November 24, 2017

Air Date: November 24, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

New Route for Keystone XL

/ Jaime KaiserView the page for this story

One of President Trump’s first actions was to reverse his predecessor’s rejection of the Keystone XL pipeline project to carry carbon-heavy tar-sands crude from Canada to Texas. The final official step to realizing the project was a Nebraska Commission’s approval of the pipeline route, which it’s now given. But the route is not the one the company preferred. As Living on Earth’s Jaime Kaiser explains, this gives pipeline opponents hope and possible cause to continue their fight, and may help put the economic feasibility of the project in jeopardy. (05:51)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week in Beyond the Headlines, Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood discuss the rapid rise in people registering for federal disaster aid after this year’s record-breaking hurricanes, wild fires and floods. Then they note how the Pope regards climate denial, and remember an infamous environmental computer hack. (03:38)

Meat from Plants

/ Noble Ingram, Savannah ChristiansenView the page for this story

The offerings of meat substitutes for vegetarians and vegans have leapt forward in recent years but for most meat-eaters, nothing quite measures up to the real thing. That’s what companies like Impossible Foods are trying to change. Using a complex combination of plant proteins, along with a key genetically-engineered ingredient, the company has a plant-based burger intended to appeal to carnivores. Living on Earth’s Savannah Christiansen and Noble Ingram join a crowd of hungry students in Cambridge, Massachusetts to sample the burger, for a taste test. (05:20)

Meat 2.0

View the page for this story

The Silicon Valley-based company Impossible Foods is aiming primarily at carnivores with its Impossible Burger, genetically engineered from plant protein to look and taste as much as possible like red meat. It’s already available in some restaurants. Fordham University Professor Garrett Broad joins host Steve Curwood to examine plant-based meat’s culinary and regulatory future. (08:04)

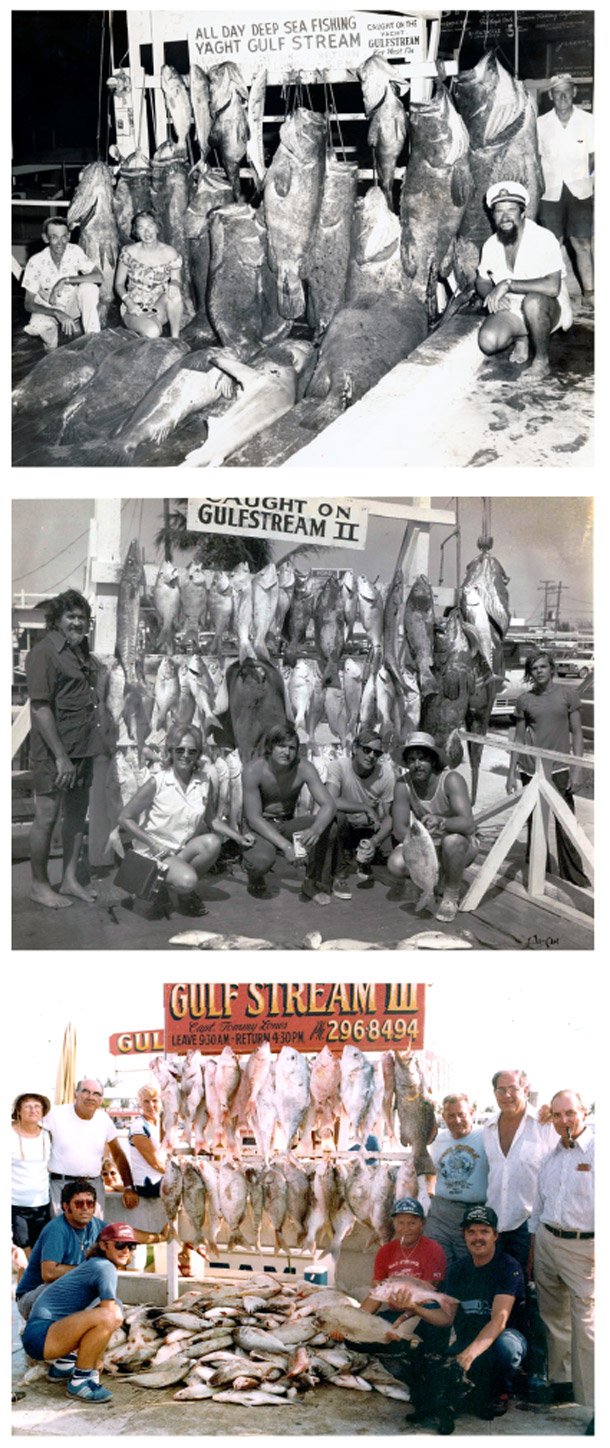

American Seafood: Heritage, Culture & Cookery from Sea to Shining Sea

View the page for this story

Barton Seaver is a chef with a mission: to rekindle America’s taste for abundant seafood. His new book catalogues more than 500 species of seafood interspersed with recipes, photographs, and an extensive history of America’s relationship with food from the sea. Host Steve Curwood joins Seaver at a dockside fish market in Portland, Maine to scope out the freshest, most sustainable fish and shellfish – and then, they shuck oysters and cook up some tasty, fishery-friendly mackerel in his kitchen. (23:28)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Garrett Broad, Barton Seaver

REPORTERS: Jaime Kaiser, Peter Dykstra, Savannah Christiansen, Noble Ingram

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The Keystone XL pipeline wins approval in Nebraska, but with an alternate route that gives opponents the chance to continue their struggle.

KLEEB: While I deeply appreciate the fact that TransCanada did not get their preferred route, it also opened up a huge victory for us in order to fight this now on the federal level.

[CHEERS]

CURWOOD: And TransCanada may not think it makes economic sense. Also, how to make sure you’re buying sustainable seafood. Just ask.

SEAVER: What's the catch of the day? Well, hey, today, ocean perch. It is abundant right now. The fisheries are just killin' it, bringing it in day after day. This fish was just landed yesterday morning. Beautiful fish. Today we've got it for $3.99 a pound. Wow! What a great deal.

CURWOOD: Celebrity chef Barton Seaver and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country”, Warp Records 2000]

[THEME]

New Route for Keystone XL

Bold Nebraska Founder Jane Kleeb rallies at the NYC People’s Climate March in 2014. (Photo: Joe Brusky, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The long delayed Keystone XL pipeline project has cleared one of its final hurdles, thanks to the Nebraska Public Service Commission. Concerns over global warming ignited years of conflict over this proposal to pipe carbon-heavy crude over a thousand miles from the tar sands of Canada to a junction in southern Nebraska. And from there a pipeline to refineries in Texas has already been finished.

Environmental activists and landowners have fought against Keystone XL for years, and the recent regulatory ruling in Nebraska has both sides claiming victory. Living on Earth’s Jaime Kaiser has our story.

KAISER: In a 3 to 2 vote, the Nebraska Public Service Commission did approve Keystone XL, but not the route pipeline company TransCanada preferred. Instead, they’ve signed off on the “Mainline Alternative Route,” as they’re calling it, which would take a detour that avoids some the more vulnerable areas of the Ogallala Aquifer and the Nebraska Sandhills. Some of commissioners offered written statements defending their position, but only Commissioner Chrystal Rhoades spoke at the meeting itself.

RHOADES: The applicant provided insufficient evidence to substantiate any positive economic impact for Nebraska from this project. There was no evidence provided that any of the jobs created by the construction of this project would be given to Nebraska residents.

KAISER: Their decision came just days after 210,000 gallons of crude oil spilled from the original Keystone Pipeline, also owned by TransCanada. The Keystone XL fight is nothing new. There’s been fierce controversy over its construction since the project was proposed in 2008, especially regarding the environmental impact of the Canadian tar sands oil it would carry. When former President Obama rejected TransCanada’s request to build on US soil in 2015, it seemed like the project had been shuttered once and for all. So environmental activists were horrified when President Donald Trump seemed to bring it back from the dead with the stroke of a pen.

The first phase of the Keystone Pipeline system recently leaked over 210,000 gallons of crude oil in South Dakota – a state that neighbors Nebraska. (Photo: shannonpatrick17, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

TRUMP: Today I’m pleased to announce the official approval of the presidential permit for the Keystone XL pipeline.

KAISER: He cited its potential economic benefits.

TRUMP: When completed, the Keystone XL pipeline will span 900 miles. Wow. And have the capacity to deliver more than 800,000 barrels of oil per day to the gulf coast oil refinery. That’s some big pipeline. The fact is this that this 8 billion dollar investment in American energy was delayed for so long, it demonstrates how our government has too often failed its citizens and companies over the past long period of time.

KAISER: But in Nebraska, a coalition of farmers, Native Americans, and activists say, even a permit from the president himself doesn’t guarantee the project will pass through their state.

KLEEB: This decision today throws the entire project into a huge legal question mark.

KAISER: That’s Jane Kleeb, the founder of Bold Nebraska, a social action group committed to halting construction of the pipeline. She explained at a post-decision rally that there are avenues for appeal.

KLEEB: The pipeline route that is now on the table in the state of Nebraska has never been reviewed by the feds. And so while I deeply appreciate the fact that TransCanada did not get their preferred route, it also opened up a huge victory for us in order to fight this now on the federal level.

[CHEERS]

KAISER: Even among pipeline opponents, emotions were mixed. The decision keeps some landowners out of the pipeline’s path, but not all of them.

TANDERUP: My name is Art Tanderup. Helen and I are landowners on the route. We’re disappointed today. Sorry, um, you know, we’ve got this foreign corporation coming in and stealing our land. We know it’s not over. We’re going to fight until the end, but how can our government give a foreign corporation the right to come in and take land from their citizens.

KAISER: Ponca Tribal Chairman Larry Wright, Jr. also spoke at the rally, where he drew parallels to another pipeline controversy.

WRIGHT: A year ago, water protectors were in Standing Rock being shot with water cannons, being gassed. Unarmed people were being attacked.

KAISER: Of course, he’s referring to the stand-off in North Dakota over the Dakota Access Pipeline, which is not a TransCanada project. But then he turned his attention to the recent Keystone Pipeline spill in South Dakota.

WRIGHT: And here, almost a year to the day later, we have a 210,000 gallon spill along the first route. That’s what could happen right here.

The Sandhills of Nebraska is a mixed-grass prairie ecosystem that sits atop the Ogallala Aquifer, and is a key stopover for the Great Sandhill Crane Migration. (Photo: Ken Lund, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

KAISER: The Nebraska Commission didn’t account for that spill, or any spill. According to state law, they weren’t allowed to even consider safety concerns. Apparently, they were only meant to consider whether the pipeline was in the state’s public interest. But Rod Johnson, one of the commissioners who approved the project, addressed safety in his written defense anyway.

He wrote, “Safety was the number one issue raised at the Commission's four public meetings and in the many thousands of written comments we received during this process. TransCanada and project advocates have often said that the Keystone XL pipeline will be the safest in history. Nebraskans are counting on that promise, too.”

TransCanada President Russ Girling said, “We will conduct a careful review of the Public Service Commission's ruling while assessing how the decision would impact the cost and schedule of the project.” The Company is expected to decide before the year is out whether they’ll move forward with Keystone XL, or not.

For Living on Earth, I’m Jaime Kaiser.

Related links:

- Omaha World-Herald: ”Controversial Keystone XL Pipeline Route Across Nebraska Is Approved, But Hurdles Likely Remain”

- The Washington Post: “Keystone pipeline spills 210,000 gallons of oil on eve of permitting decision for TransCanada”

- Nebraska Public Service Commission

- Bold Nebraska Keystone XL Press Release

- TransCanada Keystone XL Page

- Our recent conversation with Bold Nebraska’s Jane Kleeb

[MUSIC: Gary Burton/Chick Corea, “Native Sense” on Native Sense, composed by Chick Corea, Concord Records]

Beyond The Headlines

The wildfires that ripped through California neighborhoods in October 2017 and left them destroyed were just one of many natural disasters this year that spurred nearly one and a half percent of the U.S. population to register for Federal disaster aid. (Photo: California National Guard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Off to Atlanta, Georgia now to check in with Peter Dykstra and what stories beyond the headlines caught his fancy. Peter’s with Environmental Health News. That’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org, and he’s on the line now. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve.

Here’s a notable statistic for you. The number of Americans filing for Federal disaster aid increased by nearly a factor of ten this year. Four point seven million Americans - one and a half percent of the US population - registered with FEMA so far in 2017 in a year of tragedies, including three major hurricanes, huge wildfires in California and elsewhere, massive flooding, and more.

CURWOOD: Wow, that's the headcount, but what about the money total?

DYKSTRA: Well, they haven't tallied that up yet, but it's sure to be well up into the tens of billions. And that's not counting the thousands of extra hires FEMA has brought on to process claims and help fix the damage done. FEMA’s also dealing with fighting fraudulent claims and hackers diverting some legitimate disaster payouts.

CURWOOD: So how big a problem is that?

DYKSTRA: I haven’t seen any data, but I guess it happens every time there’s a lot of government cash available.

November 16, 2017 Pope Francis sent a message to COP23, the UN climate talks in Bonn, calling climate change denial “corrupt.” (Photo: Tânia Rêgo, Agência Brasil, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0 br)

CURWOOD: I guess. And with that, time now to switch topics.

DYKSTRA: Ok, Steve. You want to know what the head of the Catholic Church thinks is "corrupt"?

CURWOOD: Try me.

DYKSTRA: It’s climate denial. Last week Pope Francis sent a message to the UN climate talks in Bonn. The Pontiff called climate change, “one of the worst phenomena that our humanity is witnessing.” He denounced what he called four "perverse attitudes" on climate. "Negation, indifference, resignation, and trust in inadequate solutions."

CURWOOD: Now didn't a band of deniers stage a pilgrimage to the Vatican to "educate" the Pope a couple of years ago?

DYKSTRA: They did, when the Papal Encyclical on the environment came out in 2015.

CURWOOD: Oh, yeah, his call on humanity to protect and be good stewards of Earth called “Laudato Si.” I take it that the Pope didn't grant them an audience, though.

DYKSTRA: Yeah not only that, their press conference didn't even draw an audience either, and they kind of came off looking like un-wise men bearing grifts.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Hey what piece of environmental history do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: We mentioned computer hacks earlier, so let's talk about the most infamous environmental computer hack in history.

CURWOOD: I'm guessing that would be the theft of thousands of climate scientists' emails that subsequently acquired the nickname “Climate-gate.”

DYKSTRA: Right you are. This week in 2009, it was revealed that about 10,000 emails between climatologists at the University of East Anglia and their colleagues around the world had been stolen. Those emails conveniently found their way into the hands of groups opposed to taking action on climate, who highlighted a few poorly-worded and dumbly-expressed exchanges between the scientists to spin the whole calculation on rising global temperatures as a giant hoax.

CURWOOD: And I recall that, even more conveniently, this all came out just on the eve of a major climate summit in Copenhagen.

DYKSTRA: Yes, and it worked out much better for climate deniers than did their pilgrimage to Rome years later. Multiple investigations cleared the climate scientists.

After the computer hack of thousands of climate scientists’ emails in 2009, climate scientist Michael Mann wrote a book on the event called The Hockey Stick and Climate Wars. (Photo: NASA/Dave Bowman)

CURWOOD: Yeah, one of them, Michael Mann, wrote a powerful book called “The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars”. That book explained the whole evidence in detail.

DYKSTRA: That’s right, and then police investigations pointed inconclusively to Russian hackers, but you know, Steve, the notion that climate scientists were fraudsters hell-bent on money and power was cemented among those who desperately wanted to believe just that. It’s still there and they still trot the fiction out.

CURWOOD: Hmm, Russian hackers. What a concept.

DYKSTRA: Yeah.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra’s an editor with EHN.org, that’s Environmental Health News and Daily Climate.org. Thanks, Peter, we’ll talk soon.

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you next time.

Related links:

- The Washington Post: “Federal aid claims jump tenfold in 2017, after series of record-breaking natural disasters”

- Reuters: “Climate change denial or indifference are ‘perverse attitudes’: pope”

- The Guardian’s hacked climate science emails coverage

[MUSIC: David Chevan/Warren Byrd, “Let Us Break Bread Together” on Let Us Break Bread Together, traditional African-American, Reckless DC Music]

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org. Coming up, a meaty burger made from plants. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Chevan/Warren Byrd, “Let Us Break Bread Together” on Let Us Break Bread Together, traditional African-American, Reckless DC Music]

Meat from Plants

The Impossible burger’s combination of plant proteins lends it an uncanny meat-like texture, as well as flavor. (Photo: Noble Ingram)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The human species evolved as omnivores, gathering leaves, fruits, nuts and berries, and occasionally hunting down creatures for their flesh. And while many vegetarians have lost the taste for meat, whole fast food empires have been built on the flavor appeal of the hamburger. But beef is hard on everything from the arteries to the environment, so now hi-tech food designers have come up with the next generation of cholesterol-free burgers that don’t send cattle to the slaughterhouse.

One of these newish offerings is a plant-based patty being marketed as “the impossible burger”, because thanks to a bit of genetic engineering it so closely mimics ground beef, that it actually “bleeds”, like the real thing. The other day Impossible Foods offered free samples near Harvard Square, and Living on Earth’s Savannah Christiansen and Noble Ingram headed over for a taste test.

[CROWD SOUNDS]

INGRAM: So, Savannah and I, we’re standing in this parking lot pretty close to Harvard. It’s raining, and there’s this big crowd of students. Everyone’s waiting outside of this black food truck.

CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah, and every once in a while this tray full of small burgers comes out of the truck.

INGRAM: You know, those burgers are actually Impossible Burgers. They look, they smell like meat, but they’re entirely plant-based. And from the looks of it, they’re drawing a pretty big crowd.

Despite the rain, a crowd gathers in Cambridge for a chance to try the Impossible Burger. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

CHRISTIANSEN: Granted, it is free food, and they are students. But I do have to say, I’m a little apprehensive about trying this burger. I mean, I haven’t eaten red meat in about eight years or so, and the idea of my veggie burger bleeding while I’m eating it just sounds really unappealing.

INGRAM: [LAUGHS] You know, I also gave up eating meat, a little more recently. But I have to say, I’m pretty excited about this.

[CROWD SOUNDS]

CHRISTIANSEN: All right, so Noble has just received his Impossible Burger.

INGRAM: I mean look at that, it's brown! It’s sort of sizzly on the bottom. It's good. I mean it's sort of heavy like meat. Dense, chewy, kind of oily.

CHRISTIANSEN: It smells like barbeque, I would say. It smells good. I’m not going to lie. Ok here we go. Wow, yeah, tastes like how I remember meat tasting. I don’t know that I would guess that it’s plant. But I’m going to let you eat the rest of this [LAUGHS].

[CROWD SOUNDS]

CHRISTIANSEN: So, every time this tray comes out, hungry students reach out to grab them and the tray empties in no time at all.

MONCADA: I’m actually a pretty big meat eater. I tried to be pescatarian for a while, and that didn’t really work because I missed the flavor of meat.

LEE: I’m a hardcore meat eater, but I would be open to not doing so if the taste was similar.

KUPFERMAN: I’m sort of in the process of becoming vegetarian so this is very exciting.

Producer Noble Ingram tries the Impossible Burger. Only recently off of red meat, he was eager to taste an alternative. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

INGRAM: And you know, asking around, people’s reasons for showing up are really striking. It can be anything from the political to the personal.

LEE: I know farming meat causes a lot of methane emissions. It’s really, from what I hear, terrible for the environment so I’d definitely be willing to switch over to plant-based meat.

MOBASHIR: I’m Muslim and so I have to try to eat halal. But I break every once in a while, so if I have another alternative, why not?

BRANDE: For me, I have a lot of friends who are vegetarian or vegan, and sometimes it’s hard to go out to eat or cook at home. So, it would be cool if there was something that was like a bridge between that.

CHRISTIANSEN: And you know many of the people, that I talked to say that they have environmental reasons for trying this burger, and that makes sense. The company says their goal is to reduce the carbon cost of producing meat. According to their website, they say their burger uses only a twentieth of the land, a quarter of the water, and produces just an eight of the greenhouses gases that a normal beef patty would.

INGRAM: And on top of that, people think these burgers taste good too.

KUPFERMAN: It sort of tastes like a cross between real red meat and seitan. It’s definitely more, like, meaty than seitan. It has more of that flavor. But I kind of like it better than red meat.

HENSON: So, I’m from Tucson so we eat a lot of Mexican foot, and there’s a similar spice taste to the sort of Sonoran-inspired meats that we make.

Producer Savannah Christiansen poses next to the Impossible Foods truck. As a long-time vegetarian, she appreciated the burger’s appeal, but wasn’t keen on taking a second bite. (Photo: Noble Ingram)

CHRISTIANSEN: So, I was reading that to make a veggie burger taste beefy and appear to bleed, the company extracts a protein called heme, which is found in blood, but also in plants. And in this case, they get the heme from soy and use genetic engineering to insert it into yeast and then cultivate it in these massive tanks. So that makes the burger genetically modified.

INGRAM: You know, sounds like this burger’s got a complicated genetic background. And that’s an important question to ask for anyone concerned about biological tampering with their food.

MONCADA: I'm a biology person and I feel like there is a lot of mislabeling of GMOs, and that is a personal pet peeve of mine. So, I’m less concerned about that, and more concerned about just the quality of the ingredients in general, regardless of it they are genetically modified or not.

INGRAM: Alright, Savannah, what’s the verdict?

CHRISTIANSEN: Well, personally I don’t know if I would eat it again, but it does seem to be pretty popular.

INGRAM: Yeah, I didn’t think it was quite beef-like but I would definitely have it again.

CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah, well you can get it in some restaurants already, for about the same price as a regular burger.

INGRAM: And I hear this is part of the New England roll out tour. They’re trying to figure out if there’s demand out here.

CHRISTIANSEN: Well, based on what we saw today, I think there could be.

Related links:

- Impossible Foods

- Impossible Foods’ New England Debut

Meat 2.0

The Impossible Burger is currently available at a few select restaurants around the country. According to Broad, the company is working on a retail plan. (Photo: SharonaGott, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: The Impossible Burger is just one of many engineered meat alternatives that are becoming increasingly familiar, and a tide of new biotech companies sees new opportunities in the food industry. But despite support from investors like Bill Gates, they have a long way to go before they’re a staple of every kitchen. The key to mainstream success, says food activist and Fordham University Communications professor, Garrett Broad, will be transparency about the ingredients.

Professor Broad joins us now from New York City. Welcome to Living on Earth.

BROAD: Thanks so much for having me. Glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So, you can tell me, Garrett. Have you tried the Impossible Burger, and if you did what did you think?

BROAD: I have tried the Impossible Burger. I had it here in New York City at one of the Bare burger franchises, and you know as someone who hasn't eaten meat for about a decade or more, it was an interesting experience for me. I enjoyed it definitely, but I don't think I'm the ideal person to tell you whether it tasted like meat or not ‘cause t's been a long time for me.

CURWOOD: I kind of get the impression that this burger is maybe more for people who are making the transition from eating meat to a more vegetable-based diet, and it gives a chance to have the flavor. What's your thought?

BROAD: Yeah, that really is key to the strategy of companies like Impossible Foods as well as others in this sector. Vegetarians are not their primary market. In fact, in a lot of ways they don't want their products to be associated with vegetarians at all. They're really aiming for those meat reducers. They're aiming for those folks who are maybe looking to switch out a meat option once, twice, three times a week. They want this to be a product that is meat. It's just meat from plants.

CURWOOD: So, Garrett, right now the Impossible Burger couldn't be sold in certain European countries because it contains genetically modified ingredients. Just what is the genetic modification involved in the Impossible Food burger?

BROAD: So, Impossible Foods uses a genetic modification in the construction of heme. Heme is found widely in both the animal and plant kingdom, and it is an ingredient that gives certain flavor and smell and texture to meat as we know it, but it's also in a variety of plant based sources, and in fact, the Impossible Foods is getting this from a plant based source.

Impossible Foods' founder Pat Brown has stated that he views cattle as an inefficient mechanism for producing meat. As Prof. Broad explains, many companies selling plant-based alternatives market their products as meat, just not meat that comes from animals. (Photo: InterContinental Hong Kong, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

And in the US we have a much longer history of accepting genetically modified foods into our food system. Europe is a different story and they have been much more strict in terms of the treatment of genetically modified ingredients and genetically modified foods in general.

CURWOOD: Now, the Food and Drug Administration, the FDA, has opted not to certify the key plant protein in the Impossible Burger as GRAS, as Generally Recognized As Safe. Tell me, what does that mean and how important is that distinction, do you think?

BROAD: So, the FDA situation with impossible Foods is a little complicated. They haven't said that the hemoglobin ingredient is not safe, but what they have said is that it has not passed their Generally Recognized As Safe requirement as yet. They're looking for more testing from the manufacturer, from Impossible Foods, to meet this, what's called GRAS, requirement. So, when people often hear, “Oh, FDA says this is not Generally Recognized As Safe,” they’re a lot of times thinking, “Oh this must mean they're saying it's unsafe”.

That's not what the FDA is saying. What the FDA is saying is, “We need more testing here to give it this designation”, but I think the history of the FDA and the history of food science and technology suggests we're likely to see these ingredients getting Generally Recognized As Safe designation and even without all these formal designations, being consumed by the public as we consume lots of things that are in these sort of gray areas from the FDA perspective.

CURWOOD: So, how much dough is invested in Impossible Foods and the other meat alternatives generally do you think?

BROAD: Well, "do you think" is the big important part of that question because a lot of the stuff this things that we don't know. Right? These are private companies that keep information about funding pretty tight to the vest. We do know that Impossible Foods had a recent funding round that was in the $75 million dollar range, so they've had a couple hundred million dollars put into them at this point. Other companies in this space like Beyond Meat have gotten, you know, several tens and hundreds of million dollars investment from a variety of venture capitalists, but a lot of the entrepreneurs won't tell us exactly what they're working with.

CURWOOD: So, what are environmental groups and food activists saying about Impossible Foods and the Beyond burger and so forth?

BROAD: I don't think that environmental groups and food activists speak with a unified voice on this topic. There are some who are generally supportive of this development in large part because they recognize the environmental harms that are caused by contemporary animal food production; however, there are certainly some other groups that have raised concerns.

Friends of the Earth is one of the more vocal in this arena, and they are concerned as much about process as they are about product. They have concerns about sort of who is making decisions about what we're going to eat and the transparency in the regulatory process. And, you know, some of these groups have just general skepticism and concern about genetic modification specifically, which they see as potentially environmentally harmful, potentially harmful to human health, but also a lot of their critique is about sort of who controls food, who’s the driving force of our food system.

Garrett Broad is an Assistant Professor of Communication and Media Studies at Fordham University. His research focuses on food justice and sustainability. (Photo: Fordham University)

CURWOOD: So, Garrett, my crew was lucky that they got to have an Impossible Burger. I've yet to have one. I did get to try a Beyond burger, and what I want to ask is, how long is it going to take for these plant-based burgers from a biotech company like Impossible Foods to make it beyond the specialty restaurant, beyond the specialty food aisle of, of, right now, I mean, you can get these in upscale grocery stores but not at usually the neighborhood ones.

BROAD: So, we've seen a lot of growth in just a few years. I mean, plant based replacements, remember, have been around a long time, right? We've had veggie burgers, we've had tofu and tempeh, but we've seen those have had a very limited market share right? And so these folks who are doing these plant-based burgers are seeing significant growth over just the last few years, but as you say much of that has been at, you know, upper-end grocery stores or at upper-end restaurants.

Some of that's changing, so Beyond Meat which you've mentioned has a deal with Safeway, and so there are now at some major mass market grocery stores up and down California primarily. You know, you've also seen folks like Richard Branson who's invested some money into kind of the future of food space in general, say things like, you know, in 30 years he doesn't think will be eating “real” quote unquote “real” animal protein at all. I think that's probably an overstatement, but I do think that it's important to remember the way that our conventional meat is in many ways subsidized to keep the cost low. Right?

And so if we paid the full cost of a beef hamburger, taking into consideration all of the costs to environment, to, potentially, health, you know, that couple-dollar burger from McDonald's really costs more. And so that's an argument that these folks make too. If we were able to have a level playing field here, these prices could get to parity even quicker. But there is still a way to go, and I think that's something that, with scale and with time, I think, yeah, something like a quarter of the market in the next 20, 30 years that would be huge going from this very niche space that we're in now.

CURWOOD: Garrett Broad is a Professor of Communications and Media Studies at Fordham University, when he's not cooking various meat alternatives. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

BROAD: My pleasure. Thank you.

Related links:

- Civil Eats: Garrett Broad on Meat Alternatives

- Beyond Meat

- Garrett Broad

[MUSIC: Lalo Schifrin/studio orchestra, “Mission: Impossible Theme” on Music From Mission: Impossible, Hip-O Records]

American Seafood: Heritage, Culture & Cookery from Sea to Shining Sea

Fresh Spanish mackerel on ice, just before being taken to Barton Seaver’s kitchen to be gutted and cooked. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

[STREET SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Late one morning on a brisk fall day we’ve come to Portland, Maine, to talk with celebrity chef and author Barton Seaver. His new 500-page book is called "American Seafood: Heritage, Culture and Cookery From Sea to Shining Sea". And he asked us to meet him at a popular fish market that backs onto a dock loaded with lobster traps and buckets of bait fish.

[SOUNDS OF FISH MARKET, WATER, DUMPING CRATES, ETC.]

CURWOOD: Inside the market it seems there's fish and ice everywhere.

The storefront of Harbor Fish Market in Portland, Maine. (Photo: Corey Templeton, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

SEAVER: So, we can start over here on this wall and see 20 kinds of oysters - John's River, Nonesuch, Wawenauks. So, you've got Damariscottas. You've got Dodge Cove, Glidden, Wiley. I mean, these are some of the truly charismatic places of the Maine coast, each of these representing a “miroir”, if you will, each oyster a taste of the people, the place, the tides, the currents, the history. You can see the different environments are reflected quite literally in the shape of the oyster shells and the color of them. You see here, these Nonesuch have a green hue to them. That's a marine algae that grows on the outside.

CURWOOD: I enjoy oysters, but I've never actually tried to shuck one at home. If I bought these, what would I have to do to open it once I got them home?

SEAVER: There is the fact that most Americans are put off by that this is food that inconveniently comes wrapped inside of a rock. [LAUGHS] But oysters were once of the most popular food in America. I mean, there were the food of both the rich and the poor. Penny oyster bars lined the Lower East Side, you know, carts, saloons, and speakeasies that celebrated this culture.

Oysters reflect their local “merroir”, taking on a particular flavor based on the environment in which they grew. Their looks are also borne of their origins: above, Nonesuch oysters – so named for the Maine river estuary where they’re cultivated – are naturally green with harmless algae and stand out among twenty or so varieties. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

So, something interesting I'd like to point out to you as we walk over to the fillet fish case, here. They’ve got 25 different kinds of fish. Half of them are orange, meaning half of them are salmon type - Arctic char. You've got farmed salmon coming from four different countries. We've got two different kinds of wild salmon coming from Alaska. We've got trout in the back there which is a salmon relative. So, our species preference in America is really very limited. Americans love shrimp, tuna, and salmon. Over 65 percent of our total consumption of seafood in this country is just those three varieties. But what's great about this market is that, yeah, you've got farmed salmon from Chile, from the Faroe Islands. You've got King salmon and Coho coming from Alaska. Next to it you've got halibut and haddock. You've got bluefish. You've got cod...Cusk, a member of the cod family.

So, interwoven between these international commodities seafood trade is the heritage, is the fish, the very backbone upon which New England and her communities were founded. Cod is to New England as cotton was to the south. You know, it was the commodity upon which the wealth of this nation first began to accumulate. It was how we began to take our first steps towards independence by becoming a mercantile nation.

Typically, at least half of the fillet varieties offered in a seafood market are what Barton Seaver calls “orange fish” – in other words, those in the salmonid family: salmon, trout, and char. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

We continue over and right in front of us is a representation of our bioregion in the form of whole fish. Most chefs have never seen or worked with whole fish, let alone consumers.

CURWOOD: So, I want a little advice about fish buying. I'm not an expert at all on this, but I'm looking at this mackerel, and it looks really great. For some reason, it's shiny, and what should the buyer of seafood especially whole seafood be looking for aside from using one's nose of course?

SEAVER: If you look at the eyes, basically what you're looking for in summary is vibrancy. You want it to look as close to living as possible. Here with a mackerel you still see this little murderous underslung jaw as though it's still trying to intimidate you. You see this flesh, you see that it bounces back with gentle pressure, meaning that it's still firm and you see that in this really gentle light that we're under here, you see that it's reflective. This thing is close to alive. It is a shiny, beautiful, gorgeous specimen, and, if you can't say that about the fish, I don't think it's worth buying.

CURWOOD: Barton, at one point in life I heard someone say, “The best fish to buy the market is the cheapest.” Why? Because it's the freshest. They have...Tthe most anxious to get rid of. What do you think of that old saw?

SEAVER: Cheapest might not be the best way to go, but certainly the question there is what's the catch of the day? Well, hey, today, ocean perch. It is abundant right now. The fisheries are just killin' it, bringing it in day after day. This fish was just landed yesterday on the exchange in Portland [Maine] just yesterday morning. Beautiful fish. Just out of rigor. Today we've got it for $3.99 a pound. Wow! What a great deal.

Harbor Fish Market is located on Portland, Maine’s working waterfront. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: And it seems to be about the cheapest fish there.

SEAVER: There's that benefit too. But what we do when we walk into a grocery store, really into any retail scenario, and we say, “My recipe says red snapper,” we are making demands not only of this business, we are making demands of fisherman beyond that service business, and ultimately of the ecosystem. And, when we act with such hubris to think that it's our place to tell ecosystems and fishermen only what we're willing to eat rather than ask of them what they are able to supply, we are creating inherently unsustainable systems.

CURWOOD: Well, we've been trained with factory farming. I mean, I don't know as consumers that we're really trained to think about buying what's available and what's smart as opposed to what the recipe book says.

SEAVER: We're beginning to get there, and, to be quite honest, I mean one of the great victories in, of humankind is the fact that we're able to produce so much food, and there's a lot of controversy about how we do it. But the fact that we are able to feed so many, easily a victory.

CURWOOD: Frankly, I do enjoy eating, I got to admit it.

Fishermen with cod and halibut, Alaska, 1927. (Photo: Courtesy of Library of Congress)

SEAVER: Hey I do too. Oh yeah, but you know I think people are beginning to sense that through food we connect to civic-social virtues, values in ways that are very exciting that make food an exploratory opportunity not just a satiation exercise.

CURWOOD: Barton, I grew up in Boston, and close family friends, the dad worked as a longshoreman and would bring mackerel home to cook and fry. I don't think since I was a teenager I've seen a whole mackerel.

SEAVER: Well, why don't we pick some of those up and take him back to my kitchen and we'll help re-live some of those memories for you.

CURWOOD: Alright!

[MUSIC: Crooked Still, “Come On In My Kitchen” on Shaken By a Low Sound, composed by Robert Johnson, Signature Sounds]

CURWOOD: Coming up, Chef Barton Seaver takes us home to share his secrets for savory seafood. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Three specimens of the “true mackerel” variety. Mackerel is a common name that refers to a variety of species of pelagic fish. (Photo: Michael Piazza)

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Crooked Still, “Come On In My Kitchen” on Shaken By a Low Sound, composed by Robert Johnson, Signature Sounds]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC ON THE VICTROLA: King Oliver and his Creole Jazz band/Louis Armstrong, “Alligator Hop,” on King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band: Alligator Hop, composed by King Oliver, Gennett Records]

CURWOOD: We’ve come to the 200-year old home of celebrity chef Barton Seaver. It’s just up the hill from a Maine coast harbor, and just inside the door there is an old-time Victrola that Barton has cranked up to give us a bit of King Oliver and his Creole jazz band.

[MUSIC]

And, while his kitchen fits nicely into the antique décor, it is strictly modern for Barton when it comes to the cooking.

[SOUNDS OF UNWRAPPING OYSTERS]

SEAVER: So, you were asking earlier about how, how to open an oyster. Well, that's how it is one of the only foods we eat that comes inside of a rock, and the way to open it is to take the rock in one hand, take a sharp object - basically the shank - in another hand point the shank directly at your other hand and then pry with strength. There's a reason why people are pretty intimidated by this.

[LAUGHS]

Catch sizes have shrunk dramatically over the years. (Photo: Courtesy of Monroe County Public Library)

So, we've picked up the two different providences of oysters here. So, this is the Nonesuch oysters of my friend Abigail Carrol. She grows these smaller oysters, beautiful shell hinge on them, and these are wild oysters from Damariscotta, powerful tidal river up the coast. You can see, they're just a little bit more unruly in their shape and form and size, and, well, they are a little bit dirtier. It doesn't make them any less, any less delicious, in fact, they both will give off their own charm and unique qualities, and that's the whole point of an oyster.

CURWOOD: What's the secret here, Barton? You got right into that oyster, no problem.

SEAVER: Well, the two shells are held together by the adductor muscle right, in the center. When you look at an oyster, you think it's the round little disc in the middle. That's actually the same muscle that you...That's what we would call a scallop in the scallop animal. In that animal, though, we only eat that muscle. That muscle holds the two shells together. The top shell is flat. The bottom shell, cupped, holds the body of the oyster. You go in through the very back, where the shells meet in the hinge, and once you get the knife between the shells, use a twisting leverage to separate them just enough so that you can get the flat angle of the knife to then slide along the underside of the top shelf and thus slice the adductor muscle free. At that point the oyster is connected to the bottom shell by that same muscle, you scoop out from below, and you have an oyster sitting there jiggling with all of that fresh, beautiful brine and liquor.

Chef and author Barton Seaver at work on a lobsterboat. (Photo: Michael Piazza)

CURWOOD: My mouth is watering already. Thank you. Mmmmmm. Wow. Just fresh....little touch of seawater...really bright.

SEAVER: So, that was the wild Damariscotta. This is the Nonesuch oyster, same species of oyster.

[CURWOOD SLURPING]

CURWOOD: Even more intense flavor to this one with a sort of sweet finish to it. So, you're from the Tidewater area? Chesapeake?

SEAVER: Born and raised, son of the Chesapeake, really the son of downtown DC during a relatively tough time in its history, during the mid-late '80s when crack had just really hit as an epidemic. So, as a means to escape some of that during the summer we spent a lot of our time down on the Chesapeake Bay, a tributary called Patuxent River.

[SOUNDS OF SHUCKING OYSTERS]

There I learned my appreciation for seafood and also learned my understanding of the bounty of waters and created in my mind what, what you call my baseline, what I understand “bounty” in this world to be. And it's a real interesting thing in conservation is that we create an idea of what we think is normal based on our experiences, and then we fight. We fight with all that we are to sustain that, to get back to that normal, but in many cases that normal is so far from pristine or pure or truly sustainable that, when we talk about ecological baselines or even social baselines, we get to the question about sustainability is that, what is it that we are trying to sustain at the end of the day?

Crimping the skin of fish like this Spanish mackerel prevents the fillet from curling in the hot pan. (Photo: Barton Seaver)

From a biological standpoint, we often have no true understanding of what level of biomass or of diversity that we're trying to restore, really, but, when it comes to a social baseline, that's where sustainability becomes understandable. It becomes actionable, measurable, and valuable because what I'm trying to sustain is 5,600 individual licensed owner-operator lobsterman and women along this coast. I'm trying to sustain my neighbors. I'm trying to sustain the fisheries that have forever, since white man populated this area, sustained these communities.

And when I say sustained, we're talking about fisheries here. A lot of people don't understand what a fishery is though, and I want you and your listeners to practice this exercise. Close your eyes and picture a farm. Rows of corn, autumn, splendor, setting sunlight, red barn, gently reflecting back, a one and a half lanE dirt road trailing off into the distance, iconic America, amber waves of grain, the fruited plain. That was easy. I mean, it is rooted within us. Now close your eyes and picture a fishery.

After filleting the Spanish mackerel, Seaver makes a simple cut on either side of the spine to free it and all the bones of the fish in one simple step. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: It's dockside. For me, it's dockside. It's Boston. It's an area that fishing boats, I don't know if they land so much there anymore, but they used to land there when I was little. It's noisy, and there's lots of wooden boxes and men running around hand trucks and hollering and ice and water splashing everywhere.

SEAVER: Well, this is what people don't often understand. What you just described is, is an industry. It is people, it is action, it is movement, it is an economy. Too often we stand on that dock and we gaze wistfully out of the wine-dark sea and think that a fishery is something that happens over the horizon of our attentions. But you're right. A fishery...You stand on that dock and you hear the sound of those jobs in motion. You turn around you look at the houses and schools and the roads and the quality of life for those people living in that community. And a fishery to me is the ability for a son or a daughter to follow in five generations boot steps onto the helm of that boat to take care of the heritage and legacy of their family. And when we talk about sustainability, if we talk in those terms of saving things that we as humans value, then the ecosystems become the tool by which we remain resilient, and that way I think we turn sustainability around to really be human interest rather than a separate, ecological interest, and then think this is where we make it actionable. We take an oyster in our hands, we slurp it down with a local beer, and we say, "Wait a minute. That's environmentalism? On the half-shell with a six pack? I'm in, buddy!"

Large scallops fished with a dredge, c. 1960. (Photo: Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Unfortunately, as I think about it, that place that I that I recall as a kid, I think it is a hotel now.

SEAVER: That's part of the hard truth of fisheries is that they happen on very valuable property.

[RUSTLING SOUNDS OF UNWRAPPING FISH]

SEAVER: So, every good fish butcher is going to have their own chosen knife. I've got mine that's been with me for 15 years, almost 20 at this point actually. So, Spanish mackerel, just a very shallow slice right behind the nape, right behind the gilt plate. Draw the knife straight through, one simple straight easy cut. Flip the fillet over, note gaping beautiful just milky light flesh. They didn't eviscerate the fish. It's just so fresh, and the texture is so clean. And that's it, filleting a fish. I love coming home with a whole fish because I like to make stock with the head and the bones here, but more likely that will end up in the compost, fertilizing next year's tomato crops.

One of the things I love about mackerel is the bone structure is so simple. One might call it satisfying, so that a simple slice on either side of the bones that run directly down the middle of the fish. I don't puncture the skin or go through. Then a simple flip of the knife underneath, and I can just peel back, in one strip, all of the bones encased in a very thin sort of sheath of flesh that keeps the entire fillet intact. Beautiful, boneless, cooks evenly, that golden mottled skin with reflective, silvery, cutaneous fat. Beautiful fish. Beautiful fish.

Flames leap up from the pan as Seaver finishes the pan-seared Spanish mackerel in a rum flambé. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

I like to heavily season mackerel. The flesh is so fatty at this time of year as they’ve been stalking with those little murderous underslung jaws, alewives and capelin and all sorts of fish up and down the coast as they've been marauding schools of baitfish, and they're so fatty that the salt is needed to kind of tense up the flesh and to bring it together says it has a nice density when it cooks out. So, like with all fish I tend to leave it to salt for about 20 minutes, so the salt penetrates evenly, doesn't just sit on top but actually becomes part of the structure, and part of the texture and really has its chemical effect all the way throughout, adding to that density. Next ingredient, well, this is fresh garlic strewn out of, straight of our garden. It’s a type of garlic called Music. All right, now we just enjoy some of this beer until that salt kind of kicks in, and we'll start sauteeing up.

[LIGHTING THE STOVE]

SEAVER: So, we're doing a very simple straightforward dish. It might sound a little complicated, but it's kind of four ingredients. You got your fish. We're going to saute it in butter, herbs and lemon. Well then, I'm going to add a fifth ingredient just for you, Steve. We're going to, we're going to blow this up.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Blow this up, Barton?

SEAVER: Yeah. Well, this is New England, so I'll throw some rum on there just to vary it and do a little flambe, just to get your spirits rolling. So the butter is going in.

[SIZZLING]

SEAVER: Then the lemon, herbs, and garlic. And then, into each goes the fillet. I use the herbs to baste the fillet with some of that brown, garlic-infused butter, rub that onto the fish a little bit. You see the lemons beginning to carmelize and beautiful. The rims are burned, just beginning to smell. It smells incredible.

And now, you take that fish. You can see it. It didn't even have an idea of sticking to the pan. One of the keys there is using high heat, and that fish is going to be cooked through here in just under five minutes or so.

And then, Steve, once for New England. I'll turn the burner back on here for myself a little myself a little room. Now, we're going to flambe this. So I'm going to give this a shot of rum. This is good old Havana.

The finished Spanish mackerel, pan-seared with butter, herbs and rum. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

[SIZZLING]

A little bit of butter on top. Let it melt in, create that sauce. Take that carmelized lemon, drizzle it over to finish it out. And there we go. Pan-seared mackerel with herbs and a shot of rum.

CURWOOD: Wow, you make it look so easy, but it's not.

SEAVER: You know, truth be told, let's take some things out of this recipe. Let's take out the booze. Let's even take out the garlic and, heck, you can take out the herbs or the lemon, and what you've got here is a cast iron pan. You've got a beautiful piece of fresh fish, the catch of the day down there, the best looking fish they had at the market. Bring it back here. What is it? It's fatty, late autumn, beautiful mackerel. So rich, that fat renders off on your fingers just by the touch, salt it, and just let the salt sit until it absorbs deeply into the flesh. Saute it in hot pan in nothing but butter. Let that skin crisp up just three minutes until it begins to just show a little bit of doneness along the sides. Turn it over and turn the heat off. Wait another three minutes. It's cooked all the way, through, gentle, slow, and you have a beautiful piece of fish that tastes like everything beautiful the ocean has to offer. Bottom line is, cooking good fish is as simple as this. Buy good fish.

[SOUNDS OF CUTLERY]

SEAVER: All right!

CURWOOD: So what's the word? “Bon?” The second word is “appetit?”

Barton Seaver and host Steve Curwood with Seaver’s new book, American Seafood: Heritage, Culture & Cookery from Sea to Shining Sea. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

[SOUNDS OF CUTLERY]

CURWOOD: Don't need a knife for this. Oooh!

[FORK SCRAPING PLATE]

CURWOOD: OK, this is not your fried mackerel. This is amazing mackerel. It literally melts in my mouth, and yet it has that little kick that mackerel is, a little sense of oil and ocean and effort or something that is in that.

SEAVER: The taste of vigor. These are active strong beautiful dart like fish that can swim at ungodly speeds. Wow, are they amazing in water and amazing out of the water.

You know, when we go to the fish market it's so important to just ask what's the catch of the day, to participate in a...to behave in a sustainable manner once we walk through the door. If we come in with our own, carrying our own demands of fishermen, of the fish market, of the oceans themselves, demanding only what we're willing to eat rather than asking of them what they're willing and able to supply, we walk out with the best piece of fish that we can. But in order to do that, in order to really enjoy this fish we have to practice liking them. We have to practice understanding and knowing their flavors and their their charisma and their character, and we're not accustomed as a culture to liking mackerel or liking sardines even any more. Mackerel was once the most important valuable and favored fish in all the land. If we shipped the salt cod overseas, it's the mackerel that stayed in the kitchens here.

[SOUNDS OF CUTLERY ON PLATES]

SEAVER: Mmmmm, actually pretty good.

CURWOOD: Barton Seaver's new book is called "American Seafood: Heritage, Culture and Cookery From Sea to Shining Sea". Barton, thank you so much for this, well, delicious encounter.

SEAVER: It is such a pleasure, and what a way to end with a little jazz and a great meal.

[MUSIC ON THE VICTROLA: King Oliver and his Creole Jazz band/Louis Armstrong, “Alligator Hop,” on King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band: Alligator Hop, composed by King Oliver, Gennett Records]

Related links:

- American Seafood: Heritage, Culture & Cookery from Sea to Shining Sea

- Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch helps consumers choose sustainable fish

- Barton Seaver met up with host Steve Curwood at Portland, ME’s Harbor Fish Market

- About the Nonesuch oyster

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth