Eat Like a Fish

Air Date: Week of December 6, 2019

Picture of Bren Smith cleaning oysters. Oysters sequester carbon from the ocean to manufacture their shells. (Photo: GreenWave)

Overfishing and climate change are hitting fish stocks hard, and at the same time most of the food grown and raised on land is carbon-intensive and unsustainable. The answer, says former industrial fisherman Bren Smith, is restorative ocean farming. In his book Eat Like a Fish, Bren Smith chronicles some of his adventures at sea and what he’s learned about sustainable food production as he has transitioned to ocean farming. To learn more, Living on Earth’s Lizz Malloy caught up with Bren Smith on his boat off the Thimble Islands of Branford Connecticut.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

As we heard before the break, life on the high seas can be unforgiving and even deadly. But plenty of rough and tumble fishermen choose a life on the ocean. A love of the sea and the adventure it can provide has been drawing in fishermen for generations. One of them is Bren Smith. Bren Smith left high school in Newfoundland when he was just 14 and took up work on fishing boats in the open ocean. In his new book, Eat Like a Fish, Bren chronicles some of his adventures at sea and his new job, farming. And to be clear he’s now an ocean farmer and founder of Green Wave, an organization dedicated to sustainable and restorative ocean farming. To learn more, Living on Earth’s Lizz Malloy caught up with Bren Smith on his fishing boat in the Thimble Islands off Branford Connecticut.

MALLOY: Alright, so can you tell us a little bit about your restorative ocean farm? What are you doing here?

SMITH: I used to be a commercial fisherman, and over the years have been on this journey to try to figure out: what does it make sense to grow in the ocean? Like ask the ocean? What should we grow? Like, how should we farm it? And if you ask the ocean that it says something pretty simple, it says: Why don't you grow things that you don't have to feed and don't swim away. And so we're out here, trying to reimagine aquaculture and grow a mix of shellfish and seaweeds and grow as many things that, as we can in a 20 acre area, but not any species, species that restore rather than deplete ecosystems. So something like our kelp soaks up five times more carbon than land based plants, it's called the Sequoia of the sea. Our shellfish filter nitrogen out of the water column, where our farms are really creating these really dynamic ecosystems that mimic Mother Nature.

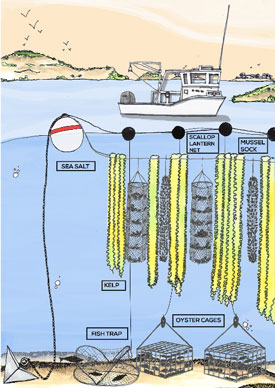

3D Ocean farming works by taking advantage of space and incorporating seaweed, scallops, oysters and clams. (Photo: GreenWave)

MALLOY: That's awesome. And why do you call it 3D ocean farming?

SMITH: So we call it 3D ocean farming because it uses the entire water column. When you're farming underwater if you just create a simple rope scaffolding system of buoys, anchors, and ropes, it's really cheap, right, doesn't cost much money to start one of these farms, but it's a really efficient use of space. So we can grow our kelp from the surface vertically downward, right next to mussels in mussel socks, scallops in lantern nets, these are all vertical and then we have oyster cages down below and clams in the mud and just really using every bit of water we can and that's good because it has a small footprint. You know, very much like vertical farming in urban areas.

MALLOY: Why do you feel like you are in this position where you are now with restorative ocean farming?

SMITH: So I grew up in Newfoundland, Canada, little fishing village called Maddox Cove right next to a fisherman's Co-Op, you know, kids were selling cod tongues door to door, dropped out of high school when I was 14 and headed out to sea, fished in Gloucester, Lynn Massachusetts -- tuna, lobster -- then headed to the Bering Sea, where I fished cod and crab. And I was working at the height of industrialized fishing, you know, tearing up entire ecosystems with our trawls, we were chasing fewer and fewer fish further and further out to sea. And most of the fish I was catching was going to McDonald's for the fish sandwich, which is a sandwich I still love and sneak away to eat regularly. But don't tell the foodies that. And I love that job, so even though we were destroying ecosystems, you know, just the humility of being in 40 foot seas, that sense of solidarity of being in the belly of a boat, working with other folks, and that sense of meaning of helping feed my country. But then the cod stocks crashed back in Newfoundland and that was a real wake up call for a whole generation of us. And it's what taught me that not protecting ecosystems is not an environmental issue. It's not about birds and bees and bears. It's about jobs. It's about kitchen table issues like, there will be no jobs on a dead ocean. And that's when I kind of joined the environmental movement in a certain way. And, you know, the, our journey now into climate change is the same thing. There'll be no jobs on a dead planet, there'll be no food on a dead planet. So, I remade myself as an early ocean farmer, growing salmon. And that was supposed to be the answer to overfishing, right, and job creation, we're going to feed the planet. Instead, it was just, you know, essentially pig farms out at sea polluting local waterways, growing really neither fish nor food. And what aquaculture did that point was trying to grow around existing markets. So grow what people want to eat. So people want to eat salmon, they want to eat tuna, that's what they grow. And I got disillusioned and then kept searching and I ended up here in Long Island Sound and remade myself as an oysterman. But it was just the beginning of early boutique, sort of specialty oyster companies emerging, and I was right outside New York. So I built a business around that. And then Hurricane Irene and Hurricane Sandy came in and destroyed my farm two years in a row. And so suddenly, I found myself like on the front edge, a canary in the coal mine of the climate crisis that arrived essentially 100 years earlier than we were expecting. So that was a, you know, a depressing time for two years in a row and seeing this as a new normal, but it forced me to adapt, you know, and I think some of the best creativity, and this gives me hope in the era of climate change, comes when humans are in crisis, right. And that's really where we are. So I just took from the oyster that question of, you know, what should we be growing in the ocean and learned that there were thousands of edible plants, hundreds of kind of shellfish we could grow. And that was the beginning of my journey.

Brendan Smith is founder of GreenWave and author of Eat Like a Fish. (Photo: GreenWave)

MALLOY: So in your book, you include some recipes, which are pretty great. They looked really tasty, and I'm kind of excited, I want to try some. Where did you find these recipes? Did you come up with them, like, where'd they come from?

SMITH: Yes. So, uh, we worked with a lot of chefs over the years and what's been interesting is I started by working with seafood chefs. And it turns out seafood chefs were not the right folks to figure out what to do with sea vegetables. They kept on like baking seaweed salads or wrapping them around fish. And then I discovered this other sector, which people that specialize in making vegetables unhealthy. And I think Brooks Headley out of New York, who's a former pastry chef and a punk rock drummer, and that now run Superiority Burger and he's figured out how to make vegetables absolutely delicious and not worry about the health, so I gave him the kelp and he immediately made kelp noodles, barbecue kelp noodles with parsnips and breadcrumbs. It's just brilliant, right? The heat of the barbecue sauce, that softness of the parsnips, the crunch of the breadcrumbs, and it just completely de-sushifies seaweeds and you know people eat it and they just, they don't even think seaweed. So, and another chef we work with who has recipes is Dave Santos, who's an incredible Portuguese chef in New York. And just luckily, we're at this incredible moment of, sort of, American culinary experimentation. But it's hard to change tastes right? It's slow, and we don't really have time to bank everything on just changing tastes. So our other strategy is to make the seaweeds the soy of the sea but not evil, right, soy is extremely problematic. We all know the story about deforestation, things like that. We don't have that trouble with seaweed. But the soy industry did something fascinating in the 50s. They sat down and said, Okay, we're never going to get Americans to eat soy. So we'll put it in everything. And look at any label, whether it's like furniture to food, you're going to find soy in there. It's just woven through all the industries, so, we can take our seaweeds and do the same thing because seaweed’s an incredible fertilizer that's been used for a 100 years, can be used as animal feed: If you feed cows a 2% diet of asparagopsis, you'll get a 58% reduction in methane output. And this delicious tasting meat and milk and, stunning, we can use it for bioplastics. So the London Marathon just had seaweed water bottles.

MALLOY: Wow.

SMITH: So imagine that we've got this plastic crisis in the ocean. It's killing our oceans as farmers we could actually grow crops that we can turn into packaging like, this gives me hope. And if we do this right and we grow these crops, we can just weave it through so many different industries and create jobs don't have to wait just for changing taste.

MALLOY: Yeah. So your farm serves as a new ecosystem for so many different species that are living in these waters, as well as a community space. Can you talk about that?

SMITH: I mean, it's designed to be a community space, we don't own those waters. What we own is the right to grow shellfish and seaweeds. Anybody can come boat, swim, fish on the farm. And it turns out that if you start farming all these species together and do a polyculture system, you're recreating, you're just mimicking Mother Nature, which then attracts all these different species, whether it's, you know, ducks or seals or striped bass or crabs. It becomes this living ecosystem. As a farmer, you then just become a steward of this area. And so we can mix both revival of the ecosystem creating the shoreline parks that people can enjoy, while also saving and protecting these community spaces. I mean, think of these as underwater community gardens.

Brendan Smith (left), Living on Earth's Elizabeth Malloy (center), Jill Pegnataro (right) farm manager and hatchery technician. (Photo: Paloma Beltran)

MALLOY: That's amazing. So how did you really start becoming an advocate against climate change? And, are you seeing this becoming more of a common thing in the fishing community?

SMITH: So, I became active in the climate movement, not out of choice, it was because my job was directly impacted. You know, my farm was wiped out by Hurricane Irene and Hurricane Sandy. Climate change was supposed to be this slow lobster boil that happened over 100 years instead, it's here and now. So I don't have a choice, right? I didn't come to this as an environmentalist. I came to this with the perspective that there are going to be no jobs, no food on a dead, like, that I have a stake in this. And I think the new climate movement isn't just about environmentalists, it's people from all walks of life that are being impacted by this, this crisis and all of us coming together to figure out solutions. One of the first things we did was we took our boat down to the Climate March in New York, took a group of shell fishermen, fishermen down there, and I was amazed that you know, we enjoyed the people doing urban gardening in Detroit, we joined the coal miners who were trying to solarize the haulers, you know, and I just felt the first time like, this is my community.

MALLOY: It's really interesting that you say that, that felt like a real community for you. I mean, I think climate change has done so many things. But one of the things it's really done is brought so many people from different walks of life together to figure out different ways to survive and move forward to thrive.

SMITH: I think of it as the politics of Yes, right. Where we're all coming together around solutions like environmentalists traditionally have been the politics of No, you stop pipelines, you know, you stop hog farms, and that's the politics of No, it needs to be done. Right. But we now need a politics of Yes, of what are we going to build? What are we going to do? It's not about waiting for other people to do this and for us to decide, you know, is it good or bad? It's like, let's build a future we want. What's exciting on the ocean is that it's kind of a blank slate. Like we can actually do food right, do agriculture the right way. Take all the lessons of industrial agriculture, all the lessons of industrial aquaculture, and not make the same mistakes, right? We can weave justice into the DNA of this new economy. Make sure, you know, young beginning farmers, indigenous folks, women all have access to this new economy, we can make sure our seed isn't privatized. Make sure people do polyculture not monoculture. I mean, I think that's the exciting thing. Like we can actually build a new economy from the ground up and do it in the right way. And that's, you know, there's a lot of potential there.

MALLOY: Yeah. It's incredible. So, you saw some pretty crazy things as a commercial fisherman, and this is somewhat of a calmer lifestyle now so how are you adjusting to that.

SMITH: Yeah. I mean, it was rough, right. I mean, you know, I can't go to the same bars I used to and I now get beat up. What am I going to be like? Yeah, I was out today. And I pulled up this amazing piece of kelp. Like, I gotta hang out with arugula farmers and drink tea or something, right. This was not the path for me, right. I'm a hunter, I'm a, you know, I have that sort of last generation of folks that hunt the earth for food, but I've had to say goodbye to it, and I really had to rewire my nervous system, but over time I've, I've really learned to love it. It is amazing feeling to lift a wall of plants out of the ocean, right and this sort of the shimmering, sort of deep brown colors, it really has, has changed me. I do miss being a fisherman. I miss that sort of adventure of the high seas, the thrill of chasing fish around the globe, but I still get to die on my boat one day. Like, that's the measure, like, I'm out here on the Mookie, and I'll be able to say goodbye to the world. As I sink into the ocean. I think that that'll be enough for me.

Links

The GreenWave Official Website

Ideas.Ted | “Vertical ocean farms that can feed us and help our seas”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth