Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet

Air Date: Week of June 27, 2025

Tony Juniper’s newest book, Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet. (Photo: Courtesy of Bloomsbury)

In his recent book Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet, Tony Juniper explores how tackling economic inequality within and between countries will go far to solve the climate and biodiversity crises. Tony Juniper is a former head of Friends of the Earth UK, has long advised King Charles III on the environment and climate and now chairs Natural England, a government conservation agency. He joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the transformation that’s urgently needed to allow planet and people to thrive.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

It’s no secret that the poorest people on earth bear the brunt of the climate crisis yet are the least responsible for it in the first place. And they are often faced with exposure to toxic pollution, lack of access to quality green space, as well as barriers to education and economic opportunities. In his recent book, Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet, Tony Juniper explores how tackling economic inequality within and between countries will go far to solve the climate and biodiversity crises. Tony Juniper is a former head of Friends of the Earth UK, has long advised King Charles III on the environment and climate and now chairs Natural England, a government conservation agency. Tony, welcome back to Living on Earth!

JUNIPER: It's so good to see you again Steve, it's been too long.

CURWOOD: Tony, a major part of your book points out that we're stuck in the environmental emergency because of income disparity, that our focus on economics, rather than the environment, leads us in a position where we have a lot of people who don't have so much money, and a few people that have a lot and that that's sort of the gordian knot to unwind the environmental crisis. Why is that so?

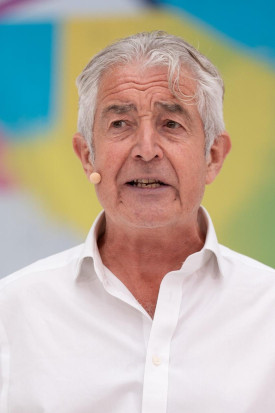

Tony Juniper at the World Economic Forum's Annual Meeting of the New Champions, also known as Summer Davos, which was held in Tianjin, People's Republic of China in 2016. (Photo: Jakob Polacsek, World Economic Forum Flickr, CC BY NC SA 2.0)

JUNIPER: Well, these wealth, these wealth disparities, and indeed, there are disparities that link to race as well, which you know, are really fundamental blockages to where we need to go. And so on the income inequalities, you know, we have a worsening level of inequality in the world. It started at the beginning of the 1980s and it's been getting progressively worse ever since, to the point today where a couple of thousand billionaires control more wealth than the entire 4 billion of poorest people in the world. What is the remedy to that? Well, one answer that is debated endlessly, and which is the priority of most governments is to achieve economic growth. Now there are many upsides from economic growth, but when much of the benefit is going to a tiny minority of already rich people, I think we do have to ask questions about the distribution of the wealth when it is poverty that is blocking the environmental challenges being met. And there's one statistic from the World Bank, which I thought was quite enlightening, it set out how between 1996 and 2021, so a 25 year period, of all the wealth created in the wild over that time, and it was a spectacular quantity of trillions of dollars of GDP, 38% of it went to the 1% of already most wealthy people. And if you look at the top 10% of people, then the disparity is greater still, and so we're running on a treadmill and we're not going forward in terms of leveling out these massive income disparities as we pursue more and more economic growth. It's getting worse, and yet that is the biggest problem we have in tackling global warming and the degradation of ecosystems and consumption of resources is because we're always trying to protect the interests of the least well off. That's one of the reasons why we continue on that treadmill, is because we see it as being of benefit to low-income people.

CURWOOD: Well, wait, let me just stop you right there. The environmental degradation you write about in your book, really hits low-income people harder than the rich folks.

JUNIPER: Yes, it does.

CURWOOD: So why would low-income people be opposed to dealing with the environmental crisis?

The Amazon is one of the worlds’ most biodiverse places on earth and it plays a crucial role in regulating the world’s and carbon cycles. (Photo: CIFOR, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

JUNIPER: They're not. Very often it's the elites who run governments who cite the least well off people as the reason why we shouldn't move to sustainable agriculture, because it will make food more expensive. You see that here in the British media quite a bit. We've been told for many decades that we didn't want to invest in upgrading our water treatment systems in this country because this would put up bills for poor people, and so our rivers now have high levels of sewage waste in them because we didn't invest, because we wanted to keep bills low. And at the moment, we have a renewed focus on the targets to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions in this country, with lots of opposition coming against targets for renewable energy because of the impact this will have on poorer consumers. And so the reasons why environmental policies are challenged often circle back onto the plight of least well off consumers when it is, as you say, Steve, those least well-off consumers who are suffering the worst consequences of environmental degradation in the first place, whether it be toxic pollution, the effects of climate change, or limited access to green space.

CURWOOD: So you write in your book, Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save The Planet, about income inequalities within nations, as well as among nations. Looking at the United States, what's our degree of economic inequality? And how do you think that affects how the US is addressing the climate and environmental emergency?

JUNIPER: Well, the United States is one of the countries that is extremely unequal. There are more unequal countries, but they're not at a level of advancement of the United States. And as I describe in the book, you know, there are many levels of how this manifests itself, in terms of the differences between the well off and the least well off. And in the United States, you know, there are very poor communities who suffer disproportionate impact from environmental degradation, and there is a rich literature formed from an environmental justice movement in the US that has set out in a great deal of detail with data revealing the extent to which it is nonwhite communities, Black and Hispanic communities, who suffer a hugely disproportionate level of toxic pollution. And also when it comes to some of the natural disasters, well less natural as time goes by, some of the disasters that accompany rapid global warming. I do talk a little about the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and how it was the Black communities in New Orleans who felt the brunt of that storm, and who were uniquely vulnerable in that part of the world because of where they lived and the lack of facilities they had and the extent to which they were exposed, just through their poverty, to a very unpleasant set of experiences that followed that storm. And so across the world, you see different manifestations of this and some of them, you know, they come back to us in the Western countries when it comes to the global dimensions of how you have very different experiences arising from environmental change.

Pictured above is the New York Stock exchange. In his book Just Earth, Tony Juniper argues that inequality is the main obstacle that blocks addressing climate change. (Dietmar Rabbish, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 4.0)

And I do actually cite the example of Afghanistan, a war in which both British and American troops, alongside many other coalition partners were involved, and I talk about that conflict from the point of view of a British Army General who gave me a briefing about his insights from two tours of duty in Afghanistan. And who told me about the extent to which that conflict was in large part fueled by the consequences of climate change, with very poor people living in rural areas unable to feed their families because of the way in which there was no water to sustain their crops, they had destitution that followed this then leading them to take money from the Taliban to join their forces and then to engage in that very bitter and ugly battle that went on for so many years, but which has its roots that general told me, in the consequences of global warming. And so this disparity in how the environmental consequences fall on different communities ,it's not only within nations it also can come back like a boomerang to hit us, even in countries where we feel quite secure and relatively well-off compared with some other countries.

CURWOOD: Tony, I know early in your career, you spent a fair amount of time in the forests of the planet, especially some of the tropical forests that are so important, and you say in your book that the percentage of people on the planet who are still indigenous is quite small compared to the amount of land and forests that they still are able to manage and protect. What are those numbers, and how are we doing with supporting them in keeping this protection going?

JUNIPER: So indigenous peoples constitute today a few percent of the global population and yet they manage at least half of the protected areas and the remaining biodiversity on the earth. And this is of material interest, because if you look at a map of the Amazon basin and where the remaining forests are, and then if you overlay that map of the remaining forests with where the indigenous territories are, where those people have control of the forests in Peru, in Colombia, and in Brazil, you see a very high correlation between the indigenous controlled lands and where the forest still remains, and this is a reflection of their worldview. So those people regard the forest as a living, spiritual entity. For Western derived cultures, the forest is a place where you can take timber from where you can mine iron and minerals and precious metals, including gold and it's a place where the forest can be cleared to make way for cattle pastures and for soya plantations. And the difference between an intact forest and a soya plantation at its most basic level, it is about the philosophical perspective of the people who are looking at the forest. One sees the forest as a market opportunity in the global economy. The other sees the forest as a sacred presence which needs to be handed on intact for the benefit of future generations, as well as the rest of life on Earth. So the role of the indigenous communities could not be more important at this emergency juncture in the history of humankind, when we can see now the effects of global warming taking on really quite troubling dimensions, and as we look into the specter of a mass extinction of animals and plants, it's that indigenous worldview that offers us the prospect for salvation, because the indigenous worldview is not about nature over people, it's about nature and people, and looking after nature for the people. And that is something that we can still do if we take action quickly enough, but we won't do it by continuing with our process of a quest for unending economic growth and expecting that to solve all of our problems, especially when most of that growth is going to a small proportion of already very wealthy people.

Tony Juniper (right) with Laura Fox (left), a Chronos Sustainability Specialist on Biodiversity and Agriculture. She worked with Tony Juniper on his new book Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet. (Photo: Courtesy of Tony Juniper)

CURWOOD: By the way, what is the income inequality among indigenous groups?

JUNIPER: Among indigenous groups, they tend to be very egalitarian and they tend to have a chief, but money is something which is relatively new to them and it will vary from community to community in terms of their continued cohesion as an indigenous society compared with those that have had more contact with the outside world, but they tend to be societies that work at a small scale and which thrive because people share things.

CURWOOD: Your book is basically optimistic in the sense that you say there is a way forward for humanity to survive the climate and environmental emergency, and yet, at one point you say that global heating is going to lead to market collapse. What's your explanation for that?

JUNIPER: So we have now projections coming from environmental economists and scientists who are telling us about the potential consequences, and I say potential because we still have time to avoid the worst of this, but potential consequences down the track, arising from three or even four degrees of global warming. This is a world in which humankind has never lived. And indeed, the temperature in 2024, the average global temperature, was the highest on planet Earth for about 125,000 years, so before the last ice age. And so we've never experienced the kinds of conditions that are now just around the corner, and even with the relatively modest level of global warming that we've already seen so far, it's estimated that there could be a 20% reduction in global GDP as a consequence of that by the middle of this century. And so what we're leaning into beyond that, in terms of two and a half, three, three and a half, four degrees of global warming will lead to consequences that will be economically catastrophic, as well as catastrophic for society, because of the consequences of all of that for people, in terms of heat stress, lack of water, food prices, crops failing, damage to infrastructure, all of those things will be extremely expensive and make the kind of economy that we have at the moment real in the face of all of that, because it's not resilient, the system we've built, it's not resilient to that level of change and shock. But you're right, Steve, I am optimistic in seeing that we have all of the technology, we have all of the good policy ideas, but we need to shift some of the fundamentals in order to be able to get there. And actually, I do quote one of my great heroes, Dwight D. Eisenhower, the architect of the D-Day landings, who shared some fantastic wisdom, he said "if a problem can't be solved, make it bigger.” And that's really the spirit in the last part of my book, where observing the failure to deal with environmental issues effectively over 40 years, might it help if we make the problem bigger and see it as something beyond simply an environmental or a green issue? And that's really where I finished the book with some thoughts in that space.

Tony Juniper is the Chair of Natural England, the official Government organisation working for the conservation and restoration of the natural environment in England. (Photo: Courtesy of Tony Juniper)

CURWOOD: You at one point and may I quote you, you will perhaps recall these words, "I believe the priorities can be summed up into six words, renewable, sustainable, circular, regenerative, restorative and fair". Is this what you call “thrivalism”?

JUNIPER: So I came with a new kind of political “ism,” because having researched and thought about this subject matter now for many years, I've reached the conclusion that capitalism in its current form, won't be able to help us avoid quickly enough the environmental crisis that we're facing. And equally, I reached the conclusion that socialism and communism equally, are not capable of getting us through the bottleneck that we're now in. And so based upon those six words, I propose the idea of thrivalism, which is the framework we might adopt for 10 billion people thriving on a living planet. And it will be 10 billion people that will be with us by 2050 and if we're all going to thrive on a living planet, we're going to need to look at meeting everyone's needs in a different way to how we do at the moment. And I reached the conclusion that neither capitalism nor socialism are fit for purpose. We need a new way of being able to achieve the scale of change that's necessary.

CURWOOD: Tony Juniper's book is called Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

JUNIPER: My absolute pleasure, Steve, so nice to have a discussion on these complex subjects.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth