May 18, 2018

Air Date: May 18, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

FDA Scientist Finds Weed Killer on Many Foods

View the page for this story

The herbicide glyphosate is considered to be a probable carcinogen by a World Health Organization agency and it is widely used for household and commercial applications. New e-mails uncovered through a Freedom of Information Act request by journalist Carey Gillam reveal that an FDA scientist found glyphosate residue on nearly every food item tested, including cereals, crackers, and honey. Ms. Gillam discusses with host Steve Curwood her concerns for public health and why the FDA has not made these data public. (08:35)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood go Beyond the Headlines to discuss China’s high-rise hog farms and the salt water intrusion threatening one of California’s most agriculturally productive lands. And they remember a distinguished nineteenth century London scientist who was an early observer of global warming and the heat island effect of cities. (03:50)

Cool Fix for a Hot Planet: Storing CO2 in Rocks

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Scientists are studying how rocks might capture and store a greenhouse gas to help cool the planet. Solidified lava and magma could perhaps safely store carbon dioxide, through a chemical reaction that forms a stable solid carbonate from the climate-warming gas and the rock. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering reports. (02:45)

UN Climate Talks Gear Up for December

View the page for this story

The 190 or so nations in the Paris Climate Agreement will come together in December at a summit in Poland aimed at agreeing on rules to implement the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015. Negotiators recently met in Bonn to try to iron out any disagreements in advance of the high-level session. Host Steve Curwood and Union of Concerned Scientists Policy Director Alden Meyer spoke about progress in Bonn and the road ahead. (07:20)

BirdNote®: Dippers on the Elwha

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Many species in the Pacific Northwest benefitted from the removal of Elwha River dams, among them American Dippers, as Mary McCann explains in today’s BirdNote®. (02:00)

Nepal’s Threatened Wetlands

View the page for this story

The lofty Himalayas give rise to an intricate system of rivers and lakes that make Nepal rich in wetlands. These are critical habitats for migrating birds and rare species like the Bengal tiger and one horned rhino, but the wetlands are not well protected and face numerous threats from development to climate change. Ramesh Bhushal of the online magazine Third Pole describes to host Steve Curwood these wetlands at risk. (04:40)

Saving Kerala's Fresh Water

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Like much of South Asia, the Indian state of Kerala depends on the prolific monsoon rains for water to drink and grow food. But weak monsoons and recent droughts make water conservation and management vital, so farmers and householders are rediscovering old methods that are yielding new water security. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer reported. (15:47)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Carey Gillam, Alden Meyer, Ramesh Bhushal

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Jenni Doering, Mary McCann, Helen Palmer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. The FDA is under pressure to release apparently alarming test results of weed killer residues in food.

GILLAM: One chemist for the FDA out of Arkansas reported he couldn't find hardly anything that didn't have weed killer in it. Wheat crackers and granola and baby food, oatmeal and honey all contained glyphosate. He said the only thing he found that didn't contain the weed killer was broccoli.

CURWOOD: Implications for our health – also as the monsoons that India needs to grow food become more unreliable, farmers in Kerala are reviving age old water management methods and replanting trees.

SANDHYA: Definitely it’s a part of reforestation, because we follow here rainwater harvesting and rain can happen only if there is forest. We are taking so many things from the nature, so we should give something back to them.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

FDA Scientist Finds Weed Killer on Many Foods

Glyphosate is a common ingredient in chemical herbicides and widely used in commercial agriculture. (Photo: Jeff Vanuga / NRCS)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Back in 2015 the cancer agency of the World Health Organization listed the widely used herbicide glyphosate as a “probable carcinogen.” But in December of 2017 the EPA under Scott Pruitt found no evidence that glyphosate is a human carcinogen and approved its continued use on both genetically engineered and non-GM crops.

That hasn’t reassured many in the public—California is battling in the courts to put a warning label on foods that contain traces of glyphosate, which is often sprayed on wheat, barley and oats to kill them right at harvest to save time for farmers and make those crops dry more evenly. Some 80,000 or more tons of glyphosate is used yearly in America. So in 2016 the Food and Drug Administration began testing for the chemical in foods but has yet to issue a public report.

Curious to learn what the FDA did find about glyphosate residues, journalist Carey Gillam issued a Freedom of Information Act request to see the test results, and wrote about it for the Guardian. Carey Gillam, tell me, what did your FOIA request uncover?

GILLAM: These internal e-mails that I've recently reported show that one chemist for the FDA out of Arkansas reported he couldn't find hardly anything that didn't have weed killer in it. He reported bringing food from home, wheat crackers and granola and things and it all contained glyphosate. He said The only thing he found that didn't contain the weed killer was broccoli.

CURWOOD: Now a few years ago, 2015, the EPA put a list of the most common produce and the amount of glyphosate that's applied to these items in the course of growing them. We'll have a link to that list on our website, but talk to me about some of the foods that got the largest and the smallest amounts of chemicals containing glyphosate put on them.

Corn is grown with roughly 63,500,000 pounds of glyphosate annually, second only to soybeans. (Photo: Fishhawk, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

GILLAM: Well, it's really hard to know for sure if you're relying on government data because our government USDA and FDA routinely have skipped testing for glyphosate. They are charged annually with looking at thousands of food samples for residues of insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, and as I said, they routinely have skipped looking for glyphosate. What we've seen is that a number of consumer groups and academics and others have had to do their own testing to try to find out how much of this weed killer is in our food, and they're finding it in everything from you know, the wine that you're drinking with dinner to snacks and cereals and crackers and cookies that we give our kids in their lunch boxes. Really, that it is this pervasive and we have found from the limited FDA evidence so far, found it in oatmeal, you know baby food oatmeal and honey. Glyphosate is also used in conjunction with avocados and with spinach and things like that. It's dozens and dozens and dozens, more than 70 different popular food crops that are grown with the use of glyphosate.

CURWOOD: Carey, the internal FDA e-mails that you obtained through the Freedom of Information Act revealed that at least one chemist found exceptionally high levels of glyphosate is a sample of corn, but didn't report it outside the agency. Talk to me about that please.

GILLAM: Yeah, so there are these legal limits. We refer to them as MRLs, maximum residue limits or maximum residue levels, and these are the legal limits set by the EPA for how much of a particular pesticide can legally be in a particular type of food, and for corn it's 5.0 parts per million and this scientist reported finding it at 6.5 parts per million, much higher than the legal limit. And what we saw in the internal e-mail was that his supervisor was reassuring the EPA that they would not need to take action on that, that they would simply not consider that to be an official sample - in essence they could ignore it - and we've seen a bit of a pattern of this. The same scientist was the one who earlier had found glyphosate levels at very high levels, levels that should be considered illegal in honey, and again, his supervisors were essentially telling him not to worry about it, that it essentially would go away, they weren’t going to focus on it. It wasn't going to be considered official in any reference.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, they have found levels that aren't legal...why not report them? What's the motivation of the supervisor saying that you don't have to tell other agencies about this?

GILLAM: This has been my frustration in dealing with and investigating the FDA actions on testing for a number of years. They really have been reluctant to discuss this with the public, to release information to the public, to be accountable in any way to the public on this lack of testing, this lack of information. They came under great criticism from the Government Accountability Office in 2014, specifically because they were skipping testing for glyphosate, this very widely used chemical that we know is in our food and in our water. We know it's also in our body. But the FDA has been reluctant to be forthcoming with information. Now they say they will release some data in their next report which should be out at the end of this year or early 2019.

CURWOOD: So, what you're telling me is that basically every one of us living in the United States has likely consumed glyphosate residue in our food. What are the health concerns with that?

Nearly every item of produce commercially grown in the United States is cultivated with the use of glyphosate. (Photo: Rusty Clark, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

GILLAM: And it would be great to know more about that too right? Without having a lot of data, without having bio-monitoring, without being able to correlate intake, dietary intake of this weed killer with any particular human health impacts, it's anyone's guess. Now, there's certainly a body of research out there showing that glyphosate has an array of human health harms. Different scientists have found it tied to kidney problems, liver problems, reproductive concerns, and of course the International Agency for Research on Cancer tied it to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma type of cancer.

CURWOOD: So, it's classified as a probable carcinogen by that agency if I understand it?

GILLAM: That agency, an independent group of cancer scientists classified it as a probable human carcinogen based upon an examination of toxicology and epidemiology research.

CURWOOD: Now, as part of your Freedom of Information Act request, you also found some information about the toxicity of products containing glyphosate, that is formulated products as opposed to simply straight glyphosate on its own. Tell me about that please.

GILLAM: Formulated products, something you would buy on the shelf at your lawn and garden store for instance, those really have not undergone extensive toxicity testing by our government. The testing that they have required has been focused only on glyphosate by itself, which is the active ingredient but not on the formulations and the mixtures of glyphosate with other ingredients. So, it's only now that our national toxicology program is actually doing that testing, and what I've been able to find out and recently reported was that they are finding, of course, that these formulated products are much more toxic than glyphosate by itself. That they are killing human cells much more potent than what has been studied for the last 40 years, that the government itself has said they don't even know what's in these formulations because they’re trade secrets. The companies keep that information pretty close to the vest.

CURWOOD: In other words, the trade secrets are more important than public health.

GILLAM: That's where we are today it seems, yes.

CURWOOD: I mean this all seems rather overwhelming. Glyphosate is so common I don't know how one avoids it. And then there's a question of it being mixed with other ingredients and yet we still don't have a firm grasp on what the potential health effects of long term exposure might be. What advice do you have somebody who is listening to us right now and is concerned?

GILLAM: You know, I think if you're concerned about it, you do your best to educate yourself and to communicate your concerns to your representatives both on a local level and a federal level and to your neighbors, and do the best you can to protect your health and to protect the health of the environment, and what I try to do for instance is I try to buy organic if possible. If I’m feeding my boys fresh berries in the morning, I don't want conventional strawberries because FDA data shows us there are at least 20 different pesticides commonly found in a bowl of strawberries. So, I'm going to go organic. I'm going to go for the least processed, the least pesticide-laden foods that I can.

CURWOOD: A story by Carey Gillam on the presence glyphosate in the food supply recently ran in The Guardian. Carey, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

GILLAM: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: In response to our request for comment FDA Press Officer Peter Cassell emailed:

“Preliminary results for samples collected under the 2016 special assignment showed no pesticide residue violations for glyphosate in any of the four commodities tested (soybeans, corn, milk, and eggs).”

CURWOOD: His full statement is posted at our website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- The Guardian: “Weedkiller found in granola and crackers, internal FDA emails show”

- EPA List of Estimated Glyphosate Usage on Common Crops

- FDA Statement on Glyphosate Testing in Food Products

- The Organic and Non-GMO Report: Why are farmers spraying glyphosate on their crops right before harvest?

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck & the Flecktones, “Flight Of the Cosmic Hippo” on Flight Of the Cosmic Hippo, by Bela Fleck/Howard Levy/Victor Wooten/Roy Wooten, Warner Bros]

Beyond the Headlines

The popularity of pork in China has led to the development of hog high rises, which can hold up to a thousand hogs per floor. (Photo: Suzanne Tucker, Unsplash, creative commons)

CURWOOD: Time to look Beyond the Headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter is with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and DailyClimate.org, where there are all kinds of stories whizzing by. What do you have today for us Peter, what’s going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. You know hogs are a big deal here in the U.S. Anybody who eats meat tends to love things like bacon and sausage, but they’re even a bigger deal in China. And one of the things that’s been a problem is building hog farms close to the population centers in China.

CURWOOD: So, what’s the solution?

DYKSTRA: Here’s something they’re trying as a solution although it certainly raises a lot of questions; hog hotels, hog high rises. They’re building hog farms a thousand hogs per floor, as high as seven floors. And there are plans in the works for a thirteen-story hog high rise.

CURWOOD: Hogs put out a lot of manure, what are they going to do with that?

DYKSTRA: I don’t know, you can’t really build a thirteen-story hog waste lagoon.

[CURWOOD LAUGHS]

Salinas Valley, an important agricultural area in California, is being threatened by saltwater intrusion due to illegal well-drilling in Monterey Bay. (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

The sewage system maybe? Well we don’t know, we certainly know that hog farms, no matter how they’re laid out, are concerns for pollution, for disease with the tightly confined hog populations. And also, just for the smell, I don’t know how that’s going to work in a big city.

CURWOOD: Oh, sounds like a rather ugly pork barrel-type scheme, doesn’t it?

DYKSTRA: Yea.

CURWOOD: Hey, what else do you have for us?

DYKSTRA: Next we’re going to talk about salt water intrusion. It’s a big deal in places like Southeast Asia, West Africa, it’s a concern here in the Southeastern U.S. As fresh water is drawn up for agriculture and for drinking water, and it tends to suck the salt water in, particularly where there’s sandy soil. The Salinas Valley is the latest concern for that, in California, a huge agricultural area.

CURWOOD: Well wait a second, Salinas isn’t right on the ocean. Why is there a concern there?

DYKSTRA: It’s as much as 30 miles away from Monterey Bay and its huge for cash crops like artichokes as well as lettuce. But Monterey Bay, because of illegal wells being drilled in the Salinas Valley for agriculture, Monterey Bay’s salt water is beginning to get into the water supply and once you have an aquifer contaminated by salt water, it becomes pretty much useless for drinking water or for agriculture.

CURWOOD: Oh yea, so that aquifer is right up to the coast itself. That’s hard to reverse isn’t it?

DYKSTRA: Almost impossible.

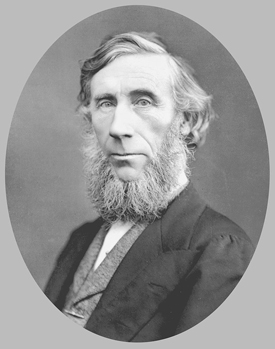

A portrait of John Tyndall, the first scientist to observe what is now known as the “heat island effect,” in which cities are usually warmer than surrounding areas. (Photo: Getty Images, Wikimedia commons public domain)

CURWOOD: So, what do you have from the history vault for us today?

DYKSTRA: Let’s go back to May 18, 1859. A man of many talents named John Tyndall, he was a physicist, he was a surveyor, and mountaineer and he was the first to note that CO2, water vapor and ozone can tend to hold heat into the earth, one of the earliest manifestations of what we now know as the greenhouse effect.

CURWOOD: Uh oh, an early sign of global warming more than a hundred years ago. What else did this scientist discover?

DYKSTRA: He speculated on London as a heat island. This huge city, surrounded by British countryside, always tended to be a few degrees warmer than that countryside. And that was one of the first times we began to observe that as well.

CURWOOD: So how respected was he with these observations or did people deny them?

DYKSTRA: He was a great communicator. He was sort of the Carl Sagan or the Neil deGrasse Tyson of his day. He popularized science, but something that I’m guessing didn’t happen, unlike climate scientists today, he didn’t have climate deniers accusing him of only being in it for the money.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Ok. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and DailyClimate.org. Hey thanks for bringing home the bacon, Peter.

DYKSTRA: [LAUGHS] Alright thanks a lot Steve, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Reuters: “China’s multi-story hog hotels elevate industrial farms to new levels”

- News Deeply: “Seawater intrusion threatens some of California’s richest farmland”

- NASA: About John Tyndall

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck & the Flecktones, “Flight Of the Cosmic Hippo” on Flight Of the Cosmic Hippo, by Bela Fleck/Howard Levy/Victor Wooten/Roy Wooten, Warner Bros.]

CURWOOD: The world gears up to keep fighting for climate protection.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Bela Fleck & the Flecktones, “Flight Of the Cosmic Hippo” on Flight Of the Cosmic Hippo, by Bela Fleck/Howard Levy/Victor Wooten/Roy Wooten, Warner Bros.]

Cool Fix for a Hot Planet: Storing CO2 in Rocks

Lava flows out from Hawaii’s Kilauea Volcano. When it cools, what was molten lava becomes hard, black basalt. (Photo: Sathish J, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Coming up, fighting for the wetland habitat of the tigers of Nepal, but first, this Cool Fix for a Hot Planet from Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

[MUSIC: COOL FIX THEME]

[SOUNDS OF LAVA]

DOERING: The snap, crackle, pop of hot lava flowing from Hawaii’s Kilauea Volcano is a reminder that the ground beneath our feet is very much alive. And even lava that cooled long ago into black, bubbly basalt can jump into action to help fight one of humanity’s biggest challenges: rising levels of carbon dioxide.

Basalt has the chemical potential to help take up carbon, as does peridotite, a greenish-black rock formed when magma cools deep in Earth’s mantle. If you happen to have an August birthday, peridot, its glassy, olive green cousin, is your birthstone. Basalt and peridotite aren’t gemstones, but they show their special powers when they come into contact with carbon dioxide.

If the CO2 is dissolved in water, as in a fizzy soda –

[SOUNDS OF SODA CAN OPENING, FIZZING SFX]

Vesicles (the geological term for bubbles) in basalt from Hawaii’s Kilauea Volcano. (Photo: James St. John, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

-- the chemical reaction happens fast. Magnesium or calcium ions in the rock lock up the carbon dioxide as a solid carbonate, like chalk, or the Tums or Alka-Seltzer you might pop in your mouth after a rich meal. Earth scientist Juerg Matter led a pilot study that injected carbon dioxide deep into Iceland’s basalt, with promising results.

MATTER: So if you go to the scientific literature, if you look at laboratory experimental data, and if you look at what the perception of scientists was, how fast mineralization occurs – it takes, you know, hundreds of years to thousands of years. And what we showed in this project was that within less than 2 years, all our CO2 we injected was mineralized.

DOERING: That project is now expanding, with support from several European research institutes. How feasible this method of capturing and storing carbon is, and what it would cost, are still uncertain, but basalt is common. It covers large areas of India, the Pacific Northwest, and Iceland. In all, basalt covers more of the Earth’s surface than any other rock type on this third rock from the sun. So in a twist of fate, ancient hot lava might just help our world chill out.

[SOUNDS OF BUBBLING LAVA]

That’s this week’s Cool Fix for a Hot Planet. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And if you have an idea for a Cool Fix for our hot planet, please send it our way and we might put it on the air. Our email address is: comments@loe.org –

That’s comments@ loe dot org.

Related links:

- The CarbFix project in Iceland

- Columbia’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory: about using mineral carbonation in peridotite for CO2 capture and storage (CCS)

- NYTimes Interactive: “How Oman’s Rocks Could Help Save the Planet”

[MUSIC: COOL FIX THEME]

UN Climate Talks Gear Up for December

The latest UN climate negotiations in Bonn concluded on May 10th, 2018. (Photo: UNFCCC)

CURWOOD: Here’s another cool fix for a hot planet, the UN climate treaty. In December its 190 or so nations will come together in the coal country of Poland to try to move ahead with ‘rules of the road’ to implement the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015. And before December there are a series of meetings intended to iron out any obstacles and disagreements that could derail progress. Two weeks of those sessions just wrapped up in Bonn, Germany, and as usual, Alden Meyer of the Union of Concerned Scientists was there. Welcome back to the program Alden!

MEYER: Thanks, Steve. Good to be with you again.

CURWOOD: So, the latest round of climate talks wrapped up in Bonn recently. What was the mood?

MEYER: The mood was workman-like. They were trying to reach agreement where they could on particular issues, but they also acknowledged, I think, that they're behind schedule and that's why they've scheduled an extra week of negotiations in Bangkok, Thailand, in early September to try to get through that part of the negotiation process before the annual climate summit in Poland this December.

CURWOOD: So, what's the ultimate goal, really?

A scene from the opening of the Talanoa Dialogue Initiative at last year’s Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC led by Fiji in Bonn. (Photo: Climate Alliance Org, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

MEYER: Well, there's several goals for this year's climate summit. The most prominent is to reach an agreement on what's called the Paris Agreement Work Program, which is a whole range of issues relating to implementation of the historic agreement reached in Paris three years ago. So, things like what kind of information should countries provide on their so-called nationally determined contributions, which is the commitments they're making under Paris. What kind of information should countries provide on how well they're doing on meeting the commitments? And how do you get ready to ratchet up ambition of the commitments the countries have already made as everyone acknowledges is needed to meet the temperature limitation goals in Paris?

CURWOOD: So, what needed to be done at this session, before the big session, and what in fact did get done?

MEYER: Well, they needed to try to work out draft negotiating text on the Paris rulebook. They made progress in some areas such as compliance and these global stock take of ambition that’s scheduled for 2023. But they really came to loggerheads on the issue of what kind of information countries should provide on their nationally determined contributions and should that be differentiated between developed and developing countries. Or should it be differentiated on the basis of the kind of commitments that countries are making? And of course you'll remember that the US historically and other developed countries as well have had a real opposition to the so-called firewall where developed countries have one form of commitment and developing countries have another. That's one of the reasons why the Kyoto Protocol from 1997 kind of broke down, and so when India, China, and some of the other developing countries tried to reintroduce the notion of this firewall, it produced a strong reaction from the developed countries and they really came to gridlock on that.

CURWOOD: So, the big annual meeting will be right in the heart of coal country there in Poland in Katowice, the third time the conference of the parties has come to Poland. How does that affect these negotiations?

MEYER: Well, the real question is can Poland, the presidency of Poland, separate itself from the domestic interests of Poland, because as you know, Poland has been resisting efforts within the European Union to increase ambition. They have been fiercely defending their continued use of coal domestically, but as the president of the conference of the parties, you need to rise above your national position and try to facilitate agreement on behalf of all the countries attending and I think that's the open question people have.

CURWOOD: So, of course, the US has said it wants to get out of the Paris Climate Agreement - which it can't until 2020 - but in the meantime what has that done to the process?

MEYER: Well, no one is ratcheting down their commitments. We haven't seen a single country follow President Trump in saying they want to get out of the Paris Agreement. We haven't seen a single country saying they're not going to try to meet their commitments they made. Of course, the proof will come a couple of years down the road when it comes time for countries to finally put forward their longer term targets. So, the real question is, “Will countries do more?” The good news is, I think, countries are increasingly aware of the growing number of mayors and governors and business leaders and others in the states that are part of the so-called "we are still in" movement which is saying no matter what President Trump does, we're going to do our best to meet the US commitments under Paris. And they're also aware, as you said, that President Trump can't formally withdraw until ironically one day after the next presidential election in November of 2020.

Alden Meyer is director of strategy and policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists. (Photo: Union of Concerned Scientists)

CURWOOD: So, what role did the US play at these most recent climate talks given Mr. Trump's commitment to get out of the process?

MEYER: Well, they were still very active in the technical negotiations; behind the scenes, for example, the United States co-chaired with China the negotiating working group on transparency and reporting requirements. So, they were very active on that front. They obviously could not be helpful in the finance discussions, and there was a fair amount of anger from, particularly developing countries, to some of the positions the US was taking.

CURWOOD: By the way I understood that the US took a little bit of heat at the session in Bonn because President Trump had promised to say what he didn't like about the Agreement, and so far he actually hasn't said anything formally to the Paris Climate Agreement negotiators.

MEYER: Well, that's right you remember last June when he made his Rose Garden speech announcing his intention to withdraw, he said that was subject to whether we could negotiate a better deal, and of course, you're right that in the time since then he has not made clear what such a better deal would look like. And so I think that just showed that he really didn't understand what the Paris Agreement was, how it had been negotiated, how flexible it really was. And he was just expressing disagreement with it primarily because he thought it was too stringent on the United States and because frankly, President Obama was the one that helped drive it through.

CURWOOD: Now, which countries have emerged with the vacuum that the US has left behind?

MEYER: Well, it varies on issues, but I mean, obviously China has been stepping up its engagement. They have a bit of a mixed bag though. They are doing a lot domestically to shut down some of their older coal plants and ramp up investments in renewable energy and efficiency but at the same time they are financing a lot of coal plant expansions across Southeast Asia. The European Union is trying to step up, but of course they have to get agreement among 28 member states which makes it difficult, and there's no kind of dual pillar like there was between the United States and China driving the Paris Agreement through to completion as we saw under President Obama, President Xi back in 2014, 2015. That sort of international leadership has not come together yet, and I think that's one of the real challenges.

CURWOOD: To be blunt, sometimes when you mention these climate negotiations, the response is a big yawn. “Oh, those aren't doing anything, why is this a news story.” What do you say?

MEYER: Well, I can see that point of view, how it's frustrating to people watching the slow pace in these negotiations, but I would say that Paris three years ago was a breakthrough in the sense that you had unprecedented number of countries engaging in this process domestically, bringing stakeholders together - business, labor, others - seeing what they could do. Of course some did a better job of that than others, but you've achieved a kind of universal engagement on this process and now we have to get it right. We have to mobilize climate finance in a transformational way, going beyond just the public finance to really affecting the trillions of dollars that are in play in the private sector. There's still work to do, but I think you can show how in many cases these negotiations have led to real changes on the ground in countries. It's just not far enough and fast enough, I think that's the frustration that's very legitimate.

CURWOOD: Alden Meyer is Director of Strategy and Policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Alden, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MEYER: It was good to talk to you, Steve.

Related links:

- A UNFCCC press release about the outcome of Bonn

- Alden’s last update for LOE on the progress since the Paris Agreement

- Alden Meyer UCS Profile

[MUSIC - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

BirdNote®: Dippers on the Elwha

An American Dipper holds a salmon egg in its beak. (Photo: © Tony Mitra)

CURWOOD: Fresh water is a precious commodity that we divert and try to control.

But sometimes, we reverse those constraints and let water run free – and that can bring a flood of support for wildlife. Here’s Mary McCann with today’s BirdNote

MCCANN: In 2014, on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State, the dams on the Elwha River were removed. It was the largest removal of its kind in history. As the river ran free again, salmon from the Pacific were able to spawn upstream for the first time in 100 years – having a dramatic impact on American Dippers - lively little riverside birds.

[Song of American Dipper]

Biologists with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, and Ohio State University drew small samples of blood from dippers that they then released unharmed. Analysis of blood and feathers show that birds with access to salmon have higher survival rates and the females have better body condition than those with no access to the fish. These dippers are also much more likely to stay on their home territories, rather than expend energy to forage widely. And they are 20 times more likely to attempt raising two broods in a season, the most important contributor to population growth.

So nutrients from spawned-out salmon and salmon eggs are giving the river’s ecosystem new vitality.

I’m Mary McCann.

[Song of American Dipper]

This American Dipper dives in for a meal. (Photo: © Mike Hamilton)

Written by Todd Peterson

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. American Dipper [8992] recorded by R S Little

River ambience recorded by Chris Peterson. ‘Stream, Moderate’ Track 18 Nature SFX recorded by Gordon Hempton at http://www.quietplanet.com

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2005-2018 Tune In to Nature.org May 2018 Narrator: Mary McCann

http://birdnote.org/show/dippers-elwha

CURWOOD: For some photos – dip into our website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- This story on the BirdNote® website

- The American Dipper research project

- Learn more about the Elwha River restoration

[MUSIC: Bruce Daniels, original composition inspired by Benny Max, not commercially available. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uurnt29Rp2k]

Nepal’s Threatened Wetlands

Local women fish in Ghodaghodi Lake, an area home to roughly 16% of all the birds in Nepal. (Photo: Ramesh Bhushal / The Third Pole)

CURWOOD: For many people, Nepal conjures up images of the snowcapped Himalayas, with Anapurna, K2 and Everest, the tallest mountain in the world.

Those icy mountains make Nepal water rich – with 6000 rivers and hundreds of lakes, in a country that’s roughly the same size as Iowa. Roughly 5 percent of Nepal’s land is covered with marshes and other wetlands, critical habitats for endangered species and migrating birds. And even though Nepal signed the Ramsar Convention to preserve wetlands, Ramesh Bhushal, the Nepal editor for the South Asian online magazine The Third Pole reports the government is doing little to protect these vital areas. He’s on the line now – Ramesh, welcome to Living on Earth.

BHUSHAL: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, you recently wrote in an article in The Third Pole that wetlands are facing a lot of threats. What are the points of concern?

BHUSHAL: The first thing is that people don't understand the value of wetlands. A lot of people think that it is waste land, just waste. There is no reason to conserve or protect and people try to increase those areas. For example, schools are built or hospitals are built and governments also are not serious about protecting them. Their value has not been understood well by the communities, by the government, by the authorities. That is where the problem starts.

CURWOOD: So, I understand that the Ramsar Convention would protect the wetlands, but you're telling me that the government doesn't pay a whole lot of attention to that.

BHUSHAL: In papers there are wetlands which they have designated those wetlands as the wetlands of international importance, but only a declaration doesn't make any differences. You have to invest on it, you have to mobilize the community, and you have to have a kind of a management plan. You have to invest your time and resources. So, they have declared it - to be honest it is, but there hasn't been much more focus on their protection.

CURWOOD: Tell me about some of the species that depend on the wetlands for habitat and for their drinking water.

BHUSHAL: There are numerous wild animals which rely on the wetlands. For example, Nepal is one of the hottest spots for the migratory birds. So, birds travel all the way from Siberia and across the Himalayas and go to the southern plains of Nepal and even to India. So, those birds fly for thousands of miles and then stay for a few months in Nepal's wetlands, and then return back after a few months. Kind of a winter vacation, for example.

And Nepal is home to one of the world's endangered species called One-Horned rhinos. It is called Rhinoceros unicornis, and it is one of the largest populations is in Nepal. They depend on wetlands for drinking water. If you talk about the tigers, there are only 4,000 tigers in all of the world, Royal Bengal tigers, and Nepal has about 200. And these tigers also depend on those wetlands for drinking water or for other purposes.

CURWOOD: So, I understand that wetlands have a large cultural value in Nepal. Tell me about that please.

BHUSHAL: Most of the water bodies are near the villages. They worship God in those kind of wetlands. They go there to do rituals in Hindu culture. There's open cremation, so when somebody is dead, they take that dead body to that riverside on the bank of the river and then they burn it. Once you burn those dead bodies, it will flow down to the Ganges where they call it the holy river, then you are on the way to heaven. So, water is very important even after your death.

CURWOOD: So, Ramesh, what's the outlook for these wetlands. What do you see as the future for the wetlands of Nepal?

BHUSHAL: They are in sorry state to be honest, and if we don't protect them, they won't survive for long. It's for sure, because the area is decreasing, there are a lot of threats already. There and lot of people are saying that the rainfall pattern will change due to climate change and if rainfall pattern changes, then those wetlands may not get enough water to store. So, there's the threat of the climate change in the years to come as well as the human threat that has been place for long and it is still continuing. I'm hopeful that more efforts will be applied, but if you don't do it now then it will be too late.

CURWOOD: Ramesh Bhushal is the South Asia content coordinator for the Earth Journalism network and Nepal editor for the South Asian online magazine "The Third Pole". Ramesh, thanks so much for taking the time today.

BHUSHAL: Thank you.

Related links:

- The Third Pole: “Nepal’s fertile but forgotten wetlands”

- Explore Nepal’s wetlands with an interactive map

[MUSIC: Carolyn McDade & Friends, “Ocarina Improv” on As We So Love, not commercially available, self-published.]

CURWOOD: Coming up, from water problems north of India to water worries farther south, That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Elaine LaZizza Cronin, “The Water Is Wide,” Folk Salad, Traditional American, Off the Record]

Saving Kerala's Fresh Water

Mangroves in Kerala, India help prevent erosion, blunt the force of storms and provide habitat for white ibises and other creatures. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. In South Asia, the monsoons are the key to growing and irrigating crops, and filling wells with drinking water.

Some South Indian states, like Kerala, typically get strong monsoons – as much as ten feet of rain usually falls there every year. But in the last decade the monsoons have become erratic, and there have been some severe droughts - perhaps due to the changing climate and shifting wind patterns. This has led Kerala’s government to declare water conservation a top goal. And as Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer discovered on a visit, reports of the monsoon status can lead the local news.

Vargheese Tharakan has dug trenches across his steep hillside plot to retain water for his banana plants. Every 4 or 5 feet along the trench an earthen mound keeps water near the roots. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

[SOUND OF RAIN]

NEWS READER: The Monsoon has finally reached mainland India, with 2 consecutive days of rain in Kerala. But so far it’s been a weak monsoon that missed its expected arrival date and arrived 5 days late, amid fears of drought-like conditions, and an intense heat wave.

[SOUNDS OF WALKING, BIRDS, DISTANT ROOSTERS CROWING]

PALMER: Weak unreliable rains can be a disaster for farmers, but on his plantation in Thrissur where I meet him and his family shortly before the monsoon arrives, Vargheese [vur-gaze] Tharakan has dug trenches across his steep hillside plot to corral the water. Vargheese is tall and broad, in a spotless white shirt and dhoty, the broad length of cotton cloth many Indians wear knotted round the waist. His petite wife Sandhya and children wear western clothes, jeans for 10 year old Varsha and 6 year old Varun and a gray sweater, black pants and big sunglasses for Sandhya. She points up the slope to rows of banana plants, with broad glossy leaves, heavy with green fruit.

SANDHYA: It’s basically a drought affected area, and even though in Kerala we get 3070 mm rain, but here we get much lesser. As you can see it’s a slope kind of geographical pattern, so he has done cross trenching method and each and every drop of water which falls here is trapped and forced under the ground.

PALMER: It’s partly a very old technique to retain rainwater on this steep three and a half acres. Now the slope is lush, with a tangle of grass and creepers among banana plants, and between each row, a trench about two feet deep. Every 4 to 5 feet along the trench, there’s an earthen mound – effectively creating a series of individual water storage pools – though they’re dry now, between the monsoons.

Vargheese Tharakan proudly shows the fruits of his healthy banana trees. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

SANDHYA: And you can see that we have a pond kind of thing here – during this season – like November, December, January and all, it is kind of winter and windy and all. So usually what happens is all the water sources dries up, but you can see it is filled with water still – and we are not watering the plants with any kind of agriculture methods. All these bananas they are standing here, they’re giving fruits entirely on the rain water he has harvested and stored under the earth.

PALMER: We walk over to the pond – it’s deep with near vertical earthen sides and a frog swimming in its murky green water. It’s not only Tharakhan’s own bananas that benefit from this water retention. Rainwater management expert Jos Raphael has watched this farm’s development closely. Jos is serious and intense and like many professional men I met in Kerala, he has a bushy moustache. Holding back the water like this, he says, solves a problem for the community at the bottom of the hill as well.

RAPHAEL: Thirty farmers living in the downhill, they’ve got 10 acres of land together – so these farmers, they had water scarcity for irrigation and for the drinking and the domestic water requirements. Then the government gave a tube well, irrigating these 10 acres of land. It worked almost till 2012 – so ultimately what happened, this tube well gone dried.

PALMER: But then, Jos says, Vargheese Tharakan took over the barren hill plantation above their fields, and dug his transverse trenches that hold back the monsoon rains so they percolate slowly through the earth.

Vargheese Tharakan has planted baby coconut palms on top of the some of the trenches he built. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

RAPHAEL: And this barren hill, he made it as a garden, then the rainwater harvesting with these contour trenches helped the people in the down hill; otherwise this rainwater used to flow down and ultimately to reach the paddy fields and go to the sea, Arabian Sea.

PALMER: We head down the hill to check out the wells of the village at the bottom – and there’s water in their depths as well – and clothes drying on the washing lines by the brightly painted houses.

[TRAFFIC SOUNDS, CAR DOOR SLAMS AND CROWS CALLING]

From the village, Jos Raphael takes me to his home, a simple bungalow where he shows off rainwater conservation for the household. It’s a system of gutters and PVC pipes that feed the well in his garden with a motor to pump water up to the large blue rooftop tank. He says people all used to collect rainwater, much as people round the world do now in barrels for their gardens, but increasing development and urbanization made it obsolete.

A village well and pulley system for drawing water (Photo: Helen Palmer)

[QUIET OUTDOOR ATMOS, OCCASIONAL BIRDS, WALKING, FROM BIRDS, DISTANT MUSIC]

RAPHAEL: Well in the past history of India, India used to collect rainwater for the domestic use, then what happened, the shift took place in the 1950s, this modernization and piped supply and dams and canal irrigation system. When the people start to get the water in the homesteads, with the piped water supply systems, the people tend to ignore their homestead wells, so the traditional wisdom of harvesting rainwater within the homestead the people tend to forget.

PALMER: And the neglect of the old ways, so now the rainwater just runs off to the sea, isn’t the only water headache for local officials. Deforestation in the once thickly wooded mountainous Western Ghats has reduced the amount of water these western highlands retain, and increased erosion. But Jos Raphael works for a non-profit that got busy.

RAPHAEL: We’ve got a project in Thrissur district administration called Mazhapolima, that means “the bountiful rain”, so we are trying to harvest this rainwater as well as we promote the homestead watershed approaches so that the rainwater in the homestead is conserved.

Jos Raphael’s water collection and storage system at his home. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

[SCHOOL – CHATTER OF CHILDREN]

PALMER: We visit one of his projects at a public government high school, where Jos Raphael, smartly dressed in a well pressed green cotton shirt and grey slacks is greeted warmly. His team supplied equipment to collect that bountiful rain for the school. Mini Kollat, a no-nonsense economics teacher in black with a striking geometrically patterned black and white scarf, explains.

KOLLAT: The roof’s water will be collected by the pipes and it will be collected to the wells, to the filter, so that will increase the level of ground water. Water is an elixir of life, because there is no option to water.

PALMER: Mini Kollat’s students helped to put up the gutters and connect the pipes that funnel the water through charcoal filters into the huge well in the school courtyard. That well now supplies all the basic needs of the school. And 18 year old Fabien, tall and gangly in his school uniform check shirt and blue pants, tells me the pupils helped the community around the school as well.

Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer with Jos Raphael, a rainwater conservation expert with the nonprofit Mazhapolima. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

FABIEN: That Mazhapolima scheme was to reduce scarcity of water in that area. In our area there are a lot of poor people so by connecting the pipes, and by using the filter and the motor etc we can give water.

PALMER: Fabien tells me the NGO supplied gutters and pipes and the students helped set them up for their own parents and on the roofs of many manual laborers who live round the school, who don’t have the cash to buy their own system. Jos Raphael says he’s proud of Mazhapolima’s success.

[QUIET OUTDOOR SOUNDS, DISTANT BIRDS AND CRICKETS]

RAPHAEL: We have done more than 25,000 well recharging units in Kerala and with this government subsidy, that will help the people to help recharge their homestead wells, so it has become a role model across the state – so that’s the success of this piloting in Thrissur district. That’s what I’m happy about.

PALMER: But if some townsfolk need a refresher course in traditional methods of managing water, those ways are still widely practiced in the countryside by farmers like Giresha at Wadhikhancheri village, a short drive from the High School down on to the low-lying coastal plain.

[SOUND OF CAR DOOR, CHICKENS CLUCKING, DOGS BARKING]

Giresha keeps milk cows and grows rice [shown here] and coconuts at his organic farm at Wadhikhancheri village. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

The guard dogs greet us boisterously at Giresha’s farm. He cultivates six acres of rice and coconuts organically on land his father and grandfather farmed before him. Beside the cowshed, with its dozen indigenous milk cows, Giresha points to a special breed of chicken pecking about in the farmyard.

GIRESHA: We locally call it karingori. It’s completely black – see? everything is black and even the meat is black.

PALMER: Really? Gosh, black chicken!

GIRESHA: And even the bones, internal organs, even the blood.

[HENS CLUCKING]

PALMER: Giresha tells me it’s important to him to preserve these heritage breeds – the chickens as well as the cows. We cross the yard to the cowshed, where one of his workers is hosing down the floor, and he tells me that water drains down to his organic paddy fields – which provide not only rice, but also hay for the cows.

The rice in Giresha’s fields is a brilliant green even during Kerala’s dry season. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

GIRESHA: I feed hay – mainly hay because I got a paddy field, so the hay is here.

PALMER: So basically you get the hay, the rice straw from the paddy field and you feed that to the cow?

GIRESHA: And the cow dung as a fertilizer I am using back to the fields, so I don’t have to purchase fertilizers.

PALMER: As well as the runoff from the cowshed, Giresha uses rainwater during the dry season for irrigation. Some of his fields lie below sea level, he says, and in monsoon season they flood and he can harvest fish. He says it’s vital to maintain the level of fresh water in the paddy to feed the local aquifers and hold back the salt.

[TRAFFIC NOISE AND WATER LAPPING AT COAST]

Rising sea levels are also increasing salinity in fresh water at the coast and percolating into drinking water wells there. On top of that, increasing development, especially for tourism, has led to widespread destruction of one of the main protectors of Kerala’s coastline, the mangrove swamps. That’s a big worry for Ravi Panakhal – whom I meet about five miles from Giresha’s farm at an airy barn on muddy flats by the Arabian Sea shore. Here he teaches school kids about the importance of the mangroves.

Giresha feeds his indigenous Indian cows hay from his rice paddy fields, and then fertilizes those fields with the manure the cows produce. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

[SOUND OF WATER LAPPING AT SHORE]

PANAKHAL: There were so many mangrove forests in India but during the course of time people for their selfish interests, own interests, they have removed all the mangroves.

PALMER: Panakhal, a trim retired army colonel, heads the NGO Nature, Environment and Wildlife Society of India that gets the local schools involved in replanting the mangroves. Along a series of muddy trenches filled with brackish water, they’ve set out rows of baby mangrove plants, planning to grow them up until they can be planted along the shore for their many benefits.

PANAKHAL: Mangroves cleans the water; besides it is the habitat of a lot of birds, even the migratory birds also. Besides the biodiversity, there are special species of a lot of plants, animals and such things.

PALMER: As well as cleaning up the water, mangroves help prevent erosion, blunt the force of storms and provide a nursery for baby fish.

PANAKHAL: If we keep the mangroves in the belt of this area, the fishing, because actually these people were making livelihood from the fishes, that will improve and the coastal area will be protected and the water will be purified, not salty water, clean water for drinkable water.

PALMER: Protecting species and conserving clean water are a chief aim of the government’s Green Kerala initiative. What Ravi Panakhal wants is a Nature Reserve to do just that on this swampy parcel of coast.

PANAKHAL: This is 234 acres of land is there. What we want, actually we want a protected area, to protect the livelihood of the people and to serve mankind as well as the existing species. It's land for the government but government is not interested in it.

Brackish water ditches lined with baby mangroves that Ravi Panakhal wants to plant along the shore to fight erosion, help clean the water and act as a nursery for fish. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: Tourist condos and hotels and restaurants bring in cash to undeveloped areas like this and that’s what appeals to the government and local businesses, Panakhal tells me. But still he says, Nature will have the final say.

PANAKHAL: If we can build a building here and get more money, I will get more money, but this area, it is going to be spoiled and the next generation, that will be suffered. They don’t want to think about the nature, if nature loses, we are going to die. The next generation cannot survive without water, without this nature, it’s very very important, we must keep it up!

[CROSSFADE LAPPING WATER TO SOUNDS OF BIRDS AND CRICKETS]

PALMER: Back at his banana farm in the highlands, Vargheese Tharakan and his family are also keeping Nature up by reforesting, which helps bring rain to these dry hills. Some of the plants stand in the shade of native teak trees that also grow here. Sandhya says they’re planting even more, not to harvest, but for their children, Varsha and Varun, and to retain the water, protect the soil and fight global warming.

PALMER: Sandhya, tell me about the teak.

SANDHYA: It was here when we bought this plot actually – and we don’t have any plans to cut it, because it amounts to deforestation. And you can see it's a slope kind of geography here so it has to be here to hold the soil together and prevent soil erosion.

Rubber plantations line the steep hillside where Vergheese Tharakan grows his organic bananas. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: So you are planting more?

SANDHYA: Yeah definitely we plant more and definitely it’s a part of reforestation, because we follow here rainwater harvesting and rain can happen only if there is forest.

PALMER: And is this because the government says you have to reforest, or is it something you want to do?

SANDHYA: No, it’s from our kind of ideology we are doing this. We are taking so many things from the Nature, so we should give something back to them, it’s not always taking, giving also is a part of life.

PALMER: The children, 10 year old Varsha and 6 year old Varun scramble up the steep ditches under the trees, and I scramble after – Varsha tells me she’s already trying to give back to the family.

VARSHA: I wanted to grow many things but I thought about starting off small by growing some bean plants. So I planted them maybe 3 or 4 months ago and now they have grown a lot and now they are giving of beans and we are already plucking a few of them and using it for our curries and all.

Sandhya Tharakan says it’s important to her and her husband Vargheese to reforest their land with teak trees; they help hold the soil together, and she wants to give back to nature. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: So basically you are growing beans that the family can eat?

VARSHA. Yeah.

PALMER: Vargheese, her father smiles at her proudly – he says growing things is

nothing less than the key to the future. He grabs my hand urgently and struggles with English as he tries to get his big idea across, that children everywhere should learn farming.

THARAKAN: Peaceful world. Standard studying agriculture, one subject compulsory all over world – after then – peaceful world.

PALMER: Sandhya helps him out.

SANDHYA: So what he ultimately aims is world peace – through agriculture, through cultivation, through farming.

PALMER: World peace though tending the land - it’s a grand dream, but in their small plot of paradise, the Tharakan family is doing its bit, growing bananas and vegetables, restoring the soil, bringing back the trees and saving the rain.

For Living on Earth, I’m Helen Palmer in Kerala, India.

Related links:

- The Mazhapolima rain conservation project

- The Nature, Environment & Wildlife Society

- Journal article: “Effect of climate change on seasonal monsoon in Asia”

- United Nations webpage on rain harvesting in Kerala

- India Climate Dialogue: “W(h)ither Kerala’s mangroves”

- IndiaTimes blog: “Why India needs protection from unreliable monsoons”

- Listen to our first story in the series: “Kerala’s Ambitious Organic Pledge"

- The second story in the series: “Pesticide Peril in Paradise”

[BIRDSONG]

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q2ZnJiPQ3hM

Vayali Folklore Group, recorded live at the Sahaj Parab, 2015, published by Musiana]

CURWOOD: Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Hannah Loss, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Aynsley O’Neill, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tyger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth