John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire

Air Date: Week of June 6, 2014

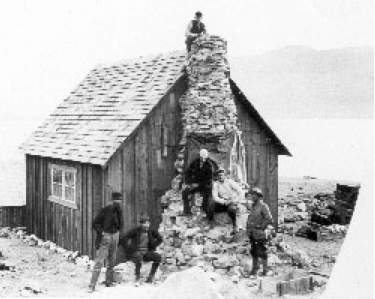

John Muir and geologists at his Glacier Bay cabin (National Park Service)

Author Kim Heacox argues that John muir might never have become an environmentalist had he not visited Alaska, and discusses his new biography "John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire" with host Steve Curwood.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Well, Alaska is a state of rare wild beauty that's increasingly also on the front lines of arguments about energy development and climate change. But the state also has a rare place in the history of American environmentalism, through no less a figure than John Muir. For most Americans, Muir is associated with Yosemite, the California state quarter bears his likeness along with an image of Half Dome. But John Muir might never have become an environmentalist without a visit he paid to Alaska. Author Kim Heacox posits in his new biography, "John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire," that the wildest adventure Muir ever embarked upon was his canoe journey to what is now known as Alaska's Glacier Bay. We talked to Heacox on a rather scratchy Skype line at his remote Alaskan village.

HEACOX: Glacier Bay was instrumental in John Muir’s coming to Alaska. 250 years ago the bay was all glacier and no bay, and he heard about this bay, and he wanted to come up to Glacier Bay to verify his theories of glaciation, and he proposed this theory that the Sierra Nevada and especially Yosemite Valley had been carved by glaciers, and this was heresy at the time because the lead geologist at the state of California, Josiah Whitney, said the valley had been created by catastrophic downfaulting. And Muir had no scientific credentials, he was working in a lumber mill. In John Muir’s life the single greatest adventure he embarked upon was this 40-day canoe journey in October, November of 1879 with 14 Indians and a Presbyterian missionary to find the tidewater glaciers of Glacier Bay.

Muir Glacier (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Now, what was John Muir finding to be so capitivating about these glaciers in Alaska do you think?

HEACOX: Well, they’re massive, and they are still at work. You can see readily that the land is shaping them, and they’re shaping the land. Down in California, you have to use your imagination, try to imagine that a glacier once tried to build an entire valley, that glaciers once flooded this entire mountain range. When you go to Alaska, you see a landscape dominated by ice, where here and there mountain peaks stick through.

CURWOOD: What was it about Muir’s character that set him up for this kind of expedition and curiousity about glaciers do you think?

HEACOX: That’s a great question. I wrote in my book that Muir would be to glaciers what Jacques Cousteau would be to the oceans and Carl Sagan would be to the stars. If I have to pinpoint the turning point in John Muir’s life, it’s when he walked away from home, it’s when he walked away from his domineering father and the cultivated manicured world of Wisconsin and walked into the wild. He embarked on a 1,000-mile walk from northern Kentucky to the Gulf of Mexico. He worked his way down to the Isthmus of Panama, took a boat up to San Francisco, saw Yosemite for the first time - all profound experiences. If you’re going to walk away from your family, from your culture, from your community, from your nation, everything starts over again.

Glacier Bay (Photo: National Park Service)

CURWOOD: How important were Muir’s Alaskan trips for inspiring action towards establishing a national park and conserving wildlands?

HEACOX: John Muir redefines Alaska for America. The US had purchased Alaska in 1867. Secretary of State William Seward, and of course the media called it “Seward’s ice box”, “Seward’s folly”...it’s a sucked orange, the Russians have already killed all the sea otters, there’s no more good pelts, there’s no more money. And 12 years later John Muir arrives, sees what he sees as shimmering glaciers of Alaska. It’s magnificent, it’s beautiful, it’s not a wasteland, uselessness, a sucked orange. He goes back. He writes for the Overland Monthly Magazine and some newspapers. And he basically gives birth to the tourism industry in just a few short years.

Paddle wheelers and steam boats are heading up to Alaska from Puget Sound. Muir’s writings inspired Enos Mills who became the father of Rocky Mountain National Park. He was read by Robert Marshall, Aldo Leopold, Olaus Murie, the founders of the Wilderness Society, and on and on and on. Teddy Roosevelt, of course, Muir’s good friend, worked to create the Antiquities Act that passed in 1906 that enables Roosevelt by Executive Order with a stroke of a pen to create national monuments. And of course, they’re supposed to be these 25 and 50 and 100 acres sites to preserve antiquities. Well, Roosevelt ran with it, and he created these massive national monuments, Grand Canyon and Mount Olympus, that later became Olympic National Park and Grand Canyon National Park.

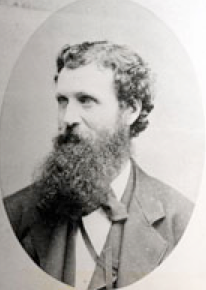

John Muir (Photo: National Park Service)

CURWOOD: By the way, this Antiquities Act was used initally to protect Glacier Bay, you write.

HEACOX: Yes, the Antiquities Act was passed in 1906, but Calvin Coolidge used in 1925 to create Glacier Bay National Monument, and the scientist who spearheaded the attempt to create the National Monument, William Cooper, he read John Muir when he was a little boy, wanted to be a mountaineer and a glaciologist like John Muir, so yes, you take the Antiquities Act from 1906 and many presidents have used it to create national monuments, and many of those national monuments have since become national parks.

CURWOOD: How was John Muir anonmalous for his time?

HEACOX: He was very anonmalous for his time. Today, we have people who are climbing Everest and Denali, and mountaineering and going on long extended wilderness trips. It’s a great thing to do. It’s regarded as healthy. Back in John Muir’s time, he was considered a kook. Nobody else was really doing what he was doing. For example, in 1890 on his third trip to Alaska, he was ill in California. And his wife knew he needed to return to the mountains to get well. He actually called it “mountain nourishment”. So he went to Alaska, out on the ice, he slept on the ice, he fell in a cravass, he soaked himself in cold water. After the fourth day, his cough was gone because he was so happy and in time people began to understand that this guy might really be onto something, that maybe we should set aside these wild places that are actually beneficial to us for our good health and wellbeing.

CURWOOD: If John Muir went to Muir Glacier today, what do you think he would see? How would he respond?

HEACOX: Oh, I think if John Muir went to Muir Glacier today, I think he’d be stunned. He knew glaciers were retreating, he knew the world was warming in his time, the late 1800s, early 1900s, Muir Glacier today is 32 miles further back from where it was in 1890 when John Muir built a small cabin in front of the glacier.

CURWOOD: Now, Muir engaged with President Roosevelt, as you point out in your book, President Theodore Roosevelt going camping with him at Yosemite. But how comfortable was he with Roosevelt’s brand of politics? Because Roosevelt brings in a Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot’s view was that the trees, well, that’s lumber, this is to be used.

HEACOX: John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt got along great. They greatly enjoyed each other’s company. They camped alone, they talked for hours into the night, the two guides that were with them listened in, they commented later that each man wanted to do most of the talking, they were both so exhuberant to tell the other one the way things are and the way things ought to be. And Muir, I guess you could label him, he was something of an idealist, a preservationist, he was not a utilitarian...and then Gifford Pinchot, the greatest good for the greatest number. John Muir would shake his head when he heard that little saying, and he’d go, “Yes. Right. All too often the greatest number is number one.” If you just keep adding more and more people and more and more technology and industry pretty soon you’re going to run out of these so called inexhaustible resources. It was called ‘the myth of superabundance’, and John Muir called it “gobble gobble economics”. He said nothing dollarable is safe. We have to come to a point where we have to just draw a line and say, “No, this place is sacred. It has value beyond utility.”

CURWOOD: You titled your book, "John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire." What’s the fire?

HEACOX: The fire is the fire of conservation, fighting the hard fight. I think the glaciers of Alaska so inspired John Muir. Once you come to Alaska, the wildest place in his life he would ever visit, and you return to - let’s say, California, which is very hustling and bustling and people everywhere, much of it becoming settled very quickly and the forest being cut down. Once you have that looking glass of Alaska, everything else seems small and vulnerable. So he came back down from Alaska, and he said, something has got to change.

CURWOOD: Kim Heacox is author of "John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire: How a Visionary in the Glaciers of Alaska changed America." Thanks so much, Kim, for taking the time with me today.

HEACOX: Thank you, Steve.

Links

More about Author Kim Heacox and his biography John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire

Learn more about the Alaskan rivers and glaciers Muir explored

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth