April 19, 2002

Air Date: April 19, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Superfund

View the page for this story

The Bush Administration is making some fundamental changes to the hazardous waste cleanup program known as Superfund. Living on Earth host Steve Curwood speaks with Democratic Senator Robert Toricelli of New Jersey about the changes, and his call to renew the Superfund tax on corporations. (06:10)

Biodiesel

/ Charlotte RennerView the page for this story

Biodiesel is a non-toxic, renewable fuel that can be used in diesel engines. The fuel is made from vegetable oil and creates less pollution than fossil fuels. But as Maine Public Radio’s Charlotte Renner reports, it might take some tax breaks, or other incentives, before biodiesel finds a broad audience. (06:30)

The Living on Earth Almanac

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about the right to ramble. Seventy years ago, working class Brits demanded the right to wander on private property. (01:30)

German Hens

/ Mike MühlbergerView the page for this story

More than three-quarters of all egg-laying hens in Germany are kept in cages. The government recently declared the farming practice in violation of animal protection laws and decided to ban all hen cages by 2012. Mike Mühlberger reports that many farmers fear the new law will harm their ability to make a living. (09:00)

Wilderness Commentary

/ Jeanne WilkinsonView the page for this story

Jeanne Wilkinson describes finding wilderness in her own neighborhood. (03:25)

Hornbill Feathers

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood talks with Christine Sheppard of the Bronx Zoo. She coordinates an innovative program that exports molted feathers from hornbills in U.S. zoos to Malaysia, where they can be used in traditional ceremonies. (03:00)

Health Note/Tick Saliva

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports that researchers are examining the ingredients of tick saliva to create a vaccine against Lyme disease. (01:20)

Listener Letters

View the page for this story

This week, we dip into the Living on Earth mailbag to hear what listeners have to say. (02:30)

Monarch Butterflies

/ Brian MannView the page for this story

North Country Radio’s Brian Mann takes us on a journey to Central Mexico to the monarch butterfly’s wintering ground. The butterfly’s habitat is endangered by logging and farming, but a unique program is trying to help residents make a living by preserving the monarch’s habitat. (11:50)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

REPORTERS: Charlotte Renner, Mike Mühlberger, Brian Mann

GUESTS: Robert Toricelli, Christine Sheppard

COMMENTATORS: Jeanne Wilkinson

UPDATES: Diane Toomey

[INTRO THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From National Public Radio, it's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. As the Bush administration reduces the number of Superfund sites marked for cleanup this year, a Senate Democrat calls for renewal of the tax on corporations.

TORICELLI: We took a nation that was littered with chemical and petrochemical pollution, and built a multibillion-dollar fund to clean scores of these sites. We did it. We did it well. We should be proud of it. Now we need to get it finished and we've allowed it to expire. It doesn't make any sense. This is an American success story.

CURWOOD: The fight over the Superfund on Capitol Hill. Also, a sanctuary in central Mexico for migrating monarch butterflies is in danger.

BROWER: This thing is a treasure comparable to the Mona Lisa or the Chartres Cathedral windows or Mozart's music.

CURWOOD: A new program may make a difference. We'll have those stories this week on Living on Earth coming up right after this.

[THEME MUSIC]

[NPR News]

Superfund

CURWOOD: The White House also announced that it does not favor the renewal of a tax that will make industries pay for the cleanup of abandoned sites where there is not an identified responsible party. Instead, the money would come from the general treasury or taxpayers pockets.

Senator Robert Toricelli is a Democrat from New Jersey. His state harbors the most Superfund sites in the country and he's been pushing to reinstate the Superfund industry tax. He joins me now. Senator, welcome.

TORICELLI: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: We invited the White House to appear on the program. They declined. But they argue that one of the main criticisms of the Superfund tax was that 70 percent of Superfund cleanup is already paid for by identified responsible parties, and that the tax forces corporations to pay additionally for sites that they aren't responsible for, and that, really, it's not truly a ‘polluter pays’ tax. Why should an innocent corporation pay for this cleanup?

TORICELLI: Well, the sites have to be cleaned. And there are several ways to do this. Where the Environmental Protection Agency can identify the responsible party, then appropriately, that party pays for the cleanup. In those cases where no one can be found, that is left to the taxpayers.

Well, there're two sets of taxpayers. There are American families who pay their income taxes that never profited from the production of these materials, bear no responsibility for these materials, only have the health consequences of these materials. Or, there are corporations themselves.

Now, we may not be able to find the individual corporation responsible. But I think it is fair to have a very small tax on all corporate activity that is, in some way, related to the chemical or petrochemical industry, rather than asking middle-income families to pay this out of the their income taxes.

CURWOOD: The Bush administration is cutting the number of Superfund sites that they're going to cleanup, what, by half Senator? Now, the argument they advance is that, look, in the past, the Superfund tax was used to cleanup rather simple sites. And, now that the program has reached a point of getting down to some of the more difficult places, it needs to deal with bigger and more complicated sites that take more time and money, and that the number of sites, the raw number of individual sites, really isn't a good measure here. How fair is that argument?

TORICELLI: Actually, I think that argument has some merit, that there are larger sites. The easier ones have been done. And I don't want to be unfair to the administration. I think they make a good point. It does, however, have a regional overlay that causes some difficulty, in that the more complicated and larger sites tend to be in the west and very rural areas. The smaller sites, that could be dealt with more easily, tend to be in very populated areas.

So, for example, the delays that we're looking at in coming years, New Jersey has 59 sites that would be delayed under this administration strategy. New York has 40. Pennsylvania, 31. Illinois, 17. You can see where the concentration would be, of these sites that they're moving away from. And as the most densely populated state in the nation, not only do we have the most Superfund sites, but we have more people living in direct proximity to those sites. It's a dangerous combination that should enter into their prioritizing.

CURWOOD: How do politics enter into this? New Jersey takes the biggest hit under the administration's plans to scale back Superfund, as you say. What do you think is the calculus here?

TORICELLI: I don't want to be cynical about it. But the reformulating to deal with the larger, so-called more complicated sites in the west, obviously also overlays nicely with the electoral map of the United States in presidential politics. And I certainly don't blame the Bush administration for looking after their own electoral constituency most directly. But I'm sure they can understand my responsibility to make sure the people of New Jersey are protected. And I'm not going to see these resources either dwindle or, just as importantly, what resources remain, go to other places in the country that are less populated, and away from New Jersey. We simply serve differently masters if that's the calculation.

CURWOOD: What are the two or three examples in New Jersey that come to mind?

TORICELLI: Almost every county in my state has an example of this. We, of course, have a very large petrochemical industry. Standard Oil was created in New Jersey. In the county where I live, in Bergen County, we actually have what are some radioactive locations, some of these going back to the war. A small community in Maywood, New Jersey, in the First World War, they manufactured lanterns for trench warfare. Well the radium that was used in those lanterns remained in the ground. And here we are 90 years later, it all needs to be removed. The company is hard to locate. It's very difficult to find legal responsibility. But, the people who live in those houses want to know that their front yards do not have radioactive materials in them. I could cite an example like that in 50 communities all around New Jersey.

CURWOOD: What's the future of the cleanup of Superfund sites?

TORICELLI: What is curious about opposition to my efforts to continue the Superfund is that this is, perhaps, the most remarkably successful environmental program in history. We took a nation that was littered with chemical and petrochemical pollution, inexplicable health problems in surrounding communities, built a multi-billion dollar fund, largely paid for by the people most directly involved in producing these materials, with little burden on the American taxpayers. We created companies, and governmental capabilities, to clean scores of these sites. We did it. We did it well. We should be proud of it. Now we need to get it finished and we're allowing it to expire. It doesn't make any sense. This is an American success story.

CURWOOD: United States Senator Robert Toricelli is a Democrat from New Jersey. Thanks so much for taking this time with us today.

TORICELLI: Thank you for having me.

[MUSIC: Steve Roden, “Saint Francis’ Vision of the Musicial Angel,” IN BETWEEN NOISE (Inverted Tree Projects – 1993)]

Biodiesel

CURWOOD: In 1893, when Rudolf Diesel invented the engine that bears his name, he envisioned a fuel made from vegetable oil. The German inventor hoped to replace what was then the dominant power source for mechanized transportation, coal-fired steam. When cheap petroleum hit the market in the early 20th century, so-called biodiesel took a distant backseat. Supporters of this non-toxic renewable fuel are hoping to bring it back in the forefront as air quality standards kick in over the next several years. But as Maine Public Radio’s Charlotte Renner reports, right now, it's a lot easier to make biodiesel than to sell it at a profit.

RENNER: Biodiesel has been used extensively in Europe for over 20 years. But in the United States, it's still a rare commodity at the pump. So Peter Arnold, an environmental educator in Wiscasset, Maine makes his own.

[SOUND OF MACHINERY]

(Photo courtesy the Chewonki Foundation)

RENNER: Three days a week he takes his sky-blue pickup truck to the Sea Basket restaurant along Route 1. He uses a hydraulic hoist to unload two empty barrels and to pick up two 55 drums of used frying oil left for him outside the restaurant.

ARNOLD: If we were picking up a lot more oil, we'd probably have to figure out a different way to do it. But at this scale, it's just the right way to do it.

RENNER: Arnold takes the oil back to the Chewonki Foundation, an organization devoted to environmental education. Chewonki uses the biodiesel fuel to heat its buildings and power its tractors. It also uses it as a teaching tool. In a corrugated steel shed, Arnold has rigged up a small biofuel demonstration factory.

ARNOLD: Let's go in and I'll tell you how to make it.

RENNER: Arnold leads the group of 12 high school students to a large contraption, a 275 gallon storage tank sitting on a six foot high platform. A rubber hose runs from it to another tank on the floor.

ARNOLD: So it isn't very elegant. But it changes vegetable oil into a biofuel.

RENNER: The sump pump propels the fryolator oil from the oil drum taken off Arnold's truck upwards to a reaction tank where it mixes with methanol and lye, a catalyst. Arnold heats the mixture to 120 degrees, stirs, and lets it settle for eight hours. As it cools, glycerin, a byproduct, settles to the bottom, and gets siphoned off. And, the distilled fuel drains into the barrel on the ground, ready to be tapped.

Biodiesel can be used in any vehicle that runs on petroleum diesel, including Arnold's Volvo station wagon. As Arnold turns the ignition key, the grayish exhaust becomes an almost transparent mist curling out of the tailpipe.

[SOUND OF CAR STARTING]

ARNOLD: There's no sulfur in vegetable oil. So there's no sulfur dioxide formed. Sulfur dioxide is the precursor of acid rain. So we've cleaned up now. We've got nice, clean exhaust. It smells like French-fries. That's cool. And we made it ourselves. That's even cooler. Yaaay!

[CLAPPING AND CHEERING]

RENNER: But after the cheering stops, even these environmentally conscious students will hop into cars powered by gasoline. They all know that low sulfur biodiesel is kinder to car engines and creates less air pollution than fossil fuels. And they know that biodiesel spills are nontoxic. But they also know they'll have trouble finding the alternative fuel at a price they can afford.

These days, American drivers are paying anywhere between $1.20 to $1.40 a gallon for gasoline. Biodiesel runs anywhere from $1.90 to $3.00 a gallon. But some drivers are willing to pay a little more to keep their consciences, and their engines, running cleaner. John Wathen, who commutes 80 miles a day for his job in Maine's Department of Environmental Protection, mixes the vegetable derivative with regular diesel to keep the biodiesel from gelling in cold weather.

WATHEN: At 40 percent, which is a nice blend for much of the year, it costs me about another penny a mile to drive, which I'm good for a penny a mile. And at 20 percent, it's really only about 10 or 15 cents more a gallon in your total fuel than pure diesel is. So, it's really not a big consideration.

[SOUND OF MARKET]

(Photo courtesy the Chewonki Foundation)

RENNER: To feed his tank, Wathen takes weekly trips to the Solar Market in Arundel, Maine where he fills his five gallon jugs from a 10,000 gallon storage cylinder. Like about a dozen other customers, Wathen pays for 500 gallons in advance, at $1.96 per gallon, and records his withdrawals on the honor system, in a well-worn black binder.

Solar Market owner, Noato Inoye, buys the soybean-based fuel from a Boston wholesaler who gets it from Illinois. Inoye sells it at cost, or at a loss, to bring in customers. But he's convinced biodiesel will slowly win converts, and may even spur some local farmers to grow soybeans or rapeseed and turn that oil into cash.

INOYE: The biodiesel production is going to be a regional enterprise. It really doesn't make any sense to begin transporting biodiesel that was created in Texas to sell it in Maine.

RENNER: Biodiesel is being used in several Midwestern and Southern bus and truck fleets, and transit systems and on the island of Maui. And in Minnesota, the nation's largest soybean producer, a new law passed last month will require that two percent of the state's diesel pool includes soybean-based biodiesel.

Christopher Flavin, president of the environmental advocacy group, Worldwatch, says it will take measures like that, plus tax incentives for producers and users, to bring biofuel out of French fryers and soybean fields and onto the highways.

FLAVIN: Whether you're talking about ethanol or biodiesel or natural gas or hydrogen, and these are all very serious alternatives that are out there today, I think they're all going to require some degree of financial incentive in order to get a start in the market.

RENNER: Flavin says that more people, himself included, would try alternative fuels like biodiesel if they were readily available. For Living on Earth, I'm Charlotte Renner in Portland, Maine.

CURWOOD: Coming up, Germany moves to ban the factory farming of chickens in cages. You're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Hooverphonic, “Inhaler,” STEREOPHONIC SOUNDS (Sony – 1996)]

Related link:

The National Biodiesel Board

The Chewonki Foundation">

The Living on Earth Almanac

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: B-52s, “Roam,” COSMIC THING (Warner Bros. – 1989)]

CURWOOD: The right to ramble across Great Britain has not always been self-evident. Seventy years ago, an angry mob in northwestern England descended on a plateau reserved for wealthy grouse hunters. The working-class walkers demanded the right to wander anywhere they pleased. Joan Long is with the Rambler's Association in North Devon.

LONG: People that worked in the factories realized how much land that they couldn't go and enjoy. So they decided they would walk across the countryside.

CURWOOD: What came to be known as the Kinder Scout Mass Trespass soon turned ugly. Police showed up to keep the plateau rambler-free. They imprisoned five people. Seven decades later, space to meander is still at a premium in Great Britain. In England and Wales, less than one percent of the people own two-thirds of all rural land.

This week, ramblers in Britain are reenacting the Mass Trespass. This time, the law is on their side. Parliament has passed a new measure that opens 4,000 square miles of private land for foot travel by 2005.

While ramblers are celebrating, some landowners aren't exactly overjoyed. Some who have put walls and fences up are finding their land recategorized as “open to anyone.” One farmer found a provision in the new law that exempts cultivated land. So, he started madly plowing up his moor, just to keep those pesky ramblers away.

Some landholders are pushing for repeal of rambler rights. But, for now, the law of the land gives UK ramblers the right to roam. And for this week, that's the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC UNDER]

German Hens

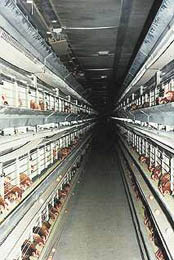

CURWOOD: The McDonald's fast food chain has just released its Social Responsibility Report. Among other things, the firm says it's committed to improving animal welfare. For example, McDonald's says that, since the beginning of the year, it has required more humane treatment of egg-laying chickens.

At many farms, chickens are stuffed into cages so crowed that the birds have trouble even turning around. But, McDonald's suppliers now have to reduce the number of chickens per cage. And if those firms were operating in Germany, thanks to a new law, they'd have to phase out all hen cages by the year 2012.

But as Mike Mühlberger reports, not all Germans support the new law. Many German egg farmers fear the ban on cages will put them out of business.

[SOUND OF GERMAN FOLK MUSIC]

MUHLBERGER: Farmer Alfred Huber knows how to entertain his guests. With folk music, beer and sausages, he's drawn hundreds of visitors to his annual farm festival near Düsseldorf. It's a great turnout, considering the terrible publicity German farmers have had in the past year. First there was mad cow disease, the biggest farming scandal ever in Germany. And now farmers like Huber are being accused of cruelty to hens. Just a day before this farm festival, the Green Agriculture and Consumer Protection minister, Renate Künast, persuaded Parliament to ban the 40-year-old practice of keeping laying hens in narrow metal cages.

[KUNAST SPEAKING GERMAN]

VOICEOVER: The will of German consumers is clear. They want farming to go hand in hand with animal rights and environmental protection. Keeping laying hens in cages has become a powerful symbol of an industrialized agriculture, which only aims to increase productivity with no regard for animals or the environment.

MUHLBERGER: The new law means that German farmers must phase out all cages for laying hens by 2012. Germany is going a step further than the European Union, which is also banning the conventional cages but will continue to allow slightly larger so-called “modified cages.” Most chicken farmers in Germany don't want the public to see how laying hens are kept. TV crews are still regularly denied access to barns. Alfred Huber is an exception. He wants to show his guests why he thinks the new German law is wrong.

[SOUNDS OF CHICKENS]

(Photo: www.vier-pfoten.de)

MUHLBERGER: Walking down a narrow aisle about 100 yards long, we're surrounded by 9,000 hens stacked in six rows of cages. Little conveyor belts bring their feed and take away their eggs. Huber opens a cage and pulls out a hen to illustrate the practical advantage of keeping them in cages.

[HUBER SPEAKING GERMAN]

VOICEOVER: You see this? Their feet are clean. The big advantage is that the hens have no contact with their feces. It falls through onto these conveyor belts which run under the cages. So the hygiene is excellent here.

MUHLBERGER: But animal rights groups disagree. They complain that farmers are torturing their animals by putting five hens to a cage, with less space per animal than an 8 1/2-by-11 sheet of paper. Still, Huber firmly believes he's not harming his hens.

[HUBER SPEAKING GERMAN]

VOICEOVER: Yes, it is quite narrow. You know, I used to ask myself, “Are we torturing the hens?” First I said, “I don't know. I've never been a hen.” But then I watched them, and decided, “No.” They experience real joy. I know it from the sound they make every time the feed belt starts up. They signal wellbeing. Yes, wellbeing.

MUHLBERGER: However, scientific evidence suggests that Huber is misinterpreting the sounds of his hens. The EU Scientific Veterinary Committee found that caged hens suffer intensely and continuously. Cannibalism, heart attacks and broken bones are just a few of the symptoms scientists have linked to the cages. They say caged hens are not only inhibited in their movement, but in virtually all other aspects of hen behavior.

Huber is one of seven farmers in Germany who received government funding two years ago under the old agriculture minister to test the new, slightly larger cages. They make provisions for three types of hen activity: perching, sand bathing and laying eggs in a nest. Huber is furious that even the new cages will be phased out by 2012. Dr. Astrid Funke of the German Society for Animal Protection says the new, modified cages simply cause modified suffering.

[FUNKE SPEAKING GERMAN]

VOICEOVER: In the new cages, hens have 300 square centimeters more space than in the old ones. That's about the size of three dollar bills. And the modifications have a mere alibi function. Cannibalism, for example, increases. That's because the hens have more room to attack each other, but not enough to escape. Basically, a cage is a cage.

[SOUNDS OF CHICKENS CLUCKING]

MUHLBERGER: In a field next to his barn, Huber also keeps free-range hens. They look and sound a lot more at ease. Huber admits there is a market for free-range eggs. But he says, it's too small and adds that it would be impossible to keep all the hens currently held in cages in fields like this. He says it would lead to an outbreak of diseases last seen in medieval times.

But Dr. Astrid Funke feels he's misleading his guests. She says the government isn't suggesting keeping large groups of hens in fields. The main alternative they want to encourage is barn floor housing. It's more labor-intensive, but if managed correctly, she says, hygiene isn't a problem.

[FUNKE SPEAKING GERMAN]

VOICEOVER: It certainly isn't a relapse into the dark ages when ethical norms are enforced. On the contrary, we already have good results in barn housing. The hens can move freely, and the floor can be cleaned. Our experience is that barn hens are five percent less likely to become ill than cage hens. And even their productivity is eight percent higher.

[SOUND OF BUSY FARM SHOP]

MUHLBERGER: Although 90 percent of German consumers say they're against caged hens, less than 30 percent of fresh eggs sold in Germany are from free-range or barn hens. Even in Huber's farm shop, most customers pick the cage eggs. Whether it's because they agree with his arguments, or because the cage eggs are about 20 percent cheaper, is hard to tell. The only visitors who don't mind being asked about their shopping habits are those who choose the free-range eggs.

[WOMAN SPEAKING GERMAN]

VOICEOVER: They taste better, at least I think they do. And I think it's also better for the animals.

[MAN SPEAKING GERMAN]

VOICEOVER: It's right to take a stand on this, even if the rest of the world doesn't follow us. We forget food scandals too quickly. I think we, the consumers, are to blame.

(Photo: www.vier-pfoten.de)

MUHLBERGER: Many German farmers fear that the total cage ban here will only help their competitors, especially in Eastern Europe, but also in the U.S. and Canada. In a study commissioned by the German Poultry Association, Professor Hans-Wilhelm Windhorst, an agricultural expert at the University of Vechta, predicts that as cages are phased out, foreign egg imports to Germany will more than double over the next six years.

[WINDHORST SPEAKING GERMAN]

VOICEOVER: We found that by going it alone, the domestic market share of German farmers will fall from currently 74 percent to 35 percent. We will also lose 4300 jobs. German hens will be better off. But we'll be importing large numbers of eggs from the EU and other countries where conditions are worse.

MUHLBERGER: He says many large egg farms will simply close up in Germany, and move to Eastern Europe and that small farms will go bust. But farmer Huber has no plans to leave. He can only hope that German consumers will prove him wrong, and start to pay more for their eggs. It's not like they don't have the money. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, a German worker's average hourly wage would buy only 5.8 eggs in the 1950s, whereas today, it will buy 136 eggs.

Agriculture Minister Renate Künast is optimistic that by introducing more transparent labeling and raising public awareness over animal welfare in farming German eggs won't stay on the shelf.

[KUNAST SPEAKING GERMAN]

VOICEOVER: We basically need to redefine quality in agriculture. In the past, the famous slogan, “Made in Germany,” has stood for quality engineering. With a booming food market, why can't this slogan, in the future, also stand for quality barn-floor and free-range eggs?

MUHLBERGER: For Living on Earth, I'm Michael Mühlberger in Düsseldorf, Germany.

[KUNAST SPEAKING GERMAN]

Wilderness Commentary

CURWOOD: The word “wilderness” usually conjures up images of untouched forests or remote mountain peaks. But as commentator Jeanne Wilkinson tells us sometimes you find wilderness where you least expect it.

WILKINSON: In the late sixties, I left the city to go back to the land, to do my part, to save the world through organic farming. But idealism doesn't carry too much weight on a dairy farm. Instead, you need an inexhaustible supply of money, time, patience and faith. When my favorite heifer, eight months pregnant, was struck dead by lightening, well that was it. In the eighties, I said goodbye to my sixties dream, applied for student loans, and went back to college.

I didn't have far to go. There was a university in a town only 25 miles away. I'd been there many times. But moving, uprooting myself and my two sons, that was hard. I missed the country, its million smells, and shades of green, its sky unbound by angles and roofs. So I hopped on my Goodwill bike and rode around town looking for green places to blunt the edges of this new life.

One place I found wasn't new to me. I'd seen it before when it was three blocks of army-issue Quonset huts, transformed into housing for married students. I'd drive in from the farm and stop by to visit a friend who used to live there. Her tiny round home was pleasant and cozy. Pretty pink roses bloomed outside her door.

But when I came exploring on my bike, the metal huts were gone, torn down. Where people had washed dishes and made love and yelled at each other, only bare concrete was left. Front stairways stood leading to nowhere. Roses bloomed in the yard, oblivious to the fact that their tender had abandoned them. Yard grass, once clipped short and neat, now grew long and silky as a young girl's hair. The people were gone. Nature had moved in, and I had found an accidental wilderness.

Every year, its domesticated past was harder to trace. More floors cracked and crumbled. More squirrels chattered. More birds sang. Roses, now hemmed in by wild blackberry vines, barely squeezed out a ragged bloom. Strange and spiky plants snaked around old shower drains. Fragile stalks pierced through asphalt and concrete. Nature, fierce and free, was taking over the place.

But now the sleepy college town turns into a city as Wal-Marts and suburbs sprout out of old farm fields. Last summer may have been my last visit to the accidental wilderness. The “No Trespassing” signs were new and shiny, instead of bent and rusty. I fear there are plans for the accidental wilderness, big plans. But if you know what's in store for it, please don't tell me. I'd rather remember it like it was, exuberant and growing. And sometime, somewhere, I'll find another one, another place that has, through some miraculous lack of human initiative, become an accidental wilderness, too.

[MUSIC: Denali, “Prozac,” DENALI (Jade Tree – 2002)]

CURWOOD: Jeanne Wilkinson used to be a dairy farmer in West Central Wisconsin. She's now an artist and freelance writer living in Brooklyn, New York.

[MUSIC UNDER]

Hornbill Feathers

CURWOOD: You're listening to NPR's Living on Earth. In Southeast Asia, the Rhinoceros Hornbill is often killed for its feathers used in traditional ceremonies. Scientists at the Wildlife Conservation Society came up with a novel solution to help halt the decline of this rare bird. Why not use the feathers that fall from captive birds in zoos? Christine Sheppard leads this effort from the Bronx Zoo.

Dr. Sheppard, how did you come up with this idea?

SHEPPARD: Well, I'd known for a long time that the federal government has a repository of bald eagle and golden eagle feathers that are made available to Native Americans for ceremonial purposes. And someone I work with, Dr. Elizabeth Bennett, who's been part of the Malaysia Wildlife Service for about 20 years, became very concerned, about five years ago, the increase in eco-tourism was causing an increase in native dance performances. And one of the popular dances was one that was done with Hornbill feathers. Each of the dancers has a fan of these feathers on each hand so that the hands represent wings. And the dance represents the birds in flight.

Malaysian dancer with Hornbill feather adornment.

(Photo: Elizabeth L. Bennett)

They only use the central tail feathers. So, it's only a few feathers from any bird, which is why it makes much more sense to get a crop of feathers every year from a bird that is sort of done with them, than it does to shoot a bird, which can never produce another set of feathers.

CURWOOD: Can you describe these Hornbills for me? What do these feathers look like?

SHEPPARD: Well they're basically black and white. They're maybe, I don't know, 18 inches long. They have a pretty squared off tail. And, if you think of the tail as being all white with a black band across the middle, that's what they look like.

CURWOOD: So, what was the response when you started calling around to various zoos that have Hornbills?

SHEPPARD: Every single zoo that has these Hornbills was extremely excited about becoming part of this program. Because we are always looking for ways that we can support conservation of our animals in the field.

CURWOOD: I would think that part of the power of doing the dance, in an ancient society, would be from all the work that went into getting these feathers. How appropriate is it to use captive feathers for something like this?

SHEPPARD: Well, that's actually a very complicated question. The feathers that we're providing are really for real ceremonies. Dr. Bennett came up with what I think is an absolutely brilliant idea of providing white turkey feathers which people could die a black band across for basically performances for tourists.

Dr. Elizabeth Bennett (left) and Dr. Christine Sheppard with donated Hornbill feathers.

(Photo: Dennis DeMello, Wildlife Conservation Society)

And, she did discuss with the headmen of various villages whether or not they would find it inappropriate to use tail feathers that were brought in from birds that had been in the United States. And they were delighted, partly because, in many of the areas that we're talking about, the birds have basically disappeared because of hunting pressures. So, they did not seem to have any difficulty whatsoever. It's the bird itself that's important, not where it is.

[SOUND OF BIRD CALL]

CURWOOD: Christine Sheppard is a curator for ornithology at the Bronx-based Wildlife Conservation Society. Thanks for taking this time with us today.

SHEPPARD: It was great to be here.

Related link:

Interested in adopting a Hornbill breeding nest?">

Health Note/Tick Saliva

CURWOOD: Just ahead, your letters and comments. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey.

[THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: Tick saliva is complicated stuff. It contains more than 400 proteins designed to make it easier to suck blood from a human. Some of these proteins suppress pain response. Others increase blood flow to the area and even prevent the body's immune system from attacking the tick.

But researchers at the University of Rhode Island hope to use tick spit as the basis for a vaccine against tick-borne diseases, including Lyme disease. Here's how. A vaccine might be able to train your body's immune system to recognize certain molecules in tick saliva. For instance, a vaccine containing the proteins that inhibit pain response would train your immune system to disable those proteins. So when a tick bit, you'd feel the pinch, promptly remove the little arthropod, and protect yourself against Lyme disease. That's because it usually takes a full 24 hours for Lyme bacteria to travel from the tick's gut into its saliva.

Researchers are now in the process of screening saliva proteins for promising vaccine candidates. And how do you get saliva from a tick? You put one on a microscope slide, put its mouth into a capillary tube, and then administer one drop of a muscle relaxant onto its back. In about ten minutes, the tick begins to drool into the tube. That's this week's Health Update. I'm Diane Toomey.

[THEME MUSIC OUT]

CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Medeski, Martin & Wood, “Pappy Check,” UNINVISIBLE (Blue Note – 2002)]

Related link:

University of Rhode Island press release">

Listener Letters

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Monarch butterflies in peril. We'll look at a program that pays residents of central Mexico to protect butterfly habitat. But first:

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Time for comments from you, our listeners. Verlyn Klinkenborg's recent commentary about the wild horses of the American West prompted a number of responses, including this note from Kathleen Bauer. She listens to WBBA in West Lafayette, Indiana.

"Thank you for bringing the severe plight of America's wild horses to the attention of the public,” she writes. “These animals, born wild and free, deserve something much better than capture by the Bureau of Land Management. Really rankling is the fact that these animals are removed from public land, leased to ranchers at a minimal fee. Cattle and sheep destroy the grasslands, and make life for the horses, and native animals, extremely difficult, and yet they, never the ranchers, are penalized. The demise of the wild horses is another bitter era in this country's history."

Helen Tanguis, of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, also asked, “If these people are accepting the land, then what do they have to complain about? Whatever came of the saying, 'Don't look a gift horse in the mouth?’"

Cindy Westerman hears us on WSKG in Binghamton, New York. She left a message on our listener line about Tom Springer's commentary on dark night skies.

WESTERMAN: I just wanted to thank you 100 percent, just thank you for doing that. That was a wonderful thing to bring out. I am an amateur astronomer. I also like dark skies. And I just cannot stand the proliferation of these suburban lights, people with these spotlights, and all the lighting in malls. It's just such an important issue. I just was so glad to hear it brought up on Living on Earth. Light pollution is just as bad as any other kind of pollution.

CURWOOD: Our interview about the hidden dangers of cosmetics with “Drop Dead Gorgeous” author Kim Erickson got some listeners blood boiling. John Knox heard the interview on WMRA in Harrisonburg, Virginia. He writes, “I was dismayed when the interviewee suggested that use of natural products will be preferable to the use of lab synthesized substances. It is a very common misconception to assume that natural products are benign or even helpful, and that lab synthesized products are more likely to be dangerous."

Or as WBUR listener, Howard Karten of Boston, put in an email message, “Arsenic and asbestos are natural ingredients, too. Do you want them in your cosmetics?"

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: We want your comments on our listener line anytime at (800) 218-9988. That's (800) 218-9988. Or write to us at 8 Story Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138. Our email address is letters@loe.org. Once again, letters@loe.org. And, visit our web page at www.loe.org. That's www.loe.org. CDs, tapes and transcripts are $15.00.

[THEME MUSIC OUT]

Monarch Butterflies

CURWOOD: Monarch butterflies have begun their spring migration north from the mountains of central Mexico. But over the winter, an ice storm ravaged that country's monarch sanctuary. Tens of millions of butterflies died. Ice storms are nothing new. But scientists say logging, and subsistence farming have damaged the tree canopy that shelters the monarchs. A decade of environmental initiatives have failed to stop the tree cutting. Now the World Wildlife Fund and the Mexican government are spending millions of dollars in a new effort to reshape the local economy. They hope villagers in the area will come to rely on the monarchs for their livelihoods the way they now rely on logging. North Country Public Radio's Brian Mann has our story.

[SOUND OF HORSE CLOMPING]

MANN: Riding up through a forest of pine and oyamel fir, the first thing I notice is the cold. This is the tropics, central Mexico. But as the trail winds and kinks toward 11,000 feet, the air sharpens. Even at midday, the sunlight feels thin and fragile.

At the end of a tunnel of trees, I see a twist of color. It's like coming into a church when shadows give way to gold and stained glass. Only here, the colors are alive.

[SOUND OF BUTTERFLY WINGS]

(Photo: Lincoln P. Brower, Sweet Briar College)

MANN: A monarch butterfly lands on the sleeve of my jacket. This is El Cincua, a monarch sanctuary that sits above the village of Angangueo. The tree branches are heavy with thick clumps of butterflies. Orange and black wings coat the tree trunks. Each insect folds neatly against the next. If you live east of the Rocky Mountains, the monarchs visiting your garden this summer likely come from right here.

BROWER: This thing is a treasure comparable to the Mona Lisa or the Chartres Cathedral windows or Mozart's music.

MANN: That's Lincoln Brower. He's a gray-haired man, a professor from Sweet Briar College in Virginia. Brower is one of the world's top butterfly biologists. So when he looks at the swarm of colored wings, he sees beauty, but he also sees an intricate living mechanism.

Each fall, hundreds of millions of monarchs travel south, surfing on thermal winds. They migrate to escape the harsh northern winter. According to Brower, the butterflies camp out in these mountain valleys to save energy, conserving the fuel they need for the spring migration back north.

BROWER: They have to preserve those lipids for five to six months. And they do this by going up to super-high altitude, and it's cold up there. It keeps them basically in a refrigerator. But, because it's the tropics, it's a stable cold weather.

MANN: The temperature is stable in part because of the tree canopy that drapes overhead. But the region of Mexico that offers this perfect winter sanctuary is tiny, only about 60 square miles. It also happens to be one of the poorest places in North America.

[SOUND OF PEOPLE AND CHURCH BELL]

MANN: This is Angangueo. The village of 5,000 people huddles in a narrow valley just below El Cincua. Cinderblock shops line the narrow streets near the church. Drab, gray houses made of cement cling to the hillsides. Farmers have carved fields into the steep forest. Patches of yellow corn stubble form sharp rectangles against the green.

[CARO SPEAKING SPANISH]

Rosendo Caro is a forester. He's a thin, handsome man, a field worker for the World Wildlife Fund. Caro tells me that this whole region, where the monarchs live, is unfit for farming. But people still plant corn here because they're poor. They have no choice.

These villages used to live in harmony with the butterflies. But now the human population is growing fast. Families have more children. They clear forest to open new fields. A study published this month in the journal Conservation Biology shows that 44 percent of the monarch sanctuary is already damaged.

[SOUND OF CAR AND BIRDS CHIRPING]

MANN: And then there's the pressure of commercial logging. Three sawmills sit on this short stretch of country road, not far from Angangueo.

[CARO SPEAKING SPANISH]

MANN: They're not much to look at, open shacks made of corrugated tin. But Rosendo Caro tells me there are 50 of these mills working in the area around the monarch sanctuary. That's enough capacity to cut twice the number of trees allowed under Mexican law. The extra trees, Caro says, will be cut illegally. A half dozen men are working inside, behind a barbed wire fence. They won't talk to me. They're polite enough, not threatening or angry. They just don't want any trouble. But researcher Lincoln Brower says tree piracy is out of control.

BROWER: I have been following the illegal logging that's getting into the buffer zone. In the past year, they're cutting over the top of that mountain, down into the very valley that the monarchs use to stage their spring migration.

MANN: Brower says law enforcement efforts have been clumsy. Mexican government officials declined to be interviewed for this story. But park rangers at the sanctuaries are little more than tourist guides. There are no fences around the core zones, not even signs to show the park boundaries. According to the World Wildlife Fund, police are too poorly trained and equipped to stop the tree cutters.

BEZAURY: We're talking about very good, organized illegal bands with machineguns, radios, trucks.

MANN: Juan Bezaury is head of the World Wildlife Fund in Mexico. Sitting in a stately office, in a tree-lined neighborhood of Mexico City, he looks more like a corporate executive than an environmentalist. And in fact, his plan to save the forest has a lot to do with hard cash. In theory, Bezaury says, Mexican law has protected the butterfly sanctuary since 1986. But the laws mean little to local peasants, desperate to make a living.

BEZAURY: No payment was made to the people who owned and lived out of those core zones. So basically, destruction of the forest continued.

MANN: Now, using a six-million-dollar fund, raised from an American foundation and from the Mexican government, Bezaury has begun writing checks. He's paying money directly to the peasant land collectives that own the forest. According to Bezaury, these organizations, called ejidos, receive payment based on how well they protect the monarch habitat.

BEZAURY: We need to protect those forests for the use by the butterfly. But we're going to compensate you not using the forest, so the forest stays. So a whole new paradigm comes into play here. That's the big concept of the project.

MANN: The program is one of a half dozen initiatives designed to reshape the local economy. Bezaury is buying up commercial logging contracts, hoping to shut down some of the sawmills. There's a push for more tourism, and for eco-friendly tree farms down in the valleys. The idea is that villagers near the sanctuary will come to value the butterflies, maybe even help protect the forest.

[SOUND OF CAR DRIVING]

MANN: I want to know what villagers think of these efforts. So I drive back to the highlands. This time, I'm headed for El Rosario, the largest part of the monarch sanctuary that's open to the public. El Rosario is supposed to be a major tourist attraction, a model for the new prosperity. But I find myself on a narrow mountain road. The track is washed out in places, and actually passes through a mountain stream.

[SOUND OF DRIVING THROUGH STREAM]

MANN: There are signs of timber cutting everywhere. Whole swaths of forest have been cleared. On the edge of the grove where the butterflies gather, a village has grown up. Clapboard houses and rickety tourist shops line the cobbled road.

[DOG BARKING AND VILLAGE SOUNDS]

MANN: I'm met at the sanctuary entrance by an elderly man wearing a tidy suit and cowboy boots. Leaning on his cane, he introduces himself as Remedios Teyes Cruz. He's one of the leaders of El Rosario's ejido. This land collective has refused to join the Wildlife Fund's program because the payments are too small. And, Cruz says, because locals aren't sure who to trust.

[CRUZ SPEAKING SPANISH]

MANN: Shaking his head, Cruz tells me that the Mexican government is making a lot of promises. The government claims that villages affected by the monarch butterflies are receiving millions of pesos in compensation. So we want them to show us, Cruz says, where did those pesos go? Who got the millions of pesos?

This kind of suspicion is common. The villages that surround the sanctuary have endured years of neglect and government corruption. And it's true, that the World Wildlife Fund pays only about half the timber's market value. A fundraising effort is underway to beef up the payments.

In the meantime, people here say they are doing their best to protect the forest. While browsing in one of the shops, I meet a young man named Ramiro. He asked me not to use his full name. Ramiro supports his family by leading tours into the sanctuary.

[RAMIRO SPEAKING SPANISH]

MANN: There is illegal logging in other ejidos nearby, he says. But here, we don't have that problem. Here, we take care of the forest. Because we make our living from the butterflies.

Ramiro sounds sincere. But among the tourist knickknacks, next to hand-stitched butterfly napkins, I find dozens of little toy logging trucks. It's a sign that people here are still ambivalent, unsure about the promises of a new economy. The hope, of course, is that villagers will build a new relationship with the monarchs. But there's so much need here, so much poverty.

[SOUND OF HIKING AND THE FOREST]

(Photo: Lincoln P. Brower, Sweet Briar College)

MANN: As I climb back into the forest, the valley feels less remote, less like a sacred place, and more like a piece of disputed real estate. For a while, I just stare, watching and listening. The trees are draped in orange and black bunting. And then, suddenly, the butterflies erupt.

[SOUND OF BUTTERFLIES FLYING]

MANN: The idea that all this could vanish is beyond comprehension. Imagine losing a phenomenon as essential as the Grand Canyon or the fall foliage in New England.

It's not that monarchs would be extinct. They'd still exist in Florida, and on the West Coast. But if this forest isn't saved, the monarch migration that graces the eastern U.S. could disappear. Lincoln Brower from Sweet Briar College says the danger is very real. This winter, a few weeks after my visit, the forest was slammed by an ice storm. According to Brower, the broken tree canopy left the monarchs vulnerable.

BROWER: The damage was horrendous. We were seeing literally millions of dead butterflies on the ground, places where they were in piles up to your knees. The forest acts as a blanket and an umbrella that protects the butterflies from freezing after these storms go through. Cutting out a single tree can result in literally killing tens of thousands of butterflies.

MANN: Now that spring has come, Brower says he's confident the population will recover. There might be fewer monarchs in our gardens this summer but the living migration will survive another year. The fear is that despite the new initiatives, logging will continue unchecked. If so, this winter's monarch die-off could be a sign of things to come. For Living on Earth, I'm Brian Mann in El Rosario, Mexico.

[MUSIC: Cocteau Twins, “A Thinner Air,” VICTORIALAND (4ad – 1986)]

CURWOOD: And for this week, that's Living on Earth. Next week,

[SOUND OF SHIP HORN]

CURWOOD: International shipping is fouling the air around the nation's ports.

MAN: You can't ignore the pollution coming out of the smokestack of the big ships. All you have to do is look at them, sometimes, in the harbor, and it's just thick, black exhaust pouring out of these things sometimes. And it's amazing that people don't stop and notice.

CURWOOD: But the nation's top regulators say there's not much they can do about ships that are registered in Panama and Liberia.

[SOUND OF SHIP HORN]

CURWOOD: Ship pollution, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC OUT]

[SOUND OF WATER, BIRDS, AND INSECTS]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with some flying creatures from the mangrove forests of Venezuela. Fishing bats skim the surface of Lake Maracaibo, as they trawl for small fish for their dinner. Chris Watson recorded these sounds at water's edge.

[Chris Watson, “A Passing View (Fishing Bats),” STEPPING INTO DARKNESS (EarthEar – 2002)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Jennifer Chu, Jessica Penney, Cynthia Graber, Maggie Villiger and Al Avery, along with Peter Shaw, Leah Brown, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson and Milisa Muniz. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Rachel Girshick and Jessie Fenn. Alison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our Technical Director is Dennis Foley. Ingrid Lobet heads our Western Bureau. Diane Toomey is our Science Editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our Senior Editor. Chris Ballman is the Senior Producer of Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood, Executive Producer. Thanks for listening.

WOMAN: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth's expanded internet service. The William and Flora Hewlett foundation for reporting on Western issues. And the Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. environmental and development issues.

MAN: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth