November 4, 2022

Air Date: November 4, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

New President to Protect Amazon

View the page for this story

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, known as Lula, is headed back to another term in the Brazilian Presidency. In sharp contrast to defeated incumbent Jair Bolsonaro, Lula has pledged to protect the Brazilian Amazon and indigenous communities from illegal mining, agriculture and land grabbing. Karla Mendes, and contributing editor to Mongabay joined Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss. (09:05)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

On this week's trip beyond the headlines, Environmental Health News weekend editor Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb examine the $1 billion now available to help low income school districts purchase electric buses. Then, the two discuss a silver lining from Vladimir Putin's invasion of Ukraine: the prediction of a faster transition to global clean energy. Finally, Peter and Bobby take a look through the history books at the life and death of a chemist who invented two tiny compounds with huge consequences. (04:50)

Toxic Air in Utero

View the page for this story

Before they’ve even taken their first breath, many if not most babies are exposed to air pollution that passes from their mother’s blood stream through the placenta. And an October 2022 study out of Europe found that the more air pollution a pregnant person is exposed to, the more black carbon particles from burning fossil fuels are found in the lungs, brain, and liver of the fetus. For more, Host Bobby Bascomb spoke with pediatrician Aaron Bernstein, the Interim Director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health (11:53)

The Ancient Call of the Sandhill Crane

/ Jennifer JunghansView the page for this story

Each fall, sandhill cranes return to winter refuges in the southern U.S. and Mexico. Writer Jennifer Junghans reflects on what their ancient calls evoke in her when they return to her city of Sacramento, California each year. (04:35)

An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us

View the page for this story

Every animal species experiences the world in a way that is totally unique to them. Mantis shrimp, for example, have many more photoreceptors than humans and can filter polarized light, and star-nosed moles can smell under water. At a recent Living on Earth Book Club event, author Ed Yong joined Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood to share the fascinating sensory abilities he learned about in researching his new book, “An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us”. (15:53)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

221104 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Aaron Bernstein, Karla Mendes, Ed Yong

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Jennifer Junghans

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

With Brazil’s new pro-environment president international funding for protecting the Amazon will likely start up again.

MENDES: One of the key issues that we've been facing during these years are lack of funding to bolster projects for communities in the Amazon because of course these communities live there, they protect the forest. So having this money back to this fund is really, really great news.

BASCOMB: Also, researchers find air pollution particles in the organs of unborn babies.

BERNSTEIN: We already had studies showing that breathing air pollution was bad for pregnancies but people really want to know exactly how this works and what this study shows is that the air pollution that’s outside gets inside the mother and crosses the placenta and gets into the baby.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

New President to Protect Amazon

Brazil’s 2022 Presidential winner Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva (left) campaigned in Porto Alegre with his wife Janja Lula da Silva (right) and Vice President-elect Geraldo Alckim (middle). (Photo: Thayse Ribeiro, Flickr, Mídia NINJA, CC BY NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Brazil has elected a new president. Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, commonly known as Lula, won a tight run-off election against right wing incumbent Jair Bolsonaro. Lula’s new government is expected to have a profoundly different approach towards indigenous rights and protecting the Brazilian Amazon. This is Lula’s third term as president, he served from 2003 to 2010 and in that time enacted policies that resulted in an 80 percent drop in deforestation rates in the Amazon. In his acceptance speech Lula says he is once again going to prove that it’s possible to generate wealth without destroying the environment.

[LUIZ INACIO LULA DA SILVA SPEAKING IN PORTUGUESE]

BASCOMB: Jair Bolsonaro, in contrast, slashed budgets for environmental agencies and encouraged miners and agriculturalists to illegally push into the Amazon, which led to a roughly 70 percent increase in deforestation over his four years in office. And Mr. Bolsonaro gutted FUNAI, that’s the government agency that oversees Indigenous affairs. It helps tribal peoples protect their land from invaders and officially recognize, or demarcate, indigenous territory. For more I’m joined now by Karla Mendes, an environmental journalist and contributing editor to Mongabay. Karla, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MENDES: Hey Bobby, thank you so much for the opportunity to be here again.

BASCOMB: So Karla, what changes are you expecting with the new president?

MENDES: Now, as Lula won the election, we are hopeful that all this will be reversed. Because FUNAI, for example, this change was through a decree. So Lula has the power to revoke it. So it can be an immediate change. At the same time, Lula promised to give FUNAI to be led by an indigenous person, which is really important because the actual head of FUNAI is aligned with Bolsonaro's anti-indigenous measures. So and at the same time, Lula also promised to create a ministry of Indigenous, an Indigenous Ministry. So this will also be key to try to reverse all the losses of rights and threats and violence that they've been suffering due to all this economic interest that have been authorized by the president over their lands.

Indigenous activists Célia Xakriabá (left) and Sônia Guajajara (right) were elected as federal deputies. They are part of the Bancada do Cocar (Feathered Headdress Caucus) that aims to halt the escalating anti-Indigenous and anti-environmental agenda in legislative power since President Jair Bolsonaro took office in January 2019. (Photo: Courtesy of Célia Xakriabá and Sônia Guajajara.)

BASCOMB: Now understand that five indigenous candidates were elected to Brazil's national congress. That's the highest number in the country's history. But the Congress is still solidly conservative and aligned with President Bolsonaro's policies. What does this mean for Brazilian politics going forward?

MENDES: Yeah, thanks for the question, that's an interesting point for us to explore. Because the National Congress may be the toughest battle. We saw in this election, Bolsonaro's allies being reelected, like almost 60% of them reelected. Right wing candidates control more than a third of the lower house of the Congress. And in the Senate, the situation is even worse, because the Senate so far was where they blocked the worst attacks against the environment. And now Bolsonaro's supporters control like half of the Senate. But at the same time, we had this historical election of Indigenous people and beyond the Indigenous people, there are the left wing linkage to the Quilombola movement which are the descendants of Afro Brazilian slaves, runaway slaves, LGBT. So all of them, this alliance between them, it's really important. So having all this people and women, so great to see women, more women in the Congress, I think we can be positive.

Heavy equipment found at an illegal mining site in the Amazon during Operation Green Brazil, a 2019 government-led initiative to combat fires and environmental crimes. Environmental and Indigenous organizations fear illegal mining will increase if a slate of proposed bills is passed. (Photo: Courtesy of Agência Brasil)

BASCOMB: You know, the reason that we're talking so much about Indigenous people here in Brazil is that, you know, enabling Indigenous people to stay on their land is one of the best ways to protect that land. I've seen maps where you can overlay Indigenous territory with intact Forest, and it's a precise match. I mean, where you have intact people, you have intact forest, it's really just that cut and dry.

MENDES: Yeah, now that's true. That's true. There are several scientific studies proven this. And I can tell from my experience going on the ground, we can see how the area preserved and the temperature is different with the trees and all that around. The vast majority of the indigenous people, they really fight for the environment, they fight for the world, for the planet. And they need to be there. They just, they think about not just about them, they're thinking about the planet and the world because the Amazon is here in Brazil and in other countries, but it has an effect in the entire world. So that's why it's so important to demarcate the land.

BASCOMB: Another threat in the Amazon is some of the chemicals that can be used in agriculture there. You've written about an agrochemical bill that's been dubbed the agenda of death, that would allow agricultural chemicals in the Amazon that had previously been illegal. Now, that's still working through Congress, as I understand it, but it has quite a lot of support there. Can you tell us more about those chemicals in question and what's likely to happen with this change of government?

Deforestation in Brazil's Amazon rainforest hit a 15-year high in 2021 as Bolsonaro's administration continued to weaken government bodies responsible for monitoring the environment and enforcing laws to protect the forest. https://t.co/QfoUeYm0Qs

— Greenpeace (@Greenpeace) February 2, 2022

MENDES: Yeah, agrochemicals and pesticides are also a really huge problem for the Amazon and for the Brazilian biomes. And we had this, we call this death package that includes a bill that losing regulation for the use of agrochemicals for agriculture. Because now they have to be approved under the Ministry of Agriculture and also through the Ministry of Health. And what they want is to remove the Ministry of Health and just give all the power to the Ministry of Agriculture, so it's not good at all. During Bolsonaro government, we saw a huge increase of pesticides to be authorized to be used in agriculture. And the pesticides, the effect of the pesticides on the traditional community for people who live in the areas where it's being produced, the effects are really, really terrible. Last year, I published a story about the water contamination by pesticides using palm oil crops, and we saw studies showing that the rivers inside Indigenous territories and also the even the water wells they were using, had traces of pesticides.

BASCOMB: So if this death agenda, as it's been called, does pass through Congress. Does the President have the right to veto it as we do here in the United States?

MENDES: Yes. There’s alternative and to be vetoed by the President. And there is also the option of challenging that law before courts.

BASCOMB: Well, there's also talk of reinstating the Amazon Fund. Now that's a pot of money donated mostly by Norway and Germany to protect the Amazon. The fund was halted under Mr. Bolsonaro as deforestation increased, but now the Lula administration has the opportunity to revive the fund. Where does he stand on that?

Indigenous leaders Agnaldo Franciso, left, of the Pataxó Hãhãhãe people, and Cleonice Pankararu, right, of the Pankararu/Pataxó. They told reporters about the persecution they faced under the Bolsonaro administration and how they will continue to fight against proposed legislation that threatens their lands and communities. (Photo: Courtesy of the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI))

MENDES: This is really, really great news. And I think that's the first real impact of Lula's election, because there was a lot of discussions, a lot of promise, but what can really be made. And here was an example that because it happened during the first years of Bolsonaro government, there were fires, and he denying the data and deforestation and all this so what other countries that help and send money to Brazil to help protect in the Amazon what they did, they blocked the money. And as soon as Lula was elected, there was his announcement. And it's really timely because one of the key issues that we've been facing during these years are budget cuts to environmental agents and also lack of funding to bolster projects for communities in the Amazon, because of course this community live there, they need to survive. But there are several ways to co-live with the forest and I've visited several projects where I see that. They help protect the harvest on the forest, but they protect the forest itself and also against invaders. So having this money back to this fund is really, really great news.

BASCOMB: Karla Mendes is an environmental journalist and contributing editor to Mongabay. Karla, thanks so much for your time again today.

MENDES: Thank you so much for the opportunity to be here again.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “Lula Vowed to Safeguard the Amazon. After Bolsonaro, It Won’t Be Easy”

- Mongabay | “Brazil Agrochemical Bill Nears Passage in Bolsonaro’s ‘Agenda of Death’”

- Mongabay | “Brazil’s Biggest Elected Indigenous Caucus to Face Tough 2023 Congress”

- Mongabay | “Activists Slam Bolsonaro Rule Change Seen as Ending Demarcation of Indigenous Lands”

[MUSIC: Luiz Bonfa, “Malaguena Salerosa” on The Brazilian Scene, The Verve Music Group]

Beyond the Headlines

The Inflation Reduction Act has made $1 billion available to purchase electric school buses for low income school districts throughout the United States. (Photo: Caitlin Looby, UCI Sustainability, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, it's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby, there's a piece of the Biden Inflation Reduction Act. It's about a billion dollars to buy new electric school buses for primarily low-income school districts across the country. And it's a two for one because not only would it be another arrow in the quiver of clean energy and electric buses, electric vehicles, but it would also deal with diesel exhaust from those buses. That is a major impact for asthma in low-income parts of the US.

BASCOMB: Yeah, it seems like a win-win. I mean, think of the health of children who won't be breathing in diesel fumes, and, of course, the, you know, reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. And too, you know, it seems like a no-brainer to me. I mean, buses aren't going far, you know, they don't have to worry about running out of a charge, and you have the infrastructure all in place. It seems like a great idea.

DYKSTRA: Right? It's something that's easily done. A billion dollars doesn't hurt. But the kind of startup money like that, hoping that it's a successful project, is something that can give a goose to purchasing electric school buses everywhere.

BASCOMB: Yeah, exactly. Well, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: A benefit, if anything out of war can be a benefit, from Putin's invasion of Ukraine, is that the International Atomic Energy Agency says that the war is actually going to speed up, not slow down, the development of clean energy across the world.

The International Energy Agency forecasts that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent energy crisis is more likely to speed up the global transition to clean energy, rather than slow it down. Pictured above is Perovo Solar Park in Ukraine. (Photo: Activ Solar, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Wow. Well, I mean, war is awful, of course. But if there is a silver lining, we certainly need to move quickly towards more clean energy. You know, I have to think that that's a consequence that Vladimir Putin probably wasn't expecting when he invaded Ukraine, you know, especially given Russia is so dependent on fossil fuel exports for their economy.

DYKSTRA: It is and Putin had looked toward Russian natural gas, Russian oil, as the means he could dangle in front of the world's economy and energy infrastructure to have us, basically in the thrall of fossil fuels, Russia being a major player, and that's something that may not work quite as well as he suspected it would.

BASCOMB: No. Well, we hope so anyway. Well, what do you see for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: November 2 1944, is the date of the death of a rockstar scientist from the early 20th century. Thomas Midgley invented two things that were viewed as breakthroughs in chemistry in the early half of the century, that we later found out were huge problems instead.

BASCOMB: Hmm. All right. So what did Thomas Midgley invent then?

DYKSTRA: The first thing is he invented the use of tetraethyl lead as a gasoline additive. It helped conquer engine knock, which was a big menace to engines running smoothly in automobiles. And his second thing was he invented chlorofluorocarbons. In their use of coolants, chlorofluorocarbons became a breakthrough, not only in refrigerants, but an air conditioning as well. And as we later found out, chlorofluorocarbons, CFCs, are also a major cause of destruction of the ozone layer.

Thomas Midgley Jr. was an American chemist responsible for developing both tetraethyllead and chlorofluorocarbons. (Photo: Office for Emergency Management, Library of Congress, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Mmhmm. And of course, we know now that leaded gasoline is terrible for air quality, reduced IQ in children that were exposed to it. I guess, file those inventions under "seemed like a good idea at the time", huh?

DYKSTRA: Well, “what could possibly go wrong" file is the other place they belong. And of course, both of these problems were later conquered by the Montreal Protocol, which has cut down drastically on the use of CFCs and by the banning in nearly all nations of the use of lead in vehicle fuels and gasoline.

BASCOMB: All right, well, better late than never, I suppose. Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Grist | “US Unveils $1 Billion Effort to Electrify School Buses”

- The New York Times | “War in Ukraine Likely to Speed, Not Slow, Shift to Clean Energy, I.E.A. Says”

- Read more about Thomas Midgley Jr.

[MUSIC: Luiz Bonfa, “Bye Bye Blues” on The Brazilian Scene, The Verve Music Group]

BASCOMB: Coming up – New research finds air pollution particles in the organs of unborn babies. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Luiz Bonfa, “Bye Bye Blues” on The Brazilian Scene, The Verve Music Group]

Toxic Air in Utero

A 2022 study out of Europe found black carbon particles from pollution in the brains, lungs, and livers of fetuses. (Photo: Michael Kordahi, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Before they’ve even taken their first breath, most babies are exposed to air pollution that passes from their mother’s blood stream through the placenta. And a recent study out of Europe found essentially a smoking gun for that exposure. Researchers in Scotland and Belgium looked at 96 randomly selected non-smoking mothers and their fetuses for the study. They found that the more air pollution a pregnant person is exposed to, the more black carbon particles from burning fossil fuels are found in the lungs, brain, and liver of the fetus. That’s especially dire news for communities of color in the US which are disproportionately exposed to higher levels of pollutants. For more, I’m joined now by pediatrician Aaron Bernstein, the interim director of The Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Bernstein, welcome back to Living on Earth!

BERNSTEIN: Great to be with you, Bobby.

BASCOMB: So first off, please give us the basics of this study. What were the researchers trying to learn here? And how did they go about it?

BERNSTEIN: This is a kind of smoking gun study. Meaning, we already had studies showing that breathing air pollution was bad for pregnancies. That's been clear for a while. But people really want to take it to the mat. They want to know sort of exactly how this works. And, and what this study shows is that the air pollution that's outside gets inside the mother and crosses the placenta and gets into the baby. Prior to this study, we even had research showing that these air particles that they found in the fetus did get to the placenta. But this study not only showed that, they showed that they got into the cord blood and even into the fetal tissues, and perhaps most compellingly showed that the amount that gets into the fetal tissues is proportionate to the amount that the mother is exposed to. So, you know, this is a study that really makes very clear that the amount of air pollution that, you know, people who are pregnant get exposed to, is really going to be proportionate to the amount of air pollution that their fetuses get dosed with.

BASCOMB: And as I understand it, the women that were involved in this study were all non-smokers and living in a community that had relatively good air quality. We're not talking about someplace, you know, really beyond the pale in terms of air quality here.

BERNSTEIN: That's right. Yeah, they did a really nice job of making sure that what they were seeing in this, in the pollution exposures, what was from breathing air pollution, that's not, again, from cigarette smoking. The specific kind of pollution they looked at is this stuff called black carbon. That is a part of what we would call particulate matter. Particulate matter is air pollution that's essentially a particle floating in the air, and it's judged on its size. And black carbon is a fraction of that that actually looks dark. So that's how they see it. They take a piece of filter paper, and they capture the air pollution, they look at it under a microscope, and the part that's dark is called black carbon. And that's the fraction they looked at. But you can rest assured that they're not just being exposed to black carbon, they're being exposed to the full spectrum of particles that would come with that. Now, the next question is, where does this stuff come from? And for most folks, it's from burning stuff. In the United States, black carbon is sourced from burning coal, for sure. Burning diesel fuel is a big source. But you know, other stuff that gets burned can source black carbon as well: fires, forest fires can source black carbon. But you know, for the average person on the average day, their black carbon exposure is probably coming from burning fossil fuels.

Exposure to black carbon particles may lead to neurocognitive disorders later in life. (Photo: Ricky Willis, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: And we know about the health consequences for adults that are exposed to that type of air pollution, you know, lung disease, cardiac disease, even. What do we know about fetuses, babies that are not yet born, that are being exposed to that same air pollution via their mothers?

BERNSTEIN: So it's pretty clear that pregnancies don't come out as well. They end too early, the babies that are born are smaller than they should be. There's some evidence that, you know, this particulate burden that's going into the fetal circulation is actually damaging organs before the kids are even born. And those kids may, in fact, have more problems with neurodevelopment. So they may be at more risk for things like autism, other neuro, what we'd call neurocognitive disorders.

BASCOMB: And it's getting into some very, very important organs. I mean, of course, the developing fetus, everything is important, right, inherently, but we're talking about brains and lungs here. I mean, these are very crucial organs that are being affected.

BERNSTEIN: Yeah, I mean, you know, there's no organ that's spared from particulate pollution. So, some seem to be more sensitive than others. And again, you know, developing tissues and fetuses are developing enormously rapidly, right? I mean, it's just stunning how quickly things are growing and dividing and connecting. And so disruption of that can cause real problems. But you know, to me, Bobby, this whole question around how bad is it, it really needs to be flipped on his head, which is, how much better off are we going to be when we stop dosing people with this pollution? And there's a lot of conversation right now with, for example, the EPA about revising things around what we would call the criteria air pollutants. These are the air pollutants we know are really bad for health. And often when EPA is making rules, they don't include things like the effects on pregnancies or the effects on children, because the research base isn't as big as it is for older people. And so I think this piece of research in particular can be very helpful when EPA is looking to improve air quality for everybody, because it connects the dots for them. It actually shows pretty clearly that that pollution is getting into the mother, into the placenta, past the placenta, into the fetus. It's going to help us protect women who are pregnant and children better. It gives us some real scientific "oomph" to take a step forward and include those values of reducing pollution into the rules we have on the books.

Communities of color in the United States are disproportionately exposed to black carbon sources like particulates from burning diesel fuel. (Photo: Bob Adams, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, what can, let's say, a pregnant woman do, who's maybe listening to us right now. I mean, it's very difficult to just pick up and move, you know, you can't leave your home, your job and everything. What kind of measures can people take to limit their exposure now that we know how serious it is?

BERNSTEIN: I'm really glad you asked that, Bobby. So there's actually many things. The first is to recognize that even though a lot of this pollution is coming from outside, some of it can come from inside. And sometimes we may not be aware that we're creating air pollution in our homes. So common sources of indoor air pollution are gas cooktops. A lot of folks have gas cooktops that are not well ventilated. Ideally, if you are burning gas in your house, you have a vent that sucks the, you know, combustion products of that gas out. Obviously, here in New England in the winter, you're not going to open your door or window necessarily, but certainly when the weather's better, I would strongly encourage people to do that if they don't have a vent. We burn wood. So fireplaces, wood burning stoves. In the ideal world, wood burning stoves are well ventilated, they're sealed, and none of that gets into a house. But I can tell you, that is rarely the case. And then there's other sources of pollution that might not be particulate pollution, but is also very damaging to, for example, lungs. You know, air fresheners, incense. These things can often release chemicals into the air that are very, in fact, irritating to our lungs, and certainly the respiratory tract. I should also mention, I've been in several situations where some families didn't know that idling vehicles created exhaust that was bad for people's health. And so if you have an attached garage in the winter, you know, I think it's important to remember that you know, you idle the car to warm up in the garage, that pollution is probably going into your house. But then there's even stuff, even if you know you're not creating any source of pollution indoors, there are things you can do to help deal with air pollution that may be coming in from outside. That has to do with making sure that the air filter on your furnace, to the extent you can deal with that, is changed regularly. You go to any hardware store these days, and they can give you a new one. You know, a lot of people got air filters during the pandemic for COVID transmission. But if you don't have one of those, and you don't want to spend a lot of money, you can go online now and see, you know, a schematic for creating a pretty macgyvered air filter in your house with just a box fan and some of those filters you might put in the furnace. For like 20 or 30 bucks, you can actually make an indoor air purifier that's reasonably good. I would suggest that if you're going to do that, put it probably in a bedroom, because you spend a lot of time in your bedroom at night. And that is a relatively effective way as a low-cost option to get some of these particles.

Indoor air pollution sources can include gas stoves, woodburning stoves, air fresheners, and incense. (Photo: Quasamime, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, these are all great suggestions. But the pollution problem is so much bigger than any one person can possibly address. It seems like more of a societal issue. What do you think should be done on a grander scale to really tackle this problem?

BERNSTEIN: Vote is a good one. Our air quality as a society is determined by our elected officials and, in the case of the presidency, the agencies that are tasked with dealing with these things. So that's a big one, given we're headed into election season here. And I think beyond that, you know, you look at the reality of air quality United States. It's very clear that we've done a pretty good job here. The Clean Air Act, decades in the making now, has really reduced many of the bad air pollutants massively and saved so many lives and so many dollars. The estimate is that it's returned about 30 to one. So every dollar we spent to reduce air pollution, we've benefited 30 fold. So I think we can continue to build on those things. I think one of the challenges that we need to address, the Clean Air Act was based upon dealing mostly with power plants and things that didn't move. And now a lot of the air pollution is coming from things that do move. And so when we think about fuel efficiency requirements and cars, the transition to EVs, these are our next great opportunity to really improve air quality, particularly in urban areas, where a lot of the pollution can come from cars. And I think for you know, in terms of getting more local control, when you're dealing in your town or city with issues around transportation. Most people in United States if they're breathing the kind of pollution that was in the study we were talking about, it's from burning, you know, liquid fuels like diesel. And cities and local jurisdictions have a real say about how those things may work in their communities. And for that matter how people may be able to access public transportation, getting people out of vehicles and onto bicycles and walking and so forth. So I think even at the local level, there are important decisions about how transportation systems work that affect people's exposures.

Installing an air filter in your home is one way to mitigate indoor air pollution. (Photo: Jonathan Lidbeck, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, this study that we're talking about was conducted in Scotland and Belgium, but here in the US, we know that communities of color are disproportionately affected by pollution, largely because of historically racist practices like redlining. How can we better respond to this research with an environmental justice lens?

BERNSTEIN: Well, I think the good news here is that because of this racist history, when we take steps to move away from fossil fuels, we have the chance to promote justice. To my point earlier about how so much pollution is happening from transportation within cities, if you look across the United States, the estimates are about one in five children develop asthma because they're breathing tailpipe exhaust. And when they looked at this, in, I think, in a really superbly done study in Oakland, where they were able to match block by block air pollution exposures through driving in a car that had an air pollution monitor in it with health records of people living block by block. They showed that in areas that were richer, the pollution sourced asthma burden was about the national average about one in five, but in lower wealth communities of color it was about three in five. And that's, Bobby, to the injustice you described, which is those communities are where the big freeways are, it's where the diesel trucks are. So what does that mean? That means that if we actually address these mobile pollution sources, particularly the diesel trucks, that the communities that have been burdened heaviest are going to benefit the most.

BASCOMB: Aaron Bernstein is the interim director of the Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Bernstein, thank you so much for your time today.

BERNSTEIN: Great to be with you, Bobby.

Related links:

- Read the study on maternal exposure to black carbon particles in The Lancet: Planetary Health

- Read more on air pollution

- KHN.org | “Tracking Air Quality Block by Block”

- Environmental Defense Fund | “How Pollution Impacts Health in West Oakland”

[MUSIC: The North Sea Trio, “On A Clear Day” Single, The North Shore Trio]

The Ancient Call of the Sandhill Crane

Sandhill cranes come in for a landing at sunset (Photo: Georgia Richards, used with permission)

BASCOMB: Sandhill cranes have one of the longest fossil histories of any living bird species, going back at least two and a half million years. Today, some overwinter in refuges near cities like Sacramento, where writer Jennifer Junghans lives.

JUNGHANS: Each fall I wait with anticipation for their arrival. The unmistakable call of Sandhill Cranes overhead, reaching the end of their fall migration from their breeding grounds to overwinter in warmer destinations.

[SANDHILL CRANES CALLING, MACAULAY LIBRARY AT THE CORNELL LAB OF ORNITHOLOGY, CONTRIBUTOR: DENNIS LEONARD]

JUNGHANS: It’s a sacred call to me — an auditory equinox twice a year marking the turn of the seasons. So enchanting I’m inclined to trumpet a call of my own, announcing the magnificence of the moment to all who will listen. Marveling at the wonder that we have chosen the same geography to call home for the next six months.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Thread Indigo,” Textiles, Blue Dot Sessions 2020]

JUNGHANS: While the numbers of these ancient birds have been reduced to a fraction of what they used to be, we haven’t yet upset the rhythm of their migratory patterns. An unspoiled grain of wildness I feed upon, to satisfy my hunger for joy, solace, strength and comfort. The same way I feed on the warmth of the sun beneath my skin.

Sandhill cranes rely on open meadow and wetland habitats (Photo: Jennifer Junghans, used with permission)

[CARDINAL SONG, GENGHIS ATTENBOROUGH VIA FREESOUND.ORG, CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY-NC 3.0]

[WOODLAND BIRDSONG, JUSKIDDINK VIA FREESOUND.ORG, CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 4.0]

JUNGHANS: The musical notes of birds.

[WOOD THRUSH SONG, PEACEMEDITATION VIA FREESOUND.ORG, CREATIVE COMMONS 1.0]

JUNGHANS: The shade of trees. Wild places to wander that are alive with creatures.

[RUSHING RIVER SOUND, CASTLEOFSAMPLES VIA FREESOUND.ORG, CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 3.0]

JUNGHANS: Rushing rivers. Symphonies of croaking frogs at dusk.

[FROGS CROAKING, DANJOCROSS VIA FREESOUND.ORG, CREATIVE COMMONS 1.0]

JUNGHANS: A ripe fig begging to be plucked. Earth beneath my bare feet.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Thread Indigo,” Textiles, Blue Dot Sessions 2020]

JUNGHANS: I think my whole life has been about getting back to nature, an idea that’s weaving its way back into our global consciousness with forest bathing and a focus on reviving outdoor play among children. A reckoning that we have lost something we instinctively need. I think about that a lot in the context of our expanding footprint and advancing technology. Our communication with others reshaped into the form of a tweet, a text, a ding or a like. Concrete jungles sprawling over wild land to house us in mega homes we’ll work the rest of our lives to pay for. A continuum that shuttles us further away from nature, from the way things used to be.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Thread Indigo,” Textiles, Blue Dot Sessions 2020]

JUNGHANS: But come fall, when the Sandhill Cranes trumpet their arrival home, the distance between me and the natural world compresses. Seated at dusk at the edge of the marsh where wild things live, I watch the silhouettes of these grand birds parachute against a blazing orange and pink sky.

Sandhill cranes have long tracheas (windpipes) that allow them to produce their unique trumpeting call. (Photo: Georgia Richards, used with permission)

[SANDHILL CRANES CALLING, MACAULAY LIBRARY AT THE CORNELL LAB OF ORNITHOLOGY, CONTRIBUTOR: PAUL MARVIN]

JUNGHANS: They break the still of the water, and gather and murmur in legions to rest in the shallows. It’s magical to witness. And it summons the ancient memories buried somewhere in my being of the wildness from where we came. The same wildness that’s the missing link between our past and our future. And what we do with it will govern how well we fare as individuals and a species.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Thread Indigo,” Textiles, Blue Dot Sessions 2020]

JUNGHANS: I wonder. What are we willing to do with our blip of time on this planet, to ensure that our descendants so distant they will have forgotten us, can still measure the seasons by the ancient call of the Sandhill Crane?

[SANDHILL CRANES CALLING, MACAULAY LIBRARY AT THE CORNELL LAB OF ORNITHOLOGY, CONTRIBUTOR: PAUL MARVIN]

BASCOMB: That’s writer Jennifer Junghans with her essay, “The Ancient Call of the Sandhill Crane.”

Related links:

- Learn more about Sandhill Cranes

- Writer Jennifer Junghans’ website

[MUSIC: Frans Bak, Jan Rordam “Break of Day” Single, Dharma Records Ltd]

BASCOMB: Coming up – From bees that see in ultraviolet to a dog’s extraordinary sense of smell, we’ll explore the many ways animals experience the world just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Frans Bak, Jan Rordam “Break of Day” Single, Dharma Records Ltd]

An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us

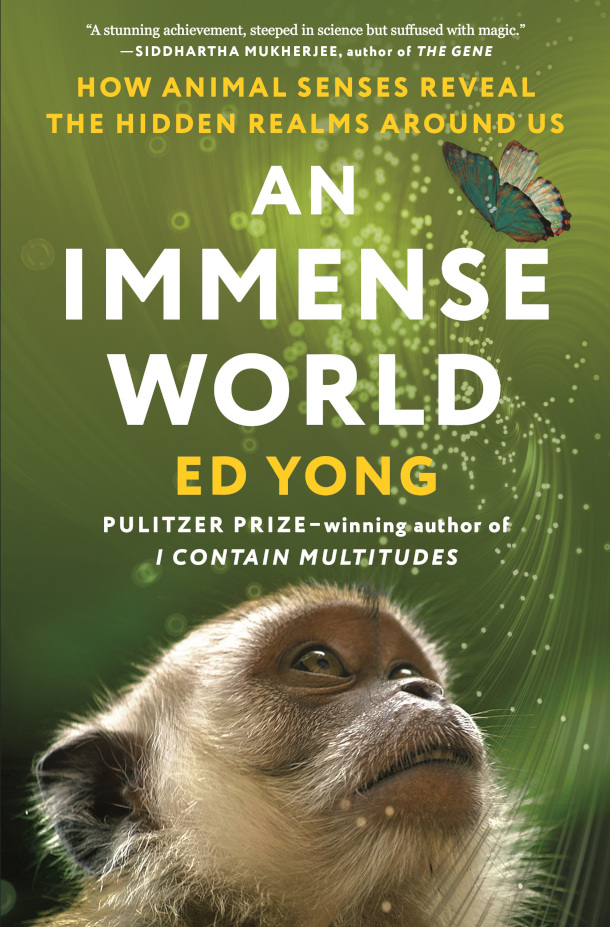

Ed Yong’s 2022 book An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us (Photo: Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Every animal species experiences the world in a way that is totally unique to them. Mantis shrimp, for example, have many more photoreceptors than humans and can filter polarized light, and the star-nosed mole can smell under water. Since we have none of these abilities, it can be hard to relate to other species. But shifting our understanding can help us respect our fellow creatures and make better decisions when it comes to the world we share. Pulitzer Prize winning author Ed Yong set out to explore world the way animals do in his new book “An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us”. Ed joined Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood for a recent LOE book club event.

CURWOOD: Now you've been writing about sensory biology for a decade or more, but think it was 2018 that you decided to do this compendium of what you call 'umwelten', that's a German word. So explain for us, by the way, what's an 'umwelt'?

Ed Yong is the author of An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us (Photo: Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

YONG: So the word 'umwelt' is German for 'environment', but in this context, we're not talking about the physical environment. It is the sensory environment. It is specifically the sights and sounds and textures and smells that exist in the world that I can perceive and that might well be unique to me as an individual or certainly as a species. The core thesis of this book is that every creature has its own particular set of sensory information that it can pick up, it is only perceiving a thin sliver of the fullness of reality. And that, I think, is a wonderfully humbling and expansive idea. It is humbling because I feel sitting here right now that my perception of the world is complete. I'm certainly not, you know, grasping for things that I feel like I'm missing. And yet I'm missing so much. I am not perceiving the ultraviolet colors that a bee or a bird might be able to see, I can't feel the magnetic field of the Earth in the way a sea turtle can. I can't hear ultrasonic frequencies that mice or bats can hear. There is much around me that I am completely oblivious to, even if it doesn't feel that way. But that is also, I think, a beautifully expansive idea. It means that even in the most familiar of settings, there is wonder and magic to be found. By thinking about how my dog sniffs his way around the neighborhoods that I walk down thousands of times every year, I see those environments in new ways. By thinking about, you know, what a seabird like an albatross perceives as it flies over a featureless ocean, the ocean doesn't become so featureless anymore. That's why the book is subtitled in the way it is. It's not just about thinking about animals in a new light. It's about what animals can teach us about thinking about our world in a new and more profound way.

CURWOOD: You also give us a taste of how it matters to them, the whole notion of consciousness for these creatures. I don't want to anthropomorphize this, but I have to wonder, am I torturing my dog when I don't let her stop and sniff when I go walking at my local dog-friendly forest?

Smell is a primary sense for dogs, and they only have two color receptors in their eyes compared to three in humans (Photo: Petr Kratochvil, public domain pictures)

YONG: Yeah, I mean, so I write in that chapter that smell is a primary sense for dogs. It is their main gateway to the world around them, and I think humans forget this sometimes, and, as you say, like a lot of dog owners will yank their dogs along on a walk on the assumption that the point of the walk is exercise. And that is certainly one of the points, but I think it's also really important to let dogs be dogs. I had the good fortune of writing that segment of the book before I got my pandemic puppy. So he's a corgi, he's two years old, his name is Typo, good writer name, and when he sniffs a patch of sidewalk that another dog has peed upon, that is very similar to me checking my Instagram or my Twitter feed, you know, it is a social activity, it tells him about what other dogs that he knows about in the neighborhood have been up to, possibly their health, what they've eaten recently. And if I was to deprive him of that, I think I would be severing him from a really important part of his doghood. You know, it would be like if I went on a hike with a friend and every time I tried to look at a beautiful vista or sunset, my friend covered my eyes and pulled me along. So this is, I think, one of the themes of the book like by not thinking about the umwelten of other animals, we can do them harm, like we can misinterpret their needs, their behaviors, their actions, sometimes in detrimental ways. And conversely, by thinking about their senses, you know, we can afford to them a better quality of life, more respect, and, you know, we can feel a more profound connection to them.

CURWOOD: Indeed, so thank you for that. And there's another jewel of understanding in your book which is around the perception of ultraviolet light. Just explain how this perception of UV works and why there's a difference.

Birds have four color receptors in their eyes, giving them the ability to see ultraviolet hues common on flowers and other birds, but invisible to humans. (Photo: Becky Matsubara, National Science Foundation, CC BY 2.0)

YONG: So color vision works very differently in other species. So humans have trichromatic vision. That means we have three kinds of color-sensing cells in our eyes that combine to create the million or so colors that we can see. A dog has just two, rather than three, and so their color vision is more limited. Now there is this common myth that dogs can't see color at all that is wrong. But their rainbow is really limited to blues and yellows, they don't get the reds, they don't get the violets, they don't really get the greens in the middle. However, a lot of animals including most birds, many insects, some fish, are tetrachromatic, they have four kinds of color-sensing cells, which means that they have access to an entire dimension of colors that we can't see. That might include ultraviolet, a color at the far end of the rainbow, literally beyond violet, that's what 'ultraviolet' means, but it also includes ultraviolet in combination with the other colors that we do see, creating this huge cocktail of hues that we are completely oblivious to. And if you have this kind of vision, then a lot of the world looks very different. So a lot of birds where males and females look identical to our eyes, the sexes actually look very different to the birds themselves, because they have the ability to see all of these extra colors than we can't. Flowers can look very different. A lot of flowers have vivid ultraviolet markings on them that guide insects to sources of nectar. So, a sunflower, if I asked you what color a sunflower is, you'd probably say yellow, but to a bee, a sunflower has a vivid ultraviolet bullseye at its center. There are many, many examples of this and I think it tells us that in much of the world, actually, we are getting a very, very specific view of even things that we consider to be brightly and vividly colored, and that is not what other animals might see

CURWOOD: Yeah, our construct. And hey, somebody that you met while researching this book and who was featured in the same chapter as you have on dolphins and bats is Daniel Kish. Please take a moment to tell us his story and why it's important that more people should hear this story.

It has been known for decades that some humans can echolocate like bats can. The Spotted Bat has the largest ears of any of the 47 bat species in the US, which it uses to hunt moths at night. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

YONG: So Daniel is blind and has been blind from close to birth. And he gets around using a long cane, as many blind people do. But he also echolocates, so he does the thing that bats and dolphins do, he makes loud sharp noises, in Daniel's case with his tongue, he makes these incredibly loud, precise clicks with his tongue, and he perceives the world in the rebounding echoes. And his skill at doing this is really extraordinary, you know, I've gone for walks with Daniel in his neighborhood. And sure he's using the cane and that helps him a lot. But he also has just a very deep awareness of his surroundings, like he'll be able to duck a tree branch lying across his path, he'll be able to tell me, as we're walking along the street, where cars are, where houses are, where lawn converts to gravel converts to concrete, back to lawn. He has this incredible awareness of his surroundings because of echoes. And he's not as skilled as a bat, he likes to point out that they've had millions of years of headstart on him, but he's very good at this. He developed this ability on his own and is now teaching other people to do it. And I think that has a couple of lessons for us. Firstly, the scientific paper in 1944 that first coined the word 'echolocation' used it in the context of bats and people. So it's been well known for a long time that a lot of blind people can do this. And yet, even today, a lot of researchers who study echolocation aren't aware that human echolocation is a thing. And I think that's, in part, because of ableism, because we underestimate the abilities of people who don't have a typical sensorium. And I think it also shows that even within a species, in this case humans, the umwelt can be very, very different. You know, it's often said, when writing about the senses, that humans are a visual species, and it seems to, you know, disregard the millions of people who get by very well without any sight at all. And the other thing that I think that Daniel's story really tells us that's very important is that when thinking about the senses of another animal or another individual, there's always going to be a gap that we cannot cross, I can tell you about what scientific research says about their experience of the world, but I can't really tell you what it's like to be a dog or be a whale. Now, you might think that in the case of Daniel, it would be easy because he's another person we speak the same language he has words with which to describe his experience which an elephant or a dog does not have. And yet, I still don't really know what it's like to experience the world in the way that Daniel does. And I think it's important to recognize that this is a task that we'll never really be able to accomplish. The glory is in the attempt to do so, the effortful work of trying to extend our curiosity and our empathy into the lives of other people and other creatures. And I think that's one of the things I really hope to instill in readers of this book that rather than walk past an animal, you know, rather than trying to shoo it away from our homes, or, or any of those kinds of reactions, I would hope that it makes people stop and watch and think about the other creatures that we share this planet with.

Sea turtles can sense the magnetic field of the Earth, allowing them to migrate great distances and find their way back to exactly the same beach they hatched on (Photo: Wexor Tmg, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: You know, I did find it interesting that some of the pictures that you have in your book, great color photos, there must be, what, 50 or something? One of them included the face of a rattlesnake. You know, and for the first time, I saw this really artfully done photograph of a rattlesnake's face, not about to strike, not with the mouth open, which is, sort of, typically what you might see, but just head on and it made me think, so I think you've accomplished something there. Now, humans, us folk, we are really disrupting this planet and the creatures living on it in so many ways. I mean, how our human activities are having such negative impacts on wildlife, you know, despite our supposedly superior sight, I'm thinking of both noise and light, for example.

Rattlesnakes smell in stereo with their forked tongues, which they flick to create air vortices, pulling in the air from either side. They can also sense the infrared light given off by the body heat of their prey. (Photo: Jean Beaufort, Public Domain Pictures)

YONG: Yeah, so the final chapter of the book talks about this issue of sensory pollution. So that's where we have flooded the world with too much information, too much light in the dark, too much noise in the quiet. And we don't necessarily think of light and noise as pollutants in the same way that we might think of plastics or environmental toxins, but they very much are. When they exist in places where they don't belong, or at times when they don't belong, they can seriously harm the animals around us. They can waylay migrating birds from their paths, they can pull hatchling sea turtles up a beach rather than towards the ocean where they belong. They can distract pollinating insects from the flowers that they ought to be servicing. These are significant problems and I think these are important problems to grapple with, in part, because they are solvable ones. A lot of the ecological sins that we have foisted upon the planet are very hard to undo. You know, if all greenhouse gas emissions were to cease tomorrow, a lot of the future of climate change would be baked in. If we ceased all plastic pollution tomorrow, the plastics that we have already produced would continue to despoil the oceans for decades and centuries to come. But if we switched off a lot of stuff, much light and noise pollution would stop immediately. That's a very rare opportunity for an ecological win, and one that I think we should take up. You know, a lot of the ways in which we can reduce light and noise pollution, switching off lights and noise, reducing the speed of things like ships or cars, are eminently doable. They just require political will to achieve.

Plankton release chemicals when they are eaten by krill, which seabirds such as albatrosses can smell from miles away in order to locate krill to feed on in a seemingly featureless ocean (Photo: Michael Clarke, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: And understanding. So I think one of the big things is that this book really is fun. For anyone who wants to learn something new about something under our noses. And come on, how much fun was this for you? I mean, you were hanging out with scientists in their labs, you were clipping microphones to leaves to eavesdrop on insects, you know. Of course, there's this stuff about getting punched by a mantis shrimp. I mean, wow, how much fun did you have?

Mantis Shrimps can see the visible spectrum, UV light and polarized light with different parts of their eyes (Photo: François Libert, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

YONG: I had an absolute blast. I did about half of the writing and the research before the pandemic began and then finished the second half in the middle of my COVID reporting and, you know, it was like mainlining joy and wonder at a time when I think I certainly, and, I think, all of us, could use a lot more of it. And one of the things I love the most about this topic, the ways in which animals sense and experience the world is that it is so scientifically and philosophically rich. There are truly wonders everywhere you look and sensory biologists tend to often work with, you know, weird creatures that other scientists ignore. So this book is full of common animals and familiar ones, yes, like elephants, whales, dogs, but also strange ones like mantis shrimps and star-nosed moles and naked mole rats. And it's almost like the entirety of the animal kingdom is here and all of it has, you know, rich detail and stories to tell.

BASCOMB: That’s Pulitzer Prize winning author Ed Yong talking about his book “An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us”. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood. You can find a video recording of their full conversation at the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Ed Yong’s website

- Find the book “An Immense World” here (Affiliate link helps donate to Living on Earth and local indie bookstores)

- Watch the full conversation with Ed Yong here

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Glymnopedie No. 1” on Kaleidoscope, High Note Records]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Fern Alling, Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Mark Kausch, Kharishar Kahfi, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Ashley Soebroto, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth