December 27, 2013

Air Date: December 27, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Power of Stories

View the page for this story

Living on Earth’s winter holiday tradition featuring legends and seasonal stories continues. Storyteller Lee Ellen Marvin joins Steve Curwood to share stories about children and wolves, as well as some tips on becoming a good storyteller. (09:30)

.jpg)

Native American Tales

View the page for this story

Wampanoag storyteller Medicine Story spins a tale about the shortest days of the year, and how the Wampanoag people persuaded Grandfather Sun to return. And Cherokee storyteller Gayle Ross shares seasonal tales of the importance of the warmth and the promise of spring handed down in her family. (18:50)

Stories of the Night Sky and an English Wassail

View the page for this story

Writer, storyteller, and musician Joseph Bruchac offers Iroquois myths, first about the twinkling stars of the Pleiades in the winter sky and then about why life on earth continues though the long, dark nights of mid-winter. Then storyteller Diane Edgecomb shares an English tale in which barnyard animals get the last word. She closes with a Cherokee myth about the trees that stay green all winter long, the evergreens. ()

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Lee Ellen Marvin, Medicine Story, Gayle Ross, Joe Bruchac, Diana Edgecombe

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. To celebrate the season, we bring you stories this week – stories that help explain these long dark nights of mid-winter ---

MEDICINE STORY: @ :59 the days just kept getting shorter and shorter and shorter. And eventually they were so short that well, people would be jumping up as soon as they saw the sun come into the village. ///and run out, and the sun would already be going down and that was the end of their day. :16

What the Wampanoag did to persuade Grandfather Sun to return -- And we share a Native American tradition that might benefit us all –

BRUCHAC: @ 6:27 And what they would say when they greeted each other this time, what they would say was, "An halom mawi, casia palwea walang." Which means, "Forgive me for any wrong I may have done you in the past year." :13

We hope you’ll forgive us any wrong – and stay with us now for those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

The Power of Stories

A grey wolf stalks (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. Here in New England, we’re deep in the deepest midwinter.For many of us this is a time for reflection, introspection and gatherings with friends and family.It’s a time to look back on the year, and the years and refresh our shared memories and traditions. A tradition we’ve had for many years here at Living on Earth is to feature stories and legends in our midwinter program, and not our usual mix of environmental news, views and reviews. This year we’re looking back into our archives, to find some of our favorite stories and storytellers – and we found Lee Ellen Marvin.

She teaches at Ithaca College, where she’s a strong advocate of the value of the arts to our mental and physical health; and of the power of stories to illuminate the deeper realities of our existence. She had some advice for us on how to become a good story-teller yourself, to amuse and maybe enlighten your own friends and family. And Lee Ellen Marvin chose to entertain us with stories of children and wolves – not the cautionary tale of Red Riding Hood and her grandmother – but other wolf stories both familiar and unknown; both true, and legendary.

CURWOOD: The stories we've heard so far reflect the deep history of traditional cultures. But most stories begin with personal experience and wend their way into legend. In a moment we'll hear a modern story from Lee Ellen Marvin, a teacher and a graduate student of folklore at the University of Pennsylvania. Lee Ellen's tale is one of human experience, about a child's encounter with a wolf. She joins us from member station WHYY in Philadelphia. (:28) (@ 49:23) Lee Ellen, I've noticed many cultures have stories about special relationships between children and wolves.

MARVIN: Yes, there are several. One of the most famous is the Roman legend of the creation of the city of Rome by Romulus and Remus, noble children who had been tossed into a river by their evil uncle. And they were rescued by a female wolf who suckled them. Also a bird came and put food in their mouth. Then later they were found by a shepherd and taken in, and they went on to become the famous founders of the city of Rome. There's also the legend of wolf girl, from the ranching days of Texas, about the 1850s. A rancher had gone off to get help while his wife was in labor and she died, giving birth to a girl. And when people came back to the ranch, they discovered that the girl was missing. Years later, they saw a wild girl running with a pack of wolves, and so they had to assume that this was that little child who had been lost to her parents. (131 - 50:30)

CURWOOD: I'm wondering if you could tell us a bit about the story we'll hear today.

MARVIN: This story is a true story about a woman's experience when she was a little girl in the woods of Pennsylvania in 1923. Her name was Tessie Lutz.

CURWOOD: All right. Now let's hear that true story from 70 years ago. Tessie and the Wolf.

MARVIN: It goes like this. In 1923, when Tessie Lutz was just 7 years old, she went out with her father to chop wood. The Pennsylvania forest was covered with snow, and her father's ax sung a steady rhythm: a-cha, cha, cha. Which lulled Tessie. She sat on the wagon bench and played with her doll and thought about Christmas just a few days away.

Then the chopping stopped, and the woods were eerily quiet. Tessie looked up to see her father resting his ax and looking across the clearing. He was watching a beautiful dog, an unusual dog taller and broader in the shoulders.

"What's that beautiful dog, Daddy?"

"Well that's a wolf, honey. They've been gone for almost 50 years, but there it stands."

Tessie's father quietly reached under the bench of the wagon and he pulled out a rifle. As he took aim, Tessie went over and tugged on his jacket. "Daddy -- why are you going to shoot the beautiful dog?"

"It's not a dog, honey. It's a wolf."

Grey wolf in winter (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

"But it isn't hurting us."

The father looked at Tessie, and then at the wolf, and finally at his gun. "Well, I guess you're right. Nothing's been harmed."

He went to put the gun back in the wagon, and finally the wolf took fright, after watching them boldly for quite a while, and he scampered off into the bushes, quickly lost on the darkness of the forest. Then soon it was Christmas Eve. Relatives came pouring into the house, all hustle and bustle, but Tessie was impatient to open her presents. To make the time go faster, she slipped outside to play.

The forest was gloomy in the very last of the evening light. Big clouds hung overhead, and the wind blew hard. But she went into the woods to find her favorite little clearing. And when she got there, the storm let loose. The snow and the wind stole away the twilight. Tessie turned for home but it was dark as night. The wind stung her eyes. And as she struggled against the storm, she couldn't find her way back. Nothing looked familiar. She screamed for her parents, but the wind tossed her words back into her mouth. And she was lost. (4:20)

Finally she fell in a worn-out heap under a pine tree. She was too cold to move, and too tired to care. But something warm and soft and rather heavy fell against her. Tessie opened her eyes long enough to see that beautiful dog, the one her father called wolf, curling around her like a living blanket. Tessie stopped shivering. She wasn't afraid any more, not with the company of the wolf to keep her through the night. Still tired, she snuggled down into its gray fur. And then she leaned her head against the wolf's side. All through the night she was kept warm. And she was rocked. Rocked by the heartbeat of the wolf.

When morning broke, cold and blue, Tessie heard voices calling. "Tessie! Tessie!" The wolf leapt up, shaking snow off its back.

"Here I am! Father! Mother!"

The wolf scampered off, soon invisible in the bushes. Her mother and father rushed into the clearing. "Tessie?"

"Here I am."

"Oh, child, you're still alive! What a miracle!"

"It was the beautiful dog, the one you called a wolf, daddy!"

The parents looked at each other, bewildered, and they looked back at Tessie.

"The wolf was with me. The wolf kept me warm."

"Oh, she must have had strange dreams in the night."

"It wasn't a dream. The wolf ran away when you shouted but look there!" Tessie pointed to a track. A wolf trail, leading in the snow away from the tree where she had spent the night. Her father and mother stared.

"That was the wolf I nearly shot last week, and Tessie saved its life. Well I guess it came back to save your life, Tessie."

Now Tessie lived to be an old woman. And she told her story to her children and grandchildren, for she never forgot that Christmas Eve when she was kept warm, against that bitter storm, and rocked to sleep by the heartbeat of a wolf. (6:43)

CURWOOD: Our guest is Lee Ellen Marvin, a student and teacher of folklore. Stories are wonderful things to hear in the wintertime; I have to confess it's a long time since I walked into a family gathering where people were sitting around listening to a story. It seems like perhaps many of us have forgotten how to do this. What do you suppose we can do to bring storytelling back into our lives, back into our homes, especially at this season?

MARVIN: Well, there's a wonderful book on storytelling how-to, called Creative Storytelling With and For Children, by Jack McGuire. But even more basic, the thing to do might be to go to the librarian in the children's section of your local public library and ask about collections of Christmas stories, or collections of folk tales. And the basic steps to telling a story is, find a story you really love, not just sort of think it's all right, but you've got to love the story in order to work with it. Write an outline of the parts of the story, as few words as possible on one piece of paper. Put the book aside. And spend some time thinking about the events in the story to build up the images. The sights, the sounds, the smells, the textures, the tastes even. And the personal feelings of the characters in the story. Until the story feels as if you had once dreamed it or maybe experienced it years and years ago. And from there, you put it into your own words. And very quickly you'll find that you don't have to struggle to memorize a story. Memory is never a problem once you've got those images in place. And each time you tell the story the words will come out different. And that's appropriate. And that's the basic tool of storytelling.

CURWOOD: All right. I think I'll try it.

MARVIN: Good.

CURWOOD: Our guest has been Lee Ellen Marvin. She's a storyteller based in Philadelphia and a PhD candidate, by the way, in the Department of Folklore at the University of Pennsylvania. Thank you so much for joining us.

MARVIN: Thank you for having me.

Related link:

Lee-Ellen Marvin now works in the Suicide Prevention Crisis Service in Ithaca, New York

Storyteller Lee Ellen Marvin with some ideas for how to master the art of weaving tales to tell the company gathered round the fire on winter evenings, that’s if they aren’t all busy with their computers and on-line games!

When she isn’t spinning yarns herself, Lee Ellen teaches at Ithaca College in upstate New York.

Coming up --Native American tales that help explain why things in the universe are the way they are –

ROSS: And so they organized a search party to go in search of Bear. Now, Fox was chosen for his cunning, and Wolverine and Bobcat and Wolf for their fierceness and their strength. And those 4 were getting ready to walk out of the council when they heard a little voice speaking up. And they looked and it was the little Mouse. Well, the bigger, stronger animals didn't see how Mouse could be any help, but they decided she should go. :24

Of course – you guessed it – it’s Mouse that makes their search succeed – to find out how keep listening to Living on Earth!

Native American Tales

.jpg)

Stories of the seasons (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Our gift to you this holiday season is an old-fashioned one: it's some stories. Not the latest news and environmental stories we usually tell, but the kind that people have told the world over for -- well, forever – full of the wisdom of the elders. They are about earth-keeping, how things came to be, and human relationships with other living things.

(Flute music up and under)

CURWOOD: That's the music of Medicine Story, a Wampanoag storyteller based in New Hampshire. (He's the author of 2 books: Return to Creation, and Children of the Morning Light. – actually now there’s another one – do we care about Ending Violent Crime: A vision of a society free of violence (a community building program tested and proven successful under the most adverse conditions), a report of a successful prison program, Story Stone Publishing (1996) ??) Welcome, and would you tell us that story of yours about the darkness of winter and welcoming the sun? (:45)

The deep snow of winter (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

STORY: Just about now we're having the longest nights of the year. And as of the solstice, which was the 21st, then the nights will start to get shorter again all the way until June. So we have a story to explain about that, and it explains a lot of other things, too. It's about a time when the sun didn't turn around and start to come back, but the days just kept getting shorter and shorter and shorter. And eventually they were so short that well, people would be jumping up as soon as they saw the sun come into the village. They'd jump into their clothes and run out, and the sun would already be going down and that was the end of their day. And they were very worried, because they said how are we going to grow our three sisters, the corn, beans, and squash? How are we going to go hunting and do our fishing, get our livelihood here if it's dark all the time?

Well when they spoke to their helper, first teacher Moshap, he said well I'd better go talk to Grandfather Sun and see what's wrong. And of course where we live here now, on the East Coast in order to talk to the sun in the morning you've got to go out to sea, because it comes out from the ocean out there. So he waited way far out, close to the sun coming up place. And soon as the sun popped up, he began to address and say Grandfather, you know, people are very worried you're not here very much. It's certainly good to see you today. And they began to tell their story, but unfortunately he didn't get a chance to really get into it, because the sun dropped out of sight again and it was dark. He tried that three days.

A winter landscape (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

So at the end of that third try, he went down to the bottom of the ocean, began to pull out long strands of seaweed that grows way down there. And he tied them in knots and made a fish net, just as he had taught the people to make a fish net. And he made this net really big. It was a net big enough to catch the sun. And he stood out there the next time the sun was ready, and as soon as the light appeared he started swinging this net around. And he threw it just as the sun rose up, and right into the net the sun went. Moshap reached out, grabbed a-hold of the net and pulled it tight, and just held the sun right up in there.

Now the sun is struggling away, saying, "Who's doing this to me? Get this thing off of me! What's going on here?" And Moshap is holding on real tight out there, saying, "Well, I'm sorry, Grandfather, to have to do this to you. But 3 days I've been trying to talk to you and you wouldn't stop and listen. Now I'm going to hold on till you promise to listen to me." And the sun said "Oh well, all right. What is it?" And when he heard about what the people had said, he says, "You know, I think that's kind of funny, sort of peculiar, because I didn't think those people there even cared about me at all. You know, when I get there in the morning they're all asleep, and they don't even bother to come out and talk to me and thank me for that sunlight or anything. They never come to say goodbye when I go. So I just got to going shorter and shorter, because I like to spend my time on the other side of the world where there's people that really appreciate me."

Well, when the people heard that, they were pretty ashamed of themselves because they hadn't even considered the sun's feelings before. So the next time he came, people built a fire in the center of their village. And they were throwing tobacco in the fire, which is our way of giving thanks. Said "Thank you, Grandfather, for coming back, for giving us another day, another chance to live and learn." And all day long the people would look up and smile at him and tell him stories and gossip with him. And at the end of the day, they would gather up on the hill and all wave: "Bye, Grandfather, that was a great day you brought us! You hurry back and we'll be waiting for you!"

So the sun kind of liked that and he started to come back and the days got longer, and we got a chance to plant the corn, beans, and squash and go hunting and fishing and all that. But somewhere towards the end of June he was thinking, "Well, I kind of miss those other folks." And then he would begin to go back and spend more time over there, and our days would get shorter just as they do now. But he never, never went back to the way it was before, because we always tell this story. So it's a kind of a way of life that we have. We say all of our prayers, our prayers at Thanksgiving, because we've been given so much. (5:37)

CURWOOD: Medicine Story is a wonderful name, especially for a storyteller. How did you get that name?

STORY: Well, it happened many years ago, after I had found my way into the wisdom of the elders of this continent. Traveled all around the country and learned the old ways from the old people. And I got a vision that these old ways were not just for the Indian people, that this was human being ways that had been lost by other cultures. And that it was the responsibility that was given to us to be able to let people know about these ways. And when that happened I realized that this was a big change in my life and I was going to have to be doing different things. And usually, traditionally, when you have a change like that in your direction, well you may take on a new name. And I was at a ceremony, and I had told a lot of stories, and I had talked about this change and this new path. And so that's when they gave me this name, which in my language is Manintonquat. And it means "he's telling stories of the spirit." And so in English, Medicine Story is kind of a shorthand way of saying that. (7:06)

Story teller Manitonquat or Medicine Story with Ellika Linden (photo: circleway.org)

CURWOOD: Well, Medicine Story, I want to thank you for taking all this time with us. Medicine Story has 2 books. One's called Return to Creation; the other's called The Children of the Morning Light. Thanks for joining us.

STORY: As we say in our language, tabotny. Thank you.

(Flute music up and under) (@ 7:23)

CURWOOD: Have you ever wondered why winter can linger and linger? Gayle Ross is a Cherokee storyteller based in Fredericksburg, Texas, and joins us now from member station KUT in Austin. Gayle, you have a tale for us of an unbearably long winter. Could you tell it now?

ROSS: I'd be glad to. This story is called Keeping Warmth in a Bag. It comes from the Slavi people of Canada. The Slavi people are related culturally and linguistically to our Plains people; in fact, they're one of the northernmost tribes of the Plains culture.

It seemed that long, long ago, before there were people, winter came onto the land, and then never left. The sky was hidden with these big black clouds; it snowed all the time. This went on for about 3 years, and the animal people were freezing and starving, and so they all came together in a great council. (:21 :14)

Now after talking about it for a long time, they all agreed that spring could not come because there was no warmth in the world. Someone had taken all the warmth. And finally someone spoke up in council and they said you know, this must be hardest on our sister the bear. She has always hated the cold. Someone ask Bear if she will come and talk to us and tell us how she is doing. So all through the council people began calling for Bear, and when she did not answer, that was when they realized she was not at the council. And they realized that no one had even seen the bear since the snow and ice had started. And one wise one said well, maybe Bear has something to do with our trouble. We should go find her and find out. (9:16)

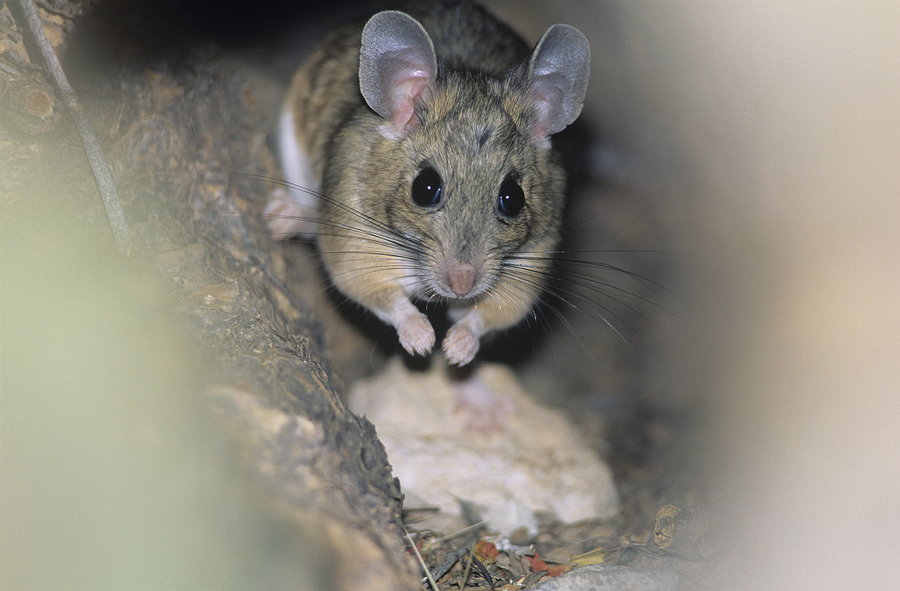

And so they organized a search party to go in search of Bear. Now, Fox was chosen for his cunning, and Wolverine and Bobcat and Wolf for their fierceness and their strength. And those 4 were getting ready to walk out of the council when they heard a little voice speaking up. And they looked and it was the little Mouse. Well, the bigger, stronger animals didn't see how Mouse could be any help, but they decided she should go.

A mouse in the woodlands (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

Now they searched all through this lower world. But nowhere could they find Bear. And finally they came to a great tree that lived on the Earth at that time. Its uppermost branches rested all the way against the sky and at the top branch there was an opening to the upper world. Now, none of these animals had ever been to the upper world, and they were very frightened. But Bear was nowhere in the lower world, so they thought that that must be where she had gone. So they climbed that great tree, and they squeezed through that opening in the top. And they set out to search in the upper world.

Now the first thing they noticed was that it was not snowing in the upper world, and the air was much warmer. And so they thought they might be on the right track. They wandered through the upper world until they came to a lake. And on the shores of that lake, there was a little hut there, and there were 2 little baby bear cubs playing in front of that hut.

So the animals walked up to the baby bear cubs, and they greeted them. They said, "Where is your mother?" And the bear cubs said, "She is out hunting." And they pointed across the lake. And sure enough on the other side of the lake there was a canoe beached there. Well. "We'll come in and visit with you," said Fox. "We're old friends of your mother's and we have traveled a long way to be here with you." So the little cubs led them inside the hut. And the first thing they noticed was these 4 big leather bags hanging from the poles that made the roof of the hut.

Fox pointed to those bags and said, "Now -- what are in those bags?"

"Oh -- mother keeps her treasures in there," said the cubs.

"What is in that first one?" said Fox.

"Oh, that is the one she keeps the spring rains in," said the cubs.

"Well what is in the second bag?" said the Wolverine.

"Oh, that is where the summer winds live," said the bear cubs.

Wolverine said, "And what is in that other bag? That third bag there?"

"Oh," said the bear cubs, "that's where she keeps the fogs and the mists of fall."

Then Fox pointed to the biggest bag of all and he said, "And what does she keep in that bag?"

"Oh, we can't tell you that," said the bear cubs. "Oh, that bag is the most important of all. Mother says without that bag, she couldn't keep any of the others. We cannot tell you what's in that bag." (12:07)

"Oh, but we are such good friends," said Fox. "And we have journeyed so far to be with you here. You can tell us. We are your friends."

"Oh," said the bear cubs, "Mother would beat us if we told you what's in that bag."

"Oh, but she won't know," said Fox. "We won't tell on you."

"Well, in that case," said the baby bear cubs, "that is where Mother keeps the warmth. All the warmth of the world is in that bag."

"Thank you little bears," said the Mouse. "You have told us all we needed to know." (12:40)

Now they went outside and they held a council. They decided they would hide until that mother bear returned. But first, the little mouse ran all the way around the lake, jumped in that canoe and nibbled on the handle of the paddle, until she had nibbled it almost through. She came back and she hid with the others, and when they saw that mother bear coming, the Bobcat, using his magic, changed himself into a caribou calf and appeared in front of that mother bear. The mother bear called to her babies, "You stay right there, I'm bringing you caribou for dinner!" The baby bears came out of the hut and said to the others, "What did she say?"

"Oh," said Fox, "she says she needs for you to come and help her hunt that caribou for dinner. It's a good thing you have good friends here who will guard those bags while you go help your mother." (13:34)

So the baby bear cubs ran off after their mother, and that bobcat caribou led them deep into the forest. The other animals hurried inside. Mouse skittered up the poles, ran out and began nibbling on the leather laces that held that bag, and that great big heavy bag holding all the warmth dropped. The other animals caught it. They dragged it outside. They looked up, they saw that bobcat caribou swimming toward them across the lake. They saw the mother bear and the babies hop in that canoe and begin paddling across that lake. But when they were in the deepest part of the lake, the paddle that Mouse had nibbled snapped, and mother bear was so surprised. She turned over that canoe and she and her babies began swimming to shore. (14:21)

Now Bobcat changed back into himself, and he and all the other animals, they began pulling that heavy bag back toward that opening from the upper world to the lower world. But oh, it was heavy! One would carry it for a while and then he would have to hand it off to another. And all the time, they could hear mother bear running and yelling at them to stop. They had just reached that opening in the sky and mother bear was almost on top of them, when Mouse nibbled a hole in the bottom of that bag; they pushed it through the opening. When Bear reached out to grab that bag, she squeezed it and all the warmth squeezed out into the air of the lower world.

Well, the ice and the snow melted. The sun shone again. The trees covered themselves with leaves and the new grass grew. And finally it was spring. Now the other animals, they talked very hard to mother bear. But it was agreed that since she hated the cold so much, they would let her sleep through the winter, and so she does. She enjoys the warmth of the summer, but when the leaves change and the cold comes, mother bear, she goes to sleep and she doesn't wake up again until the spring. 15:47)

CURWOOD: Well that's one naughty little bear. I suppose the story's really about greediness.

ROSS: Yeah, it's about throwing things out of balance. You know, you find examples of this kind of thinking in stories from people all across the continent. Joe Brushak tells a wonderful story about Gloo Scabby when he was young and foolish wanting to go duck hunting. And the wind was blowing so strong he couldn't paddle into the lake. And his response was to go and capture the wind eagle, the eagle whose wings bring the winds, and tie him up. And then he discovered what a terrible place the world was with no winds blowing. But you find those kinds of stories all over, where for one selfish reason or another, one person tries to control one aspect of the natural forces and it always succeeds in throwing the entire world out of balance. I don't think we always stop to think about the balance on the earth and just how delicate it is.

CURWOOD: What a great story. And what a great storyteller. Thank you so much, Gayle Ross, for taking this time.

ROSS: Thank you. (16:57) (ends @ 48:48 into the show)

(Music up and under: a Native American dance) (mux to 17:07, @ 48:57)

Related links:

- Gayle Ross’s Bio

- Medicine Story’s bio

CURWOOD: Coming up – How come the seven stars we call the Pleiades twinkle and seem to dance up there in the sky - That’s just ahead on Living on Earth – stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Stories of the Night Sky and an English Wassail

A clear winter night (photo: bigstockphoto.org)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Now, in many traditions including ours here at Living on Earth, winter is the season of storytelling. The cold invites us to put on the kettle, gather together, and spend some times just listening to stories. Here's an encore presentation that features New York storyteller, Joe Bruchac.

BRUCHAC: Long ago, the Iroquois people say there were 7 boys who wanted to do just as their fathers did. To have a special medicine lodge society. In such a lodge, they would play a drum and they would dance and sing and they would have a great feast afterward, and so they went to their parents and told them what they wanted to do. But their mothers and their fathers, they laughed at those boys: "You are too young to do this sort of thing! Go and play some other game that children play."

Those boys became very angry. They began to walk out of the village, and as they walked out, an old man was there near the edge of the village holding a drum. He said to them, "Here. You can have this drum." They took that drum, and they continued on until they reached a place on the other side of a hill and there began to dance and sing, louder and louder, so loud that the sound of their dancing and singing reached back to the village. And their mothers and fathers hearing it, said, "Who is having the meeting of a medicine lodge society? Who could that be?"

They followed the sound of the drum. They came to the hilltop and they looked down and they saw those 7 boys dancing in a circle, playing the drum and singing. But they were so angry that as they danced and sang, the power of their singing and dancing was such that their feet were no longer touching the ground. Higher and higher they danced, higher and higher. Their parents called out to them, but they continued to dance. Although it is said that one of the smallest ones looked back and fell down as a shooting star.

The others danced right up into the sky. They dance there to this day, those 7 dancing boys that are now called the Pleiades by European people. But those are those boys from long ago, whose parents did not respect them. (@2:02)

CURWOOD: Joe Bruchac, thanks for joining us on Living on Earth.

BRUCHAC: Mm hm. Thank you.

CURWOOD: You're a storyteller. You're a writer. You live in Greenfield Center, New York. That's in the foothills of the Adirondacks. And you’re a member the Abenaki Nation. But you also have roots in other traditions, too, right?

BRUCHAC: Yes, Slovak and English, that's also part of my ancestry.

CURWOOD: Well those all have some pretty strong oral traditions. And perhaps, not coincidentally, some long winters.

Joe Bruchac

BRUCHAC: Well, winter is the time for telling stories in many traditions, especially for the Native people of this continent. Because the days were very short and the nights were very long, it was a good time to tell stories. And you would need a good story to get you through those long nights. It's also true that the stories were not supposed to be told in the summer. For example, a good story is so powerful that everything wants to listen to it, including the snakes who are awake in the summer time. So if you don't want snakes in your house, you don't tell these traditional stories when the days are long. (@ 3:02)

CURWOOD: (Laughs) Okay. What gave you this bug? Why do you tell stories?

BRUCHAC: I was raised by my grandparents. And although my grandfather, who is Abenaki Indian, did not tell traditional stories, he ran a little general store and a gas station and people would come there and sit around the potbellied stove and trade tall tales. Usually from the Adirondack traditions. And I think if you grow up around elders and you listen, in a way you can't help but become a storyteller. (@ 3:29 – from here+ final mux for half hour)

CURWOOD: Anything else you want to tell us from your Native American tradition?

BRUCHAC: (starts at 3:34into Bruchac -- 2nd half hour story?) This is a story that again comes from the Iroquois people. The great midwinter ceremony takes place traditionally at the solstice time of the year, although nowadays it takes place in January. They've moved it so it doesn't compete with Christmas. And at that solstice time, when the 7 dancing stars are in the exact center of the sky, they play a game called the bowl game in which you put a number of stones, painted black on one side and white on the other, into the bowl, shake it, and depending on how they come up facing black or white, you either score a point or you fail.

The story goes that long ago, Grandmother Moon looked down on the Earth and was not happy with what she saw. She said, "Life on Earth must end." Now the good mind, who was always a defender of the people, he said to his grandmother, "Grandmother, is there no way we can prevent this from happening? She said to him, "I will tell you what. We will play the bowl game and the one who wins will decide whether or not life will continue."

So the good mind went to the chickadees. He said to them, "My friends, I want you to help me." And he told them what he needed. And they said, "Of course. You can borrow our heads, which are black on one side and white on the other, put them in the bowl, and we will do what we can." So when the good mind took the bowl and he shook it, the chickadees flew up, their heads flew up looking just like little black and white stones, singing in mid-air. They flew around and then they landed and gave him a perfect score.

So it was that he won, and life on Earth continues. And so it is to this day that in the middle of the winter, you could hear the chickadees singing and celebrating the continuance of life.

CURWOOD: I guess I'll never look at the chickadee the same way again. You know, Joe, one thing that always intrigues me about Native American stories is and those from other traditional cultures is the way that you see the natural world in sort of human terms. Anthropomorphic, I think, is the long word. That the elements, that animals and plants have human qualities. And that's very different from the way that we generally see things in the modern world.

BRUCHAC: Well, the thing about traditional stories is that they remind us everything is alive and deserving of respect. And those stories have on the one hand the purpose of entertainment, but the reason they entertain is so that the lessons they teach will come across that much stronger. So if animals and plants are seen as being the equal and just as important as human beings, we're teaching a lesson that we need for survival. That was how my ancestors see it, and that is how I still see it to this day.

CURWOOD: Joe, we're just about out of time, but I saw you brought your beautiful drum. Could you do something with that for us?

BRUCHAC: What I want to share with you is actually a tradition from the Abenaki people, a tradition that is still carried out to this day. At this time of year, the December solstice, it was the time when people went from house to house greeting each other. And what they would say when they greeted each other this time, what they would say was, "An halom mawi, casia palwea walang." Which means, "Forgive me for any wrong I may have done you in the past year." And that was then followed by a friendship song and a friendship dance bringing the people together, back into the circle of life, forgiveness and respect restored. So I want to share with you that traditional friendship song. And its translation is very simple. It basically says, "I like this, and I like that." And that idea of caring for the people and the living things around you is at the center of the friendship song.

(Beats drum) We gai waneaaaa, we gai waneaaa, we gai waneaaaa, we gai waneaaa...

CURWOOD: Joe Bruchac, thank you very much.

BRUCHAC: Wole wanea, thank you.

CURWOOD: Joe Bruchac is a storyteller from New York State. He's also the coauthor, with Michael Caduto, of Keepers of Life: Discovering Plants Through Native American Stories and Earth Activities for Children. (7:55)

(Music up and under: flute and bird twitterings)

CURWOOD: With us now in the studio is a horse goddess. Hello.

EDGECOMB: (Laughs) Neeeeeigh!

CURWOOD: Actually, this is Diana Edgecomb and she's a horse goddess and all kinds of things as she tells her stories. Thanks for joining us.

EDGECOMB: Hello. It's a pleasure to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: Well, you use stories to explore the human connection to the natural world, and our estrangement from nature. That's why we've invited you here to the show. Tell us about the story you're going to tell now.

EDGECOMB: This first story I would like to share is actually collected by Ruth Tong, and she collected it from a man in Pittminster in England. And it's a Wassail story. And within the story there is a tree spirit called the Apple Tree Man, which we don't encounter very often now. But the Apple Tree Man was always responsible for the fertility of the entire orchard, so you can see that the Apple Tree Man was very important.

CURWOOD: Oh, yes.

EDGECOMB: And in the old days, instead of just Wassailing each other and getting drunk, people would actually do something to ensure the fertility of the orchard. They would have Wassail traditions. And include the natural world.

CURWOOD: Okay, well I'm ready if you are.

EDGECOMB: (Laughs) Yes, I am.

(Harp music plays; women sing: "Wassail, Wassail, all over the town. Our toast, it is white and our ale it is brown. Our bowl, it is made of the white maple tree. With a Wassailing bowl we'll drink to thee. Drink to thee! Drink to thee! With a Wassailing bowl we'll drink to thee.)

Diane Edgecomb and accompanist Margot Chamberlain (Photo: Stephen Cicco)

EDGECOMB: This is a tale of a hard-working chap, eldest in a big family, see? And so, when his dad die, there weren't nothin' left for he. Youngest gets it all! And youngest do give bits and pieces to all his kith, but youngest don't like eldest. All he do give eldest is his dad's old donkey, and an ox that was so skinny it was pretty much gone to anatomy. And his grandfer's old tumble-down cottage with its two dree ancient old apple trees. Only problem is, cottage doesn't have any roof. Only problem is, apple trees don't bear no fruit. But eldest don't grumble. No, sets to work. And he cuts the grass along the lane and feeds it to donkey and donkey starts to fatten. And he rubs old ox with the herbs and says the words for healing. And ox do pick himself up and walk smart. And then the eldest do turn those two beasties out into the orchard. And then those old apple trees flourish a-marvel.

Well one day, into the orchard came the youngest, and he says, " 'Twill be Christmas Eve come tomorrow when all the beasts do talk at midnight. Now I've heard tell and you've heard tell that there's a treasure buried hereabouts. And I'm set. I'm going to ask your donkey where the treasure is buried, and he mustn't refuse to tell me the truth, not on Christmas Eve. Now eldest, you wake me up just afore midnight. I'll take a whole sixpence off your rent."

Come Christmas Eve, the eldest don't forget the animals. He gives old ox and donkey a bit extra. And he fixes a bit of holly in the stables. And then he takes his last mug of cider, and he warms it and mulls it by the fire. And when it's warm and inviting, he outs to the orchard to Wassail the old apple tree. (A flute plays.) (Sings:) "Old apple tree, we'll Wassail thee, and hoping thou wilt bear. The Lord shall know what we shall need to be merry another year. So grow well and so bear well and so merry let us be. That everybody lift up a cup (Laughs) here's health to the old apple tree!" And he takes and throws the last of the cider on the old apple tree. "Good health to you, old apple tree!" And the Apple Tree Man within the tree, he looks out and speaks to the chap. You take a look under this girt didicki root of ours."

So the eldest looks under that girt didicki root. And the hard earth moves aside like it's sand. And he finds a small box, and within it, golden coins.

"You take it, and hide it, and bide quiet about it. 'Tis yours and no one else's."

So eldest does just that. And when he's finished, it's almost midnight. And he goes to wake up his dear younger brother. Well his younger brother wakes up and he's all in a hurry, push. He rushes out in his nightshirt with his hair all every which way. And sure enough, when he gets to the stables, the donkey is a-talkin' to the ox: "You know this girt greedy fool? A-listenin' to us so unmannerly? He do what we should tell him where the treasure is."

"And that's where he's never gonna get it," say the ox. "For somebody have a-tooked it already."

And the two animals, in concert, lifted their tails.

(Harp music plays. Women sing: "Oh here's to the ox and to his right horn. Pray God send my master a good crop of corn. And a good crop of corn that may we all see. With a Wassailing bowl we'll drink to thee. Drink to thee! Drink to thee! With a Wassailing bowl we'll drink to thee.")

CURWOOD: Well, that was terrific! Thank you. Diane Edgecomb is our guest here. She's a storyteller. I love stories, of course being in radio. In the news business, even, we call it a story; it gets edited. I think it's an essential part of us as human beings to tell these stories. But you tell stories about nature. Why in particular stories about nature?

EDGECOMB: Well, I think storytelling is such a connecting medium, and it really was a way for me to bring children and other people into a different relationship to nature through story. I could teach children, you know, the names of different birds and animals and processes. And stories are really the smallest unit of meaning, too, so I could in a way try and get them to see new meanings in the natural world.

CURWOOD: But much of your repertoire actually is for adults.

EDGECOMB: Yes. I think that that's because I'm also trying to make links for myself. Once I grew up and stopped climbing trees and building forts and I felt this loss of connection. And I had a few experiences, I think, that made me realize that I could find a medium, which turned out to be storytelling, that I could use to reconnect myself, and that needed to be in an adult form through seasonal folktales.

CURWOOD: Seasonal folk tales. Now, Joe Bruchac has just told us that the winter time invites storytelling. You're saying that adults need stories to unfreeze us in some fashion?

EDGECOMB: Yes. And the Wassail bowl can unfreeze you, too. (Laughs). But yes, a sense of community is really established through that, because it's not just the storyteller creating the story. It's the entire group of people having these images live in their mind's eye.

CURWOOD: Diane Edgecomb, we have time for just one more story. Do you have one that you could tell us?

EDGECOMB: I would really love to tell this Cherokee myth. It's a beautiful one for this time of year, and when I'm driving down the highway and I see the poor trees with no leaves and I see a few evergreens, I think of this story and I hope other people will as well.

When the plants and the trees were first created, they were given a task: to stay awake for 7 days and 7 nights. Now the first day and night, all of the plants and trees stayed wide awake and the second night as well. But by the third night, and the dawning of the fourth day, many of the small plants and some of the trees were falling fast, fast asleep. Who would be able to stay awake for 7 days and 7 nights?

But on the seventh night, and the dawning of the eighth day, there stood the cedar, the pine, the spruce, and fir, the hemlock, the holly, and the laurel. "You have endured," a voice said, "and you shall be given a gift. All of the other plants and trees will lose their leaves and sleep the winter long, but you shall never lose your leaves. You will provide a shelter to the birds during the harshest winds, and you will remind the people that even during the darkest times something remains. You shall be evergreen."

CURWOOD: Thank you very much. Diane Edgecomb is a storyteller. Thanks for coming by with your accompanist, Margo Chamberlain. Thank you so much for joining us.

Diane Edgecomb

EDGECOMB: Thank you very much for bringing us here.

Related links:

- Joseph Bruchac’s website

- Read more about Diane Edgecomb at Living Myth

(Harp music up and under)

CURWOOD: And for this week that's Living on Earth. Kim Motylewski is our associate editor. Peter Thomson heads our Western Bureau. Chris Ballmann is our senior producer, and Liz Lempert directed our program this week. Our production team includes Jesse Wegman, Daniel Grossman, and George Homsy, Julia Madeson, Peter Christianson, Roberta de Avila, and Peter Shaw. We had help from Dana Campbell. The storytelling segments were recorded by Jane Pipik. Michael Aharon composed the theme. Eileen Bolinsky is our technical director. Jeff Martini engineers the program, which is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. I'm Steve Curwood, executive producer. Happy holidays, and thanks for listening.

(Harp music up an under)

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Kathryn Rodway, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of The Nation, where you can read such environmental writers as Wen Stevenson, Bill McKibben, Mark Hertsgaard and others at TheNation.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth