September 4, 2009

Air Date: September 4, 2009

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Where There’s Fire, There’s Smoke

/ Ingrid LobetView the page for this story

The smoke from California wildfires can have serious health consequences even for people who don’t consider themselves at risk. Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet spoke with two medical experts and has our report. (05:00)

The Man in the Middle

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

Pennsylvania Senator Arlen Specter switched parties; now, he's rethinking his position on climate change. Specter tells host Jeff Young he's open to a more aggressive approach to cutting greenhouse gases. We'll visit the Keystone State to find out where this key political player stands on global warming. (07:00)

Low Dose Makes the Poison

View the page for this story

Modern toxicology doesn't typically test chemicals for what they do at low doses. But, sometimes, small amounts of substances can be harmful to human health, especially when it comes to the hormone-mimicking chemicals known as endocrine disruptors. Pete Myers, chief scientist of Environmental Health Sciences, talks with host Jeff Young about what tiny exposures of common chemicals do in our body, and why regulatory agencies don't test low doses (07:00)

EPA’s Chemical Delay

View the page for this story

The Environmental Protection Agency has been slow to begin screening chemicals that could disturb the body's hormonal system. Thirteen years have passed without the agency testing a single chemical for the mandated Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program, and some worry that common exposures to substances like bisphenol-A could be bad for public health. Former EPA scientist Tracey Woodruff talks with host Steve Curwood about what the EPA is and isn't doing to protect the public from harmful chemicals. (06:00)

Smoke Gets Under Your Skin

/ Ike SriskandarajaView the page for this story

Everyone knows that smoking is bad for your health. But new research shows that it may be worse for smokers with dark skin. Dr. Gary King at the Penn State University has discovered a binding between nicotine and melanin. Living on Earth’s Ike Sriskandarajah reports. (04:55)

Heart Of Dryness

View the page for this story

The government of Botswana has stopped all water deliveries to the Kalahari Desert in an effort to drive indigenous Bushmen off their land. In the book “Heart of Dryness,” author James Workman recounts how the Bushmen conserve, share and trade water to persevere against an arid landscape. As he tells host Steve Curwood, lessons from the Bushmen can help us survive future water shortages. (07:45)

Robins and West Nile Virus

/ Laurie SandersView the page for this story

In the last ten years, the West Nile Virus has become the most commonly contracted, mosquito-transmitted virus in the Western Hemisphere. Scientists are trying to figure out how and why the infection has spread so quickly. In Connecticut, researchers discovered that the American Robin is the primary host. Producer Laurie Sanders went out with a group of scientists who are counting robins and trapping mosquitoes to find out more about West Nile. (05:50)

Meet your Meat

/ Lisa SongView the page for this story

Chestnut Farm in Hardwick, Massachusetts raises free-range animals and sells shares to members in exchange for a weekly supply of meat. Living on Earth’s Lisa Song took the farmers up on their offer to give participants a chance to tour the farm and “meet the meat.” (03:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Hosts: Steve Curwood and Jeff Young

Guests: J. Peterson Myers, Tracey Woodruff

Reporters: Ingrid Lobet, Laurie Sanders, Ike Sriskandarajah, Jeff Young

Sound Portrait: Lisa Song

[THEME]

YOUNG: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

YOUNG: I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

California burning – the damage from LA’s wildfires goes beyond the firelines to the lungs of millions exposed to the smoke.

MOROCCO: The percentage of the population that is really at risk is probably much greater than we talk about in the mass media. In fact, if you want to be really realistic about it, you probably should include everyone who breathes.

YOUNG: Also – a visit with Pennsylvania Senator Arlen Specter. He switched parties – now he’s rethinking his position on climate change.

CURWOOD: And – tracking the spread of West Nile virus up in the treetops

FOLSOM-OKEEFE: What we’re doing here tonight is we’re counting robins as they come into a roost. We’re in a suburban backyard in Hamden, Connecticut. And we’re actually interested in the role of roosts in West Nile Virus transmission.

YOUNG: Those stories and more - this week on Living on Earth! So stick around.

Where There’s Fire, There’s Smoke

(Photo: Michal Czerwonka, Courtesy of the EPA)

YOUNG: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The biggest blaze in the modern history of Los Angeles County may well yet set another record--the most Americans exposed at one time to the pollution generated by wildfire.

The “Station Fire” raging in the hills above Acton, California. (Photo: Michal Czerwonka, Courtesy of the EPA)

So, what does the addition of all that smoke into already smoggy LA mean for public health?

From Los Angeles Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet reports that it’s not just those people with respiratory problems who are at risk.

LOBET: Westerners are used to fire, and getting more used to it. But this most recent inferno, right on LA's north flank, impressed even the battle worn.

AVOL: This really has been a terrible catastrophe and it's SO widespread and the volume, the mass, the size of this… is just unbelievable.

LOBET: Dr. Ed Avol is a 40-year resident of the city. He's also an air pollution expert who teaches at USC medical school. Dr. Avol says smoke is filled with tiny particles. It's an especially intense form of air pollution.

AVOL: Well, the levels have been pretty extraordinary. In some of the inland valleys and across the whole city you can see the smoke pervade everywhere. The levels are in some places 10 or even 20 times above the standards, so they really are quite dramatically high.

LOBET: Dr. Avol says many people mistakenly believe that it's those with asthma who suffer most from the fires.

AVOL: Asthmatics tend to sort of be more aware of their body, more aware of their response to their surroundings and tend to take personal protective behavior. And so where the asthmatic child might say 'I don't feel right, I'm not going to exercise as much today,' their healthy peer may run around and over expose themselves.

And in fact we've done studies that reported that it's that group of non-asthmatics that have larger effects than the asthmatic children, and that of course, covers a much larger group.

MOROCCO: The percentage of the population that is really at risk is probably much greater than we talk about in the mass media.

LOBET: Mark Morocco is a supervising emergency room doctor and an associate professor at UCLA medical school. He also says people underestimate exactly who is affected by smoke.

MOROCCO: In fact, if you want to be really realistic about it, you probably should include everybody who breathes, even those folks who are healthy and essentially have no respiratory or cardio-pulmonary problems or would put themselves in a category like that are probably at some risk.

Smoke rises above La Canada Flintridge, California. (Photo: Michal Czerwonka, Courtesy of the EPA)

MOROCCO: So once you are exposed to smoke, we know that you are at increase risk for any kind of infections and so we could se a real uptick in our flu season, we could see an increasing number bacteria pneumonias, especially in elderly and immuno-compromised folks, folks who have other health problems.

LOBET: These acute affects, Dr. Morocco says are well known. Both experts agree what's unknown …are the long term affects. Again, Dr. Ed Avol.

AVOL: The big question we don't all know yet is whether repeated short insults like this lead to some permanent deleterious event, you know, where the tipping is.

LOBET: Can two weeks of fire every year for your first seven years cause asthma?

AVOL: Right, that's the question that we don't know yet. I mean clearly these insults-- because when the levels of pollution are so high, that you‘re getting dramatically increased exposure. Whether this leads to some lifelong problem while your lungs are growing, while your systems are developing, really is an issue and is something we should be thinking about.

(Photo: Michal Czerwonka, Courtesy of the EPA)

MOROCCO: If it turns out that the models that are postulated are true, and we go into having sort of 12-month fire season, we are going to spend our time essentially in an experiment where we are exposed to particulate matter continuously, where you’ll essentially be immersed in a soup for a long time, and then there is no telling what that will do in terms of long term health care and public health. But in terms of short-term public health, I think we are bound to see many people with more acute and more threatening pulmonary illnesses all around the calendar.

LOBET: Dr. Morocco says physicians will treat these patients as best they can one by one, but fire and smoke raise larger questions such as: how many of us live near the tinder dry woods, and even which cars we drive, far beyond the fire lands.

For Living on Earth, I'm Ingrid Lobet in Los Angeles.

The Man in the Middle

(Photo:Doug Webster, Netroots Nation 09)

YOUNG: California’s wildfires are one more reminder of the looming impacts of climate change. And they come just as Congress is about to return to work on climate change legislation.

In June the House passed a cap and trade bill. Now all eyes are on the Senate, especially a group of about twenty Senators—mostly Democrats--who could be the decisive votes. Among them is Pennsylvania Senator Arlen Specter, who recently switched parties to run for reelection as a Democrat.

It’s been a long hot summer for Senator Specter.

TOWN HALL MEETING: One day God’s gonna stand before you, and he’s gonna judge you and the rest of your damn cronies up on the hill!

YOUNG: Specter’s health care town halls got so rowdy headline writers dubbed them “town brawls.”

SPECTER AT TOWN HALL: Now wait a minute, now wait a minute.

YOUNG: Specter could soon feel some heat on global warming, too. He’ll play a key role as a new member of the committee drafting the Senate’s version of a bill to

limit the amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted, while setting up a system to trade emissions permits—known as cap and trade.

SPECTER: I believe we need legislation on global warming, on climate change. And I joined the environment and public works committee specifically so I’d

have a seat at the table because I consider it such an important issue.

YOUNG: I caught up with Sen. Specter in the midst of his hectic home state tour: conservative hecklers on one day, a convention of liberal bloggers the next. In front

of a mostly Democratic crowd in Pittsburgh, Specter talked up his record on climate change.

SPECTER (TO AUDIENCE AT CONVENTION): I think the global warming issue is long past due. In the last Congress, I supported the Bingaman and Specter bill, which was cap and trade. And, I support what President Obama wants to do.

YOUNG: But Specter left out a few details. He has not voted for any major climate bill in the Senate. The bill he sponsored with Democratic Senator Jeff Bingaman did not cut emissions as much as scientists say is needed.

Nor did Specter mention the letter he signed last month, along with nine other democrats, setting conditions for support of a climate bill. That letter calls for so-called

carbon tariffs, or penalties on imports from countries like China if they do not join an international climate agreement. The president opposes that, calling it

protectionism.

I asked Sen. Specter how he reconciles that record with support for the Obama agenda on climate change.

Sen. Specter takes questions at Netroots Nation, a convention of liberal bloggers in Pittsburgh. The previous day, he’d faced conservative hecklers at a town hall meeting. (Photo: Doug Webster for Netroots Nation 09)

SPECTER: Well it is the job of a senator to offer suggestions to what the president proposes. And then to try to work it out. You get legislation through accommodation by trying to work through it. Our goals I think are identical and how we get there is a subject for discussion.

YOUNG: Is that element of trade some sort of carbon tariff or a barrier say on Chinese steel, for example, is that a potential deal breaker for you on a vote for a climate change bill?

SPECTER: Well, at this point, I would not begin to talk about any deal breakers. I would say that we have to treat US industry fairly. When it comes to imports. I have argued 13 cases in the international trade commission. but let’s try to work it out.

YOUNG: Has your switch to the Democratic Party changed your position on energy or climate change at all?

SPECTER: No I had the same position as a Republican. I co-sponsored the Bingaman-Specter bill which was cap and trade.

YOUNG: Right, but one that a lot of the environmental community views as too weak in terms of its emissions reductions.

SPECTER: Well, the objective of legislation is to get it passed. I’m not in concrete on the standards we need to do something, which is technologically sustainable. Warner-Lieberman, which had tougher standards, proposed items, which we didn’t have the technology for. And also to get a bill passed you’ve got to have broad support.

But this is incremental, this is step by step and I’m prepared to negotiate and discuss tougher standards bearing in mind the total picture of jobs maintaining and

getting sufficient support to get it passed. We don’t want a super bill if you can’t get it passed.

YOUNG: If it sounds like Senator Specter’s trying to straddle a fence on those questions, well, consider the political terrain he’s trying to cover in Pennsylvania. It’s a

major coal mining state. And despite declines in steel and heavy industry, there are still 800 thousand workers in a manufacturing sector that’s sensitive to both foreign

competition and energy prices. But political scientist Terry Madonna, at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, says the state’s economy is starting

to green a bit.

MADONNA: The environmental community in Pennsylvania has shifted its focus to job creation and arguing that the energy or environmental changes they have proposed will produce new jobs, good paying jobs and I think that it’s an argument that has gained some momentum.

YOUNG: So Senator Specter’s got a real balancing act here, supporting those traditional energy intensive industries and this emerging green economy. And now he’s trying to do that as a Democrat?

MADONNA: you know, Senator Specter if nothing else is like Houdini through his political career, a master escape artist. I think that the senator will be hard pressed not to vote for a final version of the climate bill. But he is in the middle politically and what he does on the climate bill in particular in the senate is going to be very much observed and I think will be one of the two or three very important factors in

his primary battle with the left leaning congressman Joe Sestak.

The challenger: Specter’s Democratic opponent, Rep. Joe Sestak, cosponsored the House’s climate change bill. (Photo: Steve Stearns)

warming bill that emerged from the House, written by Representatives Henry Waxman and Ed Markey.

SESTAK: I had it as one of my campaign issues. So it was one of the five pillars that I ran on. And that’s why I immediately co-sponsored when it first went to Congress the

Waxman bill on climate change.

YOUNG: In contrast, Specter says he has not studied the Waxman-Markey bill enough to know if he supports it. A spokesperson says comments coming into the Senator’s office show Pennsylvanians have a high level of interest in the climate bill and they’re about evenly split for and against.

And Specters still hearing plenty from Pennsylvanians upset that he switched parties. Nevertheless Specter says his political life is easier as a Democrat.

SPECTER: I like it. And I don’t have to look over my right shoulder anymore. So, it’s comfortable again.

YOUNG: But not too comfortable. Now, as he mulls over his vote on climate change, Senator Specter might be looking over his left shoulder, instead.

CURWOOD: Coming up – the dose makes the poison – except sometimes, it doesn’t. Chemicals and hormones just ahead. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

Related links:

- The League of Conservation Voters’ scorecards for the environmental voting records of Sen. Specter…

- …and the scorecards for Rep. Sestak.

- Read the Environmental Defense Fund analysis of the Bingaman-Specter bill and other climate bills offered last year.

- Click here to see a graph of emissions reductions of Bingaman-Specter compared to other bills offered last year.

- Learn more about the trade implications of a “carbon tariff” in this Living on Earth interview with George Washington University law school Professor Steve Charnovitz.

[MUSIC: Roy Ayers “Liquid Love from Virgin Ubiquity 2 (Rapster 2005)]

Low Dose Makes the Poison

The endocrine disrupting chemical bisphenol-A, or BPA, lines many food and beverage containers, from baby bottles to canned veggies.

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

YOUNG: And I’m Jeff Young.

When toxicologists test a chemical’s safety they typically use high doses to find health problems. But that approach has missed the potential dangers of some substances that can be hazardous in tiny amounts. They’re known as endocrine disruptors because they mimic or block hormones. Some, like bisphenol A, and phthalates, are common ingredients in plastics and other consumer items.

Recently, the Government’s National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences published a paper challenging regulators to change chemical safety tests to reflect this emerging scientific understanding about low doses. Dr. J. Peterson Myers is the lead author.

MYERS: Our regulatory safety net, the FDA or the EPA, the all depend upon a core assumption – that when they test at high doses those tests will reveal what’s happening at low doses. The problem is that when you’re dealing with contaminants that behave like hormones, it doesn’t work that way.

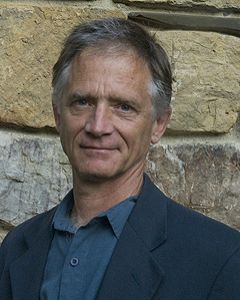

Pete Myers (Courtesy of Environment Health Sciences)

YOUNG: Why is it that these chemicals can start to show problems at low doses instead of at high doses?

MYERS: What hormones and these contaminants do is at very low doses they turn on and off genes. Genes are being turned on and off trillions of times a second throughout your lifetime. And the orchestration of that is absolutely vital to life. If the genes get turned on or off at the wrong time, that’s gonna lead to a problem. You’re gonna lack a protein that might be important for example in suppressing a tumor or in controlling the growth of your heart. And the body’s control system for these genes is designed to function at really, really low levels.

YOUNG: How low are we talking about?

MYERS: We’re talking parts per trillion to parts per billion to low parts per million.

YOUNG: And this is not even in the area where the safety system is designed to look.

MYERS: The safety system is not designed to look there. It starts at parts per thousand and rarely gets to low parts per million and never gets to parts per billion.

YOUNG: So we’ve all heard the phrase “the dose is the poison.” And that really is the assumption that a lot of toxicology is working on.

MYERS: It’s an assumption that’s been around since the 16th century. It was based upon work by a guy named Paracelsus in Switzerland. And the way the tests work today is we think that by testing at high doses we’re gonna see everything. So that once we get to a dose that’s intermediate and we don’t see anything, we’re golden.

But the science is telling us that at really low doses as contaminants mimic hormones. They can have effects that are totally unpredictable by what happens at high doses. And now we’re watching as toxicology is overturned by new science from endocrinology. Endocrinology is the study of hormones and its only because endocrinologists brought their skills and knowledge into this field and began asking these new questions that we began seeing the results like this beginning about a dozen years ago.

YOUNG: So it’s emerging science, but it’s not brand spanking new. Why haven’t we been looking for this sort of response when we’re trying to determine whether or not a substance is safe?

MYERS: I should emphasize that it’s not even close to brand spanking new. It’s solid in endocrinology. This is something that physicians have to structure their drug deliveries around. They know that at low doses you can cause effects that don’t happen at high doses. In fact, you can cause the opposite effect.

And the best example of that is a compound called Tamoxifen that’s used by physicians to cure breast cancer. It works at high doses to suppress the growth of the breast cancer tumor. That’s exactly what you want it to do. But at a level about a million fold beneath that toxic dose, it turns on genes that are responsive to estrogens and causes to breast tumor to grow. And if you only to the classic experiments of high doses until you don’t find and effect, you miss this.

YOUNG: And are we beginning to see that that’s happening, that the findings from endocrinology are indeed being put to work in our safety system?

MYERS: Well, not yet. There’s a battle underway today over bispenol A. The low dose experiments say it’s risky and we shouldn’t be using it with food products. But to date the agency reviews of bisphenol A have basically depended upon traditional high dose experiments by contract laboratories, and have not been willing to pay attention to the low dose studies published by academic scientists doing this new research.

Another endocrine disrupting compound that has been shown to have these different effects at low doses than at high doses are some of the phthalates, a common plasticizer added to plastic to make it pliable and soft. This fascinating work showing that at really low doses phthalates alter our responsiveness to allergens. They make us hyper allergic. So the standard tests that are used to assess toxicity don’t even begin to tell you about this effect of phthalates.

Phalates are a group of chemicals used to make plastics pliable. (Courtesy of Breast Cancer Fund)

YOUNG: So maybe that gives us some insight into why the bisphenol A issue is so hard fought. It’s about more than just BPA.

MYERS: It is about more than just BPA. BPA itself is a big deal. You do the calculation and it’s worth about $800,000 an hour. You can buy a lot of lawyers to defend your product with $800,000 an hour in revenue. But BPA is the poster child of this low dose debate. And if BPA is regulated based on low dose effects, it explicitly acknowledges that the regulatory system has been blind to these types of effects. And BPA is not the only one that’s gonna have to be re-examined.

YOUNG: Now EPA has been taking some steps in this direction. Give me an assessment of what the environmental protection agency’s been doing in terms of these endocrine disrupting chemicals?

MYERS: Very little. There’s a program that’s been underway mandated by the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 that instructed the EPA to develop testing and screening criteria for endocrine disrupting compounds. And just this past year, it identified candidates to measure. Congress actually expected them to be measuring these things within a few years and here we are 13 years after the passage of that act and EPA has just identified what candidates they should look at. And it’s a small incomplete list.

YOUNG: That's Dr. Pete Myers, CEO and chief scientist of the non-profit Environmental Health Sciences – that paper on endocrine disrupting chemicals is at our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Click here to read Pete Myers’ paper on the importance of low-dose testing.

- For more on Pete Myers and Environmental Health Sciences, click here.

- Click here to learn more about the EPA’s Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program.

- Click here for Living on Earth’s previous coverage of endocrine disruptors.

EPA’s Chemical Delay

CURWOOD: By the way, another chemical that’s risky at low doses is the herbicide atrazine, now banned in the European Union, but widely used here in the US. The Natural Resources Defense Council recently found troubling amounts of atrazine in three quarters of the streams in farming regions. To date the EPA has failed to act on atrazine, as well as the low-dose screening program, and the agency declined to talk with us for this week's show. So we called Dr. Tracey Woodruff, who worked as an EPA scientist for 13 years.

She now directs the program on reproductive health and the environment at the University of California at San Francisco.

WOODRUFF: I think EPA needs to do more to look at the question of endocrine disrupting chemicals. Clearly the effort they’ve made to date on implementing endocrine disruptors screening program could move a little faster. There has not been a whole lot of visible movement in that program since it was passed in 1996. So that was during the Clinton administration.

Tracey Woodruff (Courtesy of the University of California, San Francisco)

CURWOOD: Why do you think it’s been so slow to move?

WOODRUFF: Well I think – I think there’s many different things that come into play on why things can be slow particularly at a regulatory agency. One issue is gonna be the science and how do we vet through the science.

Certainly another important issue is who are the people who are concerned about this and what are the issues that they care about and how much influence to they have on the process moves. And clearly the testing of endocrine disrupting chemicals is a focal point for groups – both environmental groups, but also the regulated community who’s going to be concerned about how their chemicals are labeled.

CURWOOD: Some people remark that industry has really been trying to block or halt this process. How fair a criticism is that?

WOODRUFF: Industry clearly cares about what’s gonna happen with this program. Industry clearly has been talking to EPA about what they want to see. And EPA is more or less responsive to that depending on their own political considerations. So, one of the things that’s difficult about some of these programs that are set up something like this but don’t have enforceable deadlines is that things can drag out for a long time because EPA can spend a lot of time talking to lots of people and not necessarily moving forward. And if it’s not a high priority for the agency to move it forward, then it will get stuck.

CURWOOD: So, I know you’re in academia these days, but let’s say the phone rings and it’s President Obama. And he calls you up and he says “well how should the EPA now deal with endocrine disruptors?” What would you tell him?

WOODRUFF: [laughs] If President Obama called me on the phone that would be very exciting. My first priority would be to change the requirements so that we had to require information about chemicals that were gonna remain on the market so we knew whether they were gonna be a problem or not for public health.

CURWOOD: So test everything?

WOODRUFF: Well, I think everything should have some type of basic information set to know whether they’re a potential health problem.

CURWOOD: And how important would it be to move something like atrazine to the head of the queue?

WOODRUFF: Well I think atrazine actually has a lot of data looking at the exposures to atrazine and what the increased risks might be. So I’m not sure they need to put that through the endocrine disruptor screening program. I think EPA could take the data and science they have at hand and move right to the decision making process.

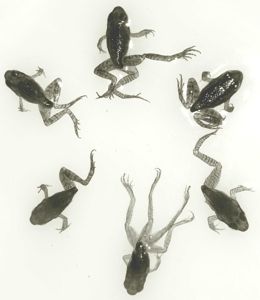

Scientists have found that levels of atrazine low enough to be considered safe for drinking by the EPA have caused deformities in frogs, including missing limbs, limb duplications, and sex changes. (Photo: Joseph Kiesecker, Penn State)

WOODRUFF: Yes, you have that right. Chemicals that have been on the market since the passage of the Toxic Substance Control Act do not require any testing unless EPA provides as large amount of data to prove that we should test something, which, of course, is very difficult to do. New chemicals that come onto the market do have to have a little bit of testing, but its not the complete set of testing that we would want to know for every chemical. And this seems a little bit odd that we have chemicals that are on the market which we have no idea whether they – at the levels that people are exposed – are safe of not.

CURWOOD: What substances that we’re exposed to regularly in low levels are you most concerned about?

WOODRUFF: It’s a little bit difficult to sort through because as you probably know, if you think about high production chemicals alone which is produced or imported in more than a million pounds – there’s almost 3,000. Some of the chemicals I’m concerned about are things that I think we haven’t been paying very much attention to. I mean, a lot of people are familiar with the bisphenol A and phthalates. I’m also very concerned about ones that are what we would consider emerging or that we haven’t been looking at very much.

CURWOOD: For example?

WOODRUFF: Triclosan, though to disrupt thyroid hormones, the cyclohexanes, which are a family of chemicals which are ubiquitous in consumer products and have been talked about in California as a substitute in dry cleaning for perchloroethylene. There’s some suspicion that it can disrupt uterine function. And then the nonylphenols, octylphenols which are found ubiquitously in the water supply and also thought to be an endocrine disrupting chemical.

CURWOOD: Well wait a second triclosan is in the deodorant soap that gets used in my household.

WOODRUFF: Yup.

CURWOOD: Nonylphenols are in detergents. So I should quit washing I guess.

WOODRUFF: [laughs] No you should not quit washing. But you can use products to wash your hands and wash your clothes that do not have necessarily all these chemicals. It’s very interesting about the soap and the triclosan and it’s in all these sort of antibacterial soaps, but there’s not a lot of evidence that we need to have quite the focus on these antibacterial soaps that we’re led to believe. I think if you can just wash your hands with some very plain soap, that works just as well.

CURWOOD: Tracey Woodruff is a former EPA scientist and she’s an associate professor at the University of California at San Francisco. Thank you so much, Dr. Woodruff.

WOODRUFF: Thank you.

[MUSIC: DJ Cam “Waiting For Franck Black” from Loa Project II (Six Degrees 2009)]

Related links:

- For more on Tracey Woodruff and her work, click here.

- The EPA’s Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program

- Tracey Woodruff recommends consumers check the GoodGuide for help in avoiding chemical exposure.

Smoke Gets Under Your Skin

Smoking is bad for you no matter what your color of skin, but dependence may increase with darkness. (Photo: Mendhak )

CURWOOD: Forty-five years ago the US Surgeon General reported that smoking is bad for your health. The message has sunk in: over 40 percent of Americans smoked then but now only about 20 percent do.

But new research says just how addictive smoking is for you depends on the color of your skin. Living on Earth’s Ike Sriskandarajah reports.

SRISKANDARAJAH: What would you say if I told you that the darker your skin is, the worse smoking is for you and the harder it is for you to quit?

VOX POP: Okay, so the more pigment I have in my skin, the worse smoking is for me- I’d say…

Is that scientific? You’re going to have to give me that information or back it up because to me that doesn’t make sense.

SRISKANDARAJAH: NO - the link’s not obvious - but Dr. Gary King from Pennsylvania State University is happy to explain his research.

Dr. King is a medical sociologist and a professor in the Departments of Biobehavioral Health and Sociology at the Pennsylvania State University.

KING: Hi, glad to be here.

SRISKANDARAJAH: He studies nicotine, which is the highly addictive stimulant that makes people crave cigarettes. And melanin, a compound your body makes that determines how dark you are. And he found a connection.

KING: In simple terms what we have discovered is that there is a binding between nicotine and melanin.

SRISKANDARAJAH: That means the melanin is strongly attracted to nicotine.

The way it works is when you light up a cigarette.

[SOUND OF LIGHTING A CIGARETTE]

SRISKANDARAJAH: And take a drag.

[SOUND OF INHALING]

SRISKANDARAJAH: The tobacco and all the chemicals created when it burns go in your mouth, into your lungs and the rest of your organs including your biggest organ … skin

KING: Skin does react to like every other organ in the body unto nicotine and the other 4,000 chemicals that are consumed when one actually smokes.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Inhaling thousands of chemicals is not a good idea. But it is especially bad for people with dark, melanin-rich skin. That’s because melanin grabs and hangs onto the nicotine.

KING: And that binding process in and of itself may lead to greater dependence.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Greater dependence means it’s much harder for darker skinned people to kick the habit. In fact white smokers on average are 15 percent better at quitting than blacks. Even though whites typically smoke about five more cigarettes a day.

KING: Nicotine doesn’t remain in the body for an extended period of time, which is one reason why smokers continually have to replenish their supply. The suggestion is that it does remain in their body much longer for African Americans than white Americans. African Americans typically smoke fewer cigarettes than Caucasian Americans and some other groups but yet still the dependence rate is much higher.

SRISKANDARAJAH: But that doesn’t mean white people are off the nicotine hook. Their lighter skin still makes the type of melanin we all accumulate from being in the sun.

KING: Absolutely, if in fact we are talking about sun exposed melanin or sun exposed parts of the body. Then this very well could affect populations that are more likely to perhaps to work in outdoor environments where there’s sun and, interestingly enough, may have implications for persons who live closer to the equator.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Which is why Dr. King’s next step is to survey dark and light skinned people all over the world. His findings are based on a pretty small sample- 150 subjects, all of whom are African American. The study targeted African Americans for several reasons- for one black people have the widest range of melanin concentration. Also, by focusing on African American communities, Dr. King says he was better able to control for the non-biological factors that influence smoking habits.

KING: Yes. Clearly we could not just look at two different variables and that is nicotine exposure and melanin but we had an array of other sociological factors such as one’s education, the amount of stress that a person was experiencing. We also looked at- we had a scale to measure racial discrimination. However, after controlling for all of these other factors including age and gender we did not find that they reduce the significance of our association between melanin and nicotine.

SRISKANDARAJAH: So, just to review; cigarettes are bad for you but turns out - the darker your skin, the harder it is to kick the habit. So if you absolutely have to smoke, at least do so in the shade.

KING: [laughs] Well, uhh, some might want to come to that conclusion. What we’ve done is something that we think is pretty groundbreaking and we certainly would like to explore much more fully but at the moment I could not comment- at least not authoritatively on that particular point.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Dr. Gary King is a professor in the Departments of Biobehavioral Health and Sociology at the Pennsylvania State University. For Living on Earth I’m Ike Sriskandarajah.

Supernatural Disaster “Unfortunately Mildred The Cows Smoke Too Many Cigarettes” from Season Of The Bird (Supernatural Disaster 2007)

YOUNG: Just ahead – water, water – nowhere. How some of the oldest tribes on earth might just be able to help us out. Stay with us - on Living on Earth.

Related link:

Click here to read the study on melanin and nicotine.

Heart Of Dryness

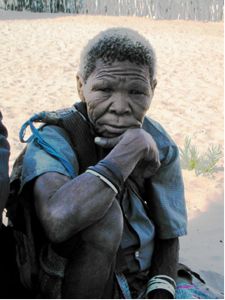

A woman at a sipwell. Sipwells are small bodies of water trapped underground. They’re difficult to detect, and knowledge of their secret locations is highly prized. (Photo: James Workman)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The Bushmen of the Kalahari in Africa have lived for tens of thousands of years – finding water, and scratching out an existence in the harsh desert landscape.

WORKMAN: It’s very drab, it’s very monotonous, it’s the closest I can imagine to a moonscape.

CURWOOD: That’s James Workman, an international water specialist from California who traveled in the Kalahari.

His new book is called “Heart of Dryness, How the last Bushmen can help us endure the coming age of permanent drought.” Mr. Workman says we should pay heed to the Bushmen because inevitable climate change will lead to growing global desertification, including dry areas like America’s southwest.

Bushmen gathering before a hunt. (Photo: James Workman)

WORKMAN: They moved them out to these reserves in Rakops and it wasn’t that there was less water, it was a monopoly of water. It was the government saying here’s a pipe and you get all the water you want. On the surface like ah, who can complain about that.

But it changed their life because there was nothing for them to organize their existence around. Before they’d been hunting and gathering and trading and exchanging and doing so on their own terms and time table. And then you hook ‘em up to a tap and that was it.

In some cases that water wasn’t as good a quality. When you concentrate people and animals around water you create all kinds of unintended negative effects of sewage in the water supply, of malaria because you’ve got standing water.

Qoroxloo, heroine of “Heart of Dryness.” (Photo: James Workman)

WORKMAN: They fell back on the old ways as they call them. So the elders became in many ways leaders of saying “okay. Here’s how we’re gonna cope. We know the secret places where water is hidden. We know when to capture it. We know how to use it.”

When I first approached them, I thought I was coming to rescue the Bushmen, and it turned out quite the opposite. Especially after my vehicle broke down in the middle of the Kalahari where I realized I have nothing to offer these guys. They’ve been here, they know what to do. On the other hand, if I can ever get out of here, which eventually I did with some help, I’m gonna see what they can do to help us.

CURWOOD: The Bushmen can survive in surprisingly arid conditions. What lifestyle choices make that possible and what might we learn from them as a society?

WORKMAN: You can’t increase supply. So what you have to do is somehow find ways to reduce demand. And they’re masters at that. They sequester water, they scoop it off. As soon as there’s a rainfall into a pan or into a tree and then they store it in a jug, a canister, an oil drum, ostrich shells, to prevent evaporation, whereas we do the exact opposite.

Digging for tubers and roots. The Bushmen can eat about 100 different plants from the Kalahari Desert. (Photo: James Workman)

CURWOOD: In your view, what’s the craziest thing that people here in the affluent west do with water?

WORKMAN: We grow rice in the desert. We store water in these five foot deep reservoirs. And the hardest things for us on a personal level to recognize is the idiocy of flush toilets. That uses not just a lot of water that could otherwise be used and saved for the environment, it pollutes it, it spreads disease and it requires a huge amount of energy. Here in California a fifth of the energy in the state goes towards treating and lifting and moving and warming water.

CURWOOD: Now somebody listening to us would say “okay, fine. You want us to live like the Bushmen of the Kalahari.” How do you deal with this in a modern, urban society?

WORKMAN: Well what we can do is adopt their approach to water and give it the kind of value that they do. There are incentives and there’s technology already available. Germany and Norway it’s almost become a fad to have what they call Ecosan – these, you know, composting toilets, which then turn our human waste into and asset. There are ways to minimize the impact that we leave and that’s the lesson from the Bushmen.

CURWOOD: It would be helpful if you could describe the Bushmen’s practices of trading water and ownership.

WORKMAN: The main thing is there’s no monopoly on water. I sort of came there thinking “oh, the Bushmen are primitive Marxists” because that was sort of the romantic idea I had. And it’s quite the opposite. They recognize the strength of each other, or who can gather, who can hunt, who had rights to the sip well, to that pan, to this, you know, foraging ground. They know and keep track of mentally who owes whom what. And that matters in times of scarcity because it relieves the pressure of saying “okay, you’re not pulling your weight” or “you’re wasting something.”

Squeezing water from a tuber. About 80% of the Bushmen's water comes from the food that they eat. (Photo: James Workman)

We don’t. The water in our toilet, in our sink, in our shower, in our gardens, we rent that, we borrow it, it’s subsidized in the same way it’s subsidized to farmers. And if you have something that you’re renting, you just don’t take as good care of it and you have no incentive to make it last, you have no incentive to trade it with your neighbors.

CURWOOD: So, how feasible is it to apply the Bushmen’s survival skills to developed countries?

WORKMAN: Well we have technology that they don’t. And our greatest technology in the last few years developed is the web, of course. What you have with Ebay, what you have with Amazon is this ability to trade with strangers and build trust.

And that’s the kind of thing I think we can adopt and which I’m trying to pioneer where you and somebody across the city from you – you’re all in the same water supply – you use, you know, fifty gallons, he uses 500 gallons. And if everybody gets the same amount of water, you can sell what you don’t use or you can save it to that stranger. It’s like an Ebay for the environment.

CURWOOD: One aspect of the case of the Bushmen that came up was a question of whether water is a basic human right.

WORKMAN: Yeah.

CURWOOD: Now, it seems to me that it’s impossible to live without water. So, what is the argument to say that water is not a human right?

WORKMAN: I’m siding with you exactly on that, but the counter point is like “wait – if water is a human right, then if some government fails to provide it through incompetence, do they get hauled up in front of the Hag?

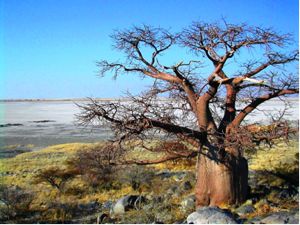

A baobab tree in the Kalahari Desert. (Photo: James Workman)

My answer is that it is a human right, but it need not be called that. You can quantify a certain amount for every single person, rich or poor, and if they use that amount, then it’s free. If they use less than that amount, which they own, then they can sell or save credits that they’ve earned. Water is an economic good and it’s a human right. And it’s both together and we can use it as such.

CURWOOD: James Workman’s new book is called “Heart of Dryness, How the last Bushmen can help us endure the coming age of permanent drought”. Thank you so much Jamie.

WORKMAN: Steve, thanks very much.

Related links:

- Heart of Dryness website

- Click here to watch a YouTube video about the Bushmen (filmed by an Australian team).

- Learn more about Survival International, a group that helped fund the Bushmen's court case against the Botswana government.

- Read a message from the First People of the Kalahari.

- For another Living on Earth story on the Bushmen, click here.

[MUSIC: Zaman 8 & Hafez Modir “Sani” from Six Degrees Of The Middle East (Six Degrees records 2009)]

Robins and West Nile Virus

(Photo: Laurie Sanders)

YOUNG: Ten years after it arrived in North America, West Nile Virus is in decline. The Centers for Disease Control says the number of reported cases in the US is down sharply.

But people aren’t the real target for West Nile. Producer Laurie Sanders visited with a team of scientists learning more about the virus by studying its primary hosts: birds.

SANDERS: When West Nile Virus appeared in New York City in 1999, it showed up first in birds, particularly crows. For the first few years, infected crows were dying by the thousands. At the time, the assumption was that crows were playing a major role in the virus’s cycling and transmission. But in 2005, a Connecticut-based study revealed that crows were not the main carrier. Instead, it was the familiar and beloved American Robin.

FOLSOM-OKEEFE: What we’re doing here tonight is we’re counting robins as they come into a roost. We’re in a suburban backyard in Hamden, CT. The robins like to roost in these trees.

SANDERS: Corrie Folsom-Okeefe is a research assistant at Yale University’s School of Public Health.

FOLSOM-OKEEFE: And they started roosting maybe about two weeks ago and they’ll continue to roost probably into September and we’re interested in the role of roosts in West Nile Virus transmission.

[CLUCKING IN ROOST]

SANDERS: These robins will spend the night together here, and come daybreak, they’ll fly away. In the case of many of the adult males, that means back to their nest site to help their mate with the business of raising a second brood. When the day’s over, they’ll come back again to this roost. Folsom-O’Keefe says at its peak, this site will have about 2,000 robins, but other roosts have more.

During the next few months, she and her team be visiting 6 roosts in the New Haven area, counting robins and trapping mosquitoes. In the process, they’re hoping to answer several questions. For instance, in the roost, in such close quarters, can robins actually infect each other with West Nile Virus? Is the virus infection rate higher in mosquitoes trapped near roosts? Does the mosquito infection rate vary between roosts? And, what is it about robins that mosquitoes find so appealing—are they actually secreting some special odor?

[LAB SOUNDS]

SANDERS: It’s here at the Connecticut Agricultural Station in New Haven that researchers are working with Yale to try to help answer these questions. The station is responsible for the state’s mosquito surveillance program, and each summer, at dozens of stations around the state, they trap about 200,000 mosquitoes. All those mosquitoes are sorted to species and tested for viruses.

Mike Thomas is one of the mosquito experts in the lab. He says back in 2005, it was this lab that had gathered the evidence that showed that crows played a small role in the spread of West Nile Virus and robins a much bigger one. And the evidence was right in the bellies of the mosquitoes.

Dr. Goudarz Molaei analyzes mosquito blood in the lab. (Photo: Courtesy of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station)

SANDERS: Capping the tube, Thomas puts the vial with the mosquito on ice. Thousands of vials are in this freezer.

[SOUND OF OPENING THE FREEZER DOOR]

MOLAEI: This is a scientific refrigerator that has the capability to go below -80 Celsius.

SANDERS: Goudarz Molaei, a molecular biologist, is responsible for analyzing the blood.

MOLAEI: …and prevents DNA degradation. We have in this freezer several 1000s of mosquitoes, blood engorged mosquitoes, collected from many regions in the US.

[RATTLING OF EQUIPMENT]

SANDERS: To do the analysis, Molaei clips off the blood filled belly from the rest of the mosquito’s body.

[WHIRRING OF CENTRIFUGE]

SANDERS: The abdomen is then placed in another vial, and using a series of techniques that were developed here—--Molaei is able to isolate the DNA in the blood, replicate it, and then by comparing the DNA sequence with an NIH database, he can figure out exactly what kind of animal the mosquito fed on. And it turns out mosquitoes are choosy. Some species feed only on reptiles and amphibians, others just on mammals, and some just on birds.

(Photo: Laurie Sanders)

MOLAEI: And 38% is a great percentage because when we analyze the mosquito blood meal we delt with over 30 species that mosquitos fed upon.

SANDERS: Molaei says based on that number, it’s probably also true that migrating robins played a key role in the rapid spread of West Nile Virus across North America and into Mexico and Central America. In just ten years, West Nile has become the most commonly contracted, mosquito-transmitted virus in the western hemisphere. However, there is some good news.

During the last two years, the number of human cases in the US has decreased sharply. As of late August, the Centers for Disease Control had reported only 123 confirmed human cases and four fatalities in 22 states. Less than a third as many as last year. Just why the decline has occurred is uncertain, but scientists speculate that through exposure, birds and humans may be developing a natural immunity. For Living on Earth, I’m Laurie Sanders.

Related links:

- Connecticut Mosquito Management Program

- CDC West Nile Virus Homepage

Meet your Meat

Cows grazing in the field at Chestnut Farms. (Photo: Lisa Song)

CURWOOD: Community Supported Agriculture has become hugely popular in many urban areas. Farmers sell shares, and the dividend is a weekly supply of fresh veg.

The charm of CSA’s as they are called is not just the fresh local food. Many also give their shareholders the chance to visit the farm, and see where their zucchini and onions and collards grow.

One CSA in Massachusetts offers a rare treat – the chance to “meet your meat”. That’s right, Chestnut Farms, in Hardwick – the state’s first meat CSA – holds regular Open Barn events.

Living on Earth’s Lisa Song went along - and brings us this sound portrait.

[BARN SOUNDS]

DENNEY: I’m Kim. And that’s my husband Rich. And we own and operate Chestnut Farms. And we raise all our animals in a humane and sustainable way.

[BARN SOUNDS]

DENNEY: We’re about much more than just putting a hamburger on your table.

A baby goat in the farm’s petting zoo during the Open Barn event.

[PIG GRUNTS]

DENNEY: We don’t name the ones that we eat. When we were first starting we would do cows for ourselves and our three children were younger and we would call the cows Dindin One, Dindin Two, Dindin Three. So that it was really clear that it was gonna be dindin. And I find that the kids are very sanguine about it. The kids are fine if they know you’re raising and animal to eat. It’s the moms – which I can relate – have a little stress.

[PIG GRUNTS]

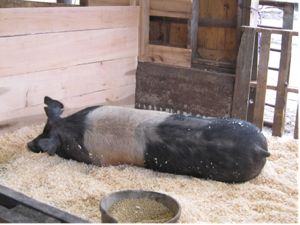

DENNEY: So you can see her and she’s a little full right now. See what a nice bum she’s got and that’s the hams and that’s what you look for as well as a long back. Which is more pork chops, more pork chops. You’re a good girl!

A pregnant pig in a “spa pen,” days before giving birth. (Photo: Lisa Song)

SONG: Can you tell me your name?

SAM: Sam.

SONG: And what do you do on the farm?

SAM: Raise the chickens. We have two kinds of eggs. We have Araucana eggs which are blue and Rhode Island Reds and Comet’s eggs are red.

[CHICKEN’S CLUCKING]

SAM: And the difference between them are Araucana eggs they’re supposed to be more healthy and stronger, that’s the blue eggs. And the other kind is just the regular eggs.

[CHICKEN’S CLUCKING]

WISE: My name is Marlisa Wise, and I’m the daughter of the owners and founders of Chestnut Farms.

[ANIMAL SOUNDS]

WISE: All of our animals are naturally raised, hormone free, grass feed. I mean we’re standing looking next to the fields right now and you can see that all of those calves that are out with their mothers right now, if they were on a conventional farm would have been pulled away only days after having been born.

And here we let them nurse until they wean naturally around, you know, six, eight months. A lot of people sort of don’t want to look at animal that they are going to eat as a steak or a hamburger later.

The chickens’ nesting boxes are kept in an old school bus, which is locked at night to protect against coyotes. (Photo credit: Brian Kardon)

[COWS MOOING, ROOSTERS CROWING]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Lisa Song created that audio postcard of the inhabitants of Chestnut Farm in Hardwick Massachusetts. For pictures, go to our website, loe.org

Louis Jordan “Barnyard Boogie” from The Best Of Louis Jordan (UMG Records 1975)

Related link:

Chestnut Farms website

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Bruce Gellerman, Ingrid Lobet, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, and Mitra Taj, with help from Sarah Calkins, Marilyn Govoni, and Sammy Souza.

YOUNG: Today we bid a sad farewell to our stellar interns Annie Glausser and Lisa Song – we expect great things of you both and we wish you the best of luck. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can find us anytime at loe.org.

I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth