May 23, 2025

Air Date: May 23, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Public Lands Reprieve

View the page for this story

Last-minute changes in the House budget reconciliation bill included scrapping one of the more controversial amendments that would have sold off public lands in the southwest to private developers. But the overall bill isn’t a complete win for the environment, with even deeper cuts to clean energy tax credits added at the last minute. Wyatt Myskow is the Mountain West Correspondent for Inside Climate News and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain. (09:11)

Listening on Earth: Cenzontle and Zocalo

View the page for this story

This week’s “Listening on Earth” sounds come from listener Flynn Wendling, who shared the call of a mockingbird (or Cenzontle in Spanish) in Mexico that became his morning wake-up call; and from Living on Earth Producer Paloma Beltran, who visited Mexico City’s Zocalo and captured the sounds of a celebration of 700 years since the founding of Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City. (01:46)

Trump Ignores Social Cost of Carbon

View the page for this story

A new White House memo instructs federal agencies to disregard the economic impacts of climate change in their regulations and permitting decisions. This metric is known as the “social cost of carbon” and it has been used for decades to guide policy so that it considers the economic realities of our changing climate. David Cash served under President Biden as the New England Administrator for the US Environmental Protection Agency and he joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss. (10:41)

EPA Cancels Climate Justice Grant

View the page for this story

Last year, a nonprofit group in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was awarded a large federal grant as part of a $2 billion climate justice program through the Inflation Reduction Act. But now that climate and environmental justice work are non grata at the federal government, their grant has evaporated. The Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports. (06:19)

Protecting Tenerife's Marine Marvels

View the page for this story

One of the recipients of this year’s Goldman Environmental Prize is helping to protect an especially biodiverse part of the oceans around the Canary Islands. Carlos Mallo Molina was previously a civil engineer who also loved scuba diving. When he found out about plans to build a massive port on the island of Tenerife that could have devastated the local marine life, he decided to leave construction and dedicate his career to protecting the oceans. He joined Living on Earth Executive Producer Steve Curwood. (11:57)

Seagrass "Gardening"

View the page for this story

Seagrass is a foundation of marine ecosystems and stores as much as 35 times more carbon than a tropical rainforest, but warming ocean temperatures and other threats are wiping seagrass out. There is hope, though, as a project to “garden” or cultivate more resilient varieties is making waves along the U.S. East Coast. Hosts Aynsley O’Neill and Jenni Doering chat about the benefits and promising results of this seagrass “gardening.” (06:26)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250523 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: David Cash, Boze Hancock, Carlos Mallo Molina, Wyatt Myskow

REPORTERS: Julie Grant

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering,

O;NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

An attempt to sell off half a million acres of public lands with the budget reconciliation bill backfires.

MYSKOW: These public lands are owned by the federal government in trust for the American people. They are to be enjoyed by the American people, to be used at our benefit. What this is doing is shutting out the public from participating in, what is the future of those public lands?

DOERING: Also, the Trump administration cancels environmental justice grants that fund workforce development.

MANSPEIZER: When I found out that we got the grant, I actually cried. Because I knew it would enable us to do such good work and to make the difference in so many people's lives.

DOERING: We’ll have those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Public Lands Reprieve

One of the proposed areas for development in Nevada was a swath of public land near the Gold Butte National Monument. (Photo: Bob Wick, BML, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

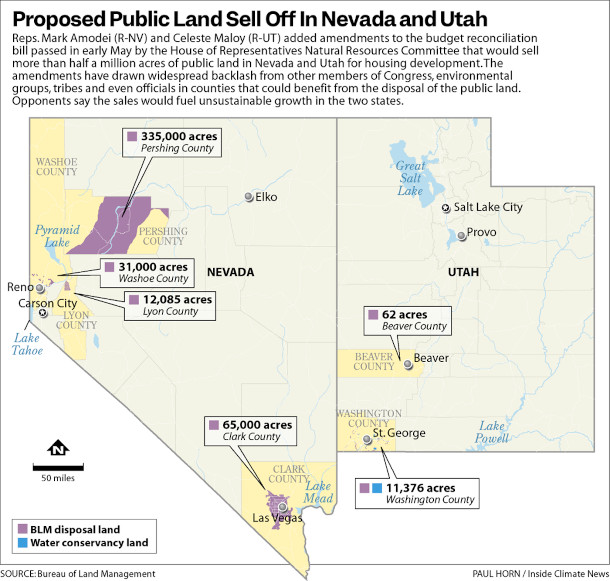

With just a one vote majority, mostly along party lines, the House has passed what President Trump likes to call the “One Big, Beautiful Bill” to deliver on the bulk of his legislative agenda. Republicans are using what’s called budget reconciliation to allow the legislation to skip the Senate filibuster so it can pass with a simple majority in that chamber as well. At the last-minute GOP leaders made some key changes to the House bill, scrapping one of the more controversial amendments that would have sold off public lands in the southwest to private developers. Although the original provision came from Republican lawmakers, so did the push back against it, showing that care for our shared home can concern us all regardless of party affiliation. However, the overall bill isn’t a complete win for the environment, since another of those last-minute changes included some even deeper cuts to clean energy tax credits. Wyatt Myskow is the Mountain West Correspondent for our media partner Inside Climate News and he’s here to explain. Hey Wyatt, welcome back to the show!

MYSKOW: Thanks for having me.

O'NEILL: Well, so I've got to say these last minute changes have been a little tricky to keep track of. What's your reaction to the bill that the House has managed to pass?

MYSKOW: Well, it's notable that the amendment to sell off nearly half a million acres of public land in Nevada and southern Utah has been stripped from the bill. And I think there's a lot of climate things to talk about on this bill, but on the public lands front, it's a huge win for conservationists and recreationalists across the country. That amendment to the bill was deeply unpopular. It attracted a wide coalition from Nevada and Utah's other congressional members to local counties and towns to conservation groups, environmental groups, climate groups, all coming out in opposition. The amendment was stripped. Those lands will not be sold off, and it was led mainly by Congressman Ryan Zinke, which was quite notable. Listeners may remember his name. He was the former interior secretary under the first Trump administration. A man who many conservationists did not like that much has been a leading voice in fighting these public land sales. And he likened this fight, this amendment, to his San Juan Hill, referring to the battle in the Spanish American War, saying, after the bill had passed without this amendment, that once the land is sold, we will never get it back, and that God isn't creating more land. So this amendment really struck a chord with a variety of people across the country, and now it's gone.

O'NEILL: Well so half a million acres of public land across Utah and Nevada, that's a pretty massive swath. What would that have looked like? What was the controversy here, aside from just selling off public lands?

A graphic showing the original public land sell-off proposals from the budget reconciliation bill. These provisions were ultimately cut from the legislation before it passed. (Photo: Paul Horn, Inside Climate News)

MYSKOW: So those amendments proposed selling off those half a million acres for affordable housing in the two states, which is not necessarily controversial, but what made it so controversial is the nitty gritty of it. So there was nothing in the amendments to actually require that land to be sold exclusively for affordable housing, and some of that land would also go towards mining and other interests. One thing to really note, especially on the Nevada side of this, is that all the land identified to have been sold off had been proposed in already pre-existing bills proposed by other members of Nevada's congressional delegation. One, for example, the Southern Nevada Economic Development and Conservation Act would open up some public land near Las Vegas to expand the growth of the city, but it had a lot of aspects to it that made it more palatable to conservation groups. It had water conservation funds, money to go towards protecting other public lands. It would add wilderness designations to other areas in Nevada to further protect other areas. It did a variety of things that this amendments that were proposed in the budget reconciliation bill did not do, and that's what led it to be so controversial. And there was a big fear from tribes, from conservation groups, from other states, other members of Congress, like representative Zinke, that this would be a precursor to more public land sales across the country. That this was the test case, and if this could pass, then other lands would be put up for sale as well.

O'NEILL: And now to what extent do you think that the rather hasty way in which this public lands provision was added to the budget reconciliation bill sort of ultimately led to its downfall?

MYSKOW: The lack of public involvement in this amendment was a huge downfall for it. It was why so many groups and so many other members of Nevada's congressional delegation and across the US as well, came out against this and ultimately got it stripped, because it didn't involve the public. It didn't involve the stakeholders who would benefit from this. Even Clark County, the county that Vegas calls home, was not in support of this, even though they would have benefited from it.

An attempt to sell hundreds of thousands of acres of public land in Nevada and Utah was stopped before the House passed a spending bill on Thursday May 22, 2025. Pictured above is Zion National Park in Utah, which is nearby but would not have been affected by the provision. (Photo: Diliff, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 3.0)

O'NEILL: Now let's talk briefly about the cuts to clean energy tax credits that were also in this House Bill. What has made it into the sort of final version that was passed?

MYSKOW: So under what the House passed, it eliminates electric vehicle tax credits after this year, for the most part, it would also eliminate tax credits for energy efficiency, rooftop solar, more energy efficient homes. And kind of a big deal here is that for clean electricity subsidies, they have to break ground within 60 days to receive any credits and go online by 2029. So it essentially means if you're building some form of clean energy project that qualified for those subsidies, you need to break ground as soon as this bill passes and is signed into law, and you need to be in operation by 2029. So if you can't do that, or if you do break ground somehow, but then maybe you get sued because you maybe had to rush things really quickly, and that lawsuit drags your construction into 2030, well, that's too bad you're out of any of those subsidies. The one exception is for nuclear. This is going to have real impacts on the ground across America, across states blue and red. Industry groups have said that this bill, the way it's currently ran, if it passes, would kill about 300,000 American jobs. It would increase electricity bills by 51 billion for American families and businesses, and ultimately, it means less energy is going to be built, which seems counterintuitive to President Trump's energy dominance plan.

O'NEILL: Well Wyatt, by the way, why was nuclear given an exception, do you think?

MYSKOW: Nuclear is kind of all the rage these days. It's not easy to build. There's still a lot of questions over how feasible this will be long term, just for financing projects. And there's so many questions of, where do you get the uranium needed to fuel nuclear, where you're going to store the waste, so many things. But the federal government, businesses, Wall Street and states and utilities have all really signaled over the past year, a renewed interest in expanding nuclear, and it's something that's fairly bipartisan right now, surprisingly, which has not necessarily been the case historically. And so, it's been able to weather some of these attacks on clean energy investments. Obviously, nuclear is more controversial than other types of clean energy, but nonetheless, there's a lot of interest in it.

O'NEILL: So now, as this heads to the Senate, how do you think that the energy and climate rollbacks might be received there, not just amongst Democrats, but amongst Republicans as well?

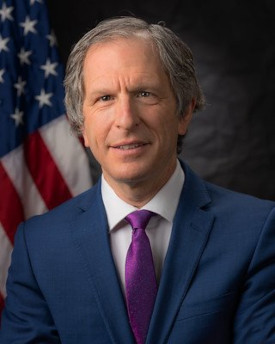

Wyatt Myskow is a reporter based in Phoenix, Arizona for Inside Climate News, where he covers water issues, development, public lands, wildfires and more. (Photo: Alex Gould)

MYSKOW: Well, the Senate, of course, is typically a bit more bipartisan. It's tough to say what exactly will change. Obviously, things are moving, and a lot is happening right now, and we still have days, if not weeks, before we finally know what's going to come out of this reconciliation bill. I would imagine many of this will tweak still. Funding under the Inflation Reduction Act, some of those clean energy tax credits and subsidies, I imagine the final numbers will look different than they do today. The public land front, things will probably look very similar. I'm doubtful anyone in the Senate is going to propose selling off public lands, but you never know. Really, it's all up in the air, but we can expect some form of this potentially to come.

O'NEILL: And we'll have to keep an eye on it. And Wyatt, is there anything else that struck you about this big, beautiful house bill?

MYSKOW: I would say the thing that really struck me on that public lands amendment that has been now been struck out of it, is that in this bill there are many provisions, amendments that are quite controversial. This one was as well, but those other provisions are still in the bill. The public lands, though, is not and I think that speaks to how beloved public lands are by Americans across the aisle. You know, you have hunters and fishers who are not necessarily the most left of leaning people who fought hard to get that provision stripped. So it really speaks to how on some issues, we still have quite a lot of common ground.

O'NEILL: Wyatt Myskow is the Mountain West Correspondent for our media partner Inside Climate News. Wyatt, as always, thank you for taking the time with me today.

MYSKOW: Of course, thanks so much for having me.

O’NEILL: It remains to be seen what will happen when the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” reaches the Senate, but we’ll keep following developments and reporting in the next broadcasts.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Locals Oppose ‘Insane’ Plan to Sell 500,000 Acres of Public Lands for Housing in Nevada and Utah”

- AP | “A Republican push to sell public lands in the West is reigniting a political fight”

- Field & Stream | “Congress Strips Public Land Sell-Off Amendment From Budget Package After Hunters and Anglers Speak Out”

- InsideClimate News | "House Republicans Have Passed a Bill to Gut the IRA. What Happened to All the Supposed Holdouts?"

[MUSIC: The London Symphony Orchestra, “Oh, What a Beautiful a Beautiful Morning” on OKLAHOMA!, by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, Jr. Decca]

Listening on Earth: Cenzontle and Zocalo

The cenzontle, is a Mexican bird famous for its ability to imitate a wide range of sounds. Its name, derived from the Nahuatl language, translates to "bird of 400 voices". (Photo: Panza-rayada, Wikimedia Commons CC BY SA 3.0)

O’NEILL: We’d like to thank our listeners who’ve sent in audio for our “listening on earth” series. Whether you’re at home, out for a stroll, or traveling abroad, you can share a glimpse with us through sound! Like this recording of a Cenzontle or Mockingbird shared by Flynn Wendling.

[CENZONTLE RECORDING]

O’NEILL: Flynn captured this while living in the high desert mountains of Mexico. Every morning a mockingbird would perch just outside his window and sing this song. Now it’s the tune for his morning alarm!

[CENZONTLE RECORDING]

O’NEILL: You can also take inspiration from this recording captured by Living on Earth producer Paloma Beltran during a performance in Mexico City’s Zócalo.

[ZOCALO RECORDING]

O’NEILL: Hundreds of people dressed in their traditional me-SHÍ-ca (Mexica) regalia danced in the city’s central plaza while celebrating 700 years since the founding of Tenochtitlán, which is now Mexico City.

Dancers gather to celebrate the 700th anniversary of the founding of Tenochtitlan, now called Mexico City. (Photo: Oscar Fierro)

[ZOCALO RECORDING]

O’NEILL: To capture sound you can use any sound recording app on your phone, like Voice Memos or Voice Recorder. And for the best audio quality make sure to stand still for at least two minutes without fidgeting or talking. But we do want to hear from you! So be sure to speak clearly and let us know who you are, where you are, what you’re hearing and what inspired you to record the moment. Then you can email the file to comments@loe.org, and we might just use your audio postcard on the air! That’s comments at loe dot org.

[ZOCALO RECORDING]

Related link:

Learn more about the northern mockingbird or cenzontle

DOERING: Just ahead, any budget big or small only works if it factors in likely expenses. But the Trump administration says there’s no need to add up the costs of climate change.

CASH: What's so in some ways outrageous about the latest efforts that the White House is taking is essentially saying there's no cost of climate change. Climate change doesn't exist, and therefore we don't need to take it into account when we're taking regulations. And what that will mean is greater droughts, greater wildfires, loss of life, injuries, all of those kinds of things that are part and parcel of the climate crisis that we're facing.

DOERING: Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joel Mabus, “Tishomino Blues” on Parlor Guitar, by Spencer Williams, Fossil Records]

Trump Ignores Social Cost of Carbon

The social cost of carbon (SCC) refers to the net damages from global climate change that result from an increase in CO2 emissions of one metric ton. (Photo: Ryan T, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

A new White House memo instructs federal agencies to disregard the economic impacts of climate change in their regulations and permitting decisions, unless explicitly required by law. This metric is known as the “social cost of carbon” and it has been used for decades as a way to guide policy so that it takes into account the economic realities of our changing climate. Even in the first Trump administration, the White House used the metric, though they put it only around $5 a ton at the time, far lower than the Obama Administration estimate of $42 a ton. In the Biden White House, a recalculation factored in inflation and the worsening toll of climate change, bumping up the cost to nearly two hundred dollars per ton. David Cash served under President Biden as the New England Administrator for the US Environmental Protection Agency, and he joins us now to explain what a “social cost of carbon” of zero would mean. David, welcome back to Living on Earth!

CASH: Thanks, Jenni, good to be here.

DOERING: So, let’s start by breaking down what the phrase means, the social cost of carbon. What is this all about?

CASH: Yeah, so this is a little bit on the wonky side of things, but really, really important and very different than a lot of the other things that we've seen this administration doing in turning back the climate clock in terms of freezing federal funding and changing regulations. Social cost of carbon means, basically, if we don't stop climate change, what are the costs that we all feel because of climate change? In other words, what are the costs because of the increased chance of wildfires or coastal flooding or drought. Because, when government regulates industry polluters for doing things, government has to justify taking actions right, and that justification is based on what happens if industry is not regulated, right? Government doesn't want to regulate industry just because it's fun to regulate industry. We regulate industry to protect people, because industry will take action sometimes that doesn't take into account the cost of their doing business, and what that cost has on people. So the social cost of carbon is something that's been developed over the last 15/20 years that very methodically and very robustly, uses science, economics to determine what that impact would be, so that when the government makes a regulation the benefits in terms of the reduction of harm, the reduction of costs, has to outweigh what it's going to cost industry, for example, to change technology or to reduce emissions. And what's so in some ways outrageous about the latest efforts that the White House is taking is essentially saying there's no cost of climate change. Climate change doesn't exist, and therefore we don't need to take it into account when we're taking regulations. And what that will mean is greater droughts, greater wildfires, loss of life, injuries, all of those kinds of things that are part and parcel of the climate crisis that we're facing,

DOERING: Right, I mean, just ignoring what's happening doesn't make the problem go away.

CASH: Not at all. I have a quick little metaphor that maybe can help people understand. In the 1960s and 70s, it became more and more obvious that if you drove a car without seatbelts and you got into an accident, much more likely to get hurt, to have injuries, to have deaths, and there was a large cost to a car company not putting in seatbelts. Of course, there was a cost to the company to add the seatbelts. It costs money. It would cost the consumer money. But the government did the analysis, and it showed that actually it was incredibly cheap to put in these seatbelts, and the benefits were huge, the reduction of injuries and costs, and even to like local municipalities, for their police departments or fire departments emergency responders, all of those costs would go down. And so that's exactly what the role of regulation should be is to protect the public from actions that industry takes that they don't put in their bottom line, and the regulations force them to put in their bottom line, and that's exactly what we're trying to do with climate change.

DOERING: So let's talk about the numbers. You know, the Trump administration is looking to bring this cost to zero. What do our best estimates say that the cost actually is in comparison?

CASH: Well, in the Biden administration, it was up to $190 per ton. So what that means is that, on average, if a ton of carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere through cars or through a power plant, it would cost about 190 dollars in terms of damage. Now you could see how that could, 190 dollars, could add up pretty quickly, right? Analysis from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration last year showed impacts of at least 180 billion dollars and that's taking into account the impacts of floods and drought and wildfires and things like that. So that's what the cost of carbon is supposed to capture. What the incremental cost of each additional ton of carbon in the atmosphere will result in that you're going to have to pay for if you go to the hospital that people out in California paid for because they don't have homes anymore. And by the way, industries all over the country are taking this into account. Insurance, you might have read in the news how insurance is much, much harder to get now in California and Florida and other places that are hit by climate change really hard, and that's because the insurance companies have to take into account those costs. They're real. So for the White House to be saying, oh, they're not real, climate change is not real, it doesn't cost anything is outrageous.

President Trump’s White House has instructed federal agencies to disregard climate change on a number of levels. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: You know, the Trump Administration has said there's just so much uncertainty in how much carbon dioxide costs society that it's not even worth counting that cost. What's your response?

CASH: There's always uncertainty. Of course, there's uncertainty. This is a dynamic, changing landscape, and our understanding changes. Of course, there's uncertainty, but if government never made decisions because there was uncertainty, government would never make decisions because there's always uncertainty. So the key is in wise governance is how you take into account those uncertainties. When you make your decisions, you acknowledge them, and then you invest in science to reduce those uncertainties. But guess what the White House is also doing… It's reducing its investment in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's science. It's getting rid of EPA’s science efforts to study climate change. So, of course, uncertainties will not be diminished given the work that they're doing. In fact, they're even reducing things like hurricane forecasting. I mean, states and municipalities all over this country use those forecasts to prepare for the next big hit. The Trump Administration is taking away that information as well.

DOERING: And so David, what might a social cost of carbon of zero mean in the real world when it comes to projects that the federal government is considering.

Some experts have calculated the financial impact from climate-worsened disasters in the U.S. to be around $180 billion in 2024 alone. (Photo: Daniel Lincoln, Unsplash)

CASH: Yeah. So basically what it would mean, it would allow the EPA, for example, to diminish the effectiveness of regulations such that cars could pollute more, factories could pollute more. Gas plants, coal plants could produce more. All of which would increase the chance of greater storms, greater flooding, greater wildfires, greater drought, greater incidence of incredibly hot days in the summer where people will get more cases of asthma, more respiratory disease, all of those kinds of things. So it will have a real world impact. And you know, let's say they do that, and a year from now, you could go into hospitals and see an uptick in asthma rates, for example, on emergency room visits, which, by the way, you may recall, I live in New England, and about a year or so ago we had the wildfires that were sending smoke from Canada to the Boston area. In all of New England, we saw an uptick of emergency room asthma cases, kids coming in because of that… well, so we'll see more of that.

DOERING: Yeah, I mean that deadly particulate matter kills something like 300,000 people in the US alone every year. According to the World Health Organization, it's coming from wildfires, it's coming from smokestacks, tailpipes. To what extent does the social cost of carbon or another metric capture that societal toll?

David Cash is the former Administrator of EPA's Region 1, New England. (Photo: Courtesy of the EPA)

CASH: When EPA regulates, it takes into account all of the different pollutants, and so particulates is one of the most important because it has such an on-the-ground impact to people's ability to breathe, and so regulations do capture that. And at this point, this particular memo from the White House that said it was going to count the social cost of carbon as zero does not impact analyses at this point of particulates, but we know that that's coming. We know there's going to be relaxing of using the kinds of standards that protect people's health and protect the ecosystems upon which we all depend.

DOERING: David, what do you think people need to keep in mind when they hear a story like this coming out of the current federal government?

In addition to the financial cost of carbon pollution, particulate matter from emissions also takes a toll on public health, especially for vulnerable populations. (Photo: Indiana Public Media, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CASH: I think they have to figure out how to speak out, how to speak out when they hear news like this, and then understand that what this administration is doing is making their environment not as safe for them, and that will have an impact on their family, that will have an impact on their community, that will have an impact on their farms. By the way, a kind of interesting sidebar is that when the US Department of Agriculture announced that they were going to cut their climate forecasting, farming associations got very concerned and complained a lot about it, so that they reinstated them. So we all have to be vigilant to protect the science and the wonky regulatory things like social cost of carbon, we have to protect those so that our families are protected.

DOERING: David Cash is the former US Environmental Protection Agency Administrator for New England. Thanks so much for joining us, and we'll talk to you again soon.

CASH: Great, thanks, Jenni.

Related links:

- The New York Times | "What’s the Cost to Society of Pollution? Trump Says Zero."

- Legacy EPA info about the Social Cost of Carbon

- Watch an explainer from Resources for the Future about the Social Cost of Carbon

[MUSIC: Jacqueline Schwab, “Miss Dumbreck” on I Lift My Lamp: Illuminations From Immigrant America,” Traditional Scottish reel/arr. Jacqueline Schwab, Sono Luminus]

EPA Cancels Climate Justice Grant

Landforce crews pulled weeds and dug holes for new trees in April 2025 in front of the Braddock Civic Center near Pittsburgh. (Photo: Julie Grant, The Allegheny Front)

O’NEILL: Last year, a nonprofit group in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was awarded a large federal grant as part of a $2 billion climate justice program through the Inflation Reduction Act. But now that climate and environmental justice work are non grata at the federal government, their grant has evaporated. The Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports.

GRANT: A crew of about fifteen workers has been digging holes on a warm spring day, to plant trees on the hillside in front of the Braddock Civic Center near Pittsburgh. They’re actually re-digging the holes - the last two times trees were planted here, they died.

MARKEE: So we've come here to kind of apply our professionalism and our expertise, get these ready…

GRANT: Rick Markee is a site supervisor for Landforce, a non-profit that trains people to do landscaping, tree pruning, trail construction, and other skilled outdoor jobs. Senior site supervisor Shawn Taylor sees many benefits from this work.

Landforce career counselors talk with crew members on site about their plans to transition into the workforce. (Photo: Julie Grant, The Allegheny Front)

TAYLOR: It’s helping to keep the folks keep folks employed as well as giving a hand to communities, helping communities improve, whether it's air quality, shade, park areas.

GRANT: Landforce recruits from the Allegheny County jail, probation offices, community centers, and bus stops -- anywhere they can put a flyer. Teya Johnson is 23 years old, and is new to the Landforce crew. She was unemployed when she first saw the group’s flyer.

JOHNSON: It caught my eye, it was actually different. I never actually heard anything about Landforce ever in my life until I seen that. So it was actually pretty impressive for me.

GRANT: Even before land stewardship and landscaping skills, Johnson and her cohort spent their first month at Landforce learning everything from how to open a bank account to the habits they need to hold a job.

JOHNSON: The skills is not just for work. You know, you come outside every day, wake up, not just focusing on work. You have to focus on your mind too as well and inside your emotions to actually be great and have your A-game.

GRANT: Landforce hires a cohort of about 15 people a year in the Pittsburgh area, who’ve ranged in age from 18 to 63.

MANSPEIZER: So, Landforce combines workforce readiness and environmental stewardship.

GRANT: Landforce CEO Ilyssa Manspeizer says over nearly ten years, they’ve trained more than 200 people.

MANSPEIZER: We hire, train and hire people who are typically excluded from family sustaining jobs. We provide intensive training, we provide transitional employment and we provide support to future jobs for them.

Landforce 2025 crew members Teya Johnson, Trevon Matthews and Jerome McKinney. (Photo: Julie Grant, The Allegheny Front)

GRANT: And Landforce had been slowly planning for its own growth. Last year, that effort got a kickstart: it was the lead organization awarded a $15 million community change grant through the Environmental Protection Agency. The grant was shared with a similar group called Power Corps in Philadelphia, along with several subawardees – those are other organizations that will help with their efforts.

MANSPEIZER: When I found out that we got the grant, I actually cried. Because I knew it would enable us to do such good work and to make the difference in so many people's lives.

GRANT: Landforce added staff members, and planned to increase the size of its yearly cohort. And with the help of that grant money, it started creating a whole new business for them to learn, one focused on reusing the wood its crews find around Allegheny County.

To do that, Landforce leased a warehouse on the east end of Pittsburgh in February for what they call The Mill. Ed Johnson is the director of wood re-use there.

JOHNSON: All of our material we recover out of the waste stream here within a 10 or 15-mile radius of the east end.

GRANT: Johnson says the high-quality lumber they collect and process can be used by furniture and cabinet makers, and the other wood will go toward palettes and other lower-grade products. But it’s the waste from that wood processing that’s the real star at The Mill: They’re making something called Biochar, it’s a carbon product made from wood chips that, when mixed into the soil, reduces lead and heavy metals.

From right: Landforce employees Ilyssa Manspeizer (far right), Jasimine Cooper, Thomas Guentner and Ed Johnson, along with subawardees Erin Copeland of the Allegheny County Conservation District, Grounded Strategies’ Greg McAuliffe and Kelly Henderson, and Penn State’s Tom Bartnick at The Mill. (Photo: Julie Grant, The Allegheny Front)

COPELAND: ... which is very important because we have a lot of legacy heavy metals in our soil.

GRANT: Erin Copeland is the program team manager at the Allegheny County Conservation District, which is a sub-awardee on the EPA grant. They plan to help to get Landforce’s biochar to vacant lots and local farms.

COPELAND: And so the biochar once it's incorporated into the soil it doesn't allow for plant uptake of that lead anymore and so it really helps urban farmers who want to be growing food in the city.

GRANT: Early this year, using money from the grant, Landforce spent over a million dollars to buy equipment for the sawmill equipment (required to be made in the US), including a log splitter, various trucks, and the biochar kiln - But like many other federal grants, Manspeizer says there’s been chaos around their grant in recent months.

MANSPEIZER: That funding has been frozen, unfrozen, frozen, and remains frozen now.

GRANT: And then in late April, the grant money was unfrozen again. Within days, her group sent in a progress report that was due, showing that despite the on-again, off-again funding, they have been able to meet all of the grant metrics.

Landforce plans to take the waste wood, like this, from around Pittsburgh to The Mill to be turned into usable lumber or a soil amendment called biochar. (Photo: Julie Grant, The Allegheny Front)

MANSPEIZER: Unfortunately, the very next day we got a termination notice from the federal government, from the EPA, that they were planning on terminating our grant.

GRANT: EPA confirmed this in an email, saying that the Landforce application no longer supports the administration priorities and the award has been cancelled. Manspeizer says this loss of funding is painful, but Landforce will survive.

MANSPEIZER: We may not be able to achieve everything that we wanted to achieve. That we had expected to in this great year that we have planned ahead, but we will make it to 2026.

GRANT: But they won’t be able to train as many people as they’d planned,- people like Teya Johnson…

JOHNSON: You know, you don't get that much of an opportunity to do better and achieve better things in your life.

O’NEILL: That’s Julie Grant reporting for the Allegheny Front. Landforce is currently working on an appeal of the EPA’s grant termination decision.

Related links:

- The Allegheny Front | “EPA Terminates $15M Climate Justice Grant to Pittsburgh and Philly Non-Profits”

- Learn more about Julie Grant

[MUSIC: Duncan-Meyer-Thile, “Mostly Six Eight” on Goat Rodeo Sessions, by Edgar Meyer-Chris Thile-Stuart Duncan, Sony Classical]

DOERING: Coming up, chances are you don’t think much about seagrass unless it’s tickling your feet at the beach. But it’s very important for the health of the oceans and the planet. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Biréli Lagrène Gipsy Poject, “Place du Terte” on Generation Django, Francis Dreyfus Music SARL, a BMG Company]

Protecting Tenerife's Marine Marvels

Port construction can have major environmental impacts on the ocean such as damaging the seabed and creating coastal runoff. (Photo: Megha Engineering and Infrastructures Ltd, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Our oceans play a crucial role in sustaining life on Earth. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration the oceans absorb up to 30% of annual carbon dioxide emissions, which makes them the world’s largest carbon sink. They’re also rich in biodiversity that supports ecosystems and economies across the globe. And one of the recipients of this year’s Goldman Environmental Prize is helping to protect an especially biodiverse part of the oceans around the Canary Islands, a Spanish archipelago just off the coast of Morocco. Carlos Mallo Molina was previously a civil engineer who also loved scuba diving. When he found out about plans to build a massive port on the island of Tenerife that could have devastated the local marine life, he decided to leave construction and dedicate his career to protecting the oceans. He spoke with Living on Earth Executive Producer Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: So let's begin by having you describe the marine protected area in the Canary Islands that's of so much concern.

MOLINA: So, yeah, the Canary Islands are our Spanish Hawaii, so you can imagine, and Tenerife is the biggest island of the eight, and in the southwest of the island, there is this marine protected area that is called the Zona Especial Conservación Teno-Rasca, which means a special protecting zone, which is an MPA or a marine protected area. And why is protected is because there is so much life. We have population of whales all year round. We have sharks. We have like a giant squid. We have like invertebrate sea turtles. It's just a hot spot of biodiversity in Tenerife.

CURWOOD: And how big is the marine protected area, by the way?

MOLINA: So it's 170,000 acres, or 70,000 hectares, which is roughly 60 kilometers by 8 kilometers, more or less.

The ocean is home to beauty, but also a multitude of marine animals and species and is the biggest carbon sink. (Photo: Michal Strzelecki, Wojtek Strzelecki & Jerzy Strzelecki, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Just describe Fonsalía for me right now.

MOLINA: So Fonsalía is a port that was going to be hosting 470, recreational boats, big ferries, cruises, just a lot of ships. The shape of the port was going to be a mega port with an island port. So basically it's rounded. It's a very different shape of port that has a lot of impact underwater seabed. And basically it was going to be the connection with the, what we call in the Canary Islands, is the green islands. So it's the La Gomera, La Palma and El Hierro. So, yeah, that's, that's pretty much. What is it.

CURWOOD: So going from constructing a road to the port to being a Marine conservationist is a bit of a leap. Tell me about the day that you said, Well, wait a second, I've got to change what I'm doing.

MOLINA: Yeah. So I think working in Tenerife as an engineer and like understanding the impact that engineers can do with construction, and being aware that sometimes as an engineer, we try to do environmental assessment, but when it comes to the reality, the assessment is far away from the impact that we are actually doing. It opened my eyes to think that the construction should change, and it was when I realized all the impact that I could change by changing my life and doing something meaningful for the environment. I just decided to jump into the marine conservation field.

CURWOOD: And so you created the non-governmental organization, Innoceana in part to combat this infrastructure development. Tell me, how did the establishment of your group help support the fight against the port?

MOLINA: In 2018, 2019 the government started talking about Fonsalía like, hey, we are going to start thinking about building this port finally, because this port is from the last century. So the planification of the port started in at the end of the 20th century. So when all of this started again to be a reality, we just put the effort of the organization in supporting this citizen platform called Salvar Fonsalía. And in this platform there were amazing people, from biologists to lawyers, and I was the engineer. So I was the civil engineer who used to be on the other side of development, and I changed into this side, so that, I think that key role was important to convince the authorities that it's not just about biologists trying to save the whales. Also, there is engineers and there is other people that want to do something good for this place.

Ships can be a major disturbance for whales and other sea creatures, causing stress. (Photo: al_green, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's just think about it. I'm at the surface, building a port, rebuilding a port that was fairly old, would seem like a smart move for boosting the local economy there on Tenerife. To what extent was there pushback from those in favor of the port?

MOLINA: Yeah, one of the biggest barriers was my own engineering group. So I'm part of the charter civil engineers of the Canary Islands. So my own, let's say family of engineers, were the most interested in building this port, because, you know, construction companies will make this happen. And they were very interested on having this, this development going on, right? So that was a big pushback. They tried to make this port from the very beginning, and I spent so much time speaking to them, speaking to my my colleagues, and trying to convince them that was not necessary. One of the things that we use to convince a lot of people is when this port was planned many years ago, like over almost 30 years ago, there was no knowledge about how important was this marine protected area we were speaking about. So, having all of this information, this new information, was key, and also having Europe on our side, because the European Union is very interested in protecting the nature, which is something I'm proud of. That was all of that combination of things was very important.

CURWOOD: What's been the quality of that biological diversity over the years? How much has it declined?

MOLINA: So there is different ecosystems and different like animals living there. So for instance, when you speak about the seagrass, the seagrass is these plants that live under the ocean and they produce a lot of oxygen and sequestrate carbon. They are carbon sinks. We lost, according to our own studies with my organization, we lost at least like 60% of them in the last 20 years, according with the data from the past. But when it comes to the whales, the population of whales is still there. It hasn't been declined, but the level of cortisol, the level of stress, is just increasing because all of the tourism and all the pollution and, you know, all of the all of the stressors. So yeah, there is definitely getting worse and worse.

Carlos loves the ocean and is the happiest when scuba diving. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: So talk to me about what would have happened to nature with the construction of this port, what was wanting to be done?

MOLINA: Yeah. So first of all, there is, like, different levels of in the construction a port. First you have the actual construction, and then you have the kind of the operation of the port, right? So it's different impacts. When you are building the port, the first thing you are going to do is to destroy the seabed, so you are going to put a lot of land under the water to just create an island, basically, that is going to be the all the filling of the port. And that's so bad for basically, all of the seagrass, all of the invertebrates, all of the animals that live by the coast. But then when it comes to the operation of the port, is when you have like, 1000s and 1000s of boats and ships coming every day and moving and if you think about this, as in the middle of the marine protected area, you have this port. You can imagine all of these port ships as like arrows and like going around and like disturbing the whales, polluting and, you know, just having a lot of impact on the environment, it's like, imagine you have, like a national park where you have 1000s of cars going everywhere, not only on the road, but outside of the roads. Will be really bad.

CURWOOD: Carlos, I think it's pretty clear that you put in exhaustive hours in this campaign. So now the question that I'm sure is on everyone's mind listening to us, to what extent does this story have a happy ending?

MOLINA: Yeah, I'm so happy that you are asking me for this question, because when the government changed their mind, and they were like, Okay, we are now against the port, and all of the Fonsalía platform, like all these citizen platforms, were so happy to celebrate that the port wasn't going to happen. Myself, along with my team and other partners, we continue working on, okay, this is not the end. We need to do something more. We need to really create something in this place to really have a happy ending. And this is where we started asking to Europe for funding to create a marine conservation and education center in the area where the port was going to be built. And two years ago, we got the announcement that Europe gave us the fundings. And this project is called Hope, and for many reasons, but of course, it's because it's bringing hope to this area, and it's very focused on working with the communities and being able to teach the communities about how important is this marine protected area that is connected to all of the Macaronesia. So now we are building this Marine Conservation Center, and I'm hoping that this is the real way to finish with the problem, a root problem of development and gentrification that is happening in the Canary Islands.

Tenerife is the biggest of Spain’s Canary Islands, hosting more than 5 million tourists a year. (Photo: Salvador Aznar)

CURWOOD: Anything more you want to tell us?

MOLINA: Yeah, hope is a very beautiful project, also because it's opening to Africa. So we have partners in Senegal, Ghana, São Tomé and Príncipe and in Cape Verde, and along with Portugal, so we are actually partnering this marine conservation center is in a network of other countries, and because there is so much work to do in conservation across the Macaronesia that is all of this region. So it brings a lot of hope to think about this.

CURWOOD: Of course, Tenerife is a vacation hotspot. So to what extent now does this area attract tourists in a sustainable way?

MOLINA: To be honest, we are very far from that. It's unfortunately, there is a lot of things to change in the Canary Islands, and especially in Tenerife, to change the way how tourism is dealing with the island every year only in Tenerife, that is an island of only like from side to side, is 120 kilometers. So it's not a big island. We have 6 million people visiting every year, which is a lot of people, most of them coming from not from Spain, but from Europe, from especially from England. And the problem is that there is we have promoted a lot of this cheap tourism when people are just coming to be in a hotel with the bracelet and they have everything inclusive, and they don't really engage with the communities, they don't learn about the culture. And this is a very big problem that is reflected in all of these hotels. In like, there is this place called Loro Parque that has orcas as an attractive for the tourists, and they are like living in a little aquarium, or there is a lot of golf course in places that are desert, that are using a lot of resources of the island that are necessary for the future. So, yeah, it's a it's definitely far from where it needs to be, but I can see that there is some changes going on, like the Fonsalía is one, a good example of it.

CURWOOD: What's your happiest moment these days now, when you come down to this area that was going to be a port and now is this conservation site that you call Hope, Esperanza. What do you think of most?

Carlos adjusted his career path by switching from civil engineer to a marine conservationist. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

MOLINA: You know, for me, the happiest moment for me is when I am under the water, so when I'm scuba diving, because that's my passion, and just being in the area where the port was going to be built, and being scuba diving there, and just thinking about it, it's just, it makes me break in tears every time I'm underwater. Under my mask, I am almost crying because it's so beautiful and it's so pristine and so amazing, that thinking that the humans can really make a good change for the environment and for the future is just it brings me a lot of happiness and hope.

CURWOOD: So what's next for you?

MOLINA: Yeah, well, I think I keep telling myself what is next is to not to give up in this world, because it's very hard, like at least three times a year I am about to give up, saying this is impossible, but I always keep going. So I think using this opportunity of the Goldman prize to go to the next level and be able to maybe start, I like to see that in the future, we are going to start projects in Africa and working with other countries and and use this model in the Canary Islands as standard that we can replicate in other places and and like create a ripple effect that really makes a difference for the ocean.

DOERING: That’s Carlos Mallo Molina, 2025 Goldman Prize recipient for Islands and Island Nations, speaking with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

Related links:

- Learn more about Innoceana and the work they’re doing

- Hear more about Carlos’s story

- Read about Carlos Mallo Molina and the Goldman Prize

[MUSIC: Nando Carneiro, “Peregrino” on A Windham Hill Sampler: Contemporary Instrumental Music From Brazil, by Nando Carneiro, Windham Hill Records]

Seagrass "Gardening"

Seagrass is a hidden gem responsible for large quantities of carbon absorption and fish production. (Photo: Frédéric Ducarme, Wikipedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O’NEILL: Well, Jenni, speaking of marine protected areas and seagrass, I think we ought to take a second to highlight just how cool this plant really is.

DOERING: Oh yeah, I mean for one it captures a lot of carbon, doesn’t it?

O’NEILL: Yes it does. I learned about this from Boze Hancock who is a marine restoration scientist with The Nature Conservancy and he explained to me that this is more than just seagrass using carbon dioxide to grow, like all plants do. It also slows down water flow, which allows the organic matter of the world to settle and accumulate on the ocean floor.

HANCOCK: Over time, there's a lot of material that gets buried because it's being caught by the seagrass bed and that contains a lot of carbon. So that's where your carbon sequestration comes from.

O’NEILL: And you might be surprised by just how much carbon this actually stores. We’re talking up to 35 times more carbon than tropical rainforests can store in the same period! Tropical rainforests!

DOERING: Wait a minute, seriously? I had no idea seagrass could have like THAT big of an impact on the carbon balance of the Earth.

O’NEILL: Right? I genuinely never would have guessed, and that’s why I was really glad to get this sort of lowdown from Boze Hancock. Balancing atmospheric carbon is only one part of the story. Seagrass is also a vital part of the near-shore ecosystem. So, kind of like the trees in a forest, it’s the structure that defines the entire ecosystem.

HANCOCK: That structure is what the fish need, what the small invertebrates need, what the food chain requires. It's why seagrass is one of our fish producing factories. Seagrass makes a lot of new fish for the environment, basically because the babies have somewhere to hide. So if you're a baby fish and you find a seagrass bed, you've actually found a nice safe house with a really well stocked fridge, and that bottom of the food chain then flows out through the fish, through the baby stages, into the larger fish and on.

DOERING: Aw, now I’m picturing little baby fish hiding in the seagrass just like Nemo in the amenomenome….

O’NEILL: Amnemmonemonene. An… anemonem… monemone! [AD LIB THIS]

It’s definitely pretty cute to think about. But sadly Jenni, as with so many of our stories, now we pivot. These baby fish and the seagrass are in hot water, though, because our greenhouse gas emissions are warming the planet. And you know the oceans have taken up a lot of that extra heat – as much as 90 percent! Boze told me that some spots close to home have it especially bad.

By placing plots of seagrass in warmer locations, scientists are figuring out which varieties can adapt to a changing environment. (Photo: NASA Kennedy Space Center, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

HANCOCK: In the Atlantic coast, particularly New England, temperatures are going up faster than they are on average, around the rest of the world. Our sea temperatures are going up nearly twice as fast as the average. So we've really seen an impact of increasing water temperatures in the near shore, and we're getting to the point now where we've reached the thermal limit for seagrass.

DOERING: Oh man. Much as I’d like warmer water for swimming, that doesn’t sound good.

O’NEILL: Definitely not, and it’s not just the heat that poses a threat – fertilizer runoff and ship anchors can hurt seagrass, too.

DOERING: Oh yeah. And you know, Carlos Molina, the Goldman Prize winner we just heard from, he also briefly touched on the fact that seagrass is very vulnerable to things like port construction. So given how important seagrass is, what’s to be done about all these threats?

O’NEILL: Well, were pivoting right back to the good-news part of this story. Boze Hancock and the team at the Nature Conservancy have this really cool project that they call “seagrass gardening.”

DOERING: Huh ok. Wait a minute, you’re not saying I can grow seagrass next to my tomatoes and garlic…

O’NEILL: Haha, Jenni I know you have a green thumb, but I’m not sure even you could pull that off. They call this the “common garden experiment” but I don’t believe your tomatoes and seagrasses have much in common. The idea is that we, as humans, can help cultivate seagrass just like a crop to help replace what’s being lost to ocean warming.

Rising sea temperatures are pushing seagrass further and further from the near shore. (Photo: Andrew Hill, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: Ok, so Aynsley, how does it work?

O’NEILL: Well, Jenni, as far as I can tell it takes a little more patience than waiting for zucchini to ripen. Granted, I’ve never waiting for zucchini to ripen other than in my fridge. But, I still think that it’s a little trickier because this is all trial and error. They take patches of seagrass from different regions and microclimates and they transport them to warmer waters to see which ones adapt and survive. And then they repeat that process over and over and over again.

DOERING: Huh! So it sounds like survival of the fittest. And I think scientists restoring corals are doing something similar. So what has all this careful selection led to?

O’NEILL: Well, Boze tells me that the more resilient types of seagrass, which are from slightly warmer regions, are really starting to take off when they’re planted in spots where the local seagrass has died off.

HANCOCK: There are some fantastic examples of where seagrass restoration has been spectacularly successful. The Virginia Coast reserve on the Atlantic side of the Delmarva Peninsula is probably the best seagrass restoration project on the planet at this point. We've gone from zero seagrass in that system of lagoons between the Delmarva Peninsula and the barrier islands to, last time I looked at it, we were over 10,000 acres. Really successful.

DOERING: Huh! I have to admit, I’m a little squeamish about seagrass tickling my feet when I’m swimming at the beach, but it does sounds like it’s something to celebrate!

O’NEILL: There is something to celebrate, so I vote that we push all that blame onto seaweed instead. It’s completely different but definitely still slimy. Because yes, the seagrass garden is a win for conservation! With the work that Boze Hancock and other scientists are doing to help these seagrasses thrive in a warming world, I have some hope that seagrass won’t be going anywhere anytime soon.

Related links:

- Learn more about the link between seagrass and carbon emissions.

- The Revelator | "Seagrass Gardening"

- The Nature Conservancy

[MUSIC: The Shady Ukulele Band, “Sunrise” on Hawaiian Ukelele Hits, 2014 Exit Code]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Daniela Faria (like Maria), Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Frankie Pelletier [pella-TIER], Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

O’NEILL: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram at living on earth radio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth