Clouds Shadow Warming Predictions

Air Date: Week of July 31, 2009

(Photo: Shadiac )

A new study finds that some clouds could make our warming world even warmer. But scientists have had a difficult time understanding the nebulous nature of clouds, and only one climate change model has been able to reproduce the results of the recent findings. Lead author Amy Clement talks with host Jeff Young about what clouds could mean for our end-of the-century forecast.

Transcript

Ralph Waldo Emerson once compared nature to “a mutable cloud, always and never the same.”

Climate scientists trying to understand how nature is changing with global warming find clouds a crucial and frustrating part of the picture. Could clouds get thicker and perhaps offset warming? Or shrink and add to the warming cycle?

A new study on clouds published in the journal, Science, clears things up a bit. And the findings have big implications for just how hot the planet might get. Amy Clement is a co-author. She’s a professor of meteorology and physical oceanography at the University of Miami.

Professor Clement started with decades of data about low-lying clouds over a part of the Pacific.

Amy Clement.

YOUNG: So they’re reflecting some sunlight back up towards space, but they’re not acting like a blanket like some clouds do.

CLEMENT: That’s exactly right, yes.

YOUNG: How do you go about studying clouds? I mean they’re pretty ephemeral things.

CLEMENT: There are two ways of looking at clouds: from below and from above. Sailors have been making measurements of clouds looking up at the sky, determining what fraction of the sky is clouded and writing those down and reporting them back to a centralized archive. And then another way to look at clouds is from satellites. So satellites send down information from the atmosphere in the form of numbers basically, and those numbers are converted into a cloud faction that can then be compared with what a surface observer sees.

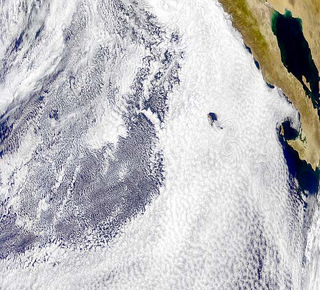

Clouds from above: low-level clouds cover the Pacific off the coast of Baja California, helping cool the climate. (Courtesy of NASA)

CLEMENT: They correlated actually shockingly well. And what we found was that when the surface of the ocean is warm, there is less cloud cover. And we also included in our analysis information about the sunlight that’s being reflected. And what we find is that when the cloud cover is reduced, it lets more sunlight in to the surface and that change is actually largely responsible for the surface warming.

YOUNG: Now a few scientists theorize that clouds might work the other direction – it’s gonna make things cooler. What does your report say about that?

CLEMENT: Well, it’s always possible that they might be right, but the onus is on them to show that there’s an observational support for that happening. Right now the only observational support we have is that as the surface warms, this low cloud cover decreases. And until someone can show the opposite, then we don’t really have any reason to reject that hypothesis.

YOUNG: So what’s going on here with the ocean getting warmer, the cloud cover getting thinner, more sunlight getting down to the ocean and it getting even warmer – it’s kind of a vicious cycle.

CLEMENT: That’s right – sets off a chain of events that actually feeds back on itself. So warming produces cloud cover change, which produces more warming, which produces more cloud cover change.

YOUNG: This does not sound good.

CLEMENT: It’s not. You know there are lots of different processes that operate in the climate system. So this is not the only one, but it does seem to indicate that clouds are an important factor in climate warming.

YOUNG: So what is this mean as we project things forward and we anticipate a more carbon dioxide and greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, more warming – what’s gonna happen?

They might not be pretty, but low-level stratiform clouds help keep the climate cool.(Photo: Andreas Christen)

YOUNG: Really?

CLEMENT: Yeah. And that one – I don’t think it’s a fluke that it was that one. This is the Hadley Centre model from the UK Met Office. They’ve spent a lot of time and effort trying to provide a better representation of the lower part of the atmosphere where these clouds lie.

YOUNG: And what kind of projections does that model generally give us?

CLEMENT: There’s a range of projections of models for the IPCC report which goes from one and a half degrees Celsius to four and a half degrees Celsius for doubling of carbon dioxide which is supposed to happen towards the end of the 21st century. So that’s about three degrees to almost nine degrees Fahrenheit change – a big wide range. The Hadley Centre model predicts a warming of nine degrees Fahrenheit, four and a half degrees Celsius. It—

YOUNG: They’re the ones at the upper end of that range.

CLEMENT: The largest amount of warming of any of the models.

YOUNG: And they’re the only ones that got the clouds right.

CLEMENT: That’s right.

YOUNG: What does this tell us about what part of that range of predictions from models we should really be looking at?

CLEMENT: I think we need to accept the possibility that that top end is not a fluke, that there might be real physical processes that can drive the climate system to that high end of the warming range. The climate system – it’s sensitive. And if we tweak it, we might be looking at a future that’s very different from what we’ve experienced in the rest of human history.

YOUNG: Amy Clement is a Professor of meteorology and physical oceanography and the University of Miami. Thank you very much.

CLEMENT: Thank you very much.

Links

Read the study in the journal Science (subscription required).

To learn more about the Hadley Center’s projections, click here.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth