October 31, 2014

Air Date: October 31, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Harsher Winters Related to Arctic Sea Ice Loss

View the page for this story

A new study published in Nature Geoscience found that the likelihood of unusually cold winters in parts of Eurasia doubles as the Arctic warms and sea ice declines. Host Steve Curwood discusses the findings with Rutgers University climate researcher Jennifer Francis, who also explains how rising temperatures in the far north are changing world weather. (08:40)

Declining Oil and Divestment

View the page for this story

In parts of the US, gas prices have dropped below three dollars a gallon. Short term, low oil prices can lead to more driving and more pollution, but as reporter Elizabeth Douglass tells host Steve Curwood, the recent drop in the price of crude could signal long-term problems for the fossil fuel industry, and that’s good news for the divestment movement. (06:15)

Agent Orange-Related Herbicide Approved for GMO Crops; EPA Sued

View the page for this story

A coalition of environmental groups and farmers is suing the EPA over approval of Dow Chemical’s new GMO crop herbicide, Enlist Duo, a combination of glyphosate and 2,4 D, an ingredient of Agent Orange. The lawsuit alleges inadequate environmental and health assessments by the agency. Host Steve Curwood and the Center for Food Safety’s science policy analyst Bill Freese discuss the suit and effects the herbicide might have on weed resistance and pollinators. (08:30)

Fascinating & Toxic - Traditional Moroccan Tanneries

/ Amulya ShankarView the page for this story

Colorful leather goods are popular tourist souvenirs from traditional tanneries in Morocco. But workers must stand in toxic, chromium laden waters every day there to soften and dye the hides, and prolonged chrome exposure and lax disposal of waste tannery water can cause serious health and environmental problems. But as Amulya Shankar reports from Fez, modern tanning techniques can help mitigate these issues and maintain some of the old-world charm. (08:15)

Lead-Free Ammunition Saves Waterfowl

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Migrating waterfowl are often hunted in the fall, and the birds often swallow shotgun pellets that miss. But now, as Mary McCann reports, hunters no longer use toxic lead pellets, which helps protect the health of surviving waterfowl and their ecosystem. (02:15)

Albanian Migratory Bird Poaching

View the page for this story

The marshes of Albania were once a vital feeding ground for migrating birds traveling between North Africa and Europe along the Adriatic Flyway. But as writer Phil McKenna tells host Steve Curwood, since the fall of the country’s communist leaders, an onslaught of poaching has left the skies eerily quiet. (08:15)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, host Steve Curwood and Peter Dykstra discuss a novel way of culling an invasive wetland reed, the cost of China’s disappearing wetlands and Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster. (04:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jennifer Francis, Elizabeth Douglass, Bill Freese, Phil McKenna

REPORTER: Amulya Shankar, Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Record warmth across the globe this year helped melt more sea ice up in the Arctic, and there may not be a way back.

FRANCIS: We've gotten into this vicious cycle that means that the more ice we lose, the more ice we melt, and the warmer it gets in the Arctic, and so we’re in this situation now where it really can’t recover.

CURWOOD: And less ice makes the jet stream more wavy, which can bring colder winters to parts of the northern hemisphere. Also, tourists love to visit Morocco’s traditional tanneries, but the leather workers need to clean up their toxic waste water.

LANGE: The whole idea is to not just to reduce the chrome effluent, but effluent overall and reduce the water usage. Water’s becoming a very expensive commodity, and we know there’s a limited supply.

CURWOOD: We'll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

Harsher Winters Related to Arctic Sea Ice Loss

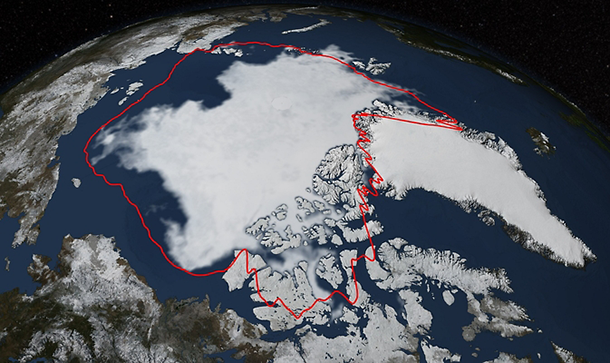

Arctic sea ice hit its annual minimum on Sept. 17, 2014. The red line in this image shows the 1981-2010 average minimum extent. Arctic Sea-ice hits its sixth lowest on record in 2014. Data provided by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency GCOM-W1 satellite. (Photo: NASA/Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. 2014 is on track to be the warmest year on record, but if you think the trend might bring a mild winter, you could be out of luck. A new study from Tokyo indicates that the increased melting of Arctic sea ice is linked to colder winters, at least in parts of Europe, Asia, and North America. Jennifer Francis is a Research Professor at Rutgers University, who was the first to suggest this link between Arctic ice loss and colder winters. So we got her on the line to explain how it all works. Welcome to Living on Earth, Professor Francis.

FRANCIS: Thank you so much for having me.

CURWOOD: We're scratching our heads. The study that was just published says cold winters in Europe and Asia are twice as likely to occur given the decline of sea ice in a particular Arctic area. How could this warming way up north create all this cold in the middle of winter?

FRANCIS: [LAUGHS] You know, the atmosphere's a very complicated thing, and we're really just starting to unravel all of the nuances of how it's changing, how the changes in the atmosphere are related to other changes that we’re seeing the climate system, and one of the most obvious of those is the loss of sea ice in the Arctic. In fact there's only about half as much sea ice coverage in the Arctic now as there was only 30 years ago. It's just been disappearing at an amazing rate. One of those regions where the ice is disappearing the fastest is just north of Scandinavia and western Russia, an area called the Barents-Kara Sea area. What we're learning about this area is that it's very important for the atmosphere.

Scientists have been monitoring ongoing changes in Arctic sea ice for decades. By collecting samples of ice as well as a wide range of satellite-based data to document the changes, scientists find that Arctic sea ice is melting at an increasing rate, with half of disappearing in just thirty years. If the trend continues, Arctic sea ice may be gone by the year 2100. (Photo: courtesy of NOAA Photo Library)

When we lose that ice there, the dark ocean underneath during the summertime absorbs a lot of extra energy from the sun, and so that water warms up a lot more than it used to. When fall comes along and the cold air starts to move in again, all that energy that was absorbed through the summer in that region then gets re-emitted back to the atmosphere and that causes the air above this region to warm up a lot. This has the effect of actually bulging the jetstream northward. The jetstream is this fast-moving river of air high over our heads that generates the weather that we experience down here on the surface, and when it is forced to bulge northward like that it compensates by bulging southward just downstream, which would be to the east. When that happens, it allows the cold air from the Arctic to plunge farther south, and so what we're seeing is; during summers when there's less ice than normal in this Barents-Kara Sea area we're finding the jet stream taking this wavier path with the bulge up north of Scandinavia and then a big dip south over Asia allowing that cold air to plunge southward and creating those colder winters.

Arctic sea ice extent on March 14, 1983 (pictured left). Arctic sea ice reached its annual maximum for 2014 on March 21 (pictured right). According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), Arctic sea ice extent reached 14.91 million square kilometers (5.76 million square miles) on March 21. Extent is defined as the total area in which the sea ice concentration is at least 15 percent. (Photo: NASA)

CURWOOD: Now some people would say, "Look, way before all the Arctic ice started to melt, some winters were very cold and others were mild”. What about natural variability in weather conditions?

FRANCIS: Yes, natural variability is alive and well. The atmosphere is a very chaotic system and that presents challenges for measuring things like how the atmosphere is going to respond to losses of sea ice and that sort of thing so this recent paper that's triggered this discussion went about this using computer models to simulate the response of the atmosphere to the loss of sea ice. And they did this by running a very sophisticated computer climate model 100 times with the same sea ice loss, and because of natural variability every one of those computer runs looks a little bit different from each other. By doing it 100 times, which is something of course we can't do with the real world, they were able to generate statistics that showed that these cold...extra cold winters in Asia were twice as likely to occur when they put reduced sea ice in this Barents- Kara Sea area as compared to when there was lots of ice in that area. So this is one of the tools we can use to try to get a better handle on how different changes in the climate system are going to affect things like weather patterns.

Bright white ice reflects sunlight from the Earth’s surface. In contrast, open water is dark, and absorbs sunlight. As sea ice melts, more water is exposed, which traps more heat. (Photo: NOAA Photo Library)

CURWOOD: So, this past winter we heard a lot about the polar vortex...a synonym for a wavy jetstream?

FRANCIS: It is actually, and what we saw this winter was truly not the polar vortex. The real polar vortex actually refers to the general circulation of air around the poles, so there's a polar vortex in the Arctic and there's another one around the South Pole. What happened this past winter that kind of got misnamed the polar vortex, really was that we had one of these big southward dips in the jetstream in combination with the big northward swing over California and the Eastern Pacific. Because we had this big southward dip in the jet stream, a very wavy pattern, it allowed the Arctic air to plunge southward over much of the eastern half of the country. And because the waves were so big in the jet stream that made that pattern very persistent so it hung around for a long time.

As sea-ice melts, polar bears lose some of their habitat. (Photo: Scheherazade Al Arab; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

Yeah it was called the polar vortex and it kind of caught on because vortexes sound dangerous, and sounds like you're going to get sucked down a hole or something like that. Ultimately, even though it wasn't really named properly I think it actually did a lot of good because it got the public interested. It got them listening, and we were able to - what I like to call slide a little spinach into the cheeseburger - where you kind of sneak in a little science while they're talking about all this nasty extreme weather that's going on. So we were able to educate the public a little bit about the jetstream, about what the polar vortex really is and why we think these kinds of patterns should be happening more often in the future as it's related to general global warming - which you know kind of seems like an oxymoron to have global warming lead to these very cold patterns, but this is something that we are able to talk about.

CURWOOD: So in your view, Professor Francis, which came first...the Arctic melting causing the atmospheric shifts or the atmospheric shifts changing the sea ice?

Jennifer Francis is a Researcher Professor at Rutgers’s Institute of Marine & Coastal Sciences

FRANCIS: Well, I have to say yes. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

FRANCIS: So what we know is happening is that the ice is disappearing. The cause of the ice disappearing is a combination of a shift in the atmospheric pattern back in the late 1980s, so we had this shift in the winds in the Arctic that caused a lot of ice to blow out of the Arctic and into the North Atlantic Ocean. This was a natural shift, we've seen shifts like this before, but it just happened to be an unusually strong one that lasted several years, so we lost a lot of extra ice from the Arctic.

Over the last few decades, however, that ice has been thinning and it's been thinning because of increasing greenhouse gases, so that when it does melt back in the summer as it normally does, a lot more of that sun's energy gets absorbed into the Arctic Ocean, which then contributes to even more melting, so we've gotten into this vicious cycle that means that the more ice we lose the more ice we melt and the warmer it gets in the Arctic, and so we're in the situation now where it really can't recover.

CURWOOD: What does that mean?

FRANCIS: Well it means that we are in for a lot more evidence of climate change. We're already seeing an increase in heat waves. We're seeing an increase in the occurrence of heavy downpours and heavy precipitation events. These are completely expected as a result of the effects of global warming because a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor and more moisture, and so when it does rain, it rains harder. We're seeing an increase in drought in certain areas, so we are changing the climate system in fundamental ways. People just need to start realizing that and realizing that we're not going to turn this thing around unless we can really come to grips with figuring out ways to put less greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Francis is a Research Professor at Rutgers University's Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences. Thanks for explaining things to us today.

FRANCIS: It was my pleasure.

Related links:

- Read the study on how Arctic sea-ice influences Eurasian winter weather

- Jennifer Francis is a Researcher Professor at Rutgers’s Institute of Marine & Coastal Sciences.

- Read and watch videos about Arctic Sea-ice melt on NASA’s website

- Danish artist melts 100 tons of ice as a stark reminder of climate change

[Music: The Whitest Boy Alive “Rollercoaster Ride” from “Rules” (Asound/Bubbles 2009)]

Declining Oil and Divestment

Fossil fuel divestment activists at University of Washington (Photo: Light Brigading; CC 2.0)

CURWOOD: A gallon of gas now goes for less than $3 in some places in the US, and it hasn’t been that cheap since 2010. And oil has dropped to about $80 a barrel and speculators bet it won’t increase much in the next five years. The decline in oil is pushing down profits and stock prices, making it less attractive to investors. Elizabeth Douglass is a reporter for InsideClimate News who covers fossil fuels and the divestment movement. She joins us now on the line from Indianapolis. Welcome to Living on Earth.

DOUGLASS: Thanks very much.

CURWOOD: So, Elizabeth, how do these low crude prices affect the profitability of oil extraction? At what point is it not profitable to extract oil from the ground?

DOUGLASS: It depends on the field. It's quite variable even within a single company and even within the same oilfield. Eagle Ford in Texas for example - one field at break-even point might be $67 and another place it might be $74. All the majors: Exxon, Shell, BP, all of them have been getting a lot of pressure from shareholders about all the money they're spending on particularly very expensive projects like the tar sands and deepwater oil drilling off Brazil, things like that...they cost billions and billions of dollars. And investors would rather have that money returned to them either in dividends or stock buybacks and so they're really forcing the oil companies to scale back on their big production projects.

In some parts of the country, gas prices have fallen well below three dollars a gallon. (Photo: Ricky Romero; Flickr CC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now what's the immediate impact of low oil prices from a climate perspective do you think?

DOUGLASS: That's sort of a double-edged sword because if you have really low oil prices that can stimulate growth in the economy and our economy is still very heavily dependent on oil, so environmentalists, for example, like oil to be very expensive because then consumers drive less, they react to those higher prices. So the concern would be lower prices would be counterproductive on a climate front.

CURWOOD: But?

DOUGLASS: But if you have low oil prices that may bring home the point to oil companies that there are real significant shifts in the world and there's going to be a lot less interest in using it on the long-term, so it could be a shot across the bow for them to recognize that climate change is real and that it’s a real long-term threat to their business.

Divestment activists at Tufts University (Photo: James Ennis; CC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, the fossil fuel divestment movement has recently been urging people to pull their investments from fossil fuel companies. How is that movement reacting now to this dip in oil prices?

DOUGLASS: I think they're reacting cautiously because they know by watching the oil market that things are changing all the time, so they would hate to hang their hat on something that might be fleeting. I think they are laying low on this and letting other people point out, for example, that this is showing us just how volatile these stocks can be, how uncertain it is as a way to undermine the notion that these are no-fail investments and that's really the way they'll probably use this kind of the dip in oil prices. It's not their primary argument. Their primary argument is that climate change is a threat to the world and investing in oil companies is counterproductive.

Expensive fossil fuel extraction projects including Tar Sands mining in Alberta are less profitable with the low price of crude. (Photo: Pembina Institute; CC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So who out there is making the economic argument about the divestment that, well, these stocks aren't quite as guaranteed as they once were in the past?

DOUGLASS: On the economic side there are groups like Ceres and others who are pointing out that if we stick to the climate change projections then we really can't burn even the fossil fuels that are already on the books of these companies. Those companies have a lot of reserves of oil and natural gas and coal and they're all built into the stock price, so their argument is if they cannot burn or sell much of the basis of the assets they have, then their stock prices are considerably overvalued.

CURWOOD: So how is the fossil fuel divestment movement doing around the world? I understand that universities in the UK have gotten involved, pension funds in Scandinavia that sort of thing?

Recently fossil fuel investors have been complaining to oil companies about expensive development projects like the Alberta Tar Sands. (Photo: Light Brigading; CC 2.0)

DOUGLASS: Um hmm. It's a slow process, but it's actually picked up some momentum. I don't think anyone would tell you that it that is affecting Exxon or any of those other companies at this point, but it did elicit a response from Exxon recently when they put a letter on their website, a blog item basically, countering the divestment arguments and we hadn't seen that yet from oil companies to that date, so it means it was at least on the radar screen and that does mean that it's something they're watching.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think fossil fuel companies are scared by the divestment movement?

DOUGLASS: Well I think there's a divergence on that front. If you're a coal company you've got a lot of problems, one of them is divestiture. A lot of universities will find it pretty easy to divest their holdings in coal because their stocks have been crushed. If I'm an oil or gas, natural gas company, I'm not all that concerned just yet. It's not big enough yet.

Elizabeth Douglass is a reporter for InsideClimate News. (Photo: Ann Perry)

CURWOOD: At what point does it become big enough?

DOUGLASS: I think when you start seeing the largest institutions divesting in a quick way and money flowing out of the stocks, they'll have to be reacting to that. They're able to hold on so far by offering dividends and stock buybacks. That's something that every investor loves.

CURWOOD: So at the end of the day, Elizabeth, what you think about the long-term outlook for the oil industry?

DOUGLASS: That's a million dollar question...I think everyone would like to know that! In United States, demand is not really growing very much. In the transportation section we're going to have higher miles per gallon energy-efficient cars. We have a smaller population who is going to be driving, so forth. The future of oil, I think, revolves around what happens in India and China where there's a whole generation that's going to get into cars and start driving. If those cars don't run on fossil fuels, they're in trouble.

CURWOOD: Elizabeth Douglass is a Reporter for InsideClimate News. Thanks for taking time today.

DOUGLASS: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Read Elizabeth Douglass’s article on oil prices and the divestment movement at InsideClimateNews

- Commentary by Exxon Vice President Ken Cohen on the Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement

- More stories from Elizabeth Douglass

[MUSIC: Blind Pilot “Story I heard” from “3 Rounds a Sound” (Expunged 2008)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: an ingredient of Agent Orange wins EPA approval for GMO crops. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Medeski Martin & Wood “Smoke” from “Uninvisible” (Blue Note Records 2002)]

Agent Orange-Related Herbicide Approved for GMO Crops; EPA Sued

Because farmers come in contact with pesticides more than the general population, they’re more at risk of experiencing the negative health effects linked to pesticides. (Photo: The Speaker; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The first records of pesticides date back some 4,500 years, when the Sumerians used sulphur to control insects and mites. Many of today’s synthetic pesticides are derived from chemical weapons developed during the first and second World Wars. And chemical warfare against weeds has become a constantly escalating conflict as unruly weeds rapidly adapt to new products.

On October 15, the EPA approved one of the latest weapons for large-scale production of genetically modified soy and corn - a combination herbicide called Enlist Duo that includes a key component of Agent Orange, the controversial defoliant used in the Vietnam War. So a coalition of farmers and other environmental groups led by the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Center for Food Safety has taken the EPA to court, charging the agency with failing to properly assess the risk of the herbicide to the environment and public health. Bill Freese is the Science Policy Analyst for Center for Food Safety and joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Bill.

FREESE: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So tell us about this new herbicide Enlist Duo. What's it made of and what's special about it?

FREESE: Well, Enlist Duo is a mixture of Roundup and 2,4-D. Now, Roundup is Monsanto's brand name for an herbicide known as glyphosate. And 2,4-D is one of the oldest herbicides, it was a part of Agent Orange that was used in the Vietnam War. Now, Agent Orange was composed of two compounds, 2,4-D and another 2,4,5-T. 2,4,5-T was the more toxic component of Agent Orange, however 2,4-D is also toxic, and what's special about this herbicide mixture is that it is specifically intended for use on corn and soybeans that have been engineered to withstand these herbicides. These are called herbicide-resistant crops and they're by far the major type of genetically engineered crop that are grown in the world today.

CURWOOD: Who makes Enlist Duo?

Dow AgroSciences has developed a variety of corn and soybeans that is resistant to the Enlist Duo herbicide. (Photo: USDA NCRS South Dakota; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

FREESE: Dow Chemical Company manufactures Enlist Duo, and they've also engineered corn and soybeans for resistance to this herbicide mix. What we saw with the first generation herbicide-resistant crops, that is RoundupReady varieties from Monsanto Corporation, is that there were hardly any weeds that were resistant to Roundup or as you say, glyphosate, the chemical name, prior to their introduction in the mid 1990s. And what happened was these crops became quite popular and farmers used glyphosate exclusively and it resulted in what people are calling an epidemic of glyphosate-resistant weeds. And now unfortunately this is serving as the pretext right? These glyphosate-resistant weeds have become the pretext for introduction of these next-generation GM crops such as Dow’s Enlist crops.

CURWOOD: So who's to say that weeds won't develop a resistance to this new herbicide cocktail like they have to just plain glyphosate?

FREESE: Well, I think it's very clear that they will evolve resistance to 2,4-D and you know the weed science community is fairly clear this will happen. And unfortunately, you know, there's kind of an acceptance of this pesticide treadmill that we really need to get away from.

CURWOOD: Bill, what do you see as the health risks associated with 2,4-D?

FREESE: Well, you know it's not just what I see, it's what medical science has been telling us over the past several decades. There are a number of repeated epidemiology studies by very top-flight scientists which show that 2,4-D exposure is linked to higher rates of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. This is an immune system cancer, it kills about 30 percent of those who contract it and it's really bad news. Parkinson's disease is another disease that is been linked to 2,4-D. We also see potential risks for children, infants, from 2,4-D exposure. There have been a number of studies which looked at that, and that's a very important aspect of the situation, is that children are known to be much more sensitive to adverse effects of pesticides than adults because their systems are developing. And EPA is supposed to account for this greater sensitivity in its risk assessments, but unfortunately it failed to do so with this Enlist Duo assessment.

CURWOOD: Now, the EPA did test 2,4-D on rats. They set limits on when farmers can apply this new herbicide in order to make sure that in EPA’s view it would be safe, but you say their tests and their restrictions aren't realistic. How so?

Monarch Butterfly larva eating milkweed, which is particularly sensitive to glyphosate. (Photo: Doug Bowman; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

FREESE: You know, the way I like to think of it is that EPA regulation is based on virtual reality. As you say, they rely almost completely on tests done on rats that are conducted normally by the registrant, in this case, Dow, and they ignore more relevant medical science that actually looks at impacts in the real world.

CURWOOD: We know that glyphosates are particularly tough on milkweed, which is vital for the survival of Monarch butterflies, it's where they breed. But what are the risks to pollinators in general associated with this herbicide 2,4-D?

FREESE: Well you know, 2,4-D effectively kills flowering plants, and they're the base of the ecosystem. They provide habitat and food to animals including pollinators. Think of flowering plants...they supply nectar, and if they're killed off than that impinges on the populations of these crucial pollinators, bees as well as Monarch butterflies and other insects. And it's particularly problematic in farm country if you think of a state like Iowa, most of the land is taken up with corn and soybean fields, so to the extent that you still have biodiversity in the Midwest it's often very close to corn and soybean fields, and studies show that we're going to have reduced populations of these nectaring plants.

CURWOOD: One of the things that you say in your complaint is that the EPA didn't get right their assumption that an herbicide sprayed on a field would stay in that field. Why is that not a reasonable assumption to make?

FREESE: Well, if EPA had really looked at experience with 2,4-D they would have seen that it's the number one culprit in drift-related crop damage. OK, so this is a very drift-prone herbicide. We know this; there's concrete experience. What EPA does is rely completely on complicated models of pesticide drift that frankly were developed by the pesticide industry and which assume perfect compliance with all sorts of unrealistic conditions. I should say that we tried our best to work through the administrative process. For two years we filed detailed scientific comments on these agencies assessment documents and it just...EPA hasn't listened to us, so that's that's why we've been forced to resort to a lawsuit here.

Bill Freese is a science policy analyst with the Center for Food Safety. (Photo: Courtesy of the Center for Food Safety)

CURWOOD: And you're not the only ones unhappy with how EPA has handled Enlist Duo's approval. Other organizations have filed another lawsuit against the agency. Reuters reported that EPA has been flooded with calls some from doctors, scientists urging it not to approve this herbicide. Why such an outcry over this one particular product?

FREESE: Well, I think there's several reasons. First of all, we're talking about an herbicide that is already fairly widely used that will experience a three to sevenfold increase in use. This is a projection by Dow that's been seconded by the USDA and basically all of the big biotechnology companies have developed similar crops that are resistant to other herbicides—in many cases, two and three herbicides each. So when you look at this in totality it presages a tremendous increase in overall herbicide use dependence and we're trying to steer agriculture onto a more sustainable path where weed control is accomplished with far fewer herbicides.

CURWOOD: Bill Freese is the Science Policy Analyst for the Center for Food Safety. Bill, thanks for much for taking the time with us today.

FREESE: I was happy to be here. Thanks.

CURWOOD: We contacted the EPA and Dow Chemical for comment. The EPA emailed, "We will review the suit and respond appropriately." Dow officials responded that they “support EPA’s registration decision and are confident that EPA will prevail in all of the related litigation.”

FULL STATEMENT FROM DOW AGROSCIENCES:

“Dow AgroSciences is confident that EPA thoroughly reviewed this long-awaited new agricultural technology before registering Enlist DuoTM herbicide for use by American farmers. We support EPA’s registration decision and are confident that EPA will prevail in all of the related litigation.”

Related links:

- The Center for Food Safety’s petition to the 9th circuit court of appeals

- EPA fact sheet on Enlist Duo registration

- Dow AgroSciences press release describing the EPA’s approval of Enlist Duo.

- CFS coalition partner Environmental Working Group’s comments on the EPA’s approval of Enlist Duo

- The Center for Food Safety

Fascinating & Toxic - Traditional Moroccan Tanneries

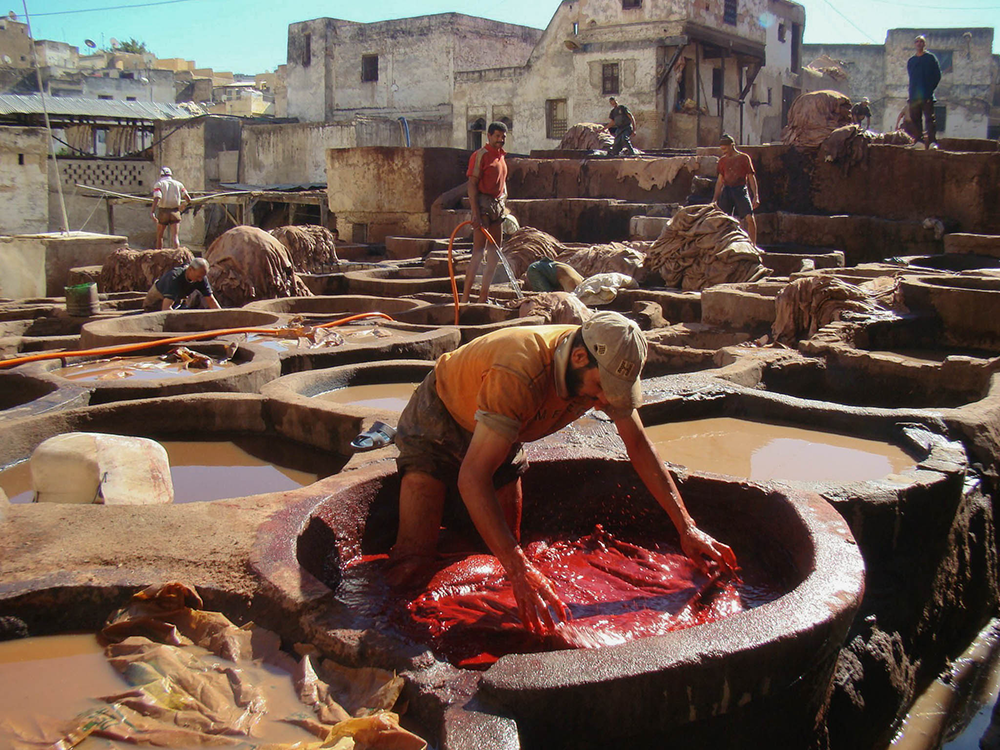

Exposure to toxic chemicals is nothing new when it comes to being a tannery leather worker. It is a job that is highly labor intensive and only pays between $2-5 USD a day based on skill level and production output. This is Chouara Tannery, a traditional tannery located inside the medina of Fez, Morocco. (Photo: Julian Harris)

CURWOOD: Off on vacation now to Morocco. A million people visit this North African kingdom every year, making tourism its second biggest industry after phosphate mining. Visitors flock to the one-time capital, Fez, and wander in the old medina, a walled city-within-a-city where artisans in small shops work and offer their clothing, jewelry and brightly colored leather goods for sale. The tanneries, in operation in Fez since the 14th century, are the biggest draw. But though leather-working is picturesque, there’s a darker side. Reporter Amulya Shankar has our story from the traditional Chouara Tannery.

[TOURISTS CHATTING]

SHANKAR: The stench is overpowering. I’m part of a tour group that has climbed steep steps to the rooftop of the Chouara Tannery shop. Right away, we are greeted with the smell of wet animal skins from the dye vats several stories below. As we peer down, we see hundreds of vats that cover an area the size of a football field. Men stand thigh-deep in murky water, sloshing hides back and forth to soften and color the skins. A sprig of mint we’ve been given is supposed to combat the stink. Sniffing the mint helps, but not much.

REHACK: It’s like visually exactly what you think Fez is going to be, so you can definitely feel like it’s there for you, for the tourist.

SHANKAR: That's Hannah Rehack, an American student studying in Morocco and touring Fez. She’s right. These men stand in cold, chemical-laden water, handling animal skins, all day, every day of their lives, to entertain the tourists who will buy the goods they help produce.

The amount of waste generated by tanneries is staggering. Chemicals, bacteria, and animal by-products are regularly dumped into the Sabou and Fez Rivers. (Photo: Julian Harris)

[SHARPENING KNIVES]

SHANKAR: Two hundred men work at the Chouara tannery in the ancient city of Fez. Some of them scrape the hair from the skins using razor-sharp knives. Once the scrapers are finished, the skins are dumped into the vats where others take over the softening, dying process. The work never stops, the noise never ceases, and the air is filled with the pungent smell of wet animal hides.

[WATER SPLASHING]

SHANKAR: But it’s the water that’s the main problem. Chromium has been a major ingredient in the tanning process since the 1800s. Its unique properties produce versatile leather that can be used for making saddles, sturdy shoes and suede jackets. Chrome-tanned leather handles high temperatures, absorbs less water, and dyes more easily. But chrome is also a known carcinogen, and the water in the vats is loaded with the chemical. Not a good thing for the men who spend their days up to their thighs in it.

SHANKAR: Abdul Kadhr, who is 32, has been working at the tannery for 16 years.

KADHR: [SPEAKING IN ARABIC]

SHANKAR: Kadhr claims he has had no health effects from his work in the tannery. Perhaps he’s been lucky. According to the World Health Organization, those who work in close contact with chromium can suffer from immune system and respiratory problems.

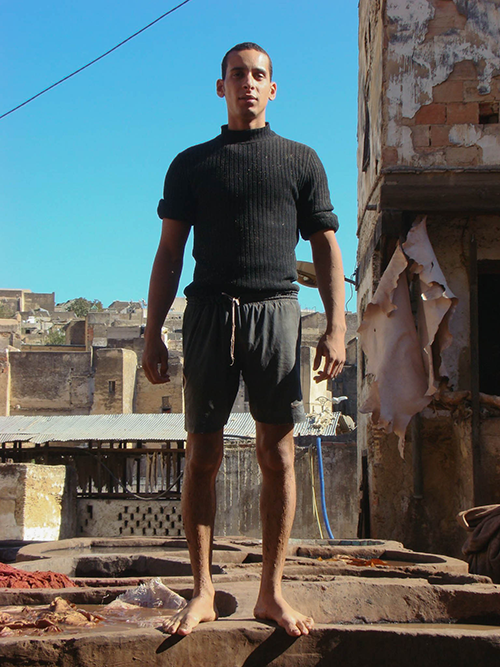

Tanner Abudul Kadhr said, “I am married and I have kids and I work for myself and my family and thanks to Allah I make enough for myself and my family…This job is good for the health…only natural dyes are used, it is not toxic…people work until they are 80 sometimes and are in good health.” However, there are studies that dispute this and actually state that this job is linked to immune and respiratory illnesses. (Photo: Julian Harris)

SHANKAR: And there are heath concerns beyond the risks for tannery workers. About every 25 days, the dyes lose their potency and need to be refreshed. So chemical-laden water from hundreds of vats is dumped into the Fez River every month.

Ismail Aloui is with the Agency for the Development and Rehabilitation of Fez. He says chromium contaminates the city's food supply and sickens people.

ALOUI: They suffer directly. It’s a health problem, daily problem.

SHANKAR: An official at the water department in Fez, Mohammed Meziani, admits that chromium and other chemicals are fouling the water but he argues that the city’s drinking water is unaffected.

MEZIANI: We know the chromium is toxic. But it’s downstream. The water we drink is from upstream.

SHANKAR: Steven Lange is a U.S. expert on tanning. He directs the Leather Research Laboratory at the University of Cincinnati. He says 80 to 90 percent of tanneries worldwide still use chrome, but modern tanneries have high safety standards. Lange says the difference lies in the controls.

Tanner and salesman Abdul El-Machour stated, “I was born like 70 or 80 meters from the tannery and I started to come to the tannery when I was like four or five years old, not for work, but for playing…When I was 8 years old, I do very bad accident…I fell from tannery terrace into the vats.” (Photo: Julian Harris)

LANGE: We do want to make sure that our industry doesn’t have a negative impact on the environment. In the US, we have the strict laws, and all the tanneries here, they have their processes controlled. Modern tanneries now will have water collection systems to minimize water usage and to reclaim the water and reuse the water. They will have a process in place to capture any leftover chrome from the wash processes, to recycle it and use it again.

SHANKAR: Tanneries in developing countries have a long way to go to meet health and environmental safety standards that are the norm in the developed world. But even in Morocco there are new tanneries, not far from the old ones, that provide safer alternatives.

[MACHINERY IN THE TANNERY]

SHANKAR: 55 modern tanneries outside the old city of Fez use high tech filtering systems to produce less pollution, and they are much safer for the environment. Mohammed Behara owns the modern Saiss Tannery in an industrial complex on the outskirts of Fez.

BEHARA: [SPEAKING IN ARABIC]

Three traditional tanneries in the medina of Fez (including Chouara) practice traditional methods of washing, smoothing and coloring animal skins to produce soft leather goods. (Photo: Julian Harris)

SHANKAR: Behara acknowledges that new facilities like his don't project the air of romance that the historic operations offer. His tannery does not have a shop, and they don’t attract visitors. The business model is different. The leather tanned here is shipped to artisans in cities all across Morocco. While the old tanneries are about producing leather goods for tourism, the modern tanneries focus on the tanning process.

And today that process includes an awareness of environmental issues. For instance, they cluster the tanneries close together so all the water can be collected and treated centrally. Steven Lange says it’s a smart strategy that can save more than just money.

LANGE: The whole idea is to, not just to reduce the chrome effluent, but effluent overall and reduce the water usage. Water’s becoming a very expensive commodity, and we know there’s a limited supply, and you want to preserve that as much as possible.

SHANKAR: Back at the Chouara Tannery, our tour group heads to the terrace shop, one of many that stop here to see the results of the labors going on below. Bags, slippers, and jackets of every color burst from the shelves as shopkeeper Abdul El-Machour shows off his wares to dozens of eager visitors. It’s no surprise that a single shop can make $1,200 to $1,800 a day during the summer.

American student Franny Krieger says she loved the aesthetic of the leather despite the pushy sales pitches.

KRIEGER: It’s beautiful … it’s a buyer’s paradise in there, and they really do try to get you to get you to buy something.

Abudulhay Sadaq, 23, was an apprentice tanner since he was 13 years old. “When I was very small, like 4 years old, I loved my father’s job…and everyday I would go from the school to the tannery…I hope they will bring me back to the school to get a good mind, but I am a little too old to study now,” he said. (Photo: Julian Harris)

SHANKAR: Shopkeeper El-Machour says that the old tanneries are a vital part of Morocco’s tourism industry.

EL-MACHOUR: Now Morocco is like a famous country in the world… it’s important for the economy of medina and it’s important for the tourism also. I think the tannery stays forever.

[KNIVES SHARPENING, WATER SPLASHING, WORKERS TALKING]

SHANKAR: Eventually polluted water and contaminated land, not to mention workers’ health, will have to be addressed. And Steven Lange argues new, creative approaches could be used to preserve some of the magic that tourists are looking for. Maybe the old tanneries could be re-plumbed so that the effluent could be carried away safely without compromising the historical aesthetic.

LANGE: Could it be they could do something like what Disney does, you know, have it look like it’s old, but actually using modern technology in the background?

SHANKAR: Whether tourists – and the traditional tanneries – would accept this Disneyfication is another matter. For now, watching leather being made in the traditional way, taking home the beautiful products, and even enduring the smells of the tanning process is what visitors have come to expect. But for the citizens of Fez and their environmental advocates, change has to come. Their health, and the health of their land and water depend on it.

For Living on Earth, I’m Amulya Shankar in the old medina of Fez, Morocco.

CURWOOD: Thanks for that story to Round Earth Media, SIT Study Abroad, and reporter Oumayma Sbila. There are photographs and more at our website, where you can hear our program anytime, or download the audio. The address is LOE.org. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- WHO reports on Chromium's negative health effects

- WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality, concerning chromium

- The Agency for the Development and Rehabilitation of the city of Fez (ADER-Fès)

- The Choura Tannery’s Trip Advisor page

- Steven Lange is director of the Leather Research Laboratory

- Round Earth Media helped produce this story.

[Music: Dahmane El Harrachi “Ya Rayah” from Sahara Lounge (Putumayo 2000)]

CURWOOD: And we’d like to hear from you. You can post your thoughts or reach us at comments@LOE.org. Once again, comments@LOE.org. Our postal address is PO Box 990007, Boston, Massachusetts, 02199. And you can always call our listener line, at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-9988.

Coming up...how the fall of a repressive Balkan regime was bad news for migrating birds. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: John Coltrane “Syeeda’s Song Flute” from “Giant Steps” (Atlantic 1959)]

Lead-Free Ammunition Saves Waterfowl

Foraging geese (Photo: © Putneypics)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

[MUX - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: Across the globe as the seasons change the vast flyways are thronged with migrating birds. And as Mary McCann explains in this BirdNote®, one fall ritual in US marshes and other wetlands is now in the main, less toxic, though not necessarily less deadly.

BirdNote®

Waterfowl and Lead

Male Mallard lands in a field. (Photo: © Joby Joseph)

[Calls of Canada Geese, Trumpeter Swans, Mallards]

MCCANN: Every autumn, millions of ducks, geese, and swans return south from remote northern breeding grounds to winter in temperate North America.

[Calls of Canada Geese, Trumpeter Swans, Mallards]

MCCANN: And every autumn, the long-standing tradition of waterfowl hunting is reenacted.

[Individual Mallard]

Trumpeter Swan (Photo: © Mark Witten)

But one important feature of that hunting tradition has changed. Beginning in 1991, waterfowl hunters were required to switch from lead shotgun pellets to pellets made of non-toxic metals.

In the past, foraging ducks, geese, and swans often ingested lead shot that had fallen to the ground. Waterfowl must swallow hard particles so their gizzards can grind up hard foods, like grains. Unfortunately, they can’t tell a lead pellet from a small pebble.

[Male Mallards]

Even two pellets of lead in a duck’s digestive system can cause a slow death from the effects of lead poisoning. Many birds were affected. The switch to non-toxic shot has made a positive difference for waterfowl.

Adult and immature Trumpeter Swan forage in a field. (Photo: © Jerry McFarland)

[Male Mallards]

But lead shot is still widely used for the hunting of gamebirds like pheasants, which often share areas used by waterfowl.

South Dakota now requires non-toxic pellets for all small game-hunting and even target-shooting. And hunters elsewhere who are concerned about conservation, have made the switch to protect the future of the birds, the habitat, and the tradition they value.

[Calls of Canada Geese and Trumpeter Swans]

I’m Mary McCann.

Canada Goose family (Photo: © Ken Slade)

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird audio provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Canada Goose calls recorded by W.W.H. Gunn. Trumpeter Swan calls recorded by J.M Hawthorne. Mallard calls recorded by A.A. Allen.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2014 Tune In to Nature.org October 2014 Narrator: Mary McCann

http://www.abcbirds.org/abcprograms/policy/toxins/lead-fact-sheet.html

CURWOOD: You’ll find photographs of ducks and geese and swans at our website, LOE.org.

Related link:

More about waterfowl and Lead on BirdNote’s website

Albanian Migratory Bird Poaching

Ferruginous ducks. Historical records suggest there may once have been millions of these ducks in Albania. The last breeding pair was seen in the country in 2003. (Photo: © Martin Schneider-Jacoby/EuroNatur)

CURWOOD: And now to a darker story of bird hunting. Millions of birds migrating between Africa and Europe are being illegally shot, many of them in the salt marshes of Albania along the Adriatic Sea. Phil McKenna is a freelance environmental journalist. He investigated this illegal slaughter, and wrote about it in Yale University’s online publication E360. Phil McKenna came into our studio to talk about Albania's killing fields.

MCKENNA: Albania’s often referred to as the wild wild east of Europe and in many ways it really is. So when I went there it was astonishing to see. You don't see birds in the sky. In parts of Albania you don't even see trees on the ground. It's just really the natural resources there have just been under assault for decades now.

CURWOOD: So, let's do a little geography lesson here. Albania is on what flyway for birds?

MCKENNA: Something called the Adriatic flyway. Albania and the Balkans are really a funnel between Europe. So you have birds coming from north, central, eastern Europe all funneling down all through the Balkans along the coast of Albania along the Adriatic Sea before they cross the Mediterranean and then crossing the Sahara down to the Sahel region of Africa where they will spend the winter.

Highly restricted during Communist times, guns are now commonplace in Buna Delta, Albania and, though increasingly rare, some hunters still travel by donkey cart. (Photo: © Martin Schneider-Jacoby/EuroNatur)

CURWOOD: What kind of birds are being hunted along this flyway?

MCKENNA: Anything that flies. So really, yeah, waterbirds, ducks, geese, shorebirds. We saw a Marsh Harrier when I was there - one of first birds we saw - and the biologist I was with pointed it out and then quickly said, "It won't last a week in this marsh." It's amazing when you go there. The habitat is excellent yet empty. Right now what happens is that a lot of birds know that if they go in there they're going to be shot and they'll stay out at sea. They need to come in, they need to eat, but they know that the risk is too great. And was happened most recently is Albanian hunters will now get in their speedboats and they will race to them in the open ocean and start shooting there.

CURWOOD: Shooting birds from moving speedboats?

MCKENNA: Yeah, which is completely illegal and completely foreign to think of as bird hunting here. One of my sources said, you know, "This isn't bird hunting, this is massacre."

CURWOOD: Most people, when they think about poachers, they're thinking about big game hunters in Africa looking for rhino horns or ivory. Who are the Albanian poachers?

Ducks and other water birds are a common sight in the markets of Shkodra, Albania. (Photo: © Darko Savelijic)

MCKENNA: It all started during the communist era in Albania. You had these millions of birds migrating through each spring and fall and they were completely off-limits, even the marshes oftentimes were off limits to the Albanians. Albania was one of the most repressive countries in the world during the communist era, and the leaders of the country were all into bird hunting and would go into these reserves set aside just for them. They were the only ones who are allowed to hunt. When all of this came crashing down in 1991, all of the Albanians wanted to do what their leaders had been able to do, use kind of this forbidden fruit. So guns started flowing into the country - everybody got one - and they all started going into the marshes and wetlands trying to shoot birds.

CURWOOD: Now, elsewhere in the Adriatic, I'm thinking of other countries, Italy, etc., there are pretty tight restrictions on shooting birds I gather?

"No Hunting" signs are routinely ignored in the protected wetlands of northern Albania's Buna River Delta. (Photo: Phil McKenna)

MCKENNA: There are, getting more so each year, and there's also this great tradition especially in Italy of birds and cuisine, eating birds, songbirds, you name it. So what happens now is a lot of Italian hunters who want these birds, want to shoot these birds, will come on these hunting vacation packages to Albania where they will come and have unlimited hunting for three or four days, taking back hundreds and hundreds of birds.

CURWOOD: Wait, you're telling me that this is a tourist phenomenon?

MCKENNA: About one in five hunters in Albania is thought to be an Italian, or at least that was the case until earlier this year when Albania announced a two-year ban on all hunting nationwide. We know that this ban isn't entirely effective, but the thought is that it's at least putting a significant dent in the number of foreign tourists coming into the country.

Poachers throughout the region use bird decoys and play tape-recorded bird calls to attract birds. Other tactics employed by illegal hunters in Albania include hunting inside national parks and other protected areas, hunting at night when birds flock together, using nets and glue sticks to catch song birds, and chasing ducks and other water birds in speedboats at sea. (Photo: © Martin Schneider-Jacoby/EuroNatur)

CURWOOD: So, what did people do with these birds once they kill them?

MCKENNA: I think a lot of it's just for the sport of shooting. Some may not even be eaten. There's also a very thriving market for cuisine. I went to very high-end restaurant in Tirana, the capital of Albania, very close to the US embassy, where they were selling mallards, they were selling something, blackbird, Woodcock for $18, $20 a pop.

CURWOOD: That's not cheap.

MCKENNA: That's not cheap.

CURWOOD: So what has been the impact of hunting on all the bird populations there?

Shotgun shells are often a more common sight than birds in Albania's coastal wetlands (lagoon near Vlora Albania) (Photo: Phil McKenna)

MCKENNA: Well, we know in a greater flyway called the Mediterranean Black Sea flyway, one third of all birds going through the region are in decline. We also know that a couple of species, the Slender-billed Curlew, which is this very graceful wading bird, is likely extinct. One of the last ones was seen just across the border of Albania and Montenegro in 2006. Another bird, the Ferruginous Duck, this very pretty reddish sort of chestnut brown duck, once likely numbered in the millions passing through Albania, now is entirely extinct within Albania.

CURWOOD: You say the Albanian government has put out a hunting moratorium in place. How effective has that been so far?

Peter Sackl of Universal Museum in Joanneum, Austria stands in a limestone bunker. Hunting hides such as these are commonly found within officially protected areas along Albania's coast. (Photo: Phil McKenna)

MCKENNA: From all accounts that I hear it hasn't been effective at all. There's this large conference, the Second Adriatic Flyway Conference, and during the conference a number of the attendees, they went out to one of the nearest national parks, and while they were there in the middle of the day, not the best time for hunting, but yet they still heard gunshots.

CURWOOD: How about when you visited? What did you hear or see?

MCKENNA: I heard the same. I saw, like I said, very few birds. In the beginning of my trip in northern Albania; towards the end I went down to southern Albania with Taulant Bino, he's the former environment Deputy Minister of Environment in Albania and the country's leading ornithologist. He took me to some spots that were still quite well protected, but yet even there we were hearing gunshots throughout and shotgun shells were littering the ground. And at one point it was like paving stones, these multicolored shotgun shells all over.

Phil McKenna (Photo: PhilMcKenna.com)

CURWOOD: Now, what about the conservation groups, the nongovernmental organizations. What are they doing there?

MCKENNA: A lot of this is led by EuroNatur, which is a German conservation group. They are very concerned because they rightfully view these, not just as Albanian birds but as Europe's birds, and they're being killed in Albania. They want to go to Albania and protect them.

CURWOOD: Now in your piece you mentioned that Albania is a candidate for admission into the EU, the European Union. How does all this slaughter of birds affect that issue?

MCKENNA: Right. Officials I spoke to at the European Commission were very concerned about this issue. They attended the recent Adriatic Flyway Conference and told me, quite frankly, if Albania doesn't clean up its act this could be a stumbling block entry into the EU.

CURWOOD: So, Phil, how do you think this is going play out in years ahead?

MCKENNA: My hope is that we're really at a key point now with the European Commission looking very closely at what's happening in Albania. My hope is that they will find a way to kind of force upon Albania or maybe help them to better protect birds. On paper, Albania has great protection for… for birds and other wildlife. It's really when you get down to what's happening on the ground that things need to change. And part of that is Albania is still a very poor country. They don't have enough fuel to put in their trucks, for the rangers to go to patrol the parks. There may be a solution, where the European Commission, the European Union finds a way to fund Albanian rangers to go out and do their jobs.

CURWOOD: Phil McKenna is a Freelance Environmental Journalist. Thanks for taking the time with us today, Phil.

MCKENNA: Steve, thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Read Phil McKenna’s “Albania’s Coastal Wetlands: Killing Field for Migrating Birds” in Yale’s e360

- Euronatur’s website

[MUSIC: BALKAN MUSIC]

Beyond the Headlines

Phragmites is a resilient, invasive reed that emits an acid from its roots, which helps it to crowd out native plants in swamplands. (Photo: John Lillis; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time now to check in with Peter Dykstra and find out what’s happening in the world beyond the headlines. Peter publishes Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org, and he’s on the line now from Conyers, Georgia. So Peter, what’s up today?

DYKSTRA: Well hi, Steve, you know I grew up in northern New Jersey, right on the edge of Hackensack Meadowlands, one of the biggest salt marshes on the east coast and historically one of the worst urban dumping grounds in America. It was a really good place for me to learn about environmental impact.

CURWOOD: So let’s see, the Jersey Meadowlands is home to a football stadium, lots of trash and toxic waste, and the late union boss Jimmy Hoffa, right?

DYKSTRA: Well yeah, we still need to slap an “allegedly” on the Jimmy Hoffa thing, since he’s never been found. But the toxic waste and trash, definitely, and despite all our abuse, the Meadowlands are coming back a little. Today, one of the biggest threats to coastal wetlands, like the Meadowlands, and freshwater swamps are invasive species like phragmites, a reed that crowds out native vegetation and is now found in every US state. It runs deep roots, emits an acid that helps crowd out native swamp plants, and despite efforts to burn it, and poison it, and plow it under with bulldozers, it’s still thriving, but a new effort may hold some promise.

CURWOOD: So let me guess, they’re being done in by the same guys who allegedly got Jimmy Hoffa?

DYKSTRA: No, the hero of this story is the goat. A story this week reports that experiments led by Duke University show promise – one of them in a Maryland wetland, the other experiment at Fresh Kills, the immense former landfill on Staten Island. Goats think phragmites are delicious. It’s not a perfect solution, and in the experiment they still used herbicides to help keep the unwanted reeds from returning, but the lowly, low-tech goat may help get the job done.

CURWOOD: And I understand they even eat poison ivy as well.

DYKSTRA: They do indeed! Ready for another wetlands story?

CURWOOD: Sure, ya got one?

Nansha Wetlands Park, China (Photo: Kathy & Sam; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: When we hear about China’s breakneck economic expansion, we often hear about CO2 emissions, or choking smog, or disastrous water pollution, or vanishing water supplies, or a dam project displacing millions of people, or vanishing wildlife, or contaminated food, or..

CURWOOD: OK, Peter, we get it. China’s got a lot of environmental baggage. I take it you’ve got more?

DYKSTRA: I believe I do. With so much of its population and urban growth and industrial activity along the coastline, it’s reported that China may have lost as much as 50 percent of its coastal wetlands to erosion, development, and reclamation projects to convert wetlands to farms, living space, or industrial facilities. One researcher said those losses could translate to both ecological disaster and real financial harm – billions of dollars in losses to fisheries and flood control, to say nothing of the harm to migrating birds and a lot more.

CURWOOD: And like so many topics, there’s no such thing as a free lunch, except maybe for those goats you mentioned. So hey, take us back for our weekly trip into the environmental time machine. What have you dredged up for us this week?

DYKSTRA: OK, this was big in my childhood, and big for a lot of American kids, but it was an absolute phenomenon in Japan. 60 years ago this week, “Godzilla” premiered in Japanese movie houses.

[GODZILLA ROAR]

Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster movie poster. (Photo: Tom Simpson; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And a movie genre was launched, all with environmental undertones.

DYKSTRA: Right, it was all about radiation, and specifically Godzilla was upset by US nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific. Remember this was 1954, only nine years after the end of World War II and Hiroshima and Nagasaki and atomic bombs were understandably a big deal in Japanese culture.

CURWOOD: But if Godzilla was mad at US nuclear tests, shouldn’t he try to destroy San Francisco or LA not Tokyo?

DYKSTRA: Spot on, Steve, I never figured that one out, either. But two things: first, there’s perpetual controversy on the Internet over whether Godzilla was actually a “he”. And secondly, he – or she – later became a hero instead of a villain. Notably in a 1971 movie when Hedorah, a hideous, smoke-belching blob of a monster tried to pollute Tokyo to death, and some young hippie environmentalists summoned Godzilla to literally clean up the town. Yes, Godzilla versus the Smog Monster was an environmental classic. And Steve?

CURWOOD: You think they should send Godzilla to China now?

DYKSTRA: Er, no, but could you please do me a favor and give all the people who think I’m making this up the web link?

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Peter Dykstra is the publisher of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks so much, Peter, for taking the time today.

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve. Thank you and we’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And you can get a link to all the things we’ve been talking about – including Godzilla – at LOE.org.

Related links:

- Duke’s press release: Goats are better than chemicals for curbing an invasive marsh grass.

- Read the Duke study about goats and phragmites control

- Sixty years ago this week, “Godzilla” premiered in Japanese movie houses.

- China’s coastal development is wiping out fish and birds

- Godzilla versus the Smog Monster – The 1971 film’s imdb page.

[MUSIC: Prince “Darling Nikki” from “Purple Rain” (1984 Warner Bros.)]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, pollution detectives are finger-printing dirty water.

JACKSON: We use the isotopic signatures and the ratios of different elements to distinguish between conventional wastewater from oil and gas wells, and the newer hydraulically fractured wells.

CURWOOD: How forensic chemistry is helping solve fracking water mysteries, that's next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Oneohtrix Point Never “Remember” from “Replica” (Mexican Summer/Software Recording 2011)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis are all part of our team. Our show was engineered by James Curwood with help from Karlyn Daigle. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth