Entering the Plastic Vortex

Air Date: Week of July 31, 2009

(Photo: Bagtheplanet)

A pair of research vessels is set to sail to a region of the Pacific Ocean known as the Plastic Vortex, an area of plastic twice the size of Texas that weighs nearly 4 million tons. All of this plastic is killing marine life and toxic chemicals from the plastic waste have the potential to accumulate in the food chain and effect human health. Researchers plan to study and document this plastic soup, as well as test methods for removing the debris and reprocessing it into diesel fuel. Host, Jeff Young, speaks to Mary Crowley and Doug Woodring, founders of this mission called Project Kaisei.

Transcript

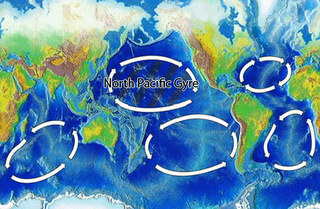

YOUNG: A pair of scientific ships sets sail this month to explore another unusual ocean phenomenon: a giant floating patch of plastic. The currents of the swirling Pacific gyre northeast of Hawaii push some four million tons of plastic into a soupy mass nearly twice the size of Texas. It’s killing marine life and adding to the ocean’s toxic burden.

The Plastic Vortex is located within the North Pacific Gyre, one of the five major oceanic gyres. (Photo: Fangz)

CROWLEY: It’s a pleasure to be on the program.

WOODRING: Great to talk to you today.

YOUNG: Well, first of all, Kaisei – what’s that mean?

CROWLEY: Kaisei means ocean planet in Japanese.

YOUNG: And that’s also the name of the vessel you’ll be sailing on?

CROWLEY: Yes. The Kaisei is 151-foot brigantine and we’ll be sailing with a group of six marine scientists, a group of about five that are there concentrating on capture techniques and what would be the most energy efficient ways of capturing the marine debris and plastics in the ocean.

The Kaisei, a 151-foot brigantine sail boat.

WOODRING: Yes, that’s correct. I’ll be on a research vessel that’s owned by Scripps Institution of Oceanography called the New Horizons. We leave from San Diego and the Kaisei leaves from San Francisco. So we’ll both be in different parts of the gyre and the good part of that is we’re getting a lot of different data points and information from different areas that haven’t been collected before.

YOUNG: So what are the main questions you think we need to answer if we’re gonna find a way to clean this up?

WOODRING: I think the main thing is gonna be how to net it or catch it in an efficient way, ‘cause new technologies exist that allow us to remediate that plastic and actually turn it into a fuel. If we’re able to do that then there’s a value to capturing that product and that can help subsidize a future cleanup effort. So that the trick is really figuring out how much volume we might get and therefore deduct in how much output we could get from a byproduct which is a fuel which could then subsidize our trip.

Mary Crowley on the Kaisei.

CROWLEY: Yes, but this is the sort of thing we’re going to test and find out so we do the best job of it. We’ve really been reaching out to people all around the world about capture techniques and about the idea of doing some passive systems where we would be able to put up netting and use sea anchors going down to a different level. And so we’d be able to use the surface current to bring us the debris. We should be able to fairly easily not involve fish or marine mammals, etc. because the debris doesn’t move except for the current. So it’s quite easy for use to get the debris and not get the ocean life.

YOUNG: Now Doug you mentioned the possibility of converting the plastic into some sort of fuel. But plastics have all sorts of toxin materials in them. How do you convert it to fuel without creating pollution in the process?

WOODRING: Well that’s a great question. And in fact, a problem especially with marine life in the gyre and marine debris is that it also is a bonding agent if you will for heavy metals, persistent organic particles that are in the ocean bind themselves to this material. So not only do you have a plastic particle, but you have millions of small bits of the POPs which are toxic. And the problem here is when the marine life eats this plastic, it may die of inability to digest the material, but it’s also these toxins that are getting into that animal or fish. And when the next animal or fish in the food chain eats that it’s going up into the whole ecosystem including into potentially what we’re eating.

So some of the new technologies that can basically liquefy and refine plastic material back into either a diesel or a heavy fuel, they have an ability to detoxify that in the process. In fact, the way that this system works is if you have a kilo roughly or a pound of plastic being put in the machine, you get about eighty percent of that back in liquid fuel form, about twenty percent is gas form. And that gas is actually going to be used to run the plant itself. So it’s a very, very good new system and there’s a value to the waste wherever it’s collected. That gives people incentive to go collect it.

The Kaisei under the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.

WOODRING: It’s about five days from anywhere.

YOUNG: It’s almost like there’s nowhere no matter how remote you can get in the oceans where you don’t find our trash. It’s amazing.

CROWLEY: It’s very disturbing, but that’s a great deal of why I have such a passion to accomplish this cleanup. It’s sort of like this has happened in my lifetime. And I have a twenty three year old daughter and I have all sorts of young friends and I think their children won’t get to experience the same things I have unless we really take action now and create change in people’s behavior. And we need to figure out effective ways of cleanup and help the ocean. And we need everyone to help us.

YOUNG: Mary Crowley and Doug Woodring, cofounders of Project Kaisei. Thanks very much.

CROWLEY: Well thank you for having us on.

WOODRING: Thank you Jeff.

[MUSIC: Joe Satriani “Clouds race Across The Sky” from The Electric Joe Satriani: An Anthology (Sony Music 2003)]

YOUNG: Coming up – tough choices about energy on the reservation. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth