Air Pollution Pioneers

Air Date: Week of November 21, 2025

The Geneva Steel Mill in Utah Valley in 1989. The temporary closure of the mill on August 1, 1986 produced a natural experiment that allowed Dr. Arden Pope to show how air pollution doubled and at times tripled hospital admissions of children after the plant reopened on September 1, 1987. (Photo: Arden Pope)

We now know about the severe health impacts of tiny airborne particles or PM2.5, thanks in large part to the groundbreaking “Six Cities” study that started in the 1970s. The leaders of that team were Doug Dockery, who became chair of Environmental Health at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and Arden Pope, now a distinguished professor of agricultural economics at Brigham Young University. They are co-authors of the 2025 book, Particles of Truth: A Story of Discovery, Controversy, and the Fight for Healthy Air, and they share with Host Steve Curwood the story of how they undertook their vital research and the industry pushback they received.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

When you take a breath, an invisible poison may be entering your lungs alongside the oxygen you need. Tiny particles from burning everything from fossil fuels to forests can get deep into your lungs and even your bloodstream, exposing you to toxics like heavy metals and sulfates. We now know about the dangers of these particles, also called PM 2.5, but we were mostly in the dark about the scale of the problem and just how deadly air pollution could be until the 1970s. That’s when a team of researchers began the Six Cities study, which ultimately brought air pollution to the forefront of public health. The leaders of that team were Doug Dockery, who became chair of Environmental Health at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and Arden Pope, now a distinguished professor of agricultural economics at Brigham Young University. These two pioneering researchers who documented the health effects of air pollution are co-authors of the 2025 book, Particles of Truth: A Story of Discovery, Controversy, and the Fight for Healthy Air. Welcome to Living on Earth, Arden and Doug!

POPE: Thank you. We're glad to be here.

DOCKERY: Great to see you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Now breakthrough research often begins with some serendipity. So Arden Pope, please tell us what you observed and researched that kind of started much of this.

POPE: Well, for me, it started back in the 1980s, late 1980s when a steel mill in our local valley shut down for 13 months and reopened. And this actually produced a very interesting natural experiment where we could look at the changes in air pollution when the mill shut down, and we could also look at changes in pediatric respiratory hospital admissions. And although I was not really doing air pollution research at the time, this was such an interesting and unique natural experiment that I took advantage of it. The results were really quite dramatic. The air pollution from the local steel mill did appear to contribute not only a lot of pollution, but contributed to respiratory illness in children, and so I published that work, it caused kind of a local stir, as well as a generated interest by other researchers that were doing air pollution research, including Doug, and that just sort of led to ongoing efforts to further understand air pollution and its impact on health, and it's, it ended up being a career I never really planned, but it's been a good career.

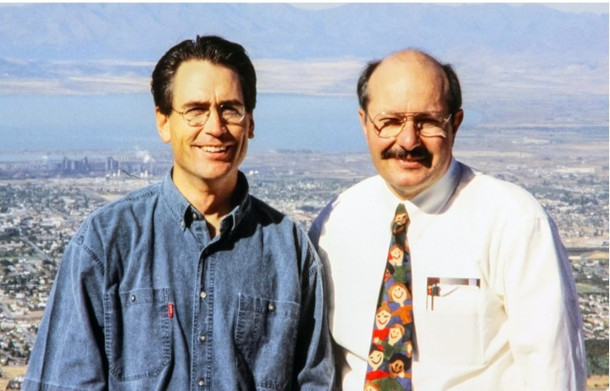

Dr. Arden Pope (left) and Dr. Doug Dockery (right) circa 1995, with Utah Valley and the Geneva Steel Mill in the background. Dr. Pope’s paper on the health effects of air pollution from the mill caught Dr. Dockery’s attention, leading to nearly four decades of collaboration. (Photo: Doug Dockery and Arden Pope)

CURWOOD: What were the health effects that seemed to have affected children?

POPE: The initial health effects that we observed were, were fairly straightforward. It was hospital admissions for respiratory disease in children, but follow up studies, some of them that I did with Doug and his colleagues at Harvard, found that the air pollution contributed to respiratory symptoms, reduced lung function, and then ultimately, as we started studying this more, we could see changes in mortality counts across time, both for respiratory disease and cardiovascular disease. So it was really quite striking.

CURWOOD: And Doug Dockery, how did you get together with Arden Pope and begin what led you to study the health effects of air pollution?

DOCKERY: We had been conducting a study in six cities across the United States for more than a decade when Arden's paper came out, and examining the effects of air pollution on respiratory health of children and adults. And when Arden's paper appeared, I got a call from a reporter who asked me to comment on it, and I had went back and read the paper, and I was just astounded at what an elegant study design it was. We had always wanted to do the type of experimental study where, what happens if you turn off air pollution? Can you see the benefits of that? And in fact, here he had this natural experiment and showing that when you did dramatically decrease the air pollution levels, you could see respiratory benefits of that. So we got in touch with each other. After that, Arden came to me and said, you know, I'm just an economist, I really don't know what's going on here. I have no experience in doing this. I'm getting beaten up by the local press about this, and I really need some help. And so we sat down, and I invited him to come to Harvard to make a presentation about his results, and we sat down and designed some follow up studies to strengthen the evidence from the work that he was doing, and that led to him coming to Boston on a sabbatical, and led to a long term collaboration we've had over the past 40 years.

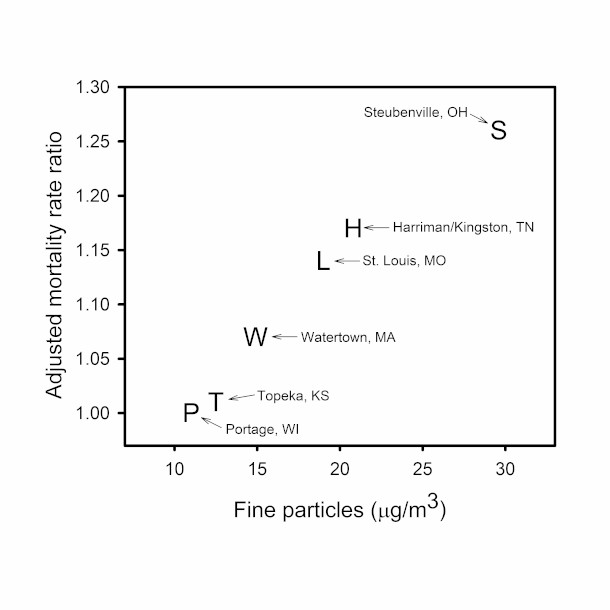

Estimated adjusted mortality rate ratios plotted over mean concentrations of PM2.5 from the original Harvard Six Cities study. The Harvard Six Cities Study published in 1993 in the New England Journal of Medicine revolutionized the field of environmental health, linking chronic exposure to fine particulate air pollution to increased mortality and shorter life expectancy. (Photo: Figure 4.1 in Particles of Truth. Adapted and replotted from results reported in Dockery et al. An Association between Air Pollution and Mortality in Six U.S. Cities, NEJM 329, no. 24 (1993): 1753-1759.)

CURWOOD: Harvard environmental health professor Douglas Dockery recalls that after meeting Brigham Young statistician and professor C. Arden Pope and learning of his work they set on a path of discovery which would lead to one of the biggest breakthroughs in modern environmental health. And it started back in 1973 with the Arab oil embargo raising prices and cutting supplies. The US government decided America should reduce the risk of imported oil by looking more to the abundant source of domestic energy, coal. And with the burning of coal comes a lot of air pollution. So, the Harvard team, including John Spengler, a co-chair of the World Media Foundation, which produces Living in Earth, wrote and won a federal grant in 1974 to research the impact of dirty air on respiratory health. They chose six US cities to study: Portage Wisconsin and Topeka, Kansas with relatively clean air, Watertown Massachusetts and St Louis Missouri with moderate pollution, and Harriman/Kingston Tennessee and Steubenville Ohio, which were downwind of nearby coal-fired plants. All six of these cities were in white and mostly middle-income census tracts, avoiding possible confounding variables of diverse ethnicity and economic status. In 1989 Dockery and Pope first learned of each other’s work when they were interviewed by Science News reporter Janet Raloff. They then combined forces and Pope came for a sabbatical term at Harvard. That began years of deep analysis that revealed they had a large data set showing that health effects from air pollution went well beyond its respiratory risks. Again, followed by Brigham Young professor Arden Pope, here’s Harvard professor Douglas Dockery describing the evolution of the Six Cities study.

DOCKERY: And we were following adults and kids in these communities with yearly examinations of their lung function and respiratory symptoms with the expectation that we would be seeing changes in their respiratory health. And ultimately, we did see those changes, but in the early 1990s, there was also evidence that when air pollution went up, we could see increases in daily mortality. And this raised the question, well, could we also see those effects on long term changes in life expectancy. In the communities with higher air pollution, we did in fact see shorter life expectancy by several years, in a fashion that really was very linear and very associated with these fine particle levels, what we now call PM2.5. And these are very substantial effects, much bigger than we expected, all in communities that at that time, were meeting the current air pollution standards to protect the public health.

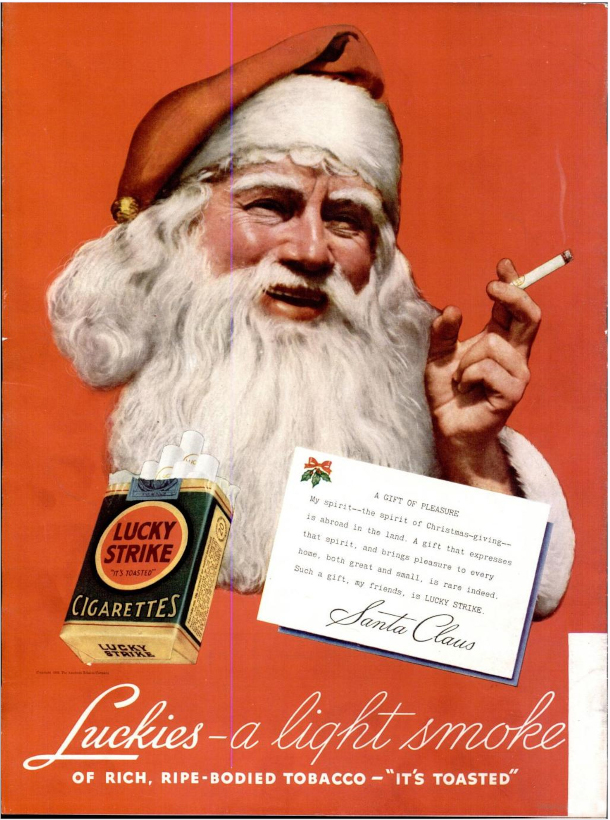

Lucky Strike cigarettes advertisement in Life magazine, 1936. The Harvard Six Cities study showed that on a population-wide basis air pollution in more polluted cities was contributing as much to attributable mortality as the fraction of people who smoked cigarettes. (Photo: Anton Rath, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: What kind of numbers were you talking about? What did you find in that first go around that surprised you? Arden?

POPE: I mean what we found is that in the most polluted city, there was about a 25 to 30% increase in mortality risk. Now that was stunning, because cigarette smokers at the time we knew that there was about 100% increase in mortality risk, but only about 25% smoked. But what we found is that there was about a 25% increase in mortality risk from just breathing. And of course, everybody breathes, and so the results implied that air pollution in the more polluted cities were contributing as much to attributable mortality as even cigarette smoking.

CURWOOD: Doug?

DOCKERY: We found that life expectancy was about two years shorter in the communities with higher air pollution. And put that in context, if you cured all cancers in the United States, the net effect on life expectancy in the population would be about two years. So we were talking about a identifiable risk factor here, air pollution, that was as big as all the effects of cancer, and that was very sobering to us at that time, especially considering that these were all communities that were meeting the air quality standards for public health at that time. I mean, we were stunned by this and knew we had to replicate these results. As Frank Speiser said at that time, this is not going to pass the laugh test if we put this out in a journal without validating this.

CURWOOD: And Arden Pope, your work shows a lot about the global burden of disease. Just how big a deal is this around the world, getting exposed to PM2.5?

Naples, Italy, in January 2025. The Global Burden of Disease Research Group estimates that fine particle air pollution contributes more to burden of disease than any other environmental risk factor and is in the top 10 of all risk factors contributing to disease and death globally. (Photo: keppet, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

POPE: So it's a big deal. In the United States we see these effects that Doug and I have been talking about, but the pollution in the United States is actually relatively low compared to exposures in many other parts of the world, China, India and other places. If you take the studies that we and others have done looking at the long term exposures to air pollution, and you use the results from those studies and apply it to exposures that people are exposed to around the world, you can estimate the global burden of disease, and this has been done by the Global Burden of Disease Research Group, and they estimate that fine particle air pollution contributes more to burden of disease than any other environmental risk factor, and is in the top 10, sometimes even in the top 5 of all risk factors contributing to disease and death. So it's a remarkably large impact. And I think Doug and I started working together nearly 40 years ago, and I don't think either one of us even imagined that air pollution was that large of a contributor to disease and death.

CURWOOD: Yeah, you have a chart in your book that says that this is more hazardous to global health than terrorism, car crashes, all kinds of things that we think of, infectious disease, kind of mind boggling, it feels like.

POPE: Yeah, I agree. I mean, it's been a big surprise to me that it has that large of an effect, and part of that's because these fine particles do have a lot of toxic materials, and they do contribute to both cardiovascular and respiratory as well as lung cancer. But the other thing is, is the exposure is so ubiquitous, pretty much everybody is exposed to this pollution, and in some parts of the world, the exposure is really remarkably high.

When the Harvard Six Cities Study was published in 1993, the Environmental Protection Agency was proposing a new standard for PM2.5, which would have required industry to reduce their emissions. (Photo: Texas GOP Vote, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Doug, the Harvard Six Cities study caused quite a backlash from various actors, particularly industry. In fact, I think you were accosted by protesters one time, and you went to Capitol Hill to testify about this. What happened?

DOCKERY: I had been invited to testify at a Senate hearing on air pollution, and in fact, had actually taken the train down from Boston and got off at Union Station. And then you walk up the hill to Capitol Hill to the Senate office building. And as I was coming up the hill, I encountered a group of people in white coats and funny glasses and holding signs with, "show us the data." And I was intrigued, and went up to see what they were about, and found they were actually demanding the data from the Harvard Six Cities study. And it was really the first episode I'd encountered where we were being challenged like this. And it turned out that this was a demonstration that had been organized by the Center for Sound Economy, which was funded by the Koch brothers, to protest our work. And it follows the example of demands that have been developing to undermine epidemiology studies by demanding release of potentially personal data from the participants in our study.

CURWOOD: They charge that you were conducting "secret science." What the heck is that? And why is such an allegation designed to make human health research impossible from your perspective, Doug?

Charles Koch in 2019. Charles G. Koch and his brother David H. Koch funded organizations like the Center for Sound Economy, which sought to discredit the Harvard Six Cities study. (Photo: Gavin Peters, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DOCKERY: Well, of course, when we approached people to be participants in our study, we said we would keep their information confidential. So various groups came forward and said, well, we can only believe these data if we get to analyze them ourselves. And so we certainly made a practice of making data available to other investigators to analyze or reanalyze the data, but not to the extent that it would be identifiable as individuals and potentially compromise the assurances of confidentiality that we had agreed to.

CURWOOD: So Arden, what's going on here? What do you think this charge of "secret science," and I gather you guys were hit with a bunch of subpoenas and from the Congress and such, what do you think they were trying to do here?

POPE: Well, it was very clear that there were these special interests that did not want to see these studies used to result in stronger regulations for air pollution, stronger standards for PM2.5. In fact, shortly after the Harvard Six Cities study and related studies were published in the mid 1990s, the EPA was proposing a new standard for PM2.5 that would require industry and other polluting sources to reduce their emissions. And so it's way easier to make a lot of money if you don't have to pay part of your costs. And part of the costs of burning fossil fuels are these health costs that we were observing, and so one way to try to avoid those costs is to simply deny them. And that seemed to be what was going on, and I think is still going on to some degree.

CURWOOD: And by the way, I think some of the folks who brought actions, even some litigation, states like West Virginia, for example, are still doing that when it comes to climate disruption.

POPE: Yeah, the sort of strategies to deny this research were developed actually to discredit some of the studies with regards to cigarette smoking. These strategies have been used to deny the effects of air pollution and also deny the effects of the greenhouse gasses and the impact on, on our climate.

CURWOOD: So obviously, Six Cities study is a big deal and comes under attack. How was it backed up by subsequent research?

The 2025 Palisades fire in Los Angeles. Our guest Dr. Doug Dockery warns that pollution from wildfires will continue to threaten public health. (Photo: Frank Kovalchek, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

POPE: When we got the results, at least the initial results from the Harvard Six Cities study, we were as surprised as anybody. We did not expect to see such large impacts of air pollution on respiratory and cardiovascular disease mortality. And so we actually contacted the American Cancer Society, collaborated with them to use another big, large cohort that they had been following so that we could see if we could replicate the results of the Harvard Six Cities study. And in fact, in general, we were able to replicate those results. And so we published the results of both of those studies back in the mid 1990s and then even both of those were criticized. And then we actually cooperated with the Health Effects Institute and a research team that did a big reanalysis of both of those studies to see if they could replicate the results, see how robust they were. And in fact, they replicated the results and found that they were remarkably robust. And then since that time, there have been many other cohorts that have been analyzed, the US, in Canada, in Europe, in China, and in general, they are finding basically similar results.

CURWOOD: So Doug, where are we in terms of improving air quality, both here in the United States and around the world? I think around the world, deaths from particulates are on the scale of like 7 million a year excess deaths. What extent have we made significant strides, and what can we do to bring those numbers down?

DOCKERY: Well, I think there is a positive story here in that when you compare air pollution now to where we were 40 years ago when we started this research, we've seen very, very substantial improvements in air quality across the United States, but we're still seeing effects, for example, of uncontrolled wildfires impacting large parts of the United States. Internationally, there's been recognition of where the high air pollution levels are, particularly with the use of satellite data, which provides information on areas where there was no monitoring before. And so we recognize now, in Africa, in Southeast Asia, in China, the very, very high concentrations that existed before there. But also this has brought pressure on the local governments to actually take some action. So we are seeing progress around the world as it's been recognized, that these are preventable health effects, and there is a real opportunity to have substantial benefits from this. I mean, one of the key findings has been that when we see air pollution improved, we also see reductions in the health effects, and we've demonstrably improved health in communities where air pollution has improved. It was demonstrated with the Southern California studies that when children moved out of the high air pollution levels, you could see improvements in their lung function. So improving air quality leads to better health.

CURWOOD: Arden?

Arden Pope (left) and Doug Dockery (right) at a Harvard symposium in October 2022 to honor Doug, a former chair of the Department of Environmental Health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The two pioneering researchers have spent four decades bringing the health effects of air pollution to the forefront of public health. (Photo: Steve Gilbert, Studioflex Productions.)

POPE: I think we should think of this as basically not just scientific discovery, but also to some degree, good news. Anytime you can find a controllable risk factor for disease and death, that is great news, because then what you can do is you can control that risk factor, and we could substantially improve the health and welfare of people throughout the world by finding ways to reduce our air pollution. And I actually don't think that that's an unreasonable expectation. So I think we should look at this as not just sort of, ah, the sky is falling, kind of research, but it's research that can be used to improve the health and welfare of populations everywhere.

CURWOOD: Arden Pope is a distinguished professor of economics at Brigham Young University. Doug Dockery is an emeritus professor of environmental epidemiology at the T.H. Chan Harvard School of Public Health. Thank you both for taking the time with us today.

POPE: Thank you, Steve.

DOCKERY: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: And their book is called Particles of Truth: A Story of Discovery, Controversy and The Fight for Healthy Air.

Links

Read the 1993 Harvard Six Cities Study in the New England Journal of Medicine

Read Dr. Arden Pope’s study on the Utah Valley Geneva Steel Mill

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth