Surfing the Web to Heat Your Home

Air Date: Week of February 13, 2015

Project Exergy's prototype is called Henry (Photo: Project Exergy)

To survive the snowy cold of winter, most people in the Northern United States heat their homes with oil, gas, or wood. Project Exergy wants to change all that, and founder Lawrence Orsini tells host Steve Curwood that we could soon be heating our homes with our personal computers.

Transcript

CURWOOD: In rough winters like this one, where at times it’s been below freezing in every one of the 50 United States including Hawaii, few have avoided the cost and hassles of heating. And now there is a technology on the horizon that could make the burning of gas, oil and wood to heat homes obsolete, thanks to computers. A new company called Project Exergy is developing a way to capture the waste heat from computing to keep our houses warm. Lawrence Orsini is the founder of Project Exergy and he says his innovation is based on the fact most of the energy used by our personal computers is turned into heat.

ORSINI: Computers are really efficient little resistance heaters. The amount that gets used in computation is so small it probably can't be measured. So the majority of it, all of it really, is converted directly to heat. So every watt that goes in comes out of the computer as a watt of heat.

CURWOOD: And so right now we spend a lot of energy trying to cool down computers whether at home or the big ones at the office. How hard is it do you think to capture all that heat and put it to work instead of throwing it away?

ORSINI: Well, so the interesting thing that maybe differentiates our project a little bit from others that are looking at this is we’re not just really looking at just capturing heat. We want to generate significantly more heat. We're actually running these things a little bit different than most people do. Instead of running them cool and capturing the heat that normally generate, we look to run them really hot, so we're taking a different twist on this.

Project Exergy's prototype is called Henry (Photo: Project Exergy)

CURWOOD: So why do you want to have the computer run hot, hot, hot, especially if it doesn't like being run hot, hot, hot?

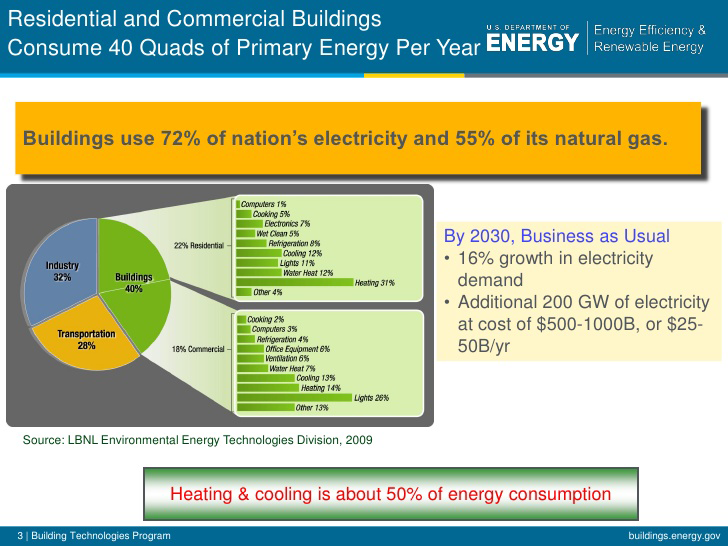

ORSINI: Well, I've been in the energy industry for about 15 years, and I've had the opportunity to look out across the US and see where energy gets consumed. So there's some good data that the US Energy Information Administration has on consumption of natural resources and energy in buildings. So about 40 percent of all the energy that’s consumed in the US happens in commercial and residential buildings themselves, and close to half of that energy is used for heat, so it was interesting to me comparing that or actually contrasting that against the two to three percent of electricity that's being used today in data centers. And thinking about the way that data centers work, you know, and thinking about the way industry thinks about computers, they really try hard to keep those computers cold. A significant amount of energy actually goes into refrigerating the heat out of data centers and putting it out into the atmosphere. In fact, some of the most efficient data centers are actually moving closer and closer to the Arctic Circle to cooler climates so they can just take the roof off and let the heat go directly to the atmosphere. To me, that seems a little bit backwards. If our economy and buildings and industry actually run on heat, then we ought to be focused on making that heat and not getting rid of it in our data centers. So the idea of running computers hotter comes from that notion, the notion that if we need a significant amount of heat, let's figure out a different way to run computers and create that heat with computers.

CURWOOD: So go online and look at Facebook and help recycle that heat, huh?

Henry's temperature gauge (Photo: Project Exergy)

ORSINI: That's it. Yeah. I mean there's there's a lot of reasons for us to really consider this. Science Daily pointed out, I guess overall, that 90 percent of all the data in the world has been generated over the last two years, and I don't think anyone's predicting, you know, that it's going to slow down at all, it's actually accelerating. Think about how that's going to impact the energy consumed in data centers...it's headed for the roof. I personally don't think we're going to be able to sustain that without doing something like this. So disturbing the computation and putting the heat where we need the heat is a much better way to do it. It's pretty hard to ship heat, it's pretty easy to ship data.

CURWOOD: Now, Lawrence, today's computers are made with the concern that they could overheat so manufactures try to minimize the heat that the processor is exposed to, but you want reverse that. You want computers to crank out as much heat as possible and you have a prototype named Henry?

ORSINI: We do, Steve, yeah. We spent the last two years working on Henry, figuring out how to make it actually run significantly hotter, so Henry's a liquid cooled high-performance computer that makes significantly more heat than a typical computer does, in fact, we've been able to boil water across some of the heat exchangers that are on the cooling...that are on the graphics cards and actually storing the thermal storage tank almost 200 degree Fahrenheit water. So that's pretty hot. I personally don't know of any other personal computers that are running that hot, and we can put this in every house in the US. In fact if we did that and we distributed that 2 to 3 percent of energy that is being used in data centers, some of our rough calculations say that we can probably heat near 80 million houses.

CURWOOD: By the way, how big is the computer that's the source of the heat that you use for your home?

Project Exergy's prototype is called Henry (Photo: Project Exergy)

ORSINI: Well, the computer itself is the size of a - well it’s a little bit bigger than the normal tower PC. In fact, we specifically chose to make it out off-the-shelf parts so you know there is no Star Trek technology in this thing. It's made out of things that you could go buy from the computer store today.

CURWOOD: And how much of your home does it keep warm?

ORSINI: Well, we live here in Manhattan so the building carries a little bit of its own warmth, but you know over the winter, the last two years, last year and this year, we haven't turned heaters on once.

CURWOOD: So, by the way, how possible would it be to share energy among homes so that a home that is creating a lot more heat than it needs could give as well as sell that heat to someone else. Heat is somewhat hard to move around, I gather?

ORSINI: It is a little bit hard to move around. One of the components we're designing to work with this is a thermal storage tank. This thermal storage tank is filled with phase change material that holds significantly more heat than say your water heater would, so you can run it hard and sock away a lot of that heat. So we've had some brainstorming sessions for some of the team and said, "You know we could probably make it so that these thermal storage tanks are removable so that if you have a need for computing and you didn't have a need for heat you can share the heat with your neighbors by taking the storage tanks next-door and dropping it in their house and running it in their house.

Heating and cooling is about 50% of overall energy consumption. (Photo: DOE)

CURWOOD: So how long before I could begin capturing some of the heat from my computer?

ORSINI: Well that depends on how quickly we can get this thing together. So the next stage of development, we've just launched a Kickstarter campaign so we can fund the next couple of prototypes and then pursue some research funds with the Department of Energy as well. If we can manage to land those things then we'll probably have a few prototypes in the field by the end of the year, and if those do well then I would say in two years we would be ready for a production run of units that you might be able to put into your house.

CURWOOD: Lawrence, I don't want to discourage you but there's a lot of money made in making computers these days by some pretty big companies and all their stuff will become obsolete if what you're talking about will come into play. How can you change this whole industry to take advantage of this energy?

ORSINI: Well, quite a few people have said that this is an intentionally very disruptive technology and I don't choose to think of it that way. I think a lot of companies out there like Amazon, Google, Microsoft, those folks have been innovators, and an idea like this would encourage them to jump into innovation once again. There's a need in our country I think for sort of a new vision, a new industrial revolution. So I would love to see companies like that jump on the bandwagon and start innovating alongside us. This is something that's going to happen. If you look at how energy consumption is climbing through the roof on computation, we have to do something about that. I don't think it’s sustainable personally.

CURWOOD: I'm wondering if you have a dream configuration, which consists of a bunch of solar panels outside collecting all this electricity to drive these computers that are heating homes on a neighborhood, house by house, neighborhood by neighborhood basis, so that we would never need gas oil coal like that again.

Lawrence Orsini (Photo: Project Exergy)

ORSINI: You have looked into my future. [LAUGHS] Yeah, being in the energy industry and watching what's happening to distributor generation and the way that solar photovoltaics are proliferating, Henry would be a perfect device to connect with a PV system because when you think about it the PV system produces electricity when the sun comes up, and if you have a load that actually produced the majority of the benefit you need for your house, which is heat, that also started working when that electricity started producing, then you've got a pretty interesting combination of technologies, and because the heat is stored in the thermal storage tank, you can use it whenever you want to. You don't have to use it just when the computer’s running, so Henry actually makes some of the largest loads in your house adaptive to great condition making the local grid around you far more resilient and hopefully bringing everybody's utility costs down.

CURWOOD: Lawrence Orsini is the founder of Project Exergy. Thanks so much for taking the time today, Lawrence.

ORSINI: Absolutely, thank you so much for having me.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth