April 17, 2020

Air Date: April 17, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Dangerous Heat in the Gulf of Mexico

View the page for this story

On Easter Sunday, dozens of tornados tore through the southeast United States, resulting in the deaths of over 30 people. These deadly storms came as water in the Gulf of Mexico was three degrees Fahrenheit hotter than the long-term average. Atmospheric scientist Kevin Trenberth of NCAR explains to Host Steve Curwood why warmer Gulf water factors into many of the major storms that affect the United States, including tornados, thunderstorms, and hurricanes. (07:44)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this Earth Day edition of Beyond the Headlines, Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss how street closures in some cities are giving people safer outdoor spaces while practicing corona virus social distancing. Meanwhile, a preliminary NOAA study finds that methane emissions are at an all-time high, so they break down what that means for the climate, and what some of the causes might be. Finally, the dynamic duo looks back 26 years to Earth Day 1994, the day that President Richard M. Nixon died, and discuss his role as a reluctant but effective environmental president. (04:40)

Earth Day Turns Fifty

View the page for this story

April 22nd, 2020 marks the 50th anniversary of the first Earth Day, when some 20 million Americans peacefully rallied for protecting the planet. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Denis Hayes, coordinator of that very first Earth Day and founder of the Earth Day Network, about what April 22, 1970 was like, and how this year’s grand Earth Day plans have adapted to the disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic. (19:08)

Springtime Birding with David Sibley

View the page for this story

A great migration is underway in the northern hemisphere, as migratory birds head north to start a family. Throughout their journeys these long-distance travelers rely on well-stocked pit-stops, like Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Concord, Massachusetts. That’s where Host Steve Curwood meets up with ornithologist David Sibley one fine spring morning, to listen to copious birdsong and discuss the second edition of Sibley’s popular Guide to Birds. (14:32)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Denis Hayes, David Sibley, Kevin Trenberth

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

April 22nd marks the 50th anniversary of Earth Day when some 20 million Americans rallied for the planet.

HAYES: I Looked out at the crowd that had assembled on 5th avenue spilling like 40 -45 blocks on to Central Park and it was literally like looking at the ocean. There were people out beyond the sight horizon, which is when I really began to feel the power of this whole thing.

CURWOOD: Also, the Gulf of Mexico is roughly 3 degrees warmer than usual this spring, which could spell trouble for hurricane season.

TRENBERTH: If it was three degrees above normal as we go into the hurricane season, that's sort of waiting around for any of the disturbances that occur in the right area to enable it to become perhaps more intense and with a lot of heavier rains than would normally be the case.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Dangerous Heat in the Gulf of Mexico

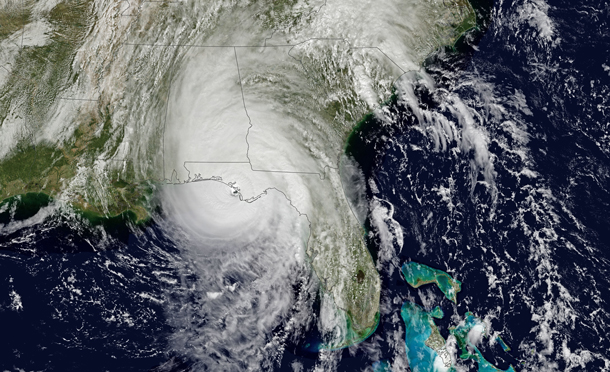

Hurricane Michael in 2018, developing off the Gulf Coast in the United States. (Photo: Joshua Stevens, NASA, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood, at a social distance.

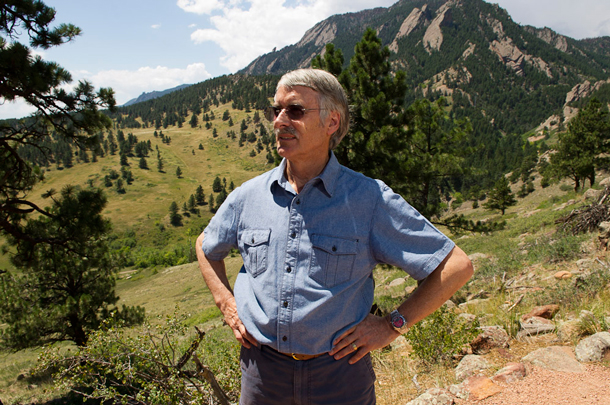

On Easter Sunday dozens of tornadoes tore across the South East of the US, killing more than 30 people. The deadly cluster of storms coincided with warmer than usual water in the Gulf of Mexico, some three degrees Fahrenheit hotter than the long-term average. Science links above-average sea surface temperatures in the Gulf to larger tornado clusters in the southern United States. And higher water temperatures are also a well-known factor in supercharged hurricanes. For more on what warmer Gulf waters might mean this year, I’m joined now by Kevin Trenberth. He is a Distinguished Scholar at the US National Center for Atmospheric Research and a faculty affiliate with the University of Auckland in New Zealand, where he joined us on the line, just before the Easter Sunday tornadoes. Kevin Trenberth, welcome back to Living on Earth!

TRENBERTH: Well, thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: The hurricane season in the western Atlantic Ocean typically doesn't begin until June. What kind of impact would warming waters this early in the year have on the upcoming hurricane season, do you think?

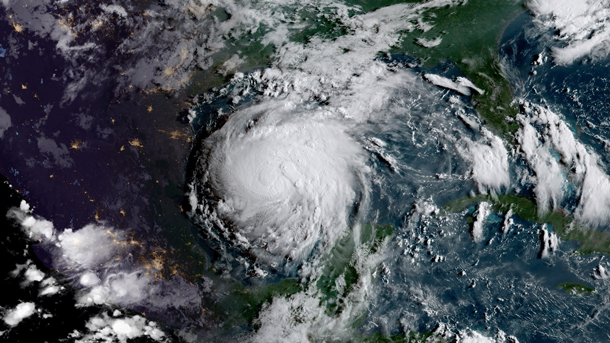

TRENBERTH: Well, as you said, it's a few months to go before we get there. Certainly, if it was three degrees above normal as we go into the hurricane season, that's sort of waiting around for any of the disturbances that occur in the right area to enable it to become perhaps more intense and with a lot of heavier rains than would normally be the case. And the, you know, the best example of that is Hurricane Harvey in 2017. But you know, we've got several months to go before then, and there's, you know, a lot of wind or other activity relating to thunderstorms and even tornadoes could well intervene before then and that helps to wipe out some of that warm water, perhaps.

CURWOOD: Now from what I understand, warm ocean waters can also have an impact on the tornado season inland. How does that work?

TRENBERTH: So, the tornado season has begun in the United States. It runs generally from March through June. So we're into it now. And warmer waters are providing a basic fuel if you like, a warm, moist air, and so that warm, moist air wants to rise and as it rises, the moisture condenses, it creates extra heating, we called latent heating in the atmosphere. This is where the heat comes back from the original heat that went into evaporating the moisture in the first place. And so different kinds of disturbances can tap into this, but they're all trying to move the heat away in some sense. So all of this convection in the atmosphere moves heat from lower levels into the upper part of the atmosphere. And then it gets transported by the jetstream and the circulation to other parts of the world. And some of it can actually radiate to space. So, and so this is one way the atmosphere actually responds. It depends quite a bit on the nature of the disturbances, whether they're a lot of, say individual thunderstorms, or whether there are these larger supercell complexes that can indeed trigger major tornadic outbreaks.

Severe damage to a grove of trees in Livingston, South Carolina following the Easter Sunday tornados. (Photo: National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Back in 2017, there were similarly warm waters in the Gulf and that had some pretty disastrous consequences. Hurricane Harvey with massive rainfall, as you pointed out, that's the same year that had Irma and Maria. So what are the odds of a similarly destructive hurricane season this year, do you think?

TRENBERTH: Yes, so it's going to depend upon the other parts of the Atlantic, because a lot of the disturbances that form hurricanes come off of Africa and they propagate across the Atlantic and then they develop if they find the right environmental conditions. And that certainly includes high sea surface temperatures, and so that was certainly the case in 2017. But the Gulf was exceptionally warm. And Harvey was a very unusual storm that tracked in from the southeast, and then stalled and became a Category Four so close to the land. The land normally helps to kill the intensity of these storms because it feeds drier air into the storms and also because of the friction that's in that area. But Harvey managed to pause in just the right spot, and all of the spiral armbands then just produced prodigious amounts of rain over the Houston area over 60 inches over about a three day period. And you know, the following year in 2018, one of the hotspots in the global ocean was off the east coast of the Carolinas. And so that was the case where Florence developed in that area. And that, you know, produced over 30, 30-to-40 inches of rain in the Carolinas and extensive flooding in that region. So where these hotspots occur can certainly attract activity of various kinds.

The hurricane season in 2017 was worsened by unusually warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico. One of the most disastrous storms was Hurricane Harvey, which was a Category 4 and displaced over 30,000 people. (Photo: NOAA, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So how prepared do you think people are for this year's hurricane season? And how is that preparedness being affected by this novel coronavirus pandemic, do you think?

TRENBERTH: Well, you know, I've watched this with considerable interest and there have been numerous warnings in the past. And the lack of preparedness in the United States and other places around the world is really dismaying, I think, and this is a similar thing for hurricanes. You know, the big warning sign was in 2005 with Katrina and Wilma and Rita, you know, all these category five storms that occurred then and there was considerable concern. And I went to some meetings, which had heads of states of some of the islands in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, following that, and correctly, they were very concerned about two things, the rising sea level, and hurricanes, stronger hurricanes. So the concern was certainly there. What has been disappointing from my standpoint is how little preparedness seems to have developed and this was brought home in 2017 with Harvey, the total lack of adequate drainage systems and building in wrong places and building structures that weren't prepared in Southern Texas. Also, Irma went right up Florida. And then Puerto Rico, the lack of preparedness in Puerto Rico is astounding, appalling. And in fact, even places like Cuba, were somewhat better prepared than Puerto Rico was. And so, you know, the warnings have been there, why isn't there more effort to prepare for the sort of thing scientists have more or less guaranteed, but you can't say, you know, exactly when. And so this is the paradigm for global warming. You know, global warming is coming. One of the differences with global warming is that with the COVID-19 virus, we think we can develop cures, we can develop a vaccine. But once global warming is here with us, there's no vaccine that is going to be developed that will make that go away. So I think this is a warning sign, and I certainly hope the governments around the world and the peoples around the world can take account of that.

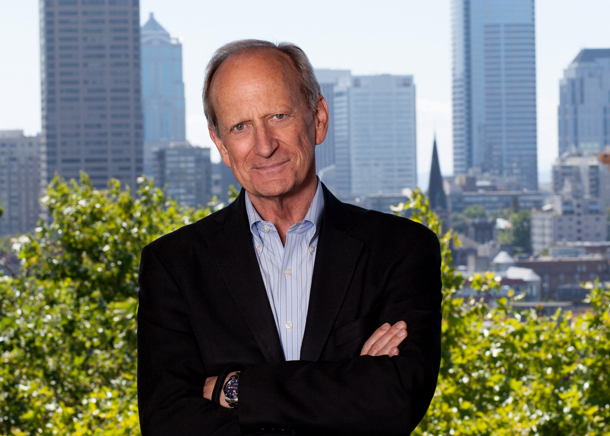

Kevin Trenberth is a Distinguished Scholar at the United States National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and a faculty affiliate with the University of Auckland in New Zealand. (Photo: Courtesy of Kevin Trenberth)

CURWOOD: Kevin Trenberth is a distinguished scholar at the US National Center for Atmospheric Research and an affiliate member of the faculty at the University of Auckland. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Kevin.

TRENBERTH: Oh, you're most welcome.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “Abnormally Warm Gulf of Mexico Could Intensify the Upcoming Tornado and Hurricane Seasons” This detailed article has references to a number of scientific studies relating storm activities and higher water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico

- More on Kevin Trenberth

- Science Alert | “By the Way, Antarctica Just Experienced an Unprecedented Summer Heatwave”

[MUSIC: Childsplay, “Mothers Of The Disappeared” on Waiting For the Dawn, by Hewson, Evans, Mullen, Clayton/Hanneke Cassel, Childsplay Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Boston is one of three major American cities, along with Oakland and Minneapolis, to experimentally close certain through-streets to give more room to cyclists, walkers, joggers, and the one man who has been walking around Living on Earth intern Isaac Merson’s neighborhood with a sousaphone. (Photo: rik-shaw 黄包车, Flickr, CC by 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, it's that time of the program when we take a look beyond the headlines with the indomitable Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with environmental health news that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And he's on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, what's going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. Well, as we deal with the COVID-19 crisis, it's justifiably dominating all the headlines. But there are some little things happening that we ought to notice, like an inventive thing that at least three major American cities are trying out to help their populations cope.

CURWOOD: And that would be?

DYKSTRA: Well Boston, Minneapolis, and Oakland have temporarily banned through traffic on certain streets, giving hikers, joggers, walkers and bicyclists, a little extra elbow room so they can get out and maintain the six feet of social distance.

CURWOOD: And Peter, I'm going to make a prediction that those bicyclists having had a chance to get around without getting so threatened by cars are going to really push back when this virus thing is over to have more access.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, and some of those empty streets have another positive benefit. Not that it makes up for all of the tragedy and all of the death and suffering of Coronavirus. But the air in American streets and around the world is much, much clearer than it normally is. There are some other cities like Washington DC, that considered doing the same thing but rejected it. Washington DC Mayor Marion Bowser said there needs to be limits on how we encourage people to gather outside. But the clean air and the decline of as much as two thirds or more vehicle traffic is one little positive in all of this.

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter. So what else do we have this week?

A fracking job underway in the Bakken formation of North Dakota. Fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, is a process by which oil and natural gas are extracted after underground rock formations are fractured by pressurized water. While researchers have identified that there is a significant amount of methane released during this process, the true extent is still uncertain. (Photo: Joshua Doubek, Wikimedia Commons, CC by S.A. 3.0)

DYKSTRA: Methane levels, according to a preliminary NOAA study are at an all-time high. Methane of course is a far more potent heat-trapping greenhouse gas than CO2. Some believe it's 80 times as potent as carbon dioxide, even though it doesn't last as long in the atmosphere. It does a lot of damage in the short term.

CURWOOD: Yeah, the short term being 1020 years, which is when we have to get this right. So where's all this methane coming from?

DYKSTRA: Some of it comes from an increase in fracking. There are mostly untold methane releases from fracking, the wildly popular method of oil and gas drilling that's taken hold and changed the face of the oil industry. But one of the primary sources is the melting of Arctic permafrost and methane released from vegetation that's been trapped and frozen for as much as 10s of thousands of years. Also releases from the ocean: methane from decaying sea life is a big contributor as well. It could be one step back even as we take one step forward in battling to control climate change.

CURWOOD: It's a very scary one, Peter, because as more methane comes off the permafrost, it'll make things warmer, which will then make more methane come off the permafrost, we could stop fracking, but I don't know how we stopped that.

DYKSTRA: Right.

CURWOOD: What do you see when you look back in history?

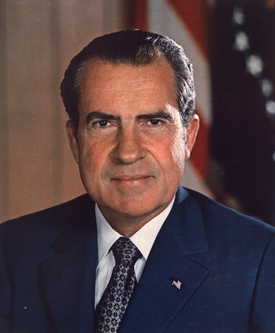

Richard M. Nixon, 37th President of the United States, had a wide-ranging legacy of signing environmental policy into law, despite mixed personal feelings about environmentalists (Photo: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: Well, as we've discussed a few times before in the show, there's no president that has been more environmentally active, not just in our lifetimes, but in history than Richard Milhouse Nixon, the guy that signed the Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and on April 22, 1994, President Nixon died on Earth Day.

CURWOOD: You know, I'm not sure that Nixon would care to be remembered as the environmentally active president. I don't know how much he really bought into it.

DYKSTRA: Well, what he might say is I am not a tree hugger. And actually what he did say in a meeting with the big three automakers' CEOs is that environmentalists wanted to quote, live like a bunch of damn animals. They can't take away that impressive string of environmental achievements, including the founding of NOAA, the founding of EPA all happened on Nixon's watch, and he died on Earth Day in 1994.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news that's ehn.org. And dailyclimate.org. Happy Earth Day, Peter and stay safe,

DYKSTRA: Happy Earth Day and everybody stays safe and healthy.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories that the living on earth website LOE.org

Related links:

- Read about Oakland’s “Slow Streets” program here

- Learn more about the global trends in various atmospheric greenhouse gases on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) website

- Click here to learn more about the first Earth Day and the events surrounding it, when Richard Nixon happened to be president

[MUSIC: Bill Frisell and The New Quartet, “Keep Your Eyes Open” on Groundwork-Act To Reduce Hunger, by Bill Frisell, a Groundwork Production on Hear Music]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Bill Frisell and The New Quartet, “Keep Your Eyes Open” on Groundwork-Act To Reduce Hunger, by Bill Frisell, a Groundwork Production on Hear Music]

Earth Day Turns Fifty

Earthrise is the image of planet Earth taken from the Apollo spacecraft during the first manned mission to the moon, led by NASA in 1968. This event has continuously sparked interest in the beauty of the earth, and the possibilities brought forth by science. (Photo: NASA, www.earthday.org, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Back during the Vietnam War the United States was rocked with sometimes violent anti-War protests including in the Spring of 1970. So there was a sense of relief when some 20 million Americans peacefully marched and rallied on April 22nd for the very first Earth Day. And for that moment, people from just about all parts of the political divide came together to call for a cleanup of our planet.

[MUSIC: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Youg, “Ohio” on So Far, Atlantic Recording Corp.]

CURWOOD: But the truce over public demonstrations would end less than two weeks later when Kent State University students protesting the US bombing of neutral Cambodia set fire to an ROTC building, and National Guard soldiers later shot and killed 4 unarmed student protestors.

[MUSIC: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Youg, “Ohio” on So Far, Atlantic Recording Corp.]

CURWOOD: But thanks to that first Earth Day, the modern environment movement had come alive. Joni’s Mitchell’s environmental anthem "Big Yellow Taxi" came out the same month as the first Earth Day.

[MUSIC: Joni Mitchell, “Big Yellow Taxi”]

MITCHELL [SINGING]: They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

With a pink hotel, a boutique

And a swinging hot spot

Don't it always seem to go

That you don't know what you've got til its gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot . . .

CURWOOD: As well as Earth Day, 1970 would see the creation of the EPA, and the passage of major laws, including the Endangered Species and Clean Air Acts. Denis Hayes was the national coordinator of that first Earth Day, which is now celebrated in nearly every country on earth and considered the largest secular holiday in the world. He went on to found the Earth Day Network. He joins me now. Denis Hayes, welcome back to Living on Earth!

HAYES: It's always a pleasure, Steve.

CURWOOD: So Dennis Hayes, take us back to April 22, 1970. That very first Earth Day, beginning in the morning, where were you?

HAYES: Well, I rolled out of bed in my decrepit little basement one-room apartment on Dupont Circle and walked down to the National Mall before daybreak, where we had a daybreak ceremony with Native Americans who were welcoming the sun; then raced off, jumped on a plane and flew up to New York. And after weaving through massive tangled traffic, got to the stage where they directed around Fifth Avenue, where I had a speaking role and climbed up really high and I, you know, it's 50 years ago, I can't really tell you the height, but my sense is 60, 70 feet at least, and looked out to the crowd that are dissembled on Fifth Avenue spilling like 40, 45 blocks towards Central Park. And it was literally like looking at the ocean. There were people out beyond the sight horizon, which is when I really first began to feel the power of this whole thing.

CURWOOD: So how many folks do you think were there?

Earth Day Network’s mission is to diversify, educate and activate the environmental movement worldwide. (Photo: Nick Kenrick, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

HAYES: Well, I would guess upwards of a million people in Manhattan, and the estimates from the wire services for the country as a whole -- and of course, nobody's counting noses because Earth Day was in literally every city, every town, every crossroads in America -- but the generally accepted number was 20 million people, which was almost one out of every 10 Americans participating. Earth Day 1970 was a great surprise, our aspirations when we started out -- the very start was to have teach-ins on college campuses, which turned out not to work in part because college campuses weren't at that point interested in the environment and teach-ins were passé. And when we moved away from environmental teaching, renamed it Earth Day, took it out into communities, the hope was to have something that was equivalent to say the Vietnam moratorium, or the March on Selma or the March on the Pentagon, a one-time event that would take some important issue, gather enough people that it would generate news coverage and help educate the public about that issue. When it instead turned out to be something that wasn't just in six or eight cities, but in literally dozens and dozens of cities in every other sized community across the country, where we had an estimated 2000 colleges and universities that had something going on. It was just massive. And, one, it was exciting, because it was so much larger than we'd anticipated when we began. And then in retrospect, it became unique in that unlike the March on the Pentagon, it was not a one-time thing. It came back again without much-centralized organizing. In fact, I was trying to kill it in 1971, because we knew it would have to be smaller than in 1970. And that would feed into a media narrative that this was, in fact, a fad. And the support is declining because you can't get 20 million people time after time, out. But then it went on to '72 and '73. And by the time we got to 1990, it was established as a, it's almost a national holiday, it appears on calendars, teachers put it in their lesson plans, and everybody just expects it every year.

CURWOOD: You're often quoted with a line that you gave at the rally in Washington. I wonder if we could hear it again.

HAYES: Sure. 1970 came out of the 1960s. So there were a lot of issues parading across the American political stage, including dominantly, the anti-war movement, the civil rights movement, the beginnings of the feminist movement, huge cultural issues around the Summer of Love in San Francisco and Woodstock, which didn't play that well in the middle of the country. And there was some tendency in some quarters to think this environmental thing is another little thing that's coming across and it's just going to be a passing fad. And I made the case fairly strongly that "if this is a fad, it's going to be our last fad."

CURWOOD: So let's put this in some historical context. Denis Hayes, tell me more about the oil spill off the California coast near Santa Barbara in 1969.

HAYES: Sure, and two Earth Days actually had oil spill sort of feed-ins. In 1969, the first big oil spill to really capture public attention in the United States took place off of a fairly well-heeled California community with white sand beaches that just turned into a tarry mess. And there was a huge citizen uprising, but unlike many which were in communities of color, or were in communities that were sort of middle class, this was a bunch of rich people, on the streets demanding, Get the Oil Out, an organization called GOO and that was something that really captured everybody's attention in that, one, it had all these poignant scenes of sea life that was being covered with oil and suffocating. But the other was that it brought home that these pollution issues were something that could capture any part of American life, even a place like Santa Barbara. Then 20 years later, as we were going into the 1990 Earth Day, which was the first time we took it international, then we had the Exxon Valdez, the previous year off the coast of Alaska with a much larger oil spill. I suspect there were some people that thought that I was timing Earth days to follow major oil spills because the two first really big ones were in that context.

CURWOOD: How accurate is it to say that Wisconsin Democrat, Gaylord Nelson, the senator was inspired to create Earth Day upon seeing that huge lick of oil off of Santa Barbara there?

HAYES: Yeah, I think it certainly was one of the starter engines in some of the, what should we call them, the creation myths from the beginnings of this; Gaylord, the idea occurred to him as he was flying over Santa Barbara. I think the idea actually first occurred to him in some conversations with Fred Dutton, the political consultant, but you tell these things in the ways that are the most dramatic. And clearly, the Santa Barbara oil spill along with Silent Spring, and the Population Bomb, and the quality of air in Pittsburgh and Gary and Los Angeles, and the Cuyahoga River catching on fire and the predictions that the Great Lakes were dying, and, you know, all of those things were coming together as separate strands and Gaylord had a sense that all of them, if packaged together could actually be something of some real political input. And he was, I think, certainly the first major politician to have that sense.

Denis Hayes coordinated the first Earth Day in 1970. He also founded the Earth Day Network and expanded it to more than 180 nations. (Photo: Courtesy of Denis Hayes)

CURWOOD: Now, why do you liken environmental initiatives to a global war, Denis?

HAYES: When you're trying to bring people together, nothing brings them together more than a common enemy. If you have a 9/11 and then suddenly America rises up in unison, or with Pearl Harbor. With regard to environmental issues globally, we've had great difficulty doing that in an era, particularly of mounting nationalism. And what we've been trying to do with environmental issues as much as we do with a pandemic, is to view this as a threat to Homo sapiens, where the entire species has to come together to protect itself.

CURWOOD: So today, 2020, 50 years after, what is the focus of Earth Day, what are the initiatives that are now being emphasized?

HAYES: The core purpose of the 50th anniversary of Earth Day was to finally take the climate emergency seriously, not as a subject for additional reports, not as a subject for additional international conferences, not to spin our wheels with voluntary activities, but to take something akin to the Green New Deal proposed domestically and take that out internationally with people around the world going out into the streets in mass crowd demonstrations. Everything from Pope Francis who'd agreed to address a very large crowd at St. Peter's Square to things in Rio de Janeiro, things in Kolkata. We hoped to have 750,000 people on the National Mall in Washington DC, to stand there and just demand that we finally get serious about this issue and move boldly, not with a $15 a ton tax on carbon, but it was initiatives that will really change the game dramatically. The downside is we spent two years organizing these things. And when COVID-19 reared up and quickly, within a month spread to be a global phenomenon. Literally, everything that we had spent two years organizing became illegal. I mean, where we wanted to have 750,000 people on the National Mall, it would now be illegal to have more than 10. So it has been a hugely frustrating experience. Nonetheless, it's our belief that the time is right, the student climate strikers around the world have certainly captured public attention; efforts out of the Paris accord, although repudiated by Trump for the United States, and hence sort of gutted will be pulled back together and that will perform a little bit more. And then, of course, there's simply all of the events that Mother Nature is bringing us from the wildfires in Australia to the rising seas that are flooding repeatedly, places from Miami to Hawaii and the United States. It's coming together now where there's not the ambiguity that was attending climate change in 990, when it was done, mostly discussed as two lines passing on a graph 20 years in the future. Now those lines have crossed and the real world is demanding attention.

CURWOOD: Now the 50th anniversary of Earth Day was entitled Earth Rise 2020. Without the ability to have the massive crowds together on Earth Day, how will you bring people together in that moment?

HAYES: We're going to have streaming events. And well, Pope Francis won't be at St. Peter's Square, he'll be giving his little video to us as well as a bunch of other leaders from various sectors, political, scientific entertainment, sports, bringing brief messages interlaced with hopefully some prominent musicians playing entertaining music out of their living rooms into video, and maybe some film clips, some animations, stuff that pulls people together and carries an educational message forward. And the people that the Earth Day network is just busting their tails to try to make this just as effective as possible. candidly, there just isn't any potential substitute for 750,000 people on the Mall in Washington DC in terms of political impact, so we're going to do our best to salvage it. But the most important things will probably be in the months after that is hopefully COVID-19 fades from absolutely dominating all news coverage, and we try to carry on what was already beginning to happen, which is that climate would become an ever more important political issue voting issue in the United States.

Earth Day 2020 events are scheduled to happen virtually, due to the coronavirus outbreak. (Photo: Kevin Turner, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: What does COVID-19 tell us about the climate, Denis?

HAYES: Well, if I move to uncharacteristic optimism, you could think that COVID-19 shows pretty clearly the interdependence of the world and the need for some kind of global authority like the World Health Organization that will summon expertise until individual nations what they must do on behalf of all of humanity, that has a lot of analogies to climate change.

CURWOOD: So you talk about Earth Day becoming more and more political and these times focusing on the urgent need to deal with the climate. How can you get people to change their minds? How can you get people to focus on this who right now dismiss it?

HAYES: The very strange things about the environmental movement is that there is a division within it between people who are interested in politics and policy and people who are interested in behavior and lifestyle and consumption. And they tend not to cross over very much. One reason why we had a Dirty Dozen campaign was that the lifestyle people did not want us to endorse anybody. And the political people said, Hey, you had 20 million people in the streets and you're going to ignore an election. And so the compromise was we would not endorse any political candidates, but we would oppose political candidates because that allowed us to pull both halves into that initiative. On climate, there's a similar sort of thing that people who focus on international agreements that focus upon neoliberal economic solutions, taxes, cap and trade. People who focus on the Green New Deal, tend, in general, to be a little bit dismissive of the people who are saying, you ought to be paying attention to your diet and eating a little bit lower on the food chain, you need to pay attention to what car you drive and what kinds of appliances you buy, and how much you travel around in jets because you multiply that stuff times 300 million Americans and seven and a half billion people, and it really adds up. And those are choices you can make, the government can't stop you from making, I tend to come right smack down on top of both. You have to be doing all of those things. And one of the messages this Earth Day, although it intended to be principally political is going to be what you can do as an individual. And there are lots of reasons for that. One is the actual impact of those in the aggregate. Another is that when you get people to actually behave in some fashion, they work harder on behalf of the beliefs and the values that underpin that action. That's something religions discovered 2000 years ago. And finally, when you're trying to persuade people on the other side are people who are undecided about something but you are walking your talk you are living the values that you were trying to portray to them, they'll view is somebody that lives with integrity. And one of the things that has hurt us a little bit has been people who are hypocrites, who fly in their personal jets to a rally to give a speech on energy conservation. And people come because they're celebrities and their crowd magnets, but they don't take their content that seriously. Because if you're serious, you don't fly your individual jet to that rally.

CURWOOD: One of the ironies of Earth Day at age 50, is that, this year, the Earth is the quietest that it's been probably in the last maybe even 50 years. With so many people in the industrialized part of the world, staying inside, with so much industrial and other activity stopped or tamped down. People are talking about hearing birds in Manhattan. What do you think of the Earth herself perhaps taking this moment to celebrate herself?

HAYES: You know, there is something to be said for the powerful role that Mother Nature is playing and that you can ignore her for a little while, but sooner or later she will assert herself. And that's... pandemics are clearly one of the ways that that happens. A really interesting thing about COVID-19 and its impact on the industrial world is whether it will lead, not to some temporary reductions in carbon emissions and air pollution, but whether there will be any kinds of permanent behavioral changes. We are all working from home. And some of us are able to spend more time with our families, we're recognizing that the commute whether it's in a car or a bus, or mass transit is wasted time, and it's nice to be not having to waste that time. So let's say that in America, of those people who are not in jobs that require them to be at the restaurant or at the hospital, but in an office where some of that work could be done at home if each in the future just stayed home one day a week and worked from home that would reduce the commuting by 20%, and the pollution by 20%, and the energy consumption by 20%. And give them free time and you'd be doing something more productive with. If we're all eating at home instead of eating in restaurants. And some of us are planting gardens that hadn't had gardens before. Is that something that will continue? It might be leading to a healthier population and guaranteed food where you don't cook more than you're actually going to be eating. And if there is some leftovers, you can just stick them in the refrigerator, so there's less food waste. They can be genuinely organic and local because they're out of your own backyard. I think a great many people are finding relaxation relief, a lack of stress, despite the stress of the disease itself, coming out of the public response to COVID-19. And it's possible that there will be some beneficial changes that will come and will be permanent.

CURWOOD: Denis Hayes was the national coordinator of the first Earth Day back in 1970. And he's presently president of the Bullitt Foundation, environmental philanthropy in Seattle. Dennis, thanks so much for taking this time with us.

HAYES: Steve, it's been a pleasure, all 30 years that we've been doing this.

Related links:

- More about Earth Day 2020

- More about Bullitt Foundation

[MUSIC: Joni Mitchell, “Big Yellow Taxi”]

CURWOOD: Coming up – An early morning birding trip to some wetlands with the popular bird guide author David Sibley. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt, and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Thelonious Monk, “Dinah (Take 2)” on Solo Monk, by H.Akst-D.Lewis-J.Young, Columbia Legacy/Sony Music Entertainment]

Springtime Birding with David Sibley

David Sibley’s hand painted portrait of a Mute Swan and cygnets. (© David Sibley)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

In this season of Spring and Earth Day, we look back at some of the stories that have inspired us. So today we take you back to five o’clock on a May morning in 2014 when we headed out to the Great Meadows National Wildlife refuge in Concord, Massachusetts, to meet up with David Sibley, author of the popular Sibley’s Guide to Birds. These marshes, lakes, and woodlands are pit stops for migrating birds heading north and home for local birds looking to find a mate, and as sunlight started to flood the sky, the dawn chorus filled the face of David Sibley with a smile.

[BIRD CALLS]

CURWOOD: So, who are we listening to here?

SIBLEY: Ahhh, we're hearing Northern Cardinal, Blue-grey Gnatcatcher, Warbling Vireo, Red-winged Blackbird, Swamp Sparrow, Yellow Warbler, Common Grackle, Catbird, Common Yellowthroat, Canada Goose.

CURWOOD: Gee, I think that you probably just doubled my life list for around here.

[LAUGHS]

SIBLEY: I’m hearing a Northern Waterthrush singing in the bushes right there. That chirping sound descending in pitch.

[CALLS OF NORTHERN WATERTHRUSH]

CURWOOD: A Northern Waterthrush. Let’s look at your book. Where are we to find a Northern Waterthrush?

SIBLEY: It’s one of the warblers. So it’ll be...

CURWOOD:...in the warbler section back here.

[FLIPS THE PAGE]

SIBLEY: Right here.

CURWOOD: You’ve added something I didn’t see before in your other works which is a description of what the bird sounds like. Can you read that?

SIBLEY: A song of loud of emphatic clear chirping notes generally falling in pitch and accelerating loosely paired or tripled with little variation; called a loud hard sprik rising with strong K sound; flight call a buzzy high slightly rising zip.

An early morning in the Great Meadows National Refuge, located in Concord, Massachusetts. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: Your descriptions are almost the way people describe wine, with a little bit of this flavor and a hint of that and all that.

SIBLEY: Yes, we do. It’s so difficult to describe in words what a bird sounds like. You end up using words like mellow and rich and liquid and sharp and it does just sound like the descriptions of taste. [LAUGHS] If the words are used consistently and used repeatedly you kind of get a sense of what each one means and you’ll learn that yes, that thrushes tend to have a liquid sound, and orioles and robins, their voices have a rich sound. It’s fun to try to come up with words to describe all these sounds.

CURWOOD: So your first book, really, so many folks see that as a gold standard for a birding guide. So why do another?

SIBLEY: As soon as the first book went to the printer back in 2000, I started taking notes and gathering information about things I wanted to change, or new things I had learned. I look at those paintings and think I could do this or that a little bit better, or add details, or add new illustrations to show different things.

CURWOOD: Well, let’s take a step out into the meadow.

SIBLEY: Alright. Let’s head down this path through the marsh here.

[FOOTSTEPS ON DIRT PATH, BIRD SONG]

SIBLEY: So I’m hearing a Common Yellowthroat, Yellow Warbler, Grey Catbird, Red-winged Blackbird singing.

[SONG OF INDIGO BUNTING]

Up above us there’s an Indigo Bunting singing up in the Maple right there, that high pitched sound, and every note is repeated, every phrase is repeated. The Indigo Bunting is a migrant. They don’t normally nest right here. So we can be confident that that bird probably just arrived last night. It probably flew up from the south last night, dropped in here sometime early this morning, and now it’s checking things out, gets up to the top of the tree and sings a little bit to see if anyone answers, and it’s kind of assessing the area to figure out if this is a good place to stay for the summer, and I think the answer’s going to be no. It’s too wet for Indigo Buntings. They don’t nest here, so it’ll move on. Maybe it’s already moved on. I don’t hear it anymore.

Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb and Steve Curwood go birding with guide David Sibley. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

This time of year, all the birds are singing, and it’s so much easier to walk through an area listening and hear what’s around, and it’s possible to identify every species, essentially every sound can be identified.

[GEESE HONKING]

SIBLEY: One of the things about birdsongs is their ears work a lot faster than ours. Their ears and their brain processing of sounds works a lot faster than we do, so they’re hearing an incredible amount of information more than we do. If you take a bird sound and slow it down to about a quarter speed, then you start to hear the kind of detail they’re hearing.

CURWOOD: So why is it that birds are, well, singing the loudest in the morning?

SIBLEY: I think the song in the morning is mostly kind of a checking in with the neighbors. Male birds sing to kind of defend their territory, to mark the edges of their territory. So they’ll circle around to perches at the edge of their territory and sing from those spots and their neighbors, they’ll recognize the sounds of their neighbors. They recognize each other. So the morning song is kind of just an announcement that, “I’m still here. Are you still here? Yes. OK. Territorial boundaries still enforced? Yes. OK.”

CURWOOD: And what about the migrants?

SIBLEY: Migrants, they might be singing to sort of test the area, to see if they get a response, to see if there’s a female nearby that might respond to the song. But mostly, it’s probably just hormones. It kind of goes back to the old poetic thing about birdsong just being an outpouring of joy, the uncontrollable urge to sing with the dawn of the spring morn, and these migrants, they’re near their breeding grounds here, they’re heading north, they’re just about to enter this phase of life where they’ll find a mate, they’ll set up a territory, raise young, and they just can’t control themselves. They sing at dawn.

CURWOOD: One of the things that has certainly changed about birding is our awareness that the climate is shifting, and that means that birds are shifting. How do you account for that when you do a habitat range in your books?

SIBLEY: In the 40 plus years since I’ve been birding, starting in Connecticut in the 1970s and now in Massachusetts, I see really big changes in birds. Some species have increased tremendously like Canada goose, Wild turkey, Red-bellied Woodpecker. Some of those species are southern birds that are moving north, and some of that’s probably due to climate change, but there are all kinds of other things going on in bird populations, and a lot of species have declined. But it’s about equal numbers of sort of winners and losers in the last 40 years, so over that span of time, 40 years, the maps and the bird guide would have changed a lot for probably 10 percent of the species.

CURWOOD: 10 percent of the species in different places 40 years ago. What accounts for that, do you think?

SIBLEY: Mostly it’s changes in habitat. The big change here in the northeast is that, well, 100 years ago it was almost all farmland, there was the very little forest. And 40 years ago, we were just coming out of that, and now, a lot of farms have been left to grow up to forest and all the suburbs that were built in the ‘50s and ‘60s with trees planted then, the trees are now 60 years old and big enough to support a lot of forest birds, the ones that can coexist with people like robins and bluejays and grackles and Wild turkey and even birds like Pileated woodpecker. It was incredibly rare in Connecticut when I was a kid in the ’70s, and now they’re pretty widespread and found in the suburbs.

CURWOOD: Indeed, and hungry in the suburbs too.

SIBLEY: Yes, sometimes unpopular when they look for food in the siding your house, but they can do a lot of damage. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: So you’re an ornithologist, you’re a writer and an artist. And you hand-paint every one of these bird pictures in your guide yourself. Tell me about the process and why you do it.

SIBLEY: When I’m in the field, I’m watching birds, I’m studying shape and posture and doing pencil sketches and then, so I have years and years, thousands and thousands of pencil sketches from the field. When I’m back in the studio I get all of my pencil sketches and I use photographs as reference to get all the details right, and I work on paintings in the studio. For me, and we’re really lucky in this time now, and it’s really in the last 15 years that photographs have become so numerous, to have so many photographers doing such good work and everything’s available on the internet that for the work that I do, I can find hundreds of photographs of every species. Illustrators like Peterson had to use specimens for their reference material.

CURWOOD: Yes, I guess Audubon famously shot everything he drew.

SIBLEY: Yes, he did, and he was traveling through the woods with nothing but a shotgun and his painting supplies. He didn’t have binoculars, he didn’t have cameras, nobody had a camera. There weren’t even books he could carry with him to help identify the birds. It was just him and his paintings.

Sibley points out a songbird. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[SOUNDS OF SWANS FLYING]

SIBLEY: A pair of mute swans flying by.

CURWOOD: Not so mute.

SIBLEY:[LAUGHS] Yeah, that sound is their wings. They do make vocal sounds also. They’re not entirely mute, but that sound is produced by their wing feathers. Just sort of humming through the air with each wing stroke.

CURWOOD: So, I have to ask you, what got you hooked on birding?

SIBLEY: I have always been interested in birding. My father’s an ornithologist so I’m sure that had something to do with it.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I guess so.

SIBLEY: But, yeah, birding was a part of what our family did, I just really enjoyed it, the birding and I was always drawing birds also.

CURWOOD: So when did you realize that, well, this would be the work part of your life?

SIBLEY: As a young teenager in Connecticut, I was going out on the weekends with people from the New Haven bird club and watching birds, identifying birds, learning about them. People were supportive of my interest in birds and my drawing, very encouraging. And Roger Tory Peterson who had illustrated the most popular field guide at the time lived about 20 miles away. I met him a few times when I was a kid, and to have him flip through a few pages of my sketchbook and look at it and say, “Oh, these are very nice. Keep it up.” And I think I grew up with the idea that writing a field guide was a perfectly viable career choice. I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t interested in birds.

CURWOOD: Well, that’s a better way to grow up birding than being dragged out at five in the morning to stand in the cold.

SIBLEY: [LAUGHS] We did plenty of that too.

CURWOOD: There’s something about birding, which even if you don’t want to, it kind of grabs you.

SIBLEY: Yes, and the popularity of birding has increased so much in the last 40 years. When I started out in the ’70s, it was rare to see another birdwatcher, and now, you go to a place like Great Meadows here, the parking lot at times will be filled with cars of birdwatchers. I think it’s just a desire to connect with nature, and birdwatching is just away, it’s an excuse to set the alarm for 4:30 in the morning and go out even if it’s raining or windy, and get outdoors and just experience that. And it’s not so much about the birds, the birds are kind of the hook, the pull that gets us out there, but to a birdwatcher, it’s as much just the experience of being outdoors and feeling the change in weather and seeing the seasons change and being aware of those patterns. I think that's the real draw.

CURWOOD: David Sibley, thank you so much.

SIBLEY: Thanks, it's been a pleasure. What a great morning.

CURWOOD: For 2020 David Sibley has published a book called “What It’s Like To Be A Bird.”

Related links:

- Sibley Guidebooks

- More on David Allen Sibley’s most recent book, What It’s Like to Be a Bird

- David Allen Sibley also creates drawing videos for Audubon

- The #sketchwithsibley tag on Instagram

[MUSIC: Bennett Hammond, “The Emerald Necklace” on The Muddy River Suite, by Lorraine Hammond. Snowy Egret Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts, and Google Podcasts- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Happy Earth Day and Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth