The Sometimes Frost

Air Date: Week of February 25, 2011

Large chunks of soil collapse as a result of permafrost thaw and erosion, as this image taken along the Sagavanirktok River on the North Slope of Alaska near Deadhorse shows. (Photo: Kevin Schaefer)

Scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Snow and Ice Data Center have published a new study with surprising results. They found that the vast frozen tundra in the arctic region could soon defrost and release vast amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Host Bruce Gellerman talks with climate scientist Kevin Schaefer, the lead author on this study.

Transcript

GELLERMAN: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville Mass, this is Living on Earth. I'm Bruce Gellerman. National security and energy security - a conversation with former CIA chief James Woolsey about the threat posed by our dependence on foreign oil. But first - the scales are tipping: global warming is converting vast carbon sinks into huge carbon emitters.

Two regions that store enormous amounts of climate changing gases are undergoing dramatic changes themselves. In recent years, devastating droughts in the Amazon have killed tens of millions of trees in the world's largest rainforest. As they rot, the dead trees will release 13 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. That's as much as China and the United States emit in a year. Now researchers warn even more CO2 could be released in the coming decades as global warming heats up the ground in the frozen arctic.

A thick layer of ground ice is clearly visible in this image of thawing permafrost taken just south of the Brooks Range in Alaska. (Photo: Tingjun Zhang)

Kevin Schaefer is a climate scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado. Dr Schaefer, welcome to Living on Earth!

SCHAEFER: Thank you very much.

GELLERMAN: So, let's talk permafrost. What is it, and why should I care about what happens to it?

SCHAEFER: Permafrost is permanently frozen ground in the high-latitude tundra regions. You imagine on the surface of the ground you've got your vegetation, grasses and mosses. Underneath that you've got a layer of soil that thaws in the summer and freezes again in the winter. And underneath that is the permafrost, permanently frozen ground.

The permafrost starts only about a meter or so from the surface, but it can extend down thousands of feet. We should be concerned about this because the permafrost contains a large amount of frozen organic matter - organic matter that has been frozen since the last ice age, 30-10 thousand years ago.

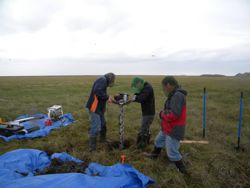

Scientists Tingjun Zhang and Kevin Schaefer explore a typical gully caused by rapid erosion as permafrost thaws on the North Slope of Alaska. Researchers call this landscape ith its irregular hummocks and bogs "thermokarst". (Photo: Lin Liu)

GELLERMAN: So, if I understand your research, what you're saying is that the permafrost is melting, essentially, it's thawing out - and that it's turning from a sink into a source, that is, it stored carbon dioxide and now it's going to be releasing it back into the atmosphere, these greenhouse gasses.

SCHAEFER: The best analogy we like to use is that you have broccoli in your freezer - as long as it stays in the freezer, it will stay stable for very long time, but if you take it out of the freezer, it will eventually thaw out and decay. And that's what we're talking about with the carbon, the organic matter that's currently frozen in the permafrost. This matter has remained frozen for tens of thousands of years. And as temperatures rise, as we put greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere, it starts to thaw out. Eventually the thaw layer will reach the frozen carbon. Once it thaws out it will decay and the carbon will end up back into the atmosphere.

GELLERMAN: So, the earth is getting warmer because of greenhouse gasses - this causes the permafrost to thaw, which releases more greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere, and that causes more warming, and on and on again.

Thawing permafrost leads to rapid erosion, and subsidence, often with small ponds like this, in a photo taken just south of the Brooks Range in Alaska. (Photo: Lin Liu)

SCHAEFER: Exactly. This is called the permafrost-carbon feedback. And, once the carbon is put back into the atmosphere, it will accelerate the warming due to the release of fossil fuel emissions.

GELLERMAN: So are we talking about a runaway climate change here?

SCHAEFER: No, we're not. We're not talking Venus. But we are talking a significant amplification. Now I can't tell you at this time exactly how many degrees additional warming we would see due to this - that's the next phase of our research - but I can tell you that it's a huge amount of carbon. And, we estimate that the arctic will change from a sink of carbon relative to the atmosphere, to a source, in about 20 years.

GELLERMAN: Well, you don't quantify how much carbon dioxide could be emitted?

SCHAEFER: Well, we do. We estimate by 2200, 190 giga-tons plus or minus 64 giga-tons of carbon put into the atmosphere. Now that's a lot of carbon, and to give a perspective, that's roughly equivalent to half of the total fossil fuel emissions since the dawn of the Industrial Age. Or to put it another way, it's equivalent to the emissions from all power plants in the United States for 80 years.

Expansion and contraction as the surface soil freezes and thaws each year form polygons in the permafrost, as seen here in a photo taken near Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. (Photo: Kevin Schaefer)

GELLERMAN: So, right now we're at, what, 390 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and scientists say that's above the safety level. They'd like to see it at 350. So, where would this put us in 90 years?

SCHAEFER: We estimate - maximum possible - about 80 ppm, roughly an additional 20 percent.

GELLERMAN: Instead of 390, we'd be up to'470?

SCHAEFER: Yes.

GELLERMAN: So, what happens to your numbers now?

SCHAEFER: Well, the next phase of the research is to do many more simulations to try to get a better handle on the uncertainty in our estimates. And also to work with other modeling teams to put this into a fully dynamic climate model, so that we could actually quantify how much additional warming or amplification we'd see due to the release of CO2 from permafrost.

Scientists drilling a permafrost core sample on the North Slope of Alaska near Deadhorse. Mosquitoes form a haze around the drilling team. (Photo: Kevin Schaefer)

GELLERMAN: Your figures have not been used in climate models before?

SCHAEFER: No. Ours is the first study to release how much and when carbon dioxide would be released from the permafrost. None of the other models in the inter-governmental panel on climate change include the permafrost-carbon feedback. I do know that many of the modeling teams are working right now to put permafrost-carbon into their models.

GELLERMAN: So what has to be done is we gotta make even greater cuts than are now being voluntarily agreed upon.

Large chunks of soil collapse as a result of permafrost thaw and erosion, as this image taken along the Sagavanirktok River on the North Slope of Alaska near Deadhorse shows. (Photo: Kevin Schaefer)

SCHAEFER: The release of carbon from permafrost is irreversible. Just like fossil fuels. Fossil fuels - once you drill the carbon, drill the oil and burn it, there's no way to put that oil back into the ground. In permafrost, once you thaw out the organic matter and it decays, there's no way to put that organic matter back into the permafrost.

So what it means is that we have to reduce our emissions even more in order to hit a target atmosphere CO2 concentration. The primary results of our paper is that permafrost can release a huge amount of carbon, and that we really have to account for that carbon when developing our global strategies to reduce fossil fuel emissions.

GELLERMAN: Well, Kevin Schaefer, thank you so very much, I really appreciate it.

SCHAEFER: Thank you.

GELLERMAN: Kevin Schaefer is a climate scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, CO. His study appears in the latest online edition of the journal Tellus.

Links

Visit the National Snow and Ice Data Center's website

Read the abstract of Dr. Schaefer's article

Watch U.S. Energy Secretary Steven Chu talk about the warming feedback loop from melting permafrost.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth