October 15, 2021

Air Date: October 15, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Reconciliation, Climate and the Environment

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

Multi-trillion-dollar measures are being discussed in Congress that address much of President Biden’s domestic policy goals, including those for the environment and combating climate change. Host Steve Curwood talks with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran to get an idea of what these bills are about. (07:06)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Environmental Health News editor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about the recent awarding of the Nobel Prize to three scientists who have made crucial contributions to the field of climate science. Next, the two discuss a study linking Lou Gehrig’s disease to pesticide use. Finally, they take a look through the history books to the oil embargo and gas lines in the United States in the 1970s. (04:50)

Phthalates Linked to 100,000 Yearly Deaths

View the page for this story

Phthalates are a group of chemicals commonly found in plastics, to the extent that they’re often referred to as “everywhere chemicals” with a wide variety of health effects. Detailed statistical analysis conducted for a new study in the US finds that people aged 55-64 with documented phthalate exposure a decade earlier died at a rate of over 100,000 people a year, most commonly from cardiovascular disease. Persons in other age groups aren’t exempt from risk; indeed phthalates are considered by some to pose the greatest risk to children in the womb and during early years of development, though so far other studies have been more limited in scope. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb talks to Dr. Leonardo Trasande of NYU, the lead researcher on the newly published study, about how to avoid unnecessary exposure to these chemicals that can sometimes seem unavoidable. (13:26)

BirdNote ®: The Tui of New Zealand

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

The Tui is one of New Zealand’s most remarkable birds. As BirdNote’s ® Mary McCann reports, these intelligent birds are one of only a few species in the world that can mimic human speech. (01:54)

Bewilderment

View the page for this story

Richard Powers, the author of Pulitzer Prize winning novel “The Overstory”, is back with a new science fiction book, “Bewilderment”. The novel follows a father, Theo, and his son, Robin, as they navigate environmental issues like a growing species extinction crisis, alongside personal concerns like the recent death of Theo’s wife and Robin’s combined autism, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Richard Powers joins host Steve Curwood to discuss “Bewilderment” at the first Living on Earth Book Club event of Fall 2021. (19:11)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

211015 Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Richard Powers, Leonardo Trasanade

REPORTERS: Paloma Beltran, Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Green energy and the multi trillion-dollar infrastructure bill working through Congress.

CASTEN: If we go out and we build out all the things in this bill we are going to have a grid that costs no money to operate. And you have amazingly cheap energy which is also amazingly reliable energy.

CURWOOD: Also, researchers find phthalate chemicals are associated with more than 100,000 premature deaths in the US each year.

TRASANDE: We found that levels of phthalates were consistently associated with increases in mortality. And particularly it was a specific sub-group of phthalates, the phthalates that are typically found in food packaging. They're these soft wraps that you see in healthy food as well as unhealthy food.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Reconciliation, Climate and the Environment

Representative Sean Casten (D-IL) serves on the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. (Photo: National Renewable Energy Lab’s Photostream, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

President Biden’s domestic policy priorities have been compiled in a giant twenty four hundred page bill with many elements, including some that address the environment and combat climate change. To bypass a likely Republican filibuster in the Senate Democrats are putting as many things on their legislative wish list as possible into this bill, using the federal budget reconciliation process that usually only happens once a year. So, with a razor thin majority in both houses every Senate Democrat and virtually every House democrat will have to vote for it. Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran joins me now to explain what’s at stake in this bill when it does comes the environment and climate. Hi there Paloma!

BELTRAN: Hi Steve!

CURWOOD: Well, generally what are we talking about in this bill that would affect the environment and climate change?

BELTRAN: So there’s a lot. I talked to Matthew Davis, he's the Legislative Director for the League of Conservation voters and he pointed to a few critical parts of the bill.

DAVIS: One of the things that I think is, really important about the build back better act is how much environmental justice is, has been woven throughout the bill. The greenhouse gas reductions fund, also known as the Clean Energy accelerator. And there's a portion of that about $8 billion out of the $27 billion that is targeted toward solar installations in low income communities. And so that's a program where you can see really, I think, important targeting and making sure that the clean energy investments are going to those communities that have borne the brunt of fossil fuel pollution over the decades.

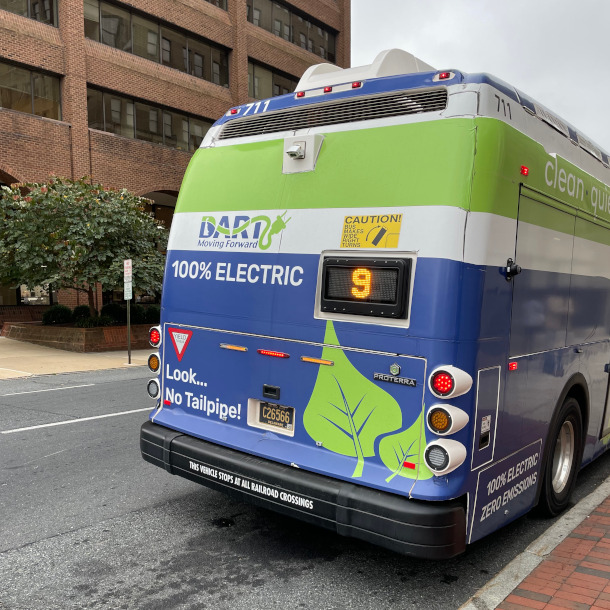

President Biden wants to have half of the vehicles in the US be electric by 2030. (Photo: City of St. Pete, Flickr CC, BY-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: There’s also money to clean up superfund and brownfield sites, as well as abandoned mines and oil and gas wells. And that’s worth noting because research shows that those living or working close to a superfund site show higher levels of serious health issues like cancer and birth defects. There are also lot of communities throughout the United States that struggle with lead pipes that pollute their drinking water.

DAVIS: This bill would provide additional funding to get those pipes out and make it easier for lower income communities and utilities that have a lot of low income customers to get 100% government funding to replace those lines. And that makes a really big difference in terms of drinking water quality, and the health of as their brains are developing.

BELTRAN: The bill also tackles methane, which is 80 times more powerful than CO2 as a greenhouse gas when it’s released. Methane emitters such as oil and gas wells and pipelines would have to pay a fee aimed at making sure they meet emission reduction goals. There’s also funding for coastal communities to improve resiliency.

DAVIS: This would be things like restoring and protecting wetlands along the coast or along river ways. This helps both absorb more carbon dioxide out of the air, which is important to help, you know, reduce the effects of climate change. But it also helps buffer towns and communities from storm surges and rising sea levels.

BELTRAN: Matthew Davis also pointed to funding for the US Department of Agriculture to address massive wildfires as well as for conservation programs that would absorb and maintain carbon in the soil.

The Reconciliation package includes funding for the Bureau of Land Management to improve conditions at superfund sites like the Formosa Mine Superfund site above. Acid mine drainage out of the Formosa Mine Superfund site in Southwest Oregon has been an ongoing problem for many years. (Photo: BML, Flickr, CC By 2.0)

CURWOOD: What about electric vehicles?

BELTRAN: Yeah Steve we know that President Biden stated that he wants half of the vehicles in the United States to be electric by 2030. A big portion of US emissions reductions are expected to come from upping EV charging stations and EV purchase incentives. The bill would keep an existing EV tax credit but also provide an extra tax credit for vehicles assembled in the U.S. by unionized companies like Ford and General Motors. There’s also an incentive for purchasing inexpensive used EV’s that may help low and moderate income households transition away from gasoline vehicles.

The government would electrify its own fleet and pay for some electric school buses especially for rural and low income communities.

DAVIS: Those changes, I think, will be the kind of thing that people see right away, you know, they'll wake up in the morning and bring their kid out to an electric school bus to ride to school will have clean air to breathe when they're dropping the kid off. And they'll have the assurance of knowing that their child will be in a bus not, you know, choking on diesel pollution, but instead having clean air to breathe all the way to school.

CURWOOD: What do you hear is seen as the most transformational part of this bill?

BELTRAN: Well I talked to Representative Sean Casten, a Democrat from Illinois who’s a member of the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. And he points to the huge energy transformation that will result from shifting the grid from fossil fuel energy to low carbon sources.

CASTEN: Well, here's the most important thing. And this is about climate change writ large we are on the cusp of the biggest wealth transfer from energy producers to energy consumers in our history as a species. That's a really, really big deal. Because if we go out and we build out all the things in this bill, we are going to have a grid that costs no money to operate to a significant degree. Because if you think about it how much does it cost to run a solar panel, same thing, geothermal, same thing, insulate your home doesn't cost you anything on the margin. Like you have to make the investments, right? But then you build all these things out. And you have amazingly cheap energy, which is also amazingly reliable energy.

Joe and Jill Biden live in Greenville, Delaware, an upscale suburb of Wilmington that is served by the DART public transit bus system. (Photo: S. Curwood)

BELTRAN: Representative Casten said that if the language of the bill stays as it is there would be a 35% to 45% reduction in CO2 emissions relative to 2005 by 2030 and over 1000 gigawatts of new clean electricity generation installed.

CASTEN: For context, the total installed generation capacity in the United States today is 1000 gigawatts. So we're talking about in a nine year span, creating millions of jobs building these assets, drastically lowering people's cost of energy. And if we're doing it smartly, doing it in a way that makes sure that those benefits are equitably distributed throughout our society, it is truly transformative.

BELTRAN: And with the COP 26 summit in Glasgow right around the corner US lawmakers like Representative Casten are hoping President Biden can have action instead of just promises to bring to the table. At the top of the list is congress passing the Clean Electricity Energy Program that would effectively decarbonize the nation’s energy sector.

CASTEN: It is extremely important that we pass these bills before November, when we will be back at Glasgow, for the next conference to put this down. Both because we as the United States, I want us to be in a position of leadership. But also, because the rest of the world wants us to be in that position of leadership.

BELTRAN: Gaining credibility in the international climate negotiations is important.

And even more important, would be the first ever passage of comprehensive federal laws to fight climate change with science based solutions in a way that also helps achieve the stated goal of addressing environmental justice.

CURWOOD: That would indeed be historic. Thank you Paloma!

BELTRAN: Thank you Steve!

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Related link:

Read the full 2022 Budget Resolution Agreement Framework (The Reconciliation bill)

[MUSIC: Entrain, “Hear That Long Snake Moan” on “Hear That Long Snake Moan” by Entrain, Dolphin Safe Records]

Beyond the Headlines

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics has been split among scientists Syukuro Manabe, Klaus Hasselmann, and Giorgio Parisi. (Screenshot from The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm)

CURWOOD: It's that time of the broadcast when we turn to Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. And he's going to take a look beyond the headlines for us from his perch there in Atlanta, Georgia. Hi there, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: I have the second time that climate change has been the topic for the awarding of a Nobel prize, Syukuro Manabe, Klaus Hasselmann and Giorgio Parisi share the prize for three different studies, three different pieces of work, that quote in the words of the Nobel Committee, demonstrate that our knowledge about climate rests on solid science.

CURWOOD: What do these folks demonstrate through their research about climate change?

DYKSTRA: Well, Manabe is based at Princeton, and in 1967, we don't normally talk about climate change papers that were done so long ago, but he put together research and how increased levels of CO2 would lead to higher temperatures. That, of course, is one of the basic elements of climate change. And it led to the development of all future work in climate.

CURWOOD: And what about the other two folks?

DYKSTRA: Hasselmann is from Germany. Parisi is from Italy. They wrote separate papers on how, with Hasselmann, the melting ice in Greenland can eventually cause climate chaos around the world. And Parisi wrote a paper that was applied to climate change, about how many seemingly disparate things can come together to be the crisis we know now, and the crisis we'll know in the future.

CURWOOD: That's right, Peter, I wish it was going away, but I don't think it is yet. What do you have next for us?

DYKSTRA: Well, every year in the US there are approximately 5000 cases diagnosed of ALS, that's amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. It's also known in this country as Lou Gehrig's disease, because it struck down the baseball player in the late 1930s. What ALS does is it knocks out nerve cells that connect the brain to our muscles, and various bodily functions: the ability to walk and talk and eat, use your arms, use your legs are taken away, often in no more than two to five years. Although some ALS survivors can last a lot longer than that. The cure isn't known yet. But the research into the cause published in the journal, Neurotoxicology says that one of the causes may be linked to pesticide use.

Pesticides are linked to a number of health concerns, both acute and chronic. A new study is adding to this long list of negative health consequences by showing a link between pesticide use and Lou Gherig’s disease, also known as ALS. (Photo: Sharon Dowdy, UGA CAES, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: But now we have a potential contributor - our pesticides?

DYKSTRA: Things like paraquat and a lot of very common pesticides used on crops around the world, may be a link to ALS. It's a new one and one that raises further concern that restrictions on some pesticides haven't gone far enough.

CURWOOD: But also raises hope that we may be able to address this killer disease. Let's turn now the history books and take a look back, tell me what do you see?

DYKSTRA: I see long gas lines back in the 1970s. The first of which started on October 17, 1973. The members of OPEC, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, were angered by the United States support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War, in which Israel defeated Egypt and Syria.

CURWOOD: And OPEC was largely made up of Middle Eastern countries.

DYKSTRA: That's right, countries that have a long standing conflict with Israel. What happened when that embargo was put in place, is that the energy crisis, as we called it here in the United States, saw gasoline prices quadrupled due to short supply. And that short supply created enormous gas lines at the pump.

CURWOOD: You know, fairly recently the people in the UK have seen gas lines with some problems getting petrol there. And of course, the price of natural gas has shot up rapidly. But instead of Middle Eastern countries involved in this, people are pointing the finger at Russia. And these gas lines, I think are rattling the public about things like the climate negotiations that are about to happen in Scotland.

DYKSTRA: That's right, and that'll be a topic front and center. We're also waiting to see what happens with legislation here in the US that would better enable a transition to clean energy.

CURWOOD: Alright, Peter. Well, thank you. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. And we will talk again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Sure will, Steve, thanks a lot.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “Nobel Prize in Physics Honors Work on Climate Change”

- Environmental Health News | “Higher Estimated Pesticide Exposures Linked to ALS Risk”

- Read more about the 1973 Oil Embargo

[MUSIC: Thomas Mapfumo, “Pasi Hariguti (The Earth’s Hunger Is Insatiable)” on Rise Up by Thomas Mapfumo, Real World Records]

CURWOOD: If you like what you hear at Living on Earth please join us with a gift of $5 or more. Just go to LOE dot org and click on donate at the top of the page and thank you!

Phthalates Linked to 100,000 Yearly Deaths

Often, produce is wrapped in plastic which contains harmful chemicals. Phthalates used in many products to make plastics more flexible then are carried along by the food and we can easily ingest them. (Photo by Simmremmai, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: I’s Living on Earth I’m Steve Curwood.

A new study published in the journal Environmental Pollution found phthalate chemicals are associated with more than 100,000 premature deaths each year in the US. Researchers looked at National Health data which included phthalate levels in urine and cause of death. They correlated high phthalate levels with elevated cardiac death rates in people aged 55 to 64. A number of sources indicate phthalates can be found in countless consumer products including food packaging, shampoo, children’s toys, flooring, perfume, detergents, the list goes on and on. The health problems associated with phthalates include obesity, cancer, asthma, and heart problems just to name a few. Phthalates are dangerous because they can act like hormones in the body, and fetuses and children are especially sensitive to hormone disruption during development. Phthalates interfere with testosterone, which is present in both men and women, and exposure during pregnancy has been linked genital development problems and autism traits in boys. But the health effects of these chemicals aren’t easy to quantify so this new study has remarkable statistical clarity about they may contribute to early death for people in middle age. Leonardo Trasanade is lead author of the study, professor of pediatrics, and directs the NYU Center for the investigation of environmental hazards. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: So, it would be unethical to expose some people to chemicals that we know are potentially toxic. So, how did you go about this research?

TRASANDE: We put together data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, a nationally representative sample of people who were enrolled between 2001 and 2010, and we linked their data to the National Death Index. Which not only identifies, unfortunately, when people pass away, but it identifies causes of death that are listed on the death certificate. And so we looked at levels of phthalates in urine of these adults and related them to the time of death, or whether they died at all.

BASCOMB: And what were your basic findings?

TRASANDE: We found that levels of phthalates were consistently associated with increases in mortality. And particularly, it was a specific subgroup of phthalates, the phthalates that are typically found in food packaging. They're these soft wraps that you see in healthy food as well as unhealthy food. By the way, we controlled for diet and physical activity, and tobacco smoke exposure, which is important. We understand those are categories of exposures that are not good for you, in some cases, and are important to control for when you do these kinds of studies.

BASCOMB: And just to be clear, the people in this study, they weren't working in chemical manufacturing or anything like that, their exposure came from ordinary household products.

Children’s toys often contain phthalates. These harmful chemicals can be absorbed through the skin. (Photo: The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

TRASANDE: Yes, unfortunately, these are everywhere chemicals. These are chemicals that have come into such widespread use because of their utility, that they're in personal care products, cosmetics, food packaging. These are chemicals you touch and get into your skin and absorb into your body that way. You inhale them because they can get into dust that accumulates in homes. And because you eat on the go, especially, you can eat food that comes into contact with these chemicals, and the chemicals come along for the ride.

BASCOMB: And one of your key findings, as I understand it, is that phthalates may contribute to roughly 100,000 premature deaths each year in the US. What did the people in your study actually die of? We're not talking about, you know, acute toxicity or something here.

TRASANDE: That's right, we're talking in particular, the signal was strongest in relationship to heart disease, and ultimately death from heart disease. Now, we can't say definitively or in more detail whether it was heart attacks or stroke, and it was only one of the metabolites for which the signal was significant enough to meet our threshold for calling it important. The overall trend, though, is that across the US population, this equates to 100,000 55 to 64 year olds dying early. And that's in peak earning years. And when adults die early in those peak earning years that has an impact on our economy. The lost economic productivity we added up totaled $40 billion. That's an annual cost and so far as these exposures continue at current levels.

BASCOMB: And you found that these people were dying prematurely of heart related problems, but as I understand it, phthalates are known to cause a whole host of health concerns. Can you tell us a bit about that, please?

TRASANDE: Yes, of course, this is a single study. And when you observe a single study, you can't interpret that definitively to say for certain that it's linked to mortality. But the reality is that phthalates have quite the rap sheet across multiple populations, and multiple disease endpoints. Phthalates are known in the laboratory to disrupt metabolism and the hormones in our bodies, our basic signaling molecules, and they literally make us sicker and fatter. They, by disrupting those hormones in our bodies, they can contribute to obesity, and they can contribute to diabetes.

BASCOMB: Now, from what I understand previous studies have phthalates have found that this suite of chemicals are especially problematic for the endocrine system, which you just mentioned, and testosterone levels actually in men. Can you talk a bit about that also, please?

TRASANDE: So we know that the lower molecular weight phthalates, the phthalates used in personal care products, cosmetics, and such, antagonize the male sex hormone testosterone. And low T is either a predictor for or a marker of adult cardiovascular disease. And we've actually identified 10s of 1000s of men before this study who indirectly died because phthalates reduced their testosterone levels. We were expecting in this study, that only the men were going to have increases in death for that reason, because we thought, well, we know phthalates antagonize the male sex hormone. Lo and behold, we saw two things that were striking. It wasn't the phthalates used in cosmetics and personal care products that were associated with death, it was the food packaging, these higher molecular weight phthalates that were associated with death. And then when we looked further, it was not the men that were dying, it was the men and the women who were dying early in this pattern that appeared to be related to heart disease. Now, that's not necessarily so surprising because phthalates also cause inflammation in the blood vessels. And inflammation in the coronary arteries is not a good thing, it narrows the coronary arteries, you don't get as much oxygen to the heart. And that's what sets you up for heart attacks and even stroke.

Many personal care products and cosmetics contain phthalates which can be harmful to our health. (Photo by pmv chamara on Unsplash)

BASCOMB: Your study looked at exposure and health outcomes in people ages 55 to 64. Why look at that age group specifically?

TRASANDE: Well, in this study, we were only able to look at a single time point of measurement of the chemical exposure related to heart disease, and well, to death from heart disease and deaths due to cancer across 10 years of time. So there was a limit to how much we could interpret the data. And we wanted to be really careful. It seemed that the effects of these chemicals were concentrated in older populations. So there wasn't a difference in the degree of association. And so when we focus these estimates, unfortunately, we focused on the population in whom, you see earlier, heart disease.

BASCOMB: Now, how widely were phthalates used in household products, when people in the age range were coming of age? I'm wondering if they were exposed as children?

TRASANDE: Well, they were because these chemicals came on the scene, in the 1920s. The great news is these are not chemicals that are forever chemicals. What's important here about these plasticizer exposures, these phthalates chemical exposures, is that they tend to wash out of the body. They have a short half life. So about half of it gets out in two to three days. That's why studies have demonstrated easily in low income, as well as high income populations, that you can reduce your level in the urine quickly by taking safe and simple steps to reduce these exposures.

BASCOMB: Well, what can consumers do to minimize their phthalate exposure in light of this and you know many other studies that suggest there are potential health hazards here?

TRASANDE: So, there are safe and simple steps we can all take. They don't have to break the bank, they don't require a PhD in chemistry. Avoiding the use of plastic containers when possible, is important. Using glass or stainless steel is a great alternative. If you need to use plastic, particularly, please don't microwave or machine dish wash the plastic. That will facilitate the resorption of the chemical that's used in the lining that reabsorbs into food and gets into our bodies. And there's a recycling number on the bottom of the plastic bottle for a reason. The ones to avoid are three, six, and seven. Three are for the phthalates we're talking about here. Six is for styrene, a known carcinogen. And seven are for bisphenols. You all have covered BPA and its its relatives, and have shown how many health effects, not unlike what we're seeing here. In fact, we've published a study before this, showing early death in relationship to BPA. The phthalates we found here had their effects even when we added in BPA into our model so these are separate effects. And that doesn't mean that there isn't hope going forward for our health if we do the right thing now.

BASCOMB: Leonardo Trasande is lead author of the report and Professor of Pediatrics. He directs the NYU Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards, and is author of Sicker, Fatter, Poorer. Leonardo Trasande, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

TRASANDE: It was a joy. Thanks again.

Dr. Leonardo Trasande, the lead researcher on the study, “Phthalates and attributable mortality: A population-based longitudinal cohort study and cost analysis” published in the peer reviewed journal Environmental Pollution on October 12, 2021. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Leonardo Trasande)

CURWOOD: So, Bobby, this new study is really pretty troubling, considering how so common these products are.

BASCOMB: Yes, I mean they are called everywhere chemicals for a reason.

And after working on this story I started digging a little to figure out what people can do to avoid phthalates.

CURWOOD: Oh, and what did you find?

BASCOMB: Well starting with personal care products like cosmetics and shampoo.

You won’t see phthalates on a list of ingredients but we do know that they are used to make fragrances last longer, so if you want to avoid these chemicals you need to look for products that don’t include the word “fragrance” in the list of ingredients.

CURWOOD: Uh oh Does that mean I have to skip aftershave?

BASCOMB: Well maybe. It does mean you should dig a little deeper into the products you use to see what’s included in their fragrances.

CURWOOD: Hmmm….well, what about phthalates in plastics?

BASCOMB: Well, as Dr. Trasande mentioned, phthalates are in number 3 plastics, which is polyvinyl chloride or PVC. You can find that commonly in pipes and window fittings as well as some car parts, thermal insulation, and medical tubbing. It’s also in bubble wrap, shower curtains and some food trays.

CURWOOD: And what about food packaging?

BASCOMB: Yeah. If you look very closely at the bottom of most plastic containers you see the three little arrows that form a circle and inside that is typically a number. You can sometimes find the number three on soft, flexible plastic like clear food wrap, the kind that your meat might come wrapped in. It’s also sometimes in cooking bottles and cleaner bottles.

CURWOOD: Ok. Dr. Trasande also mentioned a couple of other types of plastic that are associated with health concerns. What did you find there?

BASCOMB: Yeah, number 6 plastic contains styrene, or Styrofoam, which is a possible human carcinogen. That’s used in insulation and Styrofoam takeout food containers, and hot drink cups. Number 7 is a kind of a catch all for any plastics that didn’t fit in categories one through 6. So, that can include biodegradable plastics, which can also contain toxic chemicals according to a study published in 2020. Number 7 also includes a group of plastics which can contain Bisphenol A, or BPA, which is a known endocrine disruptor. BPA was commonly in things like hard plastic water bottles, baby bottles, and sippy cups though public pressure has forced some companies to phase out BPA in their products. So, those are the chemicals of concern in plastic and generally how to avoid them. But that’s saying nothing about micro plastics that we unwittingly ingest.

And of course, less than 10 percent of plastic is recycled in this country.

So that means the vast majority is being incinerated, going in a landfill, or washing into rivers and ultimately the ocean. So, really it’s best to avoid disposable plastics as much as possible for many reasons.

CURWOOD: Indeed! And now in addition to generalized concerns we have fairly hard statistical evidence that demonstrates how death is associated with phthalates at least one age cohort.

BASCOMB: Hopefully more research will quantify the risks for everyone with enough rigor to get these toxins regulated and out of our environment.

CURWOOD: Alright, well thanks, Bobby, for looking into this.

BASCOMB: Sure thing, Steve.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb

Related link:

Find the peer reviewed NYU phthalate research article published in Environmental Pollution on October 12, 2021

[MUSIC: Chick Corea & Bela Fleck, “Brazil” on The Enchantment, by Ary Barroso, Concord Records]

CURWOOD: you can hear our program any time on our website or get an audio download. The address is LOE dot org that’s loe.org. There you’ll also find pictures and more information about our stories and we’d like to hear from you. You can reach us at comments@loe.org once again comments @loe.org our postal address is one again P.O. Box 990007 Boston, MA 02119. You can call our listener line anytime at 617-287-4121. That’s 617-287-4121.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Leonisa Ardizzone Quartet, “Autumn Leaves” on Afraid of Heights, by Kosma & Mercer/arr.Leonisa Ardizzone]

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote ®: The Tui of New Zealand

A tui perches on top of flax flowers. (Photo: © Christine Jacobson)

CURWOOD: We head now to New Zealand with this week’s Bird Note. Mary McCann reports.

BirdNote®

The Tui of New Zealand

[Tui song, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/171696, 0.07-.13]

The Tui is one of New Zealand’s most remarkable birds. It’s considered an intelligent bird on a level with parrots. And the foot-long Tui is a stunner, feathered in black with a blue iridescent sheen. A lacy white collar adorns its nape, and a distinctive white feather tuft puffs out from its neck like an ascot.

The Tui’s down-curved beak fits perfectly into native flowers, where it feeds on nectar while spreading pollen from flower to flower. Tui also eat native fruits and help disperse the seeds.

Tui aggressively defend their feeding territory of flowering trees from competing nectar-seekers. If a raptor threatens, Tui will fly quickly upward, then dive down on the unwelcome predator with whirring wings.

But the Tui is best known for its voice. Each Tui’s complex song is slightly different, a colorful mix of musical notes and offbeat sounds.

[Tui song, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/171696, 3.02-3.12]

A close-up of a tui. (Photo: Matt Binns, CC)

And the most surprising thing about that voice? Tui are one of only a handful of birds in the world that can imitate human speech, and they do it with a New Zealand accent.

[Tui whistling and talking, https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=tzPi_998Ghk, 0.01-.13]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Senior Producer: John Kessler

Production Manager: Allison Wilson

Producer: Mark Bramhill

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Digital Producer: Conor Gearin

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Tui ML 171696 recorded by S. Hill.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2021 BirdNote July 2021 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# tui-01-2021-07-20 tui-01

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/tui-new-zealand

CURWOOD: For pictures fly on over to the Living on Earth website. That’s LOE.org

Related link:

See more about this story on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Robert Plant and the Sensational Space Shifters, “Up On the Hollow Hill (Understanding Arthur)” on lullaby and…THE CEASELESS ROAR, by Plant/Adams/Baggott/Fuller/Tyson, Nonesuch]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Pulitzer Prize winning author Richard Powers on his new novel, Bewilderment. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and United

Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Charles Mingus, “Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting” on Something To Believe In, by Charles Mingus, Hear Music/Warner Special Products]

Bewilderment

Richard Powers’ “Bewilderment” follows a father, Theo, and his son, Robin, as they navigate environmental issues like a growing species extinction crisis, alongside personal concerns like the recent death of Theo’s wife and Robin’s neurodivergence. (Photo: Courtesy of Richard Powers)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Richard Powers, the author of the Pulitzer Prize winning novel “The Overstory” is back with a new science fiction book, “Bewilderment.” “The Overstory” was a sweeping exploration of our relationship with nature and the people who fight to save it. “Bewilderment” picks up on that theme at a much more intimate scale through the eyes of a father, Theo, and his son Robin. On an Earth a lot like our own but not quite the same, they stumble, bewildered, between crises. There’s the recent death of Theo’s wife and Robin’s mother and a growing species extinction crisis. And Robin has neurodivergence and erratic behavior. And these characters speak of their imperiled planet’s loneliness in the universe, a matter famously explored by physicist Enrico Fermi. Richard Powers joined us to discuss Bewilderment for our first Living on Earth Book Club event of Fall 2021. He explained that like Fermi, Theo is also a scientist who asks big questions of the universe.

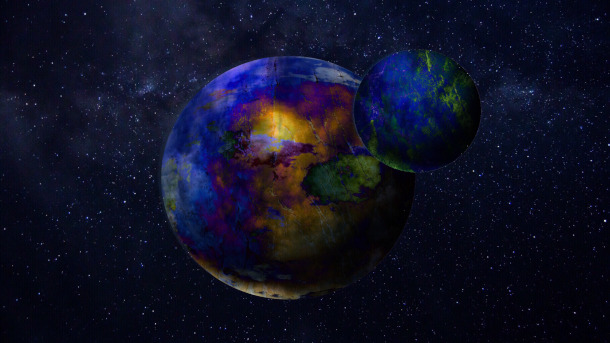

POWERS: In Bewilderment, the main story is about this troubled nine-year-old, and his father who's in his late 30s, who is an astrobiologist, and it's his father Theo's field astrobiology, that actually does get folded back into this personal narrative between the father and the son. That's the Powers part of this novel, the science part of this novel.

CURWOOD: Well, yeah, and of course, you have great fun, you know, stating the classic, you know, either we're completely alone, or there must be many of us. Although, actually, I think Enrico Fermi talked about this, the fact that we are here means that there must be more of us, because otherwise, we wouldn't be here at all.

POWERS: Yeah, there's a famous story about Fermi, I think he was out in Los Alamos in the early 50s, maybe 54, I think, and they were having lunch in the cafeteria and other colleagues of his were talking about, you know, the revolutions in astronomy that was showing that the universe is probably a good deal older, and a good deal larger than previously thought, which, you know, Fermi thought about for a while. And when he had sort of crunched the numbers a bit, he stopped and said, Then where is everybody, and this has come to be called the Fermi paradox. The numbers are sobering, the universe is three times older than the Earth, there are 100 billion galaxies, or more, each of those galaxies has on the order of 100 billion or more stars. And we now know that each of those stars is likely to have one or more planets. That's a lot of real estate, and a lot of time and, you know, it seems logical that we ought to be able to look up in all of that expanse, you know, having unfolded for all of that length of time and see some evidence of somebody else out there. But even with this great explosion of our ability to look and get fine details from very, very far away, this explosion of data over the last couple of decades, we are still confronted with what the people who think about the Fermi Paradox call the great silence.

CURWOOD: Well, yes. But isn't it a little bit arrogant, though, for us humans to think that we would even know about all of this, when I reflect on this, I think of you know, bees, they're greatly organizing in a social colony. And yet a bee would have no idea about this technology that you and I are using to talk to each other now, computers and all that. So just because we don't get it as humans, you know, maybe this all this connection is way above our pay grade. Richard, you know, maybe it's just.. [LAUGH]

POWERS: Well, there are two aspects to the the Fermi paradox. One is the one that we leap immediately to, which is where are the intelligent civilizations? And why aren't we getting signals? Why don't we see von Neumann replicating machines flying around the solar system? Why don't we see Dyson spheres, you know, advanced civilizations that have turned their stars into, you know, completely efficient solar cells? Well, that's one question. And certainly the search for intelligent life is always going to get the headlines. But astrobiology as a discipline, and it's still a very young discipline is probably more concerned with this larger question of life in aggregate, what are its affordances? What are its capacities? How easy or difficult is Abia Genesis, the beginning of life on a planet? What are the ranges of tolerance of life in the discovery of extremophiles on Earth has greatly broadened that envelope. Still, what Theo was looking for in the story is not intelligent life. He is developing computer models, to spectroscopy on the light coming through a planet's atmosphere. And looking at those spectra, looking for the fingerprints, the bio signatures for kinds of life that are probably microbial, they may be like ours, but they may have different kinds of chemical metabolic pathways. And just looking at every possible way that we would be able to look at an atmosphere and say, that planet is no longer restricted to merely physics and chemistry. That planet is alive, it has a biosphere. And that would be a revolution. You know, for us to discover that that would be a milestone in terrestrial human history. And it would change the way that we think about ourselves, even if it were only microbial life.

In Bewilderment there are questions about alien life on fictional planets juxtaposed with a dystopian image of a country falling apart. (Photo: lforce, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about your characters. You have Theo, his son, Robin. Robin is nine which you pick the person who hits just right that sweet spot of latency, right? They're really able to reason. The hormones haven't driven them crazy yet.

POWERS: There's still a tenderness and vulnerability of early childhood. And they're just about to go into that tumble of pre-adolescence. So Robin's mother has died about two years before the start of the story. And Theo knows that he's in over his head, he doesn't know how to deal with this boy whose behavior is increasingly volatile, you know, all he knows is that he loves the boys so much that he would do anything in his power to protect them from the world, but he doesn't know what that is. And he will not lie to the boy. And part of the trauma, of course, is personal, the loss of the mother at an early age, you know, may be enough to account for the wildest kind of behavior. But part as the story goes on, is caused by Robin, who, like so many children is kind of a pantheist or animist, you know, just sees the sacred and everything that's alive, you know, E.O. Wilson's biophilia is still going full tilt in this boy. And he is beginning to learn about this mass extinction that we've leveled on the earth. And it's a reality so devastating to him that he, you know, turns his anger and confusion and hostility outwards onto his father and not to the humans around him.

CURWOOD: What's your experience with children? By the way, Richard, do you have your own? Are you close to someone this age?

POWERS: I have a lot of experience having been a child for probably too much too long. And I have many nieces and nephews, both you know blood and by marriage. I do not have children myself. But I feel as if on at least three occasions, I've had a kind of surrogate parent relationship to children who have been in trouble with the world in one way or another, or whose behavior has pushed them outside of the media and on a normal distribution curve. And those were the kids that I was channeling when I tried to figure out who Robbie was and how he worked. And I have to confess that I think that the deeper I got into creating Robbie, the more I realized that I was drawing on my own sense of differences as a child. So it was a process of self discovery too for me to write the book.

CURWOOD: Wow. So when did you discover that this planet we call home is really in terms of the species that we know and love, including us is in a lot of trouble?

POWERS: Yeah, I asked myself that question. You know, what age that really become conscious of what kind of cataclysm we're facing down? And I do think that the first inklings -- you know, I was born in 1957. And so let me put that as one bookend on, you know, trying to locate my own childlike understanding of the environmental crisis. On the other end of that bookend, I'll put my second novel where I actually address global warming and climate change fairly early on for American fiction. That novel appeared in 1988. And while the scientists, of course, had been trying to make the case and bring the reality in front of the American public for years before that, you know, literary arts, obviously, were lagging in thinking of that, or using it as a meaningful component of a narrative. I do remember the first Earth Day very vividly in 1970. And so I would have been 13. And I guess that's somewhere in that window, you know, somewhere probably in my early teens, I began to take on that sense of dread that we all live with in one way or another, and we adults get very good at shunting it off and finding ways to whittle it away. But children don't do that. And I think that Robin's eco-trauma in bewilderment is very representative, even though he may be a, you know, a neurodivergent child, that element of his sensibility, the real despair and the real bewilderment that he feels in the face of the diminishment of the Earth is very representative of young people. And everything from my anecdotal experience to very recent polling shows that we have an epidemic of eco anxiety on the part of the young.

“Bewilderment” means to be perplexed or confused, and comes from a root word meaning “wilderness”. In his novel, Richard Powers seamlessly weaves together these sentiments. (Photo: Steve Jurvetson, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So without saying too much about what's in the book. What's amazing about your book, Richard is as you go to the hardest thing about the ecological disaster we're facing by dealing with feelings, by going to the emotion, you know, there's no recitation of facts here, or sort of cold reality of things. It's very much an exploration of feelings of how emotions work with us and among us, how they can even in some senses be shared. Wow, that's a pretty deep dive.

POWERS: You know, there was a line in my previous novel, The Overstory. All the best arguments in the world won't change a person's mind. The only thing that will do that is a good story. And I do think that reflects something about the way that our consciousness is structured, we have enormous capacity for empathy, for imagining ourselves into another person's life. But generally, through this technique of storytelling, and narrative, you know, we identify with the character in a story and we say, Who would I have to be to feel that way? And what would my life look like from that perspective? People change their world views, or they change their allegiance to convictions, not through being argued out of them, not through tables, and graphs, and charts. But through something in some invitation to imagine themselves in another circumstance, or through another lens, or from another perspective. And that's why the story is so devoid of the usual kinds of approaches to the climate crisis to the extinction crisis. It's just a dad and his kid. And you can choose, you know, as a reader, you can say, I remember, being a child like that and being frightened or believing in the sacredness of life, you know, the more than human life. Or you can say, holy cow, that dad, he is in trouble, because you cannot turn away from a nine year olds question and what I say to that kid, if the kid was asking me. And all of those acts of empathy, I think, are kind of end around on getting the reader engaged again, in a set of concerns that most of us have learned how to put the damper on.

CURWOOD: So taking it deeper, when you started to create these characters, and gave them through a little bit of sci fi, this fluency and emotional sharing. What did it change for you?

POWERS: How did I change in the act of writing the book? Yeah. Now that's, that's a good question. Wow. I wrote this book over a relatively short period of time during the pandemic. And there was a kind of psychotherapy for me in recreating myself, both as the son and as the Father, and living these roads lives not taken. And there was also a strange, cathartic pleasure in trying to create a hypothetical earth that looked a lot like the earth that we were living through under the Trump administration, but diverge from it in some significant ways, which I think was just simply therapy, you know, cast yourself back a year, year and a half. And think of how crazy it was day to day, what is going to happen? How far can we go? Where is this country going to land and, you know, hitting the refresh button button on your news feed, you know, three, four, or five times an hour or more, that was the world that created this book. It's a short book, and it's entirely narrated by the Father, and it's restricted to these two main characters. But it's a book that very intensely tries to grab something of the anxiety of the Zeitgeist circa 2020.

CURWOOD: Yet part of the Zeitgeist is social media or something that I'm more and more beginning to call anti social media, or its dark side, right?

POWERS: Have you seen that a lot of people are just starting to call it social, you know, they'll leave out the media and just say, you know, oh, I saw that on social which is pretty scary.

CURWOOD: As if it's real. So again, without any spoilers here. To what extent was that a device and to what extent does that reflect your feelings about what's going on in the way that we communicate these days?

Richard Powers is an American novelist whose works explore the effects of modern science, technology and climate change. (Photo: Courtesy of Richard Powers)

POWERS: Well, of course, during lockdown, I think that trend that had already been accelerating, that had us all disappearing into the virtual was just kicked up. So you know, an order of magnitude almost overnight, because that was for a lot of people, the only social contact that they had. And so I think some of the anxiety and part of the deranged quality of society that the book explores, as social media explodes on this boy and turns him into an unwilling celebrity, was simply responding to the kind of claustrophobia of the moment and, you know, feeling that we were now kind of disappearing into this simulacrum of social interaction. But my larger preoccupation in bewilderment is with something for which social media might be considered a symptom. And it is a cultural malady that I've taken to calling human exceptionalism. That's not my term, it's just a term that I've seen around. And it seems to be a good umbrella descriptor of this belief that we humans are somehow autonomous elements. And that the rest of the world is a resource for our program. And our program basically, is to further our control and mastery over the physical world over time and space over all the limitations posed to our conscious will. And the rest of creation is almost immaterial. We are the only interesting game in town. And it's that vision of human separatism that The Overstory challenges and that Bewilderment challenges.

CURWOOD: Wow, we'll wrap up with this question from a listener. Who is your ideal reader?

POWERS: Someone omnivorously curious. Who has a hunger for understanding his or herself, not only as a psychological creature bumping up against other human beings, but as part of all kinds of systems, and who wants to hear and think about and live in stories that try to reconnect the human to all of these larger, smaller stories above beyond alongside the human and bring us back to a living planet, as opposed to one that we've invented out of our private psychologies.

CURWOOD: Richard Power's new book is called Bewilderment. And thank you so much for taking the time with us tonight.

POWERS: Thanks for having me on the show. It's a fun conversation.

Related links:

- Learn more about Richard Powers

- Find the book "Bewilderment" (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Yo-Yo Ma & the Silk Road Ensemble (featuring Bill Frisell), “If You Shall Return” on Sing Me Home, Sony Music Entertainment]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Genevieve Santilli, Gabriell Urton, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth