May 29, 2020

Air Date: May 29, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Hurricanes and COVID-19

View the page for this story

2020 is likely to be the warmest on record and the Atlantic hurricane season is predicted to be worse than average with three or more extremely dangerous storms. Should those storms come ashore FEMA, the US agency responsible for disaster recovery and response, is at risk of being overwhelmed as it already has to handle the novel coronavirus pandemic, and a backlog from past storms, wildfires and floods. For more on the intersection between storm response and COVID-19, Host Steve Curwood talks with Rachel Cleetus, Lead Economist and Policy Director for the Climate and Energy Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. (09:30)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News weekend editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss how stagnant plumbing may pose a health risk as public buildings that had been shut down during the pandemic reopen. Also, it’s now easier for people in urban areas to hear bird songs, as noise pollution has decreased due to the pandemic. And in environmental history, they discuss the 50th anniversary of the peregrine falcon, the brown pelican, and the leatherback sea turtle joining the endangered species list. (04:46)

Outdoor Learning Safer in the Pandemic

View the page for this story

As schools and pre-schools prepare to reopen, some educators are considering the benefits of outdoor learning to help lower the risk of Covid-19 transmission. In Scotland, nature-based preschools were already popular before the pandemic. Cameron Sprague, a team leader at nature-based Stramash nursery school in Fort William, Scotland, spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb about how he and his fellow educators incorporate outdoor learning into their preschool curriculum, and the many benefits of outdoor education. (09:38)

The Pear Tree

/ Jennifer BerryView the page for this story

Writer Jennifer Berry reflects on the wonders of a pear tree from her pre-pandemic life. Warblers, mockingbirds, and cedar waxwings are just a few of the creatures that find a feast in an old yet fruitful pear tree. (02:45)

Climate and Marine Disease

/ Kori SuzukiView the page for this story

Climate disruption is wreaking havoc on the oceans of the world and the creatures that live there, including sea stars and salmon. Kori Suzuki reports. (04:17)

Why Fish Don’t Exist

View the page for this story

Fish scientist David Starr Jordan discovered thousands of new fish species around 1900, and kept going even as he faced repeated disasters that threatened to obliterate his life’s work. His stubborn optimism is the springboard for science journalist Lulu Miller’s new book, “Why Fish Don’t Exist”, and the search for order in a cold, chaotic world. Lulu Miller and Host Steve Curwood discuss what her journey into science and the past uncovered about the astonishing life of David Starr Jordan. (15:44)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Rachel Cleetus, Lulu Miller, Cameron Sprague

REPORTERS: Jennifer Berry, Peter Dykstra, Kori Suzuki

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX– this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

As hurricane season begins preparations for evacuees are complicated by the coronavirus pandemic.

CLEETUS: They’re going to have to make sure that they’re carrying supplies with them including face masks, hand sanitizers, and other kinds of public health precautions. They’re going to need to maintain social distancing.

CURWOOD: Also, outdoor education can help limit the spread of the virus.

SPRAGUE: Being in heated non-ventilated rooms is the petri dish for picking up bugs that's just what happens in schools but by being outside we're avoiding that. For example, we had a parent that unfortunately came down with cancer and they pulled their child out of their indoor setting and put them in here because they were worried about them picking up other bugs from children.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Hurricanes and COVID-19

The Georgia National Guard assists the Atlanta Community Food Bank as part of the US’ Coronavirus response. (Photo: Georgia National Guard, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency or FEMA has been stretched thin by the corona virus pandemic and a backlog from previous disasters including Hurricanes Harvey and Maria. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts 2020 will have more hurricanes than average, with three or more extremely dangerous storms. Some experts say that with the pandemic FEMA is in no shape to handle these storms if they come ashore. And research finds the number of major storms is increasing as the planet warms, with 2020 likely to be the warmest year on record. Already before the June first start of the 2020 hurricane season tropical storms Arthur and Bertha formed, and Bertha battered the Carolinas. For more on the intersection of COVID-19 and hurricanes, we’re joined by Rachel Cleetus, lead Economist and Policy Director for the Climate and Energy Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Rachel, welcome back to Living on Earth!

CLEETUS: Hi, Steve, thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So, the Atlantic hurricane season officially begins June 1st. But scientists are saying that the 2020 season is already on track to be worse than the average season. Why is that?

CLEETUS: So, what that means is that there's going to be a likely range of six-to-ten hurricanes, with three-to-six of them being major hurricanes; that means Category Three or above, expected this year. And these kinds of hurricanes are the ones that, if they make landfall, cause really catastrophic impacts. They have high winds, they're carrying a lot of precipitation. The other challenges that we've seen in recent years, these hurricanes also intensify faster compared to historical records. That means that we're seeing very, very powerful storms form quickly, meaning that people have less window to evacuate when these really major storms are turning up. And this year, we see many of the ingredients for a very active hurricane season: sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic and the Caribbean Sea are high, we don't have an El Nino this year to interfere with the formation of these storms. So, we're likely to see an above-average hurricane season, and the sobering reality is this year the hurricane season is going to collide with the COVID-19 pandemic, compounding the risks to people all along the Gulf and East Coast of the US.

CURWOOD: Of course, there's the immediate threat to human life and property. And then there's a question of, of the economy and, and how these areas, how folks recover. Describe for me some of the compound risks from these kinds of events.

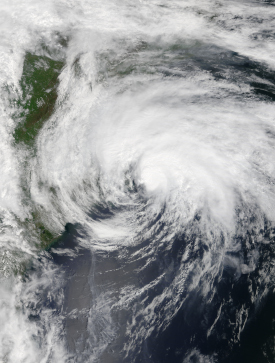

Tropical Storm Arthur on May 18th, 2020. 2020 is the sixth consecutive year where a tropical storm has formed before the official start to the hurricane season, which is June 1st. (Photo: NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CLEETUS: What we're seeing this year is that these climate hazards, which are increasing in frequency and intensity under climate change are likely to intersect with COVID-19 outbreaks, both here in the US and around the world. And these compound risks will exacerbate and be exacerbated by the unfolding economic crisis as well. As well as long standing social and racial disparities. So here in the US, for example, we're seeing African American people die at three times the rate as white people under this COVID-19 epidemic. The unemployment in the US has surged past 38 million, and the unemployment rate is much higher for communities of color. And this makes it even more complicated when a disaster strikes, because people are already going into this hurricane season under siege from both economic and COVID-19 crises. And a disaster like a hurricane will only exacerbate the impact on people.

CURWOOD: Well, we're seeing that it's challenging to maintain what we call social distancing and wearing masks. And yet if we don't follow that kind of advice when something like a hurricane or a pandemic or both come at the same time, what kind of trouble do you think we're in?

CLEETUS: Look, even under regular circumstances evacuating, and sheltering in anticipation of a hurricane is very challenging. It's really hard for people to make that decision to leave their home, to go somewhere else. And yet, this year, it's going to be even more important that people heed these warnings well in advance, they're going to need to find out where they can go and how to go there safely during this COVID-19 pandemic. They're going to have to make sure that they're carrying supplies with them, including face masks, hand sanitizers and other kinds of public health precautions. They're going to need to maintain social distancing. It's going to be very challenging for state and local authorities as well, because they have to figure out how to shelter people, how to get people out of harm's way, while maintaining social distancing. Especially those populations who might be vulnerable like people in nursing homes, the elderly, others may not be able to afford actuate by themselves or may not have transportation, may not have the resources to evacuate. We're going to need an extraordinary effort from state, local, and federal authorities to keep people safe this hurricane season, even in the midst of a COVID-19 pandemic.

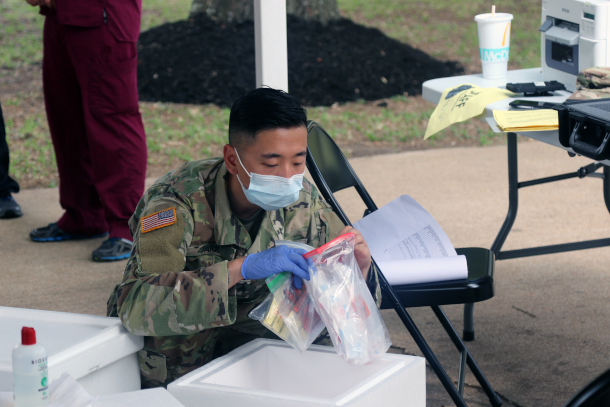

A solider with the Texas National Guard processes sample bags with COVID-19 tests as part of FEMA’s Coronavirus response. (Photo: Texas National Guard, Flickr, CC BY 2,0)

CURWOOD: The Federal Emergency Management Agency, FEMA, is the part of the federal government that is tasked with leading hurricane response and recovery efforts. But last I looked, they're also handling some other disasters, chiefly the novel Coronavirus response. Some suggests that FEMA is going to be stretched too thin. How accurate would you say that statement is?

CLEETUS: There's no question that FEMA has already stretched thin as we go into this hurricane season. So FEMA is coordinating our nation's response to the COVID-19 crisis. It's the nation's lead disaster response agency as well. So, it will be responsible for other kinds of disasters like hurricanes, wildfires. We've already seen it have to deploy for flooding this year in the Midwest. And so, we have an agency that is now responding to 57 disaster declarations. We have a nationwide disaster declaration in every single state, five territories, in tribal communities as well. And FEMA is coordinating all those responses. So, now when you imagine a hurricane season on top of that, you can see an agency that's going to be very, very stretched. We have still not recovered from past disasters, previous hurricane seasons, like the extraordinary 2017 and 2018 hurricane seasons. And that means that FEMA is still trying to help communities recover from those past disasters, even ahead of this year. FEMA is certainly recognizing that the COVID-19 pandemic is going to have a significant impact on its operations. And they want to shift as far as possible to remote operations, especially in places where there is a COVID-19 outbreak. And I just want to remind your listeners, the hurricane season stretches all the way through November 30. And public health experts are telling us that we will very likely see another wave of COVID-19 outbreaks around the country later this summer, early in fall. So how does an agency coordinate its disaster response which really requires engaging with people, making sure people are evacuated safely, making sure that they're sheltering safely. These are not things that can be done remotely. There are some pieces of this that can be done, but the reality is, we do need federal, state, and local authorities to help people get out of the way and stay safe.

CURWOOD: Sounds to me that there're gonna be many people, if and when a major hurricane strikes, they're gonna be more or less on their own.

CLEETUS: There will hopefully be very clear guidance and communications from federal, state, and local authorities telling people when a major hurricane or other type of disaster is likely to come so that they can get out of the way, in time, safely. But, yes, unfortunately, a lot of the responsibility does fall to individuals to make those decisions and to make them in time. So what's really important right now is if you are in one of these places that is hurricane prone, please make sure that you have prepared well in advance that you have the supplies that you would need, that you know where you would likely go, if such an event were to happen, and that you know where to get the best and most updated information to help you stay prepared.

Rachel Cleetus is the Lead Economist and Policy Director for Climate and Energy at the Union of Concerned Scientists. (Photo: Courtesy of Rachel Cleetus)

CURWOOD: So, what role does Congress play in all this, when it comes to America?

CLEETUS: Well, this year we've seen as part of the CARES Act, there was an increased allocation, $45 billion for FEMA Disaster Relief Fund, $25 billion of which is to be allocated for major disasters. Going into this hurricane season, FEMA does have this funding, but it can quickly dissipate if we do have major landfalling hurricanes, so Congress does need to stand at the ready to help the agency should there be a number of disasters. Because of course, this money is not just about hurricanes. It's also helping with the COVID-19 pandemic, with wildfires, with flooding, inland flooding, with droughts. This is for disasters across the board.

CURWOOD: Rachel Cleetus is the Climate and Energy Policy Director at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Rachel.

CLEETUS: Steve, thank you for having me.

Related links:

- NOAA 2020 Hurricane Season Predictions

- Read Rachel Cleetus’ article on the 2020 hurricane season

- Blog entry from the Union of Concerned Scientists: “Dangerous Hurricane Season to Open Amidst COVID-19”

- More on Rachel Cleetus at the Union of Concerned Scientists

[MUSIC: Peter Ostroushko and Ensemble, “Uncommon Ground” on Minnesota – A History Of the Land, by Peter Ostroushko, Red House Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Reopening public buildings may pose health risks other than the spread of the virus, such as idle plumbing if internal water systems go unchecked. (Photo: Harshil Shah, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, it's time now to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News - that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia, hey Peter, what stories we going to talk about today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. Our friends at the nonprofit Circle of Blue do a great job reporting on water stories, about scarcity, about pollution, and here's one they recently published that I hadn't considered. Schools and workplaces and all the public buildings that have been shut down for a month or two months or three months due to Coronavirus may pose a risk when they open back up due to idle plumbing.

CURWOOD: Idle plumbing?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, the pipes that in some cases can become petri dishes for growing viruses or bacteria when they're not being used.

CURWOOD: Oh, right. Yeah, that's what happened with Legionnaires' disease. Apparently there was some stubs of plumbing that hadn't been used for a while, and that's where the bacteria grew.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, plumbing, and also the air conditioning system acquired moisture. Legionnaires' disease got its name back in 1976. The American Legion Convention held in Philadelphia that year for the Bicentennial, about 200 legionnaires and hotel staff got lung infections from hotel air conditioning that had been idled for some time before. And ultimately 29 of them died. Another risk in all of this is accumulation of metals in plumbing and water carriers, particularly lead and older lead pipes. And of course, everyone knows the disasters with lead that have been uncovered in Flint, Michigan and other cities.

CURWOOD: That's right. All right, Peter. Well, tell me some good news that's going on during the pandemic. I could use a bit of that.

DYKSTRA: Here's a tiny bit of good news. It's another one of those things that's completely unexpected. It's easier for people, particularly in urban environments, to hear bird songs.

CURWOOD: Huh. What, because there's less street noise or something?

People in urban environments are starting to hear more birdsong, thanks to less human activity on the streets. (Photo: Sergei Gussev, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, social distancing, less traffic, less noise, less pollution on the street. People are tuning into the songs of birds. Here in Atlanta I live on the sixth floor of a big building. I can hear the birds from the street. It's not just in places like Atlanta or Boston or Washington, but also the United Arab Emirates. Other places that have some of the same restrictions on travel with social distancing, that have cleaner air, less human traffic, less human noise, and the birds because of it all get a little bit bolder, and going where they want to go.

CURWOOD: Some might say that nature is singing that we're taking it slow, huh?

DYKSTRA: That's right, you can sing that again.

CURWOOD: Let's move on to history now, and tell me what you see.

DYKSTRA: We have a 50th anniversary. If we go back to June 2, 1970, three very prominent megafauna species join the endangered list. This is actually before the U.S. Endangered Species Act that we all know. A precursor law was called the Endangered Species Conservation Act, and joining that list were the peregrine falcon, the brown pelican, and my absolute favorite, the leatherback sea turtle.

CURWOOD: And so how have those creatures fared?

DYKSTRA: Falcons and pelicans have recovered, but the leatherback has not recovered.

CURWOOD: Oh no, those are my favorite turtles too. I mean, they're just amazing.

Leatherback sea turtles continue to face threats due to human activity, such as disruption of nesting sites and an abundance of plastic pollution. (Photo: Alastair Rae, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: They are. They can weigh close to a ton, they have soft shells as opposed to the hard shells of other sea turtles. Those shells have what looks kind of like racing stripes on them. And with their enormous size, they always kind of reminded me of Volkswagen Beetles with flippers on them.

CURWOOD: Yeah. So what helped the birds, the falcons and the pelicans?

DYKSTRA: What helped a lot of birds was the outlawing of DDT. That happened two years after these two birds made the endangered list. DDT of course thinned the egg shells of bird species, caused a lot of mortality from bald eagles down to hummingbirds. It's since been outlawed in most countries. It's allowed many bird species, including peregrine falcons and brown pelicans, to bounce back.

CURWOOD: And what's the continuing set of troubles for the leatherback turtles?

DYKSTRA: Several things: bycatch from fishing fleets, destruction of nesting sites on beaches, and of course leatherbacks ingest a whole lot of plastic, frequently plastic bags that the turtles mistake for their favorite food, jellyfish.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News - that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon, Peter.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: My pleasure. And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Circle of Blue | “Water Contamination Risks Lurk in Plumbing of Idled Buildings”

- Lehigh Valley Health Network | Legionella and Dormant Water Systems: A COVID-19 Shutdown Health Risk

- The Washington Post | “Amid the Pandemic, People Are Paying More Attention to Tweets. And Not the Twitter Kind.”

- More on the Leatherback Sea Turtle from National Geographic

[MUSIC: Syltans of String, “Pinball Wizard” on Yalla Yalla, by Pete Townshend, arr.Sultans of String, Sultans of String with Ontario Arts Council]

CURWOOD: Coming up- how the pandemic helped one woman savor a bit of nature she used to ignore. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Sultans of String, “Stomping At the Rex” on Yalla Yalla, by McKhool & Laliberte, Sultans of String with Ontario Arts Council]

Outdoor Learning Safer in the Pandemic

Stramash Nursery School is located in Scotland’s Highlands. (Photo: Courtesy of Cameron Sprague)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

More than a century ago philosopher and psychologist John Dewey argued that children should be free to walk in and out of classrooms and go outside to learn on their own terms with practical hands-on experience. And today we know that sterilizing sunlight and moving air sharply reduce the transmissibility of the coronavirus and other respiratory diseases. So, some educators are looking again at the developmental advantages of outdoor education with the added value of reducing the risk of spreading infections. Preschoolers are notorious for bringing germs home, but it’s impractical to keep a mask on them or enforce distancing. So, some educators in Scotland are among those looking to add more outdoor education venues as a way to help keep kids and families healthy in light of the coronavirus pandemic. Nature-based pre-schools are already popular in this cold and rainy region. Cameron Sprague is a team leader at Stramash Nursery School in Fort William, Scotland and spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: So Cameron, tell me about your school. What does it look like there?

Children don their winter gear to prepare to learn outside on a cold, rainy day in Scotland. (Photo: Courtesy of Cameron Sprague)

SPRAGUE: I think one thing to do with outdoor education is that it doesn't mean you have to be in the woods and I think a lot of times people connect to that feeling. So we have a massive field that we affectionately called the Field of Dreams that is full of loose parts and play structures but within that is a shelter that is kind of a mix of a Mongolian Yurt, but we call it a yurkie with a porch on it. So the inside of the yurkie has a massive 15 kilowatt wood stove it has soft furnishings, big family dining room table, so it is like a family home. That's the feel we want to go for it's very Scandinavian. And attached to that is a big porch so the kids can come in, they can take their wet gear off and they can go through and warm up. And in addition to that, we have two basically adventure tent teepees that we can put up and take down so that the kids can be more mobile and sprint in and out of their wet stuff. But just to get out of wind and wet and be a bit warmer, they can do that. And throughout the site, there are sheltered areas with hammocks and things like that. So you can take a rest and get out of it, but still experience being outdoors as much as possible. And we're very much child-led practice. So children are their own decision makers and we just help facilitate their learning rather than directing and guiding and pushing.

BASCOMB: And how has Scotland's outdoor learning facilities in your school in particular how have they changed since the pandemic began if at all?

Children gather for storytime outdoors. (Photo: Wellspring Community School, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

SPRAGUE: Yeah, so we and several other outdoor nurseries within Scotland are operating as what they’re calling hubs for frontline workers. So since the lockdown happened since March here, we've been open for nurses, children, police, utility workers, so that they can still you know, keep the country going and moving but they needed somewhere for the children to be. So it's been a change for us because it's one of the things we have to do is take younger children. So we've had children under two years old, we offered ourselves up because it made sense for us like an infection is not just going to spread outside as much. But what do we need to do? So things we've done is have PPE that we wear only on site and if it's leaving site, it gets bagged up and immediately washed. So that is something different for us, we might have just rocked up in a t-shirt and shorts on a nice day but now we have a total change of clothes for that. And we've always done really strict hand washing around meal times and after toileting. We've now increased that periodically throughout the day the children wash their hands additional times, and just making sure we're educating ourselves as much as possible and in talking to the children about it as well, but you can't get a two year old to socially distance, it's impossible and, and even just caring for them. You know, we had lots of talks about you know, should we wear face masks or not. And as a team we decided not to because you know, these kids were going through a huge transition, the whole world's changed around us. Whatever their routine was it is different, and we're trying to transition them and settle them into meeting totally new people. And we didn't think you could do that behind the mask very easily. Kids, especially nonverbal children respond to smiles and things like that so we made that decision. And that was really something that I'm glad we did, because I don't think it would have worked otherwise.

BASCOMB: Scotland's Children's Minister, Maree Todd has been a strong advocate of outdoor education from what I understand. She's even said that educating children outside could minimize the transmission of the virus. What do you think of that notion?

SPRAGUE: I 100% agree. I think Scotland has been moving practice outdoors. And that even before the pandemic, the expectation, especially in early years was that your children would be outdoors no matter what, and that's what the guidance has been coming out. But in terms of infection control, there's been research recently that's come out of Japan that said you're 19 times less likely to catch Coronavirus outdoors. China had similar research where they were looking at different spreading events and found only one that happened outdoors. And, you know, that's something naturally within our practice that, for example, we had a parent that my very first year with us nursery that, unfortunately came down with cancer and they pulled their child out of their kind of indoor setting and put them in here full time because they were worried about them picking up other bugs from children. So we kind of always knew that, you know, being in heated, non ventilated rooms is, you know, kind of a petri dish for picking up bugs and that's kind of just what happens in schools. But while being outside we're avoiding that.

Outdoor education can encourage children to be more creative and ask more questions. (Photo: woodleywonderworks, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. Yeah, that makes sense. Are there any other diseases that you're aware of that are maybe minimize you know, the transmission is minimized in an outdoor setting versus a classroom?

SPRAGUE: Well, I think even just common colds, chickenpox. Well like norovirus you know, there's been plenty of times when the schools in our surrounding area have had large numbers of children and staff that have been off sick and we just don't have it. It just doesn't happen.

BASCOMB: Now, what do you see as the advantages of nature based education as opposed to a more traditional school held inside of a classroom, you know, other than the health benefits that we've been talking about?

SPRAGUE: I think there's so much that just with lifestyles changing, that children are missing out, children are more sedentary than ever. And I know that goes with health and well being but your body is also linked to learning. They did research here when they were writing one of the Early Years Documents, and found kids are physically two years behind where they should be starting primary school, which is the equivalent of elementary here. And when you think that that's potentially half your life, you're physically behind where you should be. That's a scary thing. And that's stuff like your muscle tone not being developed so that you can actually hold a pencil and learn to write. Your emotional regulation and audio visual systems are linked to your core muscles and if those are underdeveloped, then you might get diagnosed with ADHD when really you're just haven't had a chance to build your body and mature and settle into your yourself. It's emotional well being as well NHS in Highland where I am, has been prescribing at least for a year outdoor time for mental well being and just help him get outside. One of the other big things for us for kids is kids are losing creativity. So being outside playing with loose parts, all those kinds of things that we do we're giving children that foundation to be creative and going to school and be inquisitive, actually questioning and asking and you know, a lot of times people say oh, I want them to be school ready. And really they mean compliant, like sit down and do what I'm told. And really, we want our kids ready to learn and have life skills and that's what being outside allows them to do.

Children who learn through outdoor education show fewer instances of obesity, diabetes and ADHD. (Photo: USFWS - Pacific Region, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: And what about outdoor education and, you know, self esteem and social skills, that sort of thing. Do you find there's a significant difference there?

SPRAGUE: Yeah, absolutely. And I think kids climbing trees using fire, all that kind of stuff there is an element of risk in it but what also comes from it is confidence and self esteem. You know, I did that I made that happen. I climbed that tree, all those kind of things. And one of the things that as adults and I guess maybe Western society does is underestimate the capabilities of children big time. And for one of our rules is, we don't put children into anything even a swing because we want them to develop the skills and problem solve and be physically ready to be in things and then we know we're safe. If we let them build those skills themselves, then they're safe to be up there. And then they get that confidence boost that self esteem boost because I did it and that's exciting and then we're there to celebrate it with them.

Cameron Sprague is a team leader at Stramash Nursery School in Fort William, Scotland. (Photo: Courtesy of Cameron Sprague)

BASCOMB: Yeah, it sounds like there's a lot of benefits across the board. I live in New Hampshire and a lot of the northern half of the United States anyway, it's really cold in the wintertime. You know, I think it might be a tough sell for students and teachers for that matter to get outside in December, January to teach math. You know, what would you say to that?

SPRAGUE: I would say you just need to think of different materials I guess. It's the old Scandinavian saying there's no bad weather just bad clothing. So it's dressing appropriately taking precautions we use things like tipis which you can put fires in, so kids can dip in and out and warm up. So there's always options and ways to keep children safe. Yeah, lightning, hurricanes. Yeah, you're, outside teaching math, but on a normal cold, windy wet day then yes you can be.

CURWOOD: Cameron Sprague is a team leader at Stramash Nursery School in Fort William, Scotland and spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “Scotland Eyes Outdoor Education as Model for Opening Schools”

- Read more about Scotland’s Curriculum of Excellence

- Click here to learn more about Stramash Nursery School

[MUSIC: Phil Cunningham, “Ceilidh Funk” on The Palomino Waltz, anonymous/arr.Phil Cunningham/Foss Paterson, Green Linnet]

The Pear Tree

A mockingbird eyes tiny fruit in a pear tree. (Photo: ptgbirdlover, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: As the Covid-19 pandemic has emptied many office buildings once ordinary things can become fonder memories as writer Jennifer Berry of Sacramento, California reminds us.

BERRY: In the time before the virus, the view from my office looked upon an old, neglected pear tree I’d found disappointing. Snapped branches dangled like broken bones, blooms of mistletoe swelled in its canopy and water sprouts sprung upward like quills from every branch. I resigned myself to this meager connection to the natural world outside.

“Blooms of mistletoe swelled in its canopy.” (Photo: St. John’s College Cambridge, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[MUSIC]

BERRY: Then one day a mockingbird came to visit. And every day after that. Over the months, I came to know this bird well — the cock of its head to eye something interesting, the precision with which it floats between branches, and its easy regard for other birds who stop by for a visit, unlike the scrub jays who chase everyone away.

[MUSIC]

A squirrel munches a tiny pear. (Photo: Perry Quan, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

BERRY: Then winter came. And the tree, now bejeweled with tiny, bitter pears no bigger than olives, became this hallowed giver of life. The mockingbird plucked the fruit and swooped to the ground to peck it apart. The warblers preferred to peck the pears while they hung like piñatas. The crows moved in, took residence and one dive-bombed a squirrel that munched its way around the fruit as little flecks flew in every direction. But the squirrel simply ignored the assaults and turned its rear end toward the crow. Then the Cedar Waxwings came with their face masks and crests, and picked the tree clean.

[MUSIC]

BERRY: Then spring began to unfurl new life. Woodpeckers fish insects from the bark’s fissures, the crows yank at twigs for their nests and the bees hum over the welcoming blossoms. I wonder what comes next?

[MUSIC]

BERRY: But I work at home now, like so many others, rooted to our homes. I miss the pear tree and the rich life it supports.

“The Cedar Waxwings came with their facemasks and crests, and picked the tree clean.” (Photo: Mike’s Birds, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

[MUSIC]

BERRY: Today, a goldfinch perched in the cover of my passion fruit vine outside my window at home and it took me back to that same feeling inspired by the pear tree, that we are never alone.

[MUSIC]

BERRY: And for now, maybe that’s all I really need.

CURWOOD: That’s writer Jennifer Berry with --“The Pear Tree”

Related link:

About writer Jennifer Berry

[MUSIC: Susan Robbins/Michael Cicone, “Househunting” on Sea Change, by M.Cicone, Mudscraper Music]

Climate and Marine Disease

The leg of this purple ochre sea star in Oregon is disintegrating, as it dies from sea star wasting syndrome. (Photo: Elizabeth Cerny-Chipman, Oregon State University, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Climate change is wreaking havoc on the oceans of the world and the creatures that live there, including sea stars, which are the victims of a grisly disease known as sea star wasting syndrome. Kori Suzuki has the story.

SUZUKI: In 2013, Drew Harvell was walking down Alki Beach in Seattle.

HARVELL: We found stars that were losing their arms; we found arms that didn't have stars; we found stars where their arms were literally in the process of kind of ripping off and their internal organs spilling out.

SUZUKI: Harvell is a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Cornell University.

HARVELL: And this was in the dark by headlamp, so the whole thing was kind of a ghoulish, ghastly scene, really.

SUZUKI: I’m speaking with her at the 2020 American Association for the Advancement of Science Meeting where she’s presenting new research on marine diseases like sea star wasting syndrome—a mysterious, fast-acting disease that causes tissue decay, and can eventually cause infected sea stars to break apart and die.

The sea stars Harvell studies are critical to marine ecosystems. They live in kelp forests, which are home to thousands of fish and other species. Kelp forests are also food for sea urchins. A healthy sea star population feeds on sea urchins, keeping that population in check. But without them, sea urchins can take over.

HARVELL: We're finding huge outbreaks of sea urchins, they create areas that we call urchin barrens that are devoid of kelp.

SUZUKI: The biological cause of sea star wasting syndrome is still unknown. But Harvell’s research has uncovered a major factor driving the disease: climate change.

The world where this young salmon will grow up will be far different than that of its parents, and that change will be encoded by the stress response genes in its DNA. (Photo: Flickr, Roger Tabor (USFWS), CC BY-NC 2.0)

As temperatures rise on land, the ocean is also getting warmer. In September, a major United Nations report described underwater heat waves sweeping across the planet. Now, researchers say those heat spikes are fueling disease outbreaks in marine species like sea stars, seagrass and salmon.

MILLER: What we find is that the vast majority of infective agents that infect salmon are positively influenced by temperature.

SUZUKI: That’s Kristi Miller, a professor at Fisheries and Oceans Canada. She says that unusually warm waters cause stress in salmon, making them less prepared to fight off a disease. At the same time, many diseases spread faster at higher temperatures. Miller says these different stressors can work together to fuel the spread of a disease.

MILLER: The presence of two or more stressors can actually create a much stronger effect negative impact on the host or the organism.

SUZUKI: That means disease outbreaks in warming waters can be much worse. In some cases, Miller found that a temperature increase of less than 5 degrees Fahrenheit meant a 60 percent increase in the presence of a pathogen.

But her program has developed a new tool to map these diseases and stressors. It turns out that, when a salmon experiences something like higher-than-normal temperatures, that stress activates a unique genetic response.

Kelp forests like this one off the coast of La Jolla California are threatened by marine diseases which disrupt the underwater food web. When sea stars die in large numbers, the urchins they usually keep in check can chomp their way through kelp forests. (Photo: Camille Pagniello (California Sea Grant), Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MILLER: So a thermal stress will cause a general stress response, but it will also cause the activation of a specific series of genes that will be turned on to make proteins to respond to that thermal assault.

SUZUKI: When that same salmon experiences a different stressor like saltier water, that activates a different genetic response. And Miller and her program can read those signs.

MILLER: What that allows you to do, it allows you to go out into the field and map stressors -- map stressors not just by measuring things in the field but by actually measuring these gene responses in salmon.

SUZUKI: Miller’s program used this technique to look at how disease outbreaks in salmon overlap with other environmental factors—and to show that rising temperatures are fueling those outbreaks. And she says this is a big breakthrough for researchers trying to protect salmon and other keystone species.

MILLER: The reason that that's important is we can't control and mitigate everything. An so if you know what those relationships are and you can say I can't do anything about you know the the prevalence of this infectious agent but I can do something about the level of oxygen in this area or or whatever whatever then you can mitigate that and try to bring down the level of stress and disease.

SUZUKI: For a species like salmon, Miller says mitigating the factors we have control over could make the difference between extinction and a sustainable population.

For Living on Earth, I’m Kori Suzuki.

CURWOOD: Freelance reporter Kori Suzuki’s story comes to us with support from the National Science Writers Association.

Related links:

- Click here to find out more about Sea star wasting disease

- Read about the Strategic Salmon Health Initiative, a group hoping to use genetic tools to identify stress markers in Salmon

[MUSIC: Virginia Rosa, “La Vai Alguem” on Dreamland, by Paolo Tatit – Ze Miguel Wisnick, Putumayo]

CURWOOD: Coming up Lulu Miller on, Why Fish Don’t Exist. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Buckshot Lefonque, “Junge Grove” on Music Evolution, by B. Marsalis, Columbia Records]

Why Fish Don’t Exist

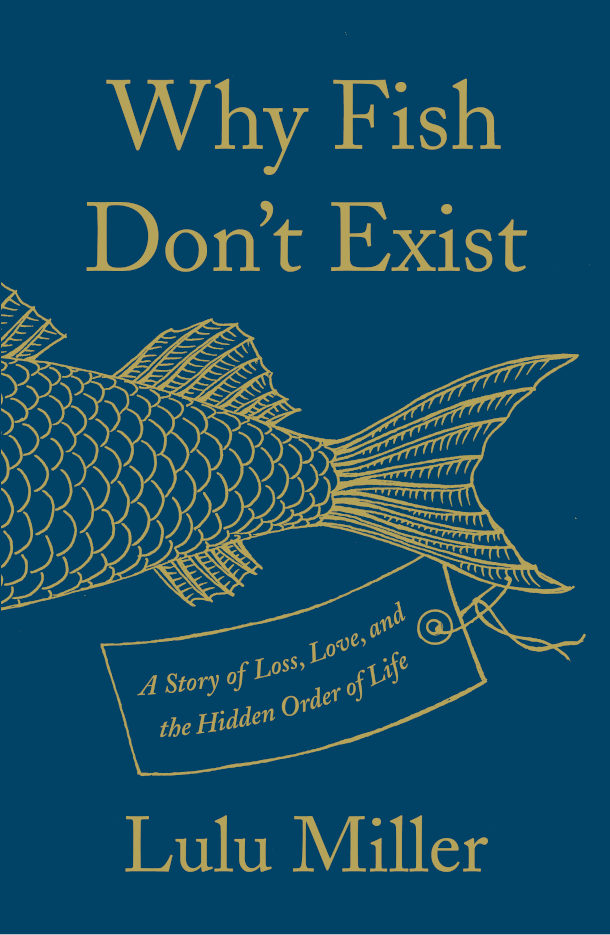

“Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life” is Lulu Miller’s first book. (Image: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

"Chaos is the only sure thing in this world, the master that rules us all," writes science journalist Lulu Miller in her book, “Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life". Lulu is the cofounder of NPR’s “Invisibilia” and her book marvels at the obsessive efforts of a scientist named David Starr Jordan, to defy chaos more than a century ago as he discovered and named thousands of new fish species. In his efforts to bring order to the classification of organisms based on evolution he also relentlessly sought to bring order to his own life, though disaster after disaster threatened to obliterate his life’s work. Lulu Miller joins me now from Chicago. Welcome!

MILLER: Thank you so much for having me. I've been a huge fan of the show for years, and it's a real treat to be with you.

CURWOOD: Lulu, let's start where you started on this book project. What about David Starr Jordan, this obscure ichthyologist, fish scientist, caught your eye and why?

MILLER: Yeah, why! You know, I didn't even know his name at first. I had just heard this one detail about somebody, the person in charge of a fish collection in San Francisco, that was destroyed after the 1906 earthquake. Hundreds of fish fell, the jars were shattered, they were separated from their names. And I had just heard this detail that after the earthquake, instead of just kind of giving up and being overwhelmed, this man innovated and he started this new way of attaching labels to the fish. He sewed them on with a sewing needle as this kind of hope that chaos would never get him again. And it was this really tiny detail that for some reason just kind of made me chuckle and made me think, Oh, he's such a good emblem for the human spirit, like our refusal to back down even when, when the world completely destroys our mission. And I just slowly began to wonder about him. I began to wonder, hey, did his trick work? Did chaos get him later? What, what becomes of someone so confident in the face of chaos itself?

CURWOOD: Of course, he was a collector of all those fish. Part of your book explores collecting as a passion. What is it about collecting as a passion?

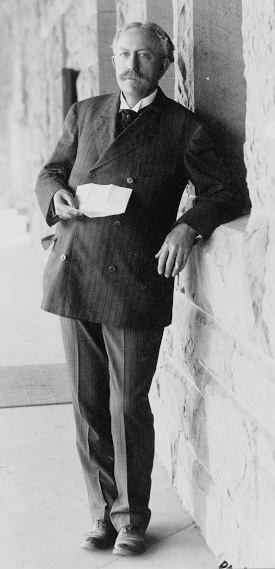

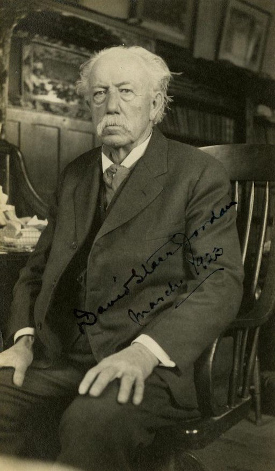

David Starr Jordan in 1908. (Photo: F. Davey, Public Domain)

MILLER: I just think there's something so human about it, and so odd when you zoom out, like, I think that was one of the things that drew me in. What is this desire to preserve and order, to fussily arrange everything? For him, it's natural objects, it's fish. And so he's trying to understand the shape of the great tree of life and how everything is connected evolutionarily to one another. But we all do this in certain ways. You know, as a documentarian, I'm walking around with a microphone all the time collecting moments, and it's like a tick, I can't stop. And I think there's part of me that wonders where that desperation comes from in people. And so I think in certain ways, I, it was a very different form: collecting fish, versus collecting moments and memories, but I think I really identified with him. And I kind of wondered, what becomes of you when you don't even let yourself get a handle on it, like, he just gave into it and he was just so obsessive.

CURWOOD: Your own writing suggests that maybe collecting is a way to deal with chaos.

MILLER: Absolutely. Yes, I think it is one of the few ways; you might not be able to stop the lightning or the earthquake or the virus; you know, you might not be able to stop it. But if you can collect little bits of information, little bits of the world; if you can know them, if you can name them, with more and more accuracy, you might have better ability, I think, to protect yourself from the chaos, or at least have the illusion of control. There's a psychologist, Werner Muensterberger, I write about who studied obsessive collectors for decades. And he wrote that oftentimes people's collecting became sort of pathological and obsessive after some huge deprivation or tragedy, and that with each new acquisition, there was this temporary burst of, he called it, "fantasized omnipotence". Like, this little hit, that you have control, in a world where we know we don't.

CURWOOD: Who was this guy, really, this fish scientist David Starr Jordan?

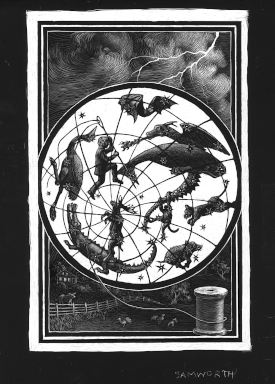

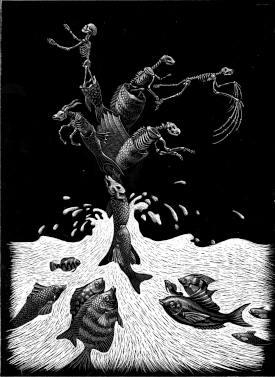

The artwork for the book’s prologue. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

MILLER: Yeah, so he was, he was an American. He was born in upstate New York, and he was born in 1851. And always loved nature. And as a little kid, he was kind of mocked for his love of nature. And the way he studied the world, by literally crawling around in the dirt and looking at it, was actually starting to fall out of fashion sort of temporarily in academia, where people were putting more weight on books and recitation of beliefs. And so he couldn't get a job. His first job was a teaching job and his students grabbed the pointer out of his hand and set it on fire. Like, he couldn't get a girl; I mean, he was just, he was as a younger kid, he was beat up. I mean, he was just your classic, nature loving, sweet nerd, and the world would not cut him a break. So that sort of made me fall in love with him, because he just stayed dedicated; you know, the first thing he wanted to do was name the stars. And then he believes that he learned the name of every star, and then he moved on to flowers. And then finally he moved on to fish. And so he's in his early 20s, when he meets a teacher who really changes his life and that's Louis Agassiz, the famous Swiss naturalist who told him, "Study nature, not books". And when he starts studying under the tutelage of Agassiz, his life changes. He suddenly kind of gains this sense of purpose in what he's doing. He gets a great job at Indiana University. He becomes the president of Indiana University. Then he becomes the first president of Stanford. You know, he gets a wife and kids and he starts commissioning with the Stanfords' money, all these expeditions all over the world to collect fish. And as the years go on, he and his team just start discovering hundreds of new species. And I think about like, in a scientist's life, I think to discover one species is, is huge. And to discover over 2,000, at that point, it was like a fifth of fish known to man in his day, so he really helped uncover a massive amount of the tree of life. Like, I think of this whole scaly, lower branches, like a big section of it.

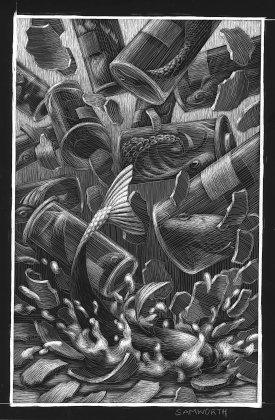

The only fish David Starr Jordan chose to name after himself is the Agonomalus Jordani, a kind of MC Escher of a fish, according to Lulu Miller. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

CURWOOD: So to what extent was this a nice guy?

MILLER: In certain ways, he's full of charm. And from a young age, he says he dedicated his life to the, quote, "hidden and insignificant". He believed that the best clues to nature's plan lied in the unknown, that the true scientists notices everything, and the small. You see that in his life and you see this just profound curiosity. And he's really charming; his, one of the things that made him so great to study is he's really funny, like, he's a funny writer. And he has these odd little goals, like he wants to be able to clasp his hands and jump through them as a little boy, which you just picture. And he, he writes these hilarious satires about people who believe in the occult, and you know, he's kind of mean, but he's really funny. And he does a lot of good. He was really passionate about coeducation, about women getting equal education at Stanford. He was he was a pacifist, he was opposed to World War I at a time that was really unpopular and spoke out against it.

CURWOOD: But?...

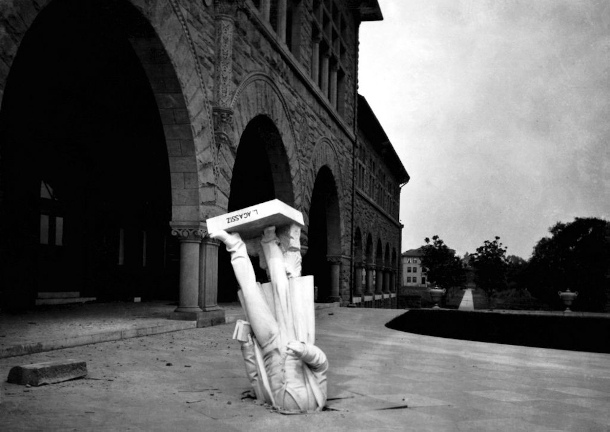

An illustration from the book capturing the moment of destruction during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, when David Starr Jordan’s entire collection shattered on the floor of the Stanford Zoology building. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

MILLER: [LAUGHS] But, there was, um . . . if you got in the way of his goals, he was an utter bulldozer. I mean, he got people fired. There is a lot of evidence that suggests he was involved in a murder; if not in the murder, he was definitely involved in a cover up of a murder. And then the latter third of his life, he was a passionate eugenicist and just could not hear any of the opposition, you know, whether it was the Catholic Church or other scientists calling his ideas, quote, "rot", or judges calling eugenics "an engine of tyranny and oppression". I mean, there was opposition, and he just didn't hear it. Even victims of sterilization themselves saying, quote, "I'm a human being just like you". He just dedicated himself further and further to the cause, and in so doing harmed thousands of lives. So, he's got . . .

CURWOOD: Hmm, well, and being a scientific descendant of Louis Agassiz, who, you know, saw a biological basis for race and all that, that makes a lot of sense.

MILLER: Yes. Yeah.

CURWOOD: One of the things that you point out, you know, of the thousands of species, you said like 2,000 species that he and his team identified, he named one after himself. And you actually went to the Smithsonian to see the specimen. Describe it for me, please.

To add insult to injury, not only did the 1906 earthquake virtually obliterate David Starr Jordan’s precious fish specimen collection, it also toppled the statue of his beloved mentor, the naturalist Louis Agassiz, that had stood just outside the Stanford Zoology building. Lulu Miller observes, “If I were the director of this particular play, I’d tell the set designers to dial it back a notch.” (Photo: Mendenhall, Stanford University, Wikimedia Commons)

MILLER: Ah! Okay. It's a kind of poacher fish called the Agonomalus Jordani. It looks like a dragon, looks like a tiny dragon with big wings, sort of serrated wings. And it almost, its body almost looks like a curling staircase, a spiral staircase. To me it almost looks like an MC Escher drawing where like there are so many corners and curves, but nothing quite lines up. And there's just something a little unsettling about it. It also is really spiny. And so I went to see it, the one; it's called the holotype, which is the very first specimen of a species, so the first physical creature that was ever named; this kind of holy object. And they, they took it; the scientist, she took it with metal tongs out of the jar, and then she placed it in my hand! And I got to hold it with my bare hand. And they're, they're known for being these kind of violent hunters; they'll camouflage themselves with muck and then they'll use those wing-like things, which are fins obviously to, to just strike at incredible speed and get their prey, little crustaceans, before they know what hit them. And so, he discovered so many beautiful, rainbow-colored; crimson; things that glow. And I just I wondered, huh, that was the one in the entire sea, the only one he chose to grace with his name, and I wondered why? I mean, did he see something of himself in that? Did he admire that? Why was that the one.

CURWOOD: That he loved a fish that one might call a monster.

MILLER: Yeah. As a boy, he was always drawing, one of my favorite parts of his archives is it is filled with drawings and doodles, like scientific drawings of flowers, beautiful with ink, and he's not great at it but he's dedicated. They're, they're just, everything's filled in, every single petal, hundreds of them. And then in his later life, he just started drawing beasts, hundreds of them. These, these fantastical beasts that he was making up. He was definitely increasingly obsessed with monsters, I think that that is fair to say.

David Starr Jordan in 1923, at age 72. (Photo: Unknown Author, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Well, I'll leave it to the reader to consider the monster within that you wonder about. Of course, David Starr Jordan, as you write, faced personal disaster after personal disaster. I mean, what's the list? First he loses his big brother in the Civil War to disease, the way most soldiers died in the Civil War, by the way. And then you talked about his collection getting smashed during the earthquake, and . . .

MILLER: And before that, the first collection he built was struck by lightning and burned to the ground. Like, just another detail in his life that doesn't faze him! His first wife died very young after they had had three kids. Then following her death, their baby died. His very first collection you could argue of maps was destroyed by the chaotic force of his own mom. She took all his maps, she thought that what he was doing was a waste of time. She was this Puritan and she chucked 'em. He recruited his one of his best friends from college to come help him on the quest of, he wanted to discover every freshwater fish of North America. And less than a year into their quest, his colleague fell overboard and froze to death while they were searching for fish. I mean, just all around him -- two of his favorite students that he trained in the art of relentlessly pursuing the unknown died while collecting. It felt like his life was plagued by destruction in a fairly uncanny way.

CURWOOD: Now, one of the things you write is that David Starr Jordan had this unflappable optimism about ordering the world, persisting even as all these disasters happen. And he did some pretty horrible things along the way. You know, you raise the questions, ooh, was he involved in a murder? Oh, was, he spent a lot of time with eugenics. So I take it by the end of your book, you're pretty disgusted with David Starr Jordan. [LAUGHS] And you are delighted when you come across a kind of cosmic justice for him. What happened?

“Fish do not exist” because as scientists began to realize in the 1980s, the category of “fish” is evolutionarily nonsensical. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

MILLER: Yeah. So in a certain way it looked like he went to the grave unpunished for his sins and his bad behavior. But then posthumously, there was this incredible discovery, basically, in the 1980s, that fish -- the group, the category of fish -- does not exist. It is not a valid grouping of creatures. So you could say -- it's a category you could make. So you could say, you know, if you wanted to make a group of all creatures that have stripes, fine, that's a group you can call it the stripies. Similarly, fish, you could say all finny things that you know, swim underwater, but aren't whales, aren't mammals. You know, you could say that's a group and you could call it fish. But if you want to actually look at how creatures are related evolutionarily, fish is a totally bunk category. There are creatures such as the lungfish or the coelacanth, which are far more closely related to us, for example, than to their near twin, it looks like, you know, from the outside, a salmon or something.

CURWOOD: And by the way, for those who aren't so acquainted with the Linnean way of classifying, you know, amphibians are a class, mammals are a class. Some would say birds are a class. But fish are not?

_Kristen_Finn.jpg)

“Why Fish Don’t Exist” author Lulu Miller is also a cofounder of NPR’s “Invisibilia”. (Photo: Kristen Finn)

MILLER: Correct. And to me, there's something so poignant about, you know, the universe first strikes with lightning and then with an earthquake and it keeps trying to steal its fish back. Or, you know, this is one way to read his tale. And he keeps trying to overcome it. And then right at the end, the way the universe finally steals his fish is, in a way is by his very own hand, by his own obsession, by his own desire to order creatures. If you were to follow that to its current end, you would see that fish was never, was never an actual grouping at all.

CURWOOD: Lulu, so then how did you come to process this idea that fish don't exist? And, and what does that mean for your life?

MILLER: The best way I can explain it, what I've slowly come to understand is what these scientists are saying is that fish is a gerrymandered category. It's a term we use, it's a proxy that we use to parse the chaos. But it is a way that we keep our sense of superiority intact. And if you want to look more closely at nature, having an openness to the sense that most of our intuitive categories might actually be wrong, can help you see the world more expansively. And so I think, for me, this, this wacky concept that fish does not exist. It's become a mantra in my mind and a reminder, to think about what other categories and hierarchies we may be believing in that we need to re examine.

CURWOOD: Lulu Miller is a cofounder of NPR's Invisibilia and the author of Why Fish Don't Exist. Lulu, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MILLER: Thank you so much, Steve.

Related links:

- Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life

- Lulu Miller’s website

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Over My Head” on Blessed Quietness, traditional/arr.Cyrus Chestnut, Atlantic Jazz]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Anne Flaherty, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. And we say goodbye this week to Candice Siyun Ji and Merlin Haxhiymeri. Thank you both for your hard work! You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And you can find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth