Heart Of Dryness

Air Date: Week of September 4, 2009

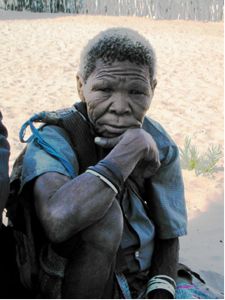

A woman at a sipwell. Sipwells are small bodies of water trapped underground. They’re difficult to detect, and knowledge of their secret locations is highly prized. (Photo: James Workman)

The government of Botswana has stopped all water deliveries to the Kalahari Desert in an effort to drive indigenous Bushmen off their land. In the book “Heart of Dryness,” author James Workman recounts how the Bushmen conserve, share and trade water to persevere against an arid landscape. As he tells host Steve Curwood, lessons from the Bushmen can help us survive future water shortages.

Transcript

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The Bushmen of the Kalahari in Africa have lived for tens of thousands of years – finding water, and scratching out an existence in the harsh desert landscape.

WORKMAN: It’s very drab, it’s very monotonous, it’s the closest I can imagine to a moonscape.

CURWOOD: That’s James Workman, an international water specialist from California who traveled in the Kalahari.

His new book is called “Heart of Dryness, How the last Bushmen can help us endure the coming age of permanent drought.” Mr. Workman says we should pay heed to the Bushmen because inevitable climate change will lead to growing global desertification, including dry areas like America’s southwest.

Bushmen gathering before a hunt. (Photo: James Workman)

WORKMAN: They moved them out to these reserves in Rakops and it wasn’t that there was less water, it was a monopoly of water. It was the government saying here’s a pipe and you get all the water you want. On the surface like ah, who can complain about that.

But it changed their life because there was nothing for them to organize their existence around. Before they’d been hunting and gathering and trading and exchanging and doing so on their own terms and time table. And then you hook ‘em up to a tap and that was it.

In some cases that water wasn’t as good a quality. When you concentrate people and animals around water you create all kinds of unintended negative effects of sewage in the water supply, of malaria because you’ve got standing water.

Qoroxloo, heroine of “Heart of Dryness.” (Photo: James Workman)

WORKMAN: They fell back on the old ways as they call them. So the elders became in many ways leaders of saying “okay. Here’s how we’re gonna cope. We know the secret places where water is hidden. We know when to capture it. We know how to use it.”

When I first approached them, I thought I was coming to rescue the Bushmen, and it turned out quite the opposite. Especially after my vehicle broke down in the middle of the Kalahari where I realized I have nothing to offer these guys. They’ve been here, they know what to do. On the other hand, if I can ever get out of here, which eventually I did with some help, I’m gonna see what they can do to help us.

CURWOOD: The Bushmen can survive in surprisingly arid conditions. What lifestyle choices make that possible and what might we learn from them as a society?

WORKMAN: You can’t increase supply. So what you have to do is somehow find ways to reduce demand. And they’re masters at that. They sequester water, they scoop it off. As soon as there’s a rainfall into a pan or into a tree and then they store it in a jug, a canister, an oil drum, ostrich shells, to prevent evaporation, whereas we do the exact opposite.

Digging for tubers and roots. The Bushmen can eat about 100 different plants from the Kalahari Desert. (Photo: James Workman)

CURWOOD: In your view, what’s the craziest thing that people here in the affluent west do with water?

WORKMAN: We grow rice in the desert. We store water in these five foot deep reservoirs. And the hardest things for us on a personal level to recognize is the idiocy of flush toilets. That uses not just a lot of water that could otherwise be used and saved for the environment, it pollutes it, it spreads disease and it requires a huge amount of energy. Here in California a fifth of the energy in the state goes towards treating and lifting and moving and warming water.

CURWOOD: Now somebody listening to us would say “okay, fine. You want us to live like the Bushmen of the Kalahari.” How do you deal with this in a modern, urban society?

WORKMAN: Well what we can do is adopt their approach to water and give it the kind of value that they do. There are incentives and there’s technology already available. Germany and Norway it’s almost become a fad to have what they call Ecosan – these, you know, composting toilets, which then turn our human waste into and asset. There are ways to minimize the impact that we leave and that’s the lesson from the Bushmen.

CURWOOD: It would be helpful if you could describe the Bushmen’s practices of trading water and ownership.

WORKMAN: The main thing is there’s no monopoly on water. I sort of came there thinking “oh, the Bushmen are primitive Marxists” because that was sort of the romantic idea I had. And it’s quite the opposite. They recognize the strength of each other, or who can gather, who can hunt, who had rights to the sip well, to that pan, to this, you know, foraging ground. They know and keep track of mentally who owes whom what. And that matters in times of scarcity because it relieves the pressure of saying “okay, you’re not pulling your weight” or “you’re wasting something.”

Squeezing water from a tuber. About 80% of the Bushmen's water comes from the food that they eat. (Photo: James Workman)

We don’t. The water in our toilet, in our sink, in our shower, in our gardens, we rent that, we borrow it, it’s subsidized in the same way it’s subsidized to farmers. And if you have something that you’re renting, you just don’t take as good care of it and you have no incentive to make it last, you have no incentive to trade it with your neighbors.

CURWOOD: So, how feasible is it to apply the Bushmen’s survival skills to developed countries?

WORKMAN: Well we have technology that they don’t. And our greatest technology in the last few years developed is the web, of course. What you have with Ebay, what you have with Amazon is this ability to trade with strangers and build trust.

And that’s the kind of thing I think we can adopt and which I’m trying to pioneer where you and somebody across the city from you – you’re all in the same water supply – you use, you know, fifty gallons, he uses 500 gallons. And if everybody gets the same amount of water, you can sell what you don’t use or you can save it to that stranger. It’s like an Ebay for the environment.

CURWOOD: One aspect of the case of the Bushmen that came up was a question of whether water is a basic human right.

WORKMAN: Yeah.

CURWOOD: Now, it seems to me that it’s impossible to live without water. So, what is the argument to say that water is not a human right?

WORKMAN: I’m siding with you exactly on that, but the counter point is like “wait – if water is a human right, then if some government fails to provide it through incompetence, do they get hauled up in front of the Hag?

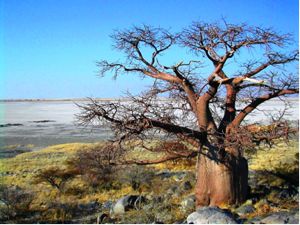

A baobab tree in the Kalahari Desert. (Photo: James Workman)

My answer is that it is a human right, but it need not be called that. You can quantify a certain amount for every single person, rich or poor, and if they use that amount, then it’s free. If they use less than that amount, which they own, then they can sell or save credits that they’ve earned. Water is an economic good and it’s a human right. And it’s both together and we can use it as such.

CURWOOD: James Workman’s new book is called “Heart of Dryness, How the last Bushmen can help us endure the coming age of permanent drought”. Thank you so much Jamie.

WORKMAN: Steve, thanks very much.

Links

Click here to watch a YouTube video about the Bushmen (filmed by an Australian team).

Read a message from the First People of the Kalahari.

For another Living on Earth story on the Bushmen, click here.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth