've gone on the record saying that carbon offsets are not going to get the planet to where it needs to be in time to keep a livable civilization here. What exactly are you saying?

MORGAN: I'm saying that right now in the year 2021, where we need to have a halving of global emissions by 2030, that there is no time for companies or countries to use offsets. Because offsets are really just an accounting trick. If you think about it, like a company like Shell, it says it's going to reduce its emissions to net zero by 2050 but it wants to continue to increase its sale of fossil gas, and it wants to do so by planting trees somewhere, large number of trees that would absorb the carbon from that drilling for that fossil gas. That doesn't add up, it allows those who should be reducing emissions at source in their companies shifting their business models to go and plant trees somewhere. Sorry, especially in times when land grabbing is huge, indigenous rights violations are massive and biodiversity loss is big, no time for that.

CURWOOD: Well, now they would say math is math. If the trees take the same amount of carbon out of the atmosphere as the companies are emitting, at least that's keeping things level and if the trees take out more than that is reducing emissions. And you say?

MORGAN: I say a few things. First of all, there's a big difference between carbon that's stored underground that's been there for millions of years and carbon that is stored in trees. You know, once it goes it's just much less certain that it's going to stay there, if it's underground it's underground, if goes into a tree it could burn down, it could get cut down. Similarly, when you release those emissions from underground from coal or oil, you know, those emissions are out in the atmosphere, it takes a long time for some trees to grow. And also, there's this question of what's called permanence, how long is the tree going to stay around? And also additionality, how do you know that those trees might not have been cut down or grown anyway? And then the final thing of leakage where you know, something could move into another piece of land. These technical issues have been around since Kyoto protocol in 1997 and have not been solved. So, lots of evidence on this from many studies, that it hasn't worked. So, I'm not sure why we're doing it again now, except that I think oil companies maybe feel a bit of pressure and are looking for an out instead of having to change what they need to do.

CURWOOD: So, some criticize the notion of a carbon tax saying that if you tax something that legitimizes it, so that would actually encourage the fossil fuel companies to keep on going, knowing that it just means they're gonna raise the price. So maybe it'll reduce a little demand, but basically they can stay in business. And you say?

Carbon capture activities like planting trees can be difficult to verify and might not absorb as much carbon as claimed by sellers of offsets. (Photo: Lawrence Aritao on Unsplash)

MORGAN: I say that if carbon taxes and pricing carbon were so effective right now, then we would have seen quite a lot more of emission reductions around the world. It's really not discernible. And also, I think it's really important to bring in the social dimensions here. Because if a company can, you know, have to pay more because there's a carbon tax or there's a carbon price, where is that higher costs get transferred to? But oftentimes it will get transferred to a consumer and that consumer probably doesn't have as much money as that Corporation has to deal with this. And so that's a hugely important issue that needs to be also part of this policy mix. It's just not that simple. And I think it really hasn't worked. The level of pricing that scientists are telling us is necessary in order to really get the scale of the emissions down, well those have to be coupled with those social measures or else you penalize the wrong entity or person.

CURWOOD: Yeah, we certainly saw when Macron tried to raise the price of fuel in France, you had the whole yellowjacket rebellion. People can't afford it, especially if they don't make the money that the folks in the fossil fuel executive suites make.

MORGAN: Well and they shouldn't have to, they haven't caused this problem. Those responsible for actually causing these emissions are those carbon major corporations and the large major emitting countries around the world. And so, I think there's no climate justice without social justice, these have to come hand in hand together. And I think it's often a kind of a move, as Exxon recently said in investigative journalism thing. Yeah, we'll support a carbon tax because we know it's never going to happen. And also, they know that the social unrest will happen unless you really think of those two things together.

CURWOOD: Now, some argue that we need to halt deforestation around the world in the tropics especially. And that perhaps carbon offsets can be used for better good for those kinds of projects. What do you think is the solution to stopping the destruction of the tropical forests that are so important to maintaining the carbon balance?

MORGAN: Well, this is an incredibly important issue, I think, you know, one key thing is in those countries to have really watertight domestic laws, and policies, which protect forests, and you know, also eliminate deforestation through supply chains, and really start also to phase out industrial meat and dairy. You know, a big check coming in from corporations around the world for carbon offsets isn't going to sort it. You need these policies, you also need a just transition for those who do live on the land and do need to make a living, because if they've been doing that for their lives, well, what are the alternatives for them to find other sources of income? Again, we need to be thinking about the social and the environmental issues together.

CURWOOD: How much trouble are we in right now about the climate?

Jennifer Morgan is the Executive Director of Greenpeace International. (Photo: Courtesy of Greenpeace International)

MORGAN: We're in big trouble, Steve. We are, I think backs to the wall because so little has happened when we knew it. I mean, the first scientific study I know about was put on Lyndon B. Johnson's desk a long time ago. There's been a lot of denial out there by fossil fuel interests to slow things down to the point that we are now I mean, think about what's just happened in the previous months. And the suffering that's happened, people from extreme climate events all around the world and developed countries are now feeling it, what developing countries have been feeling for years. So, it's serious. I mean, it's scary serious. So that's why all of the movements and the youth and the people who get it and are engaging that's real, they get it, they know what their future could look like if we don't turn this around now.

CURWOOD: For 2015, the US and China got together in advance of COP21 to work out a game plan to have the Paris Climate Agreement happen. This time around, it doesn't seem to be the case that these two countries, the two biggest emitters on the planet, are working together to come up with a plan to move things forward. What are the prospects do you think for this upcoming climate meeting in Glasgow considering those circumstances?

MORGAN: Well, I think that the prospects for the Glasgow meeting are all to play for. I think that there are big expectations both for the United States to finally put a credible implementation plan on the table that goes into law that can build the confidence of other countries that the US isn't just going to come and go based on its latest election. And I think, you know, China and other countries leaning into their own national interests and peaking emissions earlier, reducing emissions domestically from coal, those are all part of the mix. But I think the real question for me is, will not just those two countries, but all of those major countries really come together in an unprecedented way that we've had before. It's no longer just about two countries, it's a bigger piece. And also, we're in a moment when movements around the world are so active in calling out their governments, and so they can jump together. You know, if they all agree, we're going to shift into no new coal, no new oil or gas mines, no new gas projects, no new funding for those. If the corps were to do that together, it would transform. And that's what's on the table here and that's what's needed, that's what people are looking for right now.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Morgan is the executive director of Greenpeace International. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

MORGAN: Very glad to. Thanks.

Related links:

- Greenpeace | “Why Net Zero and Offsets Won’t Solve the Climate Crisis”

- BBC | “Climate change: Carbon emissions from rich countries rose rapidly in 2021”

- Economic World Forum | “Why carbon offsetting doesn't cut it”

- More from Jennifer Morgan

- Read a report produced by Shell about an outlook to the voluntary carbon market

[MUSIC: Joshua Redman, “Courage – Asymmetric Aria” on Beyond, Warner Records Inc.]

Coming up – North Atlantic Right whales are getting smaller.

We’ll tell you what scientists think ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joshua Redman, “Courage – Asymmetric Aria” on Beyond, Warner Records Inc.]

Beyond the Headlines

The first electric turbines at the Hoover Dam went into service on October 26, 1936. (Photo: James Watt, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

And it's time for a trip now Beyond the Headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi Bobby, if you're a farmer, or if you're in the big ag sector, you're already thinking about the 2022 growing season. And there's growing concern that an herbicide shortage for 2022, according to researchers from Purdue University. Glyphosate is a part of the subject. There's a big glyphosate production plant in Louisiana that was damaged by Hurricane Ida. There are shortages in workers on the docks and truckers throughout the country that affect the supply chain. The same supply chain issues, we hear about just about everything, are going to affect herbicides, and therefore affect what's available to eat next year.

BASCOMB: Yeah, the supply chain problem it really hits so many different facets of our economy and lives. From what I've read too a lot of the glyphosate, these herbicides are manufactured in China, which is a real bottleneck for manufacturing and getting things out to the world.

DYKSTRA: Right. The key components are manufactured elsewhere, including China, that's a part of that big global supply chain that's about to turn around and bite us in a big way. If it's not already. We hear a lot of talk on the news about Christmas season and Christmas gifts being affected. After that comes the farming and food season throughout the country, and the way farming is set up these days, there's so much reliance on herbicides like glyphosate. Many people know it as Roundup. That's also under a lot of pressure right now from lawsuits, primarily, from farm workers and others who think that they've been damaged by exposure to glyphosate.

BASCOMB: Alright, well, what else do you have for us this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Here's a good idea. There are some if's attached to it, and we'll get into the if's. But how about growing some crops under solar panels. In Colorado, Wired Magazine, visited a small farm, 24 acres, they grow things like beets, and tomatoes, and they grow them on four of those acres under solar panels. So not only are you providing food, but you're generating a source of sellable electricity, and the two actually can work pretty well in tandem.

One farm in Colorado is growing plants under solar panels. (Photo: Maryland GovPics, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, that sounds like a great idea. But don't those plants need a lot of sun to grow well?

DYKSTRA: Many plants can grow well with the sun that comes through the solar panels. Not only that, but a lot of plants need sun, but they also, in most cases, need some shade. So, the solar panels can protect that, and when those plants are shadier and cooler, they, in some cases, need a lot less water to thrive and the solar panels, providing shade can help with that as well.

BASCOMB: Well, it sounds like a win-win. I mean, you have healthier plants, save water, generate income for the farmers, who you know, maybe selling electricity or at least saving on their own electricity bill and generating renewable energy. It sounds like a great idea.

DYKSTRA: It's a win-win, if there's enough money for farmers to make that heavy front ends investment in the solar panels.

BASCOMB: Well, that's certainly true. And what do you have for us from the history books this week.

DYKSTRA: October 26, 1936, the first electric turbines at the Hoover Dam and the Colorado River goes into service. That massive dam, not far from Las Vegas, provides not only water for drinking, water for crops, but hydro power in much of the southwestern US. And of course, California and Arizona are the sources of many of the crops grown and consumed in the US.

BASCOMB: Well, hydropower, though it has its limitations. I mean, it does wreak havoc on the rivers upstream. And of course, now you know, the Lake Mead behind the Hoover Dam is at its lowest level since the dam was created. That can't be very good for generating hydroelectric power.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, it's also a problem at the Glen Canyon Dam upstream in the Colorado on near Lake Powell, another big artificial lake. But think back to 1936. No one could have imagined that there'd be upwards of 40 million people in Southern California, Arizona, Southern Nevada. And one of my favorite markers for this, 1936, there were six National Hockey League teams in North America. Now there are four in the desert, in Phoenix and Las Vegas. Who to think in 1936 that was completely out of our minds. As is the huge population growth that not only has happened but is projected to continue even though the region is running out of water.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I'm sure the engineers who developed the Hoover Dam never could have imagined, you know, millions of people living in the desert and of course, climate change, which is making the you know, making the hydrology a lot more challenging.

DYKSTRA: Right, and living in the desert also means you've become reliant on electricity, which for all intents and purposes also didn't exist in 1936, in the form of air conditioning.

BASCOMB: All right, well thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Learn more about the herbicide shortage

- EHN | “As masses of plaintiffs pursue Roundup cancer compensation, migrant farmworkers are left out”

- Learn more about growing crops under solar panels

- Learn more about the Hoover Dam

[MUSIC: Jamestown Revival “Young Man”, Single, Jamestown Revival Recordings marketed and distributed by Thirty Tigers]

Right Whales Struggle to Grow

A mother North Atlantic right whale and her calf (Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

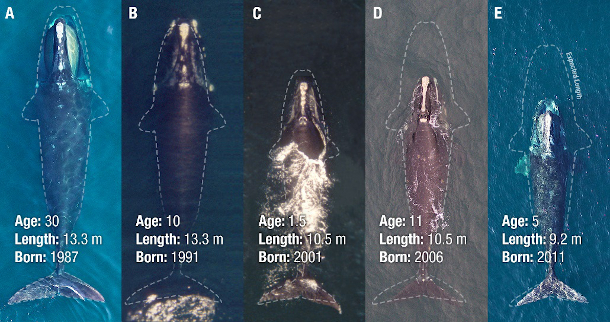

BASCOMB: A US District court recently blocked a federal ban on lobstering in a section of the Gulf of Maine that was designed to safeguard endangered North Atlantic Right whales. Judge Lance Walker ruled federal regulators had relied on “markedly thin” analysis and had failed to provide hard enough evidence that the Right whales too often get entangled in fishing gear, encounters that scientists say can be fatal. The government is expected to appeal the ruling as it continues to try to protect North Atlantic Right Whales, which are one of the most endangered cetaceans in the world, with roughly 400 remaining. This year scientists say 19 living Northern Right Whale calves were born, which is more than the past 3 years combined but still less than a third the previous average annual birth rate. Climate change, vessel strikes, and the entanglements cited in the court case have had scientists sounding the alarm about this crashing population for decades. And now researchers have discovered yet another threat to their survival. The whales, on average, are actually shrinking in size. Typically, they should be roughly 140,000 pounds and up to 52 feet long. But a new study finds that young North Atlantic Right whales are not growing to their full potential. For details, I’m joined now by Amy Knowlton, a Senior Scientist at the New England Aquarium and a co-author of the study. Welcome to Living on Earth, Amy!

KNOWLTON: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

BASCOMB: So, you are a co-author on the study that found that Right whales aren't growing as large as they used to, what's going on there? What have you found?

KNOWLTON: Well, what we found is that the average reduction length is about three feet when they reach their full length. So, three feet shorter than they were back in the early decades of our studies in the '80s, and '90s. So that's a pretty dramatic reduction in size. A few things seem to be going on. The main concern we have is that there's some indication that entanglements are leading to these shorter whales. The entanglement part of that story was the strongest signal when everything else was compared. And that was only a subset of whales that met the criteria to be included in this paper, meaning that it was either young whales under 10 years old that had attached gear, or it was calves whose mother had either attached gear or severe injuries when that calf was nursing.

BASCOMB: So, what is the source of the entanglements? It's, it must be fishing gear, obviously. But what's going on there exactly?

A few examples of stunted growth in North Atlantic right whales, compared to their expected length given their age. (Image: New England Aquarium)

KNOWLTON: Well, there's a lot of lobster gear, crab gear and gill net gear, especially up here off the coast of New England. Right whales, also their filter feeders, so they are moving through the water with their mouths open. And that's where these entanglements begin, typically, is in the mouth. So, they'll hit that rope, they'll start flailing because they're all freaked out, because they're hit something foreign to them, and then they get all wrapped up. If they can't break free from the bottom gear, they could drown. But the other scenario is that they can break free eventually, but they're then trailing a lot of rope behind them, causing energetic impacts, and also probably affecting their ability to feed well. We've shown that over 85% of the population has endured at least one entanglement and close to 60% of the population has endured two or more entanglements.

BASCOMB: So, they're literally swimming through the water with all of this gear attached to them. It's very heavy, I can understand how it would be a real drain on their energy stores. To what extent are smaller whales less resilient over time? Or how is it affecting their ability to survive?

KNOWLTON: Well, the concern is that because they're smaller, they're not going to have as healthy of blubber reserves that a larger whale might have. And so, they would be less resilient to the impacts of climate change, for example. Also, if it's a reproductive female, we know that reproductive females use a lot of their blubber to support, a nursing calf. They nurse the calf for about at least a year. They're already in diminished blubber capacity, and then they lose that blubber through giving birth and lactating, then they are probably going to take longer to recover, to be able to build up the reserves to have another calf. We've probably lost some ability for these females to sort of be really productive females in the species in this population. It's a concern that needs to be considered as we try and keep the species from going extinct. There are certainly stressors that we can't address, such as food limitation and climate change. But the Right whales are dealing with that. We know that Right whales are pretty resilient and adaptable. And we've seen them adapting to changing food resources in recent years. But the entanglement threat and the vessel strikes that occur in the species are things that we could control much better than we've been doing.

A group of male North Atlantic right whales surfacing between feeding dives off the coast of southern New England in October 2021. (Photo: New England Aquarium)

BASCOMB: That must be frustrating for you, as a biologist, to watch them adapt to one stressor that we've introduced, you know, the shifting habitats, if it's becoming too warm for them, in some places, they have to move north to find a more suitable habitat and the food that they need. But when they move north, they find all of this fishing gear that's entangling them and causing a whole new problem.

KNOWLTON: Yeah, it is a very frustrating situation to see. I mean, it's the entanglement threat has been there for decades. And it's certainly been exacerbated, partly because of climate change. But also, ropes have become much stronger in recent decades. Ideally, ropeless fishing gear would be the ultimate solution to this. And there's been a tremendous amount of progress on that front.

BASCOMB: How exactly would ropeless fishing gear work?

KNOWLTON: There's a few different designs being considered. But the general idea is to stow the end line and the buoy at the sea floor. When the vessel comes by and sends out an acoustic signal to that device on the sea floor, it releases that rope and buoy to the surface.

A North Atlantic right whale named Cassiopeia photographed in October 2021. (Photo: New England Aquarium)

BASCOMB: How is that potential change being received by local fishermen? I would think you need buy in from them to implement some of these changes.

KNOWLTON: Yeah, I think there's definitely some concern about from fishermen about the cost. But I think that's hopefully if the more broadly, it's used, the costs will come down. And there's concern about whether it can be used effectively. But there again, there's been a lot of testing with various fishermen. You know, I think some fishermen are definitely willing to engage and to test the gear and try and make it work. And, you know, fishermen don't want to see whales die in their gear. You have to work with them to sort of figure out the quirks and sort out the changes that would improve that gear. And that's been what's been happening the past few years, and it's really encouraging to see that. Ideally what we've suggested at the aquarium is that you first phase it in high use areas where Right whales are known to aggregate or offshore waters where we know the gear is more risk to Right whales and then start phasing it in more broadly after that, because it's a big shift from how they fish now.

BASCOMB: So Amy, what can the average person listening right now do to help the Right whales?

Amy Knowlton is a Senior Scientist in the Kraus Marine Mammal Conservation Project at the New England Aquarium. (Photo: Courtesy of the New England Aquarium)

KNOWLTON: Well, there's a couple of things that people could do. First, if you're out on the water here on the east coast, and you happen to see a Right Whale, please report it to either the Coast Guard or to NOAA Fisheries. Or you can get an app for your phone called Whale Alert, and you can report sightings and photographs that way. You should remember that you're not allowed to approach Right whales closer than 500 yards, but you can still collect photographs and determine species from that distance. So please report sightings and operate carefully in the waters if you're out operating your vessel on the east coast. Make sure you are just very vigilant and keep your speeds as slow as you can and try and be careful there. And then if you're out eating seafood at a restaurant, perhaps ask where your seafood is coming from, whether it's been fished with whale-safe or whale-friendly gear. They might not know immediately, but at least they'll recognize that they need to pay attention to what their visitors are asking them to investigate. Those are a few things that people can really do to help support Right whales.

BASCOMB: Amy Knowlton is a senior scientist in the Right whale Research Program at the New England Aquarium. Amy, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

KNOWLTON: Yep. Thank you.

Related links:

- Find the study in Current Biology

- Learn more about North Atlantic right whales

- Find the Whale Alert app

- About Amy Knowlton

[MUSIC: Jeskost “Whales”, Single, Johnson Studios]

King Penguins Entering Surf

A colony of King penguins gathers on the rocks on South Georgia Island. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: We stay at sea now but much further south off Antarctica with our explorer in residence, Mark Seth Lender.

King Penguins Entering Surf

Salisbury Plain, South Georgia Island

© 2021 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

They gather, forming up before a single-entry point. They pause, then plunge in single file crossing the surf line into the sea. Bodies crash, flippers collide, the salt spray luminous in the gray of afternoon rain. In such King Penguin seeks to hide; protection, in turbulence and a multiplicity of forms.

For the sea is a toothy place. A place of hunger that lurks unseen. Of foaming mouths. And jaws that bite. And luck is all that stands between.

Bright are the orange markings that crown the Penguin King, that cup his hidden ears; the yellow that trails like the silken cord of rank and station down along his neck; the night-blacked face and the Osage orange of the eyes; cadmium yellow plated like a badge of armor on his breast; an Aurora of Blue the talisman about the throat; and none of this protects him.

Through the waves he leads that leave to feed, their Hope in the Southern Ocean.

Heading out, they cross the paths of those now full and fed whose Hope is now the Land. These returning quickly parallel the waves as they near the shore, that lurking leopard seal and fur seal furious with hunger will be confined in their takings.

King penguins splash into the surf on the shore. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

In numbers they survive.

Meeting the slope of the beach King Penguins break free. They stand upright and shuffle towards the open shelter of the shore, water shedding down their robes of feathers. One raises up his head and cries:

I am alive! I am still alive!

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Find the corresponding field note for this commentary

- Learn more about author and photographer Mark Seth Lender’s work

- Special thanks to Destination Wildlife

[MUSIC: Trampled By Turtles, “Beautiful” on “Stars and Satelites”, Banjo Dad Records]

ANNOUNCER: Funding support comes from, Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

C’waam And Koptu: The Fish at the Center of the Klamath Basin’s Water Crisis

C’waam, also known as Lost River suckers congregating to spawn on Sucker Springs in Upper Klamath Lake, Oregon. (Photo: Brian Hayes, USGS-Klamath Falls Field Station, public domain)

BASCOMB: In the drought-stricken Klamath Basin along the California-Oregon border, water is a precious resource. Who gets that water hinges, in large part, on two endemic species of fish that make their home on the Klamath and nowhere else in the world. Jefferson Public Radio reporter Erik Neumann has the story.

[BOAT SOUNDS]

NEUMANN: Biologist Alex Gonyaw aims his Boston Whaler up the eastern shore of Upper Klamath Lake. He’s showing off what, he says, used to be abundant habitat for juvenile fish.

GONYAW: It’s a mosaic of cattails and willows and tulles, or bullrushes.

NEUMANN: At almost 30 miles long, Upper Klamath Lake is the home to several types of fish that only live here.

GONYAW: So, the more hiding places for juvenile creatures the better they generally tend to do.

NEUMANN: Two of them are called C’waam and Koptu in the traditional Klamath language or in English the Lost River and shortnose sucker. They have a stubby face and wide lips and can live to be 50 years old.

GONYAW: They’re an endemic species. It's only found here, nowhere else in the universe and due to their sort of near extinction level status, they are becoming something of a figurehead in the water crisis here.

NEUMANN: In recent years, the juvenile fish have been dying, causing the overall population to crash. Five years ago, when Gonyaw started working for the tribes, there were about 20,000 shortnose suckers in the lake. Estimates today are just 3,400. The Lost River sucker is disappearing at a similar rate. Exactly why these fish are dying is unclear, but biologists believe it’s because of poor water quality and habitat loss that’s impacted by low water in the lake. Those factors make their future grim.

GONYAW: There's a catastrophic event likely in the next few years.

NEUMANN: In this extremely dry year in the Klamath Basin, much of the debate over who gets water depends on these fish. Water flowing out of the lake has been shut off to farmers who rely on the federally managed irrigation system. Even further down the Klamath River, threatened salmon are also getting the bare minimum. Besides being protected under the Endangered Species Act, the C’waam and Koptu are culturally important to the Klamath Tribes who say they’ve subsisted on them since time immemorial. At a recent rally in Klamath Falls, Tribal Chairman Don Gentry talked about how the Klamath people prayed for the fish to return after hard winters.

GENTRY: Those fish are so important. We wouldn’t be here likely without those fish that helped us survive.

NEUMANN: The declining fish numbers also illustrate a problem with the US government’s treaty. In 1864 the Klamath Tribes gave up around 20 million acres of land, in exchange for the right to hunt and fish. Gentry says those treaty rights don’t mean much if there are no fish to catch.

Klamath Tribes Senior Fish Biologist Alex Gonyaw boats across Upper Klamath Lake. Gonyaw is working to try to save the endangered C'waam and Koptu, or Lost River and shortnose suckers that live in the lake. (Photo: Erik Neumann / JPR)

GENTRY: What good is a treaty if you don't have the resources?

NEUMANN: He says the Endangered Species Act is meant to prevent species from going extinct. It doesn’t live up to the treaty responsibility of providing harvestable resources.

GENTRY: So we’re basically relegated to the ESA. And that’s.. that’s very minimal…It's not even working, you know, for us. But that's the thing that we have.

NEUMANN: The Klamath Tribes have senior water rights. But farmers in the basin are the other group that is linked to these fish. Mark Johnson represents irrigators with the group Klamath Water Users Association.

JOHNSON: Ultimately the farmers they want as they want all fish species to thrive is if the fish are doing well, everybody's doing well.

NEUMANN: For 15 years Johnson studied Lost River and shortnose suckers as a fish biologist with the US Geological Survey. One of the big frustrations from the irrigator standpoint, he says, is that water is prioritized to protect fish, but they’re still dying. But taking more water out of the lake would be gambling with the existence of a species.

JOHNSON: Yeah, I mean you are. But in terms of an extinction level event, I don't think that's actually going to happen. But on that trajectory we’re on right now, basically managing the lake the same way we have for over 20 years we haven't moved the needle. So, something has to change.

NEUMANN: There are no long-term solutions for saving the native fish populations. For the first time this year the Klamath Tribes are raising juvenile fish from eggs in a hatchery. When mature, they’ll be released in Upper Klamath Lake. This exceptionally dry year is shining a spotlight on the Klamath Basin and how there just isn’t enough water to go around. And with current climate trends, there’s little reason to think abundant water will be available any time soon.

Erik Neumann, JPR News.

BASCOMB: Reporter Erik Neumann’s story comes to us courtesy of Jefferson Public Radio.

Related links:

- Find this story and more coverage of the Klamath water crisis on the JPR website

- Watch a Klamath Tribes video about the fight to save their sacred C’waam and Koptu fish

- About Reporter Erik Neumann

[MUSIC: Trampled By Turtles, “New Son/Burnt Iron” on Palomino, Banjo Dad Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A woman from Uganda is striving to bring a youthful African voice to the international climate talks. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Sonny Rollins, “St.Thomas” on Saxophone Colossus, by Sonny Rollins (based on trad. Bahamian "Sponger Money"[1] and trad. English "The Lincolnshire Poacher"), Fantasy]

A New African Voice on Climate

Vanessa Nakate’s book A Bigger Picture: My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis recounts her journey as an environmental justice activist and serves as a roadmap for empowerment to those who want to follow her lead and act on the global climate crisis. (Photo: Courtesy of Vanessa Nakate)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Three years ago, at the age of 15 Greta Thunberg started the Fridays For the Future climate strikes by sitting in front of the Swedish Parliament, and millions of people around the world ultimately joined her cause. One of them was Vanessa Nakate of Kampala, Uganda who was just getting out of college at the time. Teenaged girls in Uganda don’t typically have the same social freedoms as many in the Global North have to be out on their own picketing and demonstrating. But at age 22 Vanessa Nakate could, as college age women have a lot more freedoms in her culture. And in the face of climate change, intensified floods and droughts that ravaged Uganda at the time Vanessa was inspired by Greta to organize and start holding climate strike signs herself in front of the Ugandan Parliament. Greta Thunberg soon heard of Vanessa through social media and in January of 2020 Vanessa was invited to join Greta for a press conference at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. But the Associated Press cropped Vanessa, the only black woman, out of a widely circulated photo that included Greta Thunberg and three other white European activists. Comments citing that editorial decision as racist soon went viral. And since that incident Vanessa has used her visibility to bring light to climate struggles in the Global South. In her book, A Bigger Picture: My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis, Vanessa points to how climate change is impacting Africa and the short shrift that she and other people and nations of color receive at the UN climate talks. Vanessa Nakate welcome to Living on Earth!

NAKATE: Thank you so much happy to be here.

CURWOOD: You know, in the US we've had fires in the west of floods throughout the Midwest storms and droughts, but what kind of climate change effects are going on in Uganda?

NAKATE: The climate crisis is a present reality in Uganda. With the rising global temperatures, weather patterns are changing and we are seeing more extreme weather events. Uganda as a country heavily depends on agriculture for survival for many communities, especially those in the rural areas. But with the rising global temperatures many people are threatened with floods, droughts and landslides, causing massive destruction, massive loss of lives, loss of homes, farms and businesses. In the eastern part of the country, in areas around mountain Elgon, areas of Bududa and Bundibugyo people have experienced torrential rainfall causing massive flooding and landslides in the western part of the country in areas of Kasese, because of the rising global temperatures, many people have been displaced and still are living in camps because of extreme flooding.

CURWOOD: Please tell me a story of a particular recent climate related incident that was well not great for people in Uganda.

NAKATE: There are actually a number of events that have happened, but I can talk about one that happened last year. During the pandemic in 2020. The water levels of Lake Victoria rose as a result of extreme rainfall. And many people were displaced from their homes at a time when they had to stay at home to keep themselves safe. And with the rise in the water levels. Not only were farms destroyed, but even toilets were submerged, causing contamination of water sources and threatening the livelihoods of very many people.

Vanessa Nakate stands at center-right and carries a sign saying, "We cannot eat coal... we cannot drink oil."

CURWOOD: Now, you join Friday's for the Future in your 20s Vanessa. And that movement was made up of well, mostly teenagers and younger folks, why did you choose to join? Why did you choose to join the kids?

NAKATE: Yes. When I joined Friday’s for Future, I had also seen the movement and also how the media was reporting about the movement, and being a movement of teenagers and led by teenagers. And also, this is a challenge for some of my friends, because most of them were just finished in college and in their 20s. So, we all had this feeling that this movement was a movement for teenagers. But to me, that wasn't the issue. The issue was talking about what was happening in my country. So, I didn't really pay attention to how the media would report about the movement, whether it's for teenagers or not for teenagers, I just wanted to demand for climate justice and to talk about the challenges that the people in my country were facing because of the climate crisis.

CURWOOD: Vanessa, tell me about some of the projects that you're working on now.

NAKATE: In 2019, I started school project Vash build schools project, and it involves the installation of solar panels and eco friendly cookstoves in schools. And I started this project to help drive a transition to renewable energy in schools in Uganda, and also for the clean cooking stoves to reduce on the firewood that schools were using for preparation of foods. Almost all the schools in my country use firewood for food preparation. But with these eco friendly stoves, the number that is used is greatly cut. So, I hope that with this project, many schools can easily transition to renewable energy at no cost and also receive the eco friendly cookstoves. So far we've done installations in 13 schools.

CURWOOD: You write in your book that when you came actually to the UN, a couple of things happened. Number one, somehow you were asked to leave or move from areas that you didn't see other people being asked to move from. And also, you met with the Ugandan delegation. But when you come home, it was as if that hadn't happened. Can you tell me those stories?

NAKATE: Yes, I remember, one of the people was a part of the Ugandan delegation, sent me an email and asked if I can meet him and talk about my activism. And I did. We met at the UN, I think headquarters, and then after he directed me at the, I think it's like the Uganda house in the United States, New York, and he invited me for breakfast there, and I got to meet a number of the members of parliament, and I remember one of them actually recognizing me and saying that I've seen you on TV, you're the girl who strikes every Friday. And at that moment, I'm like, wait, you've seen me. And you haven't even said anything about the activism that I'm doing, or what are the young people doing, you're just telling me now. And at that moment, there was a couple of business cards, you can reach out to us when you're back in the country. But I remember when I did that, they never responded to my calls. And I had given my number t some of them but they also never called. So I thought that it would be an opening of, you know, me and other youth activists to speak to the parliament, or to speak to members of parliament about the work that we were doing, and about our demands, but it never actually happened. And, yes, the scenario at the UN where I got to be lifted twice from seats, I didn't pay much attention to it when it happened. But later on, while I was writing the book, I reflected back on it, and I started to think about why it had actually happened, and why I had to stand for a while until I finally got a seat. So the experience at the UN Youth Climate Summit was not as expected.

CURWOOD: So let's talk about the media. We're talking because Associated Press was quite rude to you at the session in Davos, they cropped the picture that didn't include you. And since then, of course, media has been knocking on your door, I'm sure you have more press requests than you can possibly handle. How do you think the media is handling the climate emergency?

NAKATE: Yeah, after the photo crop incident, I started to get very many interviews that I can do. And many times I asked to give the interview to another activist who is also doing activism either in Uganda or in another country. And media sometimes is always, you know, specific, we want you we want you or if it's the other person they want, you know, to know if they're eloquent enough, or if they have done interviews before or if they've spoken at events before. So it puts really a challenge on how the media is reporting the stories of the vast number of activists. And I think also another challenge is that media is putting a face or faces on the climate movement. And I find it really dangerous, because in a way, it erases other people's stories. So media has a responsibility to report about the climate crisis, to point about the climate solutions, to report about the science, to report about the activists who are speaking up, especially activists from the most affected areas, it's important to listen to their stories, every activist has a story to tell every story has a solution to give and every solution has a life to change.

CURWOOD: You write in your book, that you were heartbroken after the incident in Davos, and after your first trip to the United Nations. Talk to me about that. And what would mend your heart? What would heal your heart?

NAKATE: Yes, after my trip to New York for the UN Youth Climate Summit, my disappointment really came from, you know, the feeling that when I got the invitation, and when I was told that I would have a speaking role. I worked on my speech. And I was just really happy to talk about the experiences of the people in my country. And then towards the, you know, the trip, I asked, so how long should my speech be? And that's when I'm told that well, you're actually not going to speak but you will just be able to, you know, be like in discussions with other young activists. And at that point, it was really a disappointment before I left and I couldn't tell my family or my friends because they were very excited and you know, looking forward to hearing me talk about what was happening. So I think that was one of the you know, disappointments I had and also not being able to coordinate and meet as many activists as possible. While there was also a challenge. And then my other disappointment, the one in Davos, of course, I was really heartbroken and frustrated when I saw the picture and also read the article because I remember the press conference, one of the things that I really emphasized was the amplifying of voices from different parts of the world, because the activists from different parts of the world, and it was important for the media to do that. I remember mentioning that while at the press conference, so when I saw, you know, the picture, and then the article, I felt like everything that I said at the press conference, like it didn't matter at all effort, like it just went into the air and immediately disappeared, and no one was really paying attention. So it was really heartbreaking to see the picture. And what would really heal my heart? Yeah, I can say that my heart has healed and I forgive all of them.

CURWOOD: I've wondered myself, I've been to a number of the UN Climate meetings and such. And one thing, I noticed that only white countries, with exception of Japan were included in annex one back in the Kyoto process. And that typically, leadership all seems to be from the global north, there. Yes, there are people of color who sit on committees, and even the General Assembly is chaired by sometimes by persons of color, but the power remains at the Security Council. How effective do you think the United Nations is in dealing with the danger and concerns from climate for the global south, in terms that are strong enough and meaningful enough?

NAKATE: Well, I think that the UN, but not just the UN and the leaders and governments, I think that they're all not doing enough when it comes to handling the issues of the climate crisis in the global south. Because if they were, then we wouldn't be seeing that escalation or the frequent climate disasters in our communities. We wouldn't be seeing this floods or hurricanes or cyclones, or droughts unfolding in our communities. And it's really a responsibility of all these leaders to ensure that the people from the most affected communities are prioritized, and that their stories are listened to, and the solutions are given and, and that climate finance is given for these communities, especially for loss and damage. So it feels like we are still speeding in the wrong direction. And while we do that many people and many communities continue to suffer as a result of climate disasters.

CURWOOD: But we're still in the climate emergency. So before you go, Vanessa,

NAKATE: Yeah.

CURWOOD: We are now, the world, is listening to you. The world is gonna want to read your book, a bigger picture. And you are one among many activists, but like Greta Thunberg, you are now very much noticed as an activist, and from the part of the world that hasn't had much of a voice of activism. What's the message that you want people to know?

NAKATE: My message is really a long message, but I will try to, to put it in, you know, very few words. I come from Uganda, and it's a country in Africa. And it's important for people to know that, historically, Africa is responsible for only 3% of global emissions. And yet Africans are already suffering some of the most brutal impacts of the climate crisis. It's also important to know that while Africa, while the global south is on the frontlines of the climate crisis, it is not on the front pages of the world's newspapers. And it's also important to know that there are a number of activists in the African continent in the global south who are speaking up who are demanding for justice from leaders, from governments, from corporations. So what I would want people to know is that the young people in Africa are speaking up, and they're rising up for the people and they're rising up for the planet. And we want climate justice. We want climate action from the leaders and our voices will not be silenced.

CURWOOD: Vanessa Nakate's book is called A Bigger Picture: My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis. Thanks for taking the time with us today.

NAKATE: You're welcome. Thank you so much.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Rise Up Movement Africa

- Follow Vanessa Nakate on Twitter

- Learn more about how climate change provokes food insecurity and displacement in Africa

- Learn more about the campaign to save the Congo Basin rainforest

- Vanessa Nakate’s solar installation project

- Washington Post “Climate Activists Greta Thunberg And Vanessa Nakate Scold Global Leaders For Lack Of Action”

[MUSIC: Abdullah Ibraham, “Chisa” on Cape Town Flowers, ENJA Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Genevieve Santilli, Teresa Shi, Gabriell Urton, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Destination Wildlife. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth