September 5, 2025

Air Date: September 5, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

PFAS Polluters Pay Up

View the page for this story

New Jersey officials are calling its $2 billion settlement with major manufacturers of PFAS “forever chemicals” the largest environmental settlement ever won by a state. Shawn LaTourette, New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner, discusses with Host Paloma Beltran the legacy of industrial contamination in the state and how the settlement is expected to pay for cleanup as well as restoration of degraded ecosystems. (12:58)

Nickel Mining's Toll

/ Alon AviramView the page for this story

Nickel is a key mineral for the clean energy transition but can come at a cost to local communities because of how polluting nickel mining operations can be. In Indonesia leaked company documents reveal that Harita Nickel, one of the world’s largest nickel mining companies, knowingly polluted fresh water sources. Alon Aviram, a reporter with the nonprofit journalism newsroom called The Gecko Project, joins Host Paloma Beltran to discuss their investigation. (10:36)

Tylenol Upcycled From Plastic

View the page for this story

Scientists in the UK were able to use genetically modified bacteria to turn plastic bottles into the common pain reliever acetaminophen, also known as paracetamol and Tylenol. Lead researcher Stephen Wallace, a Professor of Chemical Biotechnology at the University of Edinburgh, speaks with Host Jenni Doering about the potential applications of this biotech breakthrough. (08:42)

Birdnote®: Poisonous Birds

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Nature has been tinkering with biology and chemistry for as long as life has existed on this planet. And as BirdNote®’s Michael Stein reports, some species have evolved to make use of special chemical weapons – a.k.a., poison. (02:19)

Roadless Rule Under Fire

View the page for this story

With an unusually short period for public comments the Trump administration is moving to repeal the “Roadless Rule,” which currently protects over 45 million pristine acres of national forests from access roads for logging. Randi Spivak, the public lands policy director for the Center for Biological Diversity, joins Host Jenni Doering to explain the potential consequences for critical habitat, watersheds, carbon storage and recreation if the Roadless Rule is repealed. (11:02)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250905 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Bletran, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Alon Aviram, Shawn LaTourette, Randi Spivak, Stephen Wallace

REPORTERS: Michael Stein

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

New Jersey wins a major environmental settlement over “forever chemicals.”

LATOURETTE: They sent, DuPont, that is, sent their PFAS waste from elsewhere in the country. In effect, DuPont used the state of New Jersey as the PFAS toilet for the country.

DOERING: Also, a biotech breakthrough turns plastic waste into Tylenol.

WALLACE: So by taking this technology and programming bacteria, we not only defossilize the manufacture of this worldwide essential medication in a way that doesn't release climate emissions, but we also clean up plastic waste from the environment at the same time.

DOERING: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

PFAS Polluters Pay Up

The Repauno Port & Rail Terminal was once a DuPont chemical manufacturing facility. The land is being cleaned up for PFAS contamination attributed to DuPont and its spinoff, Chemours. The site is currently being operated as a port facility by FTAI Instructure Inc., which acquired the property in 2016. DuPont and its subsidiaries have agreed to spend $1.2 billion for the cleanup of various sites across the state. (Photo: Office of the NJ Attorney General)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Our first story today is about a major victory for the state of New Jersey over PFAS contamination. As you know Jenni, those are so-called “forever chemicals” that are found in everything from rain jackets, to firefighting foam, to nonstick cookware.

DOERING: That’s right, and they’ve now spread throughout our environment and our bodies. You know, I’ve been thinking a lot about PFAS since we know these chemicals are linked to numerous health problems – cancer, hormonal imbalances, and weakened immunity. And this weekend I finally decided to retire the last two nonstick pans I own. So I’m committing fully to stainless steel and cast iron cookware.

BELTRAN: Hey, that’s a big step! I made the switch a year ago, but it just takes a little more elbow grease to clean those up. But you know Jenni, I’ve realized that hot water and vinegar act like magic when it comes to cleaning stainless steel.

DOERING: Ooh, that’s a great tip!

BELTRAN: Yeah, please try it! And, you know, I haven’t quite mastered the do’s and don’ts of cooking with cast iron, but I believe in us Jenni!

DOERING: You know what, I love that spirit! You’re giving me a lot of hope for moving past the PFAS in cookware. Anyway, I guess when it comes to PFAS there are much bigger fish to fry than a couple of frying pans. And this settlement New Jersey reached with chemical manufacturers is a really big deal, huh?

BELTRAN: It’s huge, we’re talking about $2 billion, and officials say it’s the largest environmental settlement ever won by a state. DuPont, its spinoff Chemours, and Corteva have to pay the state $875 million to settle claims and provide up to $1.2 billion in cleanup costs. New Jersey has won other PFAS settlements in the past. But for this latest settlement, a public comment period runs through November 1st and a court will need to give final approval. Joining us now to discuss is Shawn LaTourette, the state Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner. Welcome to Living on Earth, Shawn!

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner Shawn M. LaTourette was appointed on June 14, 2021. A lawyer and a policymaker with more than two decades of experience, LaTourette began his career defending victims of toxic exposure, including organizing and advocating for the needs of vulnerable New Jersey communities whose drinking water was contaminated by petrochemicals. (Photo: New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection)

LATOURETTE: It's a pleasure to be with you.

BELTRAN: Tell us more about the contamination here. You know, how did PFAS exposure impact the residents of New Jersey?

LATOURETTE: So New Jersey is home, or rather, was home to a bit of a PFAS manufacturing epicenter in the United States, particularly in the southern half of the state. There were several facilities, DuPont being one of them, but there were also other manufacturers located in factories along the Delaware River in southern New Jersey and also along the Raritan River in Bay in central New Jersey, and we began understanding the existence of PFAS contamination in the early to mid 2000s. In fact, New Jersey conducted the first statewide assessment of PFAS affecting water, I believe, in the country, in about 2006 and that sampling of water systems led us to begin expanding our own groundwater monitoring networks for PFAS sampling, and we began to test for the occurrence of certain PFAS compounds in various media, including in soils and including in biota and in shellfish, for example. And we came to find that New Jersey is in many ways, ground zero for some of the worst impacts of PFAS due to that manufacturing history. And one example of that would be the case that went to trial was the first one that went to trial against DuPont. It was concerning a site called the chambers works in southern New Jersey. It is a site that is over 1,300 acres. It's the size of a small town, and it sits at the foot of the Delaware Memorial bridge that connects New Jersey to the state of Delaware, goes over the Delaware River. And DuPont operated that site for a long, long time. They produced chemicals like Teflon, for example, and many other chemicals. And at that site, they had a large wastewater treatment plant, and they sent, DuPont, that is, sent their PFAS waste from elsewhere in the country, from other factories in West Virginia and North Carolina, et cetera. They sent their PFAS waste to be disposed of through the wastewater plant at chambers works. In effect, DuPont used the state of New Jersey as the PFAS toilet for the country. And so we find this contamination all over South Jersey, and of course, in other places as well. We find PFAS contamination in places you wouldn't expect, like in the surficial soils of remote New Jersey forests that should be pristine.

BELTRAN: Shawn, PFAS is deemed a forever chemical. It's pretty ubiquitous. What will the restoration process entail?

Chambers Works is a 1,455-acre complex located along the eastern shore of the Delaware River by State Highway 130 (Shell Road) in Deepwater, New Jersey. East of the Chambers Works Complex are industrial, residential, and recreational areas. North of the complex are residential areas, with the Delaware River to the west. (Photo: Office of the NJ Attorney General)

LATOURETTE: It's a lot more complicated than some of our traditional chemicals. New Jersey was once, less so now, a state pretty dense with chemical manufacturers, and we have a long history of making sure they clean up after themselves. But PFAS isn't like petroleum hydrocarbons or, or metals or PCBs, because they circulate so widely throughout environmental media. And so we have to go through a process where we are identifying the major sources of PFAS and interrupting them from becoming continuing sources to another part of whether it's the water cycle or the carbon cycle. I'll give you an example. If a company is still making things with some types of PFAS, and they discharge their wastewater through a treatment plant, and that goes into the waterway, that PFAS is now circulating through the waterway, and it's going to get picked up by a drinking water system, and then that drinking water system is going to have to pay to put on treatment to clean that PFAS out. But what if we catch it before it gets to the waterway and we interrupt the PFAS loading at that point in the water cycle? We've got to do this type of work at multiple points within the water cycle, within the carbon cycle, so on and so forth. We've got to do things like putting in sentinel wells around some of our oldest landfills that could be leaching PFAS that is then reaching the water table, which is also a source of drinking water.

BELTRAN: And from what I understand, this settlement provides money for natural resource restoration. What does that mean? You know, what will that process look like?

LATOURETTE: Natural resource restoration is different than cleanup. Natural resource restoration is based in a really simple principle, a principle of trusteeship, meaning, not unlike your 401k, right, or your investment accounts that a bank is holding for you in trust, and they have to take good care of it, the state government holds all of the natural resources in trust for the people, and if they're harmed, we have to pursue, we are obligated to pursue those who harmed the resources to pay, to clean, not just clean them up, but to restore the value of those resources. So if pollution degrades a wetland, we need to make you create a new wetland that provides those same natural resource benefits for the public, because it's the public's resource right, our air, our land, our water, our wetlands, our natural and historic resources. They don't belong to the government. They belong directly to the people, and it's just the job of folks like me to take good care of them, and if they're hurt, it's the obligation of the natural resource trustee to get your resources back.

BELTRAN: You know, Sean, this seems like a turning point for PFAS accountability. What can other states learn from New Jersey?

LATOURETTE: I think what other states can learn is not something they don't already know. Other states that have been impacted by PFAS to the extent New Jersey has, and there are other states that have experienced such impacts. North Carolina, West Virginia, Minnesota, right the list goes on, particularly where there were industrial sites, you're going to see those impacts be worse. So there's a lesson for the states that have had a history of industrial PFAS manufacturing, but there's also a lesson for states that didn't have that industrial history, but still have a perpetuating PFAS problem, because it is diffuse within our environment. And in each of those instances there is an important lesson that comes out of this, which is number one, the public expects what my grandmother did. And by that, I mean the public expects of their government—our department of environmental quality or protection—the public expects their government to hold folks accountable to ensure that they clean up after themselves and that the public will support you if you have to take on a big company to make them follow my grandmother's rule, to clean up after themselves. And the other lesson, I think, is that these companies, who know they have these liabilities, they will come to the table. You may have to fight with them for a few years and go through a little bit of litigation, but the science is clear. The stuff is harmful, and they knew it was harmful, and they kept making it anyway, and they kept putting it in products anyway, because the getting was just too good.

E.I. DuPont De Nemours & Company manufactured explosives at the 576-acre site in Pompton Lakes, New Jersey from 1902-1994, when it closed. DuPont manufactured lead azide, aluminum, bronze shelled blasting caps and produced metal wires and aluminum and copper shells. (Photo: Office of the NJ Attorney General)

BELTRAN: And how will the people of New Jersey benefit from this decision? How will they benefit from this settlement?

LATOURETTE: Well, they're going to have cleaner water, that's for sure. And one of the points that's really important about that. I think about small rural communities where people are not connected to a public water system, and how we have aquifers here in New Jersey and around the country that are contaminated with PFAS above safety standards, many of them don't know, right? There's no government entity in many instances, unless you're selling your house, coming to test your water for you, if you have a private well, but you can and should test it yourself, and you should do it every year. I think that for those communities in particular, there's a new resource for them that didn't exist before at all. Public water systems, they've always had access to funding from the federal and state governments to improve their drinking water treatment. But potable well owners represent 15% of New Jersey. They don't have that level of support, and this means they'll get it. So we're taking care of folks who've been forgotten, maybe even written off. And we're not just going to make sure the water is clean. We're going to enrich their environment, whether that is new rain gardens in their community that help absorb pollutants instead of circulate them, whether it's making sure that old landfill in your town that nobody ever checked to make sure it was closed right, make sure it's not leaching into your waterway. I think there's a lot of positive impacts that will play out over several years coming from this, but at the same time, the PFAS liabilities are large, and they are forever chemicals and new treatment that gets built because of this settlement will have to be operated into the long term. This settlement won't fix everything, but it gives us one heck of a big head start.

BELTRAN: Shawn LaTourette is Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. Thanks for joining us.

LATOURETTE: It's a pleasure. Thank you.

Related links:

- Read the Dupont Statement

- Waste 360 | “New Jersey Lands $2B PFAS Settlement From DuPont – While Water Systems’ Settlements Roll In”

- Inside Climate News | “Amid Federal PFAS Rolls backs, New Jersey Scores Record $2 Billion DuPont Settlement”

- Read the Statement from the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection

[MUSIC: The Jazz Seekers, Niclas Knudsen, “Happy House” on Divine Beasts, AMM]

DOERING: Coming up, while New Jersey has its sights on cleaning up past pollution, a community in Indonesia is in the midst of a water contamination crisis from nickel mining. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Jazz Seekers, Niclas Knudsen, “Happy House” on Divine Beasts, AMM]

Nickel Mining's Toll

Nickel mining is an environmentally destructive process that can create conditions in which Chromium-6 is formed. (Photo: The Gecko Project)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

The silvery-white metal nickel is an important component of wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicle batteries. So, it’s a key ingredient in the clean energy transition, but it comes at a cost to local communities because of how polluting nickel mining operations can be. Leaked company documents reveal that Harita Nickel, one of the world’s largest nickel mining companies, knowingly polluted fresh water sources for the town of Kawasi on the Indonesian island of Obi. Alon Aviram is a reporter with the nonprofit journalism newsroom called The Gecko Project, which investigated the pollution from Harita Nickel. Alon, welcome to Living on Earth!

AVIRAM: Pleasure to be here. Thanks for having me.

BELTRAN: So you were part of this reporting team that traveled to the Obi village after leaked documents exposed water pollution linked to the nearby mining company Harita Nickel. How were local communities affected by this contamination?

AVIRAM: Behind Kawasi Village, which is a small village on the western shores of the island, is a large company, one of the most powerful mining companies of Indonesia, Harita Nickel. And we ended up working discreetly with an Indonesian reporter who went to Obi and interviewed people on the ground and collected information as part of the reporting team. The general picture is that the people that they interviewed who, you know, welcomed them into their homes and took them around the village. They described a situation where illnesses are endemic. Many people have skin irritation, you know, their repeated respiratory issues. One woman who was interviewed, a mother called Nurhayati, a local resident who we quote in our piece. You know, she talks about having this chronic cough, and some people have taken in Kawasi are purchasing kind of filtered water instead of using the drinking spring. But one person who we spoke to, a local fisherman, he said that he simply couldn't afford to be buying his own water. So, there's also like a division there within the community where, you know, people who can afford to buy drinking water are definitely doing that, and others aren't, and then many are still using it for cooking and washing and so on and so forth. But yeah, certainly the people that our reporter spoke with described a situation which didn't sound like a just transition.

BELTRAN: So chromium six plays a key role in this story. It's a byproduct of mining, and a lot of people may recognize the name because of the Erin Brockovich movie or the Erin Brockovich case. What are some of the dangers associated with this chemical, and how is it impacting water supplies across Obi village?

A local Kawasi resident stands beside white pipes, which transport water from the Kawasi spring to neighboring villages. (Photo: Rifki Anwar, The Gecko Project)

AVIRAM: So yeah, hexavalent chromium. I'll call it chromium six, because it's just a bit of less of a mouthful. It's a carcinogen. It's a toxin which can have like severe health effects if inhaled or consumed at high levels, and chromium is a naturally occurring metal in the ground there and in a lot of like nickel mining areas. And when it's in the ground, it's in a nontoxic form, predominantly, the chromium oxidizes and can then mobilize or turn into chromium six, which is the toxic form of chromium. So you have this situation where the mining can then trigger this occurrence of chromium turning into chromium six, and in an area of like high rainfall, which Obi is, it's in the tropics, what you find is that water kind of comes spilling down the hillsides, down ravines, across the lands which is being mined, and across the areas which are storing waste. And then this can carry the chromium six into surrounding waterways and into the ground and environment. And this is what was being identified by Harita in internal emails and documents. And this was like happening again and again, from 2012 onwards in the files that we saw.

BELTRAN: And according to your investigation, what evidence is there that Harita Nickel, the mining company, was responsible for the contamination?

Alon Aviram is a reporter with the nonprofit journalism newsroom called The Gecko Project (Photo: Alon Aviram)

AVIRAM: It's hard to establish conclusively whether health symptoms that are like widely reported by local people is directly caused by a single pollutant like chromium six, but we spoke with a range of experts, toxicologists, epidemiologists, and a range of other qualified experts who reviewed the data that came from Harita, you know, this was company data from Harita itself. They looked at the figures that they had recorded from spring water monitoring samples, and they said that while you couldn't say categorically that people would experience, you know, various illnesses and adverse health effects from drinking this water that it certainly increased the risk of them experiencing various health conditions. So the bottom line is, we don't know without more data on like, how the people of Kawasi have been impacted by this, but they have certainly been put at greater risk by these elevated levels.

BELTRAN: How did Harita, this mining company, how did they react once they knew that high levels of chromium were present in the water supply?

AVIRAM: So Harita when it realized that there were high levels of chromium six coming out of wastewater. It started to introduce like various measures to try and mitigate that, to try and reduce the levels. It had leachate ponds, sediment ponds. It used chemical fixes to try and reduce the levels and even wetlands to try and neutralize the pollutant as well. But it had limited success, and there were repeated spikes in chromium six that it was detecting through its own tests. It had its own technicians out in the field taking samples and then testing those in its own laboratories, and then it was feeding this information kind of up the chain to senior environmental managers within the company, and highlighting that these were levels that were above the legal limit, and on repeated occasions, they attributed this contamination to its own operations.

Plumes of smoke drifting above Kawasi village serve as a constant reminder of Harita Nickel’s presence. (Photo: Rifki Anwar, The Gecko Project)

BELTRAN: And how did local communities from Kawasi react? To what extent were they aware that their water was being contaminated?

AVIRAM: It's one of those things where people can they can tell you what the water tastes like, what it smells like if it's changed color. And people would say that, you know, in interviews that we carried out, people talk to us about their kind of suspicions that something was up that, you know, people talked about the water having changed in taste and smell and color, since, you know, when they were kids, when they would just drink straight from the local river and so on and so forth. But they weren't sure if there had actually been, you know, pollution, or they couldn't categorically prove it with, like, hard data. And I should clarify that the repeated high levels of chromium six in drinking water was throughout 2022 so from February ‘22 to February ‘23 and what preceded that is about a decade's worth of repeatedly high levels of water contamination in wastewater, in river water. The likely cause was that the aquifer itself had been contaminated, but they hadn't told people at the time, we've got a chromium six problem in your drinking spring. We're trying to establish what the problem is, and we'll keep you updated. And here's some bottled water instead.

BELTRAN: You know, Alon, nickel is meant to be one of the transition metals to move away from gasoline-powered vehicles and expand electric vehicles, and a lot of battery producers have pledged to source materials responsibly. What do you make of these stories where mining companies are polluting neighboring communities?

AVIRAM: I think we have a situation where there's definitely a need to decarbonize, and people are on the streets of London, Washington, Paris, everywhere around the world are flocking to buy EV cars. And on the face of it, it seems like a good thing, we're stepping towards the green transition, but there are complicated layers to this, and the underbelly of this transition is one that deserves more scrutiny, because fueling this transition are often environmental violations and issues that are exported abroad to places like Indonesia and other countries where critical minerals transition minerals are being mined and processed, and you don't see that when you're driving your EV, your Tesla, your Mercedes Benz, your BMW, but I think there's a duty on car companies, on various actors within the supply chain, to ensure that the companies that are doing the mining, doing the refining in places like Indonesia and places like Obi Island are carrying out their activities, their their business operations, in a way which benefits local people and doesn't harm the environment. And it's this sort of dichotomy of jeopardizing a local ecosystem for the benefit of global carbon emissions is one that needs to be contended with more seriously. There are real disparities in terms of, you know, who's accumulating wealth and what does life look like for the residents who are surrounded by these metals which are fueling the EV boom.

A Kawasi village local looks out at the Akelamo River on Obi Island. (Photo: Rifki Anwar, Mongabay Indonesia)

BELTRAN: Alon Aviram is a reporter with the nonprofit investigative journalism newsroom called The Gecko Project. Thanks so much for speaking with us today.

AVIRAM: It was a real pleasure. Thank you so much.

BELTRAN: The Gecko Project and its partners in the investigation reached out to the Indonesian government prior to the release of the report but did not receive a response. During the summer months Indonesia experienced heavy rains, flooding several villages where Harita nickel operated. Making matters worse, a sediment pond built by the company to contain runoff was breached. Mudslides and flooding are common across Indonesia but according to Earthworks, “Residents say mining activities and the clearing of forests by Harita Group and its subsidiaries” contributed to the floods.

Related links:

- Read about The Gecko Project’s nickel mining story

- In response to allegations, Harita Nickel shared this article in lieu of a statement

[MUSIC: eleventwelfth, Reruntuh, “MASA” on SIMILAR, Angular/Momentum]

Tylenol Upcycled From Plastic

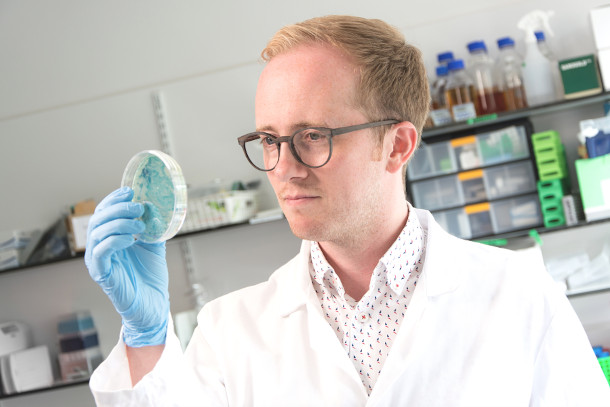

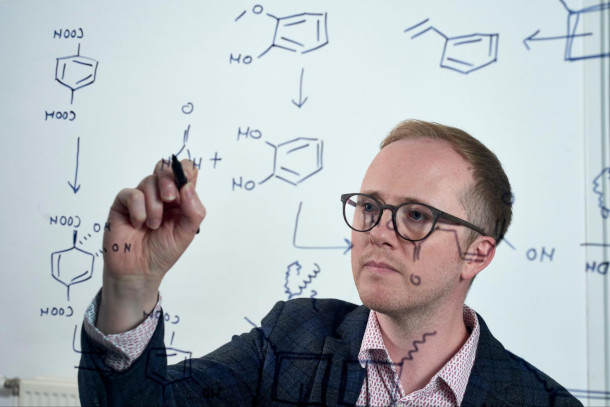

The strain of E. coli bacteria used in Dr. Wallace’s study is different from the strain that causes human disease. In fact, by genetically engineering it, Dr. Wallace’s team was able to use it to turn plastic waste into acetaminophen. (Photo: The University of Edinburgh)

DOERING: As the planet becomes overwhelmed by plastic waste, some researchers are using creative chemistry and biology to come up with possible solutions. Scientists in the UK recently published a paper in the journal Nature Chemistry describing how they turned plastic bottles into the common pain reliever Tylenol, also known as acetaminophen or paracetamol. Their tiny comrades in this remarkable transformation were genetically modified E. coli bacteria. Every plastic bottle could be turned into two acetaminophen pills. What’s more, one of the genes that enabled those bacteria to make Tylenol came from mushrooms! Thanks to advances in DNA editing technology, researchers were able to insert this mushroom gene into the bacterial genome. With us today is Stephen Wallace, the lead author on the paper and a Professor of Chemical Biotechnology at the University of Edinburgh. Hi Stephen, and welcome to Living on Earth!

WALLACE: Hey, Jenni, thanks for having me.

DOERING: So you feed E. coli plastic. Well, there's a long process, but you feed E. coli plastic, it eventually produces Tylenol. What is left over from that process? I mean, you know, usually chemistry and biology aren't 100% efficient.

Here Dr. Wallace monitors the growth of the bacteria. He’ll eventually feed the bacteria a soup of broken down PET plastic, a common form of plastic used in bottles and food packaging. (Photo: The University of Edinburgh)

WALLACE: Yeah, exactly. So first of all, we have to take the plastic. And we took a waste plastic bottle, in this example, just one that we that we found on the streets on the way to lab one morning, and we deconstruct that or depolymerize that using established chemical methods, which basically take the polymer and release its chemical monomers, or the building blocks of that polymer. And those building blocks for polyethylene terephthalate, or PET plastic, which is the plastic we focused the study on, is two molecules. The first is called terephthalic acids, and the second is called ethylene glycol. And there are very many different uses for ethylene glycol in the industry. And we focus, in this instance, on the use of terephthalic acid, that other monomer that comes from deconstructed plastic. So it creates sort of like a plastic soup, if you like, which we then feed to the bacterium. And they take one part of that and transform that into Tylenol, but they leave that ethylene glycol alone. So that is one of the other things that comes from the process that can be used in other sort of industrial situations.

DOERING: And by the way, you mentioned this like P-E-T, PET plastic. What kind of plastic is that?

WALLACE: So PET is probably one of the most widespread plastics that's used throughout modern day society. It's a very rigid, very durable synthetic material that's used to make things like plastic bottles or sort of the films you get on top of salads and sandwiches and in the supermarkets. It's designed to be very robust, but because of that reason, when it's either sent to a landfill or it's unfortunately sometimes ends up in the environment or in the ocean, it's very resistant to degradation, and that's what causes it to accumulate and causes all those pollution issues that we widely associate with the plastic waste crisis currently.

DOERING: So let's zoom out to the bigger picture. A lot of pharmaceuticals actually come from fossil fuels, which is part of why this process is even possible. But just how much of our medicine comes from fossil fuels?

WALLACE: Yeah, this is something that absolutely fascinates me, and has been a really interesting point that's come from this research. I think just it really astounds me as a scientist, that people don't realize that the majority of the medication they take every day comes from fossil fuels. It's a refined petrochemical. It's the exact same material that you put in your car. I think it's 60 to 70% of all of the medication that we rely on to treat disease currently are reliant on this natural feedstock, fossil fuels. And the real issue with that is two things. The first is fossil fuels are not a limitless resource from which we can make these medications from. In fact, they're running out at quite an alarming rate, and the industrial processes that we use to transform fossil fuels into modern day medications are hugely polluting into the environment. So by taking this technology and programming bacteria to do this in a much more sort of milder, much greener way, much more eco friendly way, we not only defossilize the manufacture of this worldwide essential medication in a way that doesn't damage the environment or release climate emissions, but we also clean up plastic waste from the environment at the same time.

DOERING: By the way, why use biology and not just chemistry to do this?

Though the process isn’t nearly ready for an industrial scale production, Dr. Wallace hopes that in the future consumers will have the opportunity to buy acetaminophen not derived from fossil fuels but rather from plastic waste. (Photo: The University of Edinburgh)

WALLACE: Yeah, that's a really interesting question, actually. Certainly, to depolymerize plastic, you can use chemistry to do that. You can also use biology, but typically, bio-based processes operate at very low temperatures. They operate in very sort of mild water-based reactions. Whereas chemical methods, you typically need much more energy input to heat these reactions up. They tend to use, you know, petrochemical based solvents as well, to try and help these reactions go faster, and catalysts as well. So I think the bio-based processes are on the whole a lot milder and use a lot less energy, and are better for the environment themselves. But to make paracetamol from or Tylenol from plastic bottles, you cannot do that. It's impossible using chemistry alone, and it has to be done using biology.

DOERING: And by the way, paracetamol is just a different name for acetaminophen, or Tylenol. Is that right?

WALLACE: Yeah, of course. Sorry, it's my Britishism. That's absolutely the brand's name that which we sell acetaminophen under. It's the same as Tylenol. Absolutely.

DOERING: I'm going to play devil's advocate for a second. This research isn't nearly advanced enough to be scaled up anytime soon. So you know, how optimistic should we be that one day, most of our acetaminophen, our Tylenol, comes from plastic bottles?

WALLACE: Yeah, that's a really great question, actually. And I think it's really important to emphasize, we're an academic discovery lab. This is a very early stage project, a very early discovery proof of concept project that has shown that this is actually feasible. The next steps for this is absolutely to try and see whether we can scale this up to make really large quantities of paracetamol from existing plastic waste. And we're working with industry, both in the UK and the world around the world now to try and see whether this could be commercially feasible in the future.

DOERING: So, what's next for you as a researcher?

WALLACE: Yeah, this, this project has been wonderful, and it's been a real labor of love for many, many years up to this point, but it really does feel like the starting point for both this and the wider field of engineering biology. Because, you know, if we can program bacteria using this technology to turn plastic waste into Tylenol, imagine what else we can do, right? But more broadly than that, waste is just carbon, and microbes love carbon, so we've been examining all different types of weird and wonderful wastes and thinking, okay, you know, how can we program biology to turn this into something that's a bit more exciting than simply landfill or waste that goes to incineration? We published a piece of work a couple of months ago where we examined fatberg waste from the sewers in London. And these are sort of greasy deposits that block the sewers underground. And we did a chemical analysis of these, and it turns out they're really rich in organic small molecules, so tons and tons of carbon, literally. So we designed some bacteria that could eat these fatbergs from the sewers and turn them into fragrance compounds that you could wear. And we're currently working with a Swiss fragrance manufacturer to try and see whether we can take sewer waste and turn them into fragrances that you will buy potentially in the future. So this idea of waste is just carbon and biology can be engineered to turn that into a whole variety of different products. It really does feel like this is the sort of creative beginning of something really quite exciting.

The vast majority of our waste is simply carbon molecules. And since microorganisms love carbon, Dr. Wallace envisions a future where we could use microbes to turn a whole range of wastes into new products rather than relying on our dwindling fossil fuel reserves. (Photo: The University of Edinburgh)

DOERING: Wow. My head is spinning at the transformation that, that, that is quite some upcycling there of fatberg waste to perfume.

WALLACE: Yeah, exactly. So would you, would you wear perfume that came from fatberg waste?

DOERING: I'd have to smell it first. But hey, it's, it's just carbon, right?

WALLACE: It's just carbon. Exactly. If we can wear perfume that comes from oil, or if we can take medicine that comes from oil, why not from fatbergs? Why not from plastic bottles? Absolutely.

DOERING: Stephen Wallace is the lead author on the paper and a Professor of chemical biotechnology at the University of Edinburgh in the UK. Thank you so much, Dr. Wallace.

WALLACE: Thank you, Jenni, it's been a pleasure to be here. Thanks.

Related links:

- Read Dr. Stephen Wallace’s original study

- Learn more about Professor Wallace

- Discover other surprising products made from fossil fuels

[MUSIC: Lifelike, “Nightwalk” on Nightwalk EP, Anjunadeep]

BELTRAN: After the break, The US Forest Service wants to take a U-turn from the “Roadless Rule.” That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Pinetop Perkins, “Careless Love” on Ladies Man, by Leadbetter, M.C. Records]

Birdnote®: Poisonous Birds

A hooded pitohui perches on a human hand. (Photo: Benjamin Freeman, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BLETRAN: Before the break we heard about a biotech breakthrough using bacteria and a gene from mushrooms to turn plastic into a painkiller. It’s very impressive and novel, but of course, nature herself has been tinkering with biology and chemistry for as long as life has existed on this planet. And some species have evolved to make use of special chemical weapons – a.k.a., venom or poison. Here’s BirdNote’s Michael Stein with more.

BirdNote®

Poisonous Birds

Written by Conor Gearin

STEIN: The world is full of poisonous creatures. Some butterflies, beetles and frogs use bright colors to warn birds and other predators that they’re full of toxins. But you might be surprised to learn that some birds are poisonous, too.

[Hooded Pitohui song]

The Hooded Pitohui is a bird that lives in New Guinea and eats a toxic beetle. The pitohuis aren’t sensitive to the beetle’s toxin, so they can accumulate large amounts of it in their skin and feathers. Scientists examined the chemicals from pitohui feathers and identified the same type of toxin found in poison-dart frogs. Like the birds, the frogs may also gain their chemical defenses from eating insects. But pitohuis aren’t the only birds that pack a toxic punch. When Ruffed Grouse eat a plant called mountain laurel, they pick up a poisonous compound that can make them an unappetizing meal for a fox or a human hunter.

A ruffed grouse can become poisonous after eating mountain laurel. (Photo: Noah Poropat, iNaturalist, CC BY 4.0)

[Ruffed Grouse calls]

And quail in the Eastern Hemisphere sometimes snack on hemlock, turning them into a very upsetting dinner item.

[Common Quail calls]

Many predators like to eat birds, making the world a pretty dangerous place for them. But evolution has made some birds a little dangerous, too.

[Hooded Pitohui song]

I’m Michael Stein.

###

Senior Producer: Mark Bramhill

Producer: Sam Johnson

Managing Editor: Jazzi Johnson

Content Director: Jonese Franklin

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Ruffed Grouse ML 446222541 recorded by Andrew Spencer, and Common Quail ML 354955891 recorded by Hans Norelius.

Hooded Pitohui Xeno Canto 750410 recorded by Iain Woxvold.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2023 BirdNote March 2023/2025

Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# poison-01-2023-03-14 poison-01

Reference:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25839151/

https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/4037/Dumbacher1992.pdf…;

https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/did-you-know/pitohui-bird-contains-de…

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13181-022-00891-6

BELTRAN: For pictures, migrate on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related link:

Find this story on the BirdNote ® website

[MUSIC: Time for Three with with Jake Shimabukuro, “Happy Day” on Time for Three, by N. Kendall/arr.Bob Moose, Universal]

DOERING: We are inviting you, our listeners, to join us September 17th and 18th for Bridging Communities with Hope: An Environmental Justice Conference for All.

This free two-day conference at the UMass Boston campus brings together leading voices of the environmental justice movement and grassroots leaders from across the country.

BELTRAN: The Center for Climate and Environmental Justice Media is hosting the event in collaboration with the UMass School for the Environment and Living on Earth.

We hope you can join us in person. Did we mention there will be free food?

But if you’re not in the Boston area, don’t worry, there will be a livestream you can join.

DOERING: So, don’t miss this important forum for environmental justice on September 17th and 18th. To register for free, visit loe.org/events.

[MUSIC: Time for Three with with Jake Shimabukuro, “Happy Day” on Time for Three, by N. Kendall/arr.Bob Moose, Universal]

Roadless Rule Under Fire

A roadless area in the Tobacco Root Mountain Range, in Deerlodge National Forest, in Montana. While national forests are definitionally opened up to logging, roadless rule areas often overlap with crucial old growth habitat. (Photo: Preston Keres, USDA, Courtesy of the Center for Biological Diversity)

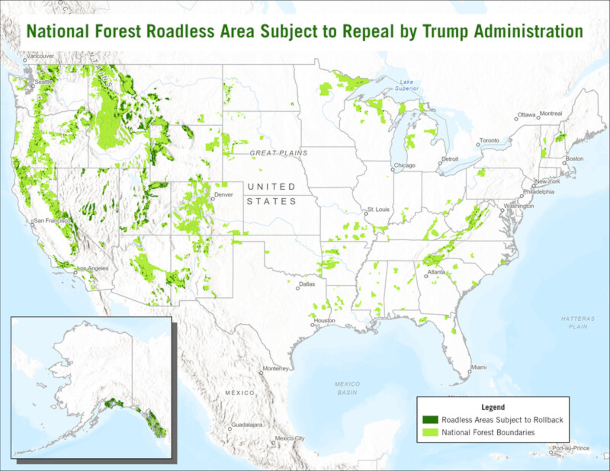

DOERING: Some of the wildest places in the United States are not officially wilderness. Instead, they are part of the national forests, managed by the US Department of Agriculture because trees are in one sense a “crop” to be grown and harvested. But forests serve many purposes besides just being a source of timber, and a key policy called the “Roadless Rule” has for decades recognized the importance of keeping some national forest land free from logging and from the roads that come with it. Now, the Trump administration is looking to repeal this rule, which currently protects over 45 million acres of national forests from road development. The USDA announcement claims roads are needed to help fight and prevent worsening wildfires, without mentioning that climate change is fueling the drought and heat conditions that lead to them. And research suggests more roads may in fact spark more wildfires. Here to discuss the implications of repealing the roadless rule is Randi Spivak, the public lands policy director for the Center for Biological Diversity. Welcome to the show, Randi!

SPIVAK: Thanks for having me.

DOERING: So, what is the Roadless Rule exactly, and what areas of the country does it protect?

SPIVAK: So the Roadless Area Conservation Rule, or Roadless Rule for short, it's a landmark conservation policy that's protected our last intact wild forests for more than two decades, and the rule generally prohibits road building and logging in our last unfragmented, undeveloped forest in our National Forest System. So there are roadless areas in 39 states across the country. Taking a step back, you know, why this rule got created in the first place? So, our National Forest System across the country, from the East Coast and West Coast and north, south. You know, there's over 100 national forests in this country, most of it has been opened up to heavy logging and heavy roading. The roadless areas that we're talking about here, these are the last places. They were generally harder to get to. They're not the low elevation forest that could be logged most easily, and the Forest Service had built so many roads, we've got over 180,000 miles of roads crisscrossing our national forests, and that is more than twice the miles of roads in an entire transportation sector in the country. Roads are extremely damaging to forests and habitat and water quality, and so there was this movement basically to protect the last remaining roadless areas. Most of them are wilderness quality. It takes Congress to designate an area as wilderness. This rule was done administratively in recognition of how important these roadless areas are ecologically, to clean water and to wildlife habitat. And frankly, the Forest Service has built more roads than they can even maintain.

A map depicting the National Forest Roadless Areas that are subject to repeal by the Trump administration. (Photo: Kara Clauser, Center for Biological Diversity)

DOERING: So we're talking to you because the USDA announced that they intend to repeal the Roadless Rule, and they've opened up a 21-day comment period, up until September 19. How does this timeline compare to previous attempts by the federal government to repeal administrative rules?

SPIVAK: It's pretty short. Twenty-one days, I think that might be a record. Usually those comment periods are 60 days. And just to be clear, there'll be two phases where the public can weigh in. This first phase is called scoping. That the deadline is September 19, and that's when the administration put out their intent to repeal the rule. And they're asking people, what issues should we analyze in the more formal proposal? We'll see that proposal probably based on what the USDA is saying, sometime the winter 2026, Jan-Feb. And we don't know how long that comment period will be. In the past they've been 90 days. I imagine it's going to be much shorter.

DOERING: Tell me about how public comments really played into when this rule was first created.

SPIVAK: Yeah, so this rule was first created in 2001 although there was a lot of momentum building to make this rule happen for decades, just so early on in that comment period, there were hundreds of meetings across the country. Of course, we didn't have the internet then. There were about 600 meetings across the country. Over one and a half million people weighed in in support of the Roadless Rule. That was the most comments ever at that time for a conservation measure. And I think it was a six-month comment period. Overwhelmingly, people were in support of protecting our last remaining wild forests, and they supported the Roadless Rule, overwhelmingly.

DOERING: So this is about roads in national forests. Some would say the national forests are there to be logged. You know, we have other places that are set aside for wilderness, for recreation. What's your response?

Jocelyn Dodge, a U.S. Forest Service Recreation Forester, watches the sunrise over the Whitetail Mountains in Butte, Montana. Roadless areas do not prevent human recreation in national forests. (Photo: Preston Keres, USDA, Courtesy of the Center for Biological Diversity)

SPIVAK: Well, the law that governs the national forests, yes, it does allow logging. It doesn't say how much logging, but it also mandates that our national forests provide viable wildlife populations and also protect clean drinking water and watersheds. So they have to cover all those bases. And right now, our national forests have been heavily logged. They are heavily eroded. There are over 500 threatened and endangered species on our national forests, in large measure, because they have been logging and roaded. And therefore protecting our last wilderness areas, as well as congressionally designated wilderness areas, are really important to make sure that the law upholds its promise to protect watersheds and clean drinking water as well as species habitat.

DOERING: And when it comes to habitat, fragmentation is one of the biggest problems for species. So I can imagine that, you know, keeping the roads out of places that aren't already covered in roads could be really helpful for some of these species that are struggling.

SPIVAK: Yeah, that's right. So thinking about roads, here's why roads are an issue. So first, they're the largest source of sedimentation entering our mountain streams. Think about when you bulldoze a road into a steep hillside, the rain and snow causes tremendous amount of erosion that sends a lot of sediment and pollution into streams. So if you think about, let's say, fish, steelhead trout, salmon, they need cold, clear waters for fishing. When you've got chronic sedimentation pouring into streams, that warms the temperature, it actually covers the fish eggs, it really harms fish spawning. It's also important to understand that national forests, they're the headwaters of most of our great rivers and streams in this country, and they're the largest source of U.S. municipal water supplies. In fact, over 60 million people get their drinking water from national forests and in over 33 states. And roadless areas, they protect headwaters from roads in many, many of these headwater areas. So keeping these areas roadless is also important for maintaining clean drinking water.

Roadless areas can also be an important part of maintaining clean sources of drinking water. (Photo: Ted Zukoski, Courtesy of the Center for Biological Diversity)

DOERING: Randi, could you give us an example of one of these species that is protected by this Roadless Rule?

SPIVAK: Sure, as I mentioned, there are hundreds of threatened, endangered species and even many more common species that spend time in roadless areas. It's everything from butterflies and salamanders and native salmon and cutthroat trout and grizzly bears. And we'll talk about grizzly bears for a minute, because they're super important in the Rocky Mountains and Alaska and elsewhere. You know, they do not like human presence, and roads bring human presence, and so they avoid those areas, and it really interferes with their breeding and their hibernation. And so grizzly bears are one example of a species that really needs sort of refuges, protected cover, away from roaded areas and human presence.

DOERING: And by the way, what's the relationship of old growth forest with roadless areas?

SPIVAK: There's a heavy overlap of old growth with roadless areas. The Tongass has the most acres of roadless areas in the country, and also probably the most old growth forests. And old growth forests are not only beautiful, super important for many species of wildlife, but they also store enormous amounts of carbon, and they continue to pull carbon from the air. And logging basically emits about 90% of the carbon that's stored in trees, and then you never get that sequestration again. Small, young trees do not do the job of large, old, standing trees.

Grizzly bears are one species that are placed at risk with a potential rollback of the country’s roadless rule. (Photo: Terry Tollefsbol, NPS, Courtesy of the Center for Biological Diversity)

DOERING: Randi, the Trump administration claims that repealing this rule will actually help us fight forest fires. What do you make of this idea?

SPIVAK: Roads actually increase human caused wildfires. There were research studies that show that wildfires are four times more likely in areas with roads than in roadless forest tracks, and that's because roads allow human access. Think of it. It's a dry, hot summer day. There's a spark from a tire. Somebody carelessly throws a cigarette butt out the window, or unattended campfires. So the science unequivocally shows that where there are roads, there will be more fire ignitions. And there's another study that showed more than 90% of all US wildfires happen within half a mile of a road, and again, they're caused, unfortunately, by humans, unintentionally. So no, in this case, more roads will equal more wildfires.

DOERING: Why is the administration trying to repeal this rule?

SPIVAK: You know, Trump's agenda writ large, he is looking to get rid of regulations that protect our water, our air, our land, our wildlife, and against climate change. He's doing this across the board. He has issued an executive order that calls for significantly ramping up logging on our national forests, and I'll quote, “to exploit our timber resources.” You know, this is... he's got drill, baby, drill. This is just another log, baby, log. I mean, Trump really just sees the natural resources in this country as places to exploit. Look, once you open up these areas to roads and logging, and you bulldoze roads in and start logging them, these areas are lost forever. They will forever be industrialized. We need to keep our roadless forests roadless for now and future generations.

DOERING: And to what extent is there any legislation in Congress about this?

Tongass National Forest contains roughly 40 percent of the carbon stored by the entire U.S. National Forest system. As it is one of the last remaining intact temperate rainforests in the world, conservationists worry that logging roads will degrade Tongass' 17 million acres of forest space. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

SPIVAK: There is a bill, the Roadless Area Conservation Act of 2025 and they are looking for cosponsors now, and that bill would make the Roadless Area Conservation Rule permanent.

DOERING: Randi Spivak is the public lands policy director for the Center for Biological Diversity. Thank you so much, Randi.

SPIVAK: Thanks for having me.

DOERING: Public comments on the proposed repeal of the roadless rule are welcomed through September 19th. Find the link to the USDA press release and more on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Read the Center for Biological Diversity’s statement on the Roadless Rule repeal

- Comments on the roadless rule can be submitted here

[MUSIC: Guitar Dreamers, “Big Yellow Taxi – Instrumental” on Guitar Dreamers Cover Joni Mitchell (Intrumental) CC Entertainment]

BELTRAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth