October 3, 2025

Air Date: October 3, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Youth Climate Case

View the page for this story

A preliminary hearing recently took place in federal court for the youth climate case Lighthiser v. Trump, in which plaintiffs are seeking immediate relief from three executive orders and subsequent actions of the Trump administration that boost fossil fuels. But the federal government maintains that the Lighthiser plaintiffs, like those in the prior case Juliana v. United States, lack standing. Environmental law veteran Pat Parenteau speaks with Host Aynsley O’Neill about the challenging legal basis for this lawsuit. (14:16)

Salmon Run Fattens Bears

View the page for this story

The champion of Fat Bear Week 2025 is officially number 32 - “Chunk”, a big male who overcame a broken jaw to take the prize. Mike Fitz, the resident naturalist at explore.org, launched Fat Bear Week as a ranger at Katmai National Park in Alaska. He joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain how this year’s strong salmon run in the Brooks River helped the local grizzlies bulk up. (15:20)

BirdNote®: Black Swifts Reach for the Moon

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

There are all sorts of ways that life on Earth takes advantage of the regular cycles of the moon, from horseshoe crabs and grunion fish that lay their eggs during the high tides of a full moon to corals that spawn en masse in the days afterwards. Michael Stein reports for BirdNote® on how black swifts are also synced to lunar cycles and fly higher during the full moon. (02:33)

Encountering Dragonfly: Notes on the Practice of Re-Enchantment

View the page for this story

In lives full of screens and distraction, it can be hard to truly notice the natural world and the subtle ways that other creatures cross our paths. But author Brooke Williams believes these signs from nature can bring us important insights that are worth paying attention to. He sat down with Host Jenni Doering to chat about how he explores these ideas in his book, Encountering Dragonfly: Notes on the Practice of Re-Enchantment. (12:03)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

251003 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Mike Fitz, Eva Lighthiser, Pat Parenteau, Brooke Williams

REPORTERS: Michael Stein

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Young people suing the Trump administration over climate change face an uphill battle.

PARENTEAU: Their futures are at stake. They don't really have any choice but to fight and to insist that their concerns be not only taken into account but that, you know, the adults in charge of these programs and these governments do the right thing, do what they're supposed to do.

DOERING: Also, the quest to become “re-enchanted” with the natural world.

WILLIAMS: I think it was Einstein – at least he gets credit for saying, I’m not sure he really did – that either everything is a miracle, or nothing is a miracle. And, if you get to choose, which are you going to choose? Why not pick everything is a miracle and start to like live as if that’s the case?

DOERING: Plus Fat Bear Week and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Youth Climate Case

Eva Lighthiser is the lead plaintiff in Lighthiser v. Trump. She was previously involved in a different youth climate case, Held v. Montana. (Photo: Our Children’s Trust, Eillin Delapaz)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Around the world, as governments fall far behind on the ambition needed to address the climate emergency, young people are turning to the courts for help in ensuring they have a future to look forward to. And in 2023, Held v. Montana became the first climate lawsuit in U.S. history to go to trial and secure a legal victory. Represented by Our Children’s Trust, the plaintiffs were able to successfully argue that the “right to a clean and healthful environment” enshrined in the Montana constitution meant the state had to fully consider climate impacts when permitting new oil and gas operations. But the U.S. constitution has no such mention of a clean and healthful environment. And thus, a different landmark climate case, Juliana v. United States, never overcame procedural tangles, with lengthy arguments over whether the plaintiffs even had the standing to sue their federal government over its decades-long practice of promoting fossil fuel development. So the plaintiffs in the new lawsuit Lighthiser v. Trump are trying a different tack. We turn now to Pat Parenteau, with five decades of experience in environmental law. For full disclosure he has financially contributed to Our Children’s Trust in the past. He’s here to give us his perspective on their new climate case. Pat, welcome back to Living on Earth!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Aynsley, it's good to be with you.

O'NEILL: We just had two days of hearings out there in Montana. What happened during those two days? Who was giving this sort of testimony?

PARENTEAU: Yes, so our Children's Trust is representing, once again, a group of youth plaintiffs. I believe there's at least 22 of them. So the main focus of this two-day hearing before Judge Christensen in Montana Federal Court was the request of our Children's Trust for a preliminary injunction. Okay, so we're at the early stage of this lawsuit, and the idea of a preliminary injunction is to sort of hold everything in place until we can get to a trial on the merits. Meanwhile, the Trump administration is trying to throw the whole case out and not have any hearings at all. So that's kind of where we are at this point.

Youth plaintiffs outside the US District Court for Montana where the two-day hearing on Lighthiser v. Trump took place. Front row: Eva, Jasper, Nate, Jeff, Jorja, Miko, Delaney. Back row: Joseph, Isaiah, Charlotte, Georgi, Grace, Olivia, Taleah. (Photo: Our Children’s Trust, Eillin Delapaz)

O'NEILL: What are the three executive orders that were brought up in Lighthiser v. Trump, and what are the plaintiff's arguments against those?

PARENTEAU: So the three executive orders are number one “Unleashing American Energy,” which means prioritizing fossil fuel development over renewables. The second one is “National Energy Emergency,” which is basically triggering fast track procedures to build fossil fuel infrastructure. And the third is eevitalizing the coal industry by designating coal as a mineral on public lands, which opens up all kinds of fast track approval of leasing and oil and gas development. So those are the three executive orders. The attacks on these three orders are both constitutional. So the youth plaintiffs are saying, if you take all of these together and all the actions that are required to implement them, they are jeopardizing our life and our freedom under the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The other thing that the plaintiffs are arguing is that even if these orders aren't unconstitutional, they're illegal because they exceed the President's statutory authority. So those are the two primary arguments. One, the orders are unconstitutional. Two, they're illegal because they exceed the President's statutory authority.

O'NEILL: So after this first two days, what do we think is going to happen next? You know, we're so far away from a trial, Pat, so what do we have to do in between in order to even get close?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, so the idea of a preliminary injunction is to preserve what the courts call the status quo. In other words, stop everything while we get ready for trial. Judge Christensen expressed considerable doubt about his ability to do that, and he kept asking the plaintiffs lawyers, Julia Olson and others, what exactly are you asking me to do? And my concern as a judge is both, do I have the authority to do what you're asking, but also, as a practical matter, are you asking me to monitor everything the Trump administration is doing every day, because I can't do that. So, you know, I have to say it's very doubtful that Judge Christensen is going to order the kind of injunction that the plaintiffs would like to see him order.

O'NEILL: And Pat, to what extent is Judge Christensen able to say, "I can't let this full case move forward, but we need to whittle it down, let's choose one of these executive orders to focus on,” or something along those lines?

Supporters cheering on the plaintiffs in Lighthiser v. Trump as they walk into the courthouse during their hearing. (Photo: Our Children’s Trust, Eillin Delapaz)

PARENTEAU: Yeah, he may very well call the parties into an open public hearing and sometimes they do these things in camera, as they say in his chambers. I think he's probably going to try to narrow the case or at least convince the plaintiffs to narrow the case. If he denies an injunction, if he keeps the case alive, I'm saying, he may say I will entertain motions for injunctions aimed at specific actions. Let me give you an example. So the EPA just announced that sources of greenhouse gas emissions, industrial sources, no longer have to report their emissions. Now this has been a requirement of not only federal law, but international law. We were, I should say, parties to the Paris Agreement that requires reporting of greenhouse gasses and even the original, what's called a Framework Convention on Climate Change, all the way back to 1992 we are parties to that original framework treaty. In that treaty, we committed to reporting our greenhouse gas emissions to the world, to the US public, of course, but to the world more broadly. So here's the point, that's a really specific, discrete action that frankly, I think is illegal, telling the industry they don't have to report greenhouse gas emissions. So judge Christensen could say if you have something really specific like that and they're relying on one of these executive orders to do that, I would entertain a motion to stop that. I won't guarantee you I'll issue the order, but I would at least consider it. We may see something like that happen if he both denies the preliminary injunction but also denies the Trump administration's motion to throw the whole case out.

O'NEILL: And what do we know about how judge Christensen has treated maybe similar climate related cases in the past?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, he's a very reliable judge when it comes to environmental cases generally. In other words, he understands the threats to the environment and he will very much understand the threats from climate change. I don't think he's gonna, he's not, he's not a climate denier. He's not an ideologue at all. He's a very good judge, but he's also a judge, a district court judge that has to pay attention to what's happening above him, specifically the US Supreme Court. And we know from other conversations we've had that we do not have a sympathetic Supreme Court when it comes to environmental regulation, far from it. We have a court that seems to be outright hostile to federal regulation of climate related matters. So Judge Christensen is a smart enough judge to know he can't just do what maybe his instincts tell him he would like to do. He's got to do something that won't get overturned on appeal, that won't accomplish anything, and he's also got to be careful that he's within the bounds of what a federal district judge is actually authorized constitutionally to do. Judges don't set policy, people think they do, but they don't. They try to adhere to their job of applying the law to the facts of a case, a controversy before them, and issuing remedies that they have the power to enforce. And that's where things get tricky with a case like this, is can he actually enforce whatever order he issues? We've seen already, the Trump administration doesn't always respect the orders they're given from federal courts, certainly not from judges, they disagree with judges they think who are too liberal, for example. So judge Christensen has to think all the way through to the point of, if I issue this order and the government doesn't comply, then what do I do? Am I faced with having to hold the President or his officers in contempt, in criminal contempt perhaps. See, it gets more and more difficult the further you go with this.

O'NEILL: So Pat This is you know, yet another of these youth led plaintiff cases. What does that say to you about the morale and the center of the US environmental movement right now?

Pictured above is a gas flare from the Bayport Industrial District in Harris County, Texas, an area with a concentration of petrochemical companies. As part of a series of executive orders, the Trump administration declared a national energy emergency, supporting the domestic production of fossil fuels. (Photo: Jim Evans, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 4.0)

PARENTEAU: Well, it's certainly true that the youth movement that's represented by the Lighthiser case, and frankly, all of the cases being brought by our Children's Trust, that the youth are not going to be discouraged or dissuaded, regardless of what happens at this particular juncture. You know, in the Lighthiser case. They're determined to push and demand really reform. Their futures are at stake. They don't really have any choice but to fight and to insist that their concerns be not only taken into account, but that, you know, the adults in charge of these programs and these governments do the right thing, do what they're supposed to do. And it really is all over the world. You know, we just saw the International Court of Justice, for example, issue a landmark, it's an advisory opinion, but it's an incredible legal document that finds that, yes, indeed, the nations of the world have an obligation to not only the youth of the world. It was brought by youth plaintiffs. The effort to get the International Court of Justice to take the case was pushed by young people. So that's an example of where in the larger context, young people all over the world are going to court, going to international tribunals, insisting that the threats to their future be taken seriously and that actions to correct that be taken now, when there's still time to do so, and they're bringing to bear not only just arguments, but facts and expert testimony. In the Lighthiser case, they had six expert witnesses across the board, economists, engineers. So the point is that I do see the energy coming from the young people bringing these cases.

O'NEILL: Pat Parenteau is an emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School. Pat as always, thank you so much for joining me today.

PARENTEAU: Well, thanks for having me on the program Aynsley, I appreciate it.

DOERING: You know, Aynsley, this case does face an uphill battle but as Pat said the youth are determined to try. And lead plaintiff Eva Lighthiser shared a few thoughts with us on what’s really motivating her to be a part of this tough fight.

LIGHTHISER: Growing up and seeing the effects of climate change firsthand has been really frightening to see. And I have had a lot of climate anxiety and worry about where we’re going. And knowing that there was a way, a route for me to take action, that could make change, it made it kind of feel like a no-brainer to me.

O’NEILL: And Jenni, Eva was also a plaintiff in the Held v. Montana case that eventually won in the state supreme court, but she must have been pretty young when that started, right?

DOERING: Yeah, the Held case was filed in early 2020 and so Eva Lighthiser has really come of age during the years she’s been involved in these youth climate cases. Now she’s a freshman in college and she says this time in court feels different, and not just because it’s a federal case.

LIGHTHISER: I entered that courtroom with a lot more confidence and a lot more excitement, I think, than the first time I entered the courtroom during the Held v. Montana case, because I’m a whole lot less scared of speaking up and using my voice now, which is nice.

O’NEILL: Well, sounds like Eva and the other kids in this case may need all the confidence they can muster to see this through.

DOERING: What, going up against the federal government itself and the fossil fuel industry to boot? And with an unprecedented legal argument? Pssht, should be a piece of cake.

O’NEILL: Or you could say child’s play. Now, looking at this from the defense side, in its motion to dismiss the case, the government maintains that like the Juliana case that was ultimately dismissed by the US Supreme Court, the plaintiffs in Lighthiser also lack standing. The motion reads, quote:

“Plaintiffs’ most recent complaint suffers from the same jurisdictional defects as those of Juliana. A self-designated group of children and young Plaintiffs claim they are better positioned to set national energy policy than the President of the United States. Those grievances are for the political branches, not the courts. Plaintiffs maintain they are injured by climate change, but they fail to show how their requested declaratory and equitable relief will redress those injuries. And in challenging dozens of discrete (and non-final) agency actions in one omnibus complaint, Plaintiffs transparently attempt to circumvent statutory judicial review provisions under the Administrative Procedure Act, the Clean Air Act, and numerous other statutes. The Court should again reject these efforts to forge a judicially constructed end-run around the democratic process and statutory review schemes.” End quote. And you can view Lighthiser v. Trump case filings from both parties on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Read the Government’s Brief of the Motion to Dismiss

- Read the brief in support of motion for preliminary injunction filed by Our Children’s Trust

- Montana Free Press | “Youth Plaintiffs Challenging Trump Energy Orders ‘Optimistic’ After Days in Court”

- Learn more about Pat Parenteau

- Learn more about Lighthiser v. Trump from Our Children’s Trust

- Watch A Verdict for the Planet: Legal and Political Reflections on the ICJ Climate Ruling

[MUSIC: Candelion, “Betula” Single, Epidemic Sound]

DOERING: Coming up, the chunky champion of this year’s Fat Bear Week overcame a broken jaw to take the prize.

FITZ: Chunk is a big bear, like a 1200 pounder, at least. He’s probably fatter than that but we don’t know for sure; but at least 1200 pounds. He's one of the more dominant bears at the river, he's been the river's most dominant bear.

DOERING: That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Candelion, “Nylon String Theory” Single, Epidemic Sound]

Salmon Run Fattens Bears

Every year, the brown bears in Katmai National Park and Preserve are viewable on live webcams via explore.org. In early fall, dedicated fans vote for their favorites to win the annual Fat Bear Week bracket competition. (Graphic: Courtesy of explore.org)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Every year, Katmai National Park and Preserve in southwest Alaska hosts perhaps the fiercest bracket competition the animal world has ever seen. Fat Bear Week showcases the park’s famous brown bears, who have spent all summer feasting on fish to get ready for winter hibernation. Voters from around the world champion their favorites, sometimes on size alone, but also on the individual stories that you can follow by watching the online webcam footage. Mike Fitz is the creator of Fat Bear Week, which he started when he was a park ranger at Katmai National Park. He now works as the resident naturalist for explore.org, which hosts Fat Bear Week. He’s also written a book on these corpulent creatures, The Bears of Brooks Falls: Wildlife and Survival on Alaska’s Brooks River. And now he’s on the line. Mike, welcome to Living on Earth!

FITZ: Happy to be here, and Happy Fat Bear Week.

O'NEILL: Happy Fat Bear Week! So, the world has been celebrating Fat Bear Week now for over a decade. Tell us, how did you first come up with the idea for a contest like this back in 2014?

FITZ: Well, bears need to get fat to survive, right? Fat is the fuel that powers their ability to survive winter hibernation. And when I was a ranger at Katmai, we would see many of the same bears in early summer and in late summer, and we would see their body mass changes. So that was one of the things that we always talked about with the park visitors. But in late September 2014, I was browsing webcam comments on explore.org, and I saw a pair of screen captures from the webcams of the same bear from an early summer photo and a late summer photo, and the person remarked, hey, look how fat this bear got. Something in my brain clicked at that moment, and I thought, wouldn't it be fun if we allowed the webcam audience to decide who was the fattest and most successful Brooks River bear of the year? So we came up with this idea for a thing called Fat Bear Tuesday. It was a one-day tournament. We put it on Katmai's Facebook page, people voted with their reactions or likes, and that day, I decided, this needs to be expanded into a whole week to give more people the opportunity to participate. And that's how the idea for Fat Bear Week was born.

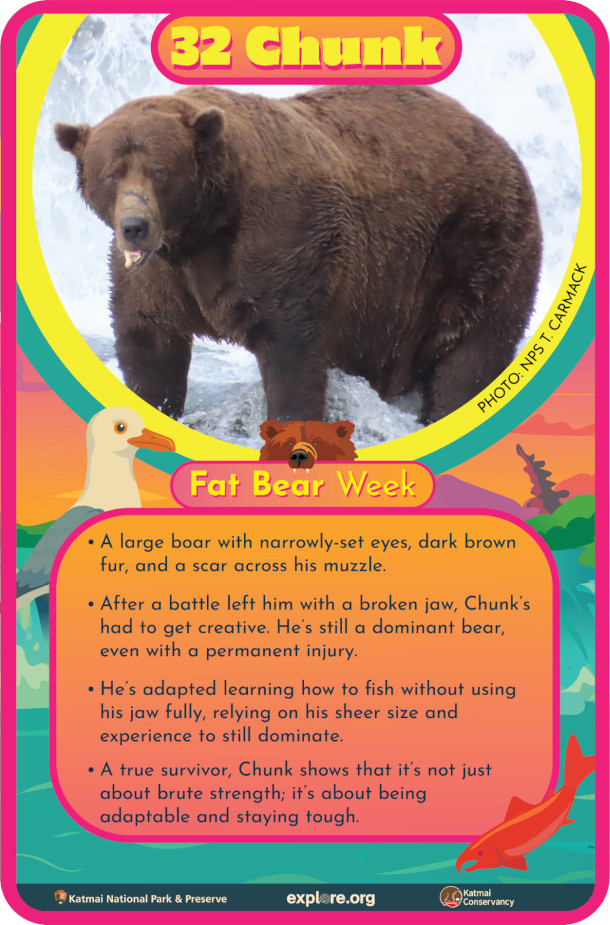

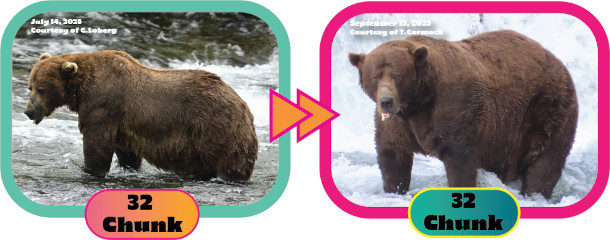

O'NEILL: I love it. I love just a full bracket, and you just get to look at all these great photos and well, congratulations to this year's winner of Fat Bear Week, 32 Chunk. What can you tell us about 32?

FITZ: He's one of the largest bears at Brooks River, and has been so for a number of years. So Chunk is a big bear, like a 1200 pounder at least. He's probably fatter than that, but we don't know for sure, but at least 1200 pounds. He's one of the more dominant bears at the river. He's been the river's most dominant bear, like last year in 2024 he was. This year, however, he had a pretty severe setback in June when he broke his jaw. We don't know how he broke his jaw, but the timing of it and the nature of the injury strongly suggest he broke it in a fight with another bear. So he's had to deal with the pain, the suffering, but Chunk is powering through it, and he's done so throughout the year. He's gotten really, really fat, and he's done remarkably well for himself this year. So I think with his, his resilience, his perseverance, I think that story resonated with a lot of Fat Bear Week voters. And Chunk has been like the runner up, I think, the past two years in 2023 and 2024, so this seemed like it was his year.

Before and after photos of 32 Chunk, this year’s Fat Bear Week bracket champion. 32 Chunk had been runner up in years past. (Graphic: Courtesy of explore.org)

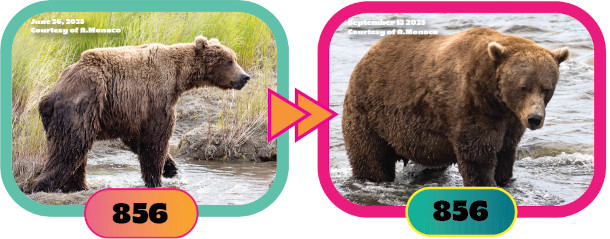

O'NEILL: And Mike, tell us about our runner up here.

FITZ: 856, his story resonated with people because he's an older adult male, so he can't compete like he had in the past, and he was the river's formerly most dominant bear. I mean, he became hyper dominant, like in 2011 and just like was at the top, the very tippy top of the bear hierarchy at the river, and he held that position for more than a decade.

O'NEILL: Now, Mike, I'm curious why some of these bears, like Chunk, get names and others are just known by sort of these numbers.

FITZ: There's no official nicknaming process with the national park staff at Katmai. So some of the bears just kind of get nicknames over time informally. Chunk actually got his nickname just as a memory aid for the biologists who were identifying bears. So he was just on his own for the first time in 2007 as a two and a half year old, and he was pudgy then, and he's kind of grown into that nickname since that time. 856 has never had a nickname, and I can't actually imagine calling him anything else than 8-5-6 or 856, he's just always going to be that number for me.

O'NEILL: And so in order for these bears to get so big, what exactly are they eating?

FITZ: Brown bears are omnivores, just like people, so they eat a wide variety of foods, but in Katmai National Park, salmon are especially important to brown bears, so they have a higher percentage of meat and protein in their diet compared to a lot of brown and grizzly bears throughout North America. And that's one reason why they can grow so large is because they have access to ample runs and large runs of salmon. And salmon are such a great food for bears because they're not only high protein, but they're also very high fat as well.

O'NEILL: Mmhmm. And so, on a daily basis, how much salmon do these bears tend to eat?

856 was this year’s Fat Bear Week bracket runner-up. Though he’s never won the competition, 856 had been the dominant bear in the Brooks River for a number of years. (Graphic: Courtesy of explore.org)

FITZ: Depends on the bear, depends on the day it's having, depends on the amount of fish that are moving through the river that day. But on a good day, a bear can easily catch 20 to 30 salmon. So yeah, they'll eat a lot of salmon. I think the record that I saw personally was a bear that ate like 42 salmon in about five hours. These aren't small fish either. I mean, a sockeye salmon can average about five pounds in Brooks River.

O'NEILL: In order to support that volume, it sounds like the salmon run must do, you know, pretty well each year. How was it this year?

FITZ: This year's salmon run in Brooks River was exceptional. It was so great. I mean, we saw wall to wall salmon, like from early July until like, the middle of August, and hundreds of salmon jumping the waterfall every minute. So it was really incredible to watch. And Bristol Bay, the Katmai region, is home to the last great salmon run left on earth. One of the things that was special about Brooks River this year, though, and the salmon run, was that there were so many fish in the river that the bears were essentially released from food competition. In a normal year where there are fewer salmon, or maybe just waves of salmon moving into the river, bears will go to Brooks Falls, and they'll compete for the most productive fishing spots. We didn't really see that in early summer this year, because there was no single good fishing spot. Fishing was good everywhere along the river, we saw bears expressing a lot more tolerance, a lot more playful activity between bears. And to me, that was another demonstration of their behavioral flexibility, their behavioral plasticity. They are adaptable creatures. They're very smart animals, very sentient and aware of their environment and the circumstances that they adapted to this summer, I think, was just another great example of that.

O'NEILL: And by the way, the parts of the salmon that these bears discard, what happens to those?

FITZ: There's no waste in nature. So those parts of, the discarded parts of the salmon are cleaned up by scavengers. Maybe that's a hungrier bear downstream. Maybe that's a bald eagle, maybe it's a gull. Could be, you know, another animal or a decomposer, especially. One of the more fascinating aspects of this dynamic as well is that plants grow faster in areas where salmon are coming back into these watersheds. So bears, they are maybe carrying salmon carcasses into the forest or the marshes along a river, for instance, they're also carrying salmon nutrients through their digestive system, so they will leave deposits in their scat out in the forest, or they'll urinate in the forest. And that helps to boost the productivity of plant life around these watersheds as well. So salmon are really kind of like the gift that keeps giving.

O'NEILL: So we're talking to you right now at the beginning of fall. What are these bears going to be doing now? Walk us through the beginning of fall to next summer.

FITZ: So they're storing up basically a winner's worth of food to survive that period of time where they have no access to food. So yeah, right now they're going to be concentrating more and more on eating. Over the next several weeks though, their metabolism is starting to ramp down. It's a really kind of slow transition down into their hibernation mode. Their appetite will decline. They'll eventually wander off to their dens. They will build and construct their dens on steep slopes that collect and hold a lot of snow. In Katmai, they're basically just digging a den straight into the earth, straight into a hillside, and then they'll eventually go in there, and they'll begin hibernating, generally in November for most bears in Katmai, although it ranges from maybe like late October into December, when they begin hibernation.

O'NEILL: And to what extent are you able to monitor them during their hibernation period? And I don't just mean you and the scientists who work with them, but what about the public? Are there any live cams that we'd be able to use to check up on our favorite bears? Or do we just have to wait until next year?

FITZ: Yeah, we're gonna have to wait until next year. In Katmai National Park, the locations of bear dens are too unpredictable for us to say, hey, let's put a cam in this location. But we've learned a lot from webcam observations of bears in dens in other places. And then also, sort of like the miniaturization of technology has allowed scientists elsewhere, like in Scandinavia, to actually implant like heart rate monitors and things like that on brown bears and radio and GPS collars, for instance, to know where they're denning, and then you can check and see you know what the heart rate monitors are telling us about brown bear physiology and metabolism inside of the den. So with brown bears in Katmai, we can kind of only extrapolate about what their hibernation experience is like, and that's based on observations from either like captive facilities or some more rarely, some wild observations in other parts of the world.

Fat Bear Week would not be possible without a healthy sockeye salmon run on the Brooks River. (Photo: Courtesy of Russ Taylor, Katmai National Park and Preserve)

O'NEILL: And right now, the world is facing a few ecological crises. I'm talking climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution. How are the bears faring with these issues on the rise?

FITZ: In Katmai National Park, they're doing really well, and that's largely because the ecosystem there is intact, right? Katmai is a very remote National Park. It's almost exclusively undeveloped. There's hardly any trails. You have to fly or take a boat to get there. So the watersheds are healthy. They're unengineered. The salmon runs right now are ample, but that doesn't mean that they're not facing threats due to climate change, for instance. The hydrology of the park is certainly changing. Glaciers are melting. Ice cover along the volcanoes has declined significantly over the last century. We know that the lakes and rivers are getting warmer. We know that the oceans are getting more acidic as they absorb CO2 from the atmosphere. All of those things have this significant potential to disrupt the sockeye salmon run in Bristol Bay. So they're doing well in some respects, but also, you know, the future does, does pose some significant challenges for them.

O'NEILL: Well, it's good to hear that these bears are doing pretty well, all things considered. But for fans who pay attention, maybe just during Fat Bear Week here in September, what can they do the rest of the year to show some support or appreciation for these bears?

FITZ: I think there are several things that people can do. One of the things that we can do is just share, sort of like the, the story of Katmai and Bristol Bay and the Brooks River bears and the Fat Bear Week bears with other people. And that's really special, right? You know, with the biodiversity loss and the extinction crisis happening around the world, often we get overwhelmed with these doom and gloom stories, but there's a lot to celebrate. There's a lot to save out there. And I think we can look at sort of like Bristol Bay, and we can look at Katmai as one of those examples of things that we can work towards in other places as well.

O'NEILL: And Mike, in addition to being the, you know, creator of Fat Bear Week and an author, you currently work as a naturalist with something called explore.org. Tell us a little bit about your role there, please.

FITZ: Yes, I'm the resident naturalist with explore.org, and we are a philanthropic organization that specializes in live nature cams of animals in nature. I think we have something like, currently, 190 live cams around the world, so there's always something to watch. For example, like in the morning, maybe before the brown bear cams in Katmai go online, I might go to Africa, for instance. I was actually watching hummingbirds at a feeder in southern Arizona this morning before we talked. So it's free. There's no advertisements. There's no requirement for you to sign up for anything to utilize explore.org and it's really an opportunity for us to see unedited nature. And then my role with explore.org is to be sort of like an online interpreter for the wildlife. Due to my experience working as a park ranger in Katmai, I do a lot of programs about brown bears and salmon in conjunction with the park rangers at Katmai throughout the summer and fall. During the rest of the year, though, I might be interviewing people about the wildlife that they are trying to protect or work with, for instance. So we have some seasonal cameras that come on in the winter, like for manatees, for instance, in Florida. So I might be talking with like Save the Manatee Club or one of our other great partner organizations about the wildlife work that they do. So it's a rewarding job for me, because I get to learn so much, so it helps to stimulate my curiosity. But at the same time, I feel very fortunate to be able to share these experiences with people all over the world.

O'NEILL: And how do you feel that your work as a naturalist has, you know, sort of been informed by or sort of resulted from these experiences working with these bears up in Katmai?

FITZ: When I went to Katmai, I was largely ignorant of how wild animals are individuals. They compose a population, right? But just like us, you know, they're individuals in their own ways. But also, at the same time, my experience working as a ranger helped me understand that parks really do matter to everybody. They're valuable spaces to us, whether we have the opportunity to visit them in person. And I encourage everybody to get out into nature as much as you can. But also, there's these other nature-based experiences on the internet that are extraordinarily valuable as well, and I hope that through webcams and technology, we can share more of these amazing places with more people.

Katmai National Park and Preserve is a relatively undeveloped park, allowing for a healthy habitat for the animals there, including sockeye salmon and brown bears. (Photo: Joseph C. Boone, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: Mike Fitz is the creator of Fat Bear Week and a naturalist with explore.org. Mike, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

FITZ: You're welcome. It was fun to talk with you.

Related links:

- Visit explore.org

- Visit Katmai National Park and Preserve

- Visit Mike Fitz’ website

[MUSIC: Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, “The Bare Necessities – From “The Jungle Book”” on Disney Goes Classical, Universal Music Operations Limited]

DOERING: If you enjoy the stories you hear on Living on Earth, please consider signing up for our newsletter. You’ll never miss a show, and you’ll have special access to show highlights, notes from our staff, and advanced information about upcoming live virtual events. The Living on Earth newsletter is sent to your inbox weekly. Don't miss out! Subscribe at the Living on Earth website, loe.org, that's loe.org. By the way, you'll also find photos, links to more information, and a full transcript of every single show there. And we'd love to hear from you. You can write to us anytime at comments@loe.org. That's comments@loe.org.

[MUSIC: Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, “The Bare Necessities – From “The Jungle Book”” on Disney Goes Classical, Universal Music Operations Limited]

O’NEILL: After the break, how becoming “re-enchanted” with the natural world could help us be better citizens of Planet Earth. That’s coming up on Living on Earth. Stay with us!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Brandon Sanders, “The Tables Will Turn” on The Tables Will Turn, Savant Records, Inc.]

BirdNote®: Black Swifts Reach for the Moon

“Harvest moon” is a colloquial name for the full moons that appear in early autumn in the northern hemisphere. Many animals find their lives affected by the lunar cycles. (Photo: Jeff Hollett, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

O’NEILLL: The full moon on October 6th is known as the “Harvest Moon”, and it’s also the first supermoon of 2025, which is what we call it when the moon is relatively close to Earth and it appears a little bigger and a little brighter. There are all sorts of ways that life on Earth takes advantage of the regular cycles of the moon. The full moon triggers mass coral spawning within a few days, and many other creatures including horseshoe crabs and grunion fish lay their eggs during the resulting high tides. And there seems to be one bird species in particular that has a close connection with lunar cycles. Michael Stein has this BirdNote.

BirdNote®

Black Swifts Reach for the Moon

Written by Conor Gearin

[Whistling wind]

[Black Swift flock calls]

Black Swifts are extraordinary birds. They spend most of their lives in the air and migrate thousands of miles every year. But researchers have found that their lifestyle is even stranger than we once knew.

[Black Swift calls]

Scientists placed lightweight tracking devices on swifts nesting in Colorado. This let them study their movements once they reached their wintering grounds in Brazil. This provided unprecedented access to the swift's world in the skies. Astonishingly, Black Swifts spent over 99% of their time in the air during the winter, almost never touching the ground for months.

What’s more, the swifts flew to incredible heights, reaching the highest altitudes on nights when the moon was full – sometimes over 13,000 feet! It’s the first time scientists have seen birds changing their altitude along with the cycles of the moon.

A black swift in its nest. (Photo: Aaron Maizlish, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

[Black Swift calls]

It’s still unknown why the moon seems to draw Black Swifts high into the sky. It’s possible that insects, many of which can also fly thousands of feet in the air, are attracted to the moon, and swifts follow their insect prey upward.

What is clear is that these birds have abilities beyond what our eyes can see.

[Black Swift calls]

I’m Michael Stein.

###

Senior Producer: Mark Bramhill

Producer: Sam Johnson

Managing Editor: Jazzi Johnson

Content Director: Jonese Franklin

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Black Swift ML 363245171 recorded by Rose Ann Rowlett.

Black Swift Xeno Canto 677210 recorded by Richard E. Webster.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2023 BirdNote March 2023 / 2025

Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# BLSW-01-2023-03-10 BLSW-01

Reference:

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(22)00397-9

O’NEILL: For pictures and more, follow your excellent instincts to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related link:

Listen to this story on the BirdNote ® website

[MUSIC: Federico Miranda, “Kyoto Sky” on Baula Project: Corazones al Mar, Baula Producciones S.D.R.L.]

Encountering Dragonfly: Notes on the Practice of Re-Enchantment

Encountering Dragonfly: Notes on the Practice of Re-enchantment by Brooke Williams. (Cover: Design by Claudine Mansour, Courtesy of Brooke Williams)

DOERING: In lives full of screens and distraction, noticing what’s around us can sometimes feel like a rare event. It could be a scarlet leaf drifting from a tree in autumn, the song of a bird at your window, or the scent of rain. But for a moment, we look up, and we pause. Author Brooke Williams believes those flashes of attention are powerful and are imbued with more meaning than we often allow. We sat down at my home in Somerville, Massachusetts to chat about how he explores these ideas in his new book, Encountering Dragonfly: Notes on the Practice of Re-enchantment. Welcome to Living on Earth, Brooke!

WILLIAMS: Thank you for having me, Jenni. I'm really looking forward to this.

DOERING: Thanks so much for being here in person. So your fascination with dragonflies is the catalyst for some of the deeper philosophical explorations in this book. What is it about the dragonfly that has really captivated you and captivated humans for millenia?

WILLIAMS: Well, it goes back to a dream I had like 20 years ago. Prior to that, and ever since, I've always been enamored, obsessed, attracted to the natural world at every dimension. I was a field biologist in college, and any time I get a chance, I'm out looking at things and wondering about just the amazement of natural selection and evolution. And this dream I had had a dragonfly in it, and I realized that it was something that I've seen, I'm sure, dragonflies around, I mean, I was a field biologist, but the unique thing about the dream was, within minutes of waking I started seeing dragonflies everywhere, and I could count on one hand the number of memories I had about a dragonfly prior to the dream, and since then, there have been hundreds. So something happened with the dream, and that's where my obsession started, because I don't know about you, but writing is really hard, and books are really, really hard, and had I not had a couple of questions that I needed to answer, I probably wouldn't have written this book. And the two questions that I think of are, how much more can I learn about these amazing creatures? And the other question was, what happened during that dream that dissolved that border between my dream, unconscious world, and ordinary, everyday reality? So the book is really an exploration of those two questions.

Flame Skimmer. For author Brooke Williams, a dream about a dragonfly catalyzed his fascination with the creatures. (Photo: Brooke Williams)

DOERING: So your subtitle is, "Notes on the Practice of Re-enchantment." To what extent do you think we've become disenchanted as individuals and a society?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, that's something I've been thinking about a lot because going back to trying to understand what happened during that dream, it was years later I was at a lecture at the Harvard Divinity School listening to an academic talk about his book, which was called the myth of disenchantment. And according to most scholars, prior to modernity, the Earth was enchanted, and after modernity, it was disenchanted. Take trees, for instance. We could not cut down entire forests of trees to build forts and temples, whatever, if those trees still had spirits in them. So we just had to assume they didn't. And it's part of the Enlightenment. It's part of this idea that humans know everything, but this idea of an enchanted world where trees have spirits and everything is animated, goes clear back to our earliest beginnings, and we've lived like that for a lot longer than we've lived in a disenchanted world. And I think of it, a lot of it as the commodification of nature. When we started commodifying trees, that meant they couldn't have spirits, we objectified them. In other words, an object is, by definition, something that we manipulate and use for our advantage, as opposed to a subject which we interact with and we learn from. So it's a two-way relationship. I feel like that's a big important element of an enchanted world is living among subjects, as opposed to objects. This is just a massive shift in point of view, which I feel like our lives depend on at this point.

DOERING: Right. You talk in the book about this collective unconscious that you're tapping into, which dragonflies have helped you tap into, and I think part of that is the understanding of the world as enchanted, that like in our ancestors' lives, they understood the world to be enchanted, and we're just trying to tap into that and remember what that is like to have that perspective of the world. How would you describe what it has been like for you to try and tap into that layer of your life that previously kind of was unknown to you.

Male Widow Skimmer. Practicing “re-enchantment” involves actively noticing what draws your attention, author Brooke Williams says. (Photo: Brooke Williams)

WILLIAMS: It is a point of view shift. For instance, one of the major things that has happened to me is I've started to pay attention to the world and to things that happen as synchronicities, as opposed to coincidences, for instance. And you know, seeing a dragonfly or any sort of creature, a lot of people would say, well, that's just a coincidence. You happen to be in the same place at the same time, and you can look at it like that, but you can also look at it like something happened to your attention to where you notice this dragonfly because, or this other creature, whatever it is, because there's something you need to learn right now, or something that you need to pay attention to, and it's this idea of attention which is a positive thing. I mean, it's a real active phenomenon, as opposed to passive attention, which is what we're all suffering from now. I mean, we have these phones, and we just wait for these signals, whereas real attention is looking around and wonder what is trying to grab your attention. There's that writer, Arnold Mindell. He has this idea of flirting, which is not what we think it is, but flirting, from his perspective, is something flirts with you because you need it. It's demanding your attention for a purpose, where you can walk for a quarter mile with a group of kids and talk about what you saw, and no two kids saw the same thing, something different attracted each kid in a different way for some reason. I think it was Einstein, at least he gets credit for saying, I'm not sure he really did, that either everything is a miracle or nothing is a miracle. And if you get to choose, which are you going to choose? Why not pick everything as a miracle and start to like live as if that's the case?

DOERING: Why is marveling at the world and appreciating it something that our ancestors evolved to be able to do?

WILLIAMS: That's a good question. Our most distant ancestors, I feel like were living in bodies in a world that was all about survival of the fittest. And I feel like it was about, you know, paying attention, and it was about being one species among many. Everything that occurred within that day, within that moment, within those few feet around us, was potentially something that could feed us or kill us. And so we had to learn about everything. And I just feel like there's this amazing thing that happens with natural selection, for instance, where the things that we find most beautiful like flowers, like wildflowers, there's something that like taps into us with its beauty about a flower, and yet that flower is beautiful only as an unintended consequence of its ability to attract a pollinator so that it can pass its genetic material onto the next generation. And the fact that we find that beautiful and spectacular at times, to me, is like the miracle of life. Don't you think?

Female Autumn meadowhawk. Many cultures across space and time have considered the dragonfly a messenger between worlds. (Photo: Brooke Williams)

DOERING: Mm hm. So how do you think the dragonfly can be a gateway into learning how to practice re-enchantment? What can we learn from observing this creature?

WILLIAMS: Well, the simplest answer to that, I think, is that most cultures throughout the world think of dragonflies as the messenger between worlds. They spend most of their life as nymphs in ponds or in rivers at the bottom, and they molt where they grow so big they have to split open this casing, their carapace and break out of it into a bigger one. But at some point, something shifts, and instead of just molting from their casing, they crawl to the edge of the pond and up something vertical, and then they break open, like they always did, but this time, a dragonfly, an adult, breaks out, as opposed to another, a larger nymph. So there's this between worlds idea. So I really believe that one of the things that's really missing from our modern lives is this idea of the collective unconscious, which is the inner world. You know, this is a little weird, but what I do is, say they are messengers between the worlds. So many cultures believe that this is true, that there's got to be something to it, but it's something we can't prove, so we kind of ignore it as modern people, but say it is true. So when I see one, when my attention is attracted by a dragonfly, I do ask myself, is there something I'm not conscious of that I need to be right now?

WILLIAMS: To what extent do you think a cultural shift like re-enchantment could help us solve problems like the climate crisis?

Male Autumn meadowhawk. Author Brooke Williams suggests that an “evolution of consciousness” may be the key to healing our relationship with the planet. (Photo: Brooke Williams)

WILLIAMS: I don't know how it will happen, but earlier, we were talking about the commodification of nature and that we've commodified almost every natural resource. And if you extrapolate, then we've commodified carbon. And if that commodification has its roots in disenchanting the world, then the fact that re-enchantment might help us solve this carbon problem. And so what does that really mean? I don't really even know what it means, but I feel like just talking about it. I've had the privilege of going around and talking about this book a number of different places, and I always bring up the fact that I'm not really here to sell the book, although that's the idea, but I really want to build this idea of re-enchantment, and I think that the, I don't believe the world was ever disenchanted really. I think our lives have been disenchanted, and if we can re-enchant our own lives, then I feel like it's, that we really tap into this collective nature of who we really are of one species among many. And each of us has like this burning part of our body that still has its evolutionary powers, and we're still animals really in these like modern bodies, carrying around these computers all day, but we still have this spark of evolution, and I feel like that's what we need to tap into. And it's not going to take everybody, but I just think the right number of people that start thinking in these ways, will figure out how the planet can make the best use of them. And I think that's what we need right now. I think again, Einstein was credited with saying you can't solve problems with the same consciousness that you created them with, or something like that. And you know, maybe evolution is so broad, it's not just like biological. It may be evolution of consciousness that we need, and whether that's the thing that will save us, who knows, but what do we got to lose, right?

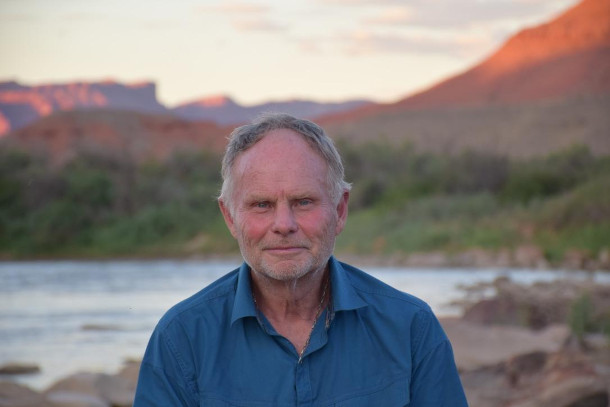

Brooke Williams is a Utah-based naturalist and the author of Encountering Dragonfly: Notes on the Practice of Re-enchantment. (Photo: Dan Schrag)

DOERING: Brooke Williams is the author of Encountering Dragonfly: Notes on the Practice of Re-enchantment. Thank you so much for joining us.

WILLIAMS: Thank you for having me, and thank you for all the great questions and the thought you put into this.

Related links:

- Find a copy of Encountering Dragonfly (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local independent bookstores)

- Learn more about Brooke Williams

[MUSIC: The Gothard Sisters, “Chasing the Sun” on Dragonfly, Gothard Sisters Music]

O’NEILL: Next time on Living on Earth, we remember the legendary primatologist Jane Goodall, who opened our eyes to the lives and behaviors of our primate cousins. Her deep care for other species and the planet was matched only by her care for humanity.

GOODALL: Even as I was learning about the problems faced by the chimps, I was learning about the plight of so many African people living in and around chimpanzee habitat, the crippling poverty, the lack of health and education facilities, the degradation of the land, as the human population grew and moved into chimpanzee habitat. And it came to a head when I flew over the tiny Gombe National Park, which had been part of a forest belt right across Africa. And when I looked down in the late 1980s, it was just a little island of forest surrounded by bare hills, more people than the land could support, too poor to buy food elsewhere, cutting down trees to make money from timber, or charcoal, or to make more land to grow food for their growing families. And that’s when it hit me. If we don’t help these people find ways of making a living without destroying the environment, we can’t save chimps, forests or anything else. And that was how Tacare began.

O’NEILL: We’ll hear favorite moments from past interviews with the late Jane Goodall and discuss her profound legacy for conservation and planetary care, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Tommy Emmanuel, “Angelina” on Endless Road, CGP SOUNDS]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Sophie Bokor, Daniela Fariah, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jade Poli, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth