August 9, 2002

Air Date: August 9, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Watching for Fire

/ Jeff RiceView the page for this story

Once there were five thousand of them. But due to technology, the number of fire lookouts has dwindled to just a few hundred. Jeff Rice reports on what drives the people who belong to this vanishing breed to keep vigil over the forests of the West. (11:20)

Health Note/Teen Eating

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on a new study that found teen vegetarians may be eating healthier than their carnivorous counterparts. (01:30)

Almanac/Deep Sea Hot Springs

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about an underwater oasis, discovered twenty-five years ago, that re-defined the origins of life. (01:30)

Maggot P.I.

View the page for this story

A stray hair or a partial fingerprint could be the essential clues that seal a murder case. But a movement is afoot to incorporate maggots and flies in the routine investigation of crime. Host Steve Curwood talks with author Jessica Snyder-Sachs about her new book, Corpse: Nature, Forensics, and the Struggle to Pinpoint Time of Death. (08:00)

Coral Spawning

/ John RyanView the page for this story

John Ryan sent us a reporter's notebook entry after watching coral have sex in the reefs off the coast of Indonesia. (04:20)

Hand-me-down Feathers

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood talks with Christine Sheppard of the Bronx Zoo. She coordinates an innovative program that exports molted feathers from hornbills in U.S. zoos to Malaysia, where they can be used in traditional ceremonies. (03:00)

Tech Note/Travelpod

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports on a new system of public transportation – the travel pod. (01:20)

Alaska Wonderland

/ Guy HandView the page for this story

The Copper River Delta in Alaska is one of the last truly wild places in the country. Producer Guy Hand rafts down river, and tells a story of unexpected personal discovery. (14:30)

EarthEar

View the page for this story

The sounds of Alaska’s Columbia Glacier. ()

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodREPORTERS: Jeff Rice, John Ryan, Guy HandGUESTS: Jessica Snyder-Sachs, Christine SheppardNOTES: Diane Toomey, Cynthia Graber

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR News, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. In the southeast corner of Alaska there’s a place so wild and so majestic, it changes almost everyone who gets a chance to experience its glaciers and its grizzlies.

HICKEY: He was a big guy.

CURWOOD: The Copper River Delta can be a humbling place for humans, especially if you dare to take a raft down the rambling river. And if you dare – watch out for those giant falling icebergs.

[SOUND OF WATER]

LANKARD: In my lifetime I’ve seen two big faces fall, and it pushed these two women who were standing by the bank 250 feet back into the brush. And when they came to, one of them was in a tree and the other one kind of leaned over, looked to her right and here was a big, fat salmon flopping, trying to get back in the water. [Laughter.]

CURWOOD: It’s a Copper River caravan, this week on Living on Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

Watching for Fire

CURWOOD: Welcome to an encore addition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Wildfires have once again ravaged the West this summer. And so the work of the fire lookout has been gaining increasing importance. Once, more than 5,000 lookouts served as the primary means of fire detection for the U.S. Forest Service. Today, all but 300 of them are gone. Jeff Rice has our look at this vanishing part of American culture.

RICE: In 1910, what seemed like half of Idaho and Montana suddenly went up in flames. More than three million acres burned in just two days. Eighty-five firefighters died. And it still remains the worst fire in U.S. history. Soon after that, little box huts of wood and glass began to sprout on mountaintops across the country and people were hired for the summer, to live in them and watch over the forests. Ray Kresek is a fire lookout historian.

KRESEK: The experience required to become a lookout is virtually nil. Lowest paying job on the ladder. But, at one time, it was considered the most valuable job in the Forest Service. It was the eyes of the fire detection system.

RICE: You had your radio and your binoculars, your wood stove, and those who could stand the solitude had the chance to live, for a few quiet months, among the high peaks.

KRESEK: You were king of the mountain and you had a purpose that really had rewards other than money.

READER: In the morning I woke up and it was beautiful. Blue, sunshine sky, and I went out in my alpine yard and there it was: hundreds of miles of pure snow-covered rocks and virgin lakes and high timber.

RICE: In 1956, Jack Kerouac spent two months on a lookout in Washington state, spending the time drying out from alcohol and hard living.

READER: And below, instead of the world, I saw a sea of marshmallow clouds as flat as a roof and extending miles and miles in every direction, creaming all the valleys.

RICE: The experience turned the beat poet into a first-class nature writer, in his book "The Dharma Bums." Desolation Peak was barren and windy and his writing is a mixture of lonely despair and rapture. No alcohol, no pills, no grass, just the void and Mount Hozameen staring back at him.

READER: And it was all mine. Not another pair of eyes in the world was looking at this immense cycloramic universe of matter.

[WATER SOUNDS]

RICE: Gradually, lookouts across the country, including Kerouac’s, have been phased out, replaced by technology like satellites and spotter planes. Now only about 300 in the U.S. are still functioning. One of the few places where they’re still widely used is Idaho. Certain factors here still make lookouts a cost effective way of monitoring the forest. Part of it is tradition – the lookouts are already in place – and part of it has to do with the vast amounts of federal and state forestland. About 30 million acres of ponderosa pine and spruce spread from the tip of the panhandle to the edge of the low deserts. With so much area to cover, it’s too expensive to rely solely on spotter planes. It helps to have extra pairs of eyes, on the mountain. Lookouts are essentially weather spotters and what they watch for is lightning. Aside from the occasional careless campfire, lightning is the main event here. And over on Long Tom lookout, in the Salmon-Challis National Forest, Janet Bloemeke describes what it’s like to witness a storm blow in.

BLOEMEKE: You watch the cloud build, from blue sky to your first little puff, and watch the vertical development and an anvil, and you start seeing your first strikes, and you’re waiting to see, well, which direction is it going to move?

RICE: Then it occurs to you, she says. You have one of those lookout epiphanies. You’re at the highest point on a mountain, and Zeus is not happy.

BLOOMEKE: And we were just like, oh my god, it’s coming, and we’re not only going to be, like, in its path, we’re going to be in it.

[MUSIC: Wagner’s "Ride of the Valkyries" ]

BLOOMEKE: And it was like being in a room with, like, a bunch of strobe lights, just that flashy, blue, consistent light. And you could feel the electrical charge building up, because the hair on your arms will start to stand up and tingle. And I just thought, you know, it’s just a matter of time before this lookout just gets slammed.

[MUSIC CONTINUES]

BLOEMEKE: It was intense, it was really intense. And then, when they go off, when you’re in them like that and the adrenaline rush and stuff, and then when it starts dancing across the ridges and coming right at you, you just get really excited. When it hits, it’s so quick. I mean, there’s a sudden flash of white light. At the same time there’s like a crack of a whip and a loud boom and you know that you’ve been hit. And, like, within ten minutes you turn in seven fires. I don’t know. I guess it’s the lightning rush that I really live for, up here.

[MUSIC AND THUNDER]

RICE: If you ever got stuck on a mountaintop during a storm, you could stop by Howard Crist’s lookout, on the Boise National Forest. He’d be happy to take you in out of the rain, offer you some coffee, and maybe a little bourbon.

CRIST: You’re welcome to stay as long as you can. Let’s just be comfortable and talk.

RICE: Howard scans the view from 8,000 foot Jackson Peak. He’s a tall man in his fifties, with generous shocks of tousled gray hair, and he’s in constant motion, circulating the catwalk around the lookout, 15 feet off the ground, watching for phantom fires.

CRIST: I’ve always thought what I liked about it and kind of what got me addicted to it was the fact that you spend anywhere from 12 to 16 hours a day walking around, just letting thoughts run through your head. I mean, wasn’t it Nietzsche who said that the only thoughts that man ever came up with that were worth anything were done while he’s walking?

RICE: The job, understandably, attracts a more philosophical type of person, particularly those who don’t mind making 11 or 12 bucks an hour plus overtime. Crist says he’s held a lot of jobs, among them college professor, documentary filmmaker and cemetery plot salesman. And for the past nine years he’s worked in the summer as a fire lookout.

CRIST: It’s a good way to spend three or four months out of the year. It’s an addiction, it gets in your blood and it’s hard to get out.

RICE: Inside his one-room lookout, a square box that’s mostly windows, Crist prepares a meal of ramen noodles on a hot plate, patiently waiting for the water to boil at the high altitude.

CRIST: Water’s going to boil.

RICE: His faithful companion lounges on the bunk in the corner.

CRIST: That’s the cat, Spazz.

[SPAZZ MEOWS]

CRIST: Way to go, Spazz. I spent three days on a lookout without a cat, and that’s the only time I swore I’d ever do it. I’d never do it again. The chipmunks were carrying stuff out as fast as I carried it in, you know. So he keeps them at bay.

[SPAZZ MEOWS]

RICE: The job of a lookout might seem boring to some people: a full day of watching the horizon, roughly sun up to sun down, with a few breaks thrown in. But Crist doesn’t see it that way. He came up here thinking he could use the time to write, but became captivated by the job.

CRIST: My first thought was, yeah, you can come up here, you can get a book written. Well, truth of the matter is, while the sun’s up that landscape is changing and the moment, it’s hard to concentrate on something else. Because the moment you’re concentrating on something else, it’s like closing your eyes, you know what I mean? And you’re up here because of your eyes, really.

[CRIST TALKING TO DISPATCH]

CRIST: There’s a lot of people down there that don’t think lookouts have anything to do until there’s a fire come up. But, how do you find it? It’s like looking for a needle in the haystack. You keep telling yourself it’s there, you just haven’t found it yet.

[DISPATCHER SOUNDS]

RICE: When he does see a fire, he uses a device that hasn’t changed much since the ’30s. It’s a telescope that sits at the center of the room, like the navigational equipment on a seagoing ship. By knowing the location of two fixed points you can use it to figure out exactly where the fire is and call in its location. But actually spotting the fires in the first place is the real trick. In the same way that maybe a native Alaskan understands the subtleties of snow and ice, fire lookouts know fire. For instance, lightning fires don’t always burn hot. They tend to smolder. So for Crist, fires are like ghosts hiding in the underbrush.

A main feature inside the lookout is a "fire finder" which is used to triangulate the locations of fires. Photo: Guy Hand

CRIST: So it can stay there for a week, two weeks, and just kind of creep around. And it may come up once. But then when that brush burns and the fire continues on its way, if the fuels aren’t there to keep it real hot, it’s gone, it doesn’t seem to exist, because you can’t see it.

[DISPATCHER]

RICE: This type of fire behavior, its phantom-like creeping around on the forest floor, is one of the reasons some people still swear by lookouts. Fires like these are nearly impossible to catch from aerial spotter planes.

KRESEK: Air patrols that are put up by the Forest Service, sometimes every day, sometimes twice a day, they still only pass over any given area for an instant.

RICE: Lookout historian Ray Kresek.

KRESEK: And if a lightning strike is smoldering, the odds are great that it’s not going to be smoking enough to see when that plane goes over.

RICE: Kresek will go as far as to say that reopening more lookouts could save lives. Catching the fires early, before they become big conflagrations, like the blowup that killed four fire fighters this past summer in Washington State. At one time, there had been a manned lookout just a few miles away.

KRESEK: The fire would have been seen sooner had the lookout just two and a half miles away been in service. There’s no doubt in the world it would have been seen before it became five acres. It was five acres before it was reported.

RICE: In fact, some lookouts are being re-manned. Numbers fluctuate, but about 70 are still in operation in Idaho. Many are being preserved for their historical value and, in some cases, you can rent lookouts, as a vacation spot. It’s a rethinking of attitudes prevalent in past years, when many lookouts were seen as eyesores that were no longer useful. Some were even burned down, to clear away any signs that they had ever stood. Whatever the future holds, the opportunity to work a lookout still exists, and, as long as that’s the case, people like Howard Crist will keep coming back.

CRIST: I keep telling myself every year’s going to be the last, and there’ve been years that I haven’t been able to do it. And every time I see a lightning storm I start kicking myself and saying, why aren’t you on top of the mountain, where you belong?

RICE: For Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Rice, in Boise, Idaho.

Related links:

- National Historic Lookout Register

- Forest Fire Lookout Association

- Forest Fire Lookout Museum, Spokane WA

Health Note/Teen Eating

CURWOOD: Just ahead, creepy crawly crime solvers. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey:

[THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: While parents might be concerned about teenagers and their fickle eating habits, a new study shows that vegetarian adolescents may have the healthiest diets. Researchers at the University of Minnesota set out to answer the question: do teen vegetarians eat better than their meat eating counterparts? In what they describe as the first large-scale study of its kind, they asked more than 4,500 middle and high school students to fill out questionnaires about their diets. The researchers evaluated the answers based on dietary guidelines put out by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. They include the recommendation that people get less than 30 percent of their calories from fat, and they also promote a diet that includes at least three servings of vegetables a day.

Eighty percent of the vegetarians met the guidelines for fat consumption, but less than half of the meat-eating students did. And vegetarians were more than twice as likely to eat enough vegetables. Another group of students who described themselves as vegetarian but who did eat poultry and fish were also more likely than non-vegetarians to meet the guidelines. But when it came to calcium consumption, vegetarians and meat eaters alike scored the same low marks. Only about 30 percent of all students ate enough calcium-rich food. That’s this week’s Health Note. I’m Diane Toomey.

[THEME MUSIC OUT]

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living On Earth.

Related links:

- Abstract of the study on adolescent vegetarians published in Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine

- Editorial on adolescent vegetarians from Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine

Almanac/Deep Sea Hot Springs

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Trisome 21, "Magnified Section of Dreams", A MILLION LIGHTS (Play It Again Sam – 1987)]

CURWOOD: Twenty-five years ago a group of deep-sea researchers stumbled on life in an unexpected place. They took a submarine named Alvin on a dive 200 miles northeast of the Galapagos Islands and went so deep into the ocean all natural light disappeared. A mile and a half below the surface they turned the submarine’s lights on, and they saw what they expected – a virtual moonscape, devoid of life. At the time, you see, everyone thought photosynthesis was the source of energy for all organisms and where there was no light, there was no life. But as Alvin crept along, a small crab suddenly skittered across the sea floor. The astonished crew followed, the temperature started to rise, and the water turned cloudy. Giant white clams appeared, as well as three-foot long tubeworms and six-inch yellow mussels. It was a huge community, built around deep-sea hot springs, and the first ever ecosystem discovered to be independent of solar radiation. Instead of photosynthesis, chemosynthesis is the key to life in these hydrothermal areas, and bacteria break down sulfur compounds to serve as food for deep-sea critters. The discovery bent all previous rules for life and revealed a thriving underworld that was anything but green. And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

Maggot P.I.

CURWOOD: In those old TV detective shows you might see Columbo pull a notebook out of his wrinkled trench coat pocket as he hunches over a corpse. But you probably wouldn’t catch him using a butterfly net at a murder scene. Well that’s all changing, at least in the real world. One of the most difficult things to determine is the exact time of death. And increasingly investigators are finding that Mother Nature may well be the ultimate witness. Joining me now is Jessica Snyder-Sachs. She’s author of Corpse: Nature, Forensics and the Struggle to Pinpoint Time of Death. Welcome to Living on Earth.

SYNDER-SACHS: Hi, Steve.

CURWOOD: Perhaps you could introduce the subject of your book by talking about the case of the Devil’s Beef Tub, this case from England, and actually, at one point, you even called this case worthy of Scotland Yard lore. Please tell us the story.

SNYDER-SACHS: Right. This is a case, one of the first cases where police looked beyond their own forensic circles for help. And it starts on a late September morning in 1935, where a young woman is crossing a bridge near Moffat, Scotland. And she happens to look down. There had been a big rain a few days before so the river had been up and came down and had scattered a lot of parcels along the bank. And she looks closer and sees part of a human arm in one of them.

CURWOOD: Oh my.

SNYDER-SACHS: Right. So clearly, she runs and gets the police. They start searching this ravine, which came to be known ever after as the Devil’s Beef Tub, and they found 70 parcels, different pieces of human beings, which they pieced together. It looked like they had two people here, but all the identifying features had been gouged out. So it turns out a doctor’s wife, Isabella Ruxton, had gone missing with her family’s nursemaid. But Ruxton claims his wife and the nursemaid had actually gone to Scotland on holiday, on the 16th or 17th, and that he had an alibi after that. So this all very much hinges on when the women were killed.

So – and this is the part that’s worthy of Scotland lore – one of the pathologists at the University of Glasgow plucked some maggots off of one of the packages. Medical examiners, maggots are something they know, and they usually wash it off the autopsy table. But he took them down the hall, to an entomologist, a bug scientist, Alexander Mearns. And, sure enough, Mearns identified the larva, first as the larva of blue bottle fly. And he says, I can count back to when these eggs were laid. And then Mearns counts. It takes so many hours for the eggs to hatch, so many days for the larva to mature to the point where what he got was a nice, plump, third instar larva, kind of like a teenage maggot right before it’s ready to turn into a fly.

So he counts back and he says these were laid on the morning of September 16th, which blows Ruxton’s alibi and fits with the police’s scenario of him killing them and dumping their bodies that night. So the next morning, when the sun comes up, makes it nice and warm enough for flies to be about, the flies arrived, found the packages, and in fact Ruxton was convicted and executed, and after his death, it was published, his jail cell confession: he had killed his wife in a fit of rage and killed the nursemaid when she walked in and discovered them.

CURWOOD: Now, tell me, how sensitive are flies to death?

SNYDER-SACHS: The molecules that are given off at death waft into the air and up to a mile away blow flies and flesh flies can pick up those molecules and then they just follow the gradient, ever more concentrated molecules, to the scene of death. And they first start arriving – if the body is outdoors, it’s a sunny day – they’ll start arriving within minutes.

CURWOOD: What, now, do scientists do to pinpoint the time of death?

SNYDER-SACHS: Well, this has been bedeviling pathologists for centuries. They tried all sorts of high-tech tests to test muscle excitability and eye dilation and different chemicals, and they just don’t work outside the laboratory with actual murders, actual deaths. So where they’re finding success is really outside trying to medically diagnose death. But bringing in scientists, like entomologists, who are looking at the body kind of as a ecosystem, and looking at that wonderful way that nature reclaims the body, and quantifying how it does that so they can count back, to death.

CURWOOD: Now, we focused mainly on flies here, but what other parts of nature are now used in forensics?

SNYDER-SACHS: Good question. Often, it’s by combining different parts of nature, as you say, that they get their best time estimates, and so botanists will sometimes look for clues: a body might drop on a plant and shade it from the sun and sometimes they can estimate that way. Also, anthropologists are looking at the soil, or bedding, or whatever is beneath the corpse, and looking for products of bacterial decay. Chemists are trying to look at that and see if they can make sense out of the chaos, as in what rate do the bacteria break our muscles down into protein, amino acids and simpler chemicals.

CURWOOD: At what point in your research for this book did you first witness nature’s forensics in action?

SNYDER-SACHS: Well, initially, I was invited to some workshops that the entomologists give for state troopers, FBI agents, et cetera, where they used 50 pound pigs as human corpse stand-ins. And from there I was invited to assist Neil Haskell, a forensic entmologist, with his work at the so-called body farm at the University of Tennessee. And it’s in the back parking lot of the University of Tennessee Medical Center. You go all the way to the back of employee parking and you see a gray stockade fence, topped with barbed wire and a bio hazard sign. And after somebody opens a few padlocks you walk in, and the first thing you see, of course, are bodies – some of them just lying in the open, some of them stuffed in garbage bags, kind of protruding. There are abandoned cars, which they use sometimes, and anthropologists, entomologists, botanists are studying how the body decomposes and how they can calculate the time since death, based on their research there.

CURWOOD: This is a pretty grisly topic. What made you want to write about it in the first place and then to keep on writing?

SNYDER-SACHS: What I find beautiful is the whole ecology of how the body is taken back to nature, ashes to ashes, dust to dust. And I also like that here’s one case where nature is trumping technology. You walk into a forensic laboratory and they’re filled to the ceiling with all these high tech machines, to gas chromatographs, spectrometers, you know, machines for DNA analysis. But when it comes to determining time of death, they’re useless. So you bring these ecologists in, who look at the plants and the bugs and the microbes on the body, and they’re the ones who are giving us the answers that have been sought for hundreds of years.

CURWOOD: Jessica Snyder-Sachs is author of the book Corpse: Nature, Forensics, and the Struggle to Pinpoint the Time of Death. Thanks for joining us.

SNYDER-SACHS: Thank you, Steve.

Related link:

Corpse: Nature, Forensics, and the Struggle to Pinpoint Time of Death

Coral Spawning

CURWOOD: John Ryan is a journalist who travels the world looking for a good story and a good time. Recently, he found both on a small island just off the coast of Indonesia.

RYAN: I admit it, I went to Gililawa Lawt Island for the sex, but I promise, I only wanted to watch. Let me explain. Gililawa Laut is a harsh and uninhabited speck of land in Indonesia’s Komodo National Park. But just beyond its blistering shores are some of the world’s richest coral reefs, home to some of the most spectacular and bizarre sexual events in nature. The sex lives of corals were largely a mystery until a moonlit night in 1981 when scientists first observed a mass spawning of corals on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Corals are usually about as animated as rocks, but on that night they were spewing millions of eggs and sperm into the sea, turning the crystal clear waters into a sort of multi-color underwater snow storm. Australian scientists now know that on a few special nights a year, up to 40 coral species, most of them hermaphrodites, simultaneously blast pink, purple and green packets of spawn, in living blizzards of reproduction. The spawn form slicks on the surface so big and bright they’re visible from outer space. To see corals spawning, you have to be brave enough to swim in the ocean at night, and exceedingly lucky.

Photograph courtesy of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

Away from the Great Barrier Reef, scientists still know very little about the timing of coral spawning. But I dove above the reefs of Gililawa Lout to see another kind of sex spectacle. These reefs are known to scientists and fishermen as a spawning aggregation site: a place where fish gather to spawn in massive numbers, when the moon and tides are right. Above the colorful but motionless corals were dozens of groupers, some with neon blue polka-dots, others honeycombed with perfect hexagons from head to tail, shimmying alongside each other, fighting, and making sudden, mad dashes toward the surface to spawn. At one point, I wasn’t sure what I was seeing. Up ahead, a small group of very large parrot fish, as big as me, hovering like blimps, occasionally lurching forward to take large, noisy bites out of the reef. Behind them, I noticed a cloud in the water that didn’t look like the usual parrot fish poop, of freshly ground coral sand. Had the clumsy looking reef giants just spawned? I swam forward to find out. If I’m not mistaken, it was my first, and I hope last, time swimming through a cloud of sperm.

Most reef fish not only practice group sex, they actually change their gender. Groupers, wrasses and parrot fish all start out as females and a lucky, or unlucky few, depending on your point of view, become males. When a dominant male wrasse dies, the ranking female from his harem soon takes his place. During her metamorphosis her appearance can change so much that you’d have no reason to think he’s the same species, let alone the same individual, as she was before. I can’t even begin to fathom what human societies might be like if, say, we all changed our sex and skin color when we turned thirty.

Unfortunately for reef fish, there’s no such thing as a free orgy. Groupers’ sexual lifestyle choice of gathering in rather distracted groups, at specific times and places, leaves them extremely vulnerable to overfishing. Once a spawning aggregation site is discovered, it can be wiped out permanently, in just a year or two.

Here in Komodo National Park, as in most of Southeast Asia, grouper spawning sites have been hammered by the trade in live fish for seafood restaurants in Hong Kong and for aquariums in the west. The usual technique for catching reef fish alive is for divers to stun them with squirts of cyanide, then crack the reefs apart with crowbars to extract the fish from their hiding places. There’s big money in this dirty work. A single 90 pound Napoleon wrasse can sell for more than $5,000 in Hong Kong.

Indonesia has banned cyanide fishing and the export of endangered species, but the cash strapped and often corrupt authorities rarely enforce the law. In Komodo, the Nature Conservancy is funding park patrols against destructive fishing. But given the outrageous prices that live fish fetch in Hong Kong, it’s an uphill battle. In the end, the surest way to allow Indonesian fish to keep satisfying their unusual desires may be to get the gourmet consumers of Hong Kong to curb theirs.

CURWOOD: John Ryan is a Seattle-based journalist and author of Seven Wonders: Everyday Things for a Healthier Planet.

Hand-me-down Feathers

CURWOOD: You’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth. In Southeast Asia, the Rhinoceros Hornbill is often killed for its feathers used in traditional ceremonies. Scientists at the Wildlife Conservation Society came up with a novel solution to help halt the decline of this rare bird. Why not use the feathers that fall from captive birds in zoos? Christine Sheppard leads this effort from the Bronx Zoo. Dr. Sheppard, how did you come up with this idea?

SHEPPARD: Well, I’d known for a long time that the federal government has a repository of bald eagle and golden eagle feathers that are made available to Native Americans for ceremonial purposes. And someone I work with, Dr. Elizabeth Bennett, who’s been part of the Malaysia Wildlife Service for about 20 years, became very concerned – about five years ago, the increase in eco-tourism was causing an increase in native dance performances. And one of the popular dances was one that was done with Hornbill feathers. Each of the dancers has a fan of these feathers on each hand so that the hands represent wings. And the dance represents the birds in flight.

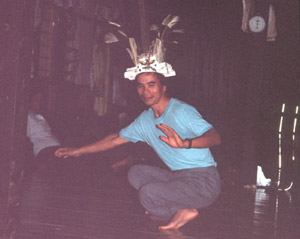

Malaysian dancer with Hornbill feather adornment. Photo: Elizabeth L. Bennett

They only use the central tail feathers. So it’s only a few feathers from any bird, which is why it makes much more sense to get a crop of feathers every year from a bird that is sort of done with them, than it does to shoot a bird, which can never produce another set of feathers.

CURWOOD: Can you describe these Hornbills for me? What do these feathers look like?

SHEPPARD: Well they’re basically black and white. They’re maybe, I don’t know, 18 inches long. They have a pretty squared off tail. And, if you think of the tail as being all white with a black band across the middle, that’s what they look like.

Photo: Wildlife Conservation Society.

CURWOOD: So, what was the response when you started calling around to various zoos that have Hornbills?

SHEPPARD: Every single zoo that has these Hornbills was extremely excited about becoming part of this program. Because we are always looking for ways that we can support conservation of our animals in the field.

Dr. Elizabeth Bennett (left) and Dr. Christine Sheppard with donated Hornbill feathers. Photo: Dennis DeMello, Wildlife Conservation Society

CURWOOD: I would think that part of the power of doing the dance, in an ancient society, would be from all the work that went into getting these feathers. How appropriate is it to use captive feathers for something like this?

SHEPPARD: Well that’s actually a very complicated question. The feathers that we’re providing are really for real ceremonies. Dr. Bennett came up with what I think is an absolutely brilliant idea of providing white turkey feathers which people could die a black band across for basically performances for tourists. And she did discuss with the headmen of various villages whether or not they would find it inappropriate to use tail feathers that were brought in from birds that had been in the United States. And they were delighted, partly because, in many of the areas that we’re talking about, the birds have basically disappeared because of hunting pressures. So they did not seem to have any difficulty whatsoever. It’s the bird itself that’s important, not where it is.

[SOUND OF HORNBILL CALL]

CURWOOD: Christine Sheppard is a curator for ornithology at the Bronx-based Wildlife Conservation Society. Thanks for taking this time with us today.

SHEPPARD: It was great to be here.

Related link:

Interested in adopting a Hornbill breeding nest?

Tech Note/Travelpod

CURWOOD: Coming up, a trip through Alaska’s Copper River Delta. First this Environmental Technology Note from Cynthia Graber.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

GRABER: It’s white, it’s light, and it’ll zip past traffic to get you to your destination. It’s your own travel pod, part of a new public transportation system called "Urban Light Transport," or ULTra. Cardiff, the capital of Wales, is the test site for the ULTra pods that will be posted at designated stops along the city streets. Commuters hop in and program their destination into a computer. The pod, which fits four passengers, glides along at about 25 miles per hour. A computer system keeps it from colliding with other ULTras along a network of tracks that take up only about half as much space as a car lane.

When you reach your desired stop, the pod door opens and out you go. Designers say the ULTra system should cost about half as much as a conventional light rail system, while providing reliable and regular service. And since they’ll run on batteries that recharge at every stop, the pods will reduce inner city pollution, along with congestion and the need for parking space. The first system should be running in Cardiff by 2004. Advanced Transport Systems Limited, the company developing the pods, is already in discussion with governments around the world about bringing ULTra travel pods to other cities, maybe one near you. That’s this week’s Technology Note. I’m Cynthia Graber.

[MUSIC UNDER]

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

Related link:

ULTra Advanced Transport System Ltd

Alaska Wonderland

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. There are few places left in the world as majestic as Alaska’s Copper River. This is a watershed bordered by massive glaciers. And the Copper River Delta that runs through them forms the largest undivided wetland on the west coast of North America. Each spring its skies grow dark as millions of shorebirds and waterfowl return. And so do millions of salmon. Producer Guy Hand went down the Copper River on a raft and found that facts and figures amount to only a fraction of this river’s story.

[SOUNDS OF RUSHING WATER]

HAND: As a journalist, especially an environmental journalist, I often write about loss, about lands that have been diminished or even destroyed. But this assignment should be different. The Copper River, although it’s threatened, is one of the most pristine waterways in the world. And I see another difference. My 12 raft-mates don’t look like the scientists, policy-makers and hardheaded pragmatists I’m used to.

[SOUND OF LAUGHING RAFT-MATES]

HAND: We’ve all been invited to the river by the Eyak Preservation Council, a conservation group based in Cordova. None of us know each other. It’s a kind of six-day blind date.

[SINGING AND TALKING]

HAND: David Grimes, an old hand at Copper River rafting, welcomes us to fast, frigid water.

GRIMES: By great miracle we have all survived in our lives long enough to be here together today for a life-changing adventure. As a friend of mine has said, at the end of the river trip you’re not the same person that you were at the beginning. So, think about what it is you might want to – how you might want to be different or what you might want to be like when you’re done at the other end.

HAND: David’s got the long hair, mischievous eyes, and mystical flourishes of a shaman. And I’m suddenly wondering if we’re headed into the terrain of natural history or some druidic form of self-improvement.

GRIMES: But this is one of the world’s great wild salmon rivers that still remains. As you know, down the coast a ways, they’re going extinct, and up here they’re still thriving. And that’s because there hasn’t been so many rascal humans around here so much. And one of the reasons we invite you all here to this home country is so that you will fall in love with the salmon and the bears and the water, and you will become more like salmon and bears, and so that we can take care of this precious place.

HAND: Reporters struggle to keep a certain emotional distance, not only from the people they interview, but from the places they report on. That’s why I often find it easier to work with botanists and biologists than poets and philosophers. Scientists describe nature through facts, figures, things a reporter can dive into without drowning.

[GROUPS LAUNCH RAFTS]

ALL: One, two, three!

HAND: We divide ourselves among three rubber rafts and lug them to the water. Once on the river, my worries fade a little, as the sheer power of this place begins to sink in. The current pulses past alder forest at a fast clip, and soon we’re lost in the kind of country that few people ever see or even imagine exists. It’s so remote, only a handful of mountains have names.

[SOUND OF PADDLING]

HAND: So what’s this mountain?

GRIMES: Spirit Mountain, which as we were saying, is the only named mountain for the next 80 miles on the river. It is a spiritual place. And spiritual in a very physical sense, too, because you’re different when you get out in places like this. You go onto river time, and pretty soon you don’t really remember when you weren’t on the river.

HAND: After a few hours, I begin to see that David, an accomplished songwriter and musician, may lean toward the mystical, but it’s grounded in real, hands-on experience. He’s floated the Copper for years. And soon I realize that no one can read its shifting currents better.

GRIMES: Let me spin the boat around here or we’re going to fetch up on the bar here.

HAND: I tilt my head back, staring up at Spirit Mountain some 7,000 feet high, and realize I spend way too much time with reading glasses grafted to my face, focusing on facts no further than a foot away, forgetting how big the world really is.

GRIMES: You know, in places the valley’s a couple miles across and you can see a long ways.

WOMAN: Yeah!

GRIMES: You get the knife okay?

HAND: At camp we catch a salmon.

WOMAN: It’s a beautiful one.

LANKARD: Every time we catch these beautiful fish, it’s an honor to just have them a part of our lives. You’re able to feed everybody that’s with you.

HAND: Dune Lankard, an Eyak native and another of our guides, grabs a knife to clean the fish. Dune has become one of the area’s most vocal proponents for keeping the Copper River watershed in its natural state.

LANKARD: My Eyak name is Jamachakih. And Jamachakih means "the little bird that screams really loud and won’t shut up." And I received that name shortly after the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

HAND: The Exxon Valdez ran aground just west of the Copper River Delta in 1989. It devastated the local fishing economy but created a community dedicated to protecting this place from future environmental tragedy. Salmon like the one Dune holds in his hands and begins to scale are one of the most obvious reasons he’s gone from fisherman to activist. Salmon are the fragile cornerstone of an ecosystem that feeds not only people, but bear, seal, eagle, otter, and many others. Salmon are reason enough, Dune believes, to fight development that threatens to chop this watershed into pieces.

LANKARD: Right now, you have just a whole bunch of development ideas from people that are sitting back deciding how they’re going to compartmentalize this whole region and not look at it as one whole ecosystem. Right now, the University of Alaska is trying to choose land up around Long Lake and they want 20 percent of the Copper River salmon-spawning habitat so they can clear cut it and build subdivisions. You’ve got the Chugash Corporation that wants to build a gold mine on the Bremner River. Then you have the governor, who of course wants to build this 65-mile trail so he can bring at least 100,000 to as many as a-million-and-a-half users annually down the river.

HAND: There’s also talk of oil drilling, remote resort lodges, and a deep water port that would draw large commercial vessels and cruise ships to the delta. Pro-development groups believe the Copper River communities need to expand their economic bases beyond fishing. They cite the Exxon Valdez incident as a perfect reason to diversify, to not shrink from development, but embrace it.

[GRIMES SINGING]

HAND: As we settle around the campfire and Dave sings one of his songs, I realize we haven’t seen a sign of other people all day long. The sky is a forest of stars.

[MUSIC FADES, SOUND OF RIVER COMES UP]

HAND: But as we break camp one morning, a sign that we’re sharing this place with other creatures is everywhere. Joe Hickey, from Lexington, Kentucky, woke up in the middle of the night.

HICKEY: I heard something. I didn’t know whether it was a bear or not. But it didn’t sound like a human. But I didn’t realize that he was this close to the tent.

HAND: In the sand, inches from Joe’s tent, are huge grizzly prints.

HICKEY: He was a big guy.

HAND: In spite of these close encounters, Nana Borchert is glad to be here.

BORCHERT: Having lived in Lapland for quite long, in Northern Sweden, where the nature’s also very beautiful but where all the rivers have been dammed, it’s so amazing to see that here salmon can still spawn and live, and whereas in Lapland none of the fish can spawn anymore because of the dammed rivers. And all the people have disappeared there too, that lived there, from fishing for subsistence. It just feels very good to know that people still can fish here and that the fish have their home here too.

[SOUND OF PADDLING]

HAND: Back on the Copper, maybe it’s our fourth or fifth day now. My earlier worries of suffering a week of eco-mysticism have faded away. I recorded lots of conversations about the science of this place. But even the most hard-nosed reporter would soften, surrounded by all this water, all this wilderness. We float past a sandstone cliff and throw a few echoes over the river.

[SOUND OF SHOUTING AND ECHOES]

HAND: Around noon we hit the beach.

MAN: The ground is just covered in bear tracks.

WOMAN: It’s like a beach party.

WOMAN: It’s incredible.

HAND: And soon we see more than tracks.

HOLLAWAY: You are too far right. Go left a little more.

HAND: Megan Hollaway tries to help Andy Woods zero in with binoculars on a couple of grizzlies as they fish for salmon on the far shore.

HOLLAWAY: So, go to the water, and then just at the edge of the water, where the current spins right there, there’s a mama and cubs.

WOODS: Oh, yeah!

HOLLAWAY: And you have to...

WOODS: I got him, I got him, I got him!

HAND: You see him?

WOODS: Yep. My first ever bear.

HOLLAWAY: Grizzly bears.

WOODS: Grizzly bears.

HAND: Dune smiles. Andy’s bear sighting is exactly the reason he brings people on these trips.

LANKARD: Because once they get here and they see this place, they’ll never go all the way back home. They’ll figure out how to help us save this place.

WOODS: I’m standing here naked with a pair of binoculars on, and I could die happy.

HAND: The Copper River watershed lies within the Chugash National Forest, the second largest in America. Ninety-eight percent of it is still unroaded, untouched. Yet few laws stand in the way of development. Not a single acre is protected as wilderness.

[PADDLING]

LANKARD: The glacier behind us is Miles Glacier, and all these icebergs that we’re going to be coming into here are pieces that break off.

HAND: Dune is paddling us toward a massive, frozen river that the Copper has cut into a four-hundred-foot cliff. Luminous shards of blue ice, some of them the size of office buildings, drift by. When the light hits them just right it breaks into rainbows. But we soon learn that just because this land is beautiful, it isn’t benign.

[GLACIER BOOMS]

HAND: Chunks of ice are calving off the glacier face in the warm August sun. So far, they’re small. But if a large piece falls, a tidal wave could form.

Have you guys ever been here when a big hunk calved off?

LANKARD: On this glacier, no. In my lifetime, I’ve seen two big faces fall.

HAND: One year, a 30-foot wave came off a glacier near here.

LANKARD: And it pushed these two women who were standing by the bank 250 feet back into the brush. And when they came to, one of them was in a tree, and the other one had big icebergs lying all around her, and she heard this flopping. And she kind of leaned over and looked to her right, and here was a big, fat salmon floppin’, trying to get back in the water.

[OOHS AND AAHS AS GLACIER BREAKS]

HAND: Small pieces are breaking up all over one section of the glacier.

[LOUD BOOM]

LANKARD: There it goes. Oh my God!

HAND: Suddenly, the whole face seems to break free. It falls in slow motion. And as it disappears, water explodes from the river, shooting hundreds of feet in the air.

LANKARD: Okay, that’s going to be a big wave.

GRIMES: We’re going to get a big wave.

LANKARD: Okay, get your paddles ready.

HAND: The horizon seems to lift up. Hundreds of displaced gulls launch into the air, and we grab for our paddles.

LANKARD: And if it’s pretty high – do you see a lot of ice moving? Then turn your heads this way so…

HAND: At this point, I turn my recorder off and stuff it into a bag I’ve tied to the raft. But then we see that the wave is rolling at an angle, the worst of it moving to our left. And all we get is a gentle rise and fall.

[SOUND OF SONG]

HAND: We set up camp just west of the glacier. Nana accompanies Dave on fiddle as we quietly eat soup around the fire, lost in a kind of near-miss euphoria. Leah Rachocki from Anchorage.

RACHOCKI: I thought today was unusually spectacular. I’ve never really had a day like today. Four hundred feet of ice fell into the water, and magnificent waves came, and we survived in a little rubber raft. (Laughs.) And now the stars are out and I saw a shooting star and it’s lovely.

HAND: In the distance, blades of ice are still falling into the river, and if that isn’t enough, the northern lights begin to lick across the sky in cool blue flames. It’s a kind of thunder and lightning I could never have imagined. It’s stunning.

Okay, it’s easy to slide over the top, trying to describe the sublime in nature. That’s why I mostly stick to the measurable. But on this last night on the Copper River, I can hear in the voices of those around me something else. E.O. Wilson calls it biophilia, a biological need, if not downright love, for the natural world. He says we humans are hard-wired for it. I’ll just call it wonder. And how do you measure that?

WOMAN: Wow. That was the nicest shooting star I think I’ve ever seen in my life.

HAND: For Living on Earth, I’m Guy Hand.

WOMAN: Wow. And it left a trail.

MAN: Are you seeing things again?

WOMAN: Yeah. It might have been the mushrooms I ate earlier. I wasn’t sure if they were hallucinogens or…

EarthEar

The sounds of Alaska’s Columbia Glacier.

Related link:

Jonathon Storm "Glacial Meltwater" RIVER OF ICE (EarthEar - 2000)

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s Living On Earth. Next week a Native American tribe mounts a campaign to save its language from extinction.

MAN: Why would you want to speak Blackfoot? They don’t speak it in Great Falls, they don’t speak it in New York, they don’t speak it at the universities. I think that’s really missing the point entirely. If it speaks well in my own soul, then that’s really what it’s about.

CURWOOD: The struggle to preserve endangered languages. Next week on Living On Earth.

[MUSIC]

[WATER/GLACIER SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: We leave you today with a tour of the inside of a glacier. Jonathan Storm recorded the sounds of falling melt water and ice crystals at the Columbia Glacier in Alaska. The Columbia Glacier calves both large and small icebergs into Prince William Sound.

[WATER/GLACIER SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Living On Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Maggie Villiger, Jennifer Chu, Ana Soloman-Greenbaum and Al Avery along with Julie O’Neill, Susan Shepard, Carly Ferguson and Jessica Penney. Special thanks to Ernie Silver.

We had help this week from Jamie McEvoy, Max Morange and Emma Uwodukunda. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Dennis Foley. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor and Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living On Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from The World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for coverage of Western issues, The National Science Foundation, supporting environmental education, and The Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth’s expanded internet service.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth