Salmon Run Fattens Bears

Air Date: Week of October 3, 2025

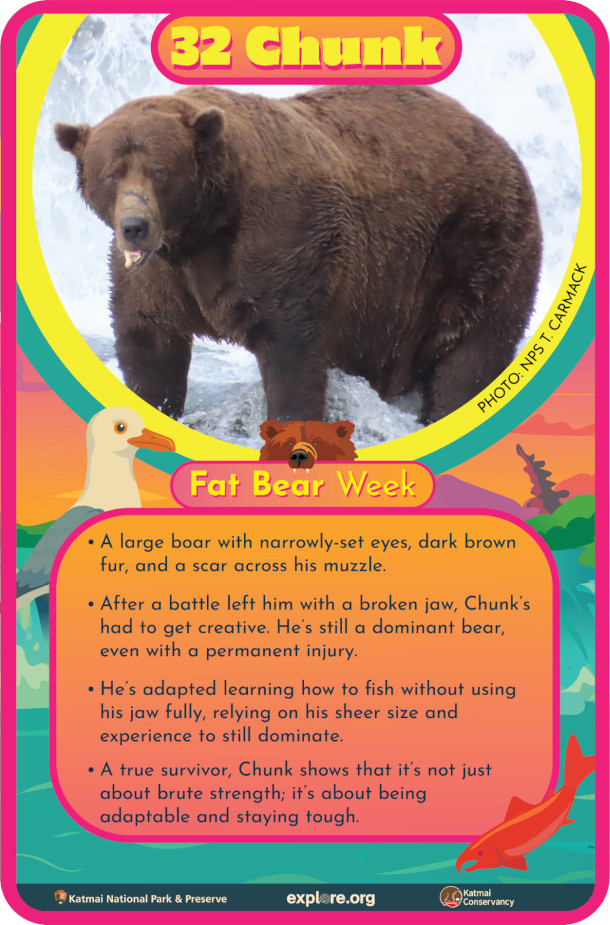

Every year, the brown bears in Katmai National Park and Preserve are viewable on live webcams via explore.org. In early fall, dedicated fans vote for their favorites to win the annual Fat Bear Week bracket competition. (Graphic: Courtesy of explore.org)

The champion of Fat Bear Week 2025 is officially number 32 - “Chunk”, a big male who overcame a broken jaw to take the prize. Mike Fitz, the resident naturalist at explore.org, launched Fat Bear Week as a ranger at Katmai National Park in Alaska. He joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain how this year’s strong salmon run in the Brooks River helped the local grizzlies bulk up.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Every year, Katmai National Park and Preserve in southwest Alaska hosts perhaps the fiercest bracket competition the animal world has ever seen. Fat Bear Week showcases the park’s famous brown bears, who have spent all summer feasting on fish to get ready for winter hibernation. Voters from around the world champion their favorites, sometimes on size alone, but also on the individual stories that you can follow by watching the online webcam footage. Mike Fitz is the creator of Fat Bear Week, which he started when he was a park ranger at Katmai National Park. He now works as the resident naturalist for explore.org, which hosts Fat Bear Week. He’s also written a book on these corpulent creatures, The Bears of Brooks Falls: Wildlife and Survival on Alaska’s Brooks River. And now he’s on the line. Mike, welcome to Living on Earth!

FITZ: Happy to be here, and Happy Fat Bear Week.

O'NEILL: Happy Fat Bear Week! So, the world has been celebrating Fat Bear Week now for over a decade. Tell us, how did you first come up with the idea for a contest like this back in 2014?

FITZ: Well, bears need to get fat to survive, right? Fat is the fuel that powers their ability to survive winter hibernation. And when I was a ranger at Katmai, we would see many of the same bears in early summer and in late summer, and we would see their body mass changes. So that was one of the things that we always talked about with the park visitors. But in late September 2014, I was browsing webcam comments on explore.org, and I saw a pair of screen captures from the webcams of the same bear from an early summer photo and a late summer photo, and the person remarked, hey, look how fat this bear got. Something in my brain clicked at that moment, and I thought, wouldn't it be fun if we allowed the webcam audience to decide who was the fattest and most successful Brooks River bear of the year? So we came up with this idea for a thing called Fat Bear Tuesday. It was a one-day tournament. We put it on Katmai's Facebook page, people voted with their reactions or likes, and that day, I decided, this needs to be expanded into a whole week to give more people the opportunity to participate. And that's how the idea for Fat Bear Week was born.

O'NEILL: I love it. I love just a full bracket, and you just get to look at all these great photos and well, congratulations to this year's winner of Fat Bear Week, 32 Chunk. What can you tell us about 32?

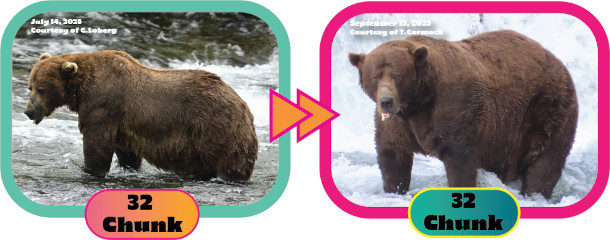

FITZ: He's one of the largest bears at Brooks River, and has been so for a number of years. So Chunk is a big bear, like a 1200 pounder at least. He's probably fatter than that, but we don't know for sure, but at least 1200 pounds. He's one of the more dominant bears at the river. He's been the river's most dominant bear, like last year in 2024 he was. This year, however, he had a pretty severe setback in June when he broke his jaw. We don't know how he broke his jaw, but the timing of it and the nature of the injury strongly suggest he broke it in a fight with another bear. So he's had to deal with the pain, the suffering, but Chunk is powering through it, and he's done so throughout the year. He's gotten really, really fat, and he's done remarkably well for himself this year. So I think with his, his resilience, his perseverance, I think that story resonated with a lot of Fat Bear Week voters. And Chunk has been like the runner up, I think, the past two years in 2023 and 2024, so this seemed like it was his year.

Before and after photos of 32 Chunk, this year’s Fat Bear Week bracket champion. 32 Chunk had been runner up in years past. (Graphic: Courtesy of explore.org)

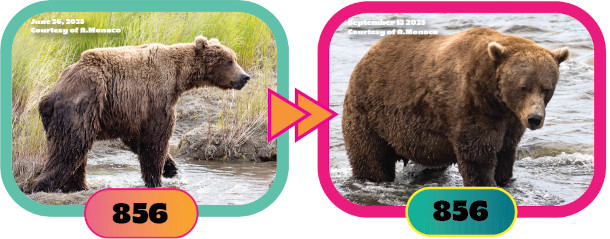

O'NEILL: And Mike, tell us about our runner up here.

FITZ: 856, his story resonated with people because he's an older adult male, so he can't compete like he had in the past, and he was the river's formerly most dominant bear. I mean, he became hyper dominant, like in 2011 and just like was at the top, the very tippy top of the bear hierarchy at the river, and he held that position for more than a decade.

O'NEILL: Now, Mike, I'm curious why some of these bears, like Chunk, get names and others are just known by sort of these numbers.

FITZ: There's no official nicknaming process with the national park staff at Katmai. So some of the bears just kind of get nicknames over time informally. Chunk actually got his nickname just as a memory aid for the biologists who were identifying bears. So he was just on his own for the first time in 2007 as a two and a half year old, and he was pudgy then, and he's kind of grown into that nickname since that time. 856 has never had a nickname, and I can't actually imagine calling him anything else than 8-5-6 or 856, he's just always going to be that number for me.

O'NEILL: And so in order for these bears to get so big, what exactly are they eating?

FITZ: Brown bears are omnivores, just like people, so they eat a wide variety of foods, but in Katmai National Park, salmon are especially important to brown bears, so they have a higher percentage of meat and protein in their diet compared to a lot of brown and grizzly bears throughout North America. And that's one reason why they can grow so large is because they have access to ample runs and large runs of salmon. And salmon are such a great food for bears because they're not only high protein, but they're also very high fat as well.

O'NEILL: Mmhmm. And so, on a daily basis, how much salmon do these bears tend to eat?

856 was this year’s Fat Bear Week bracket runner-up. Though he’s never won the competition, 856 had been the dominant bear in the Brooks River for a number of years. (Graphic: Courtesy of explore.org)

FITZ: Depends on the bear, depends on the day it's having, depends on the amount of fish that are moving through the river that day. But on a good day, a bear can easily catch 20 to 30 salmon. So yeah, they'll eat a lot of salmon. I think the record that I saw personally was a bear that ate like 42 salmon in about five hours. These aren't small fish either. I mean, a sockeye salmon can average about five pounds in Brooks River.

O'NEILL: In order to support that volume, it sounds like the salmon run must do, you know, pretty well each year. How was it this year?

FITZ: This year's salmon run in Brooks River was exceptional. It was so great. I mean, we saw wall to wall salmon, like from early July until like, the middle of August, and hundreds of salmon jumping the waterfall every minute. So it was really incredible to watch. And Bristol Bay, the Katmai region, is home to the last great salmon run left on earth. One of the things that was special about Brooks River this year, though, and the salmon run, was that there were so many fish in the river that the bears were essentially released from food competition. In a normal year where there are fewer salmon, or maybe just waves of salmon moving into the river, bears will go to Brooks Falls, and they'll compete for the most productive fishing spots. We didn't really see that in early summer this year, because there was no single good fishing spot. Fishing was good everywhere along the river, we saw bears expressing a lot more tolerance, a lot more playful activity between bears. And to me, that was another demonstration of their behavioral flexibility, their behavioral plasticity. They are adaptable creatures. They're very smart animals, very sentient and aware of their environment and the circumstances that they adapted to this summer, I think, was just another great example of that.

O'NEILL: And by the way, the parts of the salmon that these bears discard, what happens to those?

FITZ: There's no waste in nature. So those parts of, the discarded parts of the salmon are cleaned up by scavengers. Maybe that's a hungrier bear downstream. Maybe that's a bald eagle, maybe it's a gull. Could be, you know, another animal or a decomposer, especially. One of the more fascinating aspects of this dynamic as well is that plants grow faster in areas where salmon are coming back into these watersheds. So bears, they are maybe carrying salmon carcasses into the forest or the marshes along a river, for instance, they're also carrying salmon nutrients through their digestive system, so they will leave deposits in their scat out in the forest, or they'll urinate in the forest. And that helps to boost the productivity of plant life around these watersheds as well. So salmon are really kind of like the gift that keeps giving.

O'NEILL: So we're talking to you right now at the beginning of fall. What are these bears going to be doing now? Walk us through the beginning of fall to next summer.

FITZ: So they're storing up basically a winner's worth of food to survive that period of time where they have no access to food. So yeah, right now they're going to be concentrating more and more on eating. Over the next several weeks though, their metabolism is starting to ramp down. It's a really kind of slow transition down into their hibernation mode. Their appetite will decline. They'll eventually wander off to their dens. They will build and construct their dens on steep slopes that collect and hold a lot of snow. In Katmai, they're basically just digging a den straight into the earth, straight into a hillside, and then they'll eventually go in there, and they'll begin hibernating, generally in November for most bears in Katmai, although it ranges from maybe like late October into December, when they begin hibernation.

O'NEILL: And to what extent are you able to monitor them during their hibernation period? And I don't just mean you and the scientists who work with them, but what about the public? Are there any live cams that we'd be able to use to check up on our favorite bears? Or do we just have to wait until next year?

FITZ: Yeah, we're gonna have to wait until next year. In Katmai National Park, the locations of bear dens are too unpredictable for us to say, hey, let's put a cam in this location. But we've learned a lot from webcam observations of bears in dens in other places. And then also, sort of like the miniaturization of technology has allowed scientists elsewhere, like in Scandinavia, to actually implant like heart rate monitors and things like that on brown bears and radio and GPS collars, for instance, to know where they're denning, and then you can check and see you know what the heart rate monitors are telling us about brown bear physiology and metabolism inside of the den. So with brown bears in Katmai, we can kind of only extrapolate about what their hibernation experience is like, and that's based on observations from either like captive facilities or some more rarely, some wild observations in other parts of the world.

Fat Bear Week would not be possible without a healthy sockeye salmon run on the Brooks River. (Photo: Courtesy of Russ Taylor, Katmai National Park and Preserve)

O'NEILL: And right now, the world is facing a few ecological crises. I'm talking climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution. How are the bears faring with these issues on the rise?

FITZ: In Katmai National Park, they're doing really well, and that's largely because the ecosystem there is intact, right? Katmai is a very remote National Park. It's almost exclusively undeveloped. There's hardly any trails. You have to fly or take a boat to get there. So the watersheds are healthy. They're unengineered. The salmon runs right now are ample, but that doesn't mean that they're not facing threats due to climate change, for instance. The hydrology of the park is certainly changing. Glaciers are melting. Ice cover along the volcanoes has declined significantly over the last century. We know that the lakes and rivers are getting warmer. We know that the oceans are getting more acidic as they absorb CO2 from the atmosphere. All of those things have this significant potential to disrupt the sockeye salmon run in Bristol Bay. So they're doing well in some respects, but also, you know, the future does, does pose some significant challenges for them.

O'NEILL: Well, it's good to hear that these bears are doing pretty well, all things considered. But for fans who pay attention, maybe just during Fat Bear Week here in September, what can they do the rest of the year to show some support or appreciation for these bears?

FITZ: I think there are several things that people can do. One of the things that we can do is just share, sort of like the, the story of Katmai and Bristol Bay and the Brooks River bears and the Fat Bear Week bears with other people. And that's really special, right? You know, with the biodiversity loss and the extinction crisis happening around the world, often we get overwhelmed with these doom and gloom stories, but there's a lot to celebrate. There's a lot to save out there. And I think we can look at sort of like Bristol Bay, and we can look at Katmai as one of those examples of things that we can work towards in other places as well.

O'NEILL: And Mike, in addition to being the, you know, creator of Fat Bear Week and an author, you currently work as a naturalist with something called explore.org. Tell us a little bit about your role there, please.

FITZ: Yes, I'm the resident naturalist with explore.org, and we are a philanthropic organization that specializes in live nature cams of animals in nature. I think we have something like, currently, 190 live cams around the world, so there's always something to watch. For example, like in the morning, maybe before the brown bear cams in Katmai go online, I might go to Africa, for instance. I was actually watching hummingbirds at a feeder in southern Arizona this morning before we talked. So it's free. There's no advertisements. There's no requirement for you to sign up for anything to utilize explore.org and it's really an opportunity for us to see unedited nature. And then my role with explore.org is to be sort of like an online interpreter for the wildlife. Due to my experience working as a park ranger in Katmai, I do a lot of programs about brown bears and salmon in conjunction with the park rangers at Katmai throughout the summer and fall. During the rest of the year, though, I might be interviewing people about the wildlife that they are trying to protect or work with, for instance. So we have some seasonal cameras that come on in the winter, like for manatees, for instance, in Florida. So I might be talking with like Save the Manatee Club or one of our other great partner organizations about the wildlife work that they do. So it's a rewarding job for me, because I get to learn so much, so it helps to stimulate my curiosity. But at the same time, I feel very fortunate to be able to share these experiences with people all over the world.

O'NEILL: And how do you feel that your work as a naturalist has, you know, sort of been informed by or sort of resulted from these experiences working with these bears up in Katmai?

FITZ: When I went to Katmai, I was largely ignorant of how wild animals are individuals. They compose a population, right? But just like us, you know, they're individuals in their own ways. But also, at the same time, my experience working as a ranger helped me understand that parks really do matter to everybody. They're valuable spaces to us, whether we have the opportunity to visit them in person. And I encourage everybody to get out into nature as much as you can. But also, there's these other nature-based experiences on the internet that are extraordinarily valuable as well, and I hope that through webcams and technology, we can share more of these amazing places with more people.

Katmai National Park and Preserve is a relatively undeveloped park, allowing for a healthy habitat for the animals there, including sockeye salmon and brown bears. (Photo: Joseph C. Boone, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: Mike Fitz is the creator of Fat Bear Week and a naturalist with explore.org. Mike, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

FITZ: You're welcome. It was fun to talk with you.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth