October 8, 2021

Air Date: October 8, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

“Land Back” for Indigenous Peoples

View the page for this story

For Indigenous People’s Day we take a look at the “Land Back” movement that seeks to return land to its original inhabitants in North America or at least restore meaningful connections to those lands. To start, some Native Americans are campaigning for the return of the sacred lands of the Black Hills or “Hesapa” in South Dakota, which include Mount Rushmore. Krystal Two Bulls, Director of the Land Back Campaign at NDN Collective, speaks with Host Bobby Bascomb about the significance of the area and why “Land Back” aims to benefit all peoples. (07:34)

National Monuments Restored

View the page for this story

President Biden has restored the Northeast Canyons and Sea Mounts, Grand Staircase-Escalante, and Bears Ears National Monuments, reversing orders of former President Trump. The lapse in protection for the Bears Ears area had especially led to an increase in vandalism and looting. Executive Director of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition Patrick Gonzales-Rogers explains to Host Bobby Bascomb how lands are more than just historical sites for native peoples, and how they are key to their cultures, their spirituality, and their being. (04:53)

BirdNote®: Birds on the Polar Bears’ Menu

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

The Arctic is warming and changing fast, from vanishing sea ice and shifting habitats to what’s on the menu for the region’s top predator. BirdNote®’s Michael Stein reports. (01:52)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra fills in Host Bobby Bascomb about a study indicating the continuing prevalence of lead, a neurotoxin, in the blood of young children, though levels are lower than in years past. Also, some commercial baby foods can contain lead and other heavy metals like cadmium, mercury, and arsenic, though the FDA has yet to set standards. In the history calendar, the classic novel by Herman Melville Moby-Dick turns 170. (05:01)

Warming Arctic Creating “Pizzly Bear” Hybrids

View the page for this story

With the changing climate, polar bears are moving south in search of food, and grizzly bears are moving north in search of cooler climes. In some cases, the two have mated and created a hybrid animal known as a "pizzly" bear. Paleontologist Larisa DeSantis joins Host Bobby Bascomb to explain more about these hybrid creatures. (08:18)

Wasting a Wetland with Trash Ash

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

In the 1950s and ‘60s landfills were often sited in wetlands, land too soggy for farming or houses. That use would be illegal in the US today and many have been shut down. But the Massachusetts Department of Environmental protection still gave the green light to uncap part of a waste incinerator landfill in an estuary north of Boston and add half a million more tons of toxic ash. Host Bobby Bascomb reprises this story originally broadcast in 2018. (12:17)

Rising Seas Threaten Landfills

View the page for this story

Landfills in America were often sited in coastal wetlands before their value as wildlife habitat and buffers from coastal storms was better known. Now rising seas are threatening to unleash the trash, toxics, and even nuclear waste these landfills contain. Journalist Dave Lindorff joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss the risks. (06:44)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Krystal Two Bulls, Larisa DeSantis, Dave Lindorff, Patrick Gonzales-Rogers

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

At this Indigenous Peoples Day we take a look at the land back movement, for Native Americans to reclaim their ancestral land.

TWO BULLS: Not only are we fighting to reclaim our relationship to the land but we’re also fighting because we know when we have relationship with the land and we’re the ones stewarding the land all people benefit. I think it’s somewhere around 20 percent of indigenous peoples manage 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity. We protect that.

BASCOMB: Also, the call for President Biden to restore Bears Ears National Monument.

GONZALES-ROGERS: The President himself said this was a first day issue. This was not a particular campaign or advocacy on our part, this is what the President campaigned. So it is his words that we rely on.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

“Land Back” for Indigenous Peoples

A Land Back flag flies under the US Flag outside Aitkin County Courthouse in Aitkin, Minnesota. (Photo: Laurie Shaull, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

This US holiday weekend has long been known as Columbus Day but is now celebrated by many as Indigenous Peoples Day. It’s a day to reflect on the legacy of first contact between Europeans and Native Americans. Columbus and his 1492 “discovery” kicked off a pattern of land theft and genocide that would sweep across the US fueled by a European perspective that the land and its people were their God-given right to claim and subdue. The entire region was once home to diverse native peoples, but today they hold just 2 percent of the land, an area about the size of Idaho. Now some native groups are calling for their tribal land to be given back to them. For more we called up Krystal Two Bulls, Director of the LANDBACK Campaign at NDN Collective. Krystal, welcome to Living on Earth!

TWO BULLS: Thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: So what exactly does "Land Back" mean for you?

Krystal Two Bulls speaking about Land Back at a ceremony in Hesapa, the Black Hills, on July 21, 2021. (Photo: courtesy of NDN Collective)

TWO BULLS: You know, Land Back means a lot of different things. But I would say first and foremost, Land Back is very much the literal reclamation of land. And it's the reclamation of everything stolen from us when we were forcibly removed from the lands. So we were fully thriving economies and societies that, you know, were fully functioning here before colonization. And so our kinship systems, our governance systems, our health care, housing, food, you know, education systems, all of these things were based on our relationship to the land. And more significantly, it's our spirituality, it's our culture, it's our language, and it's the ceremonies, all of which are very tied to the land as well. And so Land Back is reclaiming all of those things. And it's literally reclaiming the land, not in a colonial sense of, in terms of like ownership of the land, but using that as a tool to be able to get access to, to rebuild our relationship with the land, you know, and then that builds all of those things, right? And so yeah, like Land Back is literal reclamation of land. And I would say that also, you know, through the Land Back Campaign with NDN Collective, it's also very focused on public lands like federally managed lands and state public lands that were strategically removed from us and placed into like national park system or state parks, to specifically keep us from that land.

BASCOMB: Now, of course, the whole of the United States must have been native land before colonists came along, but it sounds like you want to start with public lands, and specifically, the Black Hills and Mount Rushmore. Can you tell us more about why that area is so special and that you want to begin this campaign there?

Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota’s Black Hills. The Lakota people believe that the Wind Cave is where their ancestors emerged from the earth. (Photo: Amanda Scheliga, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

TWO BULLS: Yeah, I mean, for us, the Black Hills, the He Sapa, you know, it was the traditional territory of many different nations, not just the Oceti Sakowin, but the Northern Cheyenne, and different nations all around the area. We came out of the earth there. Our stories tell us we came from these lands, to be the original stewards of these lands, to caretake and be in relationship with these lands. There's water here, our medicines are here, we can hunt here. There's different nuts and berries and fruits that we can gather that grow naturally here. So everything that we need to exist as a people is right here. And we are mandated to protect everything that is sacred, and that gives life. For us, that's what the Black Hills represent is, is a life source, and a connection to our very being as Lakota people. You know, for me, as an Oglala Lakota woman, as a Northern Cheyenne woman, to be connected to that is literally part of my identity. And the fight for the Black Hills has been ongoing since settlers first entered our territory. These are our traditional territories, and these are part of our actual lands, according to the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. And for us, Mount Rushmore is like the ultimate shrine to white supremacy. I mean, it was carved by a KKK member; everything about it represents white supremacy in the heart of this so-called nation. Calling attention to that is very significant. Not only is it us doing our duties, and our responsibility of protecting and caretaking this land that gives life, but also it's standing in solidarity and also addressing the fact that this nation was built on white supremacy, and that these systems continue to uphold it.

Mount Rushmore is a symbol of white supremacy for some Native Americans, with its depiction of four white male US presidents, including Washington and Jefferson who both owned African American slaves, and Theodore Roosevelt, who called for the removal of “the red man” from National Parks. It was carved by a sculptor with close ties to the KKK (Photo: Udo S, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, Krystal, what would it actually look like for land like Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills to be returned to Indigenous people? How would that work?

TWO BULLS: Yeah, I mean, there's so many ways that Land Back is happening right now. And specifically with the Black Hills, you know, it looks like land literally being returned to the Oceti Sakowin, and that includes Mount Rushmore. You know, that's just one example in terms of like federal, right and these federally managed lands, but I think there's so many stories of individuals returning land back to nations, or tribal members, or to native-led organizations. There's stories of nations able to purchase back pieces of land, and to be able to get them back in trust, and to be a land base for their community and their peoples. Land trusts are definitely an avenue for land reclamation to happen. There's land occupations, where different nations have treaty rights, and rights over these territories that were not honored by the United States government and that were broken. And so nations are occupying those lands and reclaiming them. Land Back can look many, many different ways. You know, and for us with the Black Hills, it does very much include those lands being returned back to the Oceti Sakowin, and being managed by us as well.

On July 3, 2020, just before former President Trump held an Independence Day event at Mount Rushmore, Indigenous land defenders blocked a major highway leading to the monument and called for the return of the Black Hills (Hesapa) to the Oceti Sakowin. (Photo: Willi White, NDN Collective)

BASCOMB: And if they were managed by you, would you still feel comfortable having tourists and visitors come to visit them as they do now?

TWO BULLS: I mean, I think those are like larger conversations that I can't really give a specific answer to, you know, because like that's not my right to say and speak on behalf of an entire Oceti Sakowin Nation. But what I will say about that is that, we are not here to replicate colonial systems and colonial practices. And so we do this work because we work on behalf of all peoples. Not only are we fighting to reclaim our relationship to the land, but we're also fighting because we know that when we have relationship with the land, and we are the ones stewarding the land, that all people benefit. I think it's somewhere around 20% of Indigenous peoples manage 80% of the world's biodiversity. And that is a huge number, we protect that.

Krystal Two Bulls is Oglala Lakota and Northern Cheyenne and directs the LANDBACK Campaign at NDN Collective (Photo: courtesy of Krystal Two Bulls and NDN Collective)

When we are fighting oil pipelines, because we know that they are going to leak and that they're going to pollute drinking water, we don't do that just for our communities. We do that for every community that is downstream from that pipeline that is going to get contaminated water. And for us to really look at mitigating climate change, and really investing in having a world that is inhabitable in the future, it has to start with Indigenous people. It has to be led by Indigenous people because we descend from those systems, those healthy systems and the healthy ideology that benefits and allows for all people to thrive, that creates healthy economies, that creates healthy societies. We know that it is possible because that is what we come from. So we're not here to replicate colonial systems of deporting people and kicking people out and treating people the way that we have been treat[ed]. We are here to show a different way forward. And that starts with us reclaiming land.

BASCOMB: Krystal Two Bulls is Director of the Land Back Campaign at NDN Collective. Krystal, thank you so much for taking this time today.

TWO BULLS: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Read the LANDBACK manifesto

- High Country News | “The battle for the Black Hills”

- The Washington Post | “The creator of Mount Rushmore’s forgotten ties to white supremacy”

- Read more about LANDBACK, climate justice, and Indigenous power with NDN Collective’s book “Required Reading”

- About Krystal Two Bulls

[MUSIC: Native American peace song (Ya he ya he)]

National Monuments Restored

Grand Gulch cliff art in Bears Ears. When the Bears Ears National Monument lost much of its protected status, Indigenous historical art like this was at risk of vandalism and degradation. (Photo: Courtesy of US Bureau of Land Management on Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: Activists cheered an October 7th announcement from the White House that President Biden would restore protection for three national monuments, each of which were shrunk or modified under the previous administration.

Many Republicans say Congress should make these decisions not just the President, so boundaries can be permanently settled.

The three in question are the Northeast Canyons and Seamount Marine National Monument, off the coast of New England and Mid Atlantic as well as Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears National Monument, both in Utah.

President Biden pledged to restore protections for the monuments on the campaign trail, a move welcomed by environmental groups and native nations though they were frustrated that it took the better part of a year to do so.

Native American nations were especially vocal about Bears Ears.

“House on Fire”, a Cedar Mesa cliff dwelling in Bears Ears National Monument where indigenous tribes once lived. (Photo: Courtesy of US Bureau of Land Management)

Native peoples have lived in the area known as Bears Ears for upwards of 13,000 years.

It’s considered sacred land by many Native Americans and home to thousands of archeological sites and ancient petroglyphs.

So, 5 nations of native peoples, each with deep ties to the land, petitioned President Obama to use the Antiquities Act to create Bears Ears National Monument in 2016.

Just a year later, President Trump shrank the size of the National Monument designation by roughly 85 percent, claiming it would boost economic development.

A wall filled with indigenous rock art is just some of the remarkable features of Bears Ears National Monument that need protecting. (Photo: Courtesy of US Bureau of Land Management on Flickr)

And in the absence of any protection many ancient archeological treasures there, including native burial sites and petroglyphs, have been damaged.

Patrick Gonzales-Rogers is the Executive Director of The Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, representing the 5 nations native to the region.

GONZALES-ROGERS: For some of the tribes, and there are five distinct ones, the Bears Ears in many instances, represents their particular church and cathedral. These are where cultural and spiritual practices are not just part of their history, this is a part of their contemporary state of being. I would really encourage people to think about it in the same way that you would think about a 300 year old Protestant chapel in rural Connecticut, or the Vatican, or the Cathedral of Notre Dames. These are iconic, these are inflection points, and they're the cornerstone of their actual theology.

Close up of indigenous rock art in Bears Ears. (Photo: Courtesy of US Bureau of Land Management on Flickr)

BASCOMB: I understand that Bears Ears is actually being damaged right now by visitors to the area.

GONZALES-ROGERS: Mainly the BLM and the US Forest Service have not added more resources, either in a people power sense, or assets. And so there is very little to manage this flow of people. We've already seen all kinds of graffiti, as well as destruction of cultural sites. Whether these are petroglyphs, potteries, or things of that nature, these become, you know, in some ways, the objective of visitors. Can I find these things? Can I take something home? Some are done with a kind of, what I would call, benevolent ignorance. Others are they want to actually destroy native things. And so this makes for, in some instances, irreparable harm.

Indian Creek in Bears Ears. (Photo: Courtesy of US Bureau of Land Management on Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: So just looking at a little bit of the history here, Bears Ears was established as a national monument under President Obama and then shrunk by roughly 85% under President Trump. Essentially, to pave the way for uranium mining there. To what degree is that kind of extraction still a possibility in Bears Ears?

GONZALES-ROGERS: So there is a backstory to this. And this backstory is a horrific one. Trump did this under the rhetoric of the proper usage of public lands for this regional area is to turn over to the extraction industry. And that would then buoy the regional economy. Well, a couple of things about that. And so again, let's be specific, it's uranium. You can't use the land for another 10,000 years after you use it for uranium. Two, as we speak, we have about a four decade surplus of uranium. All right. Third, uranium can be actually acquired 85 to 90%, cheaper in Canada, Australia, and the Ukraine. So that's the third point. The fourth point in which is the most egregious, the entity that most benefits from this is an entity called Energy Fuels, Inc. They are not a US company. They're a Canadian company, with outfits in Colorado. And they basically drew down the reduction boundaries, which the Trump administration followed almost verbatim.

US Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland speaking with stakeholders of Bears Ears in Utah. (Photo: Courtesy of US Bureau of Land Management on Flickr)

BASCOMB: Patrick Gonzales-Rogers is the Executive Director of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition. Patrick, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

GONZALES-ROGERS: My pleasure, time well spent.

Related links:

- Click here to read more about the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition’s Work

- High Country News | "Bears Ears is back -- but don't celebrate just yet"

BirdNote®: Birds on the Polar Bears’ Menu

A polar bear and a gull. Diminishing sea ice is leading to polar bears relying more on birds and their eggs for sustenance. (Photo: Cheryl Strahl)

[BIRD NOTE® THEME]

BASCOMB: The Arctic is warming and changing fast, from melting glaciers and shifting habitats to what’s on the menu for the region’s top predator. BirdNote’s Michael Stein has more.

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/birds-polar-bears-menu

BirdNote®

Birds on the Polar Bears’ Menu

STEIN: Polar bears, mighty predators of the Arctic, hunt seals and their pups on sea ice. But a warming Arctic means longer seasons without ice and the early return of polar bears to land. Their untimely arrival coincides with droves of birds sitting on a bounty of eggs.

[Cacophony of Thick-billed Murres, https://www.xeno-canto.org/141228, 0.05-.11]

Depending on where a polar bear is in the Arctic, there may be Common Eiders, Thick-billed Murres (pron. murz, like purrs), Little Auks, Glaucous Gulls, Lesser Snow Geese and Barnacle Geese on the menu. While bears feed primarily on eggs and chicks, they will take the occasional adult if they can grab one.

[Alarm call of a female eider with chicks, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/279182411, 0.02-.11]

Unfortunately, a single clutch of eggs is no substitute for a seal rich in fat. So, hungry polar bears go from one nest to another, and then another, until they’ve eaten their way through pretty much all of the nests in a colony.

The fate of these birds is unknown, but at least one bird is getting some help. On Cooper Island, off the coast of Alaska, where nesting Black Guillemots (pron. GILL-uh-mahtz) are vulnerable to predation, scientists have placed polar bear-proof nest cases to give the birds a fighting chance.

BASCOMB: For photos, head over to the Living on Earth Website, Loe dot org

[Black Guillemot chick squeaking, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/174688311, 0.01-.04]

###

Written by: Richa Malhotra

Senior Producer: John Kessler

Production Manager: Allison Wilson

Producer: Mark Bramhill

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Digital Producer: Conor Gearin

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Thick-billed Murre Xeno Canto 141228 recorded by A. Spencer, Common Eider ML 279182411 recorded by A. Spencer, and Black Guillemot ML 174688311 recorded by P. Davis.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2021 BirdNote July 2021 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# polarbear-01-2021-07-22 polarbear-01

References:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2020.11.009

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00300-010-0791-2

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/birds-polar-bears-menu

Related links:

- Find this story and more on the BirdNote® website

- New Scientist | “Polar bears shift from seals to bird eggs as Arctic ice melts”

[MUSIC: Native American peace song (Ya he ya he)]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Grizzly bears are moving into the warming Arctic and mating with polar bears to create …. Pizzly bears. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Duke Ellington, “Very Special – Remastered” on Money Jungle, Blue Note Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Lead exposure in young children can lead to a host of health issues, particularly affecting the brain and nervous system. (Photo: Nenad Stojkovic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, it's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with environmental health news. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby, we have maybe the classic modern American tale. Half of young American kids tested in a sweeping study, 1.1 million kids younger than the age of six, had some level of lead in their blood, according to a peer reviewed piece in the journal JAMA Pediatrics.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's pretty troubling. I mean, lead in the blood for children especially can lead to a whole host of long term health problems, including learning disabilities.

DYKSTRA: It’s a classic neurotoxin. It's everywhere, although not as everywhere as it used to be bear in mind. 50 years ago, we phased out lead fuel, kids' lead levels have dropped accordingly. But they're far from done.

BASCOMB: I believe, also, we really have to worry about old water pipes and things that can deliver a lead right into your glass of water for children.

DYKSTRA: That’s correct. And that's the main culprit, particularly in older cities. Flint, Michigan is kind of the poster child for lead pipes leading from a watermain into individual homes. That is also a target removing lead pipes of any infrastructure bill. However, whatever whenever it may pass.

BASCOMB: Right? Well, the CDC standards indicate that just 2% of kids have concerning levels of lead in their blood. But most public health officials will tell you that there's no such thing as a safe level of lead for children.

DYKSTRA: That’s correct. And those lead levels are neurotoxins at very minute levels. A second story about neurotoxins, including lead on economic and consumer policy is going after the FDA the Food and Drug Administration to speed up its work in setting standards for heavy metals in baby food products.

Some commercial baby foods can contain heavy metals including lead, mercury, and cadmium (Photo: Brian Brodeur, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: Baby Food, gosh, I guess I mean, it's surprising. On the one hand, you would think well, of course there shouldn't be heavy metals in baby food. It goes without saying right. But if there's no standards, then companies have nothing to work with.

DYKSTRA: Right. And the levels of concern just like lead in drinking water or elsewhere, are absolutely minute. The neurotoxins include not only lead, but things like cadmium and mercury and arsenic. They're concerned about big traditional names of cereals, as well as some cereals sold as organics, because some of these substances are in baby food and other food products naturally.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's really troubling. And so they researchers are finding this just across the board, heavy metals in baby food.

DYKSTRA: Across the board. There are no safe levels for things like cadmium and mercury in baby food products. So this is something that Congress is urging the Food and Drug Administration to take a very close look at, and set very tight standards.

BASCOMB: And in absence of those standards, right now, I wonder if companies are moving forward on their own to make sure that their product is safe for children for babies?

DYKSTRA: Well, they're certainly paying attention. It's not always easy to get companies to regulate. But when you talk about children's health, and things like baby food products, it's impossible to ignore.

BASCOMB: Yeah, and that's a publicity nightmare for a company if they think parents don't think their product is safe anymore. Well, what do you have for us from the history books this week, Peter?

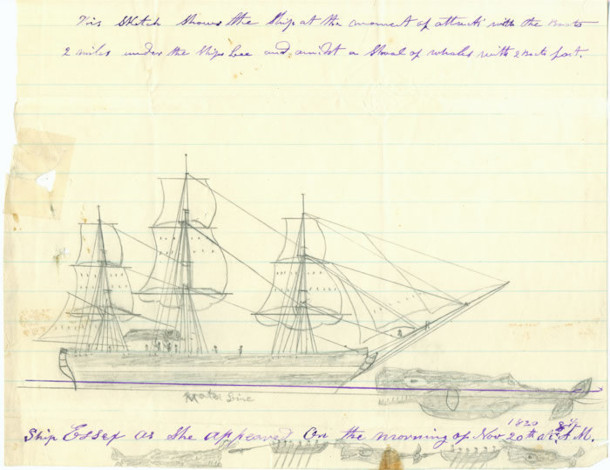

DYKSTRA: Well we talked about an epic tale of infrastructure. How about an epic tale that sometimes considered the great American novel? This time of year in 1851, Herman Melville's, Moby Dick was published initially in London, and even though it's fiction, it's based on a real life Episode whaleship ethics was actually rammed by a sperm whale in 1820. The ship was pretty much destroyed between that and a storm. The crew scattered throughout the South Pacific, and later came together to tell their tale, which was fictionalized told, retold, miss told, and by 1851, we ended up with Moby Dick.

A sketch representation of a whale striking the whaleship Essex on November 20, 1820. The sketch was done by cabin boy Thomas Nickerson after his rescue. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Wow. 1851. So 170 years later, and the tale of Moby Dick still resonates with people.

DYKSTRA: It’s a pretty potent one, particularly when you consider that Captain Ahab is a 19th century clinical example of obsessive compulsive disorder.

BASCOMB: I guess that's true. All right. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Thanks a lot, Peter. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there’s more on these stories on the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- Vice | “Half of Young, American Kids Have Lead in Their Blood, Study Finds”

- Politico | “Congressional Panel Slams More Baby Food Brands Over Heavy Metals”

- Learn more about the publishing of Moby Dick

[MUSIC: Caamp, “Send the Fisherman” on Boys (Side B)]

Warming Arctic Creating “Pizzly Bear” Hybrids

Pizzly bears have a physical appearance that is a mix of grizzly and polar bears. (Photo: Philippe Clement/Getty Images)

BASCOMB: The Arctic is warming faster than any other region on earth, it actually rained on the Greenland ice sheet in August for the first time ever. And sea ice recently reached its minimum extent for 2021. It was the 12th lowest amount of ice since scientists began keeping records. And for the endangered polar bear, a warming Arctic is bad news. With their habitat melting, polar bears are having trouble finding food. At the same time grizzly bears are moving north and, in some cases, mating with polar bears, creating a hybrid animal known as a pizzly bear. Larisa DeSantis is a paleontologist and associate professor of biology who studies pizzly bears at Vanderbilt University. She joins us now for more. Professor DeSantis, welcome to Living on Earth!

DESANTIS: Thanks so much for having me.

BASCOMB: So tell me please, what does a pizzly bear look like? And how do these hybrids compare with the parent species of grizzly and polar bears?

Dr. Larisa DeSantis molding teeth from polar bear jaws from the University of Alaska Museum of the North. (Courtesy of Larisa DeSantis)

DESANTIS: So a pizzly bear is essentially an intermediate between these two. It's a hybrid species, and it's actually fertile. And they actually look exactly like you would expect mixing a polar bear and a grizzly bear. So, polar bears tend to have really elongated skulls. And this is because they're really well suited for being able to hunt seals in sea ice. And so essentially, they can sort of get into those holes and effectively hunt those seals. The grizzlies have much shorter skulls, and they're able to exude really high bite forces to be able to eat really hard foods when needed. And so essentially, this pizzly is intermediate between those two, you can also see that their coloration is sort of intermediate, right? So they're, they're a bit lighter in coloration than a grizzly, but darker in coloration than a polar bear. And there's lots of other features that folks have studied in captivity, that seems to also be intermediate as well. And this includes sort of the morphology of their hair to also their swimming ability, right? So they're better swimmers than grizzlies, not as good as polar bears. Now, typically, hybrids are not better suited than either parent species for a particular environment. Normally, we would say that a grizzly bear is better suited for its environment, and a polar bear is better suited for its environment. But as we're dealing with a warming Arctic, we really don't know how these pizzlies will do in the future, and they may be better suited for the warming Arctic than the polar bear.

BASCOMB: Now, many hybrid species like ligers, or mules are sterile and can't produce offspring themselves. But I think you just said that pizzly bears actually can reproduce. Does that make them their own species?

DESANTIS: So I teach introductory biology. And there we go over the different species concepts. And typically, as biologists, we use the biological species concept. And what that idea is about is essentially that if two different species are able to produce fertile hybrids, then technically they are not two different species. Now, that being said, the polar bear and the grizzly bear are really sort of a unique situation. They diverged roughly around 500,000 or 600,000 years ago. They're pretty closely related to one another in the grand scheme of things. And they also look quite different from one another, right? These are different bears, we know they're different species. They do completely different things in their ecosystems. They're of different ecological niches, for example. And so if we looked at, say, even the morphological species concept, or the ecological species concept, we would definitively say that these are two different species. But you're absolutely right, you know, they can produce these fertile hybrids, that's really interesting. And we know that it's actually able to persist. So for example, there was a study in 2017, where they noted a particular bear was the product of a pizzly-grizzly mating. And so a polar bear and a grizzly had made it. Then that offspring, the pizzly mated with another grizzly and produced another hybrid. And so we do know that you can still get sort of the viability of these bears sort of down the road.

Archaeological polar bear specimen from ~1000 years ago, during the Medieval Warm Period (left) and modern polar bear from the 20th century (right). (Photo: Scott Shirar)

BASCOMB: So then would you say pizzly bears are their own species?

DESANTIS: I wouldn't go that far. They are a hybrid. And hybrids occur pretty frequently in nature. And typically we see hybridization occurring, you know, over and over and over in particular regions where two different species are coming together. And so it's not surprising that we see hybrids of these two bears, especially since they're closely related. And this is because essentially, the brown bears, the grizzly bears are moving north due to Arctic warming. The polar bears are actually having to retreat from the sea ice, the lack of sea ice, and they're having to come further inland and often travel further south or look for other food resources. And other studies are coming out even, you know, just recently showing that they're trying to eat you know, seabird eggs and not very effectively or, you know, whatever they can sort of scrounge around and and that's one of the things that is really kind of challenging for this polar bear is because it has this elongated skull, it's not well suited to eating just sort of any type of food source, right? It actually has biomechanical constraints that prevent it from, you know, eating really hard things. And so it's sort of having to scavenge potentially, to find different food resources. It'll find these bowhead whale carcass sites, that's where the grizzly bears can also be as well. And they're coming into increased contact and occasionally mating.

BASCOMB: So how many pizzly bears are there now roughly, would you say, and what is the trend looking like for the populations going forward?

DESANTIS: So that's a great question. And unfortunately, we don't know the answer. We don't know how many pizzlies there are. The pizzly was first discovered in 2006 and has recently been you know the focus of various studies both in captivity, and also in the wild to try to sort of document occurrences when we have hybridization. It can be difficult to sometimes tell if morphology isn't quite signaling that this is a hybrid species. But in many cases, these bears do really look intermediate in form and can be identified visually and then subsequently followed up with genetic testing to sort of see if they are, in fact hybrids and verify this. So we don't know if if hybridization will continue, will increase, will decline. I expect that it will increase because we are increasing the frequency that these two bears are coming together. That all being said, it's something that needs to be sort of monitored carefully. And we really need to better understand sort of how fit or or not fit these hybrids are for living in a sort of Arctic ecosystem, but also a dynamic and changing ecosystem.

Dr. Larisa DeSantis at the University of Alaska Museum of the North. (Courtesy of Larisa DeSantis)

BASCOMB: So with polar bear populations declining so dramatically with the loss of sea ice, and with climate change, as you were just saying, how likely is it that they will ultimately be replaced by pizzly bears or even grizzly bears if it gets much, much warmer? And for that matter, how would a different apex predator in the Arctic affect the whole ecosystem?

DESANTIS: So that's a fantastic question. And we really don't know the answer to that. But what we need to do is actually monitor the polar bears, continue to monitor grizzlies, and also monitor these pizzlies, and see how they do. So as I mentioned, hybrids normally aren't better suited than either parent species, right? But in this case, with the environment changing, they may be our hope for an Arctic bear. And what we do know about predators across the globe, and through time is that apex predators especially are really key to the functioning of ecosystems, right. This is why wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone, because the elk populations were sort of out of control, wreaking havoc on the vegetation, things were out of balance. And so reintroducing wolves to that system really helped provide sort of a more functional ecosystem and a more stable ecosystem. So we know that the apex predators are super important. I'm really hopeful that we can change some of our actions in regards to the polar bear and give that species hope. That being said, if this pizzly, this sort of intermediate morphology, intermediate conditions is better suited, which we don't know. But if it is, then that may give us hope for an Arctic bear in a world in which we have Arctic warming.

BASCOMB: Larisa DeSantis is a paleontologist and professor at Vanderbilt University. Larisa, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

DESANTIS: Thanks so much for having me. This is really fun.

Related links:

- The Independent | “‘Pizzly Bear’ Hybrid Could Soon Become ‘More Common’ Due to Global Warming”

- Read Dr. DeSantis’ study about how the changing climate affects polar bear habits and physiology

[MUSIC: Caamp, “Great Heights” on Caamp]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Sea level rise poses a serious risk for coastal landfills. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Arturo Sandoval , “Blues En Fa” on My Passion For The Piano, Written By Arturo Sandova, Columbia]

Wasting a Wetland with Trash Ash

The Wheelabrator Saugus waste-to-energy plant. (Photo: Fletcher6, Wikimedia

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Around the country thousands of coastal landfills are threatened by sea level rise and storms. Decades ago, wetlands were seen as a good place to dump trash, since they were considered useless for housing or farming. Now we better understand how critical wetlands are as a wildlife habitat and buffers from coastal storms. We’ll have more on the big picture risk of sea level on coastal landfills a bit later in the show but first let’s look back at a story about one of the one thousand waste incinerator landfills across the country. Waste incinerators generate toxic fly ash and wouldn’t be allowed in coastal landfills today. But many have been grandfathered in, including a 1950’s landfill in Saugus, Massachusetts, slated for closure in 1996, but still operating. In fact, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection gave the green light to allow an additional half million tons of carcinogenic fly ash and bottom ash to be dumped there by a company known then as Wheelabrator. It’s a leaky unlined landfill, sitting in an estuary, in an area prone to flooding. I reported on the facility back in 2018, just as a Nor’Easter arrived on a full moon to dump torrential rains on the coast just north of Boston. Each high tide brought a new round of flooding for residents like Kelly Lampedecchio who shared videos of her flooded neighborhood on Facebook.

[SOUNDS OF SPLASHING WIND AND RAIN]

LAMPEDECCHIO: Ok, we’re at high tide.

The Wheelabrator Saugus waste incinerator and landfill are located inside the Rumney Marsh Reservation, near the Atlantic Ocean. (Image: Google Maps)

BASCOMB: The water is ankle deep in her backyard. Out front, the street is completely submerged and water creeps up the front steps towards her door. Every house on the street is sitting in water.

LAMPEDECCHIO: The guardrail is completely gone. That’s a dock that floated over from the boatyard. The neighborhood has totally disappeared.

BASCOMB: It’s a lot of water but Sandra Hurly Jewkes and other residents of Revere say they are used to flooding here.

JEWKES: When we get a flood tide here this house becomes an island. It happens, I’m going to say, 5-7 times a year.

BASCOMB: Sandra called me during the storm from her mom’s house, which sits on a narrow spit of land between Rumney Marsh and Massachusetts Bay – the Atlantic Ocean. She says three generations of her family have lived here, in the house her grandfather built.

JEWKES: It’s a beautiful estuary. We have all kinds of birds that nest here. We have turtles, we have seals that come in the river. I mean, it’s beachfront property, it just comes with the downfall of having a trash incinerator across the street.

BASCOMB: That trash incinerator – and the landfill next to it – belong to a company named Wheelabrator Technologies. They own more than a dozen waste facilities across the country.

JEWKES: When the tide comes in and we get these flood tides the landfill and Wheelabrator become an island also, they are cut off from land. It’s water on both sides. So the water is literally lapping right up on the landfill itself.

Part of the Wheelabrator Saugus waste incinerator. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: And it’s the landfill that really concerns local residents like Sandra. It’s the repository for fly ash and bottom ash – that’s the material that doesn’t actually burn up during waste incineration. It contains a cocktail of heavy metals and toxic chemicals – mercury, cadmium, arsenic, lead, and dioxins. For every 4 tons of trash burned, 1 ton of ash is left behind and it has to go somewhere.

[AMBIENT SOUND OF WAVES, PLANES OVERHEAD]

BASCOMB: Elaine Hurley, Sandra’s mother, stands in a restaurant parking lot in Revere overlooking the landfill. Revere and the surrounding cities are working class, industrial communities. Elaine says she remembers back before there were scrubbers on the incinerator when all the toxic chemicals went out the smoke stack and straight into the air, a stone’s throw from her home.

HURLEY: When they started burning the fly ash would come in my house. On the windowsill it was like a black soot all the time and you run your finger it was like greasy. It actually ate the paint off the side of my car that was parked towards it.

BASCOMB: Elaine Hurley says she’s relieved to have cleaner air but concerned about what the chemicals that ate the paint off her car could do to the marsh if they leach out of the landfill.

HURLEY: We’ve gone over there, we’ve videotaped the marsh where the water leaches out. No vegetation. It’s all dead. So, what’s the affects on the fish? You know? What’s the affects on the ducks?

BASCOMB: The landfill sits literally inside the Rumney Marsh, which was declared an area of critical environmental concern in 1988. It’s a vitally important habitat for local and migrating species – an oasis in an industrial area. Planes leaving Logan airport fly over every two to three minutes. A busy highway borders the estuary on one side and it’s surrounded by development on the other sides – houses, gas stations, dry cleaners and so on.

Joan LeBlanc of the Saugus River Watershed Council stands behind a Dunkin’ Donuts next to a pile of lobster traps and looks out at the estuary.

[SOUNDS OF SEA GULLS AND TRAFFIC]

LEBLANC: In the spring when the fish come in, the rainbow smelt, alewives and all sorts of other fish come in from the ocean to feed and to migrate. In the summer time you’re going to see all manner of shore birds as well as migrating birds so great blue herons, snowy egrets. There are also mammals; you have river otters, you have musk, coyotes even sometimes.

BASCOMB: She says any chemical contaminants in the marsh will bioaccumulate up the food chain to eventually contaminate more species, including humans that eat fish.

LEBLANC: These are the type of issues that keep me up at night.

BASCOMB: Research suggests that by the end of the century there will be one and a half to two feet of sea level rise in this area. Joan LeBlanc says sea level rise coupled with frequent coastal storms makes the incinerator landfill particularly vulnerable.

LEBLANC: So, yes we are really concerned about the future. And if there were some kind of major breach in a storm here with this ash landfill and that were to empty into the marsh, I just don’t know how or if you would be able to clean that up.

Located in an industrial community, the Rumney Marsh is designated an area of critical environmental concern. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Most of the landfill is currently capped and from afar looks like a grassy hill, there’s even a bird sanctuary on part of it. But the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection gave the green light for Wheelabrator to tear the cap off 39 acres of the facility, so they can dump roughly half a million tons of additional incinerator waste into two valleys originally designed for storm water runoff.

Kirstie Pecchi is director of the zero waste project with Conservation Law Foundation. She says the MassDEP decision to expand the capacity of the landfill is especially egregious because the landfill doesn’t have a plastic liner.

PECCI: Here there just happens to be clay because when you dig a hole in a marsh you’re going to hit clay. There was not a clay liner constructed as far as I can tell, ever.

BASCOMB: The landfill, built in the 1950s, pre-dates the federal law that requires such facilities to have a proper plastic liner. But Pecci says even if this facility did have a plastic liner it would likely still leak.

PECCI: Because the waste is caustic. That’s going to eat through a plastic liner or poke through sooner or later. So even if this were plastic lined I’d say we need to be testing what’s escaping the landfill.

BASCOMB: And that’s another controversial point. This is the only incinerator landfill in Massachusetts where the state does not routinely sample groundwater as required by federal law. Pecci, of the Conservation Law Foundation, says Wheelabrator’s own graphs show that the bottom of the landfill is actually resting in water.

PECCI: So, there’s no way to keep the contamination from entering the marsh because it’s in the water. By definition it’s going to spread through the water.

BASCOMB: To find out why they aren’t testing the ground water as the law requires I made many requests to speak to Wheelabrator Facilities, the Massachusetts governor’s office, and the Massachusetts DEP, Department of Environmental Protection. They all turned me down. The DEP suggested I talk to the Environmental Protection Agency region 1, which overseas Massachusetts. But the EPA referred me back to the MASS DEP.

Kirstie Pecci of the Conservation Law Foundation speaks to a group of reporters and residents just across the marsh from the Wheelabrator facility. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

In an e-mail, Ed Coletta, a spokesman for MassDEP, explained that instead of taking water samples near the facility they rely on a slurry wall to contain the landfill. They measure the pressure both inside and outside the wall with an instrument called a piezometer. As long as the pressure is higher outside the wall than inside, they assume any leachate is contained inside the landfill. But resident Sandra Hurley Jewkes says that is no substitute for actually taking water samples near the facility.

JEWKES: I think they aren’t taking them because they don’t want to know.

BASCOMB: Other residents like Elle Baker are frustrated that Wheelabrator spends lavishly to buy good will in the community, but won’t pay for ground water samples or an environmental impact report.

BAKER: If they are willing to write checks for little league, for tree lighting, for other things like this in the community why not for an environmental impact report because that is truly being a good neighbor. That’s truly proving to us the community that maybe … maybe it’s not as dangerous. But they don’t want that to happen. They don’t want to provide that to the community and that’s what’s concerning.

BASCOMB: The only official willing to speak to me about this issue was State Representative Rose Lee Vincint.

VINCENT: I’m determined to make sure that we do whatever we can to, you know, stop this injustice.

The Rumney Marsh is an area prone to flooding. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Representative Vincent has introduced legislation to close the Wheelabrator landfill twice.

VINCENT: It’s just so wrong, how anyone can look at it and think it’s not wrong? Instead of realizing it was wrong but now we can try to do something to fix it, let’s try to mitigate and make it safe. What they want to do though is make it bigger, they don’t want to make it safe.

BASCOMB: Vincent says she is worried about the potential health effects on the community where four generations of her family have lived, where she raised her own children.

VINCENT: My children don’t live here but someone’s children live here now. But it’s not just about my children it’s about everyone’s children. Some day some kids should be able to go fishing in that water.

BASCOMB: Because water samples aren’t taken, there’s no way to know what chemical pollutants or how much might be leaking into the estuary from the landfill. But scientists like George Thurston know what they would expect. Thurston is Director of the Program in Exposure Assessment and Human Health Effects at the NYU School of medicine and has served on the National Academy of Science’s Committee on the Health Effects of Waste Incineration.

Former State Representative Rose Lee Vincent points to the Wheelabrator waste incinerator and landfill. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

THURSTON: Our committee, when we looked at this for the National Academy of Sciences, we identified cadmium, arsenic, mercury and lead as some of the components of particles that were of most health concern.

BASCOMB: He says exposure to those types of pollutants can have serious health effects over time.

THURSTON: Cumulative long-term exposures can increase risk of cancer.

BASCOMB: According to the Massachusetts Cancer Registry, the communities near the facility do have elevated rates of certain cancers including leukemia, testicular cancer, and cancer of the larynx. George Thurston says that’s all the more reason to be careful when permitting more potential exposures. And opening up a capped landfill is inherently more dangerous than leaving the facility closed.

THURSTON: But I would say any time you open up one of these capped facilities then that would increase risk of some sort of accident and getting a release. The biggest concerns are when things don’t go as they should and you need continuous monitoring to determine that.

BASCOMB: Since we first aired this story in 2018 Wheelabrator changed its name to Waste Innovation Technologies.

The Massachusetts DEP did allow for more fly ash dumping at the facility.

The Conservation Law Foundation and the Board of Health for the Town of Saugus argued against that decision but ultimately lost in court.

So, in 2019 the company began filing in the storm water valleys with additional fly ash.

Statement from Wheelabrator Technologies / WIN Waste Innovations

"The waste-to-energy industry is one of the most stringently regulated in the world, and WIN Saugus meets or exceeds all regulations established by the EPA and Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

"A steward of the local environment, WIN Saugus is financially supporting the Dewey Daggett Landfill Remediation that is about to be undertaken by DEP. In the same spirit, WIN supports the Rumney Marshes, a state-designated Area of Critical Environmental Concern, and manages the Bear Creek Wildlife Sanctuary, which is home to 17,000 trees, 200 bird species, 10 beehives and 9 ecosystems.

"In the spirit of collaboration, the Town has created a committee – comprised of town officials, environmental advocates and nearby residents -- to explore how WIN’s presence can best benefit Saugus while protecting the health and safety of its residents. We have been supportive of the committee process and look forward to its recommendations and suggestions as we advance our mission of performance for the planet."

Related links:

- Conservation Law Foundation -about Wheelabrator Incinerator

- Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection -about Wheelabrator Incinerator

- Wheelabrator Saugus Incinerator-company site

[MUSIC: Benny Sings, “Sunny Afternoon” Stones Throw Record]

Rising Seas Threaten Landfills

Sandwiched in between New York City and the urbanized communities of northern New Jersey, restored portions of the Hackensack Meadowland at DeKorte Park in Lyndhurst provide a welcome sanctuary for a wide array of wildlife. Part of the park sits atop an old landfill and a "garbage island" where trash was once dumped illegally. The Meadowlands provide a stop-over for migratory birds travelling the Atlantic Flyway. (Photo: Steven Reynolds, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, the Saugus waste incinerator landfill may be an extreme example but Massachusetts is not alone when it comes to problematic coastal landfills. There are roughly 100,000 landfills across the United States and more than half are on the coast where sea level rise is a serious threat. In fact, scientists tell us to expect several feet of sea level rise in the next century as a result of climate change. Independent journalist Dave Lindorff has been digging into this story for the Nation and he joins me now. Dave Lindorff welcome to Living on Earth.

LINDORFF: Thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: Well, why are there so many landfills sited in coastal areas? I mean, I guess that's where the people live mostly. So it's kind of makes sense, is that all there is to it?

LINDORFF: That's it. You know, historically, landfills have been everywhere people are, and the majority of people live along coastlines. In the US, it's about, I think, 40% of the population lives within something like 40 miles of a coastline. You know, dating back to the industrial era, they've had to put garbage in places and what they do is they pick what are considered wasted land for landfills. And wasted land is defined as land that you can't build taxable property on. And that tends to be swamps, wetlands, river estuaries, and floodplains. And that's exactly what coastlines are. I mean, it's kind of amazing. If you go to a place like the New Jersey wetlands, there are 13 mountainous landfills sitting in the wetlands. And some of them are, you know, as much as 300 feet high, filled with garbage, and closed. So they're covered with sod, they look, they look harmless, because you know, they look like grassy hills. But those waters are going to rise, they had a eight foot storm surge on top of the tide when Hurricane Sandy hit in 2012. When it gets worse, and the water's actually higher, and then you get these storm surges too, the sod is going to take, be taken off the liners that are on whatever of those landfills have liners. And many of them don't, under or over; none of them are lined underneath. And so all of this stuff is vulnerable, it could all wash out.

BASCOMB: And so the concern is literally that rising seas will just come and tear away the landfills and you'll have just garbage emptying out into estuaries, marshes and ultimately the ocean.

LINDORFF: That's right. And the thing about that is you know, remember that these these wetlands are where about 70% of the sea life in the open ocean have part of their reproductive cycle. You know, either whether it's laying eggs or mating up river or having their young, all of these creatures that ecology depends on have to have some kind of pollution-free wetlands or river estuaries for their breeding cycle.

BASCOMB: Well, that's the thing. I mean, when a lot of these landfills were built, I mean, as you said, you know, wetlands were just, you can't farm there, you can't build there, you might as well put your garbage there. But now of course, we know that they're tremendously important ecosystems, as well as protecting from storm surge and, and rising seas. That's kind of adding insult to injury, in a way.

LINDORFF: Yeah, they also are actually, I had in the article some research that showed that wetlands also are major absorbers of CO2. So if you kill off the plant life in them that does that job, you've also worsened global warming, and increased the speed of sea rise.

Photograph from the Gallops Island Incinerator Site in Boston Harbor, Massachusetts. (Photo: Massachusetts Department of Energy, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: And what about saltwater intrusion in these landfills? Does saltwater interact with the material in there in a different way than rainwater would?

LINDORFF: Absolutely, when they say that, you know, these poly plastic liners that they put, sometimes in a newer facility, they say the bottom has a poly plastic liner. And then also they put a poly plastic liner on top when they close a part of a operating dump. And then they cover it with maybe, you know, five or six feet of earth. Those plastic liners are much more vulnerable when they're in saltwater.

BASCOMB: And from what I understand, you know, with these landfills, we're not just talking about solid waste here, you know, plastic cups and diapers and things which are bad enough, but there are also a lot of chemicals and even some nuclear waste that could escape. Can you tell us more about that?

LINDORFF: Here's the other thing, is most of these dumps are pre-1980. I mean, the vast majority of them are pre-1980. We don't know what's in those because there were no regulations whatsoever before 1980 on what could go into a dump. So what you have is a situation where, at a time when the US used to have a lot more manufacturing on chemical industries and things like that they were dumping their waste, their transition chemicals and so on into the local landfill. It was the cheapest place to put it. Even the Manhattan -- they found Manhattan Project waste in one of the New Jersey landfills in the wetlands and had to try to dig it all up and they still haven't succeeded. So that dump, which is closed, called the Edgeboro Landfill, it's got nuclear waste in the bottom of it. This, all of these possibilities, heavy metals, you know, dioxins, everything that's used in manufacturing can be in these dumps, and they aren't lined.

BASCOMB: Because it seems like nobody's really talking about this right now or, or making a plan to address it and you write in your article that the EPA, which would seem like the obvious government agency to, you know, spearhead taking care of this problem. They don't actually have jurisdiction over these landfills. Could you tell us about that?

LINDORFF: Congress would have to give them jurisdiction, they actually recently waived any regulation at all of landfills that are receiving less than 20 tons of garbage per day. That's a lot of garbage! [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: Indeed. So that leaves it to states and local municipalities to try to do something with these facilities?

LINDORFF: Right, exactly.

BASCOMB: Well, we are in this situation, and I think people are probably becoming more aware of the potential consequences of sea level rise, and hopefully including this issue of landfills. Where do we go from here? Are there any state or local governments or even international municipalities or governments that are looking at this issue that maybe can, you know, serve as a roadmap for, for the rest of us as we're going forward?

LINDORFF: Unfortunately not. I mean, the closest I can think of is the UK because when I initially started the story's research, I Googled "coastal landfills threatened by sea level rise," and the only thing I got was this study at the University of Southampton. And that was a government funded study, they came up with a list of recommendations. And you know, a survey of all the threatened areas and landfills, and that was a big step forward. I would say the first thing is that the EPA should do cataloging of all these landfills and find out in a governmental way, what the issue is and how big it is and how it could be solved. And then, you know, maybe people will start addressing it.

BASCOMB: Dave Lindorff is an independent journalist contributing to The Nation. Dave, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

LINDORFF: Thank you for having me on.

Related links:

- Read Dave Lindorrf’s article in The Nation about coastal landfills and rising sea levels

- SCOPAC Coastal Landfills Study: Coastal Flooding, Erosion and Funding Assessment

- Read EPA’s study on ‘Vulnerability of Waste Infrastructure to Climate Induced Impacts in Coastal Communities'

[MUSIC: John Scofield, “Just Don’t Want To Be Lonely” on Überjam Deux, Longsolo]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Genevieve Santilli, Teresa Shi, Gabriell Urton, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the

University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth