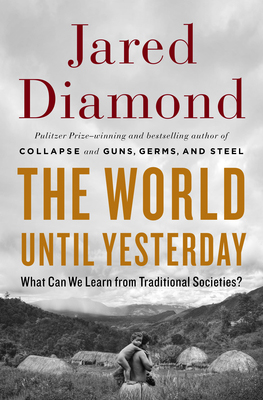

The World Until Yesterday

Air Date: Week of January 4, 2013

|

Best-selling author Jared Diamond‘s new book “The World Until Yesterday” is part anthropology, part personal memoir drawing on decades of field work in New Guinea. He tells host Steve Curwood the book explores lessons westerners could learn from tribal cultures on issues as varied as conflict, childcare and personal safety.

Transcript

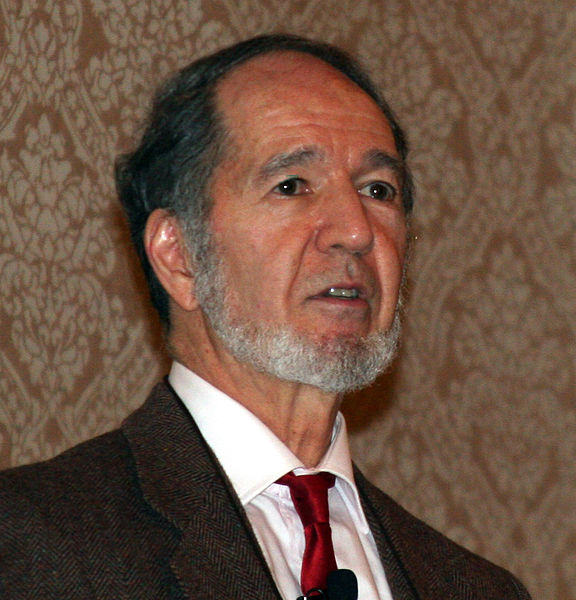

CURWOOD: "Guns, Germs, and Steel" and "Collapse" are two of the mostinfluential social anthropology books ever written. Now author and UCLA professor Jared Diamond is out with a new volume, “The World Until Yesterday.” Professor Diamond intended to write a small book of personal memoirs but says his editors had other plans.

DIAMOND: So, the book evolved into an examination of traditional small societies all around the world throughout history, laced with my anecdotes from New Guinea and learning what lessons these societies have to teach us about how to conduct our own personal lives.

CURWOOD: This new book opens at an airport in Port Moresby, the capital city of Papua New Guinea, where Diamond was struck by the rapid modernization of the island's peoples over the decades that he's done field work there.

Jared Diamond is a UCLA geography professor and Pulitzer Prize winning author of “Guns Germs, and Steel.“ (Wikimedia Commons)

DIAMOND: It's taken a couple hundred thousand years for anatomically modern humans in many parts of Eurasia to transform themselves from hunter-gatherers without writing to famers and industrial people with writing. But in New Guinea, this has happened in parts of New Guinea within a few decades. And some friends of mine in New Guinea grew up making stone tools and then by the time I met them they were using steel tools and they had writing. The changes have been telescoped in New Guinea into a short time.

CURWOOD: One of your most interesting observations was the different number of people who were in the modern airport and how they would have behaved in the past – can you describe some of that for us?

DIAMOND: Sure. The New Guinea capital city airport that I was in, in 2006, was a normal airport in that when I came in there, there was nobody else in that airport whom I knew – everybody was strangers, the baggage attendants, all the other passengers, and for me, of course, that’s no big deal in our modern society, we’re always encountering strangers. On my drive down here today, everybody that I was passing was a stranger.

But in traditional New Guinea and in any traditional society, people don’t move. If you move, there are rules about who is your friend and who are your enemies. Any stranger is assumed to be an enemy. And so that 2006 New Guinea scene where I was surrounded by strangers would have been unthinkable in traditional New Guinea. I would have freaked out, I would have expected to be killed instantaneously, I would have run or started attacking other people.

CURWOOD: Now, you tell an interesting story, in Papua New Guinea, about this tension among strangers, and how folks diffuse the war that would otherwise begin. And what I’m thinking of is the story of this driver for a company who’s zipping along, a kid darts out from behind a bus and gets run over and killed. The driver, of course, is now expecting that the family of this little boy will now try to kill him. How did this situation get resolved and how does that reflect traditional values and how might we use those values today?

DIAMOND: It’s a gut-wrenching story that was told to me by a friend of mine who was in New Guinea. There was a traffic accident, so, a kid ran out incautiously across the street and got killed. If such a thing happens in the United States, the state intervenes, there may be a criminal case if the driver was incautious, and certainly, there may be a civil case where the relatives of the dead child are going to sue the driver for having killed the child.

In New Guinea, it’s different. In this case, the next day, the father of the dead boy came to visit the employer of the driver. And the employer was afraid that there was going to be violence but, no, the father of the dead boy wanted to settle the matter in the traditional New Guinea way by payment of compensation. In this case the compensation was large by New Guinea standards, it was several hundred dollars and some food, but trivial by our standards.

And after negotiations, on I think, the fifth day after the accident, the relatives of the dead boy, the father and mother and uncles, sat down together for a meal with the employer of the driver. They made speeches in which they talked about missing the dead boy. My friend made a speech in which he ended up crying because he said, ‘I’m identifying with what you must be going through because I also have young children and nothing can compensate for the death of a young child.’ The end result after five days was that the whole matter was settled, there was emotional clearance, the people went on with their lives, whereas in the United States, the idea that after 5 days you would sit down with the killer of your child is unthinkable. Instead, there would be a lawsuit.

So, this illustrates that in New Guinea, disputes are settled in a way that aims at emotional clearance and getting on with your life. Whereas in a state government, you never meet the person again, the last thing you hear about is emotional clearance and you spend the rest of your life churned up with feelings left over from the accident.

CURWOOD: Now, traditional society in many respects sounds wonderful, and then there are horrible things like killing babies, you mention in your book that sometimes if a baby is born and has a deformity, or sometimes in the case of twins, the mother will kill the newborn for the sake of the tribe as a whole. Can you explain that?

DIAMOND: Yes, it’s true that in many traditional societies, babies who are born impaired are killed. What on earth, though, can you do if you are living in a marginal society? It’s also the case that if you are living in traditional societies, some of them are abandoned or killed…their old people. But what again can you do if you are a small group that is walking to the next camp and you’ve got an old person who is not capable of walking? So, there are both things that we find horrible in traditional societies, and things that we find wonderful in them – often how they bring up their children, often how they treat their old people, how they approach danger, how they remain healthy.

CURWOOD: When you write about the elderly, you title your chapter “Treatment of Old People: Cherish, Abandon, or Kill” and I suppose that sums it all up, but perhaps you could expand on that for us.

DIAMOND: Those are the extremes of choices about what to do with old people. This is an issue that interests me increasingly having passed my 75th birthday some months ago. I used to, when I was a child, thought of 75 as being really old. And now it feels to me as if I’m entering the prime of life. So, in traditional societies, depending on circumstances, old people may be abandoned if there is no way for taking care of them, for example, if the society is nomadic; old people may be encouraged to commit suicide, they may be actively killed.

But at the opposite side, old people in societies that are sedentary, that live in permanent huts and villages where it’s easy to take care of old people, then old people will spend their old years surrounded by their children and relatives and friends and they have much more socially rich life, satisfying life, they have much more value than in modern American society.

CURWOOD: I thought the section on raising children was really fascinating. Here in the US most of the games our kids play are teaching them, well, how to compete with their peers. But in your experience from New Guinea, the games that children play in are largely about teaching them how to share. Why do you suppose that is?

DIAMOND: Probably because they are living in small societies where the people with whom you are playing games are the people you’ll be dealing with for the rest of your life. It’s the case that in a really small society, one individual is not supposed to get ahead, instead any individual who is successful is expected to share what he or she gets with other people. But conversely, if you are down on your luck, then you can get food and things from other people.

So, sharing is necessary for survival in traditional societies, in contrast with modern American society. We stress the individual, getting ahead, you do as well as you can and you’re certainly not going to share everything you’ve acquired with all of your relatives and cousins and people you knew 10 years ago.

CURWOOD: As we were preparing for our interview with you, this was happening just as the mass shooting came to light in Newton, Connecticut. I kept wondering how would a tribal community handle a member of the tribe who was emotionally unbalanced in that way.

DIAMOND: I’ll give you an example of how a tribal community did deal with a member of the tribe who was emotionally unbalanced. This example came from the Kung San people of the Kalahari Desert of Southwest Africa. The Kung formerly, occasionally, killed each other, and when state control came into place over the Kung, the killing stopped. But there was among the last killings, there, a Kung man who was really, really dangerous and possibly deranged by our standards. He had killed several people.

And finally what happened was that a group of men went into his band, he was there surrounded by members of his band, and in the presence of his relatives, they killed him. The relatives did not interfere because they recognized that this guy was dangerous and deranged, they were too afraid to take care of him themselves, but they did not interfere when other people eliminated him. So, that’s one way to deal with dangerous people in small-scale societies.

CURWOOD: You coined a term in this book that you call constructive paranoia. And you write a couple of chapters about dangers and how to stay safe with this concept - tell me more about this.

DIAMOND: Sure. Dealing with danger is one of the things that I observed in New Guinea and that I have learned that have had the biggest impact on my life and my attitude towards nature. I was camping out with some New Guineans, I was picking campsites in a forest, and I picked what I thought was a gorgeous campsite under a colossal, beautiful tree. And, the New Guineans with me freaked out and they said, ‘we’re not going to sleep under this tree.’ And I said, ‘what’s the matter? Why not?’ And they said, ‘because the tree is dead.’ And I looked up and saw that yes, it is dead, but it was such a big, huge tree that I said ‘it’s not going to fall down for 50 years, don’t be silly.’

But, no, they were not going to sleep under that dead tree. I thought their fears were exaggerated, but then, as I spent more time in New Guinea forest, I realized: OK, well the chance is 1 in 1,000 that this tree is going to crash on me tonight, but if I expect to spend 10,000 nights in the forest because I expect to live 30 years and I spend a lot of time in the forest, if I ignore 1 in 1,000 risks, by the time I’ve run that risk 10,000 times, I’ll have died 10 times over.

How that affects me now is that when I shower in the morning, I recognize that for older people, slipping in the shower is one of the big risks of life, and yes, the chance of my falling down in the shower this morning was only 1 in 1,000, but I intend to take a shower every day for the next 20 or 30 years, and if I’m not careful in the shower then I’m going to end up with a broken hip and then probably be dead. So that’s an example of constructive paranoia guiding my own life. I’m very careful about small things that each time you do them aren’t dangerous but that will eventually catch up with you if you’re not careful.

CURWOOD: Jared Diamond, you are 75 years old now, and you spent most of your adult life traveling back and forth to remote corners of the earth and spending time among traditional tribal peoples. So how did the things you learned inform how you live your life and the way that you raised your own children?

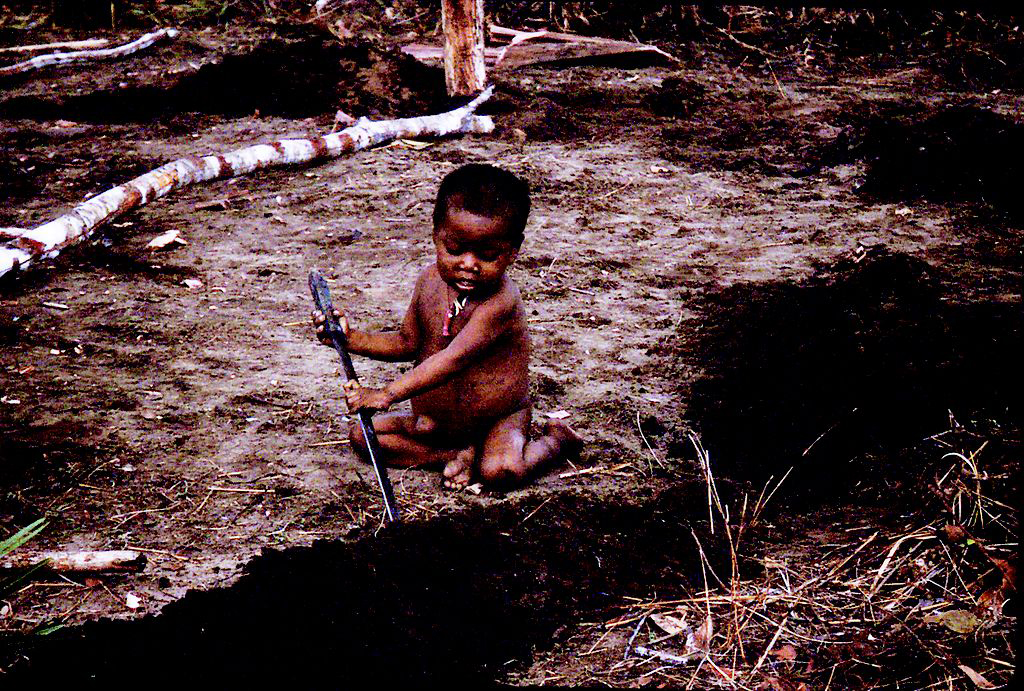

DIAMOND: One is my attitude towards danger that I mentioned. The other is raising children, so I have twin sons who are now 25 years old, and my observations from New Guineans raising their own children informed my raising my children. One thing is that New Guineans and traditional people in general allow their children as much freedom as possible. They consider children to be autonomous creatures capable of making their own decisions and I let my kids make their own decisions insofar as possible.

There were some surprising results (laughs). At the age of three my son Max fell in love at first sight with snakes. My wife and I are not snake lovers, but alright, Max loves snakes and let’s help him keep snakes as pets and Max ended up with 147 pet snakes and frogs and lizards. Eventually he got beyond snakes and he got interested in cooking so now he’s a professional chef. But that’s an example of allowing kids the opportunity to choose what they want.

And still another example is that never, not once, did I ever hit my children. I found that it was possible to get them to do what was necessary, to discipline them, without hitting, and, that’s again something that I’ve learned from New Guinea; you never, never hit a child.

CURWOOD: Jared Diamond, what can we expect next from you? Another book, I suppose?

DIAMOND: Yes! I already have an idea for another book which I expect to publish around my 82nd birthday, but I’m still thinking about what might go into that.

CURWOOD: Seven years to write.

DIAMOND: Yes. They take a long time.

CURWOOD: Thank you so much Jared Diamond.

DIAMOND: (Laughs.) You’re welcome.

CURWOOD: Jared Diamond’s new book is called “The World Until Yesterday: What We Can Learn from Traditional Societies.”

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth