May 25, 2018

Air Date: May 25, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Alaska Acts on Climate

View the page for this story

Temperatures in the polar regions are rising faster than in the rest of the world, and in Alaska the warming is melting permafrost and bringing stronger storms and rising seas that are eroding coastlines. But Alaska faces a dilemma. Ninety percent of state revenues come from fossil fuel yet burning oil and gas adds to global warming. What’s to be done? Lt. Governor Byron Mallott chairs the Climate Action for Alaska Leadership team that is seeking solutions. He spoke with host Steve Curwood. (08:43)

The Most Toxic Town in America

View the page for this story

The EPA listed Kotzebue, Alaska in 2017 as the most industrially polluted community in the US. Millions of pounds of poisonous dust laden with heavy metals is released annually from mining zinc and lead at the nearby Red Dog Mine. Host Steve Curwood spoke with Pamela Miller from Alaska Community Action on Toxics about the impact. (05:52)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week’s trip with Peter Dykstra beyond the headlines leads to the coast of New Jersey where North Carolina fishermen seem to be moving with their catch as fish species head for cooler waters. Then, Peter tells host Steve Curwood about a stalled solar farm in Kentucky and the coal operation linked to the delay. Finally, the pair note the arrival of invasive zebra mussels in the Great Lakes and the retirement of an environmental news legend. (03:51)

No Refuge in Wildlife Refuges

View the page for this story

President Teddy Roosevelt established the first National Wildlife Refuge in 1903, inaugurating a system of protected areas to offer a safe haven for native and migrating species. But the Center for Biological Diversity now reports that roughly half a million pounds of chemical pesticides are sprayed yearly inside some of these protected areas to support commercial agriculture. Attorney Hannah Connor authored the report, No Refuge, and spoke with host Steve Curwood. (07:28)

Copperheads at Shawangunk

/ Marc Seth LenderView the page for this story

The steep blocky edge of Shawangunk Ridge towers like a fortress above a broad plain in southern New York state. The old, eroding rock of “The Gunks” provides plenty of challenges to climbers and also niches to protect small creatures, like copperhead snakes. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender observes three copperheads intertwined on a stone ledge, and marvels at their languid retreat into the rock. (03:23)

Free the Beaches: Desegregating America’s Shoreline

View the page for this story

The US civil rights movement to end racial segregation in the 1960’s may have been most intense the South, but there were battles in the North, including in the State of Connecticut. Just about all of the Long Island Sound beaches in Connecticut were off limits to people of color until Ned Coll came along. In his 2018 book Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline, historian Andrew Kahrl describes Coll’s creative protests to smash the color bar and let all children cool off on hot days at the beach. He spoke with host Steve Curwood. (17:19)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Byron Mallott, Pamela Miller, Hannah Connors, Andrew Kahrl

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Alaska’s government is seeking answers to fast-rising temperatures in the far North, but 90 percent of its revenue comes from global warming petroleum. Native Alaskans are on the front lines.

MALLOTT: Native peoples live along our coasts in the most verdant and productive areas of our state. But we have coastal erosion in the Arctic so fall storms are causing significant damage along our rivers. And so they, or we, are heavily impacted by climate change.

CURWOOD: Also, national wildlife refuges at risk from chemicals.

CONNORS: Nearly half a million pounds of toxic pesticides were being dumped onto US national wildlife refuges for agricultural purposes. These include dicamba, glyphosate, 2-4D and a pesticide known as paraquat dichloride.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Alaska Acts on Climate

Fossil fuel production revenues accounts for about 90% of Alaska’s state budget, and much of the fuel is transported through pipelines such as the Trans Alaska Pipeline, above. (Photo: Arthur T. LaBar, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The human dilemma of climate change is front and center in Alaska. The far North is warming much faster than the rest of the world, melting permafrost and forcing coastal Alaskans to retreat from the sea. Yet nine out of every 10 dollars in state coffers come from the North Slope production of petroleum, which accelerates climate disruption as it’s burned. In an effort to build consensus to address this dilemma, Governor Bill Walker created the Climate Action for Alaska Leadership Team with Lieutenant Governor Byron Mallott as its chair. Mr. Mallott is also a Tlingit clan leader in Southeast Alaska. He joins us now – welcome to Living on Earth!

MALLOTT: Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: Briefly tell us, what are some of the ways that climate change is having an impact on Alaska?

MALLOTT: I spent personally many summers as a commercial fisherman out of my village of Yakutat. It's right on the Gulf of Alaska, but my oldest son is a commercial fisherman now, and he has fished commercially since he was 18 years old and he said to me, "Dad, I am uncomfortable, sometimes even fearful, being on the ocean now because so much has changed." He said the weather has changed. The movement of salmon and halibut that I fish, the timing is different than they used to be, and so our life is changing. We had in the Gulf of Alaska two years ago a very warm discreet body of water that folks called “the blob,” and it caused the cod fish which had been in the Gulf of Alaskan waters forever to essentially lose 70 percent of its biomass and cod fishing in Alaska was substantially decreased. These are indicators of a changing ocean for sure, and so we have coastal issues, we have in our Arctic areas permafrost, which is melting. We have a lot of change taking place.

CURWOOD: So, how does climate change affect indigenous communities in Alaska? Tell me some of the ways.

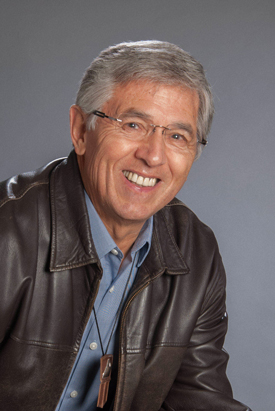

Lt. Governor Byron Mallot is from Yakutat, a small town on the Gulf of Alaska, where commercial fishing is a major industry being impacted by climate change. (Photo: Joseph from Cabin on the Road USA, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

MALLOTT: Right. Native peoples live along our coasts. They live in the most verdant and productive areas of our state, and so they – or we – are heavily impacted by climate change. We have coastal erosion in the Arctic where ice is not shorebound in the way that it used to be, so fall storms are causing significant erosion and damage. Salmon is now becoming much more prevalent in the Arctic part of our state than has been the case in the past. The changes are palpable and they are significant.

CURWOOD: So, the Climate Action for Alaska Leadership Team was established in 2017. Who makes up this team and what are the current policy priorities?

MALLOTT: When the governor and I determined that it was time for Alaska to stand up its own climate change initiative, we believed that all of the residents of Alaska and their institutions, their communities, their leadership needed a voice in this dialogue and in the creation of the policies that will drive our response to climate change, and so the make up of the CAALT as we call it is statewide. It is very broad based. It includes all of the economic and social and leadership and institutional sectors of our state. The governor was particularly anxious that the youth have a voice, so we have two discrete youth members of the CAALT and we want the dialogue and we want the decisions that are made to be the result of a very broad based conversation across our state about the issues of climate change.

Alaska Lieutenant Governor Byron Mallott is a clan leader of the Tlingit Raven Kwaash Kee Kwaan of Yakutat, and his work seeks to build partnerships with Native Pacific peoples for indigenous-focused approaches to climate change. He heads the Climate Action for Alaska Leadership Team. (Photo: courtesy of Byron Mallott)

CURWOOD: Now, it will be a few more months before you are ready with a report from your work with the leadership team but, what's your best guess right now as to some of the responses that are likely to be in that report?

MALLOTT: We will definitely have policy recommendations and action steps identified to strengthen the transition from a fossil fuel-based economy to a renewable energy future. We will focus on emissions in our state. The entire population of our state is roughly three-quarters of a million people, the size of a medium-sized city anywhere else in our country. We have a very small industrial base and so our emissions are but a minuscule fraction of the total. But we will identify how we as communities, as a state, and as individuals can take proactive steps to reduce the emissions. I met, for example, with a group of youth and they inspired me to utter that my next vehicle will be an electric vehicle, it was nothing that I had planned prior to that time, but now I have an obligation and I feel good about it.

CURWOOD: [CHUCKLES] Indeed. Now, the impact on the climate around the world from Alaska is not so much about what you do at home regarding your emissions, but all the oil that you sell into the world market. I believe more than a million barrels a day come out of North Slope, and why do you support opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas exploration that is the even more oil? Surely, some of this position is being at odds with some of the goals you like to achieve with your climate plan.

MALLOTT: Certainly, but we have ... it is likely and this is speculation ... at least a quarter century of continuing to use petroleum at roughly the levels that we do now, followed by a weaning away during that period of time for national security purposes, for meeting market purposes, for revenue purposes for our state, and we think that for many reasons that it makes sense. We also know that we are moving on the North Slope to a future in which the production of natural gas will be as important as oil and the movement of natural gas to market, we are seven days by ship from China, for example, and the opportunity to take gas to market in China will significantly reduce their emissions. So, we think that the opportunities are there, that they are responsible and that we can both move to a future of renewable energy while meeting our fossil fuel energy today.

Alaska Lt. Governor Byron Mallott, on right, joins hands with Governor Bill Walker on their inauguration day, December 1, 2014, in Juneau, Alaska. (Photo: James Brooks, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: By the way, what is the state of renewables in Alaska and how do they figure into your proposal?

MALLOTT: About a quarter of Alaska's energy now comes from renewable resources, wind, hydro. If you remove hydro, which is not considered a renewable resource – at least under federal definition – our renewable resource energy use is roughly 10 percent. We will have goals in our plan that is presented to the governor to continue to increase the development of renewable energy resources. We are a vast land here in Alaska and we have significant opportunity to do so.

CURWOOD: So, your peoples are the oldest on this continent, and what do you think that native peoples can tell the rest of us about how to deal with climate?

MALLOTT: I think that because it is First peoples, indigenous peoples that live in areas that are heavily climate change impacted as we speak, I am advocating and working with a group of Pacific and now Canadian First Nations People to create an indigenous climate change alliance that would allow indigenous people, First Peoples, to create our own voice in the climate change discussion going forward because that is critical both to us and I think that we can bring something meaningful to the rest of the world.

CURWOOD: Byron Mallott is the Lieutenant Governor of Alaska. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, sir.

MALLOTT: Thank you so much.

Related links:

- Climate Action for Alaska

- New York Times: “‘Impossible to Ignore’: Why Alaska Is Crafting a Plan to Fight Climate Change”

[MUSIC: Rokia Traore, “Dounia,” on Tchamanche, Nonesuch Records]

The Most Toxic Town in America

Kivalina is a village on the coast of the Chukchi Sea, where most of the residents are Iñupiat, a native Alaskan people. This is one of the towns most endangered by toxic releases from the Red Dog Mine, but Kivalina is also imperiled by coastal erosion. (Photo: ShoreZone, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Another source of risk in Alaska is mining. The most recent toxic release inventory of the EPA lists Kotzebue, Alaska, as the worst industrially polluted town in the US. Its hundred residents are annually assaulted by more than 750 million pounds of toxics, including lead, cadmium, and mercury. All this contamination comes from the Red Dog mine that produces lead and 10% of the world’s zinc. The impact is even worse for the native Alaskan villages of Kivalina and Noatak, which are much closer to the mine itself. Pamela Miller is Executive Director of Alaska Community Action on Toxins.

MILLER: The primary problem is that due to the huge fugitive dust emissions and releases of toxic chemicals to the streams and rivers downstream from the mine, the lands and waters are contaminated with heavy metals, and these are lands that have been used for generations by the native communities in that region for subsistence. So, the gathering of greens and berries, the gathering of medicinal plants, the hunting of animals such as caribou and fish and beluga, and these are all downstream or downwind from the mine.

CURWOOD: So, what health effects have been observed?

MILLER: Well, there haven't been any detailed health investigations. The difficulty is that these communities are very small, and there has never been a very in-depth health assessment of the public health impacts of this mining operation in that region. There is concern especially in the community closest to the mine about health effects that include kidney disorders and neurological problems.

CURWOOD: So, what's being done to protect the environment and the local people from all this toxic waste?

The Red Dog Mine is the source of most of the toxic pollution near Kotzebue and Kivalina. Opened in 1989, it is the largest producer of zinc worldwide, and is expected to stay open until 2031. (Photo: Robert Cummings, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

MILLER: Well, it used to be that they transported the ore from the mine in open trucks along a 50-mile corridor from the Red Dog Mine to the Chukchi Sea port. Huge amounts of fugitive dust, which included high concentrations of heavy metals were simply blown off the trucks and distributed in a wide swath on either side of the road. They have taken measures to control those fugitive dust emissions and that is probably the primary protective thing that they've done.

CURWOOD: What about all the riverways, the streams that are getting contaminated with wastewater from the mining operation? What plans are there to protect the waterways?

MILLER: Well, they have controlled some of their releases through the creation of storage ponds and tailings, but these simply slow down the releases further downstream, I think, and while they – the tailings ponds in these storage facilities will temporarily curtail the flow of contaminants downstream and downwind, this is a problem that will persist for many generations to come because I don't believe the corporation will be held accountable for responsible cleanup of this site. It's a Superfund site in the making.

CURWOOD: So, what's the economic balance of this Red Dog Mine? Some people would say, well, it creates jobs. Other people say it's destroying jobs. What's your perspective?

MILLER: This mine actually provides very few jobs to local people, and I think the economic benefits are way overblown, and I think much of the revenue that is generated from the mining of heavy metals from the Red Dog Mine actually benefit a foreign corporation that's based in Canada, and I don't see that the local communities benefit very directly whatsoever.

CURWOOD: So, what about cleaning up these areas? I mean what what's the state doing about this? What's the Environmental Protection Agency saying about the situation?

MILLER: Well, this is a site that's very remote, and so the regulatory agencies, whether state or federal, really cannot do any inspection or regulatory activities without informing the mine that they're coming. It's so remote and I think to a large extent there is no regulation of this facility.

Pamela Miller is the Executive Director and founder of Alaska Community Action on Toxics. (Photo: Alaska Community Action on Toxics)

CURWOOD: From your perspective then, Pamela Miller, what do you see as the ideal future of this Red Dog Mine?

MILLER: Well, I think the corporation that has operated this mine now for more than 20 years really needs to be held accountable for the containment and control of the contamination that they've produced and to make sure that this site is cleaned up so it doesn't cause further public health harms from this mine site that they've created.

CURWOOD: How long have you been working on this project, and what gives you hope that something can be done for the people as well as the wildlife and the environment there to least mitigate these large toxic effects from the Red Dog Mine?

MILLER: We've been working on this since at least 2004 when we produced an investigative report about the contamination from the Red Dog Mine. We've pursued litigation to control contamination through the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act, so we have effectively reduced the fugitive dust emissions and the releases to the surface waters. What really needs to happen over the long-term is that the agencies need to make sure that when this mine shuts down that the corporation does not leave the land in a contaminated state so we don't have contamination in perpetuity.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you for taking the time with us today. Pamela Miller directs the Alaska Community Action on Toxics. She’s based in Anchorage. Again, thanks so much for taking the time.

MILLER: You're welcome.

Related links:

- Listen to our coverage of Kivalina’s lawsuit against ExxonMobil

- Learn more about the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory

- Alaska Community Action on Toxics

[MUSIC: David Bowie “Plan” on The Next Day 2013 Columbia Records]

CURWOOD: Fear of snakes – and fear of falling – are just ahead here on Living on Earth, keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: BJ Leiderman, featuring Bela Fleck, “Bela BJ 1” on BJ, www.bjleiderman.com]

Beyond the Headlines

Summer Flounder, one of the species that’s moving north because of warming ocean waters due to climate change. (Photo: FWC Fish and Wildlife Research, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Let’s check in with Peter Dykstra now – Peter’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org down there in Atlanta, Georgia. Tell us, what’s going on beyond the headlines?

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. Greetings from the South where the news is that seafood is moving north, at least in this hemisphere, as a result of warming waters. We’ve heard that lobsters are beginning to vacate Long Island Sound and the shores of Southern New England – it’s having an impact on the industry there. Similar news from Alaska where salmon are not being found in some of the places where they’re traditionally fished.

But here’s one from the East Coast that could result in some serious conflict: there are fish pursued by both commercial and sport fisherman like black sea bass and summer flounder (also known as fluke) that are beginning to vanish and move North from places like North Carolina. North Carolina fisherman, in turn, are showing up off New Jersey where they’re still plentiful (there’s potential for conflict with Jersey fisherman) and those North Carolina fisherman are burning more fuel just to get to their catch.

CURWOOD: Yeah, you know, I don’t think I’d want to mess with a New Jersey fisherman trying to muscle in on his or her territory. Hey, what else do you have for us?

The bright red tint to this runoff from a mountaintop removal reclamation site in Magoffin County, Kentucky indicates the presence of iron and other minerals. (Photo: ilovemountans.org, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well here’s one that’s a little complicated. The largest solar farm in the state of Kentucky’s history is being stalled by a cleanup, that’s also stalled, of a Mountaintop removal site in Appalachia.

CURWOOD: I can understand that – mountaintop removal is like strip-mining on steroids. They just come in and blow everything up, it makes a heck of a mess. It could take years to clean that up.

DYKSTRA: And when it’s cleaned up it’s not necessary clean and it’s nothing like the previous mountain ecosystem that was there. The site is owned by Kentucky fuel – that’s run by the family of Jim Justice, the governor of the neighboring state of West Virginia. They’ve taken the state of Kentucky to court over the cleanup, saying in order to clean up this site and enable a solar farm to be built next to it, they will have to go dig more coal to make more money to do the cleanup.

CURWOOD: Kentucky fuel … I thought it was Kentucky fried chicken!

DYKSTRA: Kentucky fried climate?

A cluster of zebra mussels consumes a boat propeller. (Photo: Government of Alberta, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Oh yeah I guess maybe that’s what’s happening. Alright let’s look in the history vaults now what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Let’s go back to June first, 1988 – also exactly 30 years ago. Zebra mussels were found for the first time in the Great Lakes system. Specifically in Lake St. Claire –that’s the smaller lake between Lake Huron and Lake Erie near the cities of Detroit Michigan, and Windsor, Ontario.

CURWOOD: And Zebra mussels, I mean, they may be tiny but they’re a big problem if like you have a water supply for a city or you have a factory or a power plant. They clog up the intake pipes of those things and they go everywhere.

DYKSTRA: Right, Zebra mussels are native to the Caspian Sea. They of course hitched a ride over here on the hulls of freighters and other ships. They’re a major nuisance species and potentially could affect other areas – not just the great lakes.

CURWOOD: Yeah, they don’t have a natural predator in the Great Lakes.

Hey Peter, before you go, you’ve heard the news about our friend Rocky Barker … he’s retiring!

DYKSTRA: He’s retiring! Rocky is almost a legend among environmental reporters. He’s based in Boise, writes for the Idaho Statesmen. He’s been doing this for a quarter century, been writing in general for longer than that and he leaves behind a huge legacy of reporting on the environment.

CURWOOD: He certainly will be missed but you know, he’s so funny I think we’re still going to be hearing from him.

Embed:

DYKSTRA: Right, well one of his biggest contributions was to follow up on the recovery of Yellowstone National Park after their catastrophic fire that was also 30 years ago. He wrote a book about the recovery and he had a slide show that he toured around with which he of course called, “the Rocky Barker Picture Show.”

CURWOOD: Indeed. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Thanks Peter, we’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay Steve thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, Loe.org.

Related links:

- The Philadelphia Inquirer: “N.J. flounder, sea bass pushed north because of climate change, say scientists”

- InsideClimate News: “Solar Plans for a Mined Kentucky Mountaintop Could Hinge on More Coal Mining”

- NYTimes: “Zebra Mussels Emerge As a Growing Threat”

- Idaho Statesman: “Rocky Barker prepares to retire with an emotional walk through his past, future”

[MUSIC: Time Warp from Rocky Horror Picture Show https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tkplPbd2f60]

No Refuge in Wildlife Refuges

Five green heron chicks perched on a tree at Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge in Alabama. (Photo: Roy W. Lowe / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

CURWOOD: Summer can be an excellent time to get outside and visit the vast American network of parks, monuments and wildlife refuges. The national parks and monuments often offer amenities from lodging and restaurants to guided tours and friendly docents, while the national wildlife refuges tend to be simpler affairs, with basic trails and waterways. And there are a lot of them: some 562 national wildlife refuges cover more than 150 million acres across the country, with some areas completely off limits to humans and other zones open for hunting and fishing.

A number of national wildlife refuges also allow commercial agriculture. And according to a study by the Center for Biological Diversity, migrating birds and other wildlife in those refuges are at risk from the yearly spraying of a half million pounds of pesticides. The Center’s Senior Attorney Hannah Connor wrote the report and joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth Hannah!

CONNOR: Thank you, Steve. Pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: If you could please tell me a bit about the National Wildlife Refuge System, why was it created and what's its purpose today?

CONNOR: So, the National Wildlife Refuge System itself was established in 1903 by President Teddy Roosevelt. So, it was initially established for a wildlife refuge in Florida and it was established because there was so much hunting going on that birds were … the populations were declining from plumage in particular. And so he established them to be able to protect all these birds and protect their future, and that has grown since then to over 560 national wildlife refuges that are established to protect species and migratory birds and to provide a safe refuge for wildlife.

CURWOOD: Now, you write in your report that a number of refuges actually allow commercial agriculture within the protected areas. Why and how many?

CONNOR: Agriculture is allowed on national wildlife refuges to provide forage and to provide habitat for species and often for birds. And agriculture can do that so they can grow things like corn and soy, things like sorgum, and those crops come along with a lot of pesticide use. Nearly half a million pounds of toxic pesticides were being dumped onto U.S. national wildlife refuges for agricultural purposes and every region except for region 7, which is Alaska, allows for it.

CURWOOD: Tell me a bit about the specific chemicals that are often used in the scale of their use on the national wildlife refuges?

CONNOR: These pesticides include some very problematic and really well known pesticides including dicamba, glyphosate, 2,4-D, and a pesticide known as paraquar dichloride. We saw that in 2016 more than 116,000 pounds of glphosate were applied to agricultural lands and national wildlife refuges, and glyphosate is incredibly well known and its harmful to monarch butterflies, something that is particularly problematic. It kills milkweed which monarchs depend on for their lives. It has caused such a problem in this swath of the midwest where monarchs live and where they migrate, the monarch populations have been plummeting, and 2,4-D which we saw applied in almost 16,000 pounds in 2016 on national wildlife refuges, that is volatile, it's highly prone to drift and it can impact non-target plants and reduce available resources for pollinators. It can impact freshwater fish. It's been known for exposures to amphibeans and all sorts of other wildlife that rely on these wildlife refuges.

CURWOOD: So, a migrating bird drops into one of these refuges, it's been sprayed, she gets a diet of toxic insects and pecking in the soil, toxic soil and having a drink of water – toxic water.

CONNOR: Exactly.

CURWOOD: Please tell me about a specific wildlife refuge where the use of pesticides is really a concern.

CONNOR: So, one of the wildlife refuges that we looked at is called the Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge complex, and it is in Alabama, and the Wheeler complex is composed of the Wheeler, Key Cave, Fern Valley, Sauta Cave, Watercress Darter and Caba River National Wildlife Refuges, and they use a significant amount of pesticides on both the Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge and Key Cave. Not only is this refuge important, incredibly important, for migratory birds, but Key Cave itself was a refuge that was founded for the purpose of preservation of a species called the Alabama cave fish. The only place the Alabama cave fish is known to exist is in underground pools in the Key Cave National Wildlife Refuge.

CURWOOD: If you say this wildlife refuge in Alabama has a fair amount of chemical usage, there are a lot of migrating birds that make that long journey across the Gulf of Mexico and are looking to touch down in – in Alabama.

CONNOR: There absolutely are, and for Wheeler, for example, it's actually well known as being a touchdown point for Whooping cranes, in particular, and because there has been so much development and so much loss of habitat within that corridor, it has become increasingly important to their migration and to their ability to get from point A to Point B. And if they can't hopefully use the Wheeler National Refuge, not only does the refuge lose its purpose, but it also can severely affect their health and their ability to take refuge and take a break from their flight patterns and to continue on.

CURWOOD: So, I'm just scratching my head here a bit because if wildlife refuges are meant to be a refuge for wildlife and spraying these chemicals, these pesticides inside them inherently kills wildlife, how is this even legal?

CONNOR: I think that's a fantastic question and I, too, am scratching my head about this. Universally we've seen that people are shocked with these facts and one of the reasons that it is so shocking is that especially combined with the missing of the refuge system which is for the conservation and protection of wildlife, the cause for concern is just so obvious.

Hannah Connor is a senior attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity. (Photo: Hannah Connor)

CURWOOD: Back in 1903 I guess these refuges made sense for agriculture. If somebody was growing corn, the stuff that didn't make it into the bin at harvest the birds would pick over, it would be a place to eat but today what's left over apparently are these – these pesticides. How possible is it to change the system and only allow organic agriculture inside wildlife refuges which is the case back in 1903, it was organic agriculture?

CONNOR: I think it's very possible there are already refuges that practice organic and pesticide free agriculture, and least for my purpose, the concern here isn't with agriculture as a practice, the concern here is with the pesticide use. The Fish and Wildlife Service who manages these lands definitely has the authority and has the ability to make this change, they just have to have the will.

CURWOOD: Hannah Connor is a Senior Attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity and author of the study titled, "No refuge: How America's national wildlife refuges are needlessly sprayed with a half million pounds of pesticides each year." Hannah, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

CONNORS: Anytime, thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- Center for Biological Diversity :“No Refuge: How America’s national wildlife refuges are needlessly sprayed with nearly half a million pounds of pesticides each year”

- The National Wildlife Refuge System is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- Hannah Connor’s bio on staff page of Center for Biological Diversity

Copperheads at Shawangunk

A copperhead snake slithers under a ledge. (Photo: Jay, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From wildlife refuges, we head to a protected and much loved area of New York State, the Shawangunk [SHAW-gunk] Mountains, and the Trapps, a formidable rock face. Intrepid climbers attempt to scale this vertical wall year-round. That’s not something that tempted our Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, who admits to being terrified of heights. Snakes, on the other hand, don’t bother him.

Mineral Rights

Three Copperheads at the Shawangunks

© 2017 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: Facing the rising sun, the Trapps are like the walls of a mythical fort, a couple of hundred vertical feet with overhangs and by and large an absence of vertical cracks. Climbing here has its risks.

Instead (like many high places) you can reach the top by trailing along the slope. And walk, and enjoy the view, and only have to contend with fear of heights instead of fear of falling.

On the northern part, where the mountain flattens out is a place where the bedrock is exposed like missing patches of hair. Stunted conifers cling there to where the stone is cracked, where they have purchase against storms. The shape – though not the stature of mature trees, they look not close but distant, a sparse and remnant forest in miniature. Between the green of the trees, from a deep crevasse, cold rolls up like invisible smoke. Even though it is summer now ice holds below.

A dizzying climber’s-eye view of “The Gunks” climbing wall. (Photo: Lin Pang)

Off the bare rock, in the leaf litter under the scrub oak, is the daybed of a black bear.

A pair of antlers lies moldering nearby where a buck dropped them the previous fall. Tooth marks of small animals mean the antlers are not going to waste. They never do.

Through the oaks and the bigger pines, and still higher on the ridge, again the mountain is scraped clean. The clean place ends in another cliff, this one looking west. From the edge, rolling valleys and lakes extend until lost in the bluish distances. Between the edge and the view a gorge dives down to a floor strewn with squared gray blocks, and the far cliff, some hundreds of feet away is the doppelganger of the near one. The force that split them apart is hard to imagine.

The morning sun is warm.

The silence profound.

Something moves…

Three copperheads lie half entwined on a shelf of stone. They are slow, and smooth, much smaller than the timber rattlers that also live up here. It is a rarity to see any of them. A tongue flicks out. The slight ssssss of scales against the hard surface. They back away very slowly and without making any threat except for the fact of their retreat. All they want is to be left alone.

At the last moment before the copperheads disappear under the ledge and into the shadows a glint of sunlight catches an eye, the iris glowing like lacquered copper, and that vertical slit in the center where light enters, but cannot escape.

CURWOOD: That’s our explorer-in-residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- About Shawangunk Ridge

- USGS: Geology of the Shawangunks

- Living on Earth Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender’s website

[MUSIC: Natraj, “The Ride, Part 1, Introduction” on Song Of the Swan, composed by Scarff, arr.Scarff/Jerry Leake, Galloping Goat Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, race and public beaches. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies – combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Natraj, “Miato Bebevlawo’ on Song Of the Swan, West African traditional/arr.Scarff and Mat Maneri, Galloping Goat Records]

Free the Beaches: Desegregating America’s Shoreline

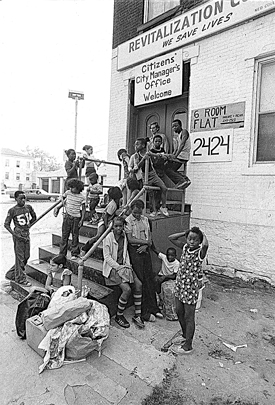

Members of Ned Coll’s Revitalization Corps march for open beaches in the town of Old Saybrook, Connecticut, 1975. (Photo: courtesy of Bob Adelman)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Back in 1959 a physician in Biloxi Mississippi led a group of black people onto a segregated beach to protest discrimination. The protestors were repulsed by white homeowners and the police, but the “wade in” – as it was dubbed, became part of the civil rights movement not only in the deep South but also in the North.

Connecticut and other northern states also had a long history of wealthy white folks barring people of color and the less affluent from their sandy shorelines. So in the 1960s the Connecticut beaches on Long Island Sound became the target of wade-ins, often led by activist Ned Coll. Historian Andrew Kahrl has written a book titled, Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline. Andrew, welcome to Living on Earth!

KAHRL: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Please describe for us briefly what the beaches were like along the Connecticut shore in the 60s and 70s, and who got to use them?

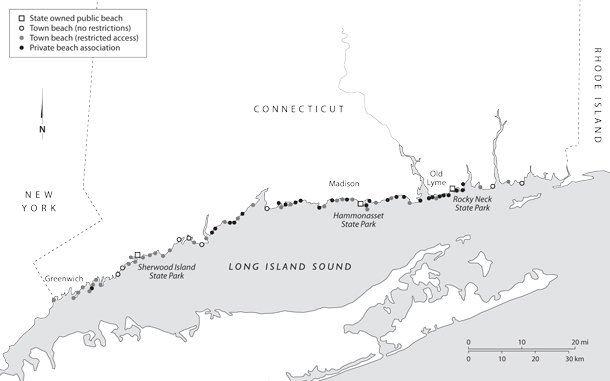

KAHRL: Well, they were very limited in their public access. It was a 253-mile shoreline, 72 miles of it was white sand beaches, and of that only seven miles were open to the public. The rest were in the hands of private homeowners, private beach associations, which were sort of like gated communities, as well as clubs and other residential corporations. So, it was, it was a shoreline that has, was effectively off limits to the general public. It was something that really was exclusive to the upper-middle class and wealthy communities that were fortunate enough to live or own summer cottages along the shore.

CURWOOD: So, on to this scene of unequal beach access comes Ned Coll. Who was he and what led him to lead a campaign to free the beaches?

KAHRL: Yeah, so Ned Coll was a young white Irish Catholic, recent college grad, who in 1964, he was working in a comfortable job in the insurance industry in Hartford, Connecticut, and had. You know, was very distraught after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, sensed that spirit of a kind of new frontier of volunteerism of civic engagement was in danger after his death, and quit his job and decided to found an anti-poverty organization called Revitalization Corps. It was – he fashioned it as a domestic Peace Corps that aim to get middle-class, white Americans, primarily those who sort of were living in sort of relative privilege and comfort to become more involved in solving the problems of poverty, of segregation and of racism in America.

Names, locations, and legal status of public beaches along Connecticut’s Gold Coast. (Image: Andrew Kahrl)

He came to the issue of beach access almost by accident. He and the volunteers, many African-American mothers who lived in the communities where he was serving wanted to sort of find ways to get children out of the city during the summer, give them more cultural enrichment activities, whether it be trips to the countryside or other excursions, and they just decided during the summer of 1971 that they would start leading trips down to the shore. They didn't think of it as a protest at all. They thought of it as just another sort of activity that they could do during the summer when kids are out of school. They loaded up a bus of children and mothers and headed down to the state shoreline and discovered that there was very little access available to them. There was few places that they could actually go, and the beaches that they did try to access, they were not welcomed at.

CURWOOD: Hey, remind us how much access that poor black kids growing up in public housing in the 60s and 70s had to places where they could play or cool off on hot summer days there in Connecticut, whether it's Bridgeport or Hartford or whatever.

KAHRL: No, this was a real serious issue. I mean, this was something I talked a lot about in the book is how the summer season really brought a whole host of injustices and deprivations into focus, and it was oftentimes as a result of tragedy. There was a shockingly high number of children in cities like Hartford and Harlem in many cities across the country that would would drown each summer oftentimes playing in unsupervised bodies of water and they were there because there was few other options available. This was something that the Kerner Commission which studied civil disorder in the 1960s and looked to sort of understand the roots of African-American unrest found that, in fact, recreation and the sort of lack of decent and safe places of recreation ranked very high on the list of African-American grievances in some of the cities or racked by violence during these years.

CURWOOD: What did the law say about the public right to access the beaches and where did the idea that beaches belong to everyone come from originally?

KAHRL: Yeah, I mean the idea that the shoreline belonged to the public originated in the Roman Empire. In the year 530 C.E. the Roman emperor Justinian proclaimed that shorelines are common to mankind, that they’re subject to the same law as the sea itself and that no law one can be forbidden from approaching them.

This idea what's later became known as the public trust doctrine has deep deep roots in western law. It formed the basis of the English common law, this notion that beaches were public land and then it became part of American common law with the founding of the Republic. So, this notion that beaches are public property has deep deep roots in American law.

CURWOOD: So, Ned Coll begins really a campaign to free the beaches and he takes this busload of kids and mothers down to the shore and there's not a lot of access. What's the turning point when he decides, hey, I need to make this a cause?

KAHRL: Yeah, really I think you can sort of date it back to that summer of 1971 when they went to the town of Old Lyme, Connecticut, which was one of the many old, upper middle class wealthier communities along the shore, and were greeted very hostilely by the homeowners who felt as if, this was their private beach, this was, they were trying to sort of access what was a private beach association's shoreline. The sort of anger and hostility that greeted him really unnerved him and woke him up to some of the realities of racism in these places that had not really been on their radar. I mean, these are isolated small, sort of little summer enclaves of people of sort of great privilege and it turned his attention to seeking to first engage with these communities and as they became increasingly resistant and hostile to his very presence, seeking to sort of protest and draw attention to this issue.

CURWOOD: There's a passage from your book that describes one of his demos, if you could call that. It's an amphibious invasion of one of these beaches. Could you please read from your book there? I think it's page 187.

KAHRL: Yeah, sure.

On the ride to the shore the kids could barely contain their excitement it would be a Fourth of July to remember. As the Long Island Sound came into view, the vans pulled into the boat landing located next to the private club whose festivities they would soon be crashing. Ned and one of his assistants leapt out of the van and began unfastening the boats from the roof and dropping them into the water. Someone else hung a ladder off the pier.

Once everything was in place, Ned and the volunteers scurried down the ladder and into the boats. The children strapped on their life jackets, climbed aboard the vessels and headed out to sea. On the shore members of the exclusive Madison Beach Club who underwent a rigorous vetting process and paid a $300 annual membership for days like this were trickling out onto the beach and planting themselves underneath one of the club's neatly arranged green umbrellas. Just before noon, three boats appeared, all headed toward the club shore. Ned, with an American flag attached to a pole, leaped off the bow and began marching, MacArthuresque, toward the beach, stopping just before he reached the dry sand he shouted, "Happy Fourth of July everyone," and defiantly planted the flag in the sand.

Children and staff outside Revitalization Corps’s headquarters on Hartford’s North End, c. 1975. (Photo: courtesy of Bob Adelman)

Moments later a plane began circling overhead carrying a banner that read, "Free America's beaches". Club members stared in disbelief. This was an ambush. Parents sqooped their children off the beach and made a hasty retreat to the clubhouse.

CURWOOD: Sounds like those folks were scared.

KAHRL: Yeah, in a sense, it was kind of unlike anything they had ever seen before because the shoreline in many of these towns had been so effective in the limited public access, and not just limiting public access to the beach, but also sort of limiting diversity within their communities. I mean, one of the things that I talk a lot about in the book is the way that many of these towns had and acted exclusionary zoning ordinances that prevented low-income housing or really sort of preventing anyone below a certain income level from being able to live in these towns. So, these were virtually all white and very sort of class homogenous as well. So, the very presence of a busload of children from inner city Hartford was unthinkable for them.

The one thing that I think that really sort of stood out to me especially as someone who had who had previously studied desegregation of shorelines in the South during the civil rights movement at a time where there was horrific violence characterized by efforts to desegregate beaches, you know, wade-ins that took place where mobs of white segregationists would come out into the water with baseball bats and tire irons and violence would sort of erupt. Here in these sort of very well-to-do communities, oftentimes the response was to simply sort of retreat to the clubhouse, remove their children. That was really one of the saddest things is that white and black children would be playing together here on the shore and parents would grab their children and sort of take them away as if that this was some sort of threat to them. At first they sort of reacted with a degree of shock and then anger and hostility as they realized that Ned wasn't coming there seeking permission. They were coming there as asserting their right to access this beach whenever they pleased.

CURWOOD: Now, after a while, of course, there’s litigation, and the advocates for freeing the beaches move ahead, in many cases in court. What stands out as most significant among those cases?

KAHRL: The protests that Ned Coll and others were waging in Connecticut dovetailed with this open beaches movement, which was really national in scope, and from one 1970 to 1980, there were over 150 beach access cases heard in state and local courts. That's up from 10 the previous decade. One of the issues that many of these cases challenged was the right of local communities that had accepted substantial amounts of state and federal tax dollars to help build and enhance their shorelines. Whether they could limit access to residents only when it was really everyone who had helped to pay for these facilities. Now, the interesting thing that happened in Connecticut was the way that very wealthy towns like Greenwich and Madison interpreted these cases was to say, well, the solution for us is to never accept state or federal tax dollars, and they were wealthy enough that they could do that. And so Greenwich in particular developed almost a phobia of any outside funding that was being dangled before them fearing as if it would be some sort of poison chalice that would then lead them into court.

CURWOOD: You write that when some of these communities who were forced to open up their shorelines "to the public" that they found some rather ingenious ways to – and I say that in the diabolical sense of the word –

KAHRL: Mmhmm.

CURWOOD: to nonetheless keep people out. Can you give me some examples?

KAHRL: Yes, so in 2001, the state of Connecticut, the state Supreme Court declared that the restrictions that Greenwich and many others communities were using that explicitly barred nonresidents from accessing their shorelines was unconstitutional. So, at that point legally the beaches were open to everyone, but towns were finding new ways to sort of get around this, and so it could either be through very limited parking access or say having parking lots that only residents could park in. Selling beach passes in a way that was – made it very difficult for non-residents to actually purchase them, but oftentimes, on this issue in particular, there was a real effort to distance ... these communities really stressed that their beach access policies had nothing to do with race. It was simply a matter of private property rights, of the rights of local communities to limit access to residents only, and even went so far oftentimes in a very cynical way to acclaim that they were restricting access out of environmental concerns, that they were fearing that if they letting anyone on to the shores then the shores themselves would be harmed.

CURWOOD: So, basically nature designed the beaches, the coastal areas to be dynamic. That at times the coastline would receded, at other times it would advance. What has all this privatization of beaches done for our ecology do you think, and the lesson we might be able to learn?

KAHRL: Yeah, you're absolutely right. I mean, beaches exist in a state of dynamic equilibrium. They're in constant motion. They resist any attempt to sort of stabilize and yet that is sort of the story of coastal America in the 20th century was this constant effort to try to sort of hold beaches in place, whether it be through sea walls, beach nourishment projects. I mean, we spent millions of dollars a year pumping sand onto shorelines in the interest of sort of making them attractive to vacationers or to homeowners and yet much of this is not only sort of is oftentimes quite literally washed out to sea when a storm hits but as well makes the sort of problems that sea level rise poses all the more daunting and pushes us further away from a more sensible and more sustainable relationship with these very fragile stretches of land.

Andrew Kahrl is an associate professor of history and African American studies at the University of Virginia. (Photo: University of Virginia)

And one of the problems that I see ... this was plainly evident after Superstorm Sandy in 2012 was a reluctance to face up to the reality and to heed the call that many coastal scientists have been issuing for years now, which is that we need to begin to retreat from areas that are highly vulnerable to sea level rise and will be uninhabitable, and yet we consistently resist that and instead double down on development and double down on rebuilding. And what drives this? Well, in part it's that ability to be able to sort of colonize the shore and claim beachfront property as your own. This is highly desirable real estate and it's made all the more desirable by the ability of homeowners to be able to not just sort of enjoy the spaces but also to restrict access to others.

CURWOOD: You're an academic, you're not a judge or jury, but how would you rate Ned Coll’s success in his enterprise to try to desegregate Connecticut's beaches?

KAHRL: Well, I think it's undeniable that the activism that he engaged in in the 1970s raised awareness of not just the issue of beach access, but of a larger set of inequalities that were shaping life in the northeast and across the country. For a time Revitalization Corps was really truly national in scope. It spawned hundreds of volunteers, dozens of chapters across the country. People really were drawn to his spirit of civic engagement and sort of local activism, but ultimately it struggled to make long-term gains because of Ned's reluctance to sort of work with others, and to sort of partner with other organizations and to really put in place an infrastructure that would allow communities to organize themselves, and because he was so single-minded in his focus and so adamant in his beliefs, and the issues he cared deeply about that it was oftentimes sort of his way or the highway.

Now that said, the gains that have been made with regard to public beach access are significant. I think that the decision in 2001 by the Connecticut Supreme Court that opened up the state's shoreline to the public could not have been possible were it not for the activism of Ned Coll in the 1970s. But we still see across America this steady trend toward closing off public access and of increased sort of retreat amongst many Americans into private spaces, and that really poses a threat to our democracy as a whole. I mean, as I argue in the book, public space plays a very essential role in a democratic society. These are sort of places where people of different backgrounds, races and ethnicities and income levels can come into contact with each other and really in the process learn how to get along and when we don't have that it leads toward increased polarization, increased division, increased parochialism, and I think the cause that he was championing is an important one that still remains very much with us today.

CURWOOD: Andrew Kahrl teaches history and African-American studies at the University of Virginia. His book is called "Free the Beaches." Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

KAHRL: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Free the Beaches book

- About Andrew Kahrl, Associate Professor of History and African American Studies at the University of Virginia

[MUSIC: Summertime (Instrumental) DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RzEP6BPrLVs]

CURWOOD: Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Hannah Loss, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Aynsley O’Neill, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org – and like us, please, on our Facebook page – PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth