January 28, 2022

Air Date: January 28, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Unprecedented Fires in Patagonia

View the page for this story

Out of control wildfires have been raging in Patagonia on the tip of South America, where until recently fires were rare. Butimported North American species, heat, drought, and dry thunderstorms connected to climate change are altering the natural fire regime. Thomas Kitzberger, a Professor of Ecology at the National University of Comahue in Argentina, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how fire is changing Patagonia’s ecosystems. (13:47)

Warming Climate and Children’s Health

View the page for this story

Children and adolescents are facing increasing health risks from extreme heat, and a new study looked at heat and pediatric emergency department visits and found that black and brown children are especially impacted. Pediatrician Aaron Bernstein, who is the interim director of the Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment at Harvard and lead author in this study, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the implications of the research. (07:32)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

On this week's trip beyond the headlines, Environmental Health News editor Peter Dykstra joins Host Bobby Bascomb to look at indicators of toxic PFAS chemicals in exercise clothing such as yoga pants. Then, the two discuss a carbon capture facility that is emitting far more greenhouse gases than it is taking in. And from the history books, a speech from President George W. Bush when he sang the praises of “clean coal.” (05:19)

“To Fly, To Live:” Osprey of Long Island Sound

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Experience the first flight of young ospreys, a species of hawk known for their elegant dive as they snatch fish from the surface of water. Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender narrates the awkward stretch of their wings and their first, sublime leap outwards. (02:53)

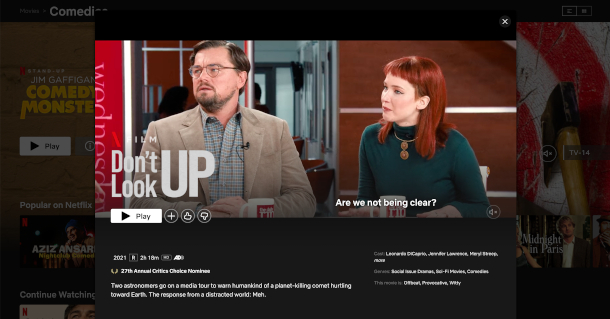

“Don’t Look Up” and the Absurdity of Climate Inaction

View the page for this story

Don’t Look Up, Adam McKay’s newest feature film, uses humor and the metaphor of an impending, Earth-obliterating comet to satirize the ideological denial of climate change that pervades much of our current public discourse. Michael Mann, Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how the film holds up a mirror to the political obstacles to climate action and false promises of future technological fixes. (17:17)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220128 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Aaron Bernstein, Thomas Kitzberger, Michael Mann.

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Invasive species, fire, and climate change are permanently changing Patagonia.

KITZBERGER: We really have to assume that the conditions of the future are going to be different. We cannot have the romantic idea of going back to our 19th century landscape because it's a romantic view which is not going to be very resilient to the future conditions.

CURWOOD: Also, the hit Netflix movie Don’t Look Up as an allegory for climate change.

MANN: "Don't Look Up" is what the forces of inaction -- polluters, and those promoting their agenda, politicians and front groups and conservative media outlets -- they don't want us to look up. Something that's plainly evident, all we have to do is use our two eyes. Well, that's true with the climate crisis, isn't it?

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Unprecedented Fires in Patagonia

Until recently, wildfires only occurred every 500 years or so in Patagonia’s wet forests. Increasing heat, drought, dry lightning, and pine trees originally imported from North America are changing fire regimes and the local ecology. (Photo: courtesy of Thomas Kitzberger)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston. This is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Out of control wildfires are raging in Patagonia, on the tip of South America in both Argentina and Chile. It’s been blazing hot during their summer, with the central part of Argentina reaching a record high of 113 degrees Fahrenheit in mid-January. And on January 12, Argentina’s federal government declared a one-year fire “emergency” because of the ongoing situation. Though the native vegetation for much of the region is a wet forest, major forest fires have become much more frequent in recent decades as the climate changes. Thomas Kitzberger is a Professor of Ecology at the National University of Comahue in Bariloche Argentina. That’s in the foothills of the Andes not far from the recent forest fires, and he joins me now to discuss. Welcome to Living on Earth, Thomas!

KITZBERGER: Thank you for inviting me.

BASCOMB: So can you please describe this region of Patagonia for our listeners who maybe haven't been there?

The Valdivian temperate rain forest ecoregion extends along western Patagonia from roughly 37° to 48° South latitude in both Chile and Argentina. (Photo: Mari L. Peña, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

KITZBERGER: Well, we are in a, in a forested region. These are southern temperate forests. These are evergreen trees, very different from the North American coniferous forest, that strive along the Andes, on both sides, from Chile and in Argentina. And they are basically fed by the rains that come from the Pacific Ocean, generating different kinds of forest like rainforest, Southern conifer forests, shrub lands, and finally the Patagonian Steppe, which is a grassland. There is an important rain shadow effect of the Andes, on this Pacific moisture that comes in, it’s just very similar to what happens maybe in Washington State, where you have the Cascades and the rain shadow, it's very similar. So it's like a, like a mirror of the Northern Hemisphere, but with very different species, species that are not really very adapted to fire. So, it is a, it is a fascinating region of the world.

BASCOMB: Well, it sounds just stunning, it sounds amazingly beautiful. But what has it been like there recently in terms of heat and fires?

KITZBERGER: Yeah, we are witnessing now very strong changes due to climate change. We are witnessing a 50-year-long trend in drying and in warming; we are experiencing hot spells. We are experiencing thunderstorms, which were not very common in this region in the past; mortality of forests, even without fire, trees die off due to drought. And of course, very large fires in recent times. So we are very concerned about those changes.

Planes from the Bariloche firefighting brigade fighting a forest fire near Lake Nahuel Huapi on January 3, 2015. (Photo: Mariano Srur, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: How natural is fire in this region of Patagonia? What do you see in, you know, the longer history?

KITZBERGER: Well, the long history tells us that the fire was a disturbance in the forest, but it was not a frequent disturbance in the forest. So there could be eventual lightnings, there could be eventual volcanic eruptions, we have a lot of volcanoes here. And there could be also Indigenous people burning the forest. But these forest fires were generally smaller, and less frequent. So if you go back in time, and you reconstruct fire history of, of the wet forest, you could have fires every maybe 500 years. And this is completely compatible with the existence of these kinds of forests, these kinds of species that are not very well adapted to fire. But still, if the fire is not very frequent, very large trees, you know, a mature forest can withstand fire because the trees are very large. And some of the trees survive the fire and they create a new generation of trees that can strive until the next fire every 300, 400, 500 years. The problem is that under new climatic scenarios, the forest will burn more frequently, if the ignition is there. And the ignition is there now, you know, because there are more people and there are more lightnings.

Lake Nahuel Huapi is the largest of many lakes in Argentina’s Nahuel Huapi National Park, which surrounds the city of San Carlos de Bariloche. Forest fires have been burning in the park and the region during the 2021-2022 summer season in Patagonia. (Photo: David, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: So tell me more about that. Why is there more lightning now in Patagonia, what's going on with climate change that's contributing to just the right conditions for more fire?

KITZBERGER: Well, this is something we have detected in the past 10 years, we have first looked at the number of lightning-ignited fires that were reported in historical documents. And we have noticed that since the 1980s, 1990s, the number of lightning-ignited fires that were reported has tripled compared to the previous period from the 1950s to the 1970s, which is correlated with increases in temperature of the summer. So we have, we're having hotter summers, drier summers, and summers that are more prone to thunderstorms. And these thunderstorms are related to a change in the circulation of the subtropical air masses that come from the Amazon and from Northern Argentina, from Paraguay. And they are funneled in from the north to the plains of the Andes, as far south as Bariloche and even farther south. I think that previously this climatic pattern was not very common because in general what we have is westerly circulation of wind, and the westerly wind is generally very stable and does not produce lightning. So when you have a Pacific storm coming in, it doesn't carry lightning. Whereas when you have a northerly wind coming in, it is very unstable air. So and this produces generally these dry thunderstorms which are so dangerous in our region because they don't produce much rain, but they produce lightning. And if that combines with a drought, the probability of ignition of a lightning, that it ignites a fire, is very high.

BASCOMB: Yeah, seems like a very good scenario for creating fire. And I understand that there is a monoculture of pine trees that were planted there decades ago for timber. How do they factor into the fires that you're experiencing?

KITZBERGER: Yeah, it's not a very good combination, because these plantations were promoted by the Argentinian government during the 1970s and 1980s. And they were promoted by subsidies. So the owners of the land were given money to plant pine trees. Ponderosa pine; Radiata -- Pinus radiata; Pseudotsuga -- Douglas fir; Lodgepole pine; all these trees that are northern hemisphere conifers, generally from North America. And you already know these are very flammable species, they have high content of resins, of volatiles in the leaves, they burn at very high intensities. So these species were planted for many, many years in Patagonia. And many of these plantations were later abandoned, unfortunately. They were abandoned because -- this is bad policy. There was not really a market for this wood, the wood was not very high quality. So the plantations were abandoned because the money was already cashed in. The government paid for the seedlings, they didn't pay for the, for the mature trees. So once the plantation was established, the plantation was not taken care of. There was no thinning. So these trees are loaded with dry fuels. And the other problem is that some of these species are very invasive to our native ecosystems. So what has happened during the last three to four decades, is an active invasion of conifer trees into native ecosystems. And these trees are capable of establishing under the canopy of the native trees. And they create what we call novel ecosystems. These are novel combinations of native trees with conifer trees. And the problem is, when a fire sweeps through that invaded native ecosystem, the dominant tree after the fire sweeps through the forest will be the exotic conifer.

Ponderosa, lodgepole, and radiata pines are among the fire-adapted North American species that have been invading Patagonian forests and creating what ecologists call novel ecosystems. (Photo: Katja Schulz, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: You know, I've read personal accounts of people that that survived the fires there, and they say these massive pine trees just went up -- [SNAPS FINGERS] you know, like that, just in minutes, they were just in flames and practically gone, you know, immediately, it was just; they burn so quickly.

KITZBERGER: Yeah, they have adapted for millions of years to burn very hot, the conifers. But they, at the same time, they have created their own adaptations to, to repopulate the area afterwards. So the serotinous cones, which open with the heat, and many other adaptations like very thick barks to resist the fire, and so on. And some of the fire policies that are being applied in Patagonia come from the fire science ecology school of North America. And the problem is that you cannot translate, really, the policy of fire of North America to Patagonia, because the species behave very differently. For instance, in North America, the more time you, you wait to a forest to mature, the more flammable the forest will be. And this has created the idea of prescribed burning to reduce the flammability of the forest. Here in Patagonia, it's absolutely the reverse. When you burn a forest, you create a shrubland, and the shrubland is more flammable than the forest. So prescribed burning would create the, the opposite effect here in our forests than in a coniferous forest.

The view from mountain Cerro Campanario in Nahuel Huapi National Park, where fires have been burning during the 2021-2022 summer season in Patagonia. (Alexander Shchukin, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Professor Kitzberger, to what extent is Patagonia experiencing a new normal in climate? What do climate scientists tell us we should be expecting in that region in the coming decades?

KITZBERGER: We are already in a new normal, and the global change models all agree that the region will experience at least a reduction in 20 to 30% in rainfall. And this is not for the most pessimistic scenarios, but for a very probable emission scenarios; and an increase in temperatures of two to three degrees Celsius. And our fire probabilities, or frequency, could increase two to three fold during the mid twenty-first century and six to eight fold during the late twenty-first century, which is really disastrous for our ecosystems.

A Patagonian forest after a fire has swept through (Photo: Javier Grosfeld)

BASCOMB: How does it feel for you as a scientist to be living there and documenting these changes and at the same time, see so little action, you know, to get to the root cause of things?

KITZBERGER: I started studying fire in this region 35 years ago. I was very young. And the first [LAUGHS] reaction of people, when I was saying I was studying fire in this region is, "Why are you studying fire? There is no fire in this region." And the perception of fire is very dependent on the events. I don't know if that happens in North America too. But during years of very little fire, people lose interest in fire. But then a very big fire year happens and everybody's very worried. But then they lose interest very quickly. That has been my, my impression for many, many years. And the changes in society are very slow, I would say, but they are still there. I think young people, when I talk to very young people, they are very aware now that this is a problem that has an underlying problem of climate change. And the actions that we have to do occur at very different levels, from the individual actions to the government actions. So Argentina is very, very slow also in complying with international treaties on emissions, like many other countries in the world, they are very slow --

BASCOMB: I was gonna say, it's not just Argentina! [LAUGHS]

KITZBERGER: [LAUGHS] So yeah, my general feeling, to answer your question is a little bit of frustration with the politicians. But with a lot of hope of the new generations, of young people.

A photo taken in Torres del Paine National Park, which is part of Chilean Patagonia, shows a burned-out forest transitioning to shrubland. (Photo: Murray Foubister, Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: I bet you hope that you had been wrong in your choice of career, you know, if you go back 35 years, and say oh, I should have gone into something else. There's no fire here. They were right! [LAUGHS]

KITZBERGER: [LAUGHS] Well, when I started biology, I am a biologist as an undergrad, I was going to be a marine biologist. But I guess, in marine biology, very similar things occur too, to the marine biologists. They are now worried, very worried about plastics, they're worried about warming, they are worried about acidification. So everywhere you look at there are problems.

BASCOMB: With such a dramatic increase in the fires there in Patagonia already, what solutions might there be to prevent these fires, to make the native forests more resilient, or, you know, to ameliorate the situation?

Thomas Kitzberger is a Professor of Ecology at the National University of Comahue in Bariloche, Argentina (Photo: courtesy of Thomas Kitzberger)

KITZBERGER: Yeah, there are many aspects that we can work on. After the fire, we can work on restoration, not necessarily to go back to the original condition, but to go into a new landscape that maybe is more resilient to the next fire. So we are thinking of things like reforesting, or doing restoration with species that are less flammable, that are more resilient to fire -- native species, I mean. So our species that are more adapted to warmer conditions. So we really have to assume that the conditions of the future are going to be different. We cannot have the romantic idea of going back to our nineteenth century landscape because it's, it's a romantic view, which is not going to be very resilient to the future conditions.

BASCOMB: Thomas Kitzberger is a Professor of Ecology at the National University of Comahue in Bariloche, Argentina. Thank you so much for taking this time with me today. I really enjoyed our chat.

KITZBERGER: Oh, it was a pleasure. Lovely. Thank you very much for inviting me.

Related links:

- National Geographic | “An imported tree fuels Patagonia’s terrifying summer fires”

- Latin American Post | “Valdivian forest: a biogeographic island that was saved from the glaciations”

- Learn more about Thomas Kitzberger’s research

[MUSIC: Yann Tiersen featuring Stephen O'Malley, “Introductory Movement” on Portrait, by Yann Tiersen, Mute Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up –The warming climate is leading to increasing health problems for children. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Carolina Chocolate Drops, “Mahalla” on Leaving Eden, by Hannes Coetzee/arr.Dom Flemons, Nonesuch Records]

Warming Climate and Children’s Health

Extreme heat can cause dehydration, heat exhaustion, heat strokes and increase intestinal bacterial infections amongst children. (Photo: Michael Rabodin, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Over the past three decades excessive heat has been the number one weather killer in the US. And in Europe some 35,000 people died during a blistering heatwave in 2003, mostly the elderly. And as the climate warms, infants, children and adolescents are also facing increasing health risks, according to new research. Fortunately, children rarely die during heat waves, but scientists found emergency department visits for children at 47 US hospitals went up almost 12 percent during the warmest months of the years studied. The research was published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, and its lead author is Pediatrician Aaron Bernstein. Dr. Bernstein is the interim director of the Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment at Harvard, and he joins us now. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

BERNSTEIN: Great to be with you again, Steve.

CURWOOD: So what sorts of health issues were observed in your study? In other words, what's the primary reason for the emergency department visits?

BERNSTEIN: Some of the things we saw were entirely unsurprising. Heat-related illnesses, what we call heat exhaustion, heatstroke, go up with heat. And the hotter it gets, the more likely those visits are. But a lot of the other things might not be immediately obvious. And one good example of that are certain kinds of bacterial infections. So we saw greater visits for bacterial intestinal infections.

CURWOOD: You're talking about, you know, glorified upset tummy or diarrhea? What are we talking about?

BERNSTEIN: Yeah, so these are bacteria that often are on food, spoiled food, that cause diarrhea and vomiting. And you can imagine that in warmer months, people are more likely to have a picnic, let food spoil, you know, you don't fully cook the hamburger on the grill. And we also know that warmer temperatures promote bacterial growth. Now, one of the things that is important to note here is that we see stark differences in rates of visits based upon whether a child had private insurance or public insurance and whether they were a white child or a racial or ethnic minority child. And those differences reflect what we know, which is that many children who are either on public insurance or of a minority status are more likely to use an emergency department in general, because they lack access to the primary care offices and other resources that might prevent them from being seen. So we saw that with the bacterial intestinal infections, we saw it, in fact, in many other of the conditions that we saw increased rates for including things like, you know, ear infections and skin infections. Interestingly, we also find that, you know, injuries and poisonings are more likely with higher temperatures as well. So we find a suite of effects. And often we see greater rates of visits for minority children.

CURWOOD: Which illnesses were you most surprised to see show up in your study of the heat effects on children?

Our @HarvardCCHANGE new study lays bare the inequities that children face w/ extreme heat.

— Dr. Aaron Bernstein (@DrAriBernstein) January 20, 2022

I spoke to @WinstonC_S @nytimes about the potential lifelong impacts climate change can have on our kids' health: https://t.co/Nca4TquIJW

BERNSTEIN: The one that surprised me the most was that we saw increased rates of visits for blood and immune system disorders. That's a pretty broad group of conditions you some of them are things like anemia, so not having enough red blood cells. That includes things like immunodeficiencies. Heat isn't causing immunodeficiencies. But children with immunodeficiencies are probably more at risk for those same infections we were talking about before. But this is a finding that I think really warrants some further investigation, because I have a pretty good mind as to how we would see more ear infections or more bacterial intestine infections, more skin infections, more accidents, you know, greater visits for children with diabetes, but I'm not sure I really understand this piece. And if it turns out that there is some way in which heat is affecting risk for those children, that would be something that I think is potentially new and concerning. So I think that was perhaps among the more surprising findings for me.

CURWOOD: Now what about mental and behavioral health?

BERNSTEIN: So if you look at the whole population of children in our study, we didn't see a significant effect of heat on those conditions, although it's very close. But when we divided the group of kids into white children and children of minority status, there is an effect and a substantial one. And the children who are you know, Latino, Black American, Asian American, etc, are much more likely to show up in emergency departments for those problems. Do I think that's because white children aren't getting those effects from the heat? No, I think it's because white children have better access to care. And this is what I mean when I talk about the effects of heat amplifying the inequities we see.

CURWOOD: So Ari, What should parents and other caretakers of young people think about when it comes to heat?

As the climate crisis intensifies heat, Dr. Bernstein recommends that parents and caregivers be aware of health risks during warmer months. (Photo: Edward M Johnson, U.S. Army, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BERNSTEIN: Well, I think the first is, is that when it gets warm outside, you should definitely, if you can, have your child playing outside. This is not a study to say, let's be worried about the heat generically. This is a study that tells us that, you know, heat does matter to children, it especially matters to children with certain chronic medical problems. And that, you know, with that knowledge, we can do stuff to make sure that our children can play outside when it's hot out, safely. And a good question of a parent is, well, what is too hot? And the answer is, well, it depends on where you live, because 80 degrees in Boston is not 80 degrees in San Antonio. What really matters is the percentile of temperature. How hot is today as compared to the usual? And fortunately there are more resources that are coming online to give parents and providers that information. We're starting to see heat forecasts that tell you, you know, this day is going to be in the 85th percentile of temperature, which is a signal to those people who are at risk, you should be mindful of those heat concerns, maybe offset your activities, maybe make sure you're well hydrated, or whatever the reasonable action is.

CURWOOD: So what can your study teach us about ways to provide better health care access to children and teens?

BERNSTEIN: Yeah, well, the first thing is it underscores a whole body of work that says we absolutely need to provide better health care to the least fortunate children in our country. I mean, children on public insurance uniformly have higher rates of ED visitation, that reflects the broader trend that those children do not have access to primary care. The reasons they often do not are because of insurance. And that in many places, many providers do not take public insurance and/or that those children are maybe more likely to move and move from one place to another and having established primary care is harder. But you know, if we had access to health care for any child, the barriers to access are much less and that makes it so that whatever conditions the child may have, that may put them at risk for heat-related illness are addressed. It means that if a parent is concerned, they can call that office, get some guidance before the kid lands up in an emergency department. And I think that's one of the key messages that we see in this study about what it means more broadly for the health care system.

CURWOOD: Aaron Bernstein's a pediatrician and Interim Chair of the Center for Climate Health and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Bernstein, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

BERNSTEIN: Nice to be with you as always, Steve.

Related links:

- Learn more about the study led by Dr. Bernstein titled Summer Heat and Children Emergency Department Visits

- USA Today “'Code Red' Heat: The climate emergency is sending more kids of color to the emergency room”

- New York Times “New Research Shows How Health Risks to Children Mount as Temperatures Rise”

- Learn more about Dr. Ari Bernstein

[MUSIC: Back of the Moon, “Voodoo Chilli” on Luminosity, by H.Napier/A.Hutton, Mad River Records]

Beyond the Headlines

8 out of 32 pairs of leggings and yoga pants tested showed indicators of fluorine, which itself is an indicator of toxic “forever chemicals” known as PFAS. (Photo: Nenad Stojkovic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, it's that time in the show again for a trip beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Bobby. There's an investigation that found possible evidence of PFAS in workout gear and yoga pants.

BASCOMB: Hmm, and PFAS chemicals, I mean, those are called forever chemicals. They can live in the body for a long, long time and cause a lot of health concerns including cancer, from what I understand.

DYKSTRA: There's strong indications that they're a cancer risk. I should say up top, this study was published and partially funded by my organization, EHN.org. EHN partnered with a health-based website called Mamavation. And Mamavation tested activewear and found levels of fluorine, which is in turn an indicator of toxic PFAS chemicals, that went up to 284 parts per million. They tested 32 different kinds of active wear and yoga pants, and eight had detectable levels out of a total of 32.

BASCOMB: Well, I have to say, I mean, leggings and yoga pants have sort of become the uniform of people who work from home and you know, don't have to go to an office anymore. This is pretty bad news.

DYKSTRA: Oh, I'm never seen without my yoga pants. That's a joke, folks.

BASCOMB: Well, that's certainly bad news. What else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: We're going to go to the tar sands of Alberta, and a plant downstream from the tar sands, actually in Saskatchewan, that is intended to be a carbon capture and storage facility, taking those tar sands absolutely loaded with greenhouse gases. And right now, in a study by the NGO Global Witness, that plant was found to have removed 5 million tons of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. That sounds kind of impressive. But what Global Witness found is that it took 7.5 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions to save 5 million—not a very healthy ratio.

Alberta Minister of Energy Diana McQueen and Conservative MP Mike Lake tour the Quest Carbon Capture and Storage facility in 2014. (Photo: Chris Schwartz, Government of Alberta, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: So it costs two and a half million tons then of greenhouse gas emissions to run this facility. Doesn't seem like a very good deal.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, it sounds like one step forward and two steps back, and out of that 7.5 million tons of emissions from the carbon capture facility, much of it is methane. Methane is 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide during the first 20 years of methane's existence in the atmosphere. And it accounts for about one quarter of all manmade emissions impacts on our climate.

BASCOMB: Hmm. Well, this carbon capture storage facility in Canada, I mean, it's not the only one in the world. There's plenty of these all over the place, including the United States, of course. Do we have any idea if it's a similar scenario in other facilities, you know, one step forward, two steps back, as you say?

DYKSTRA: Well, there have been similar failures. There's the Kemper facility, which about five years ago, collapsed under the burden of $5 billion expenditure and little to show for it. Around the same time, there was the Department of Energy Project in the state of Illinois, that was suspended after going 2 billion in the hole in attempting to make carbon capture work. It's even working its way into the current budget impasse between the Republicans, the Democrats, and Democratic Senator Joe Manchin from West Virginia, who, while opposing some of what's in the Build Back Better Bill, wants to include carbon capture and storage, something that he feels would help prop up the coal industry in West Virginia.

BASCOMB: Well, maybe somebody should send Senator Manchin this report and see if you know, maybe we'll turn things around in the future here.

DYKSTRA: A little too late to send him a lump of coal for Christmas.

BASCOMB: Well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

In a speech in January of 2002, President George W. Bush praised coal and “enhanced technologies” to make coal burn cleaner. (Photo: Eric Draper, White House, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: Also dealing with carbon capture storage, on January 24, the president at the time was George W. Bush. He spoke in Charleston, West Virginia, and told the West Virginians eager to hear good news about the suffering coal industry, that carbon capture storage is part of his future. And this is what he said: “In order to become less dependent on foreign sources of energy, we've got to find and produce more energy at home, including coal. I believe that we can have coal production and enhanced technologies in order to make sure that the coal burns cleaner. I believe we can have both.” 20 years later, carbon capture storage is nowhere with a lot of money spent on efforts to make it happen.

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. All right. Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website, and a picture of Peter Dykstra in those leggings that he promised us.

DYKSTRA: No, there isn't.

BASCOMB: Oh, come on. All right. We'll talk to you soon, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot, Bobby. Talk to you soon.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “Investigation Finds Evidence Of PFAS In Workout And Yoga Pants”

- Vice | “Shell’s Massive Carbon Capture Plant Is Emitting More Than It’s Capturing”

- Read an excerpt of President Bush’s speech in the White House archives

[MUSIC: Mongo Santamaria, “Bonita” on Brazilian Sunset, by Mongo Santamaria, Candid Records]

“To Fly, To Live:” Osprey of Long Island Sound

A young osprey chick raises its narrow wings in anticipation of its first flight out of the nest. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Not all siblings are born equal. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender watched his local osprey nest.

Osprey of Long Island Sound

To Fly To Live

Hammock River Saltmarsh

© 2021 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

Three young osprey move about. They are tired of the nest. Its narrow world. Their portion of confinement these long months. It has not rained and it will not rain. Only the saturated heat of August pours down, full force, even at this early hour. The sun clears the tree line. Discomfort grows. Perhaps that is the ultimate stimulus.

It is a rustic show. Flapping and slapping, ungainly. They side-slip and bounce and stumble, hardly an act of grace. When more than anything Grace is what they need. And then by accident and for an instant only -

Up!

And so it begins.

Gravity in surcease.

The Surly Bonds release.

And in the instant every No is Now!

Yes! Yes! What Wings can do.

They are a crowd before the main event, the performance late -

And One and Two and…

Two and Three and …

The sisters are stronger. Their wings broader. Their heights are higher. Their leaping is longer. Born before their brother, female and by nature of greater heft and girth, they have matured. He has not. Those few days? Such an advantage in that small head start.

And One and…

Two and…

Gone!

The father returns to the nest gripping a menhaden’s tail. Unable to wait, one of the chicks opens its beak to take a bite. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

The sisters head off in opposite directions, their brother left behind. His thin chest. His scrawny legs. Inadequate in every way. The harder and faster he flaps the more he founders. He cannot get the hang of it and the effort tires him and only makes him more, incapable. The sisters return. He continues. They watch him in his futility.

Mid-afternoon, their father lands in the nest, a menhaden in his talons. The brother sits sunken into his shoulders. His mother looks at him. With her beak she tears a small piece from the fish. Turning her head sideways to make it easy for him, she puts it into his mouth. Then another.... Bit by bit. Feeding him, like a baby. The sisters stand aside. All of them, his mother, father, the two sisters, all of them want for him what they want for themselves.

To Fly. To Live.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Read Mark's corresponding field note for this essay

- Mark Seth Lender’s website

- Information about ospreys

- New Jersey Osprey Project (Osprey Conservation):

- Special thanks to Destination Wildlife

[MUSIC: Adriana Maciel, “Samba Dos Animais” on Brazilian Playground, by Jorge Mautner, Putumayo Kids]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Don’t Look Up! We’ll have a chat with climate scientist Michael Mann and his take on the hit Netflix movie poking fun at climate denial. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Key West” on Electric Spirit, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

“Don’t Look Up” and the Absurdity of Climate Inaction

“Don’t Look Up” set a Netflix record for most views in a single week and has become the second most-watched original movie in the company’s history. (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” page on Netflix)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Climate fiction just got a huge boost of star power with the film Don’t Look Up. It’s headlined by Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence, Tyler Perry, Meryl Streep, Cate Blanchett, and Ariana Grande. It’s about a pair of scientists who discover a massive, “planet-killing” comet hurtling towards Earth with just 6 months until impact. They try to sound the alarm to get a distracted world and self-serving people in power to do something about it. In this scene they are explaining the severity of the situation to a skeptical president of the United States.

Dr. Oglethorpe: Madam President, this comet is what we call a planet-killer.

Dr. Mindy: That is correct.

President: Mmm-hmm. So how certain is this?

Dr. Mindy: There’s 100% certainty of impact.

President: Please, don’t say 100%.

Aide: Can we just call it a potentially significant event?

Jason Orlean: Yeah, yes--

Kate Dibiasky: But it isn’t potentially going to happen. It is going to happen.

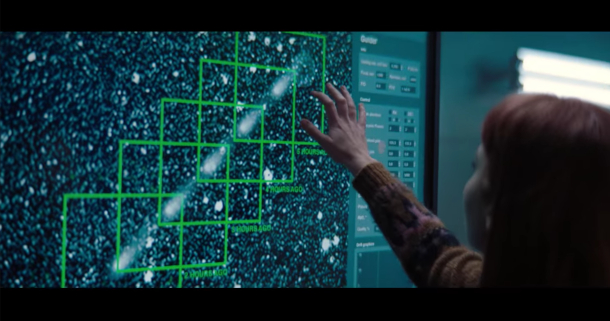

Jennifer Lawrence’s character, PhD student Kate Dibiasky, maps the comet’s trajectory towards Earth. (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix)

Dr. Mindy: Exactly. 99.78% to be exact.

Jason Orlean: Oh great. Okay, so it’s not 100%.

Dr. Oglethorpe: Well, scientists never like to say 100%.

President: Call it 70% and let’s just move on.

CURWOOD: Of course, the comet is an allegory for climate change. And no spoilers here, but we do want to talk about the film’s message and what it represents for some frustrated climate scientists. Joining me now is one such scientist. Michael Mann is a Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Michael.

MANN: Thank you, Steve. It's always good to be with you.

CURWOOD: So Michael, this is a very dark film in one sense, but it's also intensely funny at times. How was the writer and director Adam McKay able to harness humor to talk about something as terrible as the climate crisis?

MANN: Well, I think that's the challenge. And I'm a big fan of Adam McKay and his films, they're just hilarious. And David Sirota also had a hand in helping write the story. And I think that they really pulled it off, right, which is to both communicate the gravity of the threat, the underlying threat that we're really talking about, because it's a metaphor for the climate crisis even though it's framed as a comet that's about to strike Earth. But to do it in a way that, first of all creates some distance, because there is so much ideological baggage now that people come into the climate discussion with. And so if you talk about climate sort of straight up, you're going to sort of lose some of your audience, you're going to raise their hackles; you know, climate change denial has become ideological among some. And so if you make it about something completely different, but the undertones and the message really are sort of informing their understanding, hopefully, of the climate crisis, then maybe you can get some people to listen, to open up their ears. As I like to say, the front door is bolted shut; you know, climate change denial is a firm sort of part of the ideology of the American right today. So the, the front door is closed, you can't just barge through with facts and figures. So you look for that side door. And I think humor and satire is that side door and that, and that's what they've done here.

“Don’t Look Up” director and writer Adam McKay at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2019 (Photo: Harald Krichel, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Yeah, you know part of the issue is, how do you avoid getting onto that slippery slope of urgency into “doomism”? How did, how did this movie succeed in doing that?

MANN: Yeah, and you've hit on, you know, the key point here, and this is a point that I emphasize in my recent book, The New Climate War, is, you know, the importance of communicating both the urgency, but at the same time, the agency: the fact that it's not too late to do something about the problem. And you know, there is the danger that some people will come away from the film with the wrong message, because it's possible to come away from it, and think, "oh, wow, we're doomed, that's really the message of this film." But that isn't the message, if you sort of think more about how things unfold, and I don't want to sort of spoil the film for your listeners who haven't seen it yet. But suffice it to say that there was a path forward that was safe and reliable. And that's the path that wasn't taken, right. And so without giving it all away, if they had addressed this problem in the way that scientists said it needed to be addressed, then there was a real chance for, for success, but instead, sort of, they listen to the voices of tech billionaires. And that led us down the wrong path. And, and that's, I think that's the critical message. We're at a juncture. There's the right path forward, and there's the wrong path forward. And the movie shows us what happens with the wrong path.

CURWOOD: Indeed, and the techno-billionaire they have there, what is this, a send up of, is it Elon Musk? Am I looking at Bill Gates? Am I looking at Jeff Bezos, is it Mark Zuckerberg -- who am I looking at in this character?

MANN: Yes, yes, all of the above! [LAUGHS] I think it's an amalgamation of all of those individuals. And you can literally see pieces of each of them in the character, the way that social media information that we provide is used for profiling and targeting us, that's in there. But to me, what was really significant was this idea that we can engineer our way out of the crisis. And to me, this was an extended metaphor, or an allegory or whatever you want to talk about, clearly, for the climate crisis. And it was also communicating the dangers of sort of thinking that we can just invoke some techno-fix down the road, as a way of sort of denying the actions that we need to take right now, while we still can.

In the Oval Office, Dr. Randall Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio) tries to explain the comet Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence) has discovered is headed straight towards Earth, alongside Dr. Teddy Oglethorpe (Rob Morgan), head of the Planetary Defense Coordination Office. (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix)

CURWOOD: I mean, they say that this comet could make trillions of bucks for this guy, and essentially saying that people in these positions of power think it's worth risking the entire planet, to get it out and bring it to market. Kind of like the fossil fuel reserves that are sitting around, that must stay in the ground if this planet is to remain habitable, huh?

MANN: No, absolutely. This idea that we can continue to burn fossil fuels because look, we will just find a techno-fix down the road -- "Trust us!" So, you know, we hear a lot about geoengineering, and there are some scientists, and even Bill Gates is actually financing research into these massive planetary interventions like shooting sulfur dioxide particles into the stratosphere to block out some of the sunlight, to try to cool the planet back down. And the more you look into these potential interventions scientifically, the more you realize there are all sorts of potential unintended consequences. That's one fundamental problem. But even more problematic, I would say, from the standpoint of the politics and the policy, it provides a convenient argument for delay. It's a crutch for polluters who want to say, hey, look, we can solve this problem down the road. So let's continue to burn fossil fuels and generate economic growth, because we'll figure out how to solve this problem later -- "Trust us!" But even some of the other seemingly more moderate geoengineering approaches, like massive carbon capture, where we sort of suck the carbon back out of the atmosphere. Well, we're fighting the laws of thermodynamics and economics in trying to do that, it would be hugely expensive, it's unclear that it can be done at scale. But it's being used by some polluters, again, as this crutch. And we've got to cut our carbon emissions by 50% within this decade to avert catastrophic warming. We're not going to do that with new breakthrough technology, we can solve this problem using existing renewable energy, there are plenty of studies that demonstrate that, the obstacles aren't technological at this point. They're entirely political. It's really that simple.

A distracted President Janie Orlean (Meryl Streep) receives the news about the comet headed straight for Earth. (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix)

CURWOOD: All right, Michael, so where do you think this allegory breaks down? And in your view, how well does it, does it work to get this message across do you think?

MANN: I think it works in the sense that it's so distant from the climate crisis, that like I said before, it doesn't come with that same ideological baggage. I would like to think we could all band together today, Republicans and Democrats alike, and agree that we need to do something about an imminent planet-killing comet, right? We would hopefully all, you know, band together and the fact that we don't, that even with something as clear-cut as that it devolves into politics and greed. And, and so all metaphors are imperfect by design. And, you know, this metaphor is imperfect in the sense that it's sort of a discrete event. We don't go off a cliff at three degrees Fahrenheit warming of the planet. What we're doing instead is we're walking out onto this minefield. And the farther we walk out onto that minefield, the more danger we encounter. So there's an imperfect translation of, you know, the metaphor to the climate crisis. At the same time, we can say that, you know, three degrees Fahrenheit warming is really bad. A lot of bad things will happen if we exceed that amount of warming, it's something we really want to try to avoid at all costs. So the binary nature of the disaster isn't a perfect parallel with the climate crisis. But the idea that there are thresholds that we need to avoid, and we need to take action now to avoid them, translates reasonably well, I think.

CURWOOD: So Michael, I've got to ask you this. I mean, to what extent do you envy the certainty that the scientists in this movie have about, you know, the discovery here, it's going to hit the planet in exactly six months and 14 days. Very convenient for them.

MANN: [LAUGHS] Yeah, that's right. I mean, it's an exact prediction that can be tested by a single event, right? Whereas climate science is a much more complex sort of science in the sense that it isn't just a single event that we're trying to predict. It is a massive number of unfolding events and amplified events, and sometimes subtle linkages between the warming of the planet and all the various impacts that that is leading to. It's not quite as direct and immediate and acute, as you know, a comet that's about to strike us. And yet, when it comes to the bottom line, there's a remarkable similarity. It's that ideology has been used to divide us and to favor an agenda of inaction, that, in the case of the film, costs us the entire planet. But in the case of climate change, if we fail to rise to the challenge, it will cost us a livable planet.

CURWOOD: Indeed. And you know, the funny thing about the precision though: back in the 1960s, Exxon Mobil and those folks had a pretty good clue. By the '70s and '80s their predictions are playing pretty much right out to where CO2 levels and temperatures are these days.

MANN: You're absolutely right, Steve, it's, it's, it is remarkable that, you know, when we talk about all the different impacts of climate change that gets into subtleties and complexities, but if we just stand back and look at the big picture, the warming of the planet, it's actually exactly as was predicted a half century ago by none other than Exxon Mobil, the world's largest publicly traded fossil fuel company. Their own scientists successfully predicted both the rise in carbon dioxide concentrations, if we remained addicted to fossil fuels, the rise that we would see by now, and the warming that that would cause. And so even as Exxon Mobil's PR apparatus was attacking independent climate scientists and attacking climate science publicly, their own scientists were delivering the same fairly precise message.

Jennifer Lawrence’s character Kate Dibiasky loses it on live television when the anchors try to downplay the news that a “planet-killing” comet is on a collision course with Earth. (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix)

CURWOOD: Hey, by the way, Michael, you have a connection to this film, huh?

MANN: [LAUGHS] Yeah, it's sort of funny. So I would have liked to have attended the premiere, I was invited to attend it. But the logistics of making it to New York City made that, you know, in the era of COVID, made that really difficult. And my, my daughter was, was very disappointed because she was looking forward to attending it with me in New York City. So instead, the Netflix folks were nice enough to send us a link so we could watch the film in advance, in the comfort of our home. And so we're watching this film, and I don't know, maybe it's 30 minutes into it or so as we're meeting, you know, we're getting to know Leo, Leonardo DiCaprio's character, Dr. Mindy, the astronomer, who's, you know, whose graduate student, really, and he have discovered this comet. And Leo's, you know, mannerisms and just the way he speaks -- my daughter said to me, "I think he's basing this on you" --

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

MANN: -- And I sort of laughed that off. I mean, I've gotten to know Leonardo DiCaprio pretty well, I've, you know, corresponded with him on a number of occasions, helped advise him on some projects. And, you know, at some level, we've sort of become friends. But I didn't really, it didn't occur to me that that might be the case. I sort of laughed that off until, I guess it was a couple of weeks later, there was an interview with Leo, that aired, and in it he named-checked me when he was talking about sort of what inspired the character in the film. And I didn't know how to take that. Because if you watch the film, and again, I won't give it away -- Leo is a flawed character. You know, in the end, you know, I would put him on the side of hero, but he's a flawed hero. And some of those flaws, I would hope, aren't commentaries on me specifically, especially the marital infidelity! [LAUGHS] My wife sort of looked at me askance as soon as, you know, that connection was made. So, you know, I think what, what Leo was trying to embrace was the frustration that we climate scientists feel in trying to communicate this, this threat to, you know, the public, but facing this massive headwind of misinformation and, and sort of the way that the media often doesn't really treat these issues with the seriousness and the urgency that some might hope. Of course, Living on Earth being the obvious exception to that! [LAUGHS]

The astronomer Dr. Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio) has an emotional meltdown on a morning news show hosted by Jack Bremmer (Tyler Perry) and Brie Evantee (Cate Blanchett). (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix)

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, I had to laugh out loud at some of those TV sequences, because, you know, network TV will frequently, yeah, if they brought on a serious scientist, maybe the next thing is, you know, a dancing chimp or something.

MANN: [LAUGHS] Right!

CURWOOD: They just don't... But, and I do hope that the character, Dr. Randall Mindy, wasn't entirely based on you because, you know, at one point, he gets so frustrated with the lack of urgency that he absolutely loses it and has a meltdown on live television in this film. And, and also, the Jennifer Lawrence character has a similar situation. I guess you've probably never really melted down like that on television, but -- but how close have you come?

MANN: [LAUGHS] Yeah, you know, I think he goes through this sort of rapid media training, they recognize he's going to be doing the media circuit. And so they sort of try to train him. But he goes off script at one point and does have this meltdown. And suffice it to say that I think all of us who are climate scientists, but have also engaged in efforts to communicate the science at one time or another, have experienced some of the same frustrations. But we've resisted, at least heretofore, [LAUGHS] --

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

MANN: -- thus far, so far, it hasn't happened to me—an on-air meltdown. But I thought that it was a clever way of just saying, Look, people! We have to confront that this really is a crisis, we can't continue to tiptoe around it and, and treat it as if it's just part of the entertainment ecosystem. This isn't just about entertainment and communication, it's about, you know, addressing the greatest threat that we as a civilization have addressed. And in the movie, it's a comet; in the real world, it's the climate crisis.

Dr. Michael Mann is a Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University and has been an advisor to Leonardo DiCaprio about climate change. (Photo: Joshua Yospin)

CURWOOD: And before you go, Michael, comment on the title of the film.

MANN: Don’t Look Up [LAUGHS]. Well, you know, "don't look up" is what the inactivists, as I call them in The New Climate War, the forces of inaction, polluters and those promoting their agenda, politicians and front groups and conservative media outlets. They don't want us to look up, something that's plainly evident. All we have to do is use our two eyes, and we would see it. Well, that's true with the climate crisis, isn't it? We're watching it play out in real time now, in the form of these unprecedented extreme weather disasters. All we have to do is just look out at what's happening. And so I think that's the commentary. And of course, there's the movement that arises among the denialists in the film -- "don't look up." Don't, you know, don't open your eyes. Pay no attention to these massive, costly weather disasters that are playing out now in real time. That's sort of what the forces of climate inaction are telling us.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State. His latest book is called The New Climate War. Michael, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MANN: Thank you, Steve. Always a pleasure.

Related links:

- Watch “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix

- Read Michael Mann’s commentary: “Don’t Look Up. But Do See This Film!”

- High Country News | “How do you make a movie about a hyperobject?”

[MUSIC: Nicholas Britell “The End?” on Don’t Look Up (Soundtrack from the Netflix Film), Netflix Studios]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Jenni Doering, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Teresa Shi, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Destination Wildlife. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation, for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth