Supercharged Hurricane Season

Air Date: Week of April 12, 2024

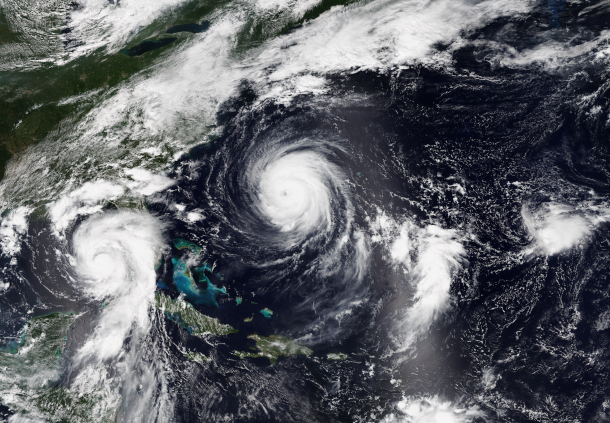

Three simultaneous tropical cyclones form in the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season. Idalia (left), Franklin (center), and what would eventually become Jose (far right). (Photo: S imagery from NOAA's NOAA-20 Satellite, NOAA View Global Data Explorer, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Some scientists are predicting this year’s Atlantic hurricane season will be extremely active as a La Niña develops amid ocean warmth linked to global warming. Meteorologist Ryan Truchelut of Weather Tiger joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the science behind these factors and how people along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts can stay safe.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

If you live or work near the Atlantic or Gulf coasts, listen up: Some scientists are predicting this year’s hurricane season will be extremely active. They include Ryan Truchelut, the chief meteorologist at Weather Tiger in Tallahassee, Florida, and he’s on the line now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Ryan!

TRUCHELUT: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So, in June, the formal start of the Atlantic hurricane season begins. Look into your crystal ball, what are the indicators that you see that can give us a good prediction for this coming summer when it comes to those hurricanes?

TRUCHELUT: Well, when you're making a forecast for the hurricane season overall activity in March or April, there's really two main predictors that you look at at this time range. And those are, is the Pacific going to be in an El Niño or a La Niña? And how warm is the tropical Atlantic Ocean? And right now, unfortunately, both of those factors are likely to be very favorable for highly elevated Atlantic hurricane activity in the 2024 season.

CURWOOD: Hmm. Sea surface temperatures are hotter. How much hotter?

TRUCHELUT: Well, they've really been breaking records here as we've gone through winter 2023-24. They were very, very hot during the 2023 hurricane season, and they never really cooled off. So the average temperature in the tropical Atlantic, kind of the region that we watch for hurricane development as the season rolls forward, has been about a third to half a degree warmer than it ever has been previously in a northern hemisphere winter.

CURWOOD: It's changing now from the El Niño to the La Niña, as you say. What does that do to hurricanes?

Hurricane season 2024 outlooks are calling for a hyperactive season. However, it's still too soon to confidently predict U.S. impacts.

— WeatherTiger - weathertiger.substack.com (@wx_tiger) April 4, 2024

Our analytics show a >90% chance of a top tercile ACE season, but only a ~55% chance of top tercile season from a U.S. landfall perspective. pic.twitter.com/CQqp1n8u2i

TRUCHELUT: Well, unfortunately, that is also very favorable for hurricane development in the Caribbean Sea, the western Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico. And the way that that matters, people often ask me, you know, why does it matter what's happening in the Pacific, we're looking at the Atlantic. Well, El Niño and La Niña really set the tone for weather patterns worldwide. When the waters of the Central Pacific near the equator are warmer than average and we're in an El Niño, that results in a weather pattern that results in unfavorably strong upper level winds over the western Caribbean and the western Atlantic that are unfavorable for hurricane development. So when there is an active El Niño, the Atlantic hurricane season tends to be quieter than normal. In La Niña, when the waters of the Central Pacific near the equator are cooler than average, it's just the opposite. Those upper level winds are lighter than average over the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. That's favorable for tropical storms to develop and intensify. And unfortunately, that means it's often a busier than average hurricane season in the Atlantic when a La Niña is going on.

CURWOOD: Now, last year, we had the El Niño and still there was some pretty tough hurricanes that hit the Gulf of Mexico, Florida. So, it sounds to me with La Niña switching on, it's like adding steroids to the system.

TRUCHELUT: Right. Last year, the 2023 hurricane season was a real conundrum for hurricane forecasters, because we'd never faced such a divergence in those two key predictors. Atlantic sea surface temperatures were very, very warm. Record warmth, far above average. But at the same time, we were looking at the development of a pretty strong El Niño in the Pacific. So there was a real question in the hurricane research community and hurricane forecaster community of which of those influences was going to win out. And in the end, it was a busier than average hurricane season, it was about a third more active than average. Fortunately, most of that activity stayed out to sea in the central Atlantic. But as you point out, I'm in North Florida. So we had to deal with a threat from Category Four hurricane Idalia in late August. It's very unusual for the Gulf Coast to be threatened by a Category Four hurricane during a strong El Niño year. But it's that offsetting Atlantic warmth that really gave some of the storms an extra boost last year.

CURWOOD: And now we're going to move into a situation where those accelerators, those additive factors are coming together. Warmer ocean and a La Niña. Ryan, if you wouldn't mind, just crack open your history book for us for a moment. Talk to me about some of the past years that have had similar conditions to the ones that you're seeing for this upcoming 2024 season. How did those years fare?

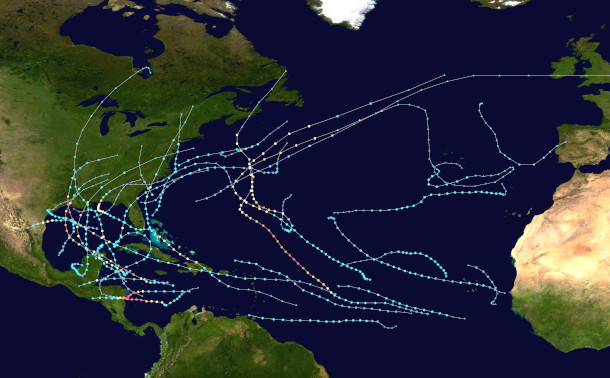

A map tracking all the tropical cyclones in the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season. With similar conditions of very warm tropical Atlantic Ocean temperatures and a peak season La Niña, 2020 is a good indicator of how much hurricane activity the Atlantic is likely to see in 2024. (Photo: MarioProtIV, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

TRUCHELUT: Well, in the past few decades, we do have a couple other years that we can use as reference points. The key ones are 1998, 2010, and 2020. In all three of those seasons you started out the year with an ongoing El Niño. That El Niño weakened and dissipated by the summer months and was replaced by a La Niña in the fall. The Atlantic sea surface temperatures were also warmer than average in those key development regions in each of those three years. Now not quite as warm as we are right now in 2024. But certainly warmer than average. All three of those years were significantly more active than a normal Atlantic hurricane season. More active by about 75%. So, all three of them had essentially the same amount of overall activity. But if there's something that's a little bit comforting to take away from this, it's that those three years had very different outcomes in terms of impacts on the continental United States, as well as populated areas bordering the Caribbean and in Central America and Mexico. In the 1998 hurricane season, the United States saw three hurricane landfalls, but no major hurricane landfalls. We did see Hurricane Mitch, which was a horrible storm for Central America, one of the worst of all time in the Caribbean. In the 2010 hurricane season we saw next to no impacts in the continental United States. We did see some hurricane landfalls in the Caribbean and in Central America, but it was a light year for the United States even though there were a lot of hurricanes out in the open waters. Unfortunately, in 2020, that was a very, very busy hurricane season. Not only did we have the most named storms ever on record, with 30, but we saw seven major hurricanes, and numerous landfalls along the Gulf of Mexico coast, including Category Four Hurricane Laura. And we also saw horrific storms in Central America going into October and November of that year. We had Eta and Iota off the Greek name list that just pummeled Central America deep into November. So there's a range of outcomes still on the table. Just because it's an active hurricane season doesn't necessarily mean that it'll be a very busy one for the United States. But it certainly does raise the baseline risks when there's more activity.

CURWOOD: Looks like conditions are right for a hyperactive season this year. What will meteorologists, folks like you, be watching out for as we get closer to June?

Putting those together, that means 2024 is going to be in rare company, among just 8 other years since 1950 to have a cool Pacific and very warm Atlantic.

— WeatherTiger - weathertiger.substack.com (@wx_tiger) March 22, 2024

Six of these eight years were "hyperactive" Atlantic hurricane seasons, with 60-150% more activity than normal. pic.twitter.com/kYrMTWjMG1

TRUCHELUT: Well, we'll be watching to see if there's any changes in the depth or the extent of that warmth over the tropical Atlantic. Those sea surface temperatures can change with time. They can warm up, they can cool down. They can pivot pretty quickly as trade winds shift. So I will say it's going to be difficult to pull back the warmth. We're so far above average that even if they cooled off, we have a lot of cushion and we'd still probably be well above average for the season, heading into the peak of the season, even if we don't warm up quite on the rate that we have been. And we'll also watch to see how La Niña is developing in the Pacific. Right now, there's every indication that El Niño will be ending over the next month or so. And we'll be proceeding pretty quickly through neutral conditions and then into La Niña by the end of the summer. But if that changes, if there's a delay or we don't see La Niña developing quite as quickly as many of the models now suggest, that, too, would change the risk profile somewhat. So, you know, overall, kind of the way that I phrased this in my seasonal outlook is that we're very likely to have an above average hurricane season. That's almost baked in at this point. But we don't know are we going to have a size L hurricane season or are we going to have a size XXXL? How many extra larges are we going to have in terms of impacts? That's still up in the air.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about what those who are in the hurricane parts of the world should know in preparing for a season with this elevated risk.

TRUCHELUT: Well, people who live along the coast need to have a plan for what they would do if a major hurricane is heading in their direction. And when, once the watches and warnings go up, once you receive evacuation orders from local emergency management, you need to know what you would do in that circumstance, where you would go. Now in many cases, when you receive an evacuation order, you don't need to flee to another state. You just need to move far enough inland so that you're above the dangerous floodwaters and surge waters that are occurring along the immediate coastline. So know your surge zone, know your evacuation zone and be ready with a plan to heed that order when the time comes. Because that will save your life. You can hide from wind, but you need to run from water.

CURWOOD: The media often focuses on the speed of the hurricane. OMG, it's a Category Four, it's a Category Five, but I gather from your work the storm surge is a much bigger risk to people. Talk to me about that, please.

Ryan Truchelut is co-founder, president, and chief meteorologist at WeatherTiger. (Photo: Courtesy of Ryan Truchelut)

TRUCHELUT: That's true. For a long time we focused on wind. Wind is how we categorize and classify hurricanes. The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is completely based on the maximum sustained wind. Now, maximum sustained wind only occurs in a tiny sliver of a hurricane’s eyewall. And it really, that maximum wind is only occurring offshore. Anytime a hurricane moves over land, just the friction between the wind and the trees and the buildings slow down those maximum sustained winds. So that's really not the right focus to have as we're kind of holistically evaluating the total threat that a hurricane poses to life and property. Now, wind is a serious risk. I don't want to play that down. It certainly does quite a bit of damage when a major hurricane makes landfall, but only about 10% of the deaths and casualties in a hurricane are caused by wind itself. The vast majority of damage and casualties are caused by flooding and storm surge flooding, river flooding, excessive precipitation, as well as the wind pushing those waters on shore. So as hurricane forecasters and risk communicators, science communicators, we're kind of trying to move away from the category of a storm and kind of think about all the different threats that a hurricane poses, whether it be wind, surge, flooding or tornado threats.

CURWOOD: Okay. Ryan Truchelut is chief meteorologist at WeatherTiger in Tallahassee, Florida. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Ryan.

TRUCHELUT: Of course. Thank you. Anytime.

Links

WeatherTiger | “Atlantic Hurricane Season First Look: March 2024”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth