February 10, 2023

Air Date: February 10, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Great Salt Lake Going Dry

View the page for this story

Since 1860 the Great Salt Lake has lost three-quarters of its water, mostly due to human activities, and some scientists now predict it will dry up completely in the next five years unless emergency conservation measures are taken. The loss of the lake would devastate migratory bird populations and create a public health crisis linked to toxic dust in the lakebed. Brigham Young University ecologist Benjamin Abbott spoke with Host Jenni Doering about the crisis and why water conservation in the agricultural sector is vital. (09:45)

Environment & President Biden's State of the Union

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Though it was not the central theme of his 2023 State of the Union speech, President Biden devoted more time to the environment than previous presidents have in this annual ritual. Commentator Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss President Biden's mentions of climate investments across the United States and an initiative to replace lead pipes that drew bipartisan applause. For history they talk about Lyndon B. Johnson, the first US President to mention climate change in a written addendum to a State of the Union speech. (07:39)

Red Tape for Green Buses

View the page for this story

To replace polluting diesel school buses with clean electric ones the bipartisan infrastructure law signed by President Biden in 2021 allotted $5 billion over five years for low-income communities. But an unintended consequence of the measure’s terms prevents some of the neediest communities from benefiting from the program. Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky (IL-09) joins Host Steve Curwood from Washington, D.C. to explain what changes she and other lawmakers are calling for. (06:42)

Recycling and Unhoused Californians

/ Isabella ZavariseView the page for this story

The California recycling system depends heavily on the informal labor of unhoused residents who collect recyclables and bring them to recycling centers. But many unhoused people say the state has rarely engaged with them and can even make it more difficult for them to do their work. Reporter Isabella Zavarise digs into the story for Living on Earth. (07:27)

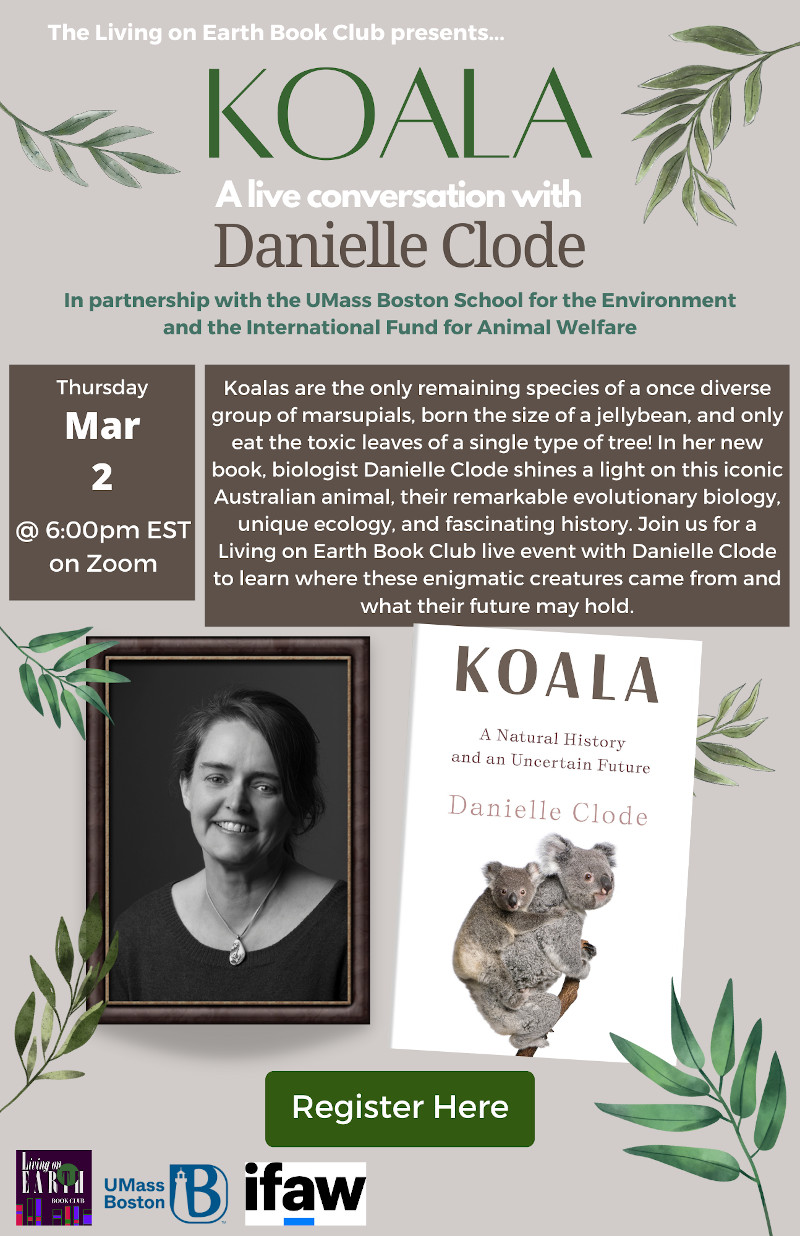

The Next Chapter of the Living on Earth Book Club

The cuddly Koala is one of the most charismatic and beloved species on Earth, but massive wildfires and habitat loss threaten their very existence. Tune in on March 2nd as we talk with award-winning Australian author Danielle Clode about her new book “Koala: A Natural History and an Uncertain Future", which takes us on a journey up into the trees to discover the remarkable physiology and ecology of koalas. ()

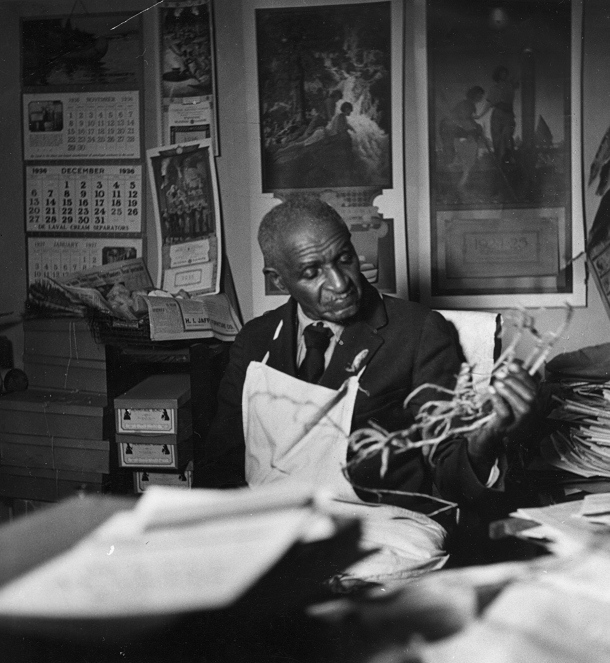

Black History: George Washington Carver

View the page for this story

George Washington Carver was born into slavery but went on to become a famous agronomist and helped poor people in the South improve their lives and soils by planting peanuts and other legumes. This week, he comes back from the past in the form of actor and playwright Paxton Williams. As “George Washington Carver” Williams talks to host Steve Curwood about the future of modern-day agriculture and intersections between racial dynamics and agricultural development. (14:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230210 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Benjamin Abbott, Jan Schakowsky, Paxton Williams

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Isabella Zavarise

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The Great Salt Lake in Utah could dry up in five years if nothing is done.

ABBOTT: If we lose the lake, we are going to see hemispheric ripples that go through not just the Utah Nevada region but all throughout North and South America with these bird species that are travelling to those regions.

CURWOOD: Also, unhoused people in California are the backbone of the state’s recycling program but say they get little support or respect.

TSCHAPPATT: I deal with trash all day, every day. I only hold what I know has a value to it. It's free money. Why wouldn't you want to get it? People see us and they're like ‘Oh they’re homeless? Like damn we know how they are. They're going to pollute everything.’ As you can see, I keep it clean, as clean as I can.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Great Salt Lake Going Dry

A new report found that the Great Salt Lake will disappear in 5 years if water consumption isn't cut almost in half in the next two years. (Photo: Jan Arendtsz. Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

When European explorers found the Great Salt Lake in what is now Utah, they encountered the largest inland saltwater body in the Western Hemisphere and the eighth largest in the world. But since 1860 the Great Salt Lake has lost three quarters of its water and some scientists now predict it will dry up completely in the next five years if nothing is done. Part of the problem is the climate disruption that is driving a water crisis across the American west, with Lakes Mead and Powell along the Colorado river also at record lows. But scientists say human overuse is a more important threat to the future of the Great Salt Lake. Benjamin Abbott is an ecologist at Brigham Young University in Provo Utah and co-author of a recent study that calls for emergency action. Professor, welcome to Living on Earth!

ABBOTT: Thank you so much, Jenni.

DOERING: So what is happening to the Great Salt Lake?

ABBOTT: For over 100 years, we've been using too much water in great salt lakes watershed, and the lake level has been gradually declining. But what we've seen over the past few years is the lake level has really taken a nosedive, and we've been losing 1.2 million acre feet of water a year. If we continue to lose water at the rate that we are, then we're looking at a five year timeline before the lake as we know it, doesn't exist anymore.

DOERING: So what would that mean for the people, the animals ecosystem of the Great Salt Lake region? What would a collapse really look like?

ABBOTT: Great Salt Lake is what we call a keystone ecosystem. It holds up and supports so many ecosystem services for society, and also inherent environmental processes. Great Salt Lake is the largest saline lake in North America. And it exists right in the middle of the Great Basin. So it's this giant area covers a big portion of Utah and Nevada, little bit of the state's around that doesn't drain to the ocean at all drains down into the salty lakes. It's about 98% land. So every little fragment of aquatic habitat is really important for local wildlife. Also, for migratory birds, this is part of the Pacific Flyway and 10 million migratory birds, about 350 species of birds depend on Great Salt Lake at different parts of their lifecycle. And that's just one of the dimensions kind of the environmental side, if we lose the lake, we're going to see hemispheric ripples that go through not just the Utah Nevada region, but all throughout North and South America with these bird species that are traveling to those regions. There's a more dire and direct impact that we would see. Because these saline lakes are like bathtubs, they're all draining down to the bottom through time, they accumulate a lot of both natural and human created pollutants, things like heavy metals and Cyanotoxins, herbicides, pesticides. But as these lakes shrink, then that sediment is exposed, and those pollutants can become airborne. And we've already begun to see an increase in these toxic dust storms from Salt Lake and the surrounding drying out Lake basins.

A recent report from nearly three dozen scientists and conservationists found the lake is now 19 feet below its natural average level and has lost 73 percent of its water amid excessive water use and a worsening climate crisis. (Photo: Kari Nousiainen, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

DOERING: What is on the other side of the equation, you know, the economic value of taking the water from the lake?

ABBOTT: The lake directly supports around $2.5 billion a year of economic activity. That's primarily mineral extraction from the lake. Great Salt Lake is the only source of magnesium in the United States, the lake is a very large tourist draw. And so you have people from around the world who are coming to experience this unique ecosystem.

DOERING: So what are the biggest reasons for the great salt lakes disappearance right now?

ABBOTT: There's a pretty clear dominant cause about 80% of the loss of water is being caused by irrigated agriculture. These are freshwater streams and rivers that would naturally flow to the lake. And we're diverting that water using it to grow especially alfalfa, but other crops as well, that's 80% of the problem. Now, between five and 15% of the issue is also climate change, right. These long term warmer and drier conditions that have set up that reduce the natural amount of water, and then the remaining 10% is that industrial extraction of water from the lake and urban water use. So this is really fundamentally different than some other areas, right? You might have heard about the situation in Las Vegas, where really, they're crunched, they don't have water for people to drink. So you have to recycle the water, or South Africa, where Johannesburg literally has to turn off the municipal water supply. It's not a story of people brushing their teeth for too long or taking too many showers. This is all about outdoor water use. From the beginning we've over allocated the water resources. And throughout the 20th century in the western US, we had this obsession with these large water projects. And that created artificially subsidized water that then encouraged growth of types of agriculture that really have no business existing in this region.

Important coverage by @BillWeirCNN on the drying of Great Salt Lake.

— Ben Abbott (@thermokarst) February 10, 2023

As Dr. Bonnie Baxter says, “This is an ecological disaster that will become a human health disaster...We see a crisis that is imminent.”

Let's #growtheflow to #GSL

https://t.co/p0koeFcVNg.

DOERING: So, what are some of those options that could keep this agricultural economy alive without using nearly as much water as they are now?

ABBOTT: One of the best options is actually keep growing the crops that you're growing, just do it more efficiently. And alfalfa is a great example. This is a crop that is a multi-year crop. You can actually keep growing alfalfa keep growing the other crops that you're growing, just do it better. This is called agricultural optimization, transition from flood irrigation, which is the most common type of irrigation in the watershed right now. Transition to sprinklers and then with alfalfa, it's quite flexible where let's just do one or two cuttings instead of three or four, and we could very easily see 50, 60, 70% reduction in the amount of water being used for those crops while still allowing and supporting this agricultural part of the economy and identity here.

DOERING: Why are farmers not already adopting some of those practices like, you know, one, two cuttings instead of three or four that you say could maybe save a lot of water?

ABBOTT: It's very easy to say, I can't believe that these farmers are doing these things. But we need to take a look at what the law is what the incentives are. And literally until just a few months ago, Utah had a use it or lose it water law, this is very typical for states in the West. So if you have a water right to, let's say, 1000 acre feet of water, you don't need all of that water to grow your crops, maybe it was a wetter year, or maybe you don't have all of your fields in cultivation. Well, if you don't use it all, then that water can be taken and allocated to someone else. Thankfully, the legislature changed that law. And it is now is possible to say, okay, I'm only going to use what I need, and then I'm going to designate the rest for they call it environmental flows, you no longer risk losing that water. In fact, you can even be paid for that water right that you're allowing to go to Great Salt Lake. And so, this is not an issue of the ignorant farmers or the uncaring farmers, this was a system that really discouraged conservation. Things that we're calling for in our report is, let's send out water educators, ambassadors, lawyers to every corner of the watershed so that every farmer knows what resources are available for agricultural optimization, and that they have the support, the financial and legal support they need to make those changes.

The lake and its wetlands provide minerals for Utah’s industries, thousands of local jobs, and habitat for 10 million migratory birds. (Photo: Stephanie Young Merzel, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: What are some of the ways that the Utah State government can help remedy this situation that's happening in the Great Salt Lake?

ABBOTT: I think we need two kinds of action. We need legislative change that's going to encourage long term conservation finally bring our demand in line with what the environment here can support. Some of that has already been passed, the 2022 legislative session was called the year of water. However, most of those efforts are going to take multiple years, maybe even a decade or two to bear fruit, you know, before they start returning water to the lake and we simply don't have that much time. We need emergency releases of water from reservoirs in Utah. No one has succeeded in stopping or at least restoring these saline lakes systems when they start to decline. Looking at the Aral Sea, Lake Urmia, Owens Lake, Mono Lake, Lake Chad, right, you can go across all the continents success looks like maybe slowing the rate of decline, or in some edge cases stopping it for a period of time.

DOERING: How optimistic are you that things can turn around for the Great Salt Lake?

ABBOTT: The number one thing that makes me optimistic maybe sounds strange, but we've been wasting a lot of water. If you look at the per capita water use in Utah, it's very high. And if you compare it to other dry regions on the planet, we use almost seven times more water per person than the country of Israel does. And so that actually gives us a lot of room for improvement. With some pretty common-sense changes, we can get the kind of conservation we need. We estimate, looking at the lake’s hydrology over the past few decades that we need to reduce water use by 30 to 50% per capita, we're not talking about minor changes, but our agricultural water use, or outdoor urban water use, has been so inefficient in the past that we can do that easy. We can meet those targets. I really believe we can do it; it still is going to be tight. We don't have much buffer left; the lake is almost dry. And so, we've got to do this fast. But as far as is it even technically possible or feasible, resoundingly yes. There's no question. We could do this if we focus, if we bring the resources to bear that we need.

DOERING: Ben Abbott is an ecology professor at Brigham Young University. Thank you so much, Ben.

ABBOTT: Thank you so much, Jenny for bringing attention to this important issue.

Related links:

- BYU College of Life Sciences | “Emergency Measures Needed to Rescue Great Salt Lake from Ongoing Collapse”

- The Guardian | “‘Last Nail in the Coffin’: Utah’s Great Salt Lake on Verge of Collapse”

[MUSIC: Cannonball Adderley, “One For Daddy-O – Remastered” on Somethin’ Else (Rudy Van Gelder Edition), Blue Note Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up –the new law intended to give poor communities access to non-polluting electric school buses is actually blocking access in some cases. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Cannonball Adderley, “One For Daddy-O – Remastered” on Somethin’ Else (Rudy Van Gelder Edition), Blue Note Records]

Environment & President Biden's State of the Union

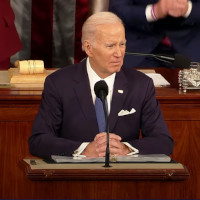

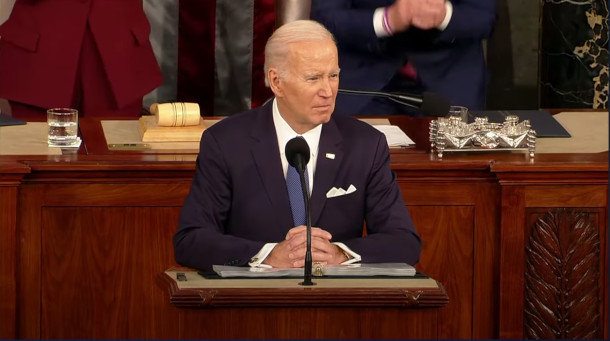

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr., the 46th and current President of the United States and member of the Democratic Party during the State of the Union Address on February 7, 2023. (Photo Screenshot of White House Video, Fair Use)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

And on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is living on Earth commentator Peter Dykstra to take a look Beyond the Headlines. And, Peter, I think most of the things we talk about on this show were, in fact beyond the headlines a few days ago when the President gave his State of the Union speech.

DYKSTRA: Well Steve, CNN did an interesting thing and they took a stopwatch to the amount of time that President Biden spoke on each of the pressing issues of the day, inflation and the economy and jobs and infrastructure and Ukraine. Climate came in 10th place among those issues, for a grand total of about two minutes worth of discussion.

CURWOOD: That's right, although it's more than we've heard from other presidents in other State of the Union speeches about the environment. Let's take a listen to that section of his speech.

BIDEN: The inflation Reduction Act is also the most significant investment ever in climate change, ever. Lowering utility bills, training American job, leading the world to a clean energy future. I visited the devastating aftermath of record floods, droughts, storms and wildfires from Arizona, New Mexico to all the way up to the Canadian border. More timber has been burned and I've observed from helicopters then the entire state of Missouri and we don't have global warming, not a problem. In addition to emergency recovery from Puerto Rico to Florida to Idaho, we're rebuilding for the long term. New electric grids that are able to weather major storms and not prevent those fire forest fires, roads and water system withstand the next big flood, clean energy to cut pollution and create jobs and communities often left behind. We're gonna build 500,000 electric vehicle charging stations installed across the country by 10s of 1000s IBEW workers. And helping families save more than $1,000 a year with tax credits, to purchase electric vehicles in efficient, efficient appliances, energy efficient appliances. Historic conservation efforts to be responsible stewards of our land, let's face reality. The climate crisis doesn't care if you're in a red or blue state, it's an existential threat. We have an obligation not to ourselves but to our children and grandchildren to confront it. And I'm proud of how, how America at last is stepping up to the challenge. We're still gonna need oil and gas for a while. But guess what? No we do…But there's so much more to do. We got to finish the job. We pay for these investments our future by finally making the wealthiest and biggest corporations begin to pay their fair share. Just begin.

During his second State of the Union speech President Biden mentioned the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law signed in November of 2021 that is meant to fund a national network of electric vehicle charging stations and allocate $7 billion to support the U.S. battery supply chain. (Photo: Ivan Radic. Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, it's unusual for a president to go after the oil industry. One exception was back in 2006, when George W. Bush looked at America and Congress and said, we're addicted to oil. Nothing really happened with the oil industry after that. Let's see what happens now with Joe Biden, pledging what sounds like a royal fight over climate change. And not to mention not paying any taxes or very little.

CURWOOD: Yeah, looking oil straight in the eye is I think something of a first here.

DYKSTRA: One of the big issues that was not mentioned that is maybe a lost opportunity is we're looking at a huge and possibly never ending battle to limit plastics in the environment, everywhere from oceans, to atmosphere, to soil, to our own bodies. And of course, plastics are another part of the fossil fuel industry, which even if oil and gas aren't curtailed, that's still part of the petrochemical industry. That's maybe a safety valve for oil and gas to continue. It's a petrochemical product, one of the biggest ones and new oil and gas facilities are being built and structured just to make more plastic.

In his State of the Union address, Pres. Biden reminded lawmakers that ‘the climate crisis doesn’t't care if your state is red or blue. It is an existential threat.’

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) February 9, 2023

While discussing the Inflation Reduction Act, Biden also broke down how the U.S. is preparing for future disasters. pic.twitter.com/ydla6X4IBk

CURWOOD: That's right. He didn't address the plastic debt that we are building up and literally Peter right, because just about every week we ingest a credit cards worth of plastics into our bodies.

DYKSTRA: That's right and that's an appalling thought brought to us by research in the past year or so.

CURWOOD: There were other things that he said though, Peter, what did you notice?

DYKSTRA: Well, talking about lead in drinking water from aging lead pipes, as part of infrastructure, getting rid of all those pipes, mostly in poor urban areas, is something that even speaker Kevin McCarthy seated behind the president along with the Vice President Harris, even Kevin McCarthy applauded that. He obviously didn't applaud a whole lot of other things. But also a few things that maybe there was an opportunity to at least acknowledge and mention, there has been an effort underway by Republicans to gut regulations, including laws like the Endangered Species Act. He could have mentioned more about environmental values in general. But we ended up with those two minutes. And by State of the Union standards, that's a lot.

President Biden speaking of the State of the Union. (Photo Screenshot of White House Video, Fair Use)

CURWOOD: I agree. You know, Peter, there was one thing that in the run up to that speech on February 7th that I found it disturbing. The many major news outlets said the polls show that the President is underwater with the American public, and that he'd have a tough time with this speech. But as I recall, last fall, during the elections, they said that there was going to be this huge red wave. Why should we keep believing these polls that these major news organizations keep trying to sell us?

DYKSTRA: Well, Steve, you're right about the big red wave being a major blunder by pollsters and pundits in the midterm elections. Go back a few years farther to 2016, all of the polls and all of the pundits told us there was no way that America would make Donald Trump its next president.

CURWOOD: I certainly do remember that. Hey, Peter, before you go take a look back in history for us.

President Lyndon B. Johnson (Photo: Library of Congress, Unsplash, public domain)

DYKSTRA: February 8, 1965 that's 58 years ago, in a special message to Congress, which was a written addendum to his State of the Union speech, President Lyndon B. Johnson became the first president to make reference to climate change. He said, quote, "This generation has altered the composition of the atmosphere on a global scale, radioactive materials and a steady increase in carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels.” LBJ said that 58 years ago, and we're still mostly in the talking phase about it.

CURWOOD: What an interesting President, Peter looking back. Lyndon Baines Johnson of course lost his reputation in the Vietnam War, but gave us the Civil Rights Act and was prescient about climate disruption. Who knew... Thanks, Peter, Peter Dykstra is a commentator with living on Earth. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Steve. It's been a pleasure. We'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth web page that's loe dot org.

Related links:

- Watch President Biden's State of the Union Address

- Read President Biden’s State of the Union Speech

- CNN | “Fact-Checking President Biden’s State of the Union Speech”

- LBJ’s climate remarks recalled by “Climate Science, 50 Years Later” in Physics Today

[MUSIC: Hank Mobley, “Dig Dis – Remastered 1999/Rudy Van Gelder Edition” on Soul Station, Blue Note Records]

Red Tape for Green Buses

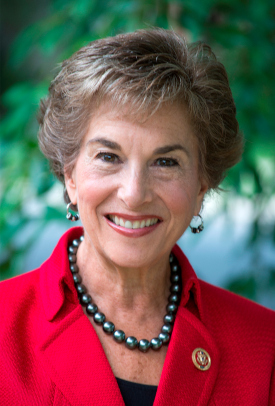

The EPA has begun a Clean School Bus Program that low-income communities across the country are able to apply for, but there’s a catch: some school districts are unable to fulfill the scrappage requirement. (Photo: Caitlin Looby, UCI Sustainability, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Under the bipartisan infrastructure law signed by President Biden the Environmental Protection Agency was allocated $5 billion over five years for low-income communities to replace polluting diesel school busses with clean-energy ones. But as the electric bus program is starting to roll out, critics say the EPA’s definition of low-income school districts prevents some needy communities from benefiting. The law also requires that grantees must scrap their old diesel buses. But since many of these low-income school districts outsource their transportation and don’t directly own buses, they are ineligible for this program that is supposed to help communities often disproportionately exposed to unhealthy air to begin with. Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky represents the 9th district of Illinois and she joins us now from Washington. Congresswoman, welcome to Living on Earth.

SCHAKOWSKY: Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: Now, Congresswoman, I understand that you and a group of other Illinois lawmakers have written to the Environmental Protection Agency urging them to revise their scrappage requirements. What does that rule ask? And what, if anything, have you heard back from the EPA on the matter?

SCHAKOWSKY: Well, there's a couple of problems with actually implementing what is really a good idea. For one thing, it requires by law, that you trade in the diesel bus that you've been using for an efficient piece of equipment. But some of the school districts actually don't own their own school buses, and they rent from companies that do, and they are not in a position to make the swap. So that is one of the problems. One of the other ones for us in Illinois and in Chicago, and Senator Durbin and I are concerned about it, that rightfully so, the money has to go to more lower-income districts. But the city of Chicago, because it's counted as just one district does not qualify, not any of the neighborhoods in the city of Chicago qualify, because if you average it out, we don't meet the requirements. But we would like to see the idea that lower-income school districts that are using the diesel fuel are able still to be eligible. And we'd like to see a change in the EPA. But so far, we haven't seen it.

CURWOOD: So as I understand it, then the EPA has little flexibility to deal with this situation. They're looking at the law, the way the law is written. And to what extent might they be able to somehow accommodate?

The toxic soot including PM2.5 particulates from diesel fumes are linked to various cardiovascular diseases and respiratory conditions, such as asthma and COPD. (Photo: MPCA Photos, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

SCHAKOWSKY: Well, it's not such a crazy idea to say that we adjust the law to accomplish the goals that we really want to accomplish. That's the problem. It's standing in the way of the intention of this program, to make our children safer on the bus. And so if there is this flaw, in the way that the law is written, that prohibits the most eligible of our children to have electric buses, then we need to change the law. I think the pressure is going to have to come from governors, from mayors, from residents, from ordinary people, who say I want my kids to be able to have safe travel to and from schools. And we're going to just have to organize around this. So I know that we've got senators as well as representatives on our team to be able to make this law workable for the communities that need them most. You know, the $5 billion over five years, is a pretty sparse investment, and making sure that the transportation for our kids is adequate, I think it's, you know, it's an okay start. But we have to make sure that they are number one on the list, and that we are investing as much money as it's going to take to make all communities safer. I think it's good that we are focusing more on the low-income communities. But there are middle level communities right now that aren't able to get that support. We need to do better.

CURWOOD: So what happened in the drafting of this law that got us into this situation, in your view? To what extent were people not paying attention? To what extent was there a last minute compromise by folks who understood maybe this would cut out poor communities? Why do you think this happened?

SCHAKOWSKY: Oops! I do think that the idea of a swap, okay, we will give you electric school buses, if you get rid of the diesel ones; not really understanding, I think, or foreseeing that this was not going to be possible in a number of communities. That's why I think it ought to be really a pretty easy fix to make the change. I think it was just not really foreseen that this was going to be a huge issue.

CURWOOD: You're now at the beginning of your 13th term on Capitol Hill, you've been there a couple of decades plus. So as someone who has survived and thrived in that environment, what's the next move for you to get this settled?

US Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) is in her thirteenth term. (Photo: Jan Schakowsky, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

SCHAKOWSKY: Look, I do believe that there is growing concern about these environmental issues, about the health consequences of the bad environment that all of us are living in, the costs that we incur because of health care if we don't do these things right. I don't see it as a partisan issue. I do think that these kinds of things, especially when it deals with children, we ought to be able to make progress. As divided as it looks right now, often when it comes to the committee work, when you get down to the work on individual issues, we're going to be able to get things passed on a bipartisan way. And certainly with a higher understanding of the importance of the health care costs that are created, because of the bad environment, because of the pollution, because of the diesel fuel, I am hoping that we're going to be able to move ahead and make a difference.

CURWOOD: Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky is serving her 13th term representing Illinois ninth district. Congresswoman, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

SCHAKOWSKY: Well, thank you, I appreciate it.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “The EPA Is Helping School Districts Purchase Clean-Energy School Buses, But Some Districts Have Been Blocked from Participating”

- Congresswoman Schakowsky’s Official Website | “Schakowsky, Durbin, Chicago Delegation Urge EPA to Expand Eligibility Guidelines for Clean School Bus Program”

- Learn more about the EPA’s Clean School Bus Program

[MUSIC: Trampled By Turtles, “School Bus Driver” on Songs from a Ghost Town, Banjodad Records]

Recycling and Unhoused Californians

Seen here with his dog, Timothy Tschappatt is an unhoused California resident who spends 12 hours a day finding recyclables and bringing them to recycling centers to earn money. (Photo: Isabella Zavarise)

DOERING: California has one of the best recycling rates in the country. Consumers pay between 5 and 10 cents extra for most beverages with the expectation that the containers will be returned for the deposit and get recycled. But that system depends heavily on the informal labor of unhoused residents who scour the streets for recyclables and bring them to recycling centers. The workers make some money and keep the streets cleaner, a win- win. But many unhoused people say the state has rarely engaged with them and can even make it more difficult for them to do their work. Reporter Isabella Zavarise has been digging into the story for us.

[FREEWAY NOISE]

TSCHAPPATT: When we go through the trash it’s unlimited. The only thing I have not found is a submarine, a jet and a rocket.

ZAVARISE: Timothy Tschappatt, dressed in a basketball jersey, is a friendly, personable guy. His two small dogs run around him as he excitedly points to the tidy piles of items surrounding his home. He started collecting recyclables with his brother when he turned 16 for some money. He’s now 44, and has been unhoused for almost half his life. Tschappatt says his path to homelessness started when he was in prison. He lost everything, including family members who died during his 5-year sentence.

Now, he lives here, next to the 101 freeway, with his girlfriend. A few months ago, they woke up to Caltrans, the state’s transportation agency, rummaging through their encampment without warning. The agency tore through their belongings, not only leaving a mess for them to clean, but also taking recyclables they spent weeks collecting. Tschappatt says this isn’t the first time.

TSCHAPPATT: They mess our business up all the time. We are actually at least trying to get out of here, like straight up. We don't want to be here, to tell you the truth.

ZAVARISE: The Department of Transportation is supposed to provide 72 hours notice when they conduct these sweeps. Sometimes the couple has received these notices. Sometimes they haven’t. Michael Comeaux is a public information officer with Caltrans.

COMEAUX: The crew is not there to sort recyclables. The crew is there to remove trash and junk. The owners of any materials that are being stored along state highway right of way have that 72 hour period to remove anything that they want, and if material is left there, it's assumed to be trash.

Mr. Tschappatt says that Caltrans sometimes picks up collected recyclables from encampments without warning, mistakenly classifying the items as trash. This takes away potential income from Mr. Tschappatt and scavengers like him. (Photo: Isabella Zavarise)

ZAVARISE: Hearing that the items Tschappatt collects end up in the trash is a blow to him. Working 12-hour days rummaging through bins to earn a few hundred dollars is difficult and tedious work.

TSCHAPPATT: Oh, man, that makes my eyes so watery because I was like damn. Granted, that's money that we have found, but the time, effort, energy, everything, our youth. Everything is going down because of that, you know?

ZAVARISE: As of 2020, California’s homeless population was around 161,000 - the majority of which live in Los Angeles. Lack of support for Tschappatt, and the unhoused community more broadly, is a major flaw in California’s recycling system which depends on the informal labor of thousands of people. Unhoused people aren’t the only ones engaging in this work. Low-income families and gig-workers also help keep it going. The state’s recycling rate is around 70%, down from 75% in 2019; a number that keeps falling as recycling centers close.

Tri-CED community recycling is one of California's largest nonprofit recycling operations. Richard Valle is the president. He says the company pays anywhere from $17,000 to $22,000 in cash daily and sees up to 400 customers per day — most of whom are unhoused.

VALLE: People who take the time to stand in line and get cash for recyclables are not going to put it at the curbside because they want that return on investment. Therefore, the majority of the people who are in those lines need the cash. It supplements their income. It's just that simple.

The California recycling system relies heavily on the informal labor of scavengers like Timothy Tschappatt, who keep recyclables out of landfills. (Photo: Isabella Zavarise)

ZAVARISE: A bounty on bottles and cans drives recycling rates, but in L.A. County there are just under 400 recycling centers left. Many of these centers have closed in the last few years due to decreasing aluminum prices and high operating costs. Recently, Governor Gavin Newsom promised to invest $220 million dollars into recycling centers. These businesses are important because recycling centers are one of the few places that pay for recyclables and few grocery stores will take these items.

Recycling has become so difficult for some that last year, Tschappatt started a business to handle recycling for people who don’t know how to navigate the system. It’s called Recycling Junk Kings. He refurbishes items, declutters garages, and strips gold and copper out of discarded electronics. People also drop off items in front of his tent near the freeway to return to recycling centers. Tschappatt doesn’t own a car. He uses a luggage cart to push the recyclables up a steep hill until he gets to the closest center.

TSCHAPPATT: I deal with trash all day, every day. I only hold what I know has a value to it. It's free money. Why wouldn't you want to get it? People see us and they're like ‘Oh they’re homeless? Like damn we know how they are. They're going to pollute everything.’ As you can see, I keep it clean, as clean as I can.

ZAVARISE: There is no clear measurement of how much people that engage in the informal recycling economy prevent from winding up in landfills. One study from 2002 found that salvagers in Santa Barbara brought in nearly a third of the total weight of material being recycled. CalRecycle doesn’t track who redeems containers and if they have an address or not. They do know that most people bring in far more recycling than they could actually produce themselves, suggesting that they collected the bulk of the material. Despite all of the work unhoused people do to keep beverage containers out of landfills, they’ve never been included in the decision making process, says Scott Smithline, a previous director of CalRecycle.

Despite the role they play in the recycling system, unhoused people have rarely been included in the decision-making process. (Photo: Isabella Zavarise)

SMITHLINE: If I’m being honest, I just had like a little emotional experience where I realized that, you know, in my tenure at the department I didn't make any effort to reach out to the unhoused community. You know, we sort of applauded ourselves to try and bring our public meetings and to bring our recycling programs to as many diverse communities as possible. But if I'm being honest, I can't recall ever directly reaching out to the unhoused community representatives and asking them to join us in those conversations. I consider myself to be a fairly open minded guy. And the fact that I didn't even make that happen, probably tells you that there's a lot of work that needs to be done.

ZAVARISE: Smithline acknowledges the failures CalRecycle has made in engaging the unhoused community. And after years of struggling with the government, Timothy Tschappatt is skeptical of working with them.

TSCHAPPATT: Let me tell you the truth on that. Say we did do something like that. Like, they would never pay attention to those ideas. They would say they brought it up themselves. Plain and simple, they would not give the credit where credit is due period and the people would just keep struggling.

ZAVARISE: For now, California doesn’t have plans to include unhoused people in its recycling efforts. Though they might look to cities like Vancouver, Canada where local businesses hire people to sort their recyclables. It’s honest work that keeps waste out of the environment, helps recycling centers stay open and combats the stigma associated with informal trash collection.

For Living on Earth, I’m Isabella Zavarise in Los Angeles.

Related links:

- CalRecycle

- Tri-CED Community Recycling

- California Department of Transportation

- CalMatters | “California Accounts For 30% of the Nation’s Homeless, Feds Say”

[MUSIC: khoa, Paul Grant, “Passenger” Single, Radio Juicy]

The Next Chapter of the Living on Earth Book Club

DOERING: The cuddly Koala is one of the most charismatic and beloved species on Earth. But massive wildfires and habitat loss threaten their very existence. In her new book “Koala: A Natural History and an Uncertain Future", award-winning Australian author Danielle Clode takes us on a journey up into the trees to discover the remarkable physiology and ecology of koalas. She joins us for the next Living on Earth Book Club livestream on March 2nd at 6 o’clock Eastern, and you’re invited! For details and to register for this free event go to loe.org/events.

Related links:

- Find out more and register for this upcoming live event

- Purchase a copy of Koala: A Natural History and an Uncertain Future (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

CURWOOD: Coming up – In honor of Black History Month we’ll have a visit with agricultural genius George Washington Carver. You can hear him just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Hank Mobley, “Dig Dis – Remastered 1999/Rudy Van Gelder Edition” on Soul Station, Blue Note Records]

[MUSIC: Caratini Jazz Ensemble, “West End Blues” on Darling Nellie Gray (Variations sur la musique de Louis Armstrong), Label Bleu]

DOERING: PFAS chemicals are linked to reduced fertility, metabolic disorders, and cancers. And researchers recently found concentrations of the forever chemicals are especially high in freshwater fish, including varieties eaten by people.

ANDREWS: We actually made a comparison showing that consuming a single fish serving, and these are freshwater wild caught or locally caught fish, would be equivalent to drinking over a month of contaminated drinking water.

DOERING: We’ll have some tips for how to eat fish safely, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Caratini Jazz Ensemble, “West End Blues” on Darling Nellie Gray (Variations sur la musique de Louis Armstrong), Label Bleu]

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

[RADIO STATIC]

Black History: George Washington Carver

Soil scientist George Washington Carver lived from 1864 to 1943 and began working at the Tuskegee Institute in 1896. His reputation rose to fame during the early 1920s. (Photo: National Archives and Records Administration, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Dr. George Washington Carver born a year before the abolition of slavery is remembered as a legendary champion of sustainable farming. Cotton had ravaged the land when he arrived in Alabama to direct the Tuskegee Institute's Department of Agriculture. But with his benevolent attitude and profound religious faith, Carver devoted his time to projects that encouraged farmers to plant soybeans and peanuts to restore the soil. He developed over 300 derivative products from peanuts to expand the commercial market and he educated poor farmers. This Black History Month, we honor his life's work.

WILLIAMS: Hello, hello. How are you doing today?

CURWOOD; What– What's that? Am I hearing something? Dr. Carver?

WILLIAMS: Yes, sir. It is me.

CURWOOD: Wow, how are you here?

WILLIAMS: I like to return from time to time to see how things are going, and I figured I'd spend a little time with you now.

CURWOOD: That's the magic of radio, I guess. This is such a great honor. What was it like in your time to be a pioneering figure and, and a black man in the agricultural field? I mean, how much was this a natural step forward from your childhood love for plants and animals?

WILLIAMS: Let me begin by saying I really appreciate that question. You see, the majority of my life, I've always been doing the same things. When I was a little boy growing up in southwest Missouri, I tried to explore my imagination. I tried to be creative. I tried to find ways to help people. And as I grew older, I learned that I could do that with science and agriculture and farming and, and working with folks. And so the work that I've done, for the majority of the time, I've been here at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, I've really been doing the same thing. I've been working with folks, I've been finding ways to bring people together. And it's all been a continuation of something that I started a long, long time ago.

CURWOOD: I see. Now Dr. Carver, when you just graduated and started your work, there was no great conservation movement like we have in the United States here today. So tell me, what did conservation mean to you? And and how did other people around you view your work at this time?

WILLIAMS: Conservation meant to me what it means to me now. It means to put things to good use. To not waste. I first graduated with my bachelor's degree in 1894. I wasn't exactly certain what I want to do. But the folks there asked me to stick around. And then in 1896, I received a letter from Mr. Booker T. Washington, asking me to come teach at the Tuskegee Institute. That ideas I learned about farming and agriculture, I knew that many of the folks in the south could benefit from. I have always said, where the land is poor, the people are poor. And I knew that if we could find ways to increase the health of the soil, we can increase the health and living conditions of the farmers there. I sought to find ways to add more nutrients to the soil. I tried to come up with creative ways to use different farm byproducts. There are many uses if we use our creativity, we can find many uses for things that heretofore we hadn't even thought about.

George Washington Carver’s house on a small farm in Diamond Grove, Missouri. The building was later relocated to the Henry Ford Museum in Greenfield Village. (Photo: Chuck Miller, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Of course, Dr. Carver people today think of you and the peanut, that little thing that grows under ground—a ground nut they call it in Africa. What inspired you to do so much with the peanut?

WILLIAMS: Well, let me tell you a little bit about the lonely goober as I sometimes call it. After I'd been in the South for a number of years, I noticed that the cotton farmers there were seeing reduced yields. Cotton takes nitrogen from the soil, over time reducing the soil's ability to nourish the plant. So I decided we needed to come up with a way to add more nutrients to the soil. And I knew that legumes peas, beans, pod-bearing plants, I knew that these could do this. So that's how I arrived at the peanut. Then I had an issue in that folks were growing all these peanuts, but they didn't exactly know what to do with them. I mean, you can only eat so many peanuts. And so we started producing bulletins, and in those bulletins, I would have recipes for my peanut punch. My mock chicken made out of peanut. I would even have a sort of coffee made out of peanuts. You know, we used other real coffee beans with it. But the peanuts just helped it go further.

CURWOOD: What's your favorite peanut recipe Dr. Carver?

WILLIAMS: I'm particular to just a very fine roasted peanut. It's nice, you can have them in your pockets and when you go out on walks, you can take them with you. And you get lots of great nutrition from them. You may know that when I testified before the US House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee, I spoke of my love of the peanut and the sweet potato, and talked about how from those two, you could get most of the nutrition a person needs. And so I like to say that I used the peanut to help deal with poor nutrition, to help deal with poverty, because then the folks could save money if they had things that they could eat themselves that they'd grown, and then also prejudice, because much of my work with the peanut helped bring people together. And I'm really proud of that.

CURWOOD: So talk to me how you dealt with the racial turmoil that was taking hold within your society there in Alabama.

WILLIAMS: The interesting thing about race in the south is that the races have lived together there for a long time, and they really know each other. I found that when you can sit down person to person, you can see that what some people might describe as differences are not really differences at all. And I think my work with the peanut and at the Tuskegee Institute helped show many other farmers that. Because many of the the white farmers, they were able to benefit from what we were doing. They saw through our work, through our industry, that we were just as creative, just as smart, just as hard working as they were. And when we were able to help improve their lives, they thought maybe we were looking at these folks wrong. Maybe we were understanding their capabilities wrong their humanity wrong. When I left Iowa in 1896 some folks were surprised by my decision to move south. But when I was a little boy, a wise woman who took me in called Aunt Mariah Watkins, she told me something along the lines of "lift as you climb". And that was something I never forgot: "lift as you climb". And she told me any book learning that I might get that I should make it a point to share with our people.

A glass of homemade peanut punch, a George Washington Carver sanctioned peanut delicacy. (Photo: Bedinek, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

[RADIO STATIC]

CURWOOD: Dr. Carver, are you still there?

WILLIAMS: Yes, sir. I'm here. Yes, sir. I'm here.

CURWOOD: A little interference here. But talk to me about today. What kind of agricultural future do you envision for our country? You know, what have we been able to achieve since then?

WILLIAMS: I always believe that if we took care of the land, the land would take care of us. And we just need to make sure and ask ourselves, is that what we're doing? Are we respecting the bounty that the land gives us? And so I think those are the questions that I would pose to anyone interested in agriculture today. One of the issues that I first saw when I got to the south, was how horrible, how invidious the system of sharecropping was, because there were all of these barriers put up to people being as good of stewards of the land as they could have been. And I encouraged the farmers there, you know, to plant personal gardens to, in addition to just crops that they might eat or sell, because I thought this was good for the land and it was good for them as individuals. And so with the sharecropping system, the folks who I was most dealing with in Alabama, they were not being respected. And so I think we need to make sure we consider that today the same way we needed to consider it back then.

#OTD in 1942, Dr. George Washington Carver visited Henry Ford to help the automaker develop plastic & rubber substitutes using plants. Ford had a long-standing belief that biofuel & other alternative methods to produce materials were the wave of the future. #ThisDayInAutoHeritage pic.twitter.com/QkplvFiD4t

— MotorCities (@MotorCities) July 19, 2021

CURWOOD: Now, some folks argue that we need another green revolution to be able to feed the growing population, but others say the issue is not so much food production as food distribution and food waste. Talk to me a bit about your concern for food production in today's modern age.

WILLIAMS: I have always believed that we could produce enough to feed us all, if we were smart about what we did and how we did it. And I think today, there's something called the local foods movement. We didn't call it that when I was first working, we were just calling it, producing near you, selling it near you. And we encouraged people to grow things that they needed and that they could use. And some of the distribution problems that we see today, I think might be solved if we look to the lessons from back then in terms of encouraging folks to grow what they can, to be creative in what they grew and how they grew it. And then also in finding ways to share and to make substitutes for things. I think those are just some of the issues that could be addressed.

CURWOOD: Of course, your name George Washington Carver is so important, but what other names or historical figures you think we should be paying attention to?

WILLIAMS: Well let me just say that I have been privileged to interact with and know many brilliant, wonderful people. Beginning In 1896, when Booker T. Washington asked me to come teach at his Tuskegee Institute. A brilliant man, he wrote a number of autobiographies, I would encourage folks to begin with Up From Slavery. That one was really insightful. I also had the privilege of knowing Dr. W. E. B. DuBois. Now, some folks, you know, are aware, that Dr. DuBois and Booker T. Washington had some differences of opinion, but several people forget that at one point, they were on quite friendly terms. And in fact, Dr. Dubois even taught for a summer at the Tuskegee Institute. I had the privilege of knowing the great poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. He came to Tuskegee on a number of occasions, and he even wrote a wonderful poem for the dedication of Dorothy Hall, a building that many years later I would come to live in. I also got to know the great opera singer Roland Hayes, Mary McLeod Bethune, a wonderful educator from Florida. If you don't know the story about how she started that school, by making money washing clothes, it's a wonderful story to learn about. You may have heard of the Kellogg brothers, W. K. and J. H. Kellogg, and I corresponded with both of them for a number of years. I had the privilege of knowing Mr. Henry Ford. He created the Ford Motor Company. And he visited me on a number of occasions in Tuskegee, as you may, you may or may not know this, he built a school near his home in Georgia for colored children and named it after me. And I was really honored that he would do so. I visited him in Dearborn, Michigan. We met, I believe it was 1936 or so at a chemurgy conference. And it's the development of industrial uses for farm byproducts. I think they might call it biotechnology today. And and I think when you study some of these folks, you will see that there were many things that he was wrong about. I think that's the interesting thing that when we look at folks from the past, the folks from the day, that there are lessons that we can learn from them, even recognizing that they're not perfect.

In addition to being an actor and playwright, Williams is also the assistant attorney general of the Iowa Department of Justice. (Photo: Courtesy of Paxton Williams)

[RADIO STATIC]

CURWOOD: Dr. Carver, are you still there?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, I'm here. I'm here.

CURWOOD: So what about yourself? What mistakes did you make?

WILLIAMS: You know, I would say that there were times when I probably could have been more forceful in standing up for the rights of all people, but especially my people. Folks wrote about that at times about me. They said that I was not as vocal as I could have been, I didn't use my voice. I do understand the critique. I do understand what they wanted. Because you know, as you know, I knew a number of wonderful people, people who could make real change and who could do things and there were probably times when I probably could have said more to them about society and about life in general.

[MUSIC: Caratini Jazz Ensemble, “West End Blues” on Darling Nellie Gray (Variations sur la musique de Louis Armstrong), Label Bleu]

WILLIAMS: I do believe I'll have to be leaving shortly. And I wanted to thank you for taking the time to visit with me.

CURWOOD: Well, I appreciate you taking the time to come from the past to the present to visit with us. Thank you so much.

WILLIAMS: Thank you, thank you.

CURWOOD: George Washington Carver was channeled by actor and playwright Paxton Williams. He wrote and frequently performs a one-man play in which he portrays George Washington Carver.

Related links:

- Paxton Williams' Profile

- Biography about George Washington Carver

- George Washington Carver’s peanut bulletins

[MUSIC: Caratini Jazz Ensemble, “West End Blues” on Darling Nellie Gray (Variations sur la musique de Louis Armstrong), Label Bleu]

DOERING: PFAS chemicals are linked to reduced fertility, metabolic disorders, and cancers. And researchers recently found concentrations of the forever chemicals are especially high in freshwater fish, including varieties eaten by people.

ANDREWS: We actually made a comparison showing that consuming a single fish serving, and these are freshwater wild caught or locally caught fish, would be equivalent to drinking over a month of contaminated drinking water.

DOERING: We’ll have some tips for how to eat fish safely, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Caratini Jazz Ensemble, “West End Blues” on Darling Nellie Gray (Variations sur la musique de Louis Armstrong), Label Bleu]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Fern Al-ling, Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Jusneel Mahal, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth