Orbital: An Earth-Centric Novel Set in Space

Air Date: Week of March 22, 2024

Orbital by Samantha Harvey is a fictional novel about twenty-four hours in the lives of six astronauts aboard a space station orbiting earth. (Photo: Courtesy of Grove Hardcover)

The handful of astronauts and cosmonauts on board the International Space Station float in a strange paradox, with the Earth constantly in view, but always out of reach. The 2023 novel called Orbital explores the splendor of planet Earth as seen from orbit through a day in the life of six astronauts up on the ISS, and author Samantha Harvey joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss her book.

Transcript

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

At any given moment there are a handful of humans orbiting the Earth aboard the International Space Station. These astronauts and cosmonauts live in a strange paradox. For them the Earth is constantly in view, but always out of reach. They carry photographs of loved ones to keep them close, but these astronauts are still orbiting 250 miles up. Tethered emotionally and by the pull of gravity to the only home our species has ever known, they become each other’s family for six to twelve months. A new novel called Orbital imagines a day in the life of six astronauts up there as they circle the Earth every 90 minutes. Author Samantha Harvey joins us now to discuss. Welcome to Living on Earth!

HARVEY: Thank you, Jenni. It's my pleasure to be here.

DOERING: So Samantha, could you start us off by reading a passage from the beginning of your novel Orbital?

HARVEY: Okay. "Rotating about the earth in their spacecraft they are so together, and so alone, that even their thoughts, their internal mythologies at times, convene. Sometimes they dream the same dreams — of fractals and blue spheres and familiar faces engulfed in dark, and of the bright, energetic black of space that slams their senses. Raw space is a panther, feral and primal; they dream it stalking through their quarters. They hang in their sleeping bags. A hand-span away beyond a skin of metal the universe unfolds in simple eternities. Their sleep begins to thin and some distant earthly morning dawns and their laptops flash the first silent messages of a new day... Some alien civilization might look on and ask: what are they doing here? Why do they go nowhere but round and round? The earth is the answer to every question. The earth is the face of an exalted lover; they watch it sleep and wake and become lost in its habits. The earth is a mother waiting for her children to return, full of stories and rapture and longing. Their bones a little less dense, their limbs a little thinner. Eyes filled with sights that are difficult to tell."

Orbital features descriptions of fictional astronauts performing experiments, reconstituting dehydrated meals, and living an astronaut’s daily routine on a space station. (Photo: NASA, NASA.gov, public domain)

DOERING: In that passage you just read from the introduction, you have this line, "The earth is the answer to every question. The earth is a mother." And one thing I just loved about this book is how central of a role Earth plays in it despite the fact that this is set in space. Most space novels are about escaping Earth's gravitational pull entirely. What made you decide to write a book like this?

HARVEY: Well, I think you sort of hit the nail on the head in that for me, this was always about the Earth more than it is about space. I think it's really interesting and mind blowing to look out at the cosmos and to see it from that vantage point of low Earth orbit. So it wasn't that I didn't find that interesting. But the thing that I wanted to focus on was the view of the Earth, because it's so singular from that vantage point because 250 miles up isn't actually very far, you know. You don't get an entire view of the Earth, you just see the sort of a limb, the Earth's limb, kind of rounding away beneath you. And you can see... not detail. You can't see traces of humanity. And I think that's very interesting. But you can see the natural world. You can see the continents. You can see forests. You can see desert. Obviously ocean, you can see the different types of ocean, that the oceans in different climates across the world, the different colors, the different blues and greens. And I think that distance is both intimate and panoramic and distant. I think is a very sort of kind of paradoxical vantage point to write from. And that's what interested me about it, that it's so intimate, such an intimate view of our planet. You're not far from it, It's kind of tenderly, the space station is tenderly circling this planet. And yet, of course, it's detached from it. It's outside of its atmosphere. It has a different view to any view we could have on Earth. And I think that that contradiction, that sort of bashing together of different perspectives is really interesting to me.

DOERING: Now, Orbital is built around the 16 sunrises and sunsets that these astronauts see in a 24 hour period as they orbit the Earth 16 times per day. And it seemed to me that this structure mimics some of the themes in the book. How did you decide on this really short, narrow timeframe?

HARVEY: Yeah, it didn't come to me at first, actually, that in the first draft, the book was written over a month. And I wrote it from the point of view of just one of the astronauts, and I found that I couldn't say what I wanted to say. I knew that it was a novel I wanted to write, but I couldn't find the means to say the things I wanted, to get to the heart of what I wanted to say. And I was getting bogged down in the repetition of breakfast times and lunchtimes and dinner times over a month. I knew that I wanted to talk about time, the way time has exploded in space. And it occurred to me, after a conversation with a friend actually about the book that I needed to be cleverer about it. I needed to use the structure of the book to say some of things I wanted to say about the dislocation, that disorientation of being in that environment and the fact that you're going around the Earth every 90 minutes. And then it just became perfectly obvious to me that it should be one day, 16 sunset, 16 sunrises that we, as the reader should experience and the book should try in some way to simulate the experience of going around the earth and how one day really just can't feel like one day in many ways. So as soon as I decided on that structure, the whole thing fell into place and everything aligned, and I rewrote it very quickly. And the book shrunk as a result, and it's compressed down to the length it is now which is quite short. So it suddenly began to work. I could make it do the things I wanted to do. I could focus on the imagery, on the sense of time on the dislocating experience of being there without having to contend with endless kind of domestic concerns about their daily schedule over a month.

DOERING: You have this line in your book, "Space shreds time to pieces." I love that.

Astronauts eat food far more typical than the space ice cream found in many museum gift shops. (Photo: NASA, NASA.gov, public domain)

HARVEY: I mean, obviously, I don't know what it's like to be in space. But if you even watch videos of the Earth, of the ISS orbit online, on the NASA website, or YouTube or whatever, you feel this kind of steady progression of the craft around the planet and the rapidity of the sunrise coming upon you. It's dark, and then suddenly, this light rushes across the face of the earth, in a sort of biblical way, that takes your breath away, even watching it on a video, and suddenly it's daylight, and you're in a different continent. And what do you do with that, as someone who's in orbit, experiencing that and when your space agencies are tethering you to a 24 hour clock. And they're trying to structure your days quite rigidly around a 24 hour clock, but nothing that you're experiencing out of the window is reinforcing that. So again, the weird dissonance between the time that is imposed on you from the ground and the time that you're experiencing space creates a sort of weird limbo that you have to somehow function in. So I wanted to imagine what that might be like. And, of course, it is only my imagination.

DOERING: Right? I mean, you know, I've never been up to space. You've never been up there. And yet, you're able to really delve into what it might be like, as an astronaut on the International Space Station. You talk about everyday life and even how they clean the toilets. So how did you go about researching such a unique experience?

Orbital takes place on a fictional version of the International Space Station. In the book, there are six astronauts and cosmonauts from America, Russia, Italy, Britain, and Japan. (Photo: NASA/Roscosmos, NASA.gov, public domain)

HARVEY: Well, actually, it isn't hard to research this subject, because there's so much information about it. I don't know if you've ever spent very long or any time on the NASA website, but is a deep labyrinth of a place. You can spend a lifetime there. And it has so much information about all aspects of what NASA is doing, but particularly the ISS. I read books by astronauts. I watched endless material films and videos made by astronauts. I did countless online tours of the space station. And everything is there to be found out. And then you get the more kind of niche material. I downloaded the ISS Maintenance Manual [LAUGH] and understood, probably 4% of what I was reading. That's probably generous, probably less than that. But I could get a sense of how many moving parts there are and how much maintenance it requires. And then once I was started, I continued to research the subject throughout the writing of the book. So that became a weaving together of research and imagination and allowing the two to sort of exist in a dance together and to constantly feed one another.

DOERING: And as the astronauts up there orbiting the Earth 16 times a day, they watch this typhoon that's traveling across the Pacific Ocean and building in the Pacific Ocean, and then gathering strength. This is the only disaster that happens in the book. It's on earth, not in outer space. Why was this important to include?

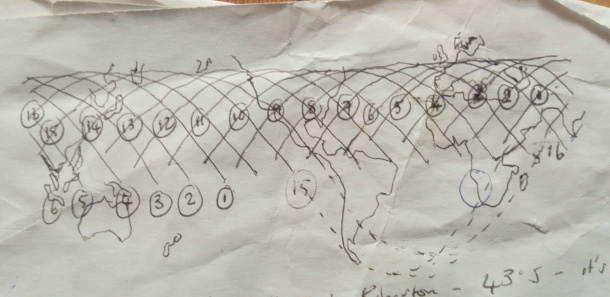

The map of the ISS’s orbit that Samantha Harvey made and referenced while writing Orbital. It was eventually turned into the map included in the front of the book. (Photo: Samantha Harvey)

HARVEY: I wanted something that would kind of mark out time in the book in a straightforward way. So from the beginning, I thought that would probably be a large weather event of some kind so something that is inexorably moving across the earth. And in this case, it's a typhoon that is moving toward the Philippines. Also, I wanted to get to the beauty of some of these weather events from space. And again, the contradiction of that because we know the destruction, they cause on earth but from space they're quite beautiful and mesmerizing. And you can really see the way the weather shifts about the surface of the earth and how the rotation of the earth is pulling the winds and spirals. And I wanted to be able to write about that because it's just actually very inspiring to watch. And also, we know that there are increased weather events, that weather is getting more extreme because of climate change. So I wanted to be able to speak to that without having to make any great claims or lectures on the state of the planet and of climate change. But to be able to say, look, here's something that is happening more frequently. It is something that astronauts see from space quite regularly. It is beautiful; it is magnificent; it is destructive and terrible. And I wanted to be able to hold both of those views in place at the same time, that worldly view and the view from space.

DOERING: It is a really interesting way to be able to observe and sort of comment on what's happening with the earth right now with the climate crisis. Because it is this thing that's so big and huge, that it's usually hard for us to like, even conceive of what's happening. But you're able to narrow this down to a 24 hour period, and to the six astronauts and their perspective. And like watching them, watch this typhoon in the Pacific.

HARVEY: It's hard to know how to think about climate change. It's one thing to sort of intellectually understand what's happening. But to get a grasp on that emotionally or visually, is quite difficult. And I think this was one way of me doing that. And I didn't want this book to be a climate change novel. My motivation was quite different. My motivation was actually to write about beauty and to write about rapture and joy and the splendor of this planet that we live on, you know. I wanted to convey something of what I feel when I look at images of the Earth from space. So I think part of what is implied by looking at the Earth from space and what is implied by its beauty is also the way that beauty is being compromised. And climate change is held within that distanced view of the Earth. It is there to see. And there's a passage in the book in which I sort of talk about that a little bit about how actually, it seems at first, when you look down, it's this kind of humaneness, innocent, unblemished sphere, actually, when you know what to look for, you start to see the signs of mankind, even though you can't see mankind itself, you see signs of it, and of what we are doing to the planet. And that is just a fact of that viewpoint. So it seemed a way of holding the whole view there in front of me at once and just writing about it with a sort of an honesty and sincerity with an eye on its beauty. And to let the rest be implied and to let the reader make of that what they will. And it's just trying to hold a view of the Earth, to the reader to myself, and say, "This is what we have. This is the magnificent thing we have. What do we make of it?"

Samantha Harvey is the author of Orbital and five other books. (Photo: Matt Lincoln)

DOERING: I certainly felt like the Earth is this mother as you write, but it's also really fragile. And it's also this pale blue dot that we can see in this tiny dot in that picture that Voyager took as it turned back towards Earth. At the end of writing this book, how fragile did you feel the earth is? Or did you come away with more of a sense of just how massive and grand it is?

HARVEY: It's interesting when I was writing the book, and I was trying to come up with the descriptions for the earth, you know, obviously things like fragility come up a lot. And it seems like it's made of ether, or it seems like it's made of glass. And it seems rather tiny, because you can orbit it 16 times a day. It's actually not very big. You're in Asia, and suddenly, you're in Australasia, and then suddenly you're in North America, and it hasn't been very long. And the more you watch the videos of these orbits, the more you just become very used to the view. It's like, oh, yeah, there's the East Coast of America. Oh, yeah, there's Central Europe. There's Southern Africa. And it all becomes very familiar, almost like a park, you walk in every day. You come to think of the Earth as quite a small thing. But then at the same time, it's huge. You can't see any manmade objects by day, you know. They just vanish in the immensity of the natural landscapes. And I think in the end, what I came to understand was, the Earth is small, but it's not vulnerable. It's not fragile. It's a lump of rock in space. It will outlive us. We are the vulnerable things — the living things on this planet, the plants, the animals,. It's us we need to think about. I think there's a bit too much talk when we think about climate change of protecting the earth. And I think that's a very abstract way of looking at it. You know, actually, we're trying to protect ourselves and the other creatures that we are fortunate enough to share a planet with. That's what's at stake. We must protect the beings, the... all the living things on this earth, that's our priority. The earth is going to prevail, anyhow.

DOERING: Samantha Harvey is the author of Orbital and five other books. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

HARVEY: Thank you. It was my pleasure.

Links

Purchase Orbital and support both Living on Earth and local bookstores.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth