A Changing South Africa – Part One

Air Date: Week of July 16, 2004

The Wild Coast of South Africa boasts beautiful beaches, sandstone gorges, and a diversity of plants, some found nowhere else in the world. During apartheid, the black homeland of the Transkei in the Wild Coast was passed over by developers and the region stayed relatively isolated. The region stayed pristine but the people living there remained poor. Now, a proposed toll road promises to bring development to the region, but at what cost?

Transcript

Thatched houses called rondavels are scattered throughout Amadiba land. (Photo: Hazel Lum)

Thatched houses called rondavels are scattered throughout Amadiba land. (Photo: Hazel Lum)

CURWOOD: From the wild coast of South Africa, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[BOY WHISTLES AND CALLS FOR COWS]

CURWOOD: As the sun starts to set a young boy of the Amadiba Tribe calls in the cows.

[WHISTLE]

CURWOOD: Nobody here in this community along the Wild Coast of South Africa is in a hurry, least of all the cattle that plod home along paths that have been worn for centuries. This is a place that time has mostly forgotten. The treacherous waters of the Indian Ocean off shore kept European explorers and settlers away, and during the years of racial apartheid, the Wild Coast was isolated in the so-called black homeland of the Transkei. Economic development mostly bypassed this region, and that’s led to some overgrazing of cattle; but, on the whole, there is little environmental degradation.

The Wild Coast still has stunning undisturbed beaches and hundreds of species found nowhere else in the world. But with the arrival of democracy in South Africa, there are new pressures on the fragile balance between humans and nature. The impoverished people here aspire to do more than scratch out a subsistence life based on a porridge made from corn called mealies, and they are making their voices heard.

Zamile Qunya is the chairman of, the Amadiba Coastal Community Trust.

QUNYA: The people are cultivating and find mealies, which is the only food that they have, and also they do fishing. And they were working cutting sugar cane. And we have a very problem of people that are illiterate in our area. So our people are very starving. It’s the poorest of the poor. There are people that live with no food in my area.

CURWOOD: South Africa is the richest country in Africa, with an economy that is two thirds of the entire continent. Cities such as Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban have glittering malls, plenty of fast cars and luxurious homes.

The people here on the Wild Coast would like to share in the bounty, but they have some choices to make. One path would take them in the direction of development that would sustain their rich traditional Xhosa culture and unique ecology. Another would simply trade their economic hardships for the impoverishment of their environment and culture.

Already the natural geology and beauty of the Wild Coast is attracting developers who see the potential of profits in bringing highways, mines, hotels and casinos. As an alternative, the Coastal Trust began an experiment with eco-tourism in 1997.

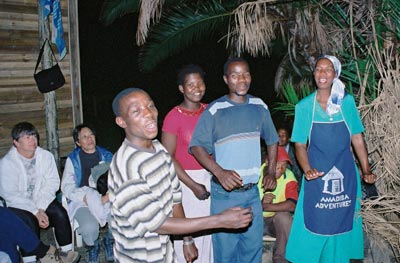

[SINGING AND CLAPPING]

CURWOOD: Around the fire at the Kwanyana campground, workers for the community eco-tourism project called Amadiba Adventures are sharing dances, songs and stories with their tourist visitors. This song is about learning not to fear the baboons, which can be ferociously pesky in their quest for food. The singers stomp in place around a circle, gyrating their arms and torsos in a monkey-like motion. [BABOON SONG UP AND UNDER]  Kwanyana camp crew (Photo: Karen Wildfoerster) Kwanyana camp crew (Photo: Karen Wildfoerster)

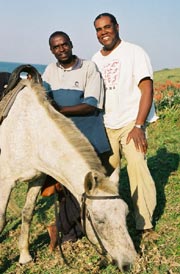

CURWOOD: The idea behind the Amadiba Adventures tours is simple: Get folks who like the outdoors to come and camp, hike, canoe and horseback ride in this unique ecosystem and it will generate jobs. Getting started wasn’t easy. [CRICKETS UP AND UNDER] CURWOOD: When a white man named Simon Speering, who enjoyed hiking in the area, brought the idea of eco-tourism to the tribe 1997, he was met with a lot of suspicion. But once the Amadiba tribe set up a trust with local ownership and control, Lindele Mxhuma, a guide for Amadiba Adventures says, local people became enthusiastic. MXHUMA: Because they see that it gave them some money in the beginning. So they were happy to see it happening here. And they have seen that no one took their land away as they thought. People come and see our rivers and bays and they pay for just seeing all those things and then they go back home, not damaging anything. CURWOOD: Lindele’s work is to shepherd visitors along the Wild Coast on horseback and on foot. Part of his job is sharing his culture, like telling stories about playing games and tending cattle as a Xhosa boy. MXHUMA: There are so many things that you did as boys, you know. When you are looking after the cows the other boys that were older than us, they used to come to us and make us fight each other, you know. What they did, they used to put a stick between you and the other boy. If that boy jumps the stick, then you have to fight because they will say he has defeated you, so you have to fight. If he comes across the stick you have to fight until he goes back. But not big fights, no. Just fights for boys, you know. We didn’t have grudges for that. [FOOTFALLS, CONVERSATION]  Lindele's family (Photo: Steve Curwood) Lindele's family (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: Lindele’s father’s home is sometimes a part of the Amadiba Adventure experience. Visitors sleep at the compound, which has several round huts with thatched roofs, whitewashed walls and dirt floors, and a small square house for dining. There’s no sanitation beyond an outhouse, no easy access to fresh water or medical care or schools, and no lights beyond candles that they are lucky enough to afford, thanks to their modest income from the tourism project. [CHICKENS PEEPING] CURWOOD: But Lindele’s family is among only a fortunate few, observes Amadiba Trust chairman Zamile Qunya. Seven years into the tourism project, despite a stream of business from South African and European tourists, there are still no jobs for the vast majority of people here and he is disillusioned.

QUNYA: But I must tell you the reality fact as a chairperson, and everybody will support me: there was no big impact in terms of job employment, in terms of spin-off that the tourism has created other jobs. What we are doing is that most of the people that are working in tourism as the tour guide, they are part-time and they are small people that can cook because of the tourists arriving. But they didn’t make any big impact in terms of the poverty we have and the population we have. CURWOOD: So to bring more jobs and income to the area, Mr. Qunya tells me he has become a proponent of a project to build a highway that would link the cities of Durban and East London with a high-speed toll road. He has some powerful allies who agree. OLVER: The Transkei itself has been historically very underdeveloped. It's an area with the highest levels of poverty in South Africa and the lowest levels of infrastructure. CURWOOD: Crispian Olver is the Director-general of Environment and Tourism for South Africa. OLVER: You know, for a long time government has been wanting to bring development to that area. And the best strategy for doing it that government has come up with is linking this development corridor to the north and the development corridor to the south, and, in a sense, creating an eco-tourism route that will then bring jobs and bring investments to Transkei. And, in particular, along the coast, to the wild coast. CURWOOD: But the idea is steeped in controversy. For a while there was a debate over whether major parts of the largely pristine Wild Coast should become a national park. That discussion is now on hold, but the concerns that gave rise to the proposal are still very much on some people’s minds. South Africa is one of the three most biologically diverse nations on earth, with many endemic species -- that is, those that are found nowhere else. In fact, the World Wildlife Fund lists this part of the Wild Coast, known as Pondoland, as a critically endangered global hot spot. Cathy Kay is National Director of Conservation for the Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa, the largest environmental organization in the country. She says putting a toll road through this sensitive part of the Wild Coast doesn’t make sense.  Cathy Kay Cathy Kay

KAY: It’s the heart of the Pondoland Center of Endemism and was recognized by Conservation International at the World Parks Congress for its uniqueness, for its biodiversity and its plant species. CURWOOD: For example, what’s in the biodiversity here that’s of so much import? KAY: You certainly have flora that is found nowhere else in the world. You have the Pondoland’s Tea Man’s Bush which is over a thousand years old, growing in some of these valleys. We have brand new species of plants that haven’t even been given names yet. CURWOOD: Just to the north of the Wild Coast, the beaches are crowded with hotels, condos and casinos. And while most of the new toll road would follow the present alignment of a two-lane road far away from coast, an 85-kilometer section would slice right through critical coastal habitat. KAY: The only bit that we’re complaining about is this 85 kilometers. CURWOOD: Again, Cathy Kay . KAY: For the rest of the other 85 percent of the road, we have no problem. It’s only this 15 percent that we’re saying, “if you bring it this close to the coastline, what you’re going to have is another south coast” which is across the river from here where there’s solid wall-to-wall concrete right along our primary dunes, right across our estuaries and it’s actually destroyed the aesthetics of the coast. CURWOOD: But Zamile Qunya of the Amadiba Trust says building the road would pay social and economic dividends for years to come. QUNYA: We don’t have any industry, any factory in Transkei. So starting to put a road, which you make an access to, you will build garage, you will create a lot of employment. We are saying now to the people, even the environmentalists, they must compare and balance the issue of social needs and the issue of animals and trees. They must not be biased on trees and animals. They need to balance it because we like trees and animals to be there, but you need to balance with the poverty along the coast. CURWOOD: Zamile Qunya also favors another proposal to bring jobs and income to the area: a mine that would dig out the titanium and other valuable minerals that have been found in the red sand dunes just inland from some of the most spectacular beaches. The Environment and Tourism Ministry opposes the mining, which they say could pollute the estuaries and threaten the area with sprawling shantytown development with people who come looking for work. Mining might create 700 jobs that would be lost when the minerals run out, according Environment and Tourism Director General Crispin Olver, as opposed to the 9,000 tourism jobs that he says the area could sustain over the long haul. Still, he cites the bid to put in a mine as an urgent reason to find alternate means of development, including a toll road and more tourism. OLVER: A solution that doesn't address poverty is ultimately going to lead to the entire erosion of the environment in that area. So, you know, one has to come up with a development strategy. The question is what development strategy. And for me, the basic choice on the Wild Coast is are we able to put an eco-tourism strategy on the table that works and brings jobs and brings investment into the area? Or are we going to allow alternative strategies like mining -- or I know there are a couple of agricultural proposals -- allow those strategies to go ahead? But it's going to be one or the other. [CRICKETS]  Steve Curwood and guide Lindile Mxhuma Steve Curwood and guide Lindile Mxhuma

CURWOOD: Lindele Mxhuma, the tour guide, feels strongly about what he expects would happen if the mine comes. MXHUMA: This project that we have here will die. Definitely, it will die if the mining come here. Tourism and mining don’t go together. CURWOOD: And what about putting a toll road through the Pondoland Wild Coast? MXHUMA: Yeah, I don’t think that would be a good idea or a bad idea. You know, I’m neutral. What makes me neutral is that yeah, we do need the road, but we don’t need it very close to the coast. [SINGING] CURWOOD: We’ll take a closer look at the biological diversity of Pondoland and find out more about the eco-tourism project involving Lindele and the Amadiba Trust just ahead, so stick around. I’m Steve Curwood and you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth. Links

|

Zamile Qunya (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

Zamile Qunya (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)