June 27, 2025

Air Date: June 27, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

EPA Ignores Climate Dangers

View the page for this story

This June the US Environmental Protection Agency proposed eliminating regulations that limit climate changing gases from power plants, about a quarter of US emissions. Harvard Law Professor Richard Lazarus, an environmental and constitutional law scholar and author of The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court, speaks with Host Steve Curwood about the perils of the broader Trump administration effort to weaken federal environmental protections. (14:49)

From Plastic Trash to Art

View the page for this story

The ugly truth of plastic is that the world produces over 400 million metric tons each year and recycles less than ten percent of it. But artist Erik Jon Olson is transforming unsightly plastic waste into beautiful, quilted works of art which are popping up in galleries and exhibitions across the United States. He joins Host Jenni Doering to share the meaning and method behind his whimsical and striking artwork. (13:30)

Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet

View the page for this story

In his recent book Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet, Tony Juniper explores how tackling economic inequality within and between countries will go far to solve the climate and biodiversity crises. Tony Juniper is a former head of Friends of the Earth UK, has long advised King Charles III on the environment and climate and now chairs Natural England, a government conservation agency. He joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the transformation that’s urgently needed to allow planet and people to thrive. (16:47)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250627 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Tony Juniper, Richard Lazarus, Erik Jon Olson

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

And I’m Jenni Doering.

The US Environmental Protection Agency moves to unravel power plant regulations.

LAZARUS: It’s astounding, what the Trump administration has done. They’re trying to eliminate the EPA bureaucracy. If they succeed, that’ll make it very hard three years from now to put Humpty Dumpty back together again. That’s my biggest worry.

CURWOOD: Also, reframing our relationship with the natural world and each other.

JUNIPER: It’s that indigenous worldview that offers us the prospect for salvation. Because the indigenous worldview is not about nature over people, it’s about nature and people, and looking after nature for the people. And that is something that we can still do, if we take action quickly enough.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

EPA Ignores Climate Dangers

Fossil fuel-fired power plants are one of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gasses in the United States. Above, a coal-fired plant in central Wyoming. (Photo: Greg Goebel, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Record summer heat is scorching the northern hemisphere around the world from Japan and China to Europe and North America. Blistering heat waves in the US have already smashed records from Minneapolis to Boston to Philly with “dangerous” heat index numbers. Records will likely keep getting broken as steadily increasing emissions of greenhouse gases continue to overheat the planet. But the Trump Administration’s Environmental Protection Agency no longer wants to use its authority to do something about the climate crisis. This June the EPA proposed eliminating regulations that limit climate changing gases from power plants, about a quarter of US emissions. Here to explain is Harvard Law Professor Richard Lazarus, an environmental and constitutional law scholar and author of The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court. Professor Lazarus, welcome back to Living on Earth!

LAZARUS: Wonderful to be here, Steve, always fun to join you in conversation.

CURWOOD: Great to have you here. So Professor, what was your initial reaction to the EPA's proposal to roll back rules for CO2-emitting power plants?

LAZARUS: Oh, I mean, obviously it's devastatingly sad, but it's no surprise, right? We have a president who campaigned on it, and we have an EPA administrator who, a few months ago, said that his goal was to basically put a dagger in the heart of climate change religion. So by the time this latest proposals came out, we were ready and steeled for it, but still in the greater arc of things, it's discouraging. Climate change is not going away, and every day we lose in addressing it makes it exponentially harder to do anything about it.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Now, this decision flies in the face of, I guess, what's called the endangerment finding by the EPA back in the day, which was based on a Supreme Court case called Massachusetts versus the Environmental Protection Agency. Please give us a brief overview of the case and the endangerment finding.

Richard Lazarus is the author of “The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court.” It takes a look at the landmark environmental case Massachusetts v. EPA, which decided that greenhouse gasses are air pollutants and therefore could be regulated under the Clean Air Act. (Photo: Courtesy of Richard Lazarus)

LAZARUS: So in Massachusetts versus EPA, the EPA, under the Bush administration, had declined to make an endangerment finding. They didn't say greenhouse gasses didn't endanger public health and welfare. They said, we're not going to decide that issue. What this us, Supreme Court did in Massachusetts, EPA is they first said, very importantly, for the first time ever, greenhouse gasses are air pollutants within the meaning of the Clean Air Act. That's actually the central holding of the case, because before that, their EPA had never regulated them. Under the Bush administration, they said they're not air pollutants. So for the first time that the Court said, "No, they are air pollutants, they come under the rubric of the statute." The next question the court answered was whether EPA was right in saying we're not going to decide whether they endanger public health and welfare. And the court said, "The reason you've given for not deciding, they're invalid," and they sent it back to EPA. They didn't tell EPA they had to find they endangered public health and welfare. They didn't even tell EPA, as part of a compromise from the court, that they had to make a finding. They simply said, "The reasons you gave weren't legally valid." So went back to EPA. The Bush administration did nothing. They sat on it. This is George W. Bush, but then during the Obama Administration, this what you alluded to before, the Obama Administration, December 2009 at the end of the first year, EPA took that big step. And they made a formal finding the emission of greenhouse gasses can be reasonably anticipated to endanger public health and welfare, and when that happens, that triggers all the arsenal of the Clean Air Act now for climate change.

CURWOOD: So what would it mean for the EPA to be successful in going back on such a historic decision?

LAZARUS: Well, if they were successful in making a finding upheld by the courts, the admission to greenhouse gasses cannot reasonably anticipated to endanger public health welfare. That would end regulation greenhouse gasses under the Clean Air Act. And the Clean Air Act is our only federal tool for regulating greenhouse gasses. So whether it's airplanes, cars, power plants, landfills, oil and gas exploration, all of which emit greenhouse gasses, all that Clean Air Act regulation would end simultaneously.

President Trump was unsuccessful in reversing Clean Air Act regulation of fossil fuels during his first term in 2016. While Lazarus was unphased by these initial threats, he says his concerns are growing after the EPA’s latest proposal. Above, Trump gives remarks at a 2017 Unleashing American Energy event. (Photo: Simon Edelman, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So from your perspective, as a lawyer, as a law professor, how likely is it that the Trump Administration's EPA will succeed in making such a reversal?

LAZARUS: Well, I will tell you, when I first heard they were contemplating this, they didn't do it in the first administration, my reaction was, make my day. In other words, try to challenge it, because you'll be wasting your time. I'll have to tell you, in a Trump 2.0, my thinking has evolved, and I'm more concerned. And let me explain why. The science hasn't changed at all. There's no question that greenhouse gas emissions endanger public health and welfare. The question is whether the Trump Administration can find some hook, some statutory hook, some technical error. The EPA, they'll allege made in making those findings and use it to unravel it. The science is no less clear. So let me tell you what they're doing, so far. They've made the announcement they're going after the endangerment finding, and I think they will, but they haven't done it yet. What they've done is something that leads up to it, and that is they've said we're no longer to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants, which is a major source of greenhouse gasses. And they haven't done it by saying they're going to withdraw the engagement funding. They've done it by saying to regulate those power plants, EPA must make a decision in the administrator's judgment that greenhouse gas emissions from power plants may be significantly contribute to air pollution that may reasonably anticipate endanger public health and welfare. So they're not going after the endangerment finding yet itself. They're saying it requires significant contribution, and here they're playing some games with precedent and language. So they're not really going after the science. They're going after what “significantly” means in the statute. They're trying to make this a question of law.

CURWOOD: And from your perspective, how successful will they be at picking this nit?

Former President Biden made significant moves towards advancing environmental justice during his presidency, Lazarus comments. Above, Biden signs the Executive Order “Revitalizing Our Nation’s Commitment to Environmental Justice for All” in April 2023. (Photo: Official White House Photo by Cameron Smith, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

LAZARUS: Well, I hope they're not successful. I'll tell you what the argument is and why I still worry. I wouldn't have worried eight, nine years ago. They're going to argue the word significantly is a word to which means it's got to be important, and a word which the administrator gets a lot of discretion in deciding whether it's met or not, and they're going to say it's not met because significance is a policy determination, and that allows the administrator to consider costs. And here, the administrator is going to decide that significant depends upon whether or not you can show that reducing greenhouse gas emissions by a certain percentage from power plants will affect climate change worldwide. And given how much emissions are worldwide, the power plants only consist of now 3.5% because they've gone down a lot, they say, look at such a small percentage, and you're not going to reduce it to zero. So we don't think that's significant. I think that argument should lose, clearly. Power plants are one of the largest sources in the United States that meets I think any fair definition as significant. But here's what worries me, Steve. I'm not worried about the DC Circuit. They'll hear the case first. I worry about the United States Supreme Court. In the last several years, in case after case after case, the United States Supreme Court has ruled against environmentalists in sweeping opinions. They don't seem to buy in to the importance of these laws and the things they've successfully done for the past 50 years. So I'm worried when I shouldn't have to be worried, but it makes me worried.

CURWOOD: So I mean, across the board, it sounds like the Trump administration is just trying to throw pretty much any regulation under the bus that they feel gets in the way of business. Or am I overstating?

Lee Zeldin was President Trump’s pick for EPA Administrator and has held the position since January 2025. Under Zeldin’s rule, the agency has committed to fulfilling Trump’s promise to “unleash American energy,” largely through deregulation of existing Obama and Biden-era legislation. (Photo: Environmental Protection Agency, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

LAZARUS: Unfortunately, you're not overstating it. It's astounding what the Trump Administration has done. Day one, Executive Order Unleashing America's Energy targeted all the climate change regulation. They're trying to eliminate not just existing regulations, like every single one, but they're doing more than that. Even more troubling than that, they're trying to eliminate the EPA bureaucracy, the career employees, the scientists, the engineers, the economists. They're the ones who write the regs. They're the ones who do the work, the political officials, the few that come in, whether it's Obama, Biden or Trump or Bush, they come and go. The career people who are the ones who are the real experts on this, and the biggest tragedy of the Trump administration is to try and destroy that expertise. If they succeed, that'll make it very harder three years from now, if there's a more favorable administration, to put Humpty, Dumpty back together again. That's my biggest worry.

CURWOOD: Now, they would argue that, look, all these rules and regulations get in the way of economic progress, that people need jobs, they need to make money, to support communities, and that they're there to make the change that the voters told them to make.

LAZARUS: Yeah, I mean, I know you're right. I know they'll make that argument. It really is not an argument that can hold up. The fact is, we've had these tough laws for 50 years, and our economy has not cratered. Our economy has boomed, and we've had both economic growth and environmental protection. And the United States, we now have a gazillion dollar pollution control industry. We have 1000s of jobs which depend upon these statutes. We have property values which depend upon these statutes. So at this point, it's completely backwards to say that climate change regulation is inconsistent with economic growth. It is necessary for economic growth, and if Trump's policies prevail, our economy will pay the price for it.

Lazarus’s latest book, the second edition of “The Making of Environmental Law,” discusses the emergence of environmental law in the United States, its evolution, and the unique challenges it faces today. (Photo: Courtesy of Richard Lazarus)

CURWOOD: By the way, many of the Biden-era regulations for the environment were designed to advance environmental justice. What do you make of the Trump Administration and its efforts to cut funding from EJ programs and close such offices altogether? How does this proposal fit in the bigger picture?

LAZARUS: Well, it's tragically sad. Environmental justice is very simple. It's simply saying, "Put your resources where the problems are greatest." And that historically, we hadn't done that. Historically, government, including EPA, even when well-meaning, they had not paid adequate attention to the fact that pollution tends to go to the places least able to resist the powerful economic forces which are looking for the path of least resistance. And they were time and time again, poor communities in the country and communities of color. There's a racial dimension to this, too. And the lesson of environmental justice was, unless you actually proactively look for that possibility, you're going to repeat it on and on. So the Biden Administration, more than any other, knew that, and they said, "We're going to target those areas." It's actually figuring out where the biggest problems are, where the least enforcement is happening, where the standards are being ignored, and making sure they receive their fair share of a broader regulation. Make sure they receive their fair share of the resources needed to address the climate problems happening right now. It was an entirely sensible approach and the best we had ever done. And it's really a tragedy to have them go after it as well.

CURWOOD: You're a professor at Harvard Law School, and you're tasked with educating the next generation of environmental lawyers, but what's going on right now is certainly unprecedented. What are you telling your students as they head into this uncertain future?

Richard Lazarus is the Charles Stebbins Fairchild Professor of Law at Harvard University, where he specializes in teaching environmental law. (Photo: Courtesy of Richard Lazarus)

LAZARUS: It's a great question. I'll tell you, there's a lot for someone like me who's devoted my life to these issues to be discouraged about right now, to see so much successful environmental law be unraveled for irrational reasons. The one joy I get these days are these students. They are what gives me hope, because they're in my classrooms. They're ambitious. They want good things. They want to change the world, want to address climate issues and other issues which are really important. They come here, and they're smart. And more important to me than smart — smarts are a dime a dozen — they're hard workers. And basically what I tell them these days is the following: This is your time. Pick yourself up. You may be very discouraged by things, but this is your time. Pick yourself up and get to work. You wanted to make a difference on enviornmental issues? You wanted to make a difference on climate change? Well, guess what? We need you. The country and the world needs you now more than ever. This is not the time to sit back and be despondent. This is a time to work hard because we need you. You didn't get the benefit of being able to be passive and say, I'll sit back and enjoy the environment and take hikes. If you want to make a difference, you've got to work hard, you've got to be focused, you have to be strategic, and you have to be strong and steely and resilient, because a lot of political forces are going to be working against you. And they're hopeful. I think their time horizon a little bit different than mine because they're pretty young. They've got about, you know, 50 years on me. They're more likely to see Trump on what he's doing, as something, yeah, they'll live past it and they'll be ready to go.

CURWOOD: Harvard Law professor Richard Lazarus is the author of The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court. Thanks so much for taking the time with us.

LAZARUS: Thank you, Steve, always a pleasure.

Related links:

- Environmental Protection Agency | “Greenhouse Gas Standards and Guidelines for Fossil Fuel-Fired Power Plants”

- Read Richard Lazarus’ Harvard faculty page

- Learn More About the Rule of Five

- Living on Earth | "Court Catalyzes Climate Action"

- Living on Earth | The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court

[MUSIC: Luke Peixoto, “Synchronized Chaos” single, Groove Punch Studios]

DOERING: Just ahead, Whimsical and brightly colored art made from plastic trash. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Fame Gang, “Soulful Strut” on Solid Gold From Muscle Shoals (Expanded Edition), Capitol Records]

From Plastic Trash to Art

Erik Jon Olson makes decorative quilts out of single use plastic. Now Streaming, 2025, quilted plastic waste, 45"x85". (Photo: Courtesy of Erik Jon Olson)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Over 400 million metric tons of plastic are produced worldwide each year, leaving a huge carbon footprint and a waste problem that never seems to go away. Less than ten percent ends up recycled, leaving much of the rest to pollute our planet’s oceans, rivers, lakes, and land and break down into microplastics that are found nearly everywhere, from Mount Everest to the depths of the Mariana Trench, to our own bodies. But art can elevate plastic from trash to treasure. Minnesota artist Erik Jon Olson is transforming polymers into works of art which are popping up in galleries and exhibitions across the United States. And he joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Erik!

OLSON: Thank you.

DOERING: So I have to say, I was kind of floored by how beautiful your artworks are, and yet they're made of plastic. So can you please describe this metamorphosis and paint a picture for us of your art?

OLSON: Well, my art is quilted plastic waste. It is used plastic like what you would get frozen vegetables in, that kind of packaging. There's about 8 to 12 layers of plastic to get it to be thick and pillowed like an actual quilt would be. So it's a lot more layers than a quilt is. And I'll pin it in place, and then just start running it through the sewing machine, and then I will cut the shapes out of that quilted piece, bind the edges, and then I will sew those pieces together.

DOERING: Wow, not your grandmother's sewing project,

OLSON: No, but it is my grandmother's sewing machine.

DOERING: Oh, I love that.

OLSON: I do too.

DOERING: So what does it look like? What would somebody first notice, do you think, if they walked into an art gallery and saw one of your pieces?

OLSON: They would probably notice the bright color. That would be the first thing they notice. The color is from the plastic. I don't add any color to it. They would notice that they are very playful and that they're very whimsical looking. They would notice that they have a strong graphic design quality to them. That is my creative background from advertising industry in graphics and graphic design, so that has a strong influence on what the designs look like. They'd also notice that they are rather large, like five by seven. So that's 35 square feet.

DOERING: Could you describe a favorite piece of yours? I know it's hard to choose, but if you had to.

OLSON: If I had to, it's called "Now Streaming." It's like a school of fish swimming in a pattern that is like an infinity symbol, and behind that stream of fish is like a hugely magnified blood vessel with big red circles in it. And then over the front of it is kind of like a net. And then in the background, that "S" curve of the blood vessel, when that shape is interacting with the infinity symbol shape, it looks like a double helix.

DOERING: Whoa, so like our DNA?

OLSON: Yeah. So what it is representing is plastic going into the oceans, breaking down into the microplastics that the fish eat. We eat the fish. The microplastics become nanoplastics and end up in our bloodstream. And pretty soon, if it hasn't already, it's going to end up in our DNA.

Pictured above is Surged, 2024, quilted plastic waste, 55"x68". (Photo: Courtesy of Erik Jon Olson)

DOERING: Yeah, they end up in our bloodstream, and they seem to be wreaking a lot of havoc in our bodies.

OLSON: Yes.

DOERING: Yeah, I mean, I really appreciate how accessible some of your artwork is. Like, you know, this green one that you have that's made of recycling motifs. It has the numbers one through seven, all jumbled up. That's one through seven for the types of plastic. And I mean, I love the irony of that, since this is made of plastic, and the fact that you're like, really getting the message across about this like morass that is recycling symbols.

OLSON: Yes, and the title of that piece is, "Not So Green As You Think."

DOERING: Ah.

OLSON: And that's my statement on how deceptive that recycling campaign really is.

DOERING: Yes. It makes us think, oh, wonderful, this is recycled.

OLSON: You think they're all getting recycled because they all have the chasing arrow. So they're all getting recycled. It's like, no.

Not So Green as You Think, 2024, quilted plastic waste, 50"x42". (Photo: Courtesy of Erik Jon Olson)

DOERING: Tell me a little bit about how you became an artist. What drew you to this medium?

OLSON: Oh, around 2005 I left the advertising industry. One day I came home and I said to my wife, I just can't do this one more day. I just can't do it. At the same time that I was going through that, a very good friend of mine had become really concerned about the amount of single use plastic in the waste stream, and he figured out that you could layer it up and run it through a sewing machine. So he started a small cottage industry company that made functional items out of that sewn up plastic, like computer covers or tote bags. And knowing my advertising background, he conscripted me to do the branding of that company. But any manufacturing has waste. That process had waste too. He knew that I liked to make things out of whatever stuff was lying around. I've done that my whole life. So he convinced me to take the scraps of that process home to see what I could do with it. And then that's how I started working in this medium.

DOERING: What was it like to play around with this plastic when your friend sent you home with some, and what was it like when you made the first thing?

Erik’s quilted pieces can be quite large, spanning as much as 35 square feet. Exhibit installation, Post-Consumer, August – October 2023. (Photo: Courtesy of Erik Jon Olson)

OLSON: Oh, it was a long learning curve. So there was a lot of experimenting, and it took about three years before it popped into my head that maybe I should be adding some content to these pieces, and maybe the content should be about plastic, since I'm using plastic waste as the medium. If the content also was about the consequences of that plastic waste, then I would really punch home, I guess, that the actual medium becomes the message.

DOERING: How have you been influenced by other artists? And you know, who are you inspired by?

OLSON: An artist that influenced me from the very beginning, his name is Edward Burtynsky. He's a photographer from Canada. He'll fly a drone over a delta in Southeast Asia where all the junk is just going right into the ocean, or he'll have a drone shot over a strip mine. He's got this cool one that's just piles and piles, the whole thing is filled with used tires. It's just piles and piles of used tires. So it makes this really cool pattern and texture that you don't immediately connect, oh, it's tires. They're stunningly beautiful, and that beauty draws you in, and then after you're hooked in with that beauty, then you're like, slapped in the face with the ghastly message of what it is. So that's what I try to do with my artwork, although I'm relying on, more on playfulness and whimsy than stunning beauty.

California Dreamin', 2024, quilted plastic waste, 54"x54”. (Photo: Courtesy of Erik Jon Olson)

DOERING: Yeah, kind of a twisted beauty, I guess.

OLSON: Yeah, yeah.

DOERING: So Erik, you had a career in advertising before you retired and wound up becoming an artist. To what extent did that background inform the way that you approach your art now?

OLSON: Other than feeling like I have to make amends for trying to get people to buy crap they don't need. Well, a lot is the creative process that I go through is very much like I learned when I was in the advertising industry. So I don't like just sit down and start experimenting and putting stuff together and organically following where that's going. It's very much decided before anything happens, like from the news or from, well, from your program.

DOERING: Oh, really?

OLSON: Ideas start.

DOERING: Wow, we're coming full circle here.

OLSON: Yeah.

Erik says that he now has a zero waste artistic process. He incorporates every scrap he creates back into his pieces. (Photo: Courtesy of Erik Jon Olson)

DOERING: That's amazing.

OLSON: But once I have that visual that goes with the concept, then I start in sewing the plastic together and cutting away and...

DOERING: And by the way, where do you get your materials from? I mean, are you still getting them from your friend?

OLSON: Not anymore. I have now collected enough plastic from my own consumption that that's all I use now, so none of my plastic gets thrown away. I try to invent ways to put it back into my artwork. So over this last year, I was actually able to come to absolute zero material waste.

DOERING: Whoa.

OLSON: Yeah, that's cool.

DOERING: So I'm sure your art is always evolving, and it, you know, it's changed a lot over the last 20 years or so. What's next for you?

OLSON: Well, I'm going to keep going with this. Most of my art has been two dimensional, but with some of the ways I'm using all those little, tiny bits of scrap I'm moving or trying to move into some three-dimensional work, it is a real challenge for me, because my whole life has been spent in two-dimension world.

DOERING: So how are you doing that? Does that involve some paper mache, or, I don't know?

OLSON: No, it involves a lot of using a lot of the scrap as stuffing.

DOERING: Ah, okay.

Waste Knot, 2025, the waste from previous works, 42"x13"x7". (Photo: Courtesy of Erik Jon Olson)

OLSON: Like the latest 3D one, I made a clear plastic casing like a rope sausage, maybe three inches in diameter and about 14 feet long. And I had saved up all the clippings, and I stuffed that casing with all those tiny bits and pieces, and you can see them because the casing is clear, sealed the ends and then tied that big long rope sausage into a bow hitch knot, which is the knot that sailors typically use to tie the anchor to their boat. And it's, it is called, "Waste Knot," K-N-O-T.

DOERING: Why did you choose that knot in particular?

OLSON: Oh, because it was typically used as an anchor. And we are weighed down with our, with our plastic. And I was being weighed down because I didn't want to throw all that stuff out. So I was being weighed down by the idea of, how do I use the very last scrap, waste of the waste of the waste of the waste.

DOERING: Yeah. So, Erik, how do you feel about the climate moment right now, this like plastic catastrophe, a lot of these things that you cover in your work? What motivates you to keep on keeping on?

OLSON: Keep on, what motivates me? I do believe my anxiety motivates me a great deal over what's going on. Another thing that motivates me is how rapidly concepts keep coming to me. I can't turn it off.

Erik Jon Olson is an artist based in Minnesota. His work has been exhibited across the United States. (Photo: Courtesy of Erik Jon Olson)

DOERING: Wow, it sounds like you're kind of a conduit, receiving these ideas from the universe or something.

OLSON: That’s what it feels like, yeah, yeah.

DOERING: You know, there's all kinds of different ways to grapple with and respond to the climate crisis. I mean, I'm grateful for all the scientists who are trying to understand what's happening, but why do you think we need artists in this moment?

OLSON: I firmly believe that art can change things for the better. I was just listening to and watching a little video that was talking about how in cities that have areas that are not cared for, and the crime rate goes up, and then people start feeling hopeless, and things just get worse and worse. But if the city invests in, say, making that empty lot, if they make it green, paint a big, beautiful mural on the building that's sitting next to it, when those spaces are made into artful spaces, the crime rate goes down. So it does give people hope, I think, and it lifts, it lifts up the human spirit.

DOERING: Erik Jon Olson is an artist based in Minnesota. Thank you so much for joining us. This has really been a pleasure.

OLSON: Absolutely.

DOERING: And you can find pictures of Eric's artwork on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Learn more about Erik Jon Olson

- Learn more about Edward Burtynsky

[MUSIC: Vulfmon “Valk” single, Vulf Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, more fairness as a solution for the climate crisis. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility - who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Vulfmon “Valk” single, Vulf Records]

Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet

Tony Juniper’s newest book, Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet. (Photo: Courtesy of Bloomsbury)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

It’s no secret that the poorest people on earth bear the brunt of the climate crisis yet are the least responsible for it in the first place. And they are often faced with exposure to toxic pollution, lack of access to quality green space, as well as barriers to education and economic opportunities. In his recent book, Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet, Tony Juniper explores how tackling economic inequality within and between countries will go far to solve the climate and biodiversity crises. Tony Juniper is a former head of Friends of the Earth UK, has long advised King Charles III on the environment and climate and now chairs Natural England, a government conservation agency. Tony, welcome back to Living on Earth!

JUNIPER: It's so good to see you again Steve, it's been too long.

CURWOOD: Tony, a major part of your book points out that we're stuck in the environmental emergency because of income disparity, that our focus on economics, rather than the environment, leads us in a position where we have a lot of people who don't have so much money, and a few people that have a lot and that that's sort of the gordian knot to unwind the environmental crisis. Why is that so?

Tony Juniper at the World Economic Forum's Annual Meeting of the New Champions, also known as Summer Davos, which was held in Tianjin, People's Republic of China in 2016. (Photo: Jakob Polacsek, World Economic Forum Flickr, CC BY NC SA 2.0)

JUNIPER: Well, these wealth, these wealth disparities, and indeed, there are disparities that link to race as well, which you know, are really fundamental blockages to where we need to go. And so on the income inequalities, you know, we have a worsening level of inequality in the world. It started at the beginning of the 1980s and it's been getting progressively worse ever since, to the point today where a couple of thousand billionaires control more wealth than the entire 4 billion of poorest people in the world. What is the remedy to that? Well, one answer that is debated endlessly, and which is the priority of most governments is to achieve economic growth. Now there are many upsides from economic growth, but when much of the benefit is going to a tiny minority of already rich people, I think we do have to ask questions about the distribution of the wealth when it is poverty that is blocking the environmental challenges being met. And there's one statistic from the World Bank, which I thought was quite enlightening, it set out how between 1996 and 2021, so a 25 year period, of all the wealth created in the wild over that time, and it was a spectacular quantity of trillions of dollars of GDP, 38% of it went to the 1% of already most wealthy people. And if you look at the top 10% of people, then the disparity is greater still, and so we're running on a treadmill and we're not going forward in terms of leveling out these massive income disparities as we pursue more and more economic growth. It's getting worse, and yet that is the biggest problem we have in tackling global warming and the degradation of ecosystems and consumption of resources is because we're always trying to protect the interests of the least well off. That's one of the reasons why we continue on that treadmill, is because we see it as being of benefit to low-income people.

CURWOOD: Well, wait, let me just stop you right there. The environmental degradation you write about in your book, really hits low-income people harder than the rich folks.

JUNIPER: Yes, it does.

CURWOOD: So why would low-income people be opposed to dealing with the environmental crisis?

The Amazon is one of the worlds’ most biodiverse places on earth and it plays a crucial role in regulating the world’s and carbon cycles. (Photo: CIFOR, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

JUNIPER: They're not. Very often it's the elites who run governments who cite the least well off people as the reason why we shouldn't move to sustainable agriculture, because it will make food more expensive. You see that here in the British media quite a bit. We've been told for many decades that we didn't want to invest in upgrading our water treatment systems in this country because this would put up bills for poor people, and so our rivers now have high levels of sewage waste in them because we didn't invest, because we wanted to keep bills low. And at the moment, we have a renewed focus on the targets to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions in this country, with lots of opposition coming against targets for renewable energy because of the impact this will have on poorer consumers. And so the reasons why environmental policies are challenged often circle back onto the plight of least well off consumers when it is, as you say, Steve, those least well-off consumers who are suffering the worst consequences of environmental degradation in the first place, whether it be toxic pollution, the effects of climate change, or limited access to green space.

CURWOOD: So you write in your book, Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save The Planet, about income inequalities within nations, as well as among nations. Looking at the United States, what's our degree of economic inequality? And how do you think that affects how the US is addressing the climate and environmental emergency?

JUNIPER: Well, the United States is one of the countries that is extremely unequal. There are more unequal countries, but they're not at a level of advancement of the United States. And as I describe in the book, you know, there are many levels of how this manifests itself, in terms of the differences between the well off and the least well off. And in the United States, you know, there are very poor communities who suffer disproportionate impact from environmental degradation, and there is a rich literature formed from an environmental justice movement in the US that has set out in a great deal of detail with data revealing the extent to which it is nonwhite communities, Black and Hispanic communities, who suffer a hugely disproportionate level of toxic pollution. And also when it comes to some of the natural disasters, well less natural as time goes by, some of the disasters that accompany rapid global warming. I do talk a little about the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and how it was the Black communities in New Orleans who felt the brunt of that storm, and who were uniquely vulnerable in that part of the world because of where they lived and the lack of facilities they had and the extent to which they were exposed, just through their poverty, to a very unpleasant set of experiences that followed that storm. And so across the world, you see different manifestations of this and some of them, you know, they come back to us in the Western countries when it comes to the global dimensions of how you have very different experiences arising from environmental change.

Pictured above is the New York Stock exchange. In his book Just Earth, Tony Juniper argues that inequality is the main obstacle that blocks addressing climate change. (Dietmar Rabbish, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 4.0)

And I do actually cite the example of Afghanistan, a war in which both British and American troops, alongside many other coalition partners were involved, and I talk about that conflict from the point of view of a British Army General who gave me a briefing about his insights from two tours of duty in Afghanistan. And who told me about the extent to which that conflict was in large part fueled by the consequences of climate change, with very poor people living in rural areas unable to feed their families because of the way in which there was no water to sustain their crops, they had destitution that followed this then leading them to take money from the Taliban to join their forces and then to engage in that very bitter and ugly battle that went on for so many years, but which has its roots that general told me, in the consequences of global warming. And so this disparity in how the environmental consequences fall on different communities ,it's not only within nations it also can come back like a boomerang to hit us, even in countries where we feel quite secure and relatively well-off compared with some other countries.

CURWOOD: Tony, I know early in your career, you spent a fair amount of time in the forests of the planet, especially some of the tropical forests that are so important, and you say in your book that the percentage of people on the planet who are still indigenous is quite small compared to the amount of land and forests that they still are able to manage and protect. What are those numbers, and how are we doing with supporting them in keeping this protection going?

JUNIPER: So indigenous peoples constitute today a few percent of the global population and yet they manage at least half of the protected areas and the remaining biodiversity on the earth. And this is of material interest, because if you look at a map of the Amazon basin and where the remaining forests are, and then if you overlay that map of the remaining forests with where the indigenous territories are, where those people have control of the forests in Peru, in Colombia, and in Brazil, you see a very high correlation between the indigenous controlled lands and where the forest still remains, and this is a reflection of their worldview. So those people regard the forest as a living, spiritual entity. For Western derived cultures, the forest is a place where you can take timber from where you can mine iron and minerals and precious metals, including gold and it's a place where the forest can be cleared to make way for cattle pastures and for soya plantations. And the difference between an intact forest and a soya plantation at its most basic level, it is about the philosophical perspective of the people who are looking at the forest. One sees the forest as a market opportunity in the global economy. The other sees the forest as a sacred presence which needs to be handed on intact for the benefit of future generations, as well as the rest of life on Earth. So the role of the indigenous communities could not be more important at this emergency juncture in the history of humankind, when we can see now the effects of global warming taking on really quite troubling dimensions, and as we look into the specter of a mass extinction of animals and plants, it's that indigenous worldview that offers us the prospect for salvation, because the indigenous worldview is not about nature over people, it's about nature and people, and looking after nature for the people. And that is something that we can still do if we take action quickly enough, but we won't do it by continuing with our process of a quest for unending economic growth and expecting that to solve all of our problems, especially when most of that growth is going to a small proportion of already very wealthy people.

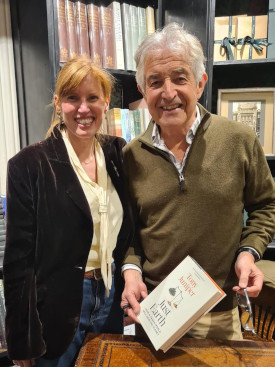

Tony Juniper (right) with Laura Fox (left), a Chronos Sustainability Specialist on Biodiversity and Agriculture. She worked with Tony Juniper on his new book Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet. (Photo: Courtesy of Tony Juniper)

CURWOOD: By the way, what is the income inequality among indigenous groups?

JUNIPER: Among indigenous groups, they tend to be very egalitarian and they tend to have a chief, but money is something which is relatively new to them and it will vary from community to community in terms of their continued cohesion as an indigenous society compared with those that have had more contact with the outside world, but they tend to be societies that work at a small scale and which thrive because people share things.

CURWOOD: Your book is basically optimistic in the sense that you say there is a way forward for humanity to survive the climate and environmental emergency, and yet, at one point you say that global heating is going to lead to market collapse. What's your explanation for that?

JUNIPER: So we have now projections coming from environmental economists and scientists who are telling us about the potential consequences, and I say potential because we still have time to avoid the worst of this, but potential consequences down the track, arising from three or even four degrees of global warming. This is a world in which humankind has never lived. And indeed, the temperature in 2024, the average global temperature, was the highest on planet Earth for about 125,000 years, so before the last ice age. And so we've never experienced the kinds of conditions that are now just around the corner, and even with the relatively modest level of global warming that we've already seen so far, it's estimated that there could be a 20% reduction in global GDP as a consequence of that by the middle of this century. And so what we're leaning into beyond that, in terms of two and a half, three, three and a half, four degrees of global warming will lead to consequences that will be economically catastrophic, as well as catastrophic for society, because of the consequences of all of that for people, in terms of heat stress, lack of water, food prices, crops failing, damage to infrastructure, all of those things will be extremely expensive and make the kind of economy that we have at the moment real in the face of all of that, because it's not resilient, the system we've built, it's not resilient to that level of change and shock. But you're right, Steve, I am optimistic in seeing that we have all of the technology, we have all of the good policy ideas, but we need to shift some of the fundamentals in order to be able to get there. And actually, I do quote one of my great heroes, Dwight D. Eisenhower, the architect of the D-Day landings, who shared some fantastic wisdom, he said "if a problem can't be solved, make it bigger.” And that's really the spirit in the last part of my book, where observing the failure to deal with environmental issues effectively over 40 years, might it help if we make the problem bigger and see it as something beyond simply an environmental or a green issue? And that's really where I finished the book with some thoughts in that space.

Tony Juniper is the Chair of Natural England, the official Government organisation working for the conservation and restoration of the natural environment in England. (Photo: Courtesy of Tony Juniper)

CURWOOD: You at one point and may I quote you, you will perhaps recall these words, "I believe the priorities can be summed up into six words, renewable, sustainable, circular, regenerative, restorative and fair". Is this what you call “thrivalism”?

JUNIPER: So I came with a new kind of political “ism,” because having researched and thought about this subject matter now for many years, I've reached the conclusion that capitalism in its current form, won't be able to help us avoid quickly enough the environmental crisis that we're facing. And equally, I reached the conclusion that socialism and communism equally, are not capable of getting us through the bottleneck that we're now in. And so based upon those six words, I propose the idea of thrivalism, which is the framework we might adopt for 10 billion people thriving on a living planet. And it will be 10 billion people that will be with us by 2050 and if we're all going to thrive on a living planet, we're going to need to look at meeting everyone's needs in a different way to how we do at the moment. And I reached the conclusion that neither capitalism nor socialism are fit for purpose. We need a new way of being able to achieve the scale of change that's necessary.

CURWOOD: Tony Juniper's book is called Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

JUNIPER: My absolute pleasure, Steve, so nice to have a discussion on these complex subjects.

Related links:

- Learn more about Tony Juniper

- Follow Tony Juniper on Bluesky

- Follow Tony Juniper on X

- Purchase Just Earth: How a Fairer World will Save the Planet from Bookshop.org to support both Living on Earth and independent book shops

[MUSIC: Morninglightmusic, “Joy” single, MorningLightMusic]

DOERING: Next week on Living on Earth, buoyed by recent victories in climate cases in the state courts, youth plaintiffs are again setting their sights on the federal government.

PARENTEAU: It's a mix of constitutional claims and statutory claims based on statutes. The constitutional claims are a right to life and liberty. And by right to life, the plaintiffs are saying it's not just any life, right? It's a healthy life, a right to live in a healthy environment where your future is secure, where your opportunities are available to you to grow and prosper, be happy, even. So, their concept of right to life and liberty is very, very broad, broader than anything the United States Supreme Court has ever recognized. That's the biggest reach of, of this case, okay? So, you know, it's very unlikely that there are 5 votes on this Supreme Court to recognize that kind of sweeping constitutional right. I applaud the plaintiffs for trying. I think the facts justify recognition of a right like that. I think the science supports what they're claiming as interfering with their right to life and liberty. That's a big reach. The one that intrigues me the most, and there's a sort of a series of claims around this one, is that the president doesn't have the authority to do what he's doing. And we've seen this in other contexts whether it's deportation, whether it's birthright citizenship, he is an imperial president. Some call him, you know, a would-be king and so one of the thrusts of the Lighthizer case is to say, Trump just doesn't have the authority he's claiming.

DOERING: The new federal youth climate case, next week on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Morninglightmusic, “Joy” single, MorningLightMusic]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Daniela Faría, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Frankie Pelletier, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth