March 8, 2019

Air Date: March 8, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Tornado Clusters and Climate Disruption

View the page for this story

Tornado clusters are becoming more frequent as the planet warms, scientists say. There were about 40 tornadoes on March 3, 2019 in the Southeastern US and the most powerful one tore through Lee County, Alabama and left neighborhoods flattened, 97 people injured and 23 people dead. The other tornadoes that day were less dangerous, but still damaging in some cases. Florida State University Professor James Elsner spoke with host Steve Curwood about how tornado outbreaks are changing in a warming world. (06:30)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood discuss the City of Miami's decision to ban the use of glyphosate by municipal employees. Then, the two take a look at the lengthy legal saga of Donald Trump's fight against a wind farm in the view shed of his Scottish golf resort in Aberdeenshire. Finally, they recount two massive oil spills -- Exxon-Valdez in 1989, and the Taylor spill, which has been going on since 2004. (04:14)

Oceans Losing Oxygen

View the page for this story

Warmer water holds less oxygen than cool water does, so as the globe and the oceans heat up, they’re losing oxygen. The problem is heightened by pollutants like nitrogen and phosphorus, which contribute to oxygen-starved “dead zones” in the Gulf of Mexico and elsewhere. Denise Breitburg is a senior scientist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and explains to LOE’s Bobby Bascomb what declining ocean oxygen is doing to sea creatures, and what needs to be done to address the crisis. (08:40)

Note on Emerging Science: Matchmaking for a Frog Named "Romeo"

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Sehuencas water frogs, like other amphibians, have been devastated by the chytrid fungus, and a frog that scientists named “Romeo” was the last known frog of his kind until scientists discovered a couple of potential mates for Romeo hiding in the Bolivian mountains. As Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports with this note on emerging science, they hope that these frogs may be immune to the deadly chytrid fungus. (01:30)

Cloning Giant Sequoias

View the page for this story

The 3000 year-old Giant Sequoia and Coast Redwood trees of the Pacific Northwest are among the biggest and oldest individual living things on our planet. Sadly, all but a few were cut down for logs decades ago. To help restore these majestic trees which sequester large amounts of carbon, the non-profit organization Archangel Ancient Tree Archive has dedicated its efforts to cloning their DNA. David Milarch, co-founder of Archangel Ancient Tree Archive, tells host Bobby Bascomb why cloning specific trees can help restore a resilient population. (09:56)

In Search of the Canary Tree

View the page for this story

Southeast Alaska’s Nootka cypress also known as the yellow cedar tree, is in trouble. Climate disruption is bringing more erratic weather to the area, and the huge cypresses known as yellow cedar trees are among the first species to suffer. In the book, “In Search of the Canary Tree: The Story of a Scientist, a Cypress, and a Changing World,” author Lauren Oakes describes how Southeast Alaska’s forests and people are responding to the widespread die-offs of the yellow cedar trees. Lauren Oakes joins host Steve Curwood to discuss how resiliency is helping the forest and local human communities adapt to the loss of this culturally and ecologically important species. (15:11)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Denise Breitburg, James Elsner, David Milarch, Lauren Oakes

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Oxygen levels in the world’s oceans are in decline partly because climate change increases water temperatures.

BREITBURG: Warm water can't hold as much oxygen as cool water can, and since the 1970s the open ocean has lost about 2 percent of its total oxygen. That may not sound like a lot but that's 150 billion tons of oxygen.

CURWOOD: Also, some of the best trees on earth for quickly soaking up carbon dioxide are the giant sequoias.

MILARCH: The beauty of redwoods is they almost refuse to die. You can’t burn them down, they withstand fire. Disease hardly ever attacks them. You can dynamite them, you can cut them down, but they’ll cling to life.

CURWOOD: Making clones of redwoods cut down more than a century ago.

That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Tornado Clusters and Climate Disruption

Although the frequency of tornadoes overall has not been increasing with climate change, research led by Florida State University scientists shows the frequency of tornado clusters has increased. (Photo: Unsplash, Nikolas Noonan CC)

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. With our climate changing, not only does our world get warmer, but extreme weather events can become more frequent, from heat waves to major hurricanes, and even clusters of tornadoes! On March 3rd in Lee County, Alabama, a massive tornado flattened neighborhoods and killed 23 people. It was among some 40 other lesser tornadoes that same day. James Elsner of Florida State University has documented how the warming planet appears to promote more tornado clusters. Professor Elsner joins us now from Tallahassee in Leon County Florida which, by the way was hit by one of the smaller tornadoes in the recent cluster.

Welcome to Living on Earth, Professor!

ELSNER: Thank you, Steve. Nice to be here.

CURWOOD: So during that outbreak of tornadoes on March 3rd, they came pretty close to you there in Tallahassee, so I understand it.

ELSNER: That's right. The storm started up in Alabama, and Georgia. And then as the evening progressed, there were some tornadoes here in Leon County, right near Tallahassee.

CURWOOD: So you had a tornado warning, but you didn't hear that rumbling train, I guess?

ELSNER: Not where I am, but the surveyors were out on the fourth, looking at damages in the area of Tallahassee, and they did find evidence of EF2 damage in Leon County, that's the strongest tornado we've seen in this part of the country for at least several decades.

In Lee County, Alabama destruction from the March 3, 2019 tornado left 23 dead and much of the community destroyed. (Photo: Flickr, Red Cross CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So we spoke with you in 2015 about how climate change appears to have an impact on the frequency of tornadoes remind us of that research and what you have found since we last spoke?

ELSNER: Yes? Well, if you look at the numbers of tornado is occurring in the United States over from year to year, it's certainly various, it's about 1200 per year, and it goes up and down, but we don't see any long term trends in the number. What we found a couple years ago was that although there isn't a trend in the overall number of tornadoes, they tend to be coming in bigger bunches. So there are fewer days with tornadoes, but the days that tend to spawn tornadoes tend to produce many of them. And so this recent outbreak in the southeast on Sunday was an example of a fairly large outbreak of close to 40 tornados.

CURWOOD: So you call this a tornado cluster? Why do you think we're seeing more of these clusters of tornadoes in recent years?

ELSNER: Well, I think it has to do with the fact that the atmosphere is less conducive to the formation of tornadoes, largely because of the warming air aloft, and so that tends to inhibit the instability it keeps it in check. But we're also seeing an increase in wind shear on days when the conditions are right for tornadoes, and that increasing shear tends to produce bigger outbreaks.

CURWOOD: In the instance of Lee County, Alabama, the tornado that was so deadly there, was part of this cluster of some 40 tornadoes. I gather that more and more we will see events like this clusters, maybe some smaller tornadoes with maybe a couple of really crunches in the middle?

ELSNER: Yeah, that's right. So these outbreaks tend to produce a distribution, if you will, of tornado intensities within a cluster of 40 tornados there may be one or two violent tornadoes, that's an EF4 or an EF5, and then maybe a half a dozen or so EF3 tornadoes, and then quite a few more EF2 tornadoes. And so this distribution of tornadoes kind of scales with the size of the outbreak, the number of tornadoes, so when we see bigger outbreaks, we can expect to see more violent tornadoes.

CURWOOD: Now, research indicates perhaps the tornadoes are moving east. What's your opinion of such findings?

ELSNER: Well, that was an interesting study last year on this shift in the occurrence rate of tornadoes across the US showing that maybe the South East United States is becoming more of a hotspot for tornado activity. I think its preliminary. It's interesting research, but it's a possibility. One of the things we have to keep in mind is that there isn't a lot of wiggle room where tornadoes can form. That means that the conditions for tornadoes are fairly sensitive, and it's unlikely for that distribution to change considerably in terms of where tornadoes will go – and so in other words, we're not going to see tornadoes west of the Rocky Mountains, we're not going to see many tornadoes in West Virginia. And so I think we're somewhat limited on the spatial movement of tornado patterns.

CURWOOD: Remind us of the most favorable territory for tornadoes.

ELSNER: Anywhere east of the Mississippi is the favorable region of tornadoes, we've come to know the Tornado Alley, which is the Great Plains, but that's kind of a misnomer, because that's kind of where tornadoes are studied the most, because they're easier to study out there. But anywhere from Georgia, to Alabama, to Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee, westward into Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Iowa, all of those areas get about the same relative frequency of tornado.

James Elsner is a climate expert and Geography Department Chair at Florida State University. (Photo: Courtesy of Florida State University)

CURWOOD: Us humans are famous in saying, well, that's probably not going to affect me, the odds are pretty low. To what extent to people have that response to the risk of tornadoes, do you think?

ELSNER: Well, I think they haven't. Because it's, it's true. I mean, if you look at even some of the most tornado prone regions of the country, in the southeast into the Great Plains, the chances are probably one every 500 or 600 years that you're going to get hit by a tornado. And so it's a fairly rare event. But when you start to see it at the scale of a city, or a community or a state, you're going to see this kind of destruction and so it is hard for people to get their heads around, it could happen to me when the chances are, it's not going to happen to them.

CURWOOD: Tornado expert in Florida State University Professor James Elsner, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

ELSNER: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- More about James Elsner

- Tornado statistics on NOAA’s Storm Prediction Center

- Climate Dynamics Study | “The Increasing Efficiency of Tornado Days in the United States”

- New York Times | “Alabama Tornado Among the Region’s Worst in 30 Years”

[MUSIC: Frank Ocean, “Thinkin Bout You” on Channel Orange, Def Jam Records]

Beyond the Headlines

The Margaret Pace Park is one of Miami’s public lands which will no longer be treated with glyphosate herbicides. (Photo: Ryan Healy, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So now it's time to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an intrepid editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. He's on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hi there. Peter. What do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. Let's start with an item from Miami. Last week, the city of Miami banned the use, by its city government, of herbicides containing glyphosate. That's the main ingredient in Roundup, the leading weed-killing product for homes and gardens in the US and around the world. Miami Beach and the city of Stuart, about 100 miles north of Miami, had already banned it.

CURWOOD: And why does Miami say that glyphosate’s not something they want their city employees to use anymore?

DYKSTRA: Well, glyphosate is considered to be so effective at killing vegetation on land; they're concerned that it would also kill vegetation in Biscayne Bay.

CURWOOD: And what about human health effects?

DYKSTRA: Well, the World Health Organization of the UN has said that glyphosate is a probable carcinogen. Last year in California, a groundskeeper won a $78 million judgment. He convinced the jury that his lymphoma had been caused by his constant exposure to glyphosate on the job.

CURWOOD: And there could be a lot of people exposed. I mean, it's used in lawns, and golf courses, and almost everywhere. What do you have next for us?

DYKSTRA: Well, we're going to talk a little bit more about golf courses, because one of my favorite running stories has come to an end after about 11 or 12 years, or at least we think it's over. Donald Trump's Scottish golf resort in Aberdeenshire has been ordered to pay legal costs for both sides. The Trump Organization had sued a wind farm developer who put 11 wind turbines offshore. Trump said it ruined the view. Not only is it over, but he's going to have to pay extra for bringing lawsuits.

CURWOOD: I think the President Trump has a number of legal bills these days doesn't he?

DYKSTRA: Yep.

CURWOOD: Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: In 2004, Hurricane Ivan tore up the Gulf of Mexico floor and unleashed America's longest lasting oil spill about 12 miles off the coast of Louisiana. Taylor Energy operates some wellheads there. They're suing the federal government contractor that's charged with trying to cap these wells. It's kind of a relatively slow leak, 700 barrels a day is the estimate. That 700 barrels a day has been over 15 years. And if you add it all up, the amount of oil spilled could approach the size of the Deepwater Horizon spill back in 2010.

CURWOOD: And why is the company suing?

DYKSTRA: They claim in litigation that the government's plan to cap the wells could actually make the spill worse. In the meantime, nobody's been able to deal with the oil spill for 15 years.

CURWOOD: Time now to take a look back at the history vault. Peter, what do you see today?

The Exxon-Valdez oil spill happened 30 years ago in Prince William Sound, Alaska. 10.8 million gallons of crude oil were spilled after the Exxon-Valdez oil tanker ran aground. (Photo: Arlis Reference, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: More oil spills. 30 years ago, later this month, the anniversary of the Exxon Valdez spill, the biggest in US history until Deepwater Horizon in 2010. They're still finding oil today. And fisheries like the herring fishery have never fully recovered.

CURWOOD: And what about the people? I think there's some spill victims who… Well, the court awarded them a lot of money, but I'm not sure they ever saw it?

DYKSTRA: This spill has literally cost billions to Exxon Mobil either to clean up the mess as best they could, or in paying thousands of victims in Alaska. Some of the settlements were in the millions, but it took 20 years to get it through the courts. So about one-fifth of the people who received settlements died before they got their check.

CURWOOD: And what happened to the captain, by the way, of the Exxon Valdez?

DYKSTRA: Oh, Captain Joe Hazelwood had gone away to his cabin. He was drunk, let a third mate, an unlicensed third mate, bring the boat through Prince William Sound. Captain Hazelwood was convicted of one count of negligence, and guess what he ended up doing? Teaching a marine safety course at a college in Long Island.

CURWOOD: Indeed Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Well, thank you, Steve. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Miami New Times | “Miami Bans Controversial Herbicides That Are Killing Biscayne Bay”

- BBC | “Scottish Government Wins Donald Trump Wind Power Legal Costs”

- The Chicago Tribune | “The U.S. Is Making an Effort to End the Longest Oil Spill in History. This Company Is Fighting Against It in Court.”

- History.com | “Exxon-Valdez Oil Spill”

[MUSIC: Snarky Puppy, “The Curtain” on Sylva, Backed by the genre-crossing Metropole Orkest, Impulse Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Fish don’t breathe air but they do need oxygen, and the ocean has less of it these days. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jacqueline Schwab, “Mad Robin” on Mad Robin, traditional English, Midsummer Records]

Oceans Losing Oxygen

A swirling green phytoplankton bloom in the Baltic Sea traces the edges of a vortex, July 18, 2018. Algae blooms now regularly cause dead zones in the basin. (Photo: Joshua Stevens and Lauren Dauphin / NASA Earth Obervatory)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

One of the most far-reaching consequences of climate change is ocean warming. Higher ocean temperatures affect everything from fish health to hurricane strength, and worsen sea level rise because of a phenomenon called thermal expansion, that could add a full foot to sea level rise by the end of the century. And warmer ocean temperatures are even changing the chemistry of the ocean itself by reducing the amount of oxygen in the water. Pollution is also depleting ocean oxygen. Here to explain is Denise Breitburg, she’s a Senior Scientist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Denise, welcome to Living on Earth!

BREITBURG: Oh, thank you.

BASCOMB: So Denise, what's going on here? How much have ocean oxygen levels declined in the last few decades?

BREITBURG: Well, since the 1970s, the open ocean has lost about 2% of its total oxygen content. That may not sound like a lot, but that's 150 billion tons of oxygen. And then during the same time, we have recorded occurrences of low oxygen in over 600 coastal sites around the world, places like estuaries and inland seas.

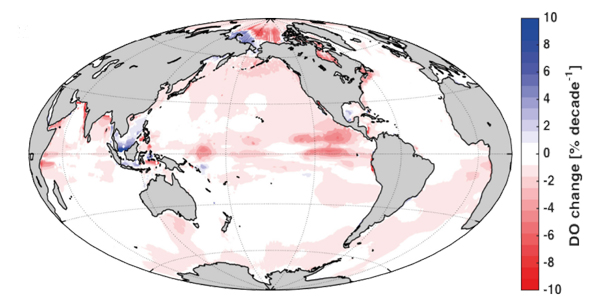

Dissolved oxygen changes in the oceans over the past five decades. While oxygen has increased in some locations, overall the world’s oceans are losing oxygen. (Image: Schmidtko, S., Stramma, L. and Visbeck, M., 2017. Decline in global oceanic oxygen content during the past five decades. Nature, 542(7641), p.335.)

BASCOMB: And how does that less oxygen actually affect ocean creatures? Can you give us a couple examples?

BREITBURG: The best way to think of the effect of oxygen decline on creatures that live in the ocean is by the old motto of the American Lung Association, which is "if you can't breathe, nothing else matters". So low oxygen affects the ability of organisms to survive in the ocean, it affects where they live. It affects where they're fished. And for microbes, it really affects how they influence the chemistry of the ocean. So when oxygen is really low microbes in the ocean will produce things like methane or nitrous oxide that are really potent greenhouse gases.

BASCOMB: And why are oxygen levels in decline?

BREITBURG: There are two main reasons. One is that the earth is getting warmer. Warm water can't hold as much oxygen as cool water can, and warm temperatures also make it much harder for oxygen from the atmosphere to mix into deeper water. The other problem is that we are discharging way too much nutrients into our coastal waters. You can think about nutrients as fertilizing a lawn; a little bit is you know, not damaging, it can stimulate growth. But as we put more and more nutrients in from sewage, from burning of fossil fuels, and from agriculture, we are growing way too much phytoplankton; way too much biomass is created. And as that decays, the decay process uses up oxygen.

BASCOMB: And then you're looking at dead zones?

BREITBURG: Right, they're dead zones when you think about where fish and crabs and things like that can live, they're not dead in terms of microbes. It's great habitat for microbes that live in the absence of oxygen or where oxygen is incredibly scarce. So basically, energy from the ecosystem that would be going into production of fish and corals and all those kinds of organisms that we normally think of living in the ocean, instead get shuttled into microbes.

A phytoplankton bloom in the Chesapeake Bay in 2014. (Photo: Joshua Stevens and Jesse Allen / NASA Earth Observatory)

BASCOMB: And you've studied the problem of dead zones in the Chesapeake. Can you tell me about some of the impacts that you're seeing there?

BREITBURG: In the Chesapeake Bay during summer, oxygen concentrations are really low in bottom waters in the middle of the bay, in some of the tributaries, and at nighttime, even in really shallow water. And when oxygen is low, things that can swim away do, and animals that can't avoid the low oxygen die, or they don't grow as well or they're more susceptible to disease where oxygen is really low in the dead zone. Instead of waters filled with fish and jellyfish and all kinds of animals swimming around, it's empty and silent.

BASCOMB: What about the very base of the food chain in the ocean, zooplankton -- how are they impacted by lower oxygen levels?

BREITBURG: Zooplankton will often avoid low oxygen if they can. But it's critical to their ability to use habitat and some new work that has been done out in the open ocean in some of these low oxygen areas shows that even small changes, just a small further decrease in oxygen can completely exclude these animals.

BASCOMB: How troubling is that? I mean, zooplankton, of course are eaten by tiny fish which are eaten by larger fish and so on up the food chain, until you get to whales and sharks at the very top.

BREITBURG: Low oxygen can completely change the way food webs operate. They can control whether things like zooplankton are available to fish to eat, they can control whether they are able to escape predators or become more sensitive. And we also really worry that for fish and other things that are targets of fisheries, low oxygen can actually make them more susceptible to becoming overfished.

Low oxygen levels cause fish kills in the Chesapeake Bay and other coastal waters that experience phytoplankton blooms. (Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: And how might lower oxygen levels ultimately impact people that rely on fish for their subsistence or commercial fishermen?

BREITBURG: We really worry that low oxygen can make fisheries less sustainable and can have negative effect on fishing communities, especially ones that are very dependent on local resources. If you have a fishery that's, you know, highly industrialized, can move to where the fish are, they may be able to catch fish in spite of low oxygen, but even there, there's potentially a problem. If fish are avoiding low oxygen areas, they're becoming more concentrated in areas with higher oxygen which may be closer to the surface or if we think about the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, they can become really abundant around the edges of the dead zone. Fishers know how to target these areas. And so what oxygen can do is it can concentrate the fishing fleets and the fish or shrimp into the same area, make it easier to catch them. And then we really worry about overfishing.

BASCOMB: So it's literally like shooting fish in a barrel.

BREITBURG: Yeah, it can be like that.

Oysters are an important part of the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem and help clean the water, but they are particularly vulnerable to low oxygen, which appears to suppress their immune systems. (Photo: Steve Freeman, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, Denise, what can be done about this? I mean, what can we do to address this problem of declining oxygen levels in the world's oceans?

BREITBURG: There are two basic things that we need to do. The first is to reduce nutrients coming into coastal waters, from agriculture, from fossil fuel burning and from human waste. And these are all things that have real direct human health benefits if we take those steps as well as benefits to the ocean. So if we are doing a better job at sewage treatment that makes for a much cleaner environment that is less likely to cause health problems for humans. For agriculture, there are practices that can reduce the amount of nutrients nitrogen and phosphorus that are added to our waterways while still producing the food that the growing human population needs. The other major thing that we need to do is to take the steps needed to reduce the problem of global warming and reverse the trajectory that we're on.

BASCOMB: So stop the warming of the oceans, you know, that would go quite a long ways in addressing this problem.

BREITBURG: We absolutely need to stop the warming of the oceans, both for the sake of the oceans and for the sake of the human population that's on land.

BASCOMB: Denise Breitburg is a senior scientist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Thank you for taking this time with me.

BREITBURG: Thank you so much.

Related links:

- Scientific American | “The Ocean Is Running Out of Breath, Scientists Warn”

- Science | “Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters”

[MUSIC: Stan Samole, “Row Row Row Your Boat” on Childish Dreams, public domain, Jazz Inspiration Records]

Note on Emerging Science: Matchmaking for a Frog Named "Romeo"

Scientists hope that the surviving Sehuencas frogs have developed genetic resistance to the chytrid fungus. (Photo: Juliet by Robin Moore, Global Wildlife Conservation)

CURWOOD: Just ahead, cloning ancient redwood trees that appear to be dead but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: A group of scientists from the University of Maryland recently announced the discovery of a Bolivian frog species that was believed to be extinct in the wild. Although one Sehuencas water frog, named Romeo, survived in captivity, the species hadn't been seen in the wild for 10 years. Scientists blamed chytridiomycosis, a fungal disease that has wiped out frog populations around the world. But researchers found five of the frogs in a cloud forest in the Bolivian mountains. They speculate that the five surviving frogs may have immunity or genetic resistance to the deadly fungus.

Juliet, the Sehuencas frog (Photo: Robin Moore, Global Wildlife Conservation)

The frogs' survival could also be due to an environmental factor, like an unusually warm microclimate that was not conducive to the growth of the fungus. There's currently no way to eradicate the chytrid fungus in the wild, so scientists are eager to study the surviving frogs and to try to breed them as part of a captive conservation breeding program, possibly resulting in Sehuencas frogs that are resistant to the deadly fungus. The discovery gives researchers hope that more Sehuencas water frogs might be found in the wild. It also gives scientists a chance to help the species recover, and to introduce Romeo to one of the female frogs, who they've appropriately named Juliet. That's this week's note on emerging science. I'm Don Lyman.

Related links:

- Lonely No More: Romeo the Sehuencas Water Frog Finds Love

- Romeo, Oh, Romeo!

- Science News | This Rediscovered Bolivian Frog Species Survived Deadly Chytrid Fungus

Cloning Giant Sequoias

Photo of a Sequoia sempervirens trunk. (Photo: Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Around 3,000 years ago the Mayans were just getting started with their temples, Rome was still rural farmland, and it would be another 1000 years ‘til Jesus walked the earth. But also around 3000 years ago in the Pacific Northwest a seed fell and from it grew a massive sequoia tree. Giant sequoias and other redwood trees are endemic to the Pacific Northwest and many were standing there long before white settlers came to the region. And when settlers arrived they found trees more than 30 feet in diameter and hundreds of feet tall, perfect for lumber. Most have been cut down but now researchers have found a way to clone both the living giants as well as some ancient, seemingly dead, trees. Here to explain is David Milarch, co-founder of Archangel Ancient Tree Archive. David, welcome to Living on Earth.

MILARCH: Thanks for having me. It's an honor and a pleasure. It really is.

BASCOMB: So people may have seen old photos of redwood trees. You know, there are 30 or 40 people standing across one and over the top of them. But for someone who's never experienced a living redwood, can you describe redwood trees and what it's like to be in a grove of them?

MILARCH: Well, first and foremost, they're magical. They're enormous. And most people that we've taken to old growth redwood forests, the first thing that everyone has in common is they go completely silent. It's stuns you. They are so huge, up to 400 feet tall, 30 foot wide trunks. And then the next thing most people do is they walk up and they want to put their hand and touch the tree. And as soon as they put their hand up and touch the trees, then they go, wow, this is incredible.

BASCOMB: And what got you started with this project of cloning redwoods? What was the catalyst for that?

MILARCH: 25 years ago, the storm flags were flying on climate change, you know, we've known about climate change since the 60s. And I decided, we had two small children, we needed to find answers to reverse climate change. That's what started this project, finding the answers to reverse climate change.

BASCOMB: And how do redwoods play into that?

MILARCH: Redwoods sequester about 10 times the amount of CO2 that normal trees do. They grew up to 10 feet a year, they grow up to 3-4,000 years old, and they're working 24/7, sequestering CO2 and producing oxygen. And for, like, the Giant Sequoias that we've done, 40% of their dry weight is stored CO2.

BASCOMB: Wow.

MILARCH: So, they're about 1,000 tons apiece. So, 400 tons of that tree is stored excess CO2. That really adds up.

BASCOMB: And what are some of the other trees that you're looking at that are really good at sequestering carbon dioxide?

MILARCH: Giant Sequoia, the Cowrie trees down in New Zealand, Cottonwoods and Aspen's grow very quickly and they're one of our best hopes here in North America for sequestering CO2 on dry and arid land, some of the birches grow very, very quickly. So, it's usually the fastest growing, longest growing, healthiest trees that we're looking for that'll store the greatest amount of CO2. So that's a few.

Co-founder David Milarch of Archangel Ancient Trees Archive. (Photo: Courtesy of Archangel Ancient Tree Archive)

BASCOMB: From what I understand the first Redwood fossils date back to about 200 million years ago. But currently they're endangered or at least their populations are in demise. What happened with them? Is it just settlers coming along and cutting them down, or what happened with the redwoods?

MILARCH: It's real simple: man's greed. We have cut down 96% of our old growth redwood forest. For hot tubs, for lumber. And most of it went over across the Pacific. And there's vast quantities of it on the bottom of the ocean in the bays in China, getting ready to be utilized when the price goes up even more. So we've squandered it. We've cut them almost all down in the name of profit. That's before we even realized how great a promise they hold right now when climate change is just really starting to get going. So thank goodness, we decided to try and bring the old growth forests back. When we started 25 years ago, we were almost laughed off the face of the planet. You cannot clone 1,000 year-old, 2,000 year old-trees that we were told. It's like a 115 year old woman trying to have a child. It won't work. We've tried. You're wasting your time. Go back home. That's what we heard from most academics and most forest service people. So we blundered on and we broke through. And I'm happy to say we have cloned 130 different species of trees, all champion trees, the largest and oldest of their species.

BASCOMB: So how do you make a clone of a 3,000 year old Redwood tree?

MILARCH: Well let's begin here. Almost every tree on the planet is self-cloning. What we're doing is just hurrying up the process. We're not changing the DNA at all, we're not doing anything other than nature would do itself. But how we do that is we send climbers to the very tops of these trees, and out to the very ends of the branches. And we found that if we gather this year's new growth, the hormones and chemicals that go through these trees that don't allow them to be cloned haven't gotten there yet. So our climbers bring them down, we rush to a FedEx or somewhere where we can overnight them back to Copemish, Michigan, to our lab. And the very next day we start to work our magic on them, and we're asking them to form roots or to self-clone.

BASCOMB: So the cut down redwoods are they also sending out shoots?

MILARCH: Yes, those are called basal sprouts. But that's a whole different story. One of the trees we worked on were the Coast Redwoods. The coast redwoods have a 500 mile native range from the Oregon-California border, south, down to Big Sur. That's the only range of Coast Redwoods on the planet. Well, we drove and walked that entire 500 mile range. But something different. We look for redwoods, Coast Redwoods on private property.

BASCOMB: Why?

MILARCH: Because the little remnant forests here and there the Coast Redwoods that were saved. When we asked to try to be able to clone those on state and federal land, they said no. So we said. Well, all right, we'll look on a private land. And thank goodness we did. Because the biggest Coast Redwoods and the biggest giant Sequoias are not on state and federal property. They're on private property. One day, my son, Jake Milarch, and I, and Michael Taylor. We were searching for Coast Redwoods and we happened upon a valley. And in this valley behind some people's homes, we found enormous stumps.Trees that were 30 to 35 foot in diameter. Across the top of the stump, a very, very large Coast Redwood was a 20 foot diameter Coast Redwood here we found Coast Redwoods that we're 10 feet or so bigger in diameter than General Sherman, the largest tree on Earth. These were cut down in 1870, and lost. Nobody knew they were there, we stumbled across them. So after I got my composure, and my son walked up to the 35 foot diameter stump, he said, hey, Dad, we should try and clone these. I said, well, Jake, we're pretty good, but these have been cut down for 100 years. He goes, yep, but there's still life in 'em. Let's try.

Sequoia sempervirens seedlings post cloning methods. (Photo: Courtesy of Archangel Ancient Tree Archive)

BASCOMB: So how do you make a clone of a dead tree, though? I mean, there's some life in it, he said. But where does that life come from?

MILARCH: Well, the beauty of redwoods is that they almost refuse to die. You can't burn them down. They withstand stand fire. Disease hardly ever attacks them. You can dynamite them, you can cut them down, but they'll cling to life and they know that on their way out, the mother tree, when she is attacked, and it's life threatening, she'll send up what's called basal sprouts. So out of her trunk, or out of the root system, she'll send up basal sprouts and she'll self clone herself. So we found the basal sprouts, my son did, we took living tissue of that, sent it back to the lab. And I'm happy to say that we have found five different stumps, 30 feet in diameter, across the top, and larger that we've now made thousands of clones. Those trees live on now in seven countries.

BASCOMB: Now, how old are those trees? If they're that much bigger than the other trees, you're saying, how old are they? And and if you could maybe put that into context. I mean, what was happening in the world when these trees were just sprouting and getting going in life?

MILARCH: Well, the trees of 30 foot diameter the Coast Redwoods was we figured to be 2,500 years old. So when Jesus walked the earth, they're already 500 years old. The giant Sequoias is that we found in the Lost Grove, on the very top of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, they are between 3-4000 years old.

BASCOMB: What are the advantages of cloning these ancient trees as opposed to just growing them from seed?

MILARCH: Most Coast Redwoods don't live to be 1000 years old. The ones we're cloning are 2000, 3000 years old. And nobody knows how they were able to do that. Their DNA has never been studied, but doesn't it make sense to us the biggest, oldest, strongest trees that live two or three times the normal age of their species to put those genetics back into our forests?

BASCOMB: What is the future for your work? I understand that you're working in other countries and you have high aspirations but what are you your goals here?

MILARCH: We plan on working in New Zealand this coming year, and Australia. They're just screaming down there for our trees and for us to come down and help preserve their trees. So we're going to do a fundraiser to get down to New Zealand and do the Cowrie Trees. And Australia has pledged to plant a billion trees, they like to plan a bunch of their native clones, so. And, God willing, the funding will come in and we'll be able to go out around the world this year as we planned and teach a lot of the children and get a lot of this work done.

BASCOMB: What motivates you to do this work?

MILARCH: Going after workable, doable solutions to reverse climate change. I don't want to leave this planet and leave my children and my grandchildren, or the world's children and grandchildren, to have to to go through the nightmares that the scientists are predicting. I can't do that. So as long as I draw breath, I will do everything in my power to avert this so everyone's grandchildren don't have the future that some are looking at. We can do better.

BASCOMB: David Milarch is Co-founder of Archangel Ancient Tree Archive. David, thank you so much for sharing your story with me.

MILARCH: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Archangel Tree Archive Website

- Washington Post | “Decoding the Redwoods”

- Huffington Post | “Redwood Trees May Help Battle Climate Change, Study Finds”

[MUSIC: Tony Trischka, “Ocracoke Lullabye” on Great Big World, Rounder Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – In search of the canary trees of Southeast Alaska.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay Tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ruben Gonzalez, “Siboney” on Introducing…Ruben Gonzalez, by Ernesto Lecuona, World Circuit Nonesuch]

In Search of the Canary Tree

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Alaska, the “Last Frontier” state, is one of the first frontiers when it comes to the impacts of climate disruption. Over the past sixty years the state has warmed an average of three degrees Fahrenheit, but an average of six degrees in winter, according to the EPA. That has devastated a key species found in temperate rainforests: the Nootka cypress. Many people also call it the yellow cedar. In her new book In Search of the Canary Tree, author Lauren Oakes traces her quest to understand how forests, and the people who depend on them, are adapting to the widespread loss of this tree.

OAKES: I came to Alaska looking for hope in a graveyard. Ice melting, seas rising, longer droughts, in a world seemingly on fire, I chose to put myself in some of the worst of it. The Alexander Archipelago in Southeast Alaska is a collection of thousands of islands in one of the scarce pockets remaining on this planet, where thick moss blankets the forest floor and trees range from tiny seedlings to ancient giants.

But I wasn’t loading into a Cessna 4-seater to look for fairytale forests of spruce, hemlock, and cedar. I was flying in search of the forests I’d study. The graveyards of standing dead trees and the plants I so wanted to believe could tell me, through science, that maybe the world is not coming to an end.

“In Search of the Canary Tree” is Lauren Oakes’ first book. (Image: The Hachette Book Group, Inc.)

CURWOOD: Author Lauren Oakes joins us now from Bozeman, Montana. Welcome to Living on Earth!

OAKES: Thank you. It's a pleasure to be on the show.

CURWOOD: So in your book, you describe what you call an eerie sight of the standing dead, the yellow cedar trees that have died in massive numbers in recent decades. Why is this going on?

OAKES: So it's an interesting story, a little bit counterintuitive when it comes to climate change, because they're essentially dying as an impact from freezing events. And that seems a little bit weird in a warming world. But in the Pacific Northwest, what we're seeing in terms of climate change is an increase in precipitation as rainfall and a decrease in snow. And snow basically acts as an insulator, a blanket on their roots. These trees have really shallow root structures, and they tend to be found in these kind of boggy, more wet soils. And so in the springtime when you get earlier warming, the trees basically de-harden and they're thinking, Okay, it's ready for summer. It's like taking off your winter coat. But it turns out that there's still some cold events that come in and persist in spite of climate change and those come from the interior or off the coast. And it's that combination of events where you have the roots vulnerable without their warm blanket on them, and then a sudden cold snap, that damages them and their ability to update nutrients.

CURWOOD: How would you describe a yellow cedar tree and the southeast Alaskan coast where you studied them?

Yellow cedar foliage. (Image: Kate Cahill)

OAKES: Well, Southeast Alaska is just -- I do hold it near and dear to my heart. It's a beautiful landscape in a place that feels more remote than really anywhere else in the world I've been. Many of the communities are accessible only by boat or plane, so there's also a real sense of community in the towns because people are living, you know, more connected to one another and perhaps, you know, more disconnected from the rest of the state or even from the country. But in terms of weather, sure, it's a coastal temperate rainforest It gets a lot of rainfall, it's damp, it can be cold, summers are starting to see more sunshine and there certainly have been some sunny summers in recent years. But you also do get a fair bit of rain. And the trees themselves are quite distinct. Dr. Paul Hennon was one of the people that I worked with, and he ends up being a character in the book; he used to tell me early on, Well, when you fly in a plane for the first time, you're going to be able to tell which one's a yellow cedar tree, and which one's not. And I thought that was kind of crazy, could you really distinguish a tree from the top, flying in a plane? But the truth is, yes, they have a different color. They have these sweeping limbs that hang down, so from above, as a bird's eye view, they look quite different. And standing underneath them, they're just beautiful.

CURWOOD: What drew you to study how forests are responding to the yellow cedar die-off?

OAKES: I was attracted to work in the north because, well at the time there was a lot of attention on the poles because the poles are warming at faster rates than the global averages. And I thought going in that I wanted to do a project up north, climate change-related because I felt there was a need. And I also thought that potentially there could be lessons there for elsewhere. But I really didn't know what I would study. And I spent a summer of doing exploratory research, trying to talk with people about the kinds of climate impacts they were facing. And in that process, I met Dr. Paul Hennon, who is a forest pathologist with the United States Forest Service. And he was just about to publish, basically a synthesis of 30 years of research showing that climate change was linked to the death of these trees. And for me, that seemed like a perfect starting point for the question of what happens next, what happens in the forest community? How does it develop in response to the death of these trees? And then also, how are people coping with those changes -- are they coping with those changes and in what ways?

A landing beach in Klag Bay, north of Slocum Arm on Chichagof Island where a yellow cedar dieback occurs. (Photo: Lauren Oakes)

CURWOOD: A lot of people don't want to look at the mouth of a monster, and certainly climate disruption is a monster that could devour our civilization. Why you? Why Lauren Oakes saying, hey, let's see what happens here?

OAKES: There was an attraction to me of learning in place, of spending time in a community to understand both effects on the environment and people, on the relationships between them. And why look towards the future? I feel like that's where we need to be looking, and there's often a tendency to think more short term, but we've been lagging for a while now. And now a lot of those impacts that seem far off are here and we need to figure out how to cope with them.

CURWOOD: So let's talk about your research. What did you find was happening in the forest in response to the yellow cedar die-off?

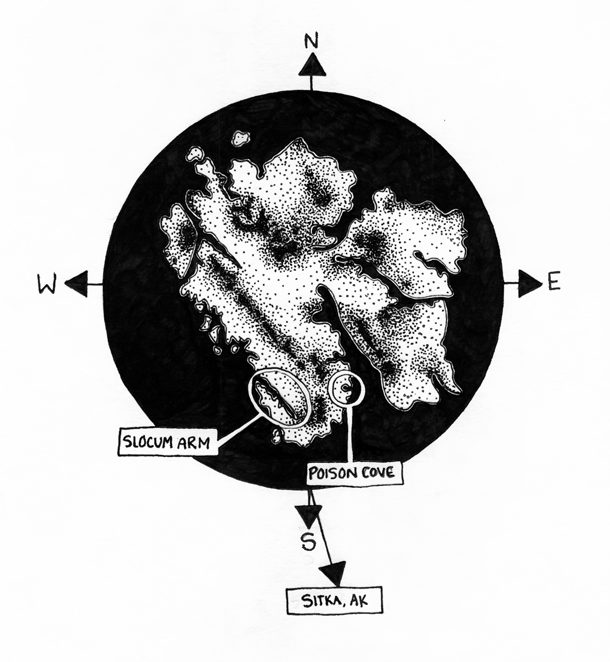

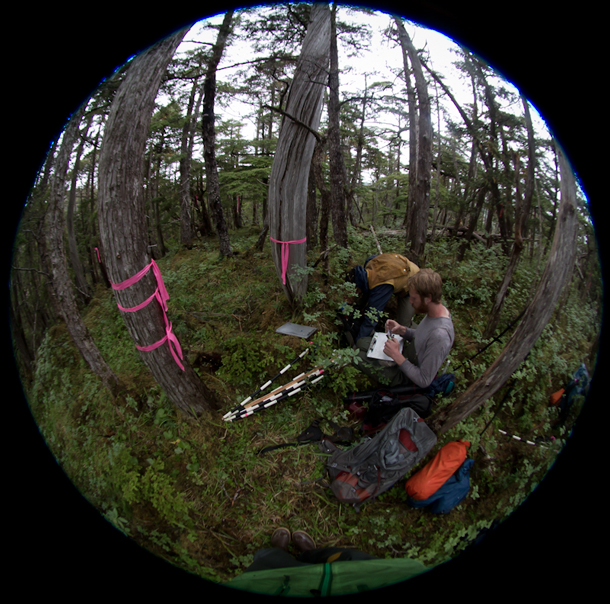

Lauren Oakes conducted much of her research on Chichagof Island, off the coast of Southeast Alaska. (Image: Kate Cahill)

OAKES: Well, there were a couple things that were surprising. The first is that not all the yellow cedar trees in the forest affected are dying, there are still some survivors. So in some of my sites, on average, about 80% of the trees were affected, but that leaves 20 that were still doing okay. And then of course, there are still some pockets where you'll find healthy populations -- up in Glacier Bay National Park, a strong population of healthy, thriving individuals. So that speaks to me of, you know, the effects of microclimate, how it's variable. And ecologically that was interesting to me. But now, philosophically, in writing the book, I thought about it in terms of, Okay, well, what does that mean for people? Will there be places where we're impacted more than others, and places where we need to care for one another, reach out for one another; and places where we still may be able to thrive. So that was one finding. But another was that despite the loss of these trees, there is a flourishing forest. That it takes time for it to recover and to grow into something new, but ecologically what I saw was another conifer species, Western hemlock, taking over so ultimately these trees would grow into the gaps created by the yellow cedar trees. In the field we call them hugs, because you could literally see this Western hemlock tree that had started as a little tiny sapling right next to a dead yellow cedar and grown up so close to it that its branches just reached around the trunk of the dead one, reaching towards the light. There were also changes in the understory plant community. So initially following the death of the trees, you tend to lose mosses and bryophytes, those real, you know, sponge-like members of the plant community, when you think of these kind of dreamy rain forests. They may be responding to the increase in light that then reaches the forest floor. And you see an increase in shrubs -- things like vaccinium, and menziesia, and also some forage that deer rely upon.

CURWOOD: So what did you find out in terms of why it mattered if the yellow cedar turned over to hemlock -- who was affected by that and how did they respond?

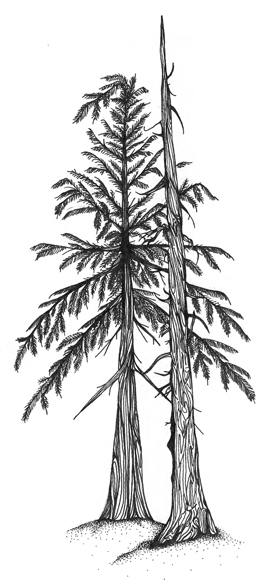

A Western hemlock growing up beside a dead yellow cedar, in what scientists casually refer to as a “hug”. (Image: Kate Cahill)

OAKES: Yeah, so partly how people were affected depends on their relationship to the trees. So there's two kinds of attachment, they call it nature attachment, actually, emotional or functional, right? So the emotional is that we have a connection to place, to maybe a trail you hike, or something in your own backyard. And the functional is, you know, more like ecosystem services, what a resource, if you will, provides us: the water we draw from it, or the wood we use from a tree. And so people's relationships to these trees, in part, had influence on how they responded. And the ones who had these emotional ties had a process of grief associated with it. And they were not only losing some of their cultural heritage, for example, or, you know, recreation interests, but also a real relationship that some might only attribute to something we have with other people. And I went into it studying what's called the KAB or the knowledge-attitudes-behavior framework, and it's something researchers use to look at what might cause behavioral change. So for example, it's used in human health to say like, what might motivate someone to change their diet or in the environmental world; what about recycling? What can motivate somebody to recycle? And the theory is that if we're knowledgeable about something, we'll have certain attitudes or be concerned about it. And then that will motivate behavior. Sometimes it holds true and sometimes it doesn't. So I went in thinking, how knowledgeable are people about these impacts? Do they know that it's caused by climate change? If they do, does that affect their attitudes about it? And what do we see in terms of behavioral change or adaptation?

CURWOOD: And the answer was?

OAKES: Well, I definitely found that people who were knowledgeable of the impacts and knew that they were caused by climate change responded differently. They were, yes, making changes in their own community. So for example, innovating their business to make use of other species or make use of the dead trees or changing their use of the forests through recreation, or hunting, etc. But they were also more concerned at a global level. They acknowledged that this, you know, seemingly distant, massive, unwieldy, somewhat unwieldy thing we call climate change was really hitting home and that often led them to be more likely to engage in global actions -- which could be educating others about climate change by using the trees as an example; feeling more motivated to reduce their home energy use; do things like biking to work. So that's in some ways where the canary in the coal mine comes from. This tree became the canary in the coal mine for the people I interviewed, but then also for me, and my writing process. And you know, I hope also for the readers in the future.

CURWOOD: And for those who didn't really understand that this is related to climate disruption. What did they tell you?

OAKES: Yeah, so you might see, if they knew of the changes occurring, so they could see the dead trees, they had access to them, and they used the trees in various ways, they still might innovate and make use of the changing environment. But that aspect of the link to global action was missing. And they also didn't face a whole suite of psychological responses. So the people who were knowledgeable that climate change was impacting these trees had another level to deal with, which was coping with the knowledge that this is climate change. And that seems negative. But I also see it as a positive because it's part of a grief process. It's part of acceptance and in any grief process, we're accepting loss but also looking towards what new life is created. How do we adapt to these changing conditions and how to the relationships in them vary?

Lauren Oakes’ research colleague Odin Miller checks the data he recorded from surveying understory plants. (Photo: Lauren Oakes)

CURWOOD: What advice do you have for our listeners who might feel, let's face it, pretty exhausted from the constant onslaught of bad environmental news, especially the notion that our climate is really starting to spiral out of control towards a very uncomfortable place.

OAKES: Yeah. So what motivated me to write the book was that when I finally finished the research I was doing, I still felt like I was struggling with this question of how do you live with what you know, as a scientist now, and a citizen? And do you have hope about the future? I am like many others in that I feel like the headlines are tiring and exhausting, and have a lot of doom and gloom in them and make us think that the whole future on climate change is quite dark. And yes, there are dark impacts coming but I also realized in both my research process and in my personal process of trying to sort out how do I live with this knowledge is that I want to put myself in the camp of someone doing something, someone feeling like we still can make a difference and cope, and think about what that means in terms of my own actions. So a lot of us are kind of waiting for top down decisions to come, whether that's our president finally acknowledging climate change, or as a world meeting the Paris Agreement, but I think there's a lot that we can do at the local scale, both in terms of mitigation and in terms of adaptation.

Lauren Oakes is a conservation scientist at the Wildlife Conservation Society and an adjunct professor in Earth System Science at Stanford University. (Photo: Clayton Boyd)

CURWOOD: So how fair is it to say that one secret for happiness going forward might be resiliency?

OAKES: For sure. Yeah. So one of the things I write about in the book was that I had this series of questions where I was asking people about their future outlook. And I asked them a series of three questions. And I wanted to know, what was the environmental problem they were most concerned about? And did they think that there was a lot or nothing that we could do about it? How optimistic were they about the future. And I say in the book that I never had scientific results from that. So there were a lot of people who identified climate change. And of them, some of them were really optimistic and some were completely negative. So the scientist in me said, Okay, I could go back and interview more people or there should be a bigger study here. But instead I took it as a personal lesson that we have a choice, every day in how we wake up and face this world and the problems that we have. And I want to put myself in the camp of people who feel optimistic, who are looking for opportunities who can make a difference, even if it's at a tiny tiny scale.

CURWOOD: Lauren Oakes is a conservation scientist at the Wildlife Conservation Society. Her new book is called In Search of The Canary Tree. Lauren, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

OAKES: Thanks for having me.

Related link:

“In Search of the Canary Tree: The Story of a Scientist, a Cypress, and a Changing World”

BASCOMB: Next time on Living on Earth, a prize-winning climate scientist sounds a warning.

MANN: Some would argue that the assault on science that we were dealing with has now metastasized into something larger in our politics today, which is an assault on truth -- objective truth, and facts.

BASCOMB: Hear Michael Mann, climate scientist and winner of the 2019 Tyler Prize next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Snarky Puppy, “The Curtain” on Sylva, Backed by the genre-crossing Metropole Orkest, Impulse Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Delilah Bethel, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth