March 23, 2018

Air Date: March 23, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

FEMA Flood Maps Miss the Mark

View the page for this story

The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s “patchwork quilt” of flood maps has coverage gaps, and is obsolete in places, according to a recent study by the EPA, Nature Conservancy and UK University of Bristol. The new study finds 40 million Americans are actually at risk from floods, rather than just the 13 million people who populate FEMA’s official flood zones. Kris Johnson of The Nature Conservancy tells host Steve Curwood that better maps could also save lives, homes and nature by discouraging development in flood-prone open spaces. (11:20)

Coastal Republicans Fight ‘Drill, Baby, Drill’

View the page for this story

In January the Trump administration announced plans to open nearly all US coastal waters to offshore oil and gas drilling. Since then governors and legislators of both parties including Republican Nancy Mace, have strongly opposed drilling near their coasts. Nancy Mace, who represents parts of Charleston County and the Low Country in the South Carolina House, tells host Steve Curwood that she campaigned for Donald Trump, but oil rigs off South Carolina’s beaches would be a disaster. (07:11)

Trouble Today for Ancient Fossils

View the page for this story

A thick bonebed of Triassic era fossils was recently discovered within Bears Ears National Monument. But the Trump Administration has slashed the Monument’s size, leaving the site more vulnerable to vandalism. Paleontologist Rob Gay explains to host Steve Curwood that the fossils provide vital clues to the past but the new Monument boundaries jeopardize future research and excavation. (09:08)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood checks in with Peter Dykstra to look Beyond the Headlines. This week they note the Norwegian oil company Statoil’s name change, cherry orchards that are using birds instead of pesticides, and from the history vaults, plaintiffs take a case against DDT to the US Supreme Court. (04:14)

A Waddle of Penguins

View the page for this story

Researchers recently spotted a supercolony of some 1.5 million Adelie penguins on the aptly named Danger Islands in Antarctica with the use of satellite technology. Host Steve Curwood discusses the significance of this discovery for the Adelie population with P. Dee Boersma, conservation biologist at the University of Washington, and asks why she and many other people find these birds that fly through water so irresistible. (10:33)

Stealing Dirt: A Thieving Penguin

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Visiting the Falkland Islands, writer Mark Seth Lender watched Gentoo penguins building nests from mud, the only material available. But one male wanted stickier dirt from a neighboring colony whose members objected. Still, his mate appreciated the mud and him. (03:14)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Kris Johnson, Nancy Mace, Rob Gay, Dee Boersma

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. West Virginia. Ohio. South Carolina. Texas. They’ve had devastating floods but FEMA maps understate the risks.

JOHNSON: You know, here we are in 2018 and we have essentially kind of a patchwork quilt of flood risk information for our country. There are places where we have very good, up-to-date information but there are also many places in this country where we have no mapping at all.

CURWOOD: How filling the gaps could help save lives, property and nature. Also, why we like penguins.

BOERSMA: They walk upright, they're curious, they’re cute, they’re industrious - I just don’t think there’s anything not to like about penguins unless you’re trying to grab ’em and then they bite you! And then there’s a good reason not to like them but of course, they don’t want to be grabbed!

[SOUNDS OF JACKASS PENGUINS]

CURWOOD: A waddle of penguins and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

FEMA Flood Maps Miss the Mark

Hurricane Harvey brought intense downpours to the Houston area in August 2017, precipitating severe flooding. (Photo: Tom Fitzpatrick / World Meteorological Organization, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. With all the extreme weather we’ve had lately, it seems important to know if one could get flooded out when hard rains fall and rivers rise. But if you rely on Federal Emergency Management Agency or FEMA flood maps, you could get false comfort.

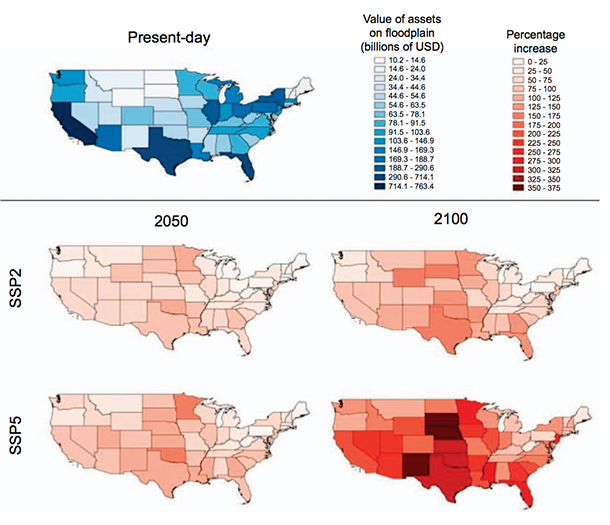

New research using high tech analysis finds some 40 million Americans live in areas where there is a one percent risk of a flood in any year—a so-called hundred year flood--but FEMA flood maps indicate only 13 million or so face that risk. And the research team made up of folks from the UK University of Bristol, the U.S. EPA, and The Nature Conservancy, projects that by the middle of the century, 60 million Americans will be at risk of such floods, unless land use and planning change. Kris Johnson of the Nature Conservancy is a coauthor of this study. And Kris – this does not sound like good news for people who live near big rivers or even small streams.

Maps depicting the value of assets within the 1 in 100 year floodplain, split by state. The ‘current’ map (blue) indicates the absolute value of assets within each state’s floodplain. The ‘future’ maps (red) indicate the proportional increase in exposed assets from the present-day to the respective year under a particular scenario. (Image: Fig. 4, “Estimates of present and future flood risk in the conterminous United States,” Oliver E J Wing et al 2018)

JOHNSON: Well, you're right. It's not good news that we find out that there's many more people, many more buildings, much more property in harm's way from flooding. But it is useful information, right? It's important that people know. It's important that we as a country have a much better picture of where the risk really is and how significant it is, and right now there is sort of a bright line, in-or-out approach to flood insurance.

There are FEMA maps, where they exist and where they're available. If your property is within this so-called 100-year flood plain – the boundaries of this one percent chance flood event, well then, if you have a federally-backed mortgage you need to buy flood insurance to protect yourself and your property. If you're not within that, if you're just on the other side of that line, well then you don't need to buy any insurance and you're essentially being told that you're not at any risk of flooding, which we know is not true. And so we need a more comprehensive and proactive and sort of integrated approach to thinking about risk because as our study shows, there are many many more people who are probably in harm's way than we had originally thought. We know right now that there are five-and-a-half trillion dollars worth of assets that are at risk from a -- what we call a one percent chance flood, or a 100-year flood. You know, We need to address that we need to mitigate that and more importantly we need to not put any more people or property or assets in harm's way in the years to come because that will only make that price tag even bigger.

CURWOOD: Kris, what got you and the Nature Conservancy interested in studying flood mapping?

JOHNSON: Yeah, well that's a great question. You know, we focus heavily on conservation, but we're also really interested in how conservation and protection of open spaces can not only provide benefits to nature, but can also provide benefits to people, and studying rivers and river management and flood plains over the years, what we came to understand is that there's actually a pretty exciting sort of win-win opportunity in flood plains, and that is that if we protect and restore these places that are ecologically and hydrologically really important – they provide habitat for birds, they support spawning of fish, they store carbon and they help reduce flood risk – so we can protect these places that provide these environmental benefits and at the same time we can actually help reduce the impacts, you know, to people and to property.

CURWOOD: And so, what was the moment that you decided or your organization’s decided, hey, we really ought to figure out what's going on with these flood maps?

JOHNSON: Well, we tend to think big picture. You know, when you're grappling with sort of complex environmental challenges, you don't just look at one particular place on a map. You think about sort of regions and ecosystems and watersheds, and what we discovered is that the history of flood risk management has very logically gone sort of place by place and piece by piece. That's really kind of a function of how our science, our modeling, our engineering approach to understanding flooding has evolved, and it is also is sort of a function of our institutions, our local units of government, and the way in which they manage flood risk. And the problem with that is that here we are in 2018 and we have essentially kind of a patchwork quilt of flood risk information for our country.

There are places where we have, you know, very good, very detailed up to date information about where we think flooding is most likely to happen, but there are also many places in this country where we have no mapping at all, or you know, there may be towns and local municipalities that are still managing their flood risk off of paper maps that were drawn up 20, 30, 40 years ago. And so from the Nature Conservancy's point of view, this new modeling approach really gave us the ability to develop these floodplain maps at a much bigger scale, which helps us think about risk and it also helps us think about managing the environment in a more integrated way.

Rivers are naturally dynamic, meandering back and forth across a landscape. In the above satellite image, the small, blocky shapes of towns, fields, and pastures surround the graceful swirls and whorls of the Mississippi River, the largest river system in North America. Countless oxbow lakes and cutoffs accompany the meandering river south of Memphis, Tennessee, on the border between Arkansas and Mississippi. (Photo: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/USGS)

CURWOOD: Now, as we mentioned at the beginning of the segment, your study findings would indicate that there are millions of homeowners and commercial building owners out there that don't understand that their at risk from flooding because the FEMA mapping hasn't shown them to be. So, what can those folks who are concerned do to find out whether in fact they are at risk?

JOHNSON: I would say for any sort of, kind of aware and proactive and concerned property owner or homeowner, take a look at your local city and town and find out, you know, what the floodplain maps show for your area and find out when the flood map was created, and try to understand how good the information is for your neck of the woods. In many cases, if you live in a large city the flood plain maps and the flood risk information is probably pretty good, but of course, we all know that risk is changing as more development happens, as climate change moves forward, flooding is becoming, you know, increasingly severe, increasingly significant. We don't fully understand all the ways in which that may change everywhere, but we know that this problem is only growing.

So, if you're near a floodplain, on the edge of a floodplain, if you're not sure, talk to your insurance agent, find out what policy options might be available for you. I mean, the good news is if you're not within a current FEMA flood zone, you could probably add a flood risk reduction part onto your policy for probably, you know, fairly little expense.

CURWOOD: Looking back over this last very wet season – the Harvey, the Maria, the Irma – how did your study’s findings compare with places that flooded out that frankly hadn't been expected to flood out?

JOHNSON: Well, one thing I should say is our study focused really on riverine flood risk – non-coastal flood risk – basically. Some of the flooding that we see in coastal areas due to storm surge, due to increasingly rising sea levels, that flooding isn't something that we tried to map or model with our study. But I will say that in a couple places, for example, in Houston, many of the areas that were inundated, that did get flooded during that events, they do show up on our maps as places that you might expect to be flooded during a big event.

CURWOOD: So, to what extent did you factor in potential climate change impacts in your analyses?

JOHNSON: As I mentioned earlier, we know that the climate is changing and we know that that change is going to have real implications for flooding, for rainfall and for impacts on people. We also know, unfortunately, that it's going to be really varied from place to place. Some parts of the country are likely going to get wetter and more intensely impacted by flooding, whereas other places, you know, we may actually see risk from this kind of flooding diminish over time.

Texas National Guard soldiers aid citizens in flooded Houston, Texas in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, August 2017. (Photo: Lt. Zachary West, 100th MPAD / Texas Military Department, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

So, our current study doesn't incorporate that. That would be sort of coming down the road hopefully for us scientifically. So, what we did instead is we used our current understanding of where flood risk is and then we looked ahead at where the Environmental Protection Agency thinks that people might continue to move and develop property, and so we know that even if flooding doesn't change from what it is today, in 2018, we know that people are unfortunately going to continue to develop in harm's way and we project by 2050, there will be you know, upwards of about 60 million people at risk from a one percent chance flood event, a 100-hundred year flood event in the U.S.

CURWOOD: And so those 60 million people, you project would be living in relatively high flood risk areas you make that projection without including climate disruption, you make that projection not including possible storm surges in coastal areas.

JOHNSON: That's right, that’s right.

CURWOOD: So, at the end of the day, the risk would be maybe not quantifiable but larger really than what you're saying.

JOHNSON: I think that's right, I think that's right. And the other thing to keep in mind is that, of course, if people do develop in these areas, typically as a society we feel some understandable obligation to protect them against floods, and so that in turn would mean potentially building more levees, building more flood walls, more flood defenses, which of course cost taxpayer money and not only that but when you defend a particular place against a flood event, you push the water downstream faster, essentially. And so you can likely exacerbate flooding somewhere else in the system if you're really defending a particular place against a flood. And so, how we respond to this increased flood risk, how we respond to increased development, that may make the problem even worse in some places.

Kris Johnson is an Associate Director for Science and Planning for The Nature Conservancy’s North America Agriculture Program. (Photo: The Nature Conservancy)

CURWOOD: Because what you described happened after the huge floods along the Mississippi in the 1920s a century ago, they built all these levees and that just moved the water downstream at a faster velocity, where people further south now get pretty serious flooding.

JOHNSON: That's exactly right and you know, you would think we would have more fully learned our lesson in the 100 years since those big events. You know, rivers need – they need room to roam. Big events come and they move from side to side and we need to sort of resist the temptation to farm right up to the banks or to put our houses and buildings right up to the banks because sooner or later an event, you know, is going to happen and that's going to put those properties in at risk.

CURWOOD: So Chris, how much undeveloped space is there still along waterways?

JOHNSON: Well, you know, we're still finishing up some analysis in another paper that will really quantify that, but looking across the U.S., across all of our rivers and streams, initial estimates are something on the order of about 800,000 square kilometers of open space in flood plains that could someday potentially be developed. It's certainly not all going to be developed, but these are places where we should really look hard and consider, you know, some protections, some zoning, some better planning, to make sure we don't develop in these places and don't increase risk to people or property.

CURWOOD: Kris Johnson is an Associate Director for Science and Planning at the Nature Conservancy. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today Chris.

JOHNSON: Thank you.

Related links:

- The study in Environmental Research Letters: “Estimates of present and future flood risk in the conterminous United States”

- CityLab: “New Report Says FEMA Badly Underestimates Flood Risk”

- Bloomberg: “FEMA Strips Mention of ‘Climate Change’ From Its Strategic Plan”

- FEMA Flood Map Service Center

- Kris Johnson’s The Nature Conservancy profile

[MUSIC: Jan Johansson, “Visa fran Utanmyra,” on Jazz Pa Svenska, Heptagon Records]

CURWOOD: If you like what you hear on Living on Earth, please join us with a gift of five dollars or more. Just go to Loe.org and click on “donate” at the top of the page – and thank you!

CURWOOD: Coming up, ‘Drill Baby Drill’ is getting bipartisan pushback in oceanfront states. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, keep listening!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jan Johansson, “Visa fran Utanmyra,” on Jazz Pa Svenska, Heptagon Records]

Coastal Republicans Fight ‘Drill, Baby, Drill’

South Carolina’s beaches and tourism are an important source of income for the state. (Photo: Loadmaster, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. In January the Trump administration announced plans to expand offshore oil and gas drilling to nearly all of the US coastline. Since then, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke has said he would exempt Florida from offshore drilling. And that has prompted a growing number of Republican and Democratic Governors and legislators from coastal states to demand the same exemptions well. One of them is Nancy Mace, a Republican state representative from South Carolina whose district includes parts of Charleston and the Low Country. Nancy Mace, welcome to Living on Earth.

MACE: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Why are you concerned about the oil and gas drilling?

MACE: You know, when we have a $20 billion dollar tourism industry that employs 600,000 people annually, people don't come to Charleston or anywhere along the coast to look off our coasts and see oil drilling. They come for our beautiful beaches. As the governor said, “These are shores lined with gold.” They're absolutely stunning. We have beautiful live oak trees, good people, good food, and that's why people come down here and not to see offshore oil drilling.

Obviously, there are environmental concerns, what happens to the fish out there and mammals as the Department of Interior has already stated at least to some degree. South Carolina did seismic testing off the shore in 1977. They didn't find anything then, they're not going to find anything now, so why are we doing this? Why are we going to disturb what's out there? And then you have commercial fishing ... that's going to disturb that industry as well. And so, when you talk to every municipality along the coast, this is not something any of them want.

CURWOOD: But now what about the interior of South Carolina?

MACE: Right. I think there's a lot of support for offshore seismic testing and oil drilling in inland and the upstate because it ain't in their backyard. They don't have to deal with it. They don't have to see what's going to happen.

CURWOOD: So, to what extent is this a NIMBY, not in my backyard issue? That it's OK for say other states like Louisiana or in your state even, folks upstate are saying that it's okay to have this but you don't want to have tar balls rolling up on the beach.

MACE: We've got plenty of tar balls elsewhere in this country. I don't think we need to create new ones, so...

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] What concerns do you have about the cost of the infrastructure to support offshore drilling?

MACE: Well, we have issues now. I can barely get a road re-striped in my district right now, let alone widened, and this is on a road that has 89,000 vehicles per day – some of the most in the state. And so when we can't do for ourselves for economic development reasons – ’cause this is a road that comes right out of one of our terminals at the port – then we certainly can't even think to take this on right now. It just is not going to happen from a fiscal standpoint. We don't have the money.

Rain and high tides regularly cause flooding in Charleston, South Carolina. (Photo: NOAA)

CURWOOD: To what extent is this a states’ rights issue?

MACE: I think it's the number one issue. I mean, when Ryan Zinke gave Florida a hall pass and allowed them to opt out of this federal issue, well then that opened the door to states’ rights. So, you can't do for one and not allow the others to opt out. I mean, essentially Congressman Mark Sanford, that's his number one take on this issue, is that issue of federalism.

CURWOOD: You know, it wasn't too long ago that the former head of the Republican Party famously said, "Drill, baby, drill." I thought that fossil fuel extraction is the shibboleth of the Republican Party. What's going on?

MACE: Well, I don't necessarily disagree. I mean, we want to do the pipeline in Alaska, but now we're exporting, right, and so I don't see at the Federal level that great of a need right now to try and find more oil out there, particularly along the coast of South Carolina. I don't see the need.

CURWOOD: Now, as understand it, you supported Donald Trump, you campaigned with him…

MACE: Correct.

CURWOOD: … and you helped him get elected there in South Carolina. How do you feel about the Trump's environmental agenda, given this development?

MACE: Well, I am my own person. I'm my own woman. I have my own ideas, and I'm proud of the work that I did on Trump's presidential campaign when it came down to it. We had two choices, and I knew which one was better, but that doesn't mean I'm going to be like a blind sheep and follow hook, line and sinker. I have my own ideas. I represent a district along the coast in South Carolina, and I'm going to look out first and foremost for my constituents.

CURWOOD: Some people say we don't need to drill for this oil because it’s more fossil fuel burned means faster sea level rise, that sort of thing. To what extent do the concerns about climate factor into your concern about this drilling?

MACE: I haven't looked at it from that perspective, and I'm not a climate change sort of person. I see this issue being a bipartisan issue that I can get behind for a number of reasons. One being the issue of federalism. Two being the cost prohibitive nature of the inland infrastructure. Third being the environment. We do care about our coasts down here. We do care about our environment. There's so much development going on in the Charleston area. We have 47 people a day that moved down here to this area, and so we have a lot of development and growth issues, and that's where my heart is what can we do to preserve what we have now if we develop it all away, it's going to be gone, and there's going to be no reason for people to come and visit.

CURWOOD: What are the flooding risks right now there in the Low Country of Charleston and in the islands?

MACE: If it sprinkles, it floods. So, the city of Charleston is actually built on ... the peninsula itself was built on a landfill, and that landfill is sinking. I mean, that's not strong ground to be on, and so we do have our own issues of flooding, not just on the peninsula but throughout the Low Country. It is it huge problem for us for various reasons. We have a lot of marshes and marshland. Where I personally live it was built on a marsh, so any time we have a hurricane or a big storm, flooding it's always going to be a concern for the residents of the Low Country.

CURWOOD: To what extent might you look into the climate effects the flooding there in the Low Country and how might that inform policy?

MACE: I won't. It's not part of my agenda. I see that as more of a federal issue, and I'm trying to tackle what I can at the state level, which right now particularly that's infrastructure. We have a nuclear power plant, 9 billion dollar nuclear power plant mess. It's about 50 percent built. The contractor has bailed and gone bankrupt and ratepayers are left holding the bag. We're trying to walk ourselves out of that. And then the offshore drilling issue came up because it's a bipartisan issue that many of us are very upset about and want to do what we can. I'm still waiting on my simple House resolution that just says we're against this as a body to get a hearing, and it hasn't yet. So, we have some work to do down here.

South Carolina State Representative Nancy Mace serves District 99. (Photo: Jm817, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: It sounds like old-fashioned Republicans who were into conservation back in the day. What's going on?

MACE: Right. No there are. I would say that there is a caucus of Republicans who care about the environment, who care about these issues. They want to do what's best. And this is an issue that I think both the Republicans and Democrats can come together on. And in this era right now that we're in right now, that's quite a good thing in my opinion.

CURWOOD: Nancy Mace is a state representative for South Carolina's 99th district that includes the city of Charleston. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, representative.

MACE: Thank you so much for having me. Have a great day.

Related links:

- The Washington Post: “For many Republicans, Trump’s offshore drilling plan and beaches don’t mix”

- Nancy Mace website

- U.S. Department of the Interior: “Secretary Zinke Announces Plan For Unleashing America’s Offshore Oil and Gas Potential”

[MUSIC: Glen Velez, “Pan Eros” on Pan Eros, CMP Records]

Trouble Today for Ancient Fossils

Phytosaurs hadn’t been found in Utah before this discovery. Paleontologist Rob Gay describes these creatures as “alligators with blowholes.” (Photo: The Carouselambra Kid, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now for Native Americans, the Bears Ears region in Utah, with its towering mesas and red rock canyons, is sacred ancestral land. Over 200 million years ago, giant reptiles wandered in Bears Ears leaving a vast cache of recently discovered Triassic-era, fossilized bones. In December 2017, President Trump reduced the size of the Bears Ears National Monument by 85 percent, just one year after its designation. The move favored the potential for oil and gas exploration, but has left paleontologists like Rob Gay worried about the fate of the region’s rare fossils. Rob works with the Museums of Western Colorado and joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Rob.

GAY: Thanks. Glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So, tell me the landscape. What does it look like around Bears Ears?

GAY: So, I've heard it described before as a classic western American landscape. If you look on the HBO show Westworld, some of the scenes there were filmed near this area. A lot of classic Westerns from the ’50s and ’60s have also been filmed in the Bears Ears region just to the south in Monument Valley as well as in Valley of the Gods. You have red cliffs, open vistas, towering snow-capped mountains in the distance, high plateaus covered in low, shrubby forest and deep hidden canyons.

CURWOOD: And tell me what you found in the way of fossils at Bears Ears? And what kind of formation were they in?

GAY: So, my team and I have been looking at what's called the Chinle formation in Bears Ears National Monument for quite some time now. It dates from the dawn of the age of dinosaurs and we found all sorts of amazing fossils...plant eating crocodile teeth and we've found footprints that indicate that armored herbivorous crocodiles walked the landscape, and then most recently we came across a huge deposit of fossilized bones from animals called Phytosaurs. These are 15 to 20 foot long crocodile mimics with blowholes.

CURWOOD: Oh my, and these date back to how many million years ago?

GAY: So, the Chinle formation spans about 225 to about 200 million years ago. These Phytosaurs that we've been finding are probably about 212 million years old.

Gay estimates there are decades of work to be done researching this fossil site. (Photo: courtesy of Rob Gay)

CURWOOD: That is old. Rob, what is the significance of the fossils that you found at this excavation?

GAY: So, this site is significant for many reasons. First of all, the site is enormous. It's about 63 meters long, which makes it the largest Triassic bone bed in the state of Utah, and based on our limited excavation in 2017, the amount of fossils we're finding in there means it's one of the densest probably in the country, if not the entire world. And on top of that, the fossils that we're finding, that we've been able to identify so far, all come from an animal that has never been found in Utah before. In fact, it's only been found in the petrified forest of Arizona, and that was a recent discovery. So, it's not well known. It seems to be a very rare animal, and all of a sudden we've got the world's largest treasure trove of this animal.

CURWOOD: At risk from development now at Bears Ears now since it's not protected.

GAY: So, all federal land has some basic protection for vertebrate fossils, but within a Monument there's additional protections for not just vertebrate fossils but also for invertebrate and plant fossils. So, things like snail shells and clam shells and plants, things that help us discover what this environment was like 212 million years ago. Without a monument, anyone can come and collect plant fossils and shells legally, it's not prohibited whereas in a monument, that activity is restricted to permitted scientists.

So, there's that aspect, but there's also the aspect of development such as power lines, mines, roads, trails, and when it was in a national monument this was protected in what's called the national conservation land system which is a system of BLM lands across the west mainly, National Monuments, National Conservation Areas, National Historic Trail, things like that, and there's funding specifically set aside for Congress for scientific exploration of these National Conservation Lands. So, now that this site is no longer in a national conservation land, it's not eligible for these funding sources.

The Valley of the Gods, which is located at the southern end of the original Bears Ears National Monument boundary, is now located outside the monument following the Trump Administration’s decision to shrink the monument by 85 percent. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, part of your job as a paleontologist is a detective, right, and what do you think happened at this spot that you have all these fossils within this particular place?

GAY: So, we've got some clues, but that's one of the things we're hoping to figure out and without the funding it's going to be really difficult to perform the excavations and analyses that we need to. So, we have all of these bones and they're all generally articulated. So, that means in life position, like you'd have a skeleton in a body today, and they're all jumbled on top of one another. So, that tells us that something quickly killed these animals and then covered them over. Additionally, we know by looking at the rocks that these are preserved in a fossil soil, so this wasn't the bottom of a river or a lake or a pond. But there was certainly some water present because we also have a clamshell from this deposit. We also some plant fossils, cycads, these are a group of plants that are still around today and that tells us that this wasn't a swamp. You don't find cycads in swamps, so we're not sure what happened to these animals, but it appears that something killed these animals probably near a river, but on dry land where there are plants growing.

CURWOOD: A collective bad day it sounds like.

GAY: [LAUGHS] A very bad day in the Triassic.

CURWOOD: Rob, I know that you're a paleontologist, you're not a geologist who's involved in extraction of fossil, oil, and gas, different kind of fossils for you, but in general, what's your understanding of what the commercial potential is there? I believe people say there's oil, there's gas, even uranium.

GAY: Yes, so in the 1920s and 1930s, the area was extensively drilled, looking for oil and gas deposits. There was a concentrated effort because of some of the underlying geology of the region, and those all came up with nothing. In terms of other fossil fuels like coal, there is coal within the boundaries, but it's not in what I would imagine to be commercially mineable amounts. We're talking about coal seams that are three inches thick and extend for maybe 100 yards.

The biggest historical use of the area in terms of economic geology has been uranium, and the uranium boom of the ’50s and ’60s really fueled the development of roads into the area and ironically fueled the development of our scientific understanding of the fossils in the region because these localities and these exposures were opened up due to these uranium mining roads. There's been plenty of talk recently about expanding uranium development in the area that would severely threaten fossil resources and while that is a possibility, the fact that existing mines that are in the area are not producing uranium, tells me that the commercial value of the uranium in the ground, it's probably not too high.

Part of a phytosaur fossil unearthed by the excavation team. (Photo: courtesy of Rob Gay)

CURWOOD: So, given what's happened there – the shrinkage of Bears Ears National Monument – what would you say to someone who asks you, why is this work important?

GAY: This site is from a very interesting time in Earth's history, and not long after this site was formed there was a huge extinction – one of the major mass extinctions in Earth history. Dinosaurs survived through it. Everything else that we're finding there went extinct. So, if we can better understand these animals and the environment that they lived in, we have a better idea of understanding why dinosaurs were able to survive this huge extinction which seems to be related to the supercontinent of Pangea breaking apart and causing enormous sudden catastrophic global climate change.

CURWOOD: Hmmmm, surviving climate change, mass extinction. Sounds familiar.

GAY: Yeah, might be important to understand how that's gone down in the past.

CURWOOD: So, Rob what are your next steps for these phytosaur fossils on the excavation project?

GAY: So, I'm looking for funding to continue this work and also to continue exploration in the region. Outside of the funding stream, the next steps are to figure out what the heck we actually have, what did we pull out of the rock. So, the fossils are currently undergoing preparation at the St George Dinosaur Discovery site in St George, Utah, where they are being removed from their rocky cradles. I'm really excited to see what all comes out of there. So, we don't know what sort of animals besides this Protosuchus are in there. There is a possibility that we have new species. There's a possibility that we have animals that haven't been documented from this area or this time before. That's really exciting. That's going to take several months to get a full accounting of what is in these big chunks of rock that we brought back to the museum.

CURWOOD: Rob Gay is a paleontologist who works with the Museums of Western Colorado. Rob, thanks so much for taking the time today.

GAY: Thank you so much for having me on.

Related links:

- The Washington Post: “Spectacular fossils found at Bears Ears -- right where Trump removed protections”

- The New York Times: “Oil Was Central in Decision to Shrink Bears Ears Monument, Emails Show”

- About Rob Gay

[MUSIC: Jim Henry, “1967” on The Wayback, Signature Sounds]

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line any time at 617-287-4121, that’s 617-287-4121. Our email address is comments at loe dot org, and visit our webpage at loe dot org. That’s loe dot org. Coming up, lots of penguins, a super-colony and more! That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend from Sailors for the Sea: Working with boaters to support ocean health.

Beyond the Headlines

Michigan’s cherry crop is plagued by birds that like to eat the tasty fruits – so farmers are bringing in American Kestrels to help deter the cherry thieves. (Photo: rosefirerising, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Let's take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra now. Peter’s with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and DailyClimate dot org, and he joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there Peter, we’re getting a bit tired of the snow here in New England, what’s going on with you?

DYKSTRA: The weather’s kind of nice down here, you ought to come down. We’re going to talk about some big, big re-branding. Statoil the Norwegian oil giant, they are the 27th biggest oil company in the world in terms of sales but they’re still pretty big and they’re huge in Norway. They’re about to change their name and get oil out of the name.

CURWOOD: Yeah, what are they going to call themselves?

DYKSTRA: The new name is Equinor. It’s one of those names you can’t quite figure out. Turns out the Nor at the end stands for Norway. The Equi, we’re not, I can’t figure out what that stands for.

CURWOOD: It could stand for Equity, Peter, because they put all that oil wealth from Statoil I think from some time in the mid 90s into the sovereign wealth fund of Norway, which is now worth over a trillion dollars. In fact, I think it’s the biggest or nearly the biggest sovereign wealth funds in the world. So what’s going on with them?

Statoil’s branding has evolved over the past few years, from the pre-2009 blue-and-gold logo, to a pink logo, to its new name of Equinor. (Images: Wikimedia Commons)

DYKSTRA: Well, I’d love to get me a piece of the trillion dollars but Equinor is still going to stay in the oil business, but they want to make sure that their new name and their new branding reflects the fact that they’re not just an oil company. That they are into clean energy, natural gas and a whole lot of other things.

CURWOOD: Maybe electricity, I think half the cars there are electric. Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: We are going to talk about a positive story that sounds new but it’s actually something that has its roots in the 19th century. There are cherry orchards in Northern Michigan that instead of using more pesticides are using a small falcon, the American kestrel, to protect the crop and make sure that other birds that are picking cherries off the cherry tree don’t get to do their work and have their meals.

CURWOOD: So, in other words, the falcons are eating those other birds?

DYKSTRA: They are, and it happens in other areas of the world too. In New Zealand there’s another species of falcon that’s used to protect crops. In some farms they are using owls to pick off rodents to protect crops. Even bluebirds to pick off insects and make sure that less pesticides are used in certain areas.

CURWOOD: So, how long has this been going on?

Rachel Carson’s seminal book, Silent Spring, was in part inspired by a Supreme Court case in which a group from Long Island sued the makers of DDT. (Photo: USFWS, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, you know what, back in the 19th century the United States Department of Agriculture in the 1880s had a Unit of Economic Ornithology. That’s what it sounds like – birds for money. And that group studied how to use birds and possibly other animals to protect crops. They lasted until the 1940s and the reason they went out of business and there was no more Unit of Economic Ornithology was that wonder chemicals like the pesticide DDT came along and we know what happened there.

CURWOOD: Uh oh, hey uh, what do you have for us from the history vaults this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, we are going to stick with DDT. March 28, 1960 the Supreme Court heard and appeal on a case brought by Long Islanders about DDT spraying to eliminate gypsy moths. The court threw the case out in spite of the fact that plaintiffs brought evidence that cow’s milk was contaminated with DDT residue, that the drift from DDT spraying was going into communities and potentially harming humans, that it was clearly harming birds.

CURWOOD: And what was the vote on the Supreme Court?

DYKSTRA: The dissenter, who wrote a dissenting opinion and cited all these things was somebody that we talked about recently, the closest thing to a tree hugging justice on the Supreme court we’ve ever had, William O. Douglas. Somebody else who followed the case closely and turned it into one of the greatest environmental books of all time was Rachel Carson. She used the evidence from the case and her own research as a government scientist, and two years later published the book Silent Spring, which eventually was the key to getting DDT banned in the United States two years later in 1972.

CURWOOD: Yes, thank you Rachel. And thank you Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN dot org and daily climate dot org. We’ll talk to again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Ok, Steve. Thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE dot org.

Related links:

- Reuters: “Statoil to rebrand as Equinor in green energy push”

- Environmental Health News: “Protecting crops with predators instead of poisons”

- Read Justice William O. Douglas’s dissent in the Long Island DDT spraying case

- Environmental Health News

- The Daily Climate

[MUSIC: Simon & Garfunkel, “El Condor Pasa” on Bridge Over Troubled Water, Traditional Peruvian/arr.Daniel Alomia Robles/arr.Jorge Milchberg/lyrics Paul Simon, Columbia Records]

A Waddle of Penguins

On land, a group of penguins is called a “waddle”; a group of penguins in the water is a “raft." (Photo: David Cook, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

[SOUNDS OF JACKASS PENGUINS AT AQUARIUM]

CURWOOD: These Jackass penguins live at the New England Aquarium -- where Living on Earth’s Savannah Christiansen and Aynsley O’Neill took a penguin field trip and found Little Blues –

[CALLS OF LITTLE BLUE PENGUINS]

CURWOOD: and RockHoppers –

[CALLS OF ROCKHOPPER PENGUINS]

CURWOOD: and lots of penguin fans.

CHRISTIANSEN: Are you guys fans of penguins?

DILLON: Yea.

CHRISTIANSEN: Why? Why do you like penguins?

ALEX: They’re cute, I don’t know -- they’re entertaining.

CHRISTIANSEN: What if we told you that they just discovered a super colony of 1.5 million penguins that they didn’t know existed before, what would you guys say to that?

ALEX: I would want to go and see them.

CHRISTIANSEN: Why do you like penguins?

ELLIE: Cause they’re soft! Because this one’s soft.

MOM: That one’s soft? Do you like to watch them swim fast?

ELLIE: Yes swim fast!

MOM: Hey Daniel, why do you like penguins?

DANIEL: Cause I just do!

MOM: You just do?

DANIEL: I like to feed penguins.

MOM: Oh you like to feed them?

An Adélie penguin, easily identifiable with its simple black-and-white coat and button eyes. (Photo: oliver.dodd, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CHRISTIANSEN: What would you feed them if you could?

DANIEL: Fish! Yum yum yum.

CHRISTIANSEN: Why do you like penguins?

ISABELLA: Because they’re wicked cute and they’re my best friends favorite animal.

MICHAELA: Because they’re fun to look at, how they, like, swim and do funny stuff and talk to each other.

JACKSON: Cause they’re so cute.

CHRISTIANSEN: If you guys could have a penguin would you own a penguin as a pet?

ALL: Yea!

CHRISTIANSEN: What would you do with your penguin?

ISABELLA: I would put it in my pool.

MICHAEL: I would bring it to the beach.

JACKSON: I will bring mine to a beach too.

CURWOOD: Well, as much as people like them, several species of penguins are now listed as endangered or vulnerable. So the recent discovery of a super-colony of some one and a half million Adélie penguins in Antarctica is great news, especially for scientists who study these birds that fly through water. And none is happier than University of Washington conservation biologist Dee Boersma. Welcome to Living on Earth, Dee!

BOERSMA: Well, thanks very much. It's nice to be on.

CURWOOD: So, tell me about the Adélie penguins. What are they like?

BOERSMA: The Adélie penguin is the perfect penguin. People see it on public television. They're the black and white ones, and they look like they have button eyes, and of course, they're so well feathered because they live in Antarctica, so they have feathers that go down to the opening of their bill where they can breathe, and they're beautiful black and white, and not very tall. They're just about the size of a good stuffed penguin toy, so they're about a little over a foot high, and they were actually named Adélie penguins by a French explorer. His wife was named Adelie or Adélie, and so that's how the penguins got their name. So, he must have been in the Antarctic a long time really missing his wife.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I guess so! By the way, where are penguins evolutionarily speaking?

BOERSMA: Oh, they're old. They're from like the Miocene, you know, like 200 million years ago. So, they used to have penguins that are now extinct that were as big as people, so some of them weighed like 200 pounds and they got to be five foot four, but now the biggest penguin we have is the Emperor penguin and that's the one that's featured in the film "March of the Penguins."

Jackass penguins at the New England Aquarium gather around during feeding time. (Photo: Aynsley O’Neill)

CURWOOD: So, what exactly is a super colony?

BOERSMA: It's a lot of penguins. Most of the time, I mean, penguins are colonial, but usually they live in fairly small colonies depending on the species and sometimes they –they may not even live very close to each other. But Adélie penguins, they live very close together and they make their little nest out of rocks that they collect and deposit. So, a super colony means you got a whole heck of a lot of Adélie penguins. Most of the colonies might have a few thousand penguins, but a million penguins, well, that's a really big colony.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Now, how did researchers come to find these penguins, this huge population?

BOERSMA: Well, it is incredible to find 1.5 million penguins that you didn't know about, but that's really the wonders of technology. Technology is allowing us to see things that we couldn't see before, and in fact, Heather Lynch found double the population size of Emperor penguins by using, again, this satellite imagery. And of course, satellites, they provide us our weather and in this case they're providing a satellite data so that we can find these new colonies of penguins, and if you look at the satellites you can see where the penguins are because they eat a lot of krill which are just shrimp, and so when they poop, it poops pink, and if there's a big colony of penguins you see a lot of pink poop. And then you have to go on the ground and find these places, and then you can see the penguin. But that's the wonders of the technology because you can do it from space.

CURWOOD: Now, how common are discoveries like these?

BOERSMA: Well, really rare. I mean, it's just because of the change in technology.

African penguins, also known as jackass penguins, at the New England Aquarium. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about where these Adélies were found. What kind of territory is it?

BOERSMA: Well, it's well named ... in the Danger Islands, [LAUGHS] so you wouldn't want to go there as it's dangerous. So, that's where they found it.

CURWOOD: Now, the Danger Islands what kind of protected status does this area have now that we know about this penguin super colony?

BOERSMA: Well, most of these areas don't really have very much protection. There is a new marine protected area in the Antarctic. The Antarctic, of course, is protected by the Antarctic Treaty, of which the United States is a signatory, and so are many other countries. That's why we have all these bases in the Antarctic.

CURWOOD: So, as I understand it then, these Danger Islands are, well, they're not protected. People could go, kind of do what they want to do.

BOERSMA: You could, but good luck. I mean the Danger Islands are well named, so there's all kinds of rocks and things there, and there's ice. So, you would have a heck of a time.

CURWOOD: Now, talk to me about the Emperor penguin discovery. Where and just how many there?

BOERSMA: They doubled the number of colonies of Emperor penguins known. So, that's the thing. When you find 1.5 million penguins or double the number of colonies known for a species, it certainly changes your view. But it probably doesn't change the trend because, of course, we're interested in trends and what's happening to penguins, and when you find a lot more when you think that they're really rare then that's really good news because then you know that they're not in as much trouble as you thought before. I mean, suddenly there's more penguins than we thought for some of these species, so that's good news, but it doesn't mean that the trends have changed, it has just bought us more time. So, we hope that some of these species of penguins don't continue to decline.

CURWOOD: Now, what does all this mean for the conservation of penguins?

BOERSMA: Well, it means that we're in better shape. I mean, of course, the Adélie penguins, they are considered of least concern because there are so many of them, but the nice thing is a few years ago they were considered near threatened. But now that we’ve found these new colonies, now we say they're at least concerned because there's you know million more Adélie penguins than we thought before, so that's the good news.

Mating Adélie penguins at Cape Adare in Ross Sea, Antarctica. The supercolony on the Danger Islands has over 750,000 breeding pairs. (Photo: Brocken Inaglory, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Professor Boersma, what can be done to ensure the global survival of penguins?

BOERSMA: Well, there's a lot of things that individuals can do. Part of it is your food choices. If you're going to eat anchovies on your pizza, great, eat anchovies on your pizza, but don't eat farm-raised chicken that are fed anchovies, or farm-raised salmon that are fed anchovies. All of those things take food away from penguins.

The other thing we can do is make marine protected areas, so that there are some places where the fish are protected so that the penguins can thrive and the fish can reproduce in there and then they can go out from these marine protected areas and reproduce in other places, but we need to have reserves to be able to protect fish, penguins and other species.

CURWOOD: By the way, why are you so fascinated with penguins?

BOERSMA: Well, it's hard to find people that aren't. They walk upright, they're curious, they're cute, they're industrious. I just don't think there's anything not to like about penguins unless you're trying to grab ’em, and then they bite you and then there's a good reason not to like them, but of course, they don't want to be grabbed.

CURWOOD: And I know you are a scientist, but come on, you can tell us your favorite.

BOERSMA: Well, you know, that's really hard. I've spent 45 years of my life working on Galapagos penguins and now I just finished season 35 working on Magellanic penguins in Argentina. So, I really like penguins, but what's more important to me are really long-term studies because long-term studies really inform us about our world and what other creatures are facing as well as humans.

CURWOOD: When did you first meet a penguin?

BOERSMA: Ahh Jeez. A long time ago. I guess it would be 1970.

CURWOOD: And what did you think?

BOERSMA: I thought that was one of the most interesting coolest things I had ever seen. I met a Galapagos penguin and I thought, gee, “What's a penguin doing living on the equator?” I thought it was just crazy. They've never seen an ice flow in their life, but I just I found penguins fascinating and clearly, after 45 or so years I still find them awfully interesting.

Professor P. Dee Boersma, with Magellanic penguins at Punta Tombo in Argentina. (Photo: P. Dee Boersma, University of Washington)

CURWOOD: I spent some time around Cape Town and the so-called Jackass penguins there.

BOERSMA: And you know why they're called Jackass? They're call Jackass because the first explorers were camping out and they thought they were surrounded at night by donkeys and when they got up in the morning there were no donkeys. There were just penguins, and hence the name Jackass penguins.

[SOUNDS OF JACKASS PENGUINS]

CURWOOD: Because they make that noise, that braying noise.

BOERSMA: Yeah.

CURWOOD: They're very smart though, those penguins.

BOERSMA: Right. Now penguins are not dumb, they would've gotten this far if they were. They know how to get along in our world to some extent. We just got to give him a little space, so they can.

CURWOOD: But what is their secret to always having the tuxedo completely neatly pressed?

BOERSMA: Well it's not. If you look in Antarctica or even at Boulders Beach where you were in South Africa, many of them look pretty muddy depending on the day and stuff and they can be covered in poop. And so, their secret is they go to sea and wash off and then when they come back they look like they just came from the dry cleaners. They're really well dressed and well pressed.

CURWOOD: Penguin expert Dee Boersma teaches at the University of Washington. Thanks so much for taking the time today, professor.

BOERSMA: It is my pleasure. It's always great to talk about penguins. I hope everybody helps save one.

Related links:

- The study that estimated the number of Adelie penguins in the Danger Islands supercolony, published in Nature

- The Center for Ecosystem Sentinels was founded by Professor Boersma

- Special thanks to the New England Aquarium for their penguin calls and visitor testimonies

- See Professor Boersma’s TED Talk on penguins here

[MUSIC: Gary Burton, et al, “Prelude for Vibes” on Next Generation, by Vadim Neselovsky, Concord Records]

Stealing Dirt: A Thieving Penguin

The Gentoo penguin stealing dirt. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: We head north of Antarctica now, for a different penguin in a different land. Gentoo penguins can be found in the Falkland Islands, but it’s a comparatively sparse population, especially early in the breeding season. At a colony on Carcass Island, writer Mark Seth Lender discovered that a penguin’s sense of how much space is enough – and how close is too close – can be unpredictable, even to other penguins.

Stealing Dirt

Carcass Island, West Falklands

© 2015 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

[SOUNDS OF GENTOO PENGUINS]

LENDER: Gentoo Penguin is building his nest from the only thing at hand: Dirt. In chunks. By the beakful. Brown clingy stuff that plasters neatly to the purpose he has in mind. He bends to pick, then carry, then drop at Her penguin feet. And She accepts every small measure. Like a treasure. With bright orange bill she then mills and turns the shape that rises like a hand-built pot. Round and round. Well-contrived. Perfect for their well-laid plans, the seat, the center of things that are to come.

The offender gets bitten (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Known only to his penguin-self, Gentoo Penguin finds the ground over there more, and better, than the ground over here; and makes his shuffling rounds.

He’s getting away with it. No one tries to stop him. In the Southern Hemisphere it is early days of spring. The clans that make this colony are thin, and widely spaced and at the place he’s stealing from, no one’s home. And Gentoo’s left alone.

Crossing from where the mud is always muddier to his own turf (where there is no turf but only mud), Gentoo makes a wrong turn And every penguin in his very-own penguin’hood tells him, “Penguin, get gone!”

[QUARRELSOME PENGUIN CALLS]

He jumps, from one, to collide, with another. They howl they peck they bat him with the flat of their muscular arms that once were wings. He leaps, he spins! And every penguin person wants a piece of him.

Gentoo penguins building their nest (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Safe, at last, his reward for all the dirty work he’s done is love. Paired in perfect synchrony, two Gentoo penguins rise and pointing toward the sky they sing.

[MORE PENGUIN CALLS]

Bending low they bow, then high, then side to side. And like the mariner he is, (most of his life spent at sea) he plies her broad ship’s keel of a back. She cranes her neck, they clasp, then grasp each other beak-to-beak. And in this ancient perfect circle of a pose they hold. And hold. And hold.

[MORE PENGUIN CALLS]

CURWOOD: That’s writer Mark Seth Lender – to check out his photographs of Gentoo penguins in love and war, waddle over to loe dot org.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s personal website

- Read more about Gentoo Penguins at NatGeo

[MUSIC: Gary Burton, et al, “Prelude for Vibes” on Next Generation, by Vadim Neselovsky, Concord Records]

CURWOOD: Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Hannah Loss, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Aynsley O’Neill, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

Thanks to One Ocean Expeditions.

Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org – and like us, please, on our Facebook page – PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth