November 21, 2025

Air Date: November 21, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Tropical Forests, Forever?

View the page for this story

As the host of this year’s UN climate treaty negotiations and home to most of the Amazon tropical rainforest, Brazil led a major advance for forests and their indigenous inhabitants called the Tropical Forest Forever Facility. The new $125 billion fund, with guarantees for investors, will send its profits to countries with documented forest preservation, including some cash going directly to indigenous and local populations. Michael Coe, a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center who was at COP30, joins Hosts Steve Curwood and Jenni Doering to explain why forest protection is a vital piece of stabilizing the climate. (11:30)

Air Pollution Pioneers

View the page for this story

We now know about the severe health impacts of tiny airborne particles or PM2.5, thanks in large part to the groundbreaking “Six Cities” study that started in the 1970s. The leaders of that team were Doug Dockery, who became chair of Environmental Health at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and Arden Pope, now a distinguished professor of agricultural economics at Brigham Young University. They are co-authors of the 2025 book, Particles of Truth: A Story of Discovery, Controversy, and the Fight for Healthy Air, and they share with Host Steve Curwood the story of how they undertook their vital research and the industry pushback they received. (20:31)

Thanksgiving Feast Favorites

View the page for this story

To kick off this Living on Earth Thanksgiving special, members of our crew share a few laughs and our favorite Thanksgiving recipes, from pumpkin soup to chouriço stuffing to desserts made with leftover pie crust. (14:28)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

251121 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Michael Coe, Doug Dockery, Arden Pope

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The COP30 climate summit launches a new plan to protect tropical forests.

COE: These forests are extremely important for our stable climate. They are going to mitigate some of the worst impacts of climate change occurring because of fossil fuels, and we are eliminating that incredible gift.

CURWOOD: Also, the story of the groundbreaking Six Cities study that revealed the deadly dangers of air pollution.

POPE: What we found is that there was about a 25% increase in mortality risk from just breathing, and of course everybody breathes, and so the results implied that air pollution in the more polluted cities were contributing as much to attributable mortality as even cigarette smoking.

CURWOOD: And we gather around for some Thanksgiving feast favorites. That’s this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Tropical Forests, Forever?

Tropical lowland forest in Mount Tupalao in the Philippines. About forty percent of the tropical forest in Southeast Asia has been lost due to deforestation and degradation. (Photo: Firth m, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

For the first time 30 years, Brazil was the host of the UN Climate Treaty negotiations known this year as COP 30. And it’s no surprise that the country with most of the Amazon tropical rainforest led a major advance for forests and their indigenous inhabitants.

DOERING: There have been other attempts to incentivize protecting forests, including carbon offsets, but these have been vulnerable to fraud and have had limited success. So, through the COP, Brazil, Norway and the Netherlands seeded a new $125 billion fund with guarantees for investors that will send its profits to countries with documented forest preservation, including some cash going directly to indigenous and local populations.

CURWOOD: For more on this critical ecosystem and the impact of the Tropical Forest Forever Fund or Facility, we called up Michael Coe who was at the COP in Belém Brazil. He is a Senior Scientist and tropical forest expert at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. Welcome to Living on Earth!

COE: Thank you very much, Stephen.

DOERING: So Mike, can you please give us a sense of the state of the world's forests, and especially tropical forests, at this moment? Where are they, and just how much of them have we lost?

COE: You know, there's three big blocks of tropical forest. It's in South America, Southeast Asia and the Congo. And when we think about really, over the last only few decades, a tremendous amount those have been lost. The greatest amount of loss is in Southeast Asia, where something like 40% have been removed. South America, something like 17%, and the Congo, about 20%. So in each of these regions over the last few decades, there's been significant loss of forest, and most of that, of course, is for agriculture.

CURWOOD: So Mike, tell us why tropical forests are so crucial. What's their role in the climate system and beyond?

Tropical forest in the Xingu Indigenous reserve in central Mato Grosso, Brazil. Tropical forests not only sequester carbon, they also act as planetary cooling “air conditioners” by pulling water from the soil and releasing it into the air as water vapor. (Photo: Michael Coe)

COE: They are really fascinating for the climate system. We think mostly about them in terms of their carbon. You know, they have an enormous amount of carbon in them, so when you deforest, you're emitting a great deal. But what I have been interested in, and what's really fascinating, is that that's not the only reason they're great for climate. Another big part is they are just giant air conditioners. What they do is pull water out of the soil from very deep down, and they evaporate it. And when they're photosynthesizing, they're evaporating water. And when you evaporate water, that's energy. You're taking heat, and you're converting water to vapor, and you're carting it away. So what they do is they cool the land surface enormously. And we see this throughout the tropics. If you deforest a parcel of land, it will almost immediately something like five degrees C warmer than the forest right next door, and that's on annual average. So if you walk out of the forest in the dry season, and you walk out onto an open field that is fallow, it is 10 degrees C hotter, 15 degrees C hotter. It is just astounding how much, and that's not just a local effect, but it has global implications.

DOERING: It's almost like the forest is able to sweat like we do.

COE: It's really exactly what it is. When it's photosynthesizing, it has to use that water to cool itself off. It's pulling in sunlight and it's getting hot. So that's exactly what it does.

CURWOOD: Well, just how much are deforestation and the degradation of forest adding to the climate emergency every year? I mean, compared to the burning of fossil fuels, what percentage of the problem are we looking at here?

COE: It's big. When you say tropical forest, it might be, say, 10% of all emissions, human emissions. If you talk all forest on the planet, probably 20% of all emissions. So deforestation is a big number. For many nations, it's by far the largest. And China's number one in emissions. US is number two. Deforestation is number three.

Deforestation in eastern Mato Grosso, Brazil. Deforestation of tropical forests, typically for agricultural purposes, is responsible for about 10% of all global emissions. (Photo: Michael Coe)

CURWOOD: And we talk about the carbon that it sequesters, but what about when you cut those trees down? How much carbon does it stop taking out of the air? What's the loss there and the effect on the climate?

COE: You know, that's a big number. You're talking about something like 15% of human emissions are being pulled back out by forests, by tropical forests. So yeah, it's a double loss. You're shutting off this ability to pull CO2 out of the atmosphere, and then you're just putting more back in. So it's a big loss.

CURWOOD: Wow. So at the end of the day, you have a 20% loss by cutting them down, and then you have another 20% loss of the forest pulling it out of the atmosphere?

COE: More or less, yes. I mean, that's what you're doing. You're shutting off your ability to pull it out, and you're emitting. So this is why, you know, some studies have shown that portions in the Amazon are now net emitters of CO2. Instead of net pulling it out, they're actually emitting more than they're pulling out, and that's because deforestation and the fires that are occurring.

DOERING: And by the way, I think we've been referring to deforestation, also to forest degradation. What does that actually mean?

COE: So forest degradation is when you still have the forest in place, but what you're doing is degrading how much carbon it has in it, basically how many trees.

CURWOOD: What leads to forests being so degraded, even if they're not completely cut down?

COE: The number one source of degradation in the tropics is fire. And the thing about fire, I can say this for sure in the Amazon and in Congo, in these dense, wet forests, fire is not natural. It doesn't occur like it does in the boreal forests, where lightning strikes and a huge fire occurs. That does not occur in the tropics. These are fires lit by people. So they're burning pasture to rejuvenate the grasses. They're doing slash and burn so they can open land to plant rice or whatever. And so in many ways, it is a problem that can be addressed. We know it's being caused by humans. And this is one of the things we try to work on a lot in Brazil in particular, is how do we reduce fires? The land is chopped up into chunks, and those edges now are really susceptible fire, and fire goes in there and takes out a large fraction. Once you've done that, it's a cycle. Now there's more sunlight coming in, it gets hotter, it's more susceptible to fire. And so it's a pretty slippery slope once you get started.

CURWOOD: And by the way, to what extent are those fires related to the warming planet itself?

Burning fields near Yangambi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Fire is the number one cause of degradation in tropical forests. (Photo: CIFOR-ICRAF, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

COE: A great deal. And so last year was an incredible example. It was an El Niño year, which meant it was hotter, much hotter and drier. So when fires did start, they got huge. And it looks like last year, degradation committed as much CO2 to the atmosphere as deforestation did.

DOERING: Wow.

COE: So in most years, degradation's a significant number, but it's not as big as deforestation, you know. So it just essentially doubled the amount of CO2 emitted last year.

DOERING: And by the way, just how important are tropical forests to the Earth's temperature? I mean, if we cut down all tropical forests, what do you think would happen to the global average temperature?

COE: That's something we've been trying to quantify for a very long time, and recently, we did some experiments and put some work together, and we found that if you cut down all the tropical forests, every one, then the global temperature would probably rise by about one degree C, which is a large number. And what's really fascinating about that is half of that one degree C would be from all the emissions, the CO2 emissions, but the other half would be from that air conditioner that we broke. Those forests, as I mentioned before, they're an air conditioner, and they cool the planet. What's important here also to think about is okay, that means, if we deforest 10%, we raise the temperature by point one degrees C, which we really can't afford.

DOERING: Every tenth of a degree matters.

COE: Every one.

CURWOOD: So Michael, I know it's really hard to account for all of this, but it sounds like the problem with forests, tropical forests, them getting cut down and also being degraded, we're looking at a huge portion of the climate emergency. Looks like it's north of 30% or more that could be happening here.

COE: It's a big number. These forests are extremely important for our stable climate, and it’s one of the things we keep saying is they are going to mitigate some of the worst impacts of climate change occurring because of fossil fuels, and we are eliminating that, that incredible gift.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (left) and UN Secretary-General António Guterres (right) attend the launch of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility. The TFFF is an investment fund designed to pay countries as well as local and indigenous persons for verified maintenance of their tropical forests. (Photo: Kiara Worth, UN Climate Change, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: So we're speaking to you at COP30 during its last days, and there's been a proposal led by Brazil for this Tropical Forest Forever Facility to fund, to pay to keep the trees. This is different from the question of money for carbon offsets, where money is given to countries to say, well, keep the trees from burning. In this case, they're talking about setting up, I don't know if it's a bank or an insurance policy that if a country shows that it hasn't cut its trees, it will get some money, very different. How can you police such a thing?

COE: It's going to depend on satellite observations of forest cover, because it has to be applied uniformly everywhere. We can't have independent agencies for every nation reporting. What we have to have is one tool that will tell us, and we all have to agree that that works.

DOERING: I mean, that seems like it could get tricky in terms of, what's the definition of healthy forest, and how do you tell if a forest, you know, has been slightly degraded, and then it starts being degraded more, and it, where's that tipping point, I guess, where's that, you know, slippery slope?

COE: That is tricky. And again, I think this TFFF has been, is being launched, and it's, I think it's a great idea. The devil will be in the details. And those details have not been worked out. You know, it's a process, and making those decisions on what constitutes full forest, et cetera, et cetera still have not been made.

DOERING: And by the way, what's in it for the people who are putting in money up front for this, what's the payout that they're going to receive?

COE: It's a fund, so it's going to be invested. And from my understanding, then that means that there's a certain rate that goes to the investors, and there's a certain amount then that is set aside to go to the nations to pay for their forest. You know, there's the positive of that is because now, if you're not buying a credit, other players, other investors can get involved, say pension funds or insurance companies who aren't necessarily interested in offsetting carbon, they're interested in making a profit. So it brings other actors into the forest conservation realm.

Forest ecologist Dr. Michael Coe is a Senior Scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. He attended the COP30 climate talks in Belém, Brazil. (Photo: Sarah Moore)

CURWOOD: You know, it appears to me a unique aspect of this is it's talking about some percentage of these funds being paid directly to indigenous peoples and local communities. How big a deal is this?

COE: That's a big deal. Up to this point, it's been very difficult to find ways to include indigenous groups in the classic carbon credits, et cetera. So this whole idea is just very different. Instead of buying a credit, you're investing in a fund, and part of the profit of that fund goes to these nations for keeping forests in place, and part of that goes to people on the ground.

CURWOOD: So we know that this tropical forest fund is in its early stages. There seems to be 5 or maybe $7 billion committed at a seed level. How excited are you about the possibilities of this fund?

COE: I'm actually very excited. This is a significant amount of money. I think that the way it's structured will attract more investors. I think there's a real possibility here that this could fund significant conservation.

CURWOOD: So Mike, you're at COP30 right now. You've been going since the big meeting in Copenhagen back in 2009, and you've been in this business of climate research for a long time. What has the mood been like this year at the summit, and how are you feeling about the future?

COE: For me, this is, the mood here is wonderful. We've been trying for years to get forests, tropical forests in particular, as part of the agenda. Here in Brazil at COP30, they're really front and center. Forests are clearly an important part of our strategy. So for me, it's very positive. And you know, in terms of the future, I, it's a long slog we're on here. We have to keep trying, and we have to keep working and trying. This climate problem is not going to end tomorrow, and so these negotiations, these meetings, are extremely important.

DOERING: Dr. Michael Coe is a Senior Scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center.

CURWOOD: And he's been on the line with us from Belém in Brazil at COP30. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today, Mike.

COE: And thank you. It's been an absolute pleasure.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Tropical Forest Forever Facility

- Learn more about Dr. Michael Coe’s work

- Learn more about the Woodwell Climate Research Center’s research on tropical forests

[MUSIC: El Búho, Uji, Barrio Lindo, “Xica Xica” on Balance, Wonderwheel Recordings]

DOERING: Coming up, two of the pioneering researchers who found air pollution can be as deadly for some populations overall as cigarette smoking, just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: El Búho, Uji, Barrio Lindo, “Xica Xica” on Balance, Wonderwheel Recordings]

Air Pollution Pioneers

The Geneva Steel Mill in Utah Valley in 1989. The temporary closure of the mill on August 1, 1986 produced a natural experiment that allowed Dr. Arden Pope to show how air pollution doubled and at times tripled hospital admissions of children after the plant reopened on September 1, 1987. (Photo: Arden Pope)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

When you take a breath, an invisible poison may be entering your lungs alongside the oxygen you need. Tiny particles from burning everything from fossil fuels to forests can get deep into your lungs and even your bloodstream, exposing you to toxics like heavy metals and sulfates. We now know about the dangers of these particles, also called PM 2.5, but we were mostly in the dark about the scale of the problem and just how deadly air pollution could be until the 1970s. That’s when a team of researchers began the Six Cities study, which ultimately brought air pollution to the forefront of public health. The leaders of that team were Doug Dockery, who became chair of Environmental Health at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and Arden Pope, now a distinguished professor of agricultural economics at Brigham Young University. These two pioneering researchers who documented the health effects of air pollution are co-authors of the 2025 book, Particles of Truth: A Story of Discovery, Controversy, and the Fight for Healthy Air. Welcome to Living on Earth, Arden and Doug!

POPE: Thank you. We're glad to be here.

DOCKERY: Great to see you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Now breakthrough research often begins with some serendipity. So Arden Pope, please tell us what you observed and researched that kind of started much of this.

POPE: Well, for me, it started back in the 1980s, late 1980s when a steel mill in our local valley shut down for 13 months and reopened. And this actually produced a very interesting natural experiment where we could look at the changes in air pollution when the mill shut down, and we could also look at changes in pediatric respiratory hospital admissions. And although I was not really doing air pollution research at the time, this was such an interesting and unique natural experiment that I took advantage of it. The results were really quite dramatic. The air pollution from the local steel mill did appear to contribute not only a lot of pollution, but contributed to respiratory illness in children, and so I published that work, it caused kind of a local stir, as well as a generated interest by other researchers that were doing air pollution research, including Doug, and that just sort of led to ongoing efforts to further understand air pollution and its impact on health, and it's, it ended up being a career I never really planned, but it's been a good career.

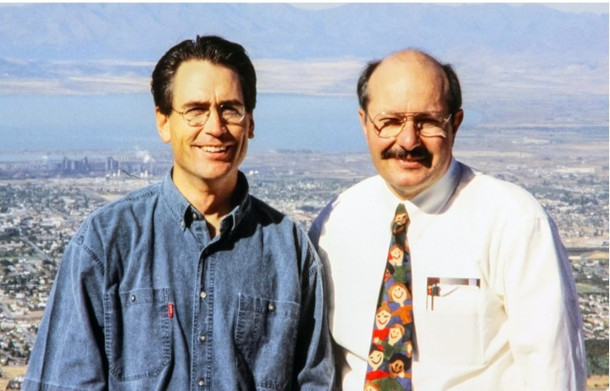

Dr. Arden Pope (left) and Dr. Doug Dockery (right) circa 1995, with Utah Valley and the Geneva Steel Mill in the background. Dr. Pope’s paper on the health effects of air pollution from the mill caught Dr. Dockery’s attention, leading to nearly four decades of collaboration. (Photo: Doug Dockery and Arden Pope)

CURWOOD: What were the health effects that seemed to have affected children?

POPE: The initial health effects that we observed were, were fairly straightforward. It was hospital admissions for respiratory disease in children, but follow up studies, some of them that I did with Doug and his colleagues at Harvard, found that the air pollution contributed to respiratory symptoms, reduced lung function, and then ultimately, as we started studying this more, we could see changes in mortality counts across time, both for respiratory disease and cardiovascular disease. So it was really quite striking.

CURWOOD: And Doug Dockery, how did you get together with Arden Pope and begin what led you to study the health effects of air pollution?

DOCKERY: We had been conducting a study in six cities across the United States for more than a decade when Arden's paper came out, and examining the effects of air pollution on respiratory health of children and adults. And when Arden's paper appeared, I got a call from a reporter who asked me to comment on it, and I had went back and read the paper, and I was just astounded at what an elegant study design it was. We had always wanted to do the type of experimental study where, what happens if you turn off air pollution? Can you see the benefits of that? And in fact, here he had this natural experiment and showing that when you did dramatically decrease the air pollution levels, you could see respiratory benefits of that. So we got in touch with each other. After that, Arden came to me and said, you know, I'm just an economist, I really don't know what's going on here. I have no experience in doing this. I'm getting beaten up by the local press about this, and I really need some help. And so we sat down, and I invited him to come to Harvard to make a presentation about his results, and we sat down and designed some follow up studies to strengthen the evidence from the work that he was doing, and that led to him coming to Boston on a sabbatical, and led to a long term collaboration we've had over the past 40 years.

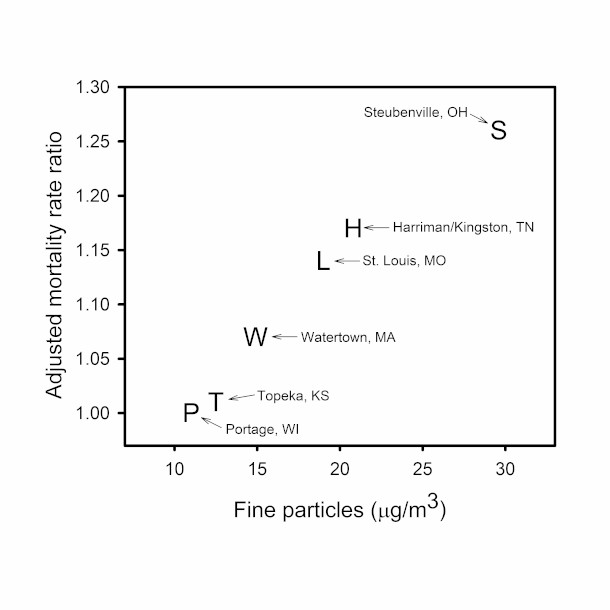

Estimated adjusted mortality rate ratios plotted over mean concentrations of PM2.5 from the original Harvard Six Cities study. The Harvard Six Cities Study published in 1993 in the New England Journal of Medicine revolutionized the field of environmental health, linking chronic exposure to fine particulate air pollution to increased mortality and shorter life expectancy. (Photo: Figure 4.1 in Particles of Truth. Adapted and replotted from results reported in Dockery et al. An Association between Air Pollution and Mortality in Six U.S. Cities, NEJM 329, no. 24 (1993): 1753-1759.)

CURWOOD: Harvard environmental health professor Douglas Dockery recalls that after meeting Brigham Young statistician and professor C. Arden Pope and learning of his work they set on a path of discovery which would lead to one of the biggest breakthroughs in modern environmental health. And it started back in 1973 with the Arab oil embargo raising prices and cutting supplies. The US government decided America should reduce the risk of imported oil by looking more to the abundant source of domestic energy, coal. And with the burning of coal comes a lot of air pollution. So, the Harvard team, including John Spengler, a co-chair of the World Media Foundation, which produces Living in Earth, wrote and won a federal grant in 1974 to research the impact of dirty air on respiratory health. They chose six US cities to study: Portage Wisconsin and Topeka, Kansas with relatively clean air, Watertown Massachusetts and St Louis Missouri with moderate pollution, and Harriman/Kingston Tennessee and Steubenville Ohio, which were downwind of nearby coal-fired plants. All six of these cities were in white and mostly middle-income census tracts, avoiding possible confounding variables of diverse ethnicity and economic status. In 1989 Dockery and Pope first learned of each other’s work when they were interviewed by Science News reporter Janet Raloff. They then combined forces and Pope came for a sabbatical term at Harvard. That began years of deep analysis that revealed they had a large data set showing that health effects from air pollution went well beyond its respiratory risks. Again, followed by Brigham Young professor Arden Pope, here’s Harvard professor Douglas Dockery describing the evolution of the Six Cities study.

DOCKERY: And we were following adults and kids in these communities with yearly examinations of their lung function and respiratory symptoms with the expectation that we would be seeing changes in their respiratory health. And ultimately, we did see those changes, but in the early 1990s, there was also evidence that when air pollution went up, we could see increases in daily mortality. And this raised the question, well, could we also see those effects on long term changes in life expectancy. In the communities with higher air pollution, we did in fact see shorter life expectancy by several years, in a fashion that really was very linear and very associated with these fine particle levels, what we now call PM2.5. And these are very substantial effects, much bigger than we expected, all in communities that at that time, were meeting the current air pollution standards to protect the public health.

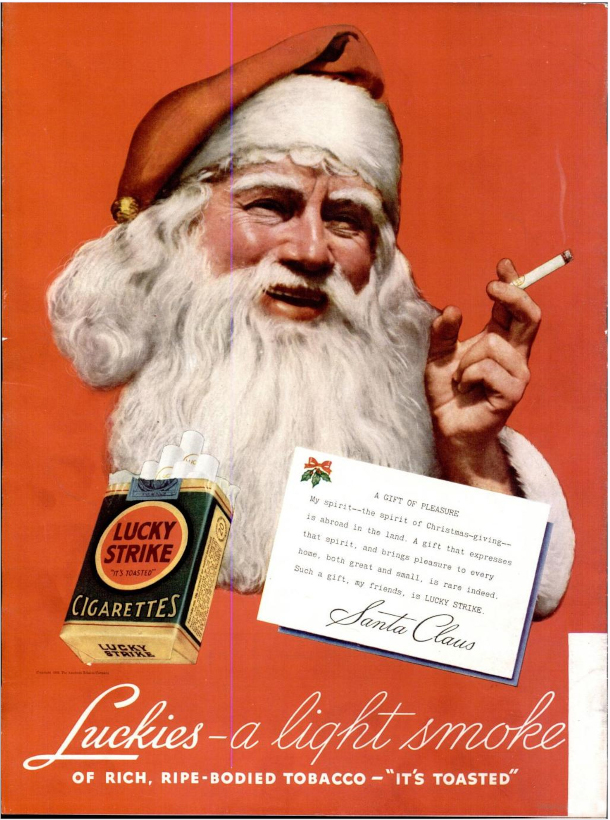

Lucky Strike cigarettes advertisement in Life magazine, 1936. The Harvard Six Cities study showed that on a population-wide basis air pollution in more polluted cities was contributing as much to attributable mortality as the fraction of people who smoked cigarettes. (Photo: Anton Rath, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: What kind of numbers were you talking about? What did you find in that first go around that surprised you? Arden?

POPE: I mean what we found is that in the most polluted city, there was about a 25 to 30% increase in mortality risk. Now that was stunning, because cigarette smokers at the time we knew that there was about 100% increase in mortality risk, but only about 25% smoked. But what we found is that there was about a 25% increase in mortality risk from just breathing. And of course, everybody breathes, and so the results implied that air pollution in the more polluted cities were contributing as much to attributable mortality as even cigarette smoking.

CURWOOD: Doug?

DOCKERY: We found that life expectancy was about two years shorter in the communities with higher air pollution. And put that in context, if you cured all cancers in the United States, the net effect on life expectancy in the population would be about two years. So we were talking about a identifiable risk factor here, air pollution, that was as big as all the effects of cancer, and that was very sobering to us at that time, especially considering that these were all communities that were meeting the air quality standards for public health at that time. I mean, we were stunned by this and knew we had to replicate these results. As Frank Speiser said at that time, this is not going to pass the laugh test if we put this out in a journal without validating this.

CURWOOD: And Arden Pope, your work shows a lot about the global burden of disease. Just how big a deal is this around the world, getting exposed to PM2.5?

Naples, Italy, in January 2025. The Global Burden of Disease Research Group estimates that fine particle air pollution contributes more to burden of disease than any other environmental risk factor and is in the top 10 of all risk factors contributing to disease and death globally. (Photo: keppet, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

POPE: So it's a big deal. In the United States we see these effects that Doug and I have been talking about, but the pollution in the United States is actually relatively low compared to exposures in many other parts of the world, China, India and other places. If you take the studies that we and others have done looking at the long term exposures to air pollution, and you use the results from those studies and apply it to exposures that people are exposed to around the world, you can estimate the global burden of disease, and this has been done by the Global Burden of Disease Research Group, and they estimate that fine particle air pollution contributes more to burden of disease than any other environmental risk factor, and is in the top 10, sometimes even in the top 5 of all risk factors contributing to disease and death. So it's a remarkably large impact. And I think Doug and I started working together nearly 40 years ago, and I don't think either one of us even imagined that air pollution was that large of a contributor to disease and death.

CURWOOD: Yeah, you have a chart in your book that says that this is more hazardous to global health than terrorism, car crashes, all kinds of things that we think of, infectious disease, kind of mind boggling, it feels like.

POPE: Yeah, I agree. I mean, it's been a big surprise to me that it has that large of an effect, and part of that's because these fine particles do have a lot of toxic materials, and they do contribute to both cardiovascular and respiratory as well as lung cancer. But the other thing is, is the exposure is so ubiquitous, pretty much everybody is exposed to this pollution, and in some parts of the world, the exposure is really remarkably high.

When the Harvard Six Cities Study was published in 1993, the Environmental Protection Agency was proposing a new standard for PM2.5, which would have required industry to reduce their emissions. (Photo: Texas GOP Vote, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Doug, the Harvard Six Cities study caused quite a backlash from various actors, particularly industry. In fact, I think you were accosted by protesters one time, and you went to Capitol Hill to testify about this. What happened?

DOCKERY: I had been invited to testify at a Senate hearing on air pollution, and in fact, had actually taken the train down from Boston and got off at Union Station. And then you walk up the hill to Capitol Hill to the Senate office building. And as I was coming up the hill, I encountered a group of people in white coats and funny glasses and holding signs with, "show us the data." And I was intrigued, and went up to see what they were about, and found they were actually demanding the data from the Harvard Six Cities study. And it was really the first episode I'd encountered where we were being challenged like this. And it turned out that this was a demonstration that had been organized by the Center for Sound Economy, which was funded by the Koch brothers, to protest our work. And it follows the example of demands that have been developing to undermine epidemiology studies by demanding release of potentially personal data from the participants in our study.

CURWOOD: They charge that you were conducting "secret science." What the heck is that? And why is such an allegation designed to make human health research impossible from your perspective, Doug?

Charles Koch in 2019. Charles G. Koch and his brother David H. Koch funded organizations like the Center for Sound Economy, which sought to discredit the Harvard Six Cities study. (Photo: Gavin Peters, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DOCKERY: Well, of course, when we approached people to be participants in our study, we said we would keep their information confidential. So various groups came forward and said, well, we can only believe these data if we get to analyze them ourselves. And so we certainly made a practice of making data available to other investigators to analyze or reanalyze the data, but not to the extent that it would be identifiable as individuals and potentially compromise the assurances of confidentiality that we had agreed to.

CURWOOD: So Arden, what's going on here? What do you think this charge of "secret science," and I gather you guys were hit with a bunch of subpoenas and from the Congress and such, what do you think they were trying to do here?

POPE: Well, it was very clear that there were these special interests that did not want to see these studies used to result in stronger regulations for air pollution, stronger standards for PM2.5. In fact, shortly after the Harvard Six Cities study and related studies were published in the mid 1990s, the EPA was proposing a new standard for PM2.5 that would require industry and other polluting sources to reduce their emissions. And so it's way easier to make a lot of money if you don't have to pay part of your costs. And part of the costs of burning fossil fuels are these health costs that we were observing, and so one way to try to avoid those costs is to simply deny them. And that seemed to be what was going on, and I think is still going on to some degree.

CURWOOD: And by the way, I think some of the folks who brought actions, even some litigation, states like West Virginia, for example, are still doing that when it comes to climate disruption.

POPE: Yeah, the sort of strategies to deny this research were developed actually to discredit some of the studies with regards to cigarette smoking. These strategies have been used to deny the effects of air pollution and also deny the effects of the greenhouse gasses and the impact on, on our climate.

CURWOOD: So obviously, Six Cities study is a big deal and comes under attack. How was it backed up by subsequent research?

The 2025 Palisades fire in Los Angeles. Our guest Dr. Doug Dockery warns that pollution from wildfires will continue to threaten public health. (Photo: Frank Kovalchek, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

POPE: When we got the results, at least the initial results from the Harvard Six Cities study, we were as surprised as anybody. We did not expect to see such large impacts of air pollution on respiratory and cardiovascular disease mortality. And so we actually contacted the American Cancer Society, collaborated with them to use another big, large cohort that they had been following so that we could see if we could replicate the results of the Harvard Six Cities study. And in fact, in general, we were able to replicate those results. And so we published the results of both of those studies back in the mid 1990s and then even both of those were criticized. And then we actually cooperated with the Health Effects Institute and a research team that did a big reanalysis of both of those studies to see if they could replicate the results, see how robust they were. And in fact, they replicated the results and found that they were remarkably robust. And then since that time, there have been many other cohorts that have been analyzed, the US, in Canada, in Europe, in China, and in general, they are finding basically similar results.

CURWOOD: So Doug, where are we in terms of improving air quality, both here in the United States and around the world? I think around the world, deaths from particulates are on the scale of like 7 million a year excess deaths. What extent have we made significant strides, and what can we do to bring those numbers down?

DOCKERY: Well, I think there is a positive story here in that when you compare air pollution now to where we were 40 years ago when we started this research, we've seen very, very substantial improvements in air quality across the United States, but we're still seeing effects, for example, of uncontrolled wildfires impacting large parts of the United States. Internationally, there's been recognition of where the high air pollution levels are, particularly with the use of satellite data, which provides information on areas where there was no monitoring before. And so we recognize now, in Africa, in Southeast Asia, in China, the very, very high concentrations that existed before there. But also this has brought pressure on the local governments to actually take some action. So we are seeing progress around the world as it's been recognized, that these are preventable health effects, and there is a real opportunity to have substantial benefits from this. I mean, one of the key findings has been that when we see air pollution improved, we also see reductions in the health effects, and we've demonstrably improved health in communities where air pollution has improved. It was demonstrated with the Southern California studies that when children moved out of the high air pollution levels, you could see improvements in their lung function. So improving air quality leads to better health.

CURWOOD: Arden?

Arden Pope (left) and Doug Dockery (right) at a Harvard symposium in October 2022 to honor Doug, a former chair of the Department of Environmental Health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The two pioneering researchers have spent four decades bringing the health effects of air pollution to the forefront of public health. (Photo: Steve Gilbert, Studioflex Productions.)

POPE: I think we should think of this as basically not just scientific discovery, but also to some degree, good news. Anytime you can find a controllable risk factor for disease and death, that is great news, because then what you can do is you can control that risk factor, and we could substantially improve the health and welfare of people throughout the world by finding ways to reduce our air pollution. And I actually don't think that that's an unreasonable expectation. So I think we should look at this as not just sort of, ah, the sky is falling, kind of research, but it's research that can be used to improve the health and welfare of populations everywhere.

CURWOOD: Arden Pope is a distinguished professor of economics at Brigham Young University. Doug Dockery is an emeritus professor of environmental epidemiology at the T.H. Chan Harvard School of Public Health. Thank you both for taking the time with us today.

POPE: Thank you, Steve.

DOCKERY: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: And their book is called Particles of Truth: A Story of Discovery, Controversy and The Fight for Healthy Air.

Related links:

- Read the 1993 Harvard Six Cities Study in the New England Journal of Medicine

- Read Dr. Arden Pope’s study on the Utah Valley Geneva Steel Mill

- Purchase Particles of Truth: A Story of Discovery, Controversy, and the Fight for Healthy Air from Bookshop.org to support Living on Earth and independent book shops

[MUSIC: Aves, “Smile” on Candle Lights, Artlist Original]

DOERING: If you enjoy the stories you hear on Living on Earth, please consider signing up for our newsletter. You’ll never miss a show, and you’ll have special access to show highlights, notes from our staff, and advanced information about upcoming live virtual events. The Living on Earth newsletter is sent to your inbox weekly. Don't miss out! Subscribe at the Living on Earth website, loe.org, that's loe.org.

[MUSIC: Aves, “Smile” on Candle Lights, Artlist Original]

DOERING: Just ahead, gather ‘round as our crew shares some Thanksgiving feast favorites. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Aves, “Smile” on Candle Lights, Artlist Original]

Thanksgiving Feast Favorites

The Living on Earth cast and crew shares their family recipes for Thanksgiving dinner. (Photo: Karolina Grabowska, Pexels, CC)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Roy Hargrove, Christian McBride, “Frosty The Snowman” on Jazz For Joy: A Verve Christmas Album, The Verve Music Group]

CURWOOD: Thanksgiving marks the beginning of the holiday season. So, families and friends are gathering around the feast to share staples as well as some less common traditions. And a couple years back we gathered some of the Living on Earth folks together to get a taste of those recipes.

DOERING: And because this is an encore, longtime listeners will hear a familiar voice you haven’t heard in a while. Our Beyond the Headlines contributor Peter Dykstra passed away in 2024, and we still miss him. But we’re grateful for the moments we shared with him over the years.

CURWOOD: So, sit back, relax and enjoy this mouthwatering starter course from producer Aynsley O’Neill.

O'NEILL: Yeah, I wanted to share my mother's pumpkin soup recipe, by way of Martha Stewart. You just cut up you know, two to three cups of pumpkin, simmer it with onion, garlic, salt, pepper, thyme, in either chicken or veggie broth. When that's all nice and tender, you puree the mixture, you got to be careful there because it's really hot, so be gentle with it. You return the pureed soup to the pot, and then you add some heavy whipping cream. Warm it first, so it doesn't curdle, and you serve it. And the Martha Stewart version suggests using a little mini pumpkin to serve it in.

Pumpkin soup makes a perfect starter course for Thanksgiving dinner. (Photo: Cala, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

PANDELIDIS: Aww!

O'NEILL: But we use mugs so that the family can walk around and mix and mingle before we sit down to the main course.

DOERING: How cute.

CURWOOD: And if anyone's listening to us wondering that they didn't scribble down this recipe fast enough. It can all be found on the Living on Earth website, loe.org. So hey, what's next, Jenni?

DOERING: Well, I think we've got Naomi Arenberg here and she picks the music every week. So Naomi, you've got some cranberries for us?

ARENBERG: I've got the reminiscence. I'm from a cranberry growing family. Both my father and grandfather were cranberry growers. And so that's the special part of Thanksgiving for me. You can use them, I think, in almost anything. I've got pie in front of me. And of course there's the sauce. I make it pure with just cranberries. You don't need to add water in the pot, but you can. A splash of home squeezed orange juice, a little bit of sugar. Always cut back on the sugar than any recipe has. Because you can always add it, but you can't take it out. And so just simmer that away until the cranberries are all popping in the pan. And be sure to let it cool thoroughly and sit for a day or more. And people will rave about your cranberry sauce. And I think that adds a bright, nice color to the table, whether it's Thanksgiving or any other holiday.

Music Coordinator Naomi Arenberg suggests adding fresh squeezed orange juice to make the perfect cranberry sauce. (Photo: Emily Carlin, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Yeah. Oh, man that, that cranberry sauce when it's bubbling away and making those popping sounds. It smells incredible too.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that's great. And I do a version of that: cranberries, just a little bit of water in the cranberries, and maple syrup where I am in New Hampshire, instead of conventional sugar and it tastes delicious.

DOERING: And you tap those trees yourself. Right, Steve?

CURWOOD: Well, we have historically. My mom has. I haven't recently been tapping them, but our neighbors do and it is delicious. Also, just when it comes to the stuffing, I also put cranberries in the stuffing that I make. I have to confess that not everybody likes that in my family. So I make two versions of stuffing: with the cranberries and then those without.

DOERING: So speaking of stuffing, I think our Technical Director Jacob Rego who is usually not heard, but he does all the work behind the scenes on this broadcast and podcast. I think he wanted to tell us about stuffing as well. What you got Jake?

REGO: Yeah, a recipe my family enjoys every year is Portuguese stuffing. It's a secret family recipe. But its key ingredient is a Portuguese sausage called chouriço. We never seem to have any leftovers, though, because it's a family favorite.

O'NEILL: Ooh, tasty.

CURWOOD: Mm, mm! That's so good. I've had food from where your family's from around New Bedford, Massachusetts. They put chouriço in almost everything and it makes it delicious. All right, let's turn now to our Director of Advancement and Program Strategy, Mark Kausch, who's famous for playing the double bass in symphony orchestras, but you have something else that's double for us today, Mark, I think?

Twice-baked potatoes can hold any toppings you like. Mark Kausch, the Living on Earth Director of Advancement and Program Strategy, enjoys his with scallions and bacon. (Photo: Jo Ziimny Photos, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

KAUSCH: Yes, double in a manner of speaking. Correct. At the front end of the pandemic, I reached out to my dad to say, hey, we're going to be trapped here in Minnesota, just the two of us, my wife and I. Can we have your twice baked potato recipe? He said sure. And it actually was one that he'd made up himself. It wasn't something that he found in a recipe book. And the more we got talking about it, the more it dawned on me that basically twice baked potatoes are kind of like making pizza or making nachos. You can kind of do whatever you want. Bake the potatoes, carve out the potatoes. Keep the potato skins as your bowls for later on. And then his recipe mashes in a bunch of butter, some scallions, bacon bits, with apologies to the vegans and vegetarians out there. But those are optional. And then you put it all back into the potato skins, and bake it for another 15-20 minutes. And I thought, well, this doesn't sound so hard, I can totally do this. And I was absolutely stunned at how complicated it turned out to be. And sadly, how I just couldn't quite do quite as well as dad did with his every-year recipe. I'm off the hook now because he's back at it. And I'm looking forward to his version and hoping that someday I'll do as well as he does. So, yeah.

O'NEILL: You'll have to shadow him in the kitchen this time around.

KAUSCH: There we go. Good thought.

PANDELIDIS: Dad knows best!

CURWOOD: Yeah, sounds like twice baked potatoes will be enough for a whole meal. Really, that could be the main entree.

KAUSCH: Yeah, I think you're absolutely right, Steve. And it's, it's always fascinating to me how more often than not, it's the side dishes that are the most fun at Thanksgiving, for sure.

DOERING: And some of the most filling. Well, I hope you still have some room in your stomachs because our Living on Earth contributor who looks beyond the headlines for us each week is here too. Peter Dykstra, what are you salivating over this Thanksgiving?

The late Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra also used bacon to top his Thanksgiving mac and cheese. (Photo: Daremoshiranai, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, I'm not salivating. I'm still chewing on all of the prior recipes that we've heard. But I come from a long line of meat-eating, environmentally-hypocritical relatives. My contribution usually is just good old mac and cheese. But with bacon in it. It's simple elbow mac. I tried it one year with gluten-free elbow mac, not realizing that gluten-free elbow macaroni turns basically into mashed potatoes when you try and use it. Cheddar cheese, because you don't want the four-cheese stuff. Because cheddar cheese will out-taste just about anything. And we top it off with a lot of crumbled bacon. And it's usually the first thing to disappear at our table full of carnivores, with occasionally environmentally-bankrupt and hypocritical means at the dinner table.

CURWOOD: Ha, okay. Hey, Jenni, what about you?

DOERING: All right, well, I hope you still have room because I love green bean casserole. And I have to say I used to hate the stuff that came from the can. You know, for me, it was these green beans that were cooked until death. So they were like gray, and then that can of mushroom soup from a can.

Jenni Doering makes her green bean casserole from scratch, following the Alton Brown recipe. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

PANDELIDIS: Ugh.

DOERING: But now I'm completely obsessed with making it from scratch. And Alton Brown has an amazing recipe where in a big cast iron pan, you put all this stuff together and you first do blanched green beans. Then you sauté mushrooms into a luscious and delicious roux. And then you top that all with crispy, thin sliced onions and it is just delicious.

CURWOOD: How does it sound to you Peter?

DYKSTRA: It sounds like something I can't eat, with all due respect. I'm allergic to all manner of beans. Green beans, pinto beans, lima beans, string beans. So if we eat any of those things in a restaurant, I'll have to order myself an ambulance.

CURWOOD: Oh my goodness.

DOERING: Oh, dear. Well, Steve, we're hearing some to-die-for Thanksgiving recipes from the Living on Earth crew. But we haven't even gotten to the turkey yet.

CURWOOD: All right. You know, only the strictest vegans and vegetarians omit the turkey at Thanksgiving. It's that one time of year where maybe people make the exception. And a succulent delicious turkey with rice stuffing is amazing. And I learned from my mother-in-law that you can cook a turkey at a very low temperature, just a little over 200 degrees, overnight to keep it really juicy and not have the top of it dry out. And of course then you put in that stuffing with the cranberries and it's, it's amazing. As a youngster where we live in New Hampshire, the neighbor would grow turkeys. And so we would go by, select the live turkey that we wanted and then it would show up in our kitchen, all fully dressed. And that took me a little while as a kid to make the connection. And when I did I was kind of sad, but you know if you're gonna eat meat, you got to take responsibility for the process. Okay, well what do you say Jenni? You ready for dessert?

An easy and tasty way to recycle your pie crust scraps is to brush them with melted butter, cinnamon sugar, and roll them up before baking. (Photo: Jessica Langlois, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: I'm ready. I mean, I might be bursting after dessert, but let's try.

CURWOOD: Okay.

DOERING: Kicking us off with dessert. I think we've got El Wilson. What have you got, El?

WILSON: Yeah, in my family we use the leftover pie crust to make cinnamon scraps. All you do is roll the crust into a sheet, cover it with melted butter. And then sprinkle it with cinnamon and sugar. You roll it up, cut it into pieces, and throw in the oven. They come out looking like mini cinnamon rolls.

O'NEILL: Mmm!

CURWOOD: Oh, yeah, that sounds really tasty. I'll have to try that. Now, Sophia Pandelidis, another one of our producers, I think you have a related dessert in your family repertoire, n'est-ce pas?

Sophia Pandelidis’ family takes their pie crust scraps and turns them into decorative pie toppers. (Photo: Courtesy of Sophia Pandelidis)

PANDELIDIS: Yeah, that's funny, El. My family does almost the same thing. We roll out the leftover pie dough and sprinkle it with cinnamon sugar, too. But then instead of making it into cinnamon rolls, we actually cut it out in fun shapes, like cookies, we're talking leaves or pumpkins. And then we use those little shapes to decorate our pies. So it's fun and tasty.

WILSON: Cute!

O'NEILL: I love that.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that gets to play with the nice thing about this feast part of the holiday, getting together with folks, is being together, cooking and making things. It's not just a meal. It's a gathering.

PANDELIDIS: Yeah. And it's an artistic process too.

DOERING: All right, so we've got all this leftover pie crust. What are some of our favorite pies to make out of that pie crust?

ARENBERG: Hmm. Don't get my mouth watering, please. I'll drip on the microphone. For me growing up as the daughter and granddaughter of cranberry growers, you can make a delicious, open-faced pie, please because it glistens. Even the next day. When you first take it out of the oven, invite everyone to circle around and look at this glistening creation. And then the next day, the color settles down. It stays really shiny. It's almost a stained-glass window there.

An open-faced cranberry pie. (Photo: Jennifer Pallian, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

O'NEILL: Ooh, beautiful.

DOERING: Wow.

ARENBERG: Yeah, too pretty to eat? Nah.

DOERING: Maybe a la mode, perhaps? Bit of vanilla ice cream?

ARENBERG: Yes, absolutely.

DOERING: It's my favorite way to eat apple pie.

CURWOOD: Any kind of pie! Well, thank you, Naomi. And by the way, speaking of pie, I should mention my grandmother's pumpkin pie, which was part of a very frugal Depression era way of thinking. If there are going to be pumpkins for decorating, they then need to be recycled into the pies that are going to happen at the holiday season. And grandma had a nice garden. Probably it was a victory garden for World War II at our house, and she grew her own pumpkins. But I guess not all pumpkins are made equal for this sort of thing.

Sugar pumpkins are ideal for making pumpkin pie. (Photo: Diliara Garifullina, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

ARENBERG: Correct. There is one variety that you often can find just in a normal, run-of-the-mill grocery store called sugar pumpkins that are grown to be used in a pie or in cooking.

CURWOOD: Probably explains why later in life when I tried to make pumpkin pie with ordinary pumpkins, they were kind of stringy and watery. Of course, you add enough sugar, you've got a pie. But now I know what grandma's secret was.

DOERING: So I think we're just about wrapped up here. But we have one more sweet thing to finish this out. Jacob, I think you've got something to offer.

REGO: Yeah, dessert that is required for our family's Thanksgiving is a homemade chocolate fudge. You can find the recipe on the back of a jar of marshmallow fluff. It's a delicious mix of sugar, chocolate, fluff, butter, vanilla and walnuts.

ARENBERG: Mm, mm!

O'NEILL: Ooh. My family, we also always have a chocolate course. Now we don't make it from scratch. But some chocolates, some clementines, some eggnog is the perfect way to wrap it up.

Our Technical Director Jacob Rego’s family loves making homemade fudge for Thanksgiving. (Photo: Rachel, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Ooh, and maybe a taste of rum for some people?

DOERING: Yeah, it depends what kind of eggnog you're drinking.

CURWOOD: Well, Jenni, I guess that's it. So we better get on with the cooking, right? Because this is not a quick meal to whip together.

DOERING: Yeah, I think this might take a few days to create everything. All this sounds like a recipe for a food coma for me at least.

CURWOOD: There you go. And if you've been listening to us, and you're thinking, "well, what about..." just go to our website and you can see all these recipes there. And if you have any luck, write to us about what works well in your kitchen.

ALL: Happy Thanksgiving!

CURWOOD: Happy Thanksgiving.

Related link:

Check out the Living on Earth Thanksgiving Recipe Book!

[MUSIC: Roy Hargrove, Christian McBride, “Frosty The Snowman” on Jazz For Joy: A Verve Christmas Album, The Verve Music Group]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Sophie Bokor, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jade Poli, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening and Happy Thanksgiving!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth