June 28, 2019

Air Date: June 28, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump Clean Power Plan

View the page for this story

The US EPA recently finalized the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule to replace the Clean Power Plan of the Obama Administration. The ACE rule is expected to be challenged in the courts, as it does little to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and could result in up to 1,400 additional deaths from air pollution each year. Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau tells Host Bobby Bascomb about the legal road ahead for the ACE rule. (08:35)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

For this week's trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb discuss how Republican members of Oregon's State Senate walked out to avoid a vote on climate change legislation. Then, the pair discuss Cold War-era spy satellite data that scientists are using to estimate current ice and snow level loss in the Himalayas. Finally, a look back in history to the relocation of Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin to evade a flooding river. (04:30)

Resilient Corals Get a Helping Hand

View the page for this story

More than half the world’s coral reefs have died in the last few decades and scientists predict that as many as 90 percent could die off this century as the ocean chemistry changes and temperatures rise. But some coral populations are actually thriving in warmer waters, and scientists are working to speed up natural selection by propagating these resilient corals. Joanie Kleypas, founder of the nonprofit Raising Coral Costa Rica, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about her work. (08:46)

.jpg)

Repairing Puerto Rico’s Corals

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Roughly 10 percent of Puerto Rico’s corals were broken and damaged by Hurricane Maria in 2017. But, as Host Bobby Bascomb reports, marine conservationists are finding ways to give corals a fighting chance by reattaching healthy fragments. (08:08)

BirdNote®: The Auklet’s Whiskers -- Not Just for Show

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Showy feathers on birds are often solely useful for attracting a mate. But as BirdNote®’s Michael Stein explains, the Whiskered Auklet’s feathery whiskers have another function. (01:48)

Freshwater Under the Sea

/ Joseph WintersView the page for this story

Most of the world’s aquifers, like the Ogallala of the Central Plains, are under dry land but researchers recently discovered an enormous source of fresh water under the Atlantic Ocean. Living on Earth’s Joseph Winters explains. (02:03)

Turning Backyards Into Pollinator Havens

View the page for this story

Recent studies show insect populations are in sharp decline, and as many as 40% of insects may be facing extinction in the coming decades. That includes critical pollinator species such as bees, which play an essential role in ecosystems as well as our food system. Now lawmakers in Minnesota have approved a new program that pays homeowners to convert their lawns to pollinator-friendly habitat. Host Bobby Bascomb talked with Sarah Foltz Jordan, a Senior Pollinator Conservation Specialist with the Xerces Society, about what people can do to make their own yards more pollinator-friendly. (09:37)

The Mighty Condor

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

The California condor was on the verge of extinction due to lead poisoning. Then the US Fish and Wildlife Service stepped in. Now, with more than 400 birds in the wild, the condor is making a big comeback. As Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender reports, when it comes to Condors, big is the operative word. (03:09)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Sarah Foltz Jordan, Joanie Kleypas, Pat Parenteau

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender, Michael Stein

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb

The Trump Administration has released its replacement for the Clean Power Plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

PARENTEAU: The Clean Air Act requires the use of the best system of emission reduction when it comes to carbon pollution. This proposed energy rule of the Trump Administration is almost the worst emission reduction plan, and it's a very expensive plan that won't do very much at all.

BASCOMB: Also, how to help struggling insects by creating a pollinator friendly yard.

JORDAN: The most important thing we all can start doing is thinking about our own landscaping decisions, not just in terms of our own aesthetics, and you know, maybe the status quo, but also thinking about these decisions in terms of how these plants that we choose to put into our yards can, in turn, support the ecosystem.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump Clean Power Plan

At best, the Trump Affordable Clean Energy rule would result in a 0.7% reduction in carbon emissions. Some facilities, including coal-fired power plants, would result in a net increase in carbon and other pollutant emissions. (Photo: Cathy, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb, in for Steve Curwood.

The Trump Administration EPA recently finalized the Affordable Clean Energy rule. The new rule would replace the Clean Power Plan, put in place under President Obama, with the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The Clean Power Plan never actually went into effect and is still stalled in the courts. Likewise, the Affordable Clean Energy rule is expected to be challenged in the courts by a number of states and environmental groups. The EPA’s own analysis found the rule would result in up to 1400 additional deaths each year from air pollution. And the ACE rule would do little to actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Here to explain is Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau. Pat, welcome back to Living on Earth!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, good to be here.

BASCOMB: So, first of all, Pat, what's the key difference between the Clean Power Plan and the Affordable Clean Energy Rule in terms of how they would each limit carbon pollution?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, well, it's a night and day comparison, because the Clean Power Plan was targeted to reduce carbon emissions by 35% by 2030. This replacement rule that they call the Clean Energy rule would, at best, reduce carbon emissions by 0.7%, which is negligible. And in fact, there are some studies that show that because some of the plants that will be allowed to continue running, these are coal-fired power plants, of course, they could actually result in a net increase in carbon emissions as well as other pollutants.

BASCOMB: So, it's really not doing anything then in terms of reducing our emissions problem.

PARENTEAU: No, it isn't. And ironically, the statute, the Clean Air Act, upon which these rules are based, requires the use of the best system of emission reduction when it comes to carbon pollution and other pollutants, like fine particulates, smog, sulfur dioxide, and so forth. You can get arguments about how broadly to interpret that term; the Clean Power Plan interpreted "system" to mean, the grid system that powers our electricity in the country -- this case, and this rule is just about electricity generation. The Trump administration has taken the narrowest possible interpretation in saying we're only going to look at individual facilities, whereas the Clean Power Plan took the approach, why don't we look at the grid system that's integrated as a whole, and look at different options for dispatching cleaner sources of energy when they're available -- solar, wind, gas -- and not relying so heavily on coal-fired power plants. But of course, that runs squarely against President Trump's campaign promise that he was going to do everything he could to restore coal-mining jobs, and to keep coal-fired power plants operating indefinitely. So this proposed energy rule of the Trump administration is almost the worst emission reduction plan. And it's a very expensive plan, that won't do very much at all.

BASCOMB: Well, what are the costs of the Trump administration's proposal as compared to the Clean Power Plan?

PARENTEAU: Well, the Clean Power Plan did a very comprehensive economic analysis of all the different benefits of converting from dirty fossil fuel plants, particularly coal plants, to these cleaner, alternative sources such as solar and wind and more efficient natural gas projects. Those benefits, net benefits would have been in the billions of dollars, according to the EPA analysis that was done for the Clean Power Plan. This new rule actually will result in a net loss of several hundred million dollars actually a year. This new rule really doesn't require reductions, it gives the states kind of a menu of things they could do to improve the efficiency of how individual coal plants operate. But it really doesn't even mandate emission reductions at all, it really leaves it up to the states to decide, and a lot of these techniques for improving what they call the heat rate efficiency of these plants, they're very expensive. So if you're not significantly reducing pollution, but you are requiring the use of these expensive technologies, you end up actually costing the American economy money, instead of saving money, which is what the Clean Power Plan at least argued that it was going to be doing.

EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler signed the ACE rule in June, but it is likely to get challenged in the courts. (Photo: @EPA on Twitter)

BASCOMB: Can you remind us please, Pat, why is the EPA required to regulate carbon pollution in the first place?

PARENTEAU: Right, so the Supreme Court in the famous Massachusetts vs. EPA case back in 2007, said if EPA makes a, what's called an endangerment finding, if EPA finds that carbon pollution and other greenhouse gases threaten public health and security, then it must take actions to reduce those emissions, which of course would make sense, wouldn't it? And so the Supreme Court has said now, three times in three different cases, EPA has a duty to regulate these emissions, both from power plants and many other sources, industrial sources, and of course, motor vehicles. So that's going to be the legal question in court is, can you literally adopt a rule that will do almost nothing to reduce these emissions in the face of a statute that says you must take meaningful action?

BASCOMB: So the Clean Power Plant is currently tied up in the courts, and it looks like the Affordable Clean Energy rule is heading down the same road. What does that mean, in the meantime?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, a lot of people have thought the Clean Power Plan was dead, and it's actually maybe comatose, but it's not dead. It's been held, put on hold, as a result of the Supreme Court's decision to put the litigation on hold until this new rule from the Trump administration has had a chance to be published. Now that the rule has been published, the DC Circuit Court of Appeals, which is the one court that reviews these kinds of rules, is going to have to compare the two plans, and compare the two interpretations, from the Obama administration's interpretation with the Clean Power Plan, Trump administration with the Clean Energy rule. And the DC circuit is going to have to decide in the first instance, which interpretation is more consistent with congressional intent, and with the language of the statute. And then from there, of course, there will be an attempt to get the Supreme Court to weigh in. And I think the Supreme Court probably will eventually weigh in on this, because it's a very major rule. It has important implications for the economy, for public health, and certainly for dealing with climate change. So, we could still see an outcome in this case, that validated the approach taken by the Clean Power Plan, which would be not what the Trump administration is after, of course. Their primary goal, I think, in promulgating this new rule is to get the courts to decide once and for all, that the Clean Power Plan approach is illegal. That's of course what the Trump administration has been saying about it. They may be surprised by the court saying that it's not illegal. The courts may say it needs to be revised or reviewed in certain ways. But the outcome could certainly be that the core of the Clean Power Plan could be upheld, even by this conservative Supreme Court. So we'll have to wait and see if that's the way it plays out, but it could.

BASCOMB: Mmhmm. Does it seem unusual to you that the Supreme Court decided 10 years ago that carbon emissions had to be seriously addressed from the endangerment finding, and yet we're still trying to figure out how to actually implement it?

PARENTEAU: Well, sure. And I guess the even more striking irony is that the marketplace has already decided to shift to cleaner sources of energy. Solar and wind are the fastest-growing energy sources not only in the country, but in the world. Coal has been reduced to a fraction of its former importance in our energy mix. Natural gas, of course, has come on very strong. So these legal questions about how far the rule should go to limit these emissions is being eclipsed, really, by the marketplace, which is saying, we can find more reliable, more affordable, cleaner sources of energy than coal, and even oil and gas. And that's where the future lies. And so the law is actually trying to catch up with where the market is driving energy systems across the world.

BASCOMB: Pat Parenteau is a Professor with the Vermont Law School. Thanks so much, Pat.

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Bobby. Good to be with you.

Related links:

- Environmental Protection Agency | “Affordable Clean Energy Rule”

- The Hill | “Misguided Affordable Clean Energy Rule Is on the Wrong Side of History”

[MUSIC: Time For Three, “Happy Day”]

Beyond the Headlines

To avoid a vote on climate change legislation, the Republican members of the Oregon State Senate walked out on a session, making it impossible for the legislators to reach a quorum on any issue. (Photo: Jasperdo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: We'll start with the state of Oregon, where there's been kind of a bizarre political play unfolding over the past couple weeks. Oregon State Senate is dominated by Democrats. Republicans hold only 12 of the 30 seats. And in order to prevent any vote on a climate change cap and trade bill, Oregon's Republican senators have apparently literally left the state. They can't stop the bill from passing, but what they can do, is they can stop the Senate from having a quorum to vote on anything.

BASCOMB: Mmhmm. And I understand that this actually had the potential to turn violent.

DYKSTRA: There were suggestions that it could turn violent. One Republican state senator invoked the possibility of having armed militia protect the Republican senators who have gone into hiding. And that's a twist. This is actually not a new political tactic. In places like Wisconsin, where the Democrats were in the minority two years ago, the Dems left the state to prevent a vote on a very strong anti-union bill.

BASCOMB: And of course, Oregon is no stranger to armed militias. There was the incident back in 2016, of a militia taking over the National Wildlife Refuge there.

DYKSTRA: Right. And that ended up with actually one fatality, one of the militia was killed in a car accident. Fortunately, the violence didn't get out of hand, wasn't any worse than that. It's still a kind of a scary situation.

BASCOMB: And so what's the latest with the Republicans?

DYKSTRA: The President of the Oregon State Senate has said they don't have enough votes, even with most of Democrats to pass the climate change legislation, so they've essentially caved. And in this case, the tactic of leaving the state, with the specter of armed militia getting involved, has apparently worked.

BASCOMB: Alright, well, we'll see what happens there, then. What else do you have for us this week?

Over 1.4 billion people rely on water from rivers of the Himalayan Mountain Range, including those in the Hushe River Valley. (Photo: Zerega, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: A little bit about spy satellites. There are various Cold War things that have come into play in a very improbable way to measure climate change. There are spy satellites that have monitored ice and snow levels in the Himalayas over decades to see how the ice and snow melt may be affecting water supplies for a big part of Asia. About a billion people depend on Himalayas ice and snow melt for their water.

BASCOMB: Well, why was the US government interested in that sort of information to begin with?

DYKSTRA: Well, intelligence agencies have long acknowledged that aspects of climate change are huge global security issues, and a billion people without water certainly qualifies as a security issue.

BASCOMB: Well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: Go back to 1978, early July, the town of Soldiers Grove in southwestern Wisconsin is wiped out by flooding of the Kickapoo River. It's at least the third time that downtown Soldiers Grove has been underwater and seriously damaged or destroyed. The town had already decided to relocate itself, but they had trouble getting money from the federal government. After the 1978 disaster, the feds came through. Soldiers Grove, moved itself uphill. The move was a success. Downtown would have been wiped out at least twice more since then by other floods. But the former downtown area is now a park, not a huge disaster if it floods, and downtown Soldiers Grove is safe.

The Kickapoo River flooded several times throughout 2007 and 2008, but due to the decades-past Soldiers Grove relocation, the town’s financial center was spared from the majority of the damage. (Photo: Ryan Rowley, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: So maybe lessons learned for other coastal towns that will be dealing with flooding and sea level rise in the future?

DYKSTRA: Right. There's been one successful effort, had nothing to do with climate change. But in 1964, the town of Valdez, Alaska, the famous oil port, was moved six miles away and uphill. The town of Valdez sprawled along the ocean port. It was destroyed by an earthquake-driven tsunami on Good Friday, 1964. The new town is safe from tsunamis and presumably sea level rise as well. Sea level rise, of course, caused in part by all that oil.

BASCOMB: All right. Well, thank you. Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again soon, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on the stories on our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Oregon Live | “With Four Days Left in Oregon’s Legislative Session, Will Senate Republicans Return Today? Unlikely”

- Oregon Public Broadcasting | “An Occupation In Eastern Oregon”

- CarbonBrief | “Cold-War Spy Photos Reveal ‘Doubling’ of Glacier Ice Loss in Himalayas”

- Read more about Soldiers Grove and their history with floods

[MUSIC: Tony Trishka, “Flying Leaf Jig”]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The world’s corals are in dramatic decline but there is still hope. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at SailorsForTheSea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Time For Three, “Happy Day”]

Resilient Corals Get a Helping Hand

A diver with Raising Coral Costa Rica tends to a floating garden of Pocillopora corals. (Photo: © David Garcia / Ecodiverscr.com)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The world’s coral reefs are in dire straits. More than 50 percent of corals around the world have died in the last few decades and scientists predict that we’re well on our way to a 90 percent die off this century. Warmer ocean temperatures, ocean acidification, and poor water quality combine to make a toxic environment for most corals. But some corals are actually thriving despite their challenges. And scientists like Joanie Kleypas are hoping they will be able to propagate these resilient corals to give struggling reefs a leg up. Joanie is a Senior Scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and founder of the nonprofit Raising Coral Costa Rica. She says their results so far have been encouraging.

KLEYPAS: It's remarkable, really. I mean, you take these small samples of coral, and you put them in the nursery. And, you know, the point I like to make is they really want to grow. Some of these corals look bad when you collect them, and then you put them in this really nice environment and they grow like crazy. It's really a fulfilling experience to see that. In fact, one of the species we're working with, this is off of the Pacific side of Costa Rica, which is really a low diversity area, but the reefs are still really important there. We could not find a species of coral that was very important, it was a branching species; it had been wiped out mainly by sedimentation. But we eventually did find a few colonies, about 10 so far. And we take samples of those, and we put them in the nursery. And they, we just started with little, you know, fingertip-size pieces that were white and bleached. And now we have hundreds of colonies just in the nursery, and we're out planting them back on the reef. And it looks like we might be able to bring that species back. But the entire time we're thinking, well, these corals have all only been found in deeper, cooler waters, we're not sure if they'll survive the next bleaching event. And we recently found a colony in a very shallow, warm water part of the region where we're working. So we know that species survived the last bleaching event. And it would be very good stock, and increase our genetic diversity, to culture that thing, so we, we have samples of that in our nursery right now. And they're growing really well.

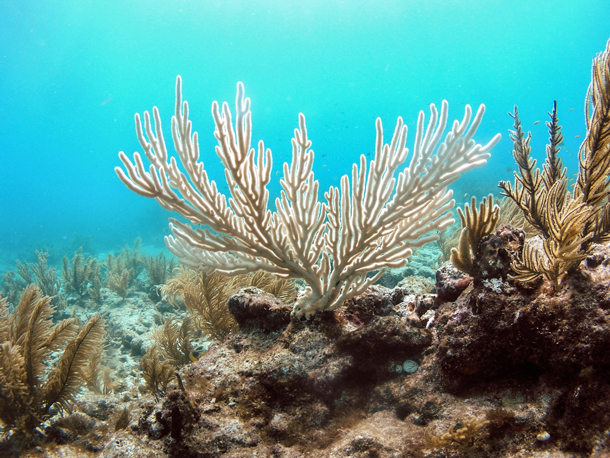

Ocean warming and acidification are causing corals to bleach, meaning that they lose their symbiotic algae. If stressed for too long, they can die altogether. (Photo: Kelsey Roberts, U.S. Geological Survey)

BASCOMB: Mmhmm. So you are taking samples from places that are doing well right now and growing those out, and then planting them out again?

KLEYPAS: Exactly, we're just speeding up what they would do naturally, by probably about five times or more. When you knock a population of corals down to so few, then when they do reproduce and release their eggs and sperm in the water column, the probability of an egg and a sperm finding each other is really low. But if we can go into some of these areas and plant thousands of these corals of different genotypes, when they spawn, then they will find each other. So, that sort of brings them past this threshold of having such low numbers to a point where they can become self-sustaining again.

Pavona corals transplanted by Raising Coral Costa Rica. Pavona corals are nicknamed cactus, potato chip, and lettuce corals. (Photo: Raising Coral Costa Rica)

BASCOMB: Right. And are you just working in Costa Rica, or do you have plans to collect corals in other parts of the oceans?

KLEYPAS: So far, we're really concentrating on the Pacific side of Costa Rica. There is a lot of work being done all over the Atlantic, people are doing this a lot with a couple of the endangered species, in particular, of the staghorn and elkhorn corals. These are big, major species that used to be the foundation of the reefs there. And they've had a lot of success of bringing these corals back and increasing the genetic diversity that they have in their nurseries, and in starting to work with the other species as well, so there's been a lot of success in the Caribbean. On the Pacific side of Costa Rica, there's very few people looking at this. And we like working there because even though there's just a few species, they're really tough there. They're tough because they have to be; it's kind of a harsh environment. The temperatures, you know, can be quite extreme, the pH of the water is pretty low, and yet they thrive. And if you're going to propagate species for the future, you need to find those tough corals.

BASCOMB: So can they only live in that one environment? Or could there be a scenario where you take those corals in the Pacific of Costa Rica, and plant them in the South Pacific, you know, someplace else entirely, where maybe you're not finding those tough, resilient corals? Or would they not survive because they just don't belong there?

Pocillopora corals like these transplants are also known as cauliflower corals. (Photo: Raising Coral Costa Rica)

KLEYPAS: This is one of the other interventions that scientists are talking about: can we move corals around? It's one of the riskier ones. The problem is when you move corals around you, you move around not just the coral, you move around the bacteria that it has on it, you move around all these other species that live on the coral. So there's a risk of introducing invasive species or diseases, so you have to be really careful about moving them around. And certainly, we don't recommend anyone put their own corals from their aquarium in the ocean, just for that reason, we want to avoid any kind of invasive species. But there are also ways to get around that. So they're starting to freeze eggs and sperm. And recently, there was a project where they were able to fertilize eggs of a coral with sperm that were transported from the other side of the world and produce viable offspring. So, that eliminated the bringing of invasive species with that, if you're just bringing the sperm, that eliminates that probability. So there's some really cool and innovative ways that people are figuring out how to deal with these risks.

BASCOMB: To what extent are people talking about genetically modifying corals at this point, in another effort to save them?

KLEYPAS: Well, when you say genetic modification, you can think of it two ways. One is, is sort of the natural way, by like, crossbreeding corals. Again, it's the same sort of thing we do with crops and so forth, you just breed a better coral. There are some people thinking about creating better corals through genetic modifications, through some of these new genetic techniques. And they're thinking about doing that not just with the coral animal, but with the symbiotic algae that lives inside the coral and makes it such an efficient organism. That scares a lot of people. I think, you know, we need to be careful on that, I don't think we're going to be in danger of creating Frankenstein corals. But most of the genetic studies that are going on now are really designed to understand what's going on inside the coral when it is adapting to a temperature change. How do we understand what's happening to that coral by looking at its genetics, rather than trying to change the coral with the genetics. But it is something in the toolbox that needs to be evaluated along with the risk before we use that kind of technique.

BASCOMB: How have corals responded to previous fluctuations in global temperatures? You know, the Ice Age and things like that. I mean, is this the first mass dying of corals that we've seen, you know, in their history on earth?

Joanie Kleypas is a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder CO, and studies how climate change and ocean acidification impact coral reefs. She has conducted research on coral reefs for more than 30 years, and now concentrates on finding solutions to coral reef decline. (Photo: Carlye Calvin, © UCAR)

KLEYPAS: Well, corals -- you know, the stony corals, those evolved in the Triassic, that was 240 million years ago. They're still around, and they've had their ups and downs through geologic history. They've apparently, you know, almost completely disappeared from the geologic record. There's no sign of them ever being preserved. But they always seem to come back. The last time they had a big wipeout of the corals was when the dinosaurs went extinct. And then again, 10 million years after that, in a period of time when the Earth's atmospheric carbon dioxide also went up really quickly. And the reefs that had finally started growing again after the Cretaceous event, they ended up really diminishing a lot during this high CO2, high ocean acidification event 55 million years ago. So they've gone through all of these cycles, up and down, up and down. But most of those changes have been a lot slower than what we're seeing today. That's the problem. We know corals can adapt. They have a huge capacity for adaptation. But right now, it's just too fast. It's faster than they can do it themselves. We are having to become part of that ecosystem to help speed up the rate at which they can adapt.

BASCOMB: Joanie Kleypas is a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and founder of the nonprofit Raising Coral Costa Rica. Joanie, thank you so much for sharing your story with me.

KLEYPAS: Bobby, thank you. It's been a pleasure and a privilege. Thanks.

Related link:

About Raising Coral Costa Rica

[MUSIC: Bill Monroe, “The Sailor’s Hornpipe”]

Repairing Puerto Rico’s Corals

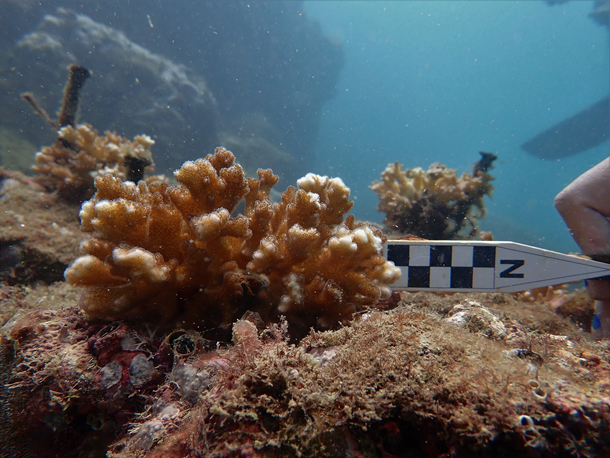

Grupo Vidas workers have used zip ties to reattach hundreds of coral fragments to the reef near Vega Baja. (Photo: Ricardo Loreano)

BASCOMB: Given the right environmental conditions, corals can be surprisingly easy to propagate and re-attach to an existing reef. When Hurricane Maria pummeled Puerto Rico in 2017, roughly 10 percent of the island’s corals were damaged; large chunks were broken off by rough seas and ocean swells. But in this story that first aired shortly after the hurricane, I found there’s still hope for thousands of battered bits of coral lying around the sea floor.

[WAVE SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: I’m standing on a tall dune near Vega Baja on Puerto Rico’s north coast. The ocean stretches out in shades of dark blue, turquoise, and pale aquamarine.

But interspersed among the usual colors of a tropical ocean are patches of brownish orange – elkhorn coral. Salvador Loreano is a worker with the environmental NGO Grupo V.I.D.A.S. Their main task is coral restoration.

S. LOREANO: Our goal right now is to plant coral fragments here because you know that Maria, Hurricane Maria, came here and devastated the island. This caused great damage to the coral reef because the first time we went to there after Maria, the reef was like destroyed, like we’d see big coral colonies upside down and a lot of dead coral.

BASCOMB: As long as they remain submerged under water, these coral, which are colonies of tiny invertebrate animals, have a 20 percent chance of survival. But that increases to more than 90 percent if they are attached to a larger structure, not getting banged around by the surf or smothered with sand.

The Grupo Vidas crew taking a break from their coral restoration work. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

If a piece of coral is at least 2 inches long and 80 percent healthy, it can actually be reattached to an existing reef. Salvador points towards the water…

S. LOREANO: Over there is my sister and that’s one of my friends that work here. They’re preparing to enter to the Arrecife El Eco.

BASCOMB: Can we go see what they’re doing?

S. LOREANO: Yes.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Mariola Loreano is standing on the shore in about a foot of water.

S. LOREANO: Mariola!

BASCOMB: She’s wearing a rash guard to protect from the hot tropical sun.

A mask is perched on her forehead, a snorkel dangling off it. She’s holding a white milk crate with all the tools the crew will need for their morning’s work.

M. LOREANO: Yeah, basically what we have in there is a sledge hammer; a slate where we write our tallies, basically, which is all of the fragments that we’ve successfully planted; a bag for any trash that we find inside the ocean; a buoy so it floats.

The beach near Vega Baja, Puerto Rico. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: So, should I put on my fins then and we head in?

S. LOREANO: if you’re using flippers, I recommend that you either walk sideways or back because, you know, if you use flippers walking front, it’s going to be rather difficult.

BASCOMB: I’m going to fall on my face.

S. LOREANO: Most… mostly. [LAUGHS] I can help you enter the reef, because, well, it’s all rocky, but there are a lot of sea urchins there.

BASCOMB: Oh, so it’s spiny.

S. LOREANO: Yeah, but it’s not that big of a deal because they’re really deep inside the crevices so they won’t sting you.

BASCOMB: So, is there any other advice I need before we go in?

S. LOREANO: One thing you got to be careful of, it’s not that big of an issue, but scorpion fish have also appeared here. You know how they camouflage very well?

BASCOMB: I don’t actually.

S. LOREANO: They rely on their camouflage. And sometimes their camouflage is really good. [LAUGHS] So it’s best to keep an eye out where you put your hand and everything.

BASCOMB: I’m not going to touch anything.

S. LOREANO: I know, I know! – just in case.

[SOUNDS OF WATER SPLASHING]

BASCOMB: We put on our mask, snorkel, and fins and walk backwards into the bath-warm water, stepping over the sharp black sea urchins.

[SPLASHING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Once the water is knee-deep, we splash in and swim about 500 feet to the reef.

[UNDERWATER BREATHING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: A rainbow of fish greets us – green fish with florescent blue heads, black fish with yellow stripes, green fish with pink stripes. They’re all juvenile fish, and the reef is a critical habitat for them. Bulbous brain coral dot the sea floor, and orange elkhorn coral stick out at awkward angles, much like its namesake.

[SCRAPING SOUND]

BASCOMB: A worker named Ernesto is already hard at work.

Ernesto Vélez Gandía stands on the beach getting ready to reattach bits of coral broken off the reef by Hurricane Maria. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

He uses a wire brush to scrape algae off a piece of coral the size of a ping pong paddle and does the same to a suitable spot on the reef. Just like gluing two objects together, you need to start with a clean surface on both sides. Then he pulls a plastic zip tie out of his sleeve and uses it to attach the coral in place.

He uses pliers with a florescent pink handle to pull the zip tie tight and cut off the excess plastic, which he sticks into his other sleeve. This piece of coral is now one of hundreds just like it pinned to the reef with zip ties. And in two to three weeks, it will grow onto the reef enough to stay put on its own.

[WAVE SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Roughly 15 percent of the coral here at Vega Baja was broken off by hurricane Maria. But these corals evolved with hurricanes. If hurricane damage was the only issue, this work wouldn’t be necessary. But much like the world’s coral reefs in general, this reef has a lot of challenges.

Grupo V.I.D.A.S. worker Ernesto says one of the biggest problems is algae blooms from sewage runoff. In many places the coral is essentially smothered, leaving it a ghostly gray color.

VÉLEZ GANDÍA: Yeah, those… they look like zombies, right there.

BASCOMB: They look like zombies, like Day of the Dead.

VÉLEZ GANDÍA: Yeah, it’s like Day of the Dead but under the water.

BASCOMB: There is a very large dead coral at the entrance to the reef in the shallowest, warmest water. Ernesto believes that one died not from algae blooms but from stress of a warming ocean.

A piece of dead brain coral washed up on the beach.(Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

VÉLEZ GANDÍA: The water is getting warmer. Every year it’s getting warmer.

BASCOMB: Standing on the dune in a light blue rash guard and smoking a cigarette, Ernesto talks about the death of that coral as one might talk about a member of the family passing away.

VÉLEZ GANDÍA: And we got a lot of love for him. We saw him alive, very alive. He is one of the oldest in our reef. But he start dying, we saw the process of his death. So, we just admire him and remember him. It’s very sentimental, I don’t know, but it’s deep in the heart.

BASCOMB: Adding to the warming water and algae blooms, ship groundings break off large chunks of coral each year; collectors intentionally break it off to sell for home aquariums; and spear fishermen damage it with their equipment.

Ocean acidification and coral bleaching are also huge problems for the world’s corals, and Puerto Rico is no exception. The team admits it’s an uphill battle to save this reef, but Salvador says they’re already seeing results.

Elk horn coral are part of a vital reef ecosystem that provide habitat for fish. (Photo: Sean Nash, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

S. LOREANO: Our work has given us results like species that we thought we’d never see again started to return, like moray eels, scorpion fish, sea cucumbers, puffer fish, sand dollars, which are a species of flat sea urchin, and also there’s like a spotted eagle ray hanging around over there.

BASCOMB: Projects like this have actually been going on for nearly 20 years on a small scale. But one million dollars of post-Maria funding allowed scientists from NOAA, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and independent NGOs to speed up their efforts. Workers have been able reattach roughly 15,000 pieces of coral to the reefs surrounding Puerto Rico.

Related links:

- Grupo Vidas

- NOAA page on Corals

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: The Auklet’s Whiskers -- Not Just for Show

Whiskered Auklets use their whisker-like feathers to help sense their surroundings while nesting in their dark, cliff-side nest cavities. (Photo: © Sergey Frolov)

BASCOMB: The whiskers on a cat help our feline friends navigate in the dark. But it turns out, some birds have their own kind of “whiskers” too. BirdNote’s Michael Stein tells us more.

BirdNote®

The Auklet's Whiskers - Not Just for Show

[Ocean waves and wind]

STEIN: At dusk, in the far western reaches of Alaska’s Aleutian chain of islands, thousands of tiny Whiskered Auklets fly in to nest in cavities deep in rock crevices. [Whiskered Auklet calls, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/133048, 0.11-.13, repeated] Whiskered Auklets are miniature relatives of puffins and murres. Charcoal gray, they're about eight inches long and owe their name to the long, slender white plumes that sprout from their heads each summer. Two rows down the side of the face and a third set that stands like antennae above their eyes. These fancy white plumes very likely play a visual role in courtship and mate selection. But they're not just for show.

Whiskered Auklets are close relatives of puffins and murres (Photo: Toshiji Fukuda CC)

[Whiskered Auklet calls, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/133048, 0.11-.13, repeated]

The auklets’ “whiskers” have an important sensory function, too. When the birds enter their cliff-side nest cavities, they find themselves in utter darkness. The “whiskers” enable the auklets to feel their way along in the dark. Much like the whiskers of a cat, they're acutely sensitive.

[Whiskered Auklet calls, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/133048]

By summer’s end, when nesting is done, Whiskered Auklets return to life on the open sea, like many seabirds. And with no dark crevices to navigate and no mates to impress, they molt their multi-purpose whiskers.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Whiskered Auklet [133048 ] recorded by S S Seneviratne. Ambient sounds: Nature Sound 02 'Wind Mod Soft'; NatureSound 23 'Surf Mod Sandy' recorded by Gordom Hempton of Quiet Planet.com

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org June 2017/2019 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# WHAU-01-2015-06-29 WHAU-01

Sources: Tim Birkhead’s Bird Sense;

http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/species/factsheet/22694918; http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/076/articles/breeding

https://www.birdnote.org/show/henry-david-thoreau-and-wood-thrush

BASCOMB: For pictures of the Auklet’s whiskers, navigate over to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Find out more about this story on the BirdNote website

- Learn more about the Whiskered Auklet

[MUSIC: Chick Corea & Gary Burton, “No Mystery” on Native Sense, by Chick Corea, Stretch Records]

BASCOMB: Just ahead on Living on Earth – The California Condor, once on the brink of extinction is making a big comeback. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United

Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions

designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC

companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are

helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by

tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI,

Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Chick Corea & Gary Burton, “No Mystery” on Native Sense, by Chick Corea, Stretch Records]

Freshwater Under the Sea

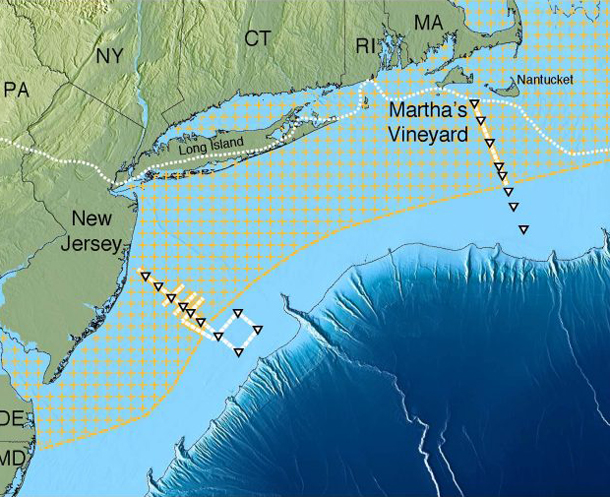

Using electromagnetic waves, scientists at Columbia University identified a band of freshwater-containing underground sediments that spans from the coast of Massachusetts to New York, and juts out as far as 75 miles into the Atlantic. (Photo: Courtesy of State of the Planet)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Just ahead, helping pollinators one yard at a time but first this note on emerging science from Joseph Winters.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

WINTERS: Some of the world’s biggest sources of freshwater don’t rain from the sky or melt from a mountaintop, but come from beneath our very feet. Underground aquifers like the Ogallala of the US Central Plains—one of the biggest aquifers on Earth—are a vital source of fresh water.

Now, it turns out one of the largest known underground aquifers is actually under the ocean. A team of researchers used electromagnetic waves to detect an enormous cache of freshwater trapped in underground sediments off the coast of New England. Their data suggests the freshwater sediments span from the shores of Massachusetts to New York and jut out as far as 75 miles into the Atlantic. Their study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, estimates the aquifer could hold as much as 670 million cubic miles of freshwater. That’s one and a half Lake Ontarios.

To find freshwater beneath the ocean, the researchers placed electromagnetic receivers on the ocean floor. The devices measured the strength of underground shockwaves, which scientists emitted using a device they dragged behind their ship. Since electromagnetic waves travel better through saltwater than through freshwater, their data revealed thick bands of “low conductance,” places where the electromagnetic waves seemed to travel poorly, indicating a deep layer of freshwater sediments.

The freshwater aquifer identified in the study spans the entire New England coast and into New York, and is suspected to hold 670 cubic miles of water—that’s as much as one and a half Lake Ontarios. (Photo: Carol M. Highsmith, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Most of these bands began 600 feet below the seafloor and reached down as far as 1200 feet.

Water from this particular aquifer would probably need to be desalinated if it were to be used for drinking water or agriculture. And it’s unlikely that states in the Northeast would choose such a costly option, but researchers are hopeful that their methods will lead to the discovery of more offshore aquifers in other, drier parts of the world. For places like southern California or Saharan Africa, a seaside aquifer could be a desperately-needed resource for when all other options dry up.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Joseph Winters.

Related links:

- State of the Planet | “Scientists Map Huge Undersea Fresh-Water Aquifer Off U.S. Northeast”

- State of the Planet | “Cape Town Water Crisis Highlights a Worldwide Problem”

- Read the researchers' article here

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Turning Backyards Into Pollinator Havens

Clover is a great plant to have mixed in with your lawn for pollinators. (Photo: Flickr, Martin LaBar CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: Recent studies find insect populations are in sharp decline. As many as 40% of insects may be facing extinction in the coming decades. That includes critical pollinator species like bees, which are responsible for pollinating the crops that provide one in three bites of food we eat. Cities and towns around the world are beginning to take the problem seriously. In London, they’ve planted a 7-mile bee corridor to provide wild flowers for the city’s pollinators. And closer to home, lawmakers in Minnesota have approved a new program that pays homeowners to convert their lawns to pollinator-friendly habitat. With us to talk more about the Minnesota program and what people can do to help pollinators is Sarah Foltz Jordan, a Senior Pollinator Conservation Specialist with the Xerces Society. Thanks for joining us, Sarah!

The state of Minnesota has launched a new program to help support the Rusty Patched Bumblebee, along with other native pollinators. (Photo: Courtesy of Xerces Society/ Clay Bolt)

FOLTZ JORDAN: Thank you!

BASCOMB: So, how will this new program in Minnesota work? Can you break it down for us, please?

FOLTZ JORDAN: So, the idea is that the program will provide funding to residential sites where turf conversion is a possibility. So, the idea is we'll be converting lawn or turf, managed turf, to something that's much more beneficial for pollinators. And there's a variety of options there, ranging from something simple like introducing clovers and other legumes into grasses. But, also, my expectation is that the majority of the funding will go towards converting that turf to diverse native plantings for pollinators that provide blooms spring through fall and really do a good job of supporting a wide variety of the species.

BASCOMB: And, how much money is being put into this program? How much can homeowners expect to be compensated?

FOLTZ JORDAN: The amount of money that was allocated for the program is $900,000, to be spent down over a two-year period. I am not sure what individual landowners can expect to receive. It will be, you know, really dependent on what projects they choose to do and at what scale.

Butterflies, like this Red Admiral, are important pollinators, too! (Photo: Courtesy of Xerces Society/ Sarah Foltz Jordan)

BASCOMB: But they'll get reimbursed up to about 75% of their costs for doing this, is that right?

FOLTZ JORDAN: Exactly! Yeah. And even higher than that if they are in a priority zone for the Rusty Patch Bumblebee, which was a species that the program is kind of designed to really help support.

BASCOMB: So, why the Rusty Patch Bumblebee? Why design this program around that particular insect?

FOLTZ JORDAN: In 2017, it was listed as federally endangered. It has now declined by about 87%, it's still hanging on. In the metro region of Minnesota and Madison, Wisconsin, there's a few strongholds, although they could certainly be stronger. What we're looking at here is trying to boost up the population of this bee by connecting different places where we know it's still occurs, providing some connectivity by increasing habitat in those corridors. And, also just bringing up the number of flowers across its range.

BASCOMB: And presumably planting flowers and native plants and things will help a whole lot of pollinators other than just the Rusty Patch Bumblebee.

FOLTZ JORDAN: Exactly. Yup, it's sort of a flagship species. But these plantings will benefit a lot more than that bee. And I'm expecting many people will be really interested in supporting the monarch butterfly with their plantings as well by including milkweed host plants and a wide variety of nectar plants.

BASCOMB: Right. Can you put this into a larger context for us? I mean, what's the current situation with bees and pollinators more generally.

FOLTZ JORDAN: So, the Rusty Patch Bumblebee, which I was talking about earlier, has declined by 92%. So, that's pretty dramatic. It was formerly very common, and is now barely hanging on. Monarchs, similarly, are, you know, one of our more charismatic, well-studied insects. So we've seen 60 to 90%, declines in population size, depending on what years you're comparing, in our Eastern population. I mean that's sort of the tip of the iceberg. There's a lot of species that are not as well on our radar. And it's really hard to say how they're doing.

BASCOMB: The monarchs, as you said, are a charismatic insect, you know, maybe people had them in jars in school when they were kids and things. But, pollinators by definition are extremely important, for ourselves and for the ecosystem as a whole. Can you talk about that a bit, please?

Having educational signage in your yard about pollinator habitat is a great way to inspire others to create pollinator habitat in their yards, too. (Photo: Courtesy of Xerces Society/ Sarah Foltz Jordan)

FOLTZ JORDAN: Sure! Yeah. I mean, the economic significance gets a lot of attention. So, you know, our food systems are really dependent on pollinators. But, I don't think we give pollinators maybe as much credit as we should for their role in preserving and sustaining our natural ecosystems. So, about 85% of our wild flowering plants are pollinator dependent. And, you know, pollinators are also kind of keystone species in other ways. So, they're providing pollination services that enables the fruit and seedset of a lot of plants, but they also are being consumed by birds and small mammals and kind of supporting these diverse food chains and ecosystems in that way as well.

BASCOMB: Hmm. And, so why are insects and pollinators in such sharp decline right now?

FOLTZ JORDAN: It's really a multi faceted problem. So, you know, they're being hit in a number of ways. There's been dramatic habitat loss, increases in pesticides, including a lot of pollinator lethal pesticides, and also increased disease spread. So, kind of circling back to the program we were initially talking about, this is addressing just kind of one aspect of pollinator threats, that habitat piece, but it's something that we all have the power to do something about. So, as we think about increasing habitat for pollinators in our yards and bringing in more flowers, my hope is that we're also thinking about pesticide reductions.

Pruning raspberry canes provides nesting habitat for many important bee species. (Photo: Courtesy of Xerces Society/ Sarah Foltz Jordan)

BASCOMB: So, Sara, what can you suggest for someone that's listening now and maybe wants to make their own yard more pollinator friendly?

FOLTZ JORDAN: The most important thing we all can start doing is thinking about our landscaping decisions, not just in terms of our own aesthetics, and, you know, maybe the status quo. But also thinking about these decisions in terms of how these plants that we choose to put into our yards can in turn support higher trophic levels, so the ecosystem a little bit more broadly. And I think when we start thinking through that lens, it becomes really clear that native plants are essential. And when I think about native plants, butterflies and moths really kind of hit home for me, because many of these butterflies and moths have really, really close relationships with certain native species that they can only feed on. And then a lot of our bees also are specialist species, and will only select pollen to feed their babies from certain plants. I think it's a little bit confusing for people sometimes because butterflies and bees will visit non-native plants. So it can look like 'Oh, these plants are doing a great job at attracting bees and butterflies.' But just because they're visiting doesn't mean that the nutrition that they're getting is adequate or preferred. And I noticed this in my own yard, I still grow quite a few cut flowers. But I used to have a lot of cut flowers and non-native ornamentals and have gradually chipped away at that and started converting most of that to native flowering plantings. And it has been just astounding to witness that change in the types of insects that I'm seeing and the abundance of insects that I'm seeing, just because of the plants being better suited to meet their needs.

Many cavity nesting bees will create nests with chambers for their young in dead raspberry canes. (Photo: Courtesy of Xerces Society/ Sarah Foltz Jordan)

BASCOMB: And, clover even seems like a good place to start. You can plant that even in with your own grass, and it's relatively short. So it's not, you know, such a big change for people, I would think?

FOLTZ JORDAN: Exactly, yup. That's kind of a baby step, is getting some clover into your grass, or even easier would be just to - a lot of people have flowering weeds in their lawns that they work really hard to keep out. But, again, if we can kind of change our aesthetics and learn to see those weeds as something beneficial for other species that can be really helpful, just kind of letting those things... letting them go.

BASCOMB: So, Sarah, beyond flowers and native grasses and things, is there anything else that people can do?

Sarah Foltz Jordan is a Senior Pollinator Conservation Specialist with the Xerces Society. (Photo: Courtesy of Xerces Society/ Sarah Foltz Jordan)

FOLTZ JORDAN: Yeah, flowers are critical for providing really important food. Like we've been talking about, native is best. But, we also need to remember that these insects have nesting and overwintering needs, basic needs for shelter, I guess. So, we really advocate for people trying to leave things like dead stems left in wildflower gardens, branches, brush piles, leaf litter, rock piles, or rock walls. One of my favorite kinds of bees is the Small Carpenter Bee. They nest in stems. So, I planted raspberry bushes right outside of our front door, and I prune them back every year at about, I don't know, maybe three feet, two to three feet tall. So it's a really easy height for me to observe what they're doing there. And what happens is the raspberries will flower in the spring and the little bees will come out and they'll collect pollen and bring it to their nest. And they nest in these raspberry canes. So, the cut ends that I create is the entrance to their homes. And I can watch them all day, just like, gathering pollen bringing it in. They make little bedrooms within the stem for each of their offspring. So, every baby gets its own room with its own little ball of pollen and nectar and then a wall and then they do it again. And it's kind of this linear series. And, then they actually exhibit parenting behavior as well, which is a little bit unusual in insects where they will watch that nest and protect it from predators and make sure those babies get off to a good start when they finally emerge. So, that's one of my favorite little bees to hang out with. (LAUGHS)

BASCOMB: Sarah Foltz Jordan is a Senior Pollinator Conservation Specialist with Xerces Society. Sarah, thank you so much for all this information.

FOLTZ JORDAN: Yeah, thank you, Bobby! It was my pleasure.

Related links:

- More about the MN pollinator program

- Learn more about what native plants are good for pollinators in your region

- More about the Rusty Patched Bumblebee

[MUSIC: Ron Block, “Summers Lullaby” on Walking Song, Rounder Records]

The Mighty Condor

The California condor, though still endangered, was on the brink of extinction until recently. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

BASCOMB: Just a few short decades ago, the California condor was on the verge of extinction. The Condors ate carcasses with lead bullets in them and were dying en masse from lead poisoning. Then the US Fish and Wildlife Service stepped in. Now, with over 400 in the wild, the condor is making a big comeback. And as Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender reports, when it comes to condors, big is the operative word.

El Condor Pasa

California Condor

Pinnacles National Park

© 2019 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: Condor, bigger than a barndoor, blows on by. Wings outstretched and motionless to the naked eye. Tail feathers spread like fingers, she keeps her trim. Listen to the music of those wings, in wind. Crackling like parchment wrinkled and torn -

Condor! Air borne!

Working the thermals she spirals up and out and around again for a better look. Orderly. Curious. All life to her is an open book. Intelligent. Penurious. Her only wealth derives from that of which all life must part.

Down (the direction where she feeds).

Up (the angle that she flies).

Never hurried, never too late

She only eats when someone dies.

Well-apprised, of all the perils flesh is heir to she reads the Auguries of your Fate:

The head of the California condor is hot to the touch. Their body temperature runs 104 to 105 degrees Fahrenheit. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Lack of a fair shake

Lost in a place where water is the exception

A bad break

Bad directions

The stain of lard on your cardigan and a middle that obfuscates toes and feet (proceeding from a confluence of daytime sleep and midnight eat)

Too much emotional freight

Up too early, home too late

Foreclosure and other forms of modern distress (these are the hands lay heavy on the chest)

A face filled with Anger, with Hate

A fast car (Inadequate brakes)

Gain without Pain

No modulation

Sunstroke

Thin Ice

No vacation.

A Bolt from the Blue

Too Much Red Ink,

Too Much to Drink,

Too Much Action

Not Enough “THINK!”

Here I stand at the edge of this cliff wondering is she wondering how good my footing really is? Light catches her eye in a certain way, her silent reply:

The wingspan of a California candor can reach 10 feet (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

“I know you, I know your thoughts and where they lead. Have no fear. No lasting harm will come to you. Only to that part that has already passed away.”

BASCOMB: That’s Living on Earth Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender.

Related link:

Mark Seth Lender’s website

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Lovers Paradise” on The Dark Before the Dawn, Atlantic Jazz]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Diego Arenas, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joseph Winters, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Our executive producer Steve Curwood will be back next week. Special thanks this week to the US Fish and Wildlife Service Condor Rehabilitation Program. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth