The Human Toll of Pollinator Loss

Air Date: Week of March 10, 2023

With declining numbers of insects like bees, the yield of pollinator-dependent crops decreases significantly. (Photo: Andreas Trepte, avi-fauna.info, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5)

A study conducted by Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health shows the decline of pollinators is contributing to the deaths of an estimated half a million people a year worldwide. That’s because yields of nutritious foods like most fruits, vegetables, and nuts are falling as the pollinators they depend on disappear. Dr. Sam Myers, the study’s lead researcher, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how this falling yield is linked to more preventable deaths from ailments such as heart disease and diabetes.

Transcript

BASCOMB: A study conducted by Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health shows the decline in pollinator populations linked to fruit, vegetable and nut production is leading to the deaths of an estimated half a million people a year worldwide. Pollinators such as butterflies, bats and bees are in dramatic decline so farmers are producing smaller amounts of pollinator-dependent crops. Fresh produce and nuts help keep us healthy and decrease the risk of diseases ranging from heart attacks and stroke to type two diabetes. The loss of pollinators is making healthy foods more costly and less available resulting in more deaths from preventable diseases. The lead researcher of the study is Sam Myers, an expert on planetary health at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

MYERS: We found almost half a million people a year are dying. And the relationship is that we need pollinating animals to optimize the yields of what we call pollinator dependent crops. And, in particular, there are a whole groups of foods in our diet, including fruits and vegetables, and nuts, that are really important in protecting us from diseases like heart disease and stroke, and some cancers and diabetes. And when we don't eat as many servings of those foods, we die in higher numbers as a result of those kinds of diseases. And so what we wanted to understand is, how is the lost production of those kinds of foods actually leading to higher mortality and people around the world from those types of diseases?

BASCOMB: And what exactly did you find?

MYERS: It was a little bit complicated because what we needed to do was actually string together the research from four different groups. And so we started with an understanding from our colleagues in pollinator ecology, who had built a whole network of experimental farms around the world on four different continents, over 300 farms, and had actually measured how much of the reduced production, what's called the yield gap, the gap between the best performing farms and the farms they were working on, how much of that gap was because there weren't enough wild pollinators to optimize the crop yields. And they have found consistently, that about a quarter of the yield gap across the world is from not having enough wild pollinators present. We took those numbers and worked with a second group that actually calculated the yield gaps for all pollinator-dependent crops all around the world on five square kilometer grids, so the entire world and all of the food that we produce. And so we calculated the yield gaps of all pollinator-dependent crops, then we asked if those foods had been produced, how would they have entered the global food trade system and how it would have changed the prices. And using what's called a bio econometric model, which is called IMPACT, we actually calculated how those foods would have moved through the food trade system, and who would have purchased and consumed them. And then finally, working with a fourth group, we could calculate if those foods had been consumed by those populations, how would that have changed their risk of mortality from diseases like heart disease, stroke, some cancers, and diabetes? And what would the total additional mortality have been? And that's where we got this number of just under half a million deaths per year.

Above is a graph indicating the number of deaths caused by pollinator deficits by income level. Unlike with many environmental issues, those with the lowest income are the least affected while those in the middle-income bracket suffer the most. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Sam Myers)

BASCOMB: So is this problem of, you know, lack of pollinators and health uniform across the world? Or are you seeing regions where it's specifically concerning?

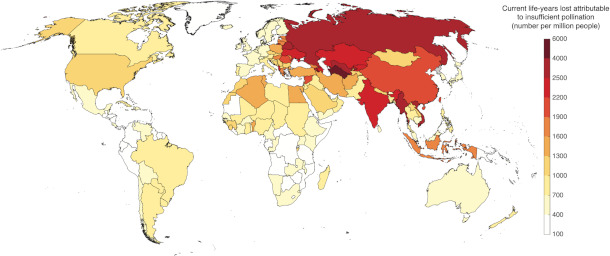

MYERS: You know, the percentage of the yield gap that's being seen on experimental farms on four different continents tends to be pretty robust and uniform that across the board, there's about a 25% of that yield gap is because they're not enough pollinators, how that actually affects the health of different populations and the income for different populations varies enormously by region. And so the greatest vulnerability to the last production of these food groups tends to be in places that already have high prevalence of these diseases like heart disease and stroke, which is primarily the more developed countries with more sedentary lifestyles that are already transitioning to these metabolic diseases, and that are not so wealthy that they can overcome increased prices for these foods by just, you know, paying more money. And so we saw a lot of vulnerability in parts of Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Republic, parts of China. And of course, within every national population, including the United States, there are certainly people who fit that category of having high risk of these diseases but not enough income to be able to overcome higher prices of these food groups.

BASCOMB: You know, usually when we talk about these types of issues, it's the most low income communities that are often disproportionately affected by environmental problems. But it seems like that's not quite the case here.

This map of years of life lost that can be attributed to pollinator deficits displays that it is middle income countries that are the most affected. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Sam Myers)

MYERS: No, and this was similar to a finding we had in a paper we wrote in The Lancet in 2015, where we saw a very similar sort of at-risk population that was sort of middle income because the diseases that are affected by not consuming pollinator dependent crops are diseases like heart disease and stroke, which actually are less prevalent in the lowest income countries and more prevalent in these middle income countries. And so, yes, you're right, this sort of defies the usual pattern of the greatest vulnerability being among the very poorest populations in the world, and instead, we're finding vulnerable populations in wealthier countries.

BASCOMB: Well, generally, how are farmers responding to the reduced yield in their crops from this loss of pollinators? And I understand that that may be different in different places. But generally speaking, what are you seeing there?

MYERS: Well, the opportunity to respond is what's really exciting. You know, and it's probably worth saying that not only is there this big nutritional challenge associated with insufficient pollinators, but there's a big economic challenge associated. And so we actually looked at a few case study countries, Nepal, Honduras, and Nigeria, and showed that between 13 and 30% of the entire agricultural GDP of those countries was being lost due to insufficient pollination. So this is this free service, right? It's the bees and the ants and the butterflies that are living nearby that are providing a free service that increases the yield of these crops. And when they're not present, the farmers see a real loss in their total income. In terms of what they can do, there's actually really strong consensus among the pollinator ecology community that there's a suite of what are called pollinator-friendly practices, things like planting hedgerows around your farm or intercropping, you know, other species between the crops that you're growing in a field or reducing your use of pesticides, particularly neonicotinoid pesticides, which are really hard on insect pollinators, all of which have been shown to have a real positive impact on improving pollinator populations. And they've also been shown to pay for themselves. So even though you have to take a little bit of land for the hedgerows, or for the intercropping, because you increase the yields on the remaining land, it actually pays for itself quite well. So from a policy standpoint, it would make all kinds of sense for countries to actually institute these pollinator-friendly practices as a way of bringing back these populations. Of course, it would also help the biodiversity crisis sort of writ large by providing habitat and forage for other animals that were losing in high numbers.

Without access to foods like fruits, vegetables, and nuts, people are at a much higher risk of getting chronic diseases such as diabetes. (Photo: picryl, public domain)

BASCOMB: It seems though, that farmers would need a lot of support to be able to implement those strategies versus, you know, if you don't have that support, and you're just a farmer, your yield has dropped, maybe you just need to clear more land. I wonder to what degree are farmers, you know, just taking that approach, because that's what they've done in the past when yields are low?

MYERS: Well, it's a great point. And I think they do need support, not so much financial support, because as I said, within two or three years, these practices tend to pay for themselves, they may need a little bit of support as for the initial investment, but more than anything, they need sort of agricultural extension kinds of support to understand what the practices are, and how to actually institute them. You know, when we look sort of toward the future, and we think about the fact that we're going to add maybe another 2 billion people to the planet's population, we need to produce a lot more food at the same time that pollinating insects and other pollinating animals are actually in decline. So the two trends are sort of going in the opposite direction. It is really concerning in terms of that trend. And if we think about well, so how do we maintain adequate supply of things like fruits and vegetables and nuts, if we don't have pollinators, then our only opportunity is going to be what we call agricultural extensification meaning we have to clear more land, which has more impact on biodiversity, use more agrochemicals, more water, more fossil fuel. And so the ecological impact of replacing pollinators with these other approaches is actually quite enormous. And that's what's so interesting to me is there's this sort of nexus of health effects, economic effects, and environmental effects, all of which point to the real importance of instituting these pollinator friendly practices on farms around the world.

BASCOMB: Sam Myers is a principal research scientist at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Meyers, thank you so much for your time today.

MYERS: It was great to be with you. Thank you.

Links

Learn more about the decline of insect populations around the world

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth